Strategies to Control Nanoparticle Aggregation: From Synthesis to Clinical Application

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of nanoparticle aggregation, a critical challenge that compromises efficacy in drug delivery and biomedical applications.

Strategies to Control Nanoparticle Aggregation: From Synthesis to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of nanoparticle aggregation, a critical challenge that compromises efficacy in drug delivery and biomedical applications. It explores the fundamental mechanisms driving aggregation, from synthesis to interaction with complex biological environments. The content details advanced methodological strategies for prevention, including surface engineering, green synthesis, and AI-driven optimization. Further, it covers practical troubleshooting and optimization protocols, alongside state-of-the-art validation techniques for characterizing and ensuring nanoparticle stability. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current knowledge to guide the development of stable, effective, and clinically translatable nanomedicines.

Understanding Nanoparticle Aggregation: Causes, Consequences, and Underlying Mechanisms

Fundamental Concepts: What is Nanoparticle Aggregation?

What is the formal definition of nanoparticle aggregation?

Nanoparticle aggregation is a process where individual nanoparticles (NPs) irreversibly attach to one another, typically through strong physical or chemical bonds at their interfaces, forming larger, often irregular clusters [1] [2]. This differs from flocculation, a reversible clustering often preceded by changes in pH or ionic strength where particles can be re-suspended [2]. Aggregation is distinct from controlled assembly, which is a directed process to create structured materials from nanoparticles [3].

What fundamental forces govern aggregation behavior?

The stability of nanoparticles in a suspension and their tendency to aggregate are governed by the balance of attractive and repulsive forces between particles, as described by classical Derjaguin, Landau, Verwey, and Overbeek (DLVO) theory and its extensions [3].

The following table summarizes the key interactive forces:

Table 1: Key Interparticle Forces Governing Nanoparticle Aggregation

| Force | Type | Origin | Role in Aggregation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Van der Waals | Attractive | Interactions of electrons and dipoles in particles [3]. | Primary attractive force driving particles together [1]. |

| Electrostatic | Repulsive (for like charges) | Surface charges and the surrounding electric double layer [3]. | Stabilizes particles by creating an energy barrier against aggregation [1] [3]. |

| Steric | Repulsive | Exclusion of solvent and compression of surface ligands or coatings [3]. | Prevents aggregation by creating a physical barrier between particle cores [3]. |

| Hydrophobic | Attractive | Decrease in solubility of the shell protecting the NP surface [3]. | Can drive aggregation in aqueous environments. |

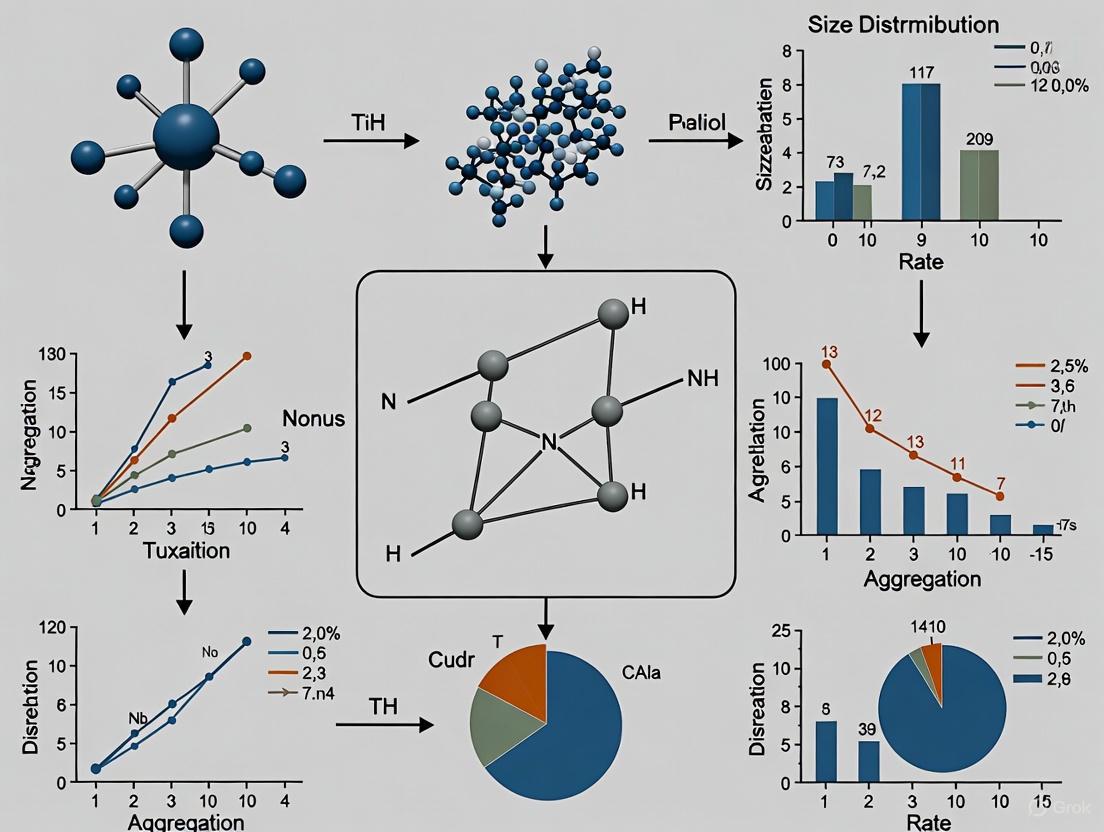

The following diagram illustrates the combined effect of these forces on interaction energy and the resultant nanoparticle states:

Troubleshooting Guide: Preventing and Managing Aggregation

How do I prevent nanoparticle aggregation during synthesis and processing?

Preventing aggregation requires controlling experimental conditions to favor repulsive forces. Key strategies include:

- Optimize Surface Chemistry: Use charge stabilization (e.g., citrate-coated gold nanospheres) or steric stabilization (e.g., PEGylation) to create a repulsive barrier [2] [3].

- Control Buffer Conditions: Maintain a pH that keeps the nanoparticle surface charge high, typically near neutral for many systems. Avoid high ionic strength buffers (like PBS) with charge-stabilized particles, as ions shield surface charges and promote aggregation [4] [2].

- Manage Physical Stresses: Avoid freezing, over-concentrating, or centrifuging nanoparticles beyond recommended speeds, as these processes can push particles into the primary minimum of the interaction energy diagram [2].

- Use Stabilizing Additives: Incorporate stabilizers like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or polyethylene glycol (PEG) after conjugation to prevent non-specific binding and improve stability [4].

What are the immediate steps to take if I observe aggregation?

If you notice visible precipitation or a change in the colloidal suspension's appearance:

- Diagnose the Cause: Check for recent changes in buffer, pH, or handling procedures [2].

- For Flocculation (reversible): Gently sonicate the sample or adjust the pH back to the recommended range to re-disperse the particles [2].

- For Aggregation (often irreversible): Attempt to recover non-aggregated particles by filtering the suspension through a 0.2 μm filter. However, this may not be feasible for all applications and signifies a need to re-optimize the protocol [2].

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol: Assessing Nanoparticle Stability via Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

This protocol is used to monitor nanoparticle size and detect early signs of aggregation.

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the nanoparticle sample to an appropriate concentration in the exact buffer of interest. Ensure the solution is free of dust or large contaminants by using a 0.2 μm filter [1].

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the DLS instrument using a standard of known size according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Measurement: Place the sample in a cuvette and measure the hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI) at a controlled temperature (e.g., 25°C). Perform at least three measurements per sample.

- Data Analysis: A stable, monodisperse sample will show a low PDI (e.g., <0.2). An increase in average hydrodynamic diameter and/or PDI over time indicates aggregation or instability [1].

Protocol: Functionalization of Gold Nanoparticles with PEG for Steric Stabilization

This protocol outlines a method to prevent aggregation in biologically relevant buffers.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for PEGylation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Citrate-stabilized AuNPs | Core nanoparticle material. | Particle concentration and initial size should be characterized. |

| Methoxy-PEG-Thiol | Forms a steric stabilization layer on the gold surface via strong Au-S bonds. | Prevents aggregation even in high ionic strength buffers. |

| Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4) | Reaction buffer. | Provides a stable, physiological pH for the reaction. |

| Dialysis Tubing or Filters | Purifies functionalized NPs from excess reagents. | Molecular weight cutoff must be appropriate to retain PEGylated NPs. |

Procedure:

- Activation: Add a solution of mPEG-Thiol to the citrate-stabilized gold nanoparticle suspension under gentle stirring. The typical molar ratio of PEG to nanoparticle surface area must be optimized for full coverage [2] [3].

- Reaction: Allow the reaction to proceed for several hours at room temperature.

- Purification: Remove unbound mPEG-Thiol by dialysis or centrifugal filtration against a mild buffer (e.g., 2-5 mM NaCl).

- Verification: Confirm successful PEGylation by measuring the hydrodynamic diameter increase via DLS and testing stability in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Stable PEGylated particles should not aggregate in PBS, whereas citrate-stabilized ones will [2].

The workflow for this stabilization protocol is summarized below:

FAQ: Addressing Common Scenarios in Research

My nanoparticles aggregate when I transfer them from water to a biological buffer. What is happening?

This is a classic issue of colloidal destabilization. Biological buffers like PBS have a high ionic strength. For nanoparticles stabilized by electrostatic repulsion (e.g., citrate-coated gold), the ions in the buffer shield the surface charges, collapsing the electric double layer. This reduces the repulsive energy barrier, allowing attractive van der Waals forces to dominate and cause aggregation [2]. Solution: Switch to steric stabilization by functionalizing nanoparticles with a polymer like PEG, which provides a physical barrier that remains effective in high-salt environments [2] [3].

How does the synthesis method influence aggregation later on?

The synthesis method dictates the nanoparticle's initial size, shape, and surface chemistry, which are critical for stability. For example, biological synthesis using bacteria or plant extracts often results in nanoparticles capped with biomolecules that act as natural stabilizers [5]. In contrast, nanoparticles synthesized in the gas phase or through some chemical methods may lack robust surface ligands, making them inherently prone to aggregation upon dispersion or drying [1].

Can I reverse nanoparticle aggregation once it has occurred?

It is very difficult to reverse true aggregation, as particles are held together in a deep primary minimum by strong forces [1] [2]. While gentle sonication or pH adjustment can sometimes reverse flocculation, aggregated particles typically require vigorous processing that can alter their properties. The most reliable strategy is prevention through careful control of the environment and surface chemistry from the outset [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do my nanoparticles aggregate when I add them to a standard phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution? This is a classic sign of charge shielding. Nanoparticles stabilized by electrostatic repulsion, such as those with citrate coatings, are sensitive to high ionic strength environments. PBS contains high salt concentrations, which compresses the electrical double layer around the particles, weakening the repulsive forces between them and allowing van der Waals attraction to cause aggregation [2]. For applications in biological buffers, consider switching to steric stabilization using polymers like polyethylene glycol (PEG) [2].

FAQ 2: How does the protein corona affect the targeting ability of my ligand-functionalized nanoparticles? The protein corona can physically mask the targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides) attached to the nanoparticle surface, preventing them from recognizing and binding to their intended receptors on cells. This "shielding" effect is a major hurdle for active targeting in biological systems [6]. Strategies to overcome this include designing surfaces that resist non-specific protein adsorption or using innovative platforms, like galloylated liposomes, that help maintain ligand orientation and functionality even after corona formation [6].

FAQ 3: I observe unpredictable aggregation during synthesis or gelation. What environmental factor could be causing this? Atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO₂) can be a surprising culprit. Research has shown that CO₂ can induce the aggregation of citrate-stabilized gold nanoparticles during silica aerogel synthesis, even when other parameters seem controlled [7]. Performing reactions under an inert atmosphere like argon or oxygen can mitigate this, though oxygen poses safety risks with flammable solvents. A more practical solution is to use polymeric stabilizers like poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) (PVP) that protect nanoparticles even in the presence of CO₂ [7].

FAQ 4: Can I predict whether a biomolecule will adsorb onto my nanoparticle's surface? Yes, electrostatic interactions are a primary predictor. A biomolecule (like a protein) will typically adsorb onto a nanoparticle surface with an opposite charge. The isoelectric point (pI) of the protein and the pH of the surrounding medium are critical. At a pH above its pI, a protein is negatively charged and will be attracted to positively charged nanoparticles. Conversely, at a pH below its pI, it is positively charged and will adsorb to negative surfaces [8]. Environmental factors like ionic strength and temperature also fine-tune this interaction [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Aggregation in Biological Buffers

Issue: Nanoparticles aggregate upon introduction to cell culture media or physiological buffers.

| Underlying Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Charge Shielding [2] | Measure zeta potential in low-ionic-strength water vs. buffer. A sharp drop indicates sensitivity. | Use steric stabilizers (e.g., PEG, PVP) instead of, or in addition to, charge stabilizers [2]. |

| Interactions with Serum Proteins [9] | Incubate with serum and measure increase in hydrodynamic size via DLS. | Pre-coat nanoparticles with inert proteins (e.g., albumin) or engineer a stealth surface to create a predictable corona [10]. |

Problem 2: Loss of Targeting Efficiency

Issue: Ligand-decorated nanoparticles perform well in vitro but lose targeting specificity in vivo or in serum-containing media.

| Underlying Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Corona Shielding [6] | Recover nanoparticles from serum, isolate the corona, and use SDS-PAGE or MS to identify adsorbed proteins. | Use pre-adsorption techniques that preserve ligand orientation. Galloylated liposomes have shown promise in keeping targeting ligands functional despite corona formation [6]. |

| Incorrect Ligand Density/Orientation | Use techniques like NMR or ELISA to confirm ligand accessibility after conjugation. | Optimize ligand conjugation chemistry and density. Use linkers that keep ligands extended from the surface. |

Problem 3: Inconsistent Biomolecule Loading

Issue: The amount of therapeutic biomolecule (e.g., DNA, drug, protein) loaded onto nanoparticles varies significantly between batches.

| Underlying Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled Electrostatic Adsorption | Measure zeta potential before and after loading. Small changes may indicate low loading efficiency. | Functionalize surfaces with high-density charged groups (e.g., -COOH, -NH₂) using methods like silanization [8]. Precisely control pH and ionic strength during loading [8]. |

| Competitive Binding from Protein Corona | Incubate NPs with the biomolecule in pure buffer vs. serum-containing medium and quantify loading. | Load the biomolecule in a controlled, protein-free environment before introducing the nanoparticles to complex biological fluids. |

Table 1: Influence of Environmental Factors on Electrostatic Adsorption and Aggregation

| Factor | Effect on Electrostatic Interactions | Experimental Impact |

|---|---|---|

| pH | Determines the ionization state of surface functional groups and biomolecules. At pH above the pI, surfaces/biomolecules are negative; below pI, they are positive [8]. | A shift of 2 pH units away from the nanoparticle's isoelectric point can increase zeta potential by >20 mV, significantly improving stability. |

| Ionic Strength | High salt concentration compresses the electrical double layer, shielding charges and reducing repulsion [8] [2]. | Transferring citrate-stabilized AuNPs from water to 1x PBS can induce immediate aggregation due to charge shielding [2]. |

| Temperature | Alters the dielectric constant of water and diffusion kinetics, potentially enhancing or disrupting adsorption [8]. | A 10°C increase can double the rate of protein corona formation on some nanoparticle types. |

Table 2: Impact of Surface Composition on Bacteriophage Inactivation and Biocompatibility (Mixed-Ligand Gold Nanoparticles Study) [11]

| Ligand Ratio (TMA:MUA:DDT) | Surface Charge (Zeta Potential, mV) | Phage Inactivation (log reduction) | Bacterial Viability | Mammalian Cell Viability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0:100:0 (Anionic) | Highly Negative | Low | High | >90% |

| 75:25:0 (Cationic) | Highly Positive | Moderate | Low | <50% |

| 60:20:18 (Mixed) | Moderately Positive | High (7 log) | >90% | >90% |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Enhancing Electrostatic Adsorption via Polymer Coating

This protocol describes wrapping nanoparticles with cationic polyethyleneimine (PEI) to create a positively charged surface for enhanced adsorption of negatively charged biomolecules like DNA or RNA [8].

Materials:

- Nanoparticle Core: e.g., silica, gold, or polymeric nanoparticles.

- Polymer: Branched or linear Polyethyleneimine (PEI), MW ~25,000.

- Buffer: 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4.

- Equipment: Centrifuge, vortex mixer, sonication bath, dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument.

Step-by-Step Method:

- Preparation: Dialyze or dilute the base nanoparticles in 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) to a known concentration (e.g., 1 mg/mL).

- Mixing: Add an aqueous solution of PEI dropwise to the nanoparticle suspension under vigorous vortexing. A typical starting weight ratio for NP:PEI is 1:1.

- Incubation: Allow the mixture to incubate at room temperature for 30-60 minutes with gentle shaking.

- Purification: Centrifuge the PEI-coated nanoparticles to remove unbound polymer (e.g., 15,000 rpm for 15 minutes). Resuspend the pellet in HEPES buffer.

- Characterization: Characterize the successful coating by measuring the zeta potential. A successful coating will show a significant shift towards highly positive values (e.g., from -30 mV to +40 mV). DLS can confirm an increase in hydrodynamic diameter [8].

Protocol 2: Investigating Protein Corona Formation Using Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs)

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, details how to form and analyze the protein corona on surfactant-stabilized SLNs [9].

Materials:

- Nanoparticles: Stearic acid SLNs stabilized with Tween 80 and SDS [9].

- Protein Source: Foetal Bovine Serum (FBS) or purified Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA).

- Media: Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM).

- Reagents: Bradford Assay reagents, Tris-HCl-SDS elution buffer (1 M, pH 7.4), PBS.

- Equipment: Centrifuge, UV-Vis spectrophotometer, incubator shaker.

Step-by-Step Method:

- Incubation: Incubate the freshly prepared SLNs with 5% FBS (in DMEM) for a set duration (e.g., 30 minutes to 48 hours) at 37°C with shaking at 100 rpm [9].

- Isolation: Centrifuge the nanoparticle-protein corona complexes at high speed (e.g., 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes) to separate them from unbound proteins.

- Washing: Gently wash the pellet twice with PBS (pH 7.4) to remove loosely associated proteins (soft corona).

- Elution: Resuspend the final pellet in Tris-HCl-SDS elution buffer to dissociate the tightly bound hard corona proteins from the nanoparticle surface.

- Quantification: Use the Bradford Assay with a BSA standard curve to quantify the total amount of protein eluted, thus determining the extent of corona formation [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimentation | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI) | Cationic polymer used to impart a high positive surface charge on nanoparticles, enabling strong electrostatic adsorption of nucleic acids and anionic proteins [8]. | Creating non-viral gene delivery vectors. |

| Poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) (PVP) | Non-ionic polymeric stabilizer that provides steric hindrance, preventing nanoparticle aggregation under challenging conditions like high ionic strength or the presence of aggregating gases [7]. | Stabilizing gold nanoparticles during sol-gel synthesis for aerogel composites. |

| Tween 80 & SDS | Surfactant pair used to stabilize lipid nanoparticles. Their ratio directly influences surface charge and, consequently, the composition and thickness of the adsorbed protein corona [9]. | Formulating solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) with controlled protein adsorption profiles. |

| Phosphatidylcholine | A small molecule lipid used to modulate the protein corona composition. It competitively binds to abundant proteins like albumin, thereby enriching the corona with lower-abundance proteins for improved proteomic analysis [10]. | Enhancing depth of plasma proteome profiling in biomarker discovery. |

| Mixed Ligands (TMA, MUA, DDT) | Used to engineer nanoparticle surface properties with precise ratios of positive charge (TMA), negative charge (MUA), and hydrophobicity (DDT). This allows for fine-tuning biological interactions for applications like selective pathogen inactivation [11]. | Creating broad-spectrum antiviral/antibacterial nanoparticles with high host biocompatibility. |

Mechanisms and Workflows

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Nanoparticle Aggregation

Nanoparticle aggregation is a critical issue that can severely compromise drug delivery systems. The table below outlines common problems, their root causes, and definitive solutions.

| Problem | Root Cause | Solutions & Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Aggregation in biological fluids (e.g., blood) | High ionic strength shielding surface charge; protein corona formation [13]. | Use steric stabilization (e.g., PEGylation) instead of charge stabilization [2]. Carefully manipulate nanoparticle physicochemical build-up [13]. |

| Aggregation during storage or handling | Freezing; over-concentrating; incorrect pH; excessive centrifugal force [2]. | Store at 2°-8°C; maintain pH within recommended range; avoid over-concentration; follow advised centrifugation speeds [2]. |

| Uncontrolled aggregation for SERS substrates | Conventional chemical inducers (e.g., salts) cause uncontrolled aggregation and precipitation [14]. | Employ centrifugation-induced aggregation as a controlled, non-chemical method for creating stable colloidal aggregates [14]. |

| Particle flocculation (reversible) | Changes in pH or charge shielding causing visible precipitation [2]. | Adjust pH to recommended range; apply gentle sonication; alter surface chemistry via PEGylation [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is nanoparticle aggregation a major concern for the clinical translation of nanomedicines?

Aggregation negatively impacts every stage of drug delivery. It can reduce cellular uptake, decrease the percentage of nanoparticles reaching the target site (with one meta-analysis finding only 0.7% success rate), and even cause safety issues like vascular thrombosis [13]. Furthermore, aggregates can be recognized as foreign material by the immune system, triggering immunogenic responses that can lead to adverse effects and rapid clearance from the body [15]. These challenges contribute significantly to the high attrition rate of nanomedicines in clinical trials [16].

Q2: My citrate-stabilized gold nanoparticles aggregated after I resuspended them in PBS buffer. What happened and how can I prevent this?

This is a classic example of aggregation due to charge shielding. Citrate-stabilized nanoparticles are charge-stabilized. The high ionic strength of PBS buffer compresses the electrical double layer around the particles, neutralizing the repulsive forces that keep them apart. The van der Waals forces then take over, causing the particles to stick together [2]. To prevent this, use sterically stabilized nanoparticles (e.g., PEGylated particles) for applications involving buffers or biological fluids. The polymer brush creates a physical barrier that prevents particles from coming into close contact [2].

Q3: What are the most reliable methods to characterize the size and extent of nanoparticle aggregation?

A combination of techniques is recommended, as each has strengths and limitations [17].

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Provides the hydrodynamic size distribution but is highly sensitive to aggregates, which can skew results. It infers size distribution from a correlation function rather than measuring it directly [18].

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Tracks the Brownian motion of individual particles, offering size and concentration data. It is less skewed by a small number of aggregates than DLS [18] [17].

- Electron Microscopy (EM): Offers direct visualization for precise size and morphological data. For a robust statistical analysis, use 2D Class Averaging (2D-CA), an image processing technique that automates particle identification and sizing from micrographs, providing ensemble-like data with single-particle resolution [18].

Q4: Besides PEG, what other strategies can improve nanoparticle stability and reduce immunogenicity?

The field is actively developing alternatives to PEG due to concerns about anti-PEG antibodies. Promising strategies include the use of zwitterionic polymers or poly(2-oxazoline) as non-PEG stealth coatings [16]. The core design of the nanoparticle is also crucial; meticulous selection of materials and surface properties can optimize formulations to have the least aggregation tendency [13].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

This protocol establishes a streamlined methodology for reliable size assessment, critical for predicting drug release profiles.

- Sample Preparation: Dilute nanoparticle samples (e.g., Gold Nanoparticles in citrate buffer or Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles in deionized water) to an appropriate concentration for each instrument.

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS):

- Transfer the sample to a disposable cuvette.

- Measure the particle size distribution based on the intensity of scattered light. Note that the result is a z-average diameter and is highly sensitive to aggregates.

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA):

- Inject the sample into the viewing unit with a syringe.

- Capture a video of particles under Brownian motion.

- Use the software to track each particle's movement and calculate its hydrodynamic diameter and the sample concentration.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM):

- Deposit a drop of sample onto a carbon-coated copper grid and allow it to dry.

- Image the particles at high resolution to obtain direct visual data on size and morphology.

- Data Analysis: Compare the size distributions obtained from all three techniques. NTA often emerges as a versatile method for rapid assessment due to its broad size range and concentration capabilities, while TEM provides ground-truth morphological data.

This protocol provides a controlled, non-chemical method to create stable nanoaggregates, overcoming the limitations of salt-induced aggregation.

- Synthesis of Uniform β-cyclodextrin-stabilized AgNPs (β-CD@AgNPs):

- Mix 15 mL of 0.013 M glucose, 15 mL of 0.01 M NaOH, and 30 mL of 0.015 M β-cyclodextrin solution.

- Heat the mixture with constant stirring (400 rpm).

- At 60°C, infuse 0.01 M AgNO3 solution at a precisely controlled rate of 0.8 mL/min using a syringe pump.

- Cool the solution to room temperature after the reaction is complete.

- Centrifugation-Induced Aggregation:

- Transfer 1 mL of the β-CD@AgNPs solution to a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube.

- Centrifuge at 15°C and 9000 rpm for 15 minutes.

- Carefully remove 995 µL of the supernatant.

- Re-disperse the remaining pellet in 100 µL of deionized water to obtain the stable colloidal aggregates.

Signaling Pathways in Nanoparticle Immunogenicity

The following diagram illustrates the key innate immune pathways activated by lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), which can influence both vaccine efficacy and adverse effects.

Innate Immune Pathways Activated by LNPs [15]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key materials and their functions for developing stable nanoparticle formulations.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| PEGylated Lipids | Provides steric stabilization, creating a hydrophilic barrier that reduces protein adsorption and aggregation in biological fluids [2]. | Anti-PEG antibodies can cause accelerated blood clearance and hypersensitivity upon repeated dosing [16]. |

| Ionizable Lipids | A crucial component of LNPs; enables RNA encapsulation and facilitates endosomal escape for cytoplasmic delivery [15]. | The structure influences both the efficacy and the immunogenic profile of the nanoparticle [15]. |

| Zwitterionic Polymers | Emerging alternative to PEG for stealth coatings; create a hydration layer to resist fouling and reduce immunogenicity [16]. | May offer a solution to the limitations of PEGylation, such as immunogenicity after repeated administration. |

| β-Cyclodextrin (β-CD) | Acts as a stabilizer during synthesis. Can form stable colloidal aggregates via centrifugation for applications like SERS [14]. | Provides a non-chemical, controlled method for creating functional aggregates, unlike unstable salt-induced aggregation. |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | A biodegradable polymer used for controlled drug release and forming polymeric nanoparticles [16]. | Offers excellent chemical flexibility but can face challenges with batch-to-batch variability during scale-up [16]. |

| Citrate Stabilizer | A common charge stabilizer for gold and other noble metal nanoparticles, providing electrostatic repulsion [2]. | Unsuitable for high ionic strength environments (e.g., PBS); leads to aggregation. Best for simple aqueous suspensions [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Nanoparticle Aggregation

This guide addresses common experimental challenges related to nanoparticle aggregation and provides evidence-based solutions to improve the stability of your formulations.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid aggregation in biological fluids | Protein corona formation; Electrostatic destabilization | Surface decoration with PEG or PVP; Use of anionic surfactants; Ensure excess negative surface charges. | [19] |

| Poor targeting & retention at tumor site | Incorrect nanoparticle size; Insufficient EPR effect | Optimize size to 10-100 nm (ideal: 75-100 nm for oral); Leverage passive targeting via leaky tumor vasculature. | [19] [20] |

| Low cellular uptake & endocytosis | Excessive nanoparticle size after aggregation; Incorrect surface charge | Design smaller, cationic nanoparticles for improved uptake at the cancer cell interface. | [19] |

| Inconsistent synthesis results | Uncontrolled reaction conditions; Unstable reducing agents | Employ green synthesis methods using plant extracts; Precisely control temperature, pH, and reactant concentrations. | [21] [22] |

| Inefficient drug release at target | Successful accumulation but unsuccessful payload release | Implement stimuli-responsive designs (e.g., pH-sensitive); Engineer for specific subcellular localization. | [23] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is nanoparticle aggregation a significant problem in cancer therapeutics? Aggregation prevents nanoparticles from reaching their intended target site within the body. In biological environments, proteins and electrolytes cause nanoparticles to clump together. This clumping changes their size, surface properties, and ability to move, leading to failed drug delivery and hindering clinical translation [19].

2. What are the key nanoparticle characteristics to prevent aggregation? Three key characteristics are critical:

- Size: Maintain a size typically between 10-100 nm. For oral delivery, 75-100 nm is ideal [19] [20].

- Surface Charge: Aim for an excess negative surface charge (zeta potential), especially in a fasting state, to promote electrostatic repulsion [19].

- Steric Hindrance: Coat nanoparticles with large, hydrophilic polymer chains like Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) or polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) to create a physical barrier that prevents particles from coming too close [19] [20].

3. Is aggregation always detrimental, or can it be beneficial? While generally a problem during synthesis and transit, controlled aggregation can sometimes be beneficial. In the tumor microenvironment, some aggregation can enhance nanoparticle retention and subsequent uptake by cancer cells [19]. The key is to control where and when it happens.

4. What is the difference between passive and active targeting?

- Passive Targeting: Relies on the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect. Nanoparticles accumulate in tumor tissue because of its leaky blood vessels and poor lymphatic drainage [20] [23].

- Active Targeting: Involves attaching ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides) to the nanoparticle surface that specifically bind to receptors overexpressed on cancer cells, promoting cellular uptake [23].

5. Are chemical synthesis methods the only option for creating nanoparticles? No. Green synthesis is a developing and advantageous alternative. It uses biological organisms like plants, bacteria, or fungi to reduce metal ions. This method is more eco-friendly, cost-effective, clean, and safe compared to traditional chemical methods that often use hazardous reagents [21] [22].

Quantitative Parameters for Nanoparticle Design

The following table summarizes key design parameters to minimize aggregation and maximize therapeutic efficacy, as identified in recent research.

| Parameter | Optimal Range / Type | Functional Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Size | 10-100 nm (General); 75-100 nm (Oral) | Prevents clearance; enables EPR effect; facilitates endocytosis. |

| Surface Charge (Zeta Potential) | Negative (Anionic), particularly in fasting state | Enhances stability via electrostatic repulsion; reduces opsonization. |

| Surface Coating | PEG, PVP, Citrate, Anionic Surfactants | Provides steric hindrance; prevents aggregation & protein corona formation. |

| Targeting Mechanism | Passive (EPR) & Active (Ligands) | Combines tissue-level accumulation with specific cellular uptake. |

| Synthesis Route | Green Synthesis (Biological) | Reduces pollution & energy consumption; improves safety & biocompatibility. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Aggregation in Simulated Biological Fluids

Purpose: To evaluate the colloidal stability of nanoparticles under conditions that mimic the in vivo environment.

Materials:

- Nanoparticle suspension

- Simulated biological fluids (e.g., simulated lung fluid for pulmonary delivery, fasting/fed state simulated intestinal fluid)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) / Zetasizer

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer

Method:

- Preparation: Dilute the nanoparticle suspension in the selected simulated biological fluid and in PBS as a control. Typical nanoparticle concentration should be relevant to the intended application.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixtures at 37°C under gentle agitation to simulate physiological conditions.

- Time-Point Measurement: At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours), withdraw aliquots from each mixture.

- Size & Zeta Potential: Measure the hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI) using DLS. Measure the zeta potential using electrophoretic light scattering. A significant increase in size and PDI over time indicates aggregation.

- Spectral Analysis: Use UV-Vis spectroscopy to monitor shifts in the surface plasmon resonance (for metal NPs) or changes in absorbance, which can also indicate aggregation [19].

Protocol 2: Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Plant Extract

Purpose: To synthesize silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using an eco-friendly, plant-based reducing agent.

Materials:

- Silver nitrate (AgNO₃) solution (1-10 mM)

- Plant extract (e.g., Azadirachta indica)

- Distilled water

- Magnetic stirrer with hotplate

- Centrifuge

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer, SEM/TEM

Method:

- Extract Preparation: Prepare a plant extract by boiling plant leaves in distilled water for 10-20 minutes, followed by filtration.

- Reduction Reaction: Add the plant extract dropwise to a heated (e.g., 60-80°C) AgNO₃ solution under constant stirring. A color change (to brownish) indicates the formation of AgNPs.

- Purification: Centrifuge the resulting suspension at high speed (e.g., 15,000 rpm for 20 min) to pellet the nanoparticles. Discard the supernatant and re-disperse the pellet in distilled water. Repeat 2-3 times.

- Characterization:

Aggregation Mechanisms and Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Preventing Aggregation |

|---|---|

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A hydrophilic polymer conjugated to nanoparticle surfaces to provide steric hindrance, reducing protein adsorption and immune system clearance [19] [20]. |

| Citrate | A common anionic stabilizing agent used in synthesis (e.g., for silver and gold NPs) to provide electrostatic stabilization [19] [21]. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | A synthetic polymer used as a steric stabilizer and capping agent to control growth and prevent agglomeration during synthesis [19]. |

| Plant Extracts (for Green Synthesis) | Contain phytochemicals that act as both reducing and capping agents, facilitating the eco-friendly synthesis of stable metal nanoparticles [21] [22]. |

| Anionic Surfactants | Molecules that impart a strong negative surface charge, enhancing electrostatic repulsion between nanoparticles in suspension [19]. |

| Chitosan | A natural polymer used to modify nanoparticle cores, which can improve mucus penetration, cellular uptake, and overall stability for oral delivery [23]. |

Proactive Strategies: Material and Surface Engineering to Prevent Aggregation

Nanoparticle aggregation is a fundamental challenge that can undermine the efficacy and reproducibility of nanomedicine research. This instability alters critical properties like size, surface charge, and bioreactivity, leading to inconsistent experimental results and unreliable data. Surface functionalization with polymers such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), chitosan, and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) provides a powerful strategy to counteract aggregation. These polymers create a protective steric barrier and modulate surface chemistry, enhancing colloidal stability, biocompatibility, and functionality for drug delivery, imaging, and antimicrobial applications. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting and protocols to help researchers effectively employ these coatings, directly addressing common experimental pitfalls in nanoparticle synthesis research.

Research Reagent Solutions: Core Materials and Their Functions

The following table outlines essential reagents used in the synthesis and stabilization of nanoparticles with PEG, Chitosan, and PVP.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Nanoparticle Surface Decoration

| Reagent | Primary Function in Surface Decoration | Key Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Provides biocompatibility, mucoadhesion, and antimicrobial properties; cationic nature allows for electrostatic stabilization and complexation [24] [25]. | Solubility requires acidic aqueous media (e.g., acetic acid); degree of deacetylation impacts properties [25]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Imparts "stealth" properties, reduces protein adsorption (opsonization), enhances circulation time, and improves stability via steric hindrance [24] [26]. | Molecular weight affects coating density and steric barrier thickness; functionalized derivatives (e.g., PEG-amine) are used for covalent conjugation [24]. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Acts as a stabilizing and capping agent; provides steric stabilization, enhances dispersibility, and improves biocompatibility [24] [27]. | The polymer's hydrophilic nature and film-forming capability contribute to stable coatings [24]. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Often used as a secondary stabilizer in polymer blends, improving mechanical strength and forming hydrogel matrices [28] [29]. | Contributes to the formation of a robust polymer blend matrix with other components [27]. |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | Precursor for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), which possess potent antimicrobial properties [27]. | Concentration and reaction conditions (time, temperature) critically control the size and conversion efficiency of AgNPs [27]. |

| Acetic Acid | Solvent for chitosan, protonating its amine groups to enable solubility in aqueous media [27]. | Typically used at 1-3% (v/v) concentration for complete dissolution of chitosan [27]. |

| Glycerol | Used as a plasticizer in polymer blend films to increase flexibility and prevent brittleness [28]. | Concentration must be optimized to achieve desired mechanical properties without compromising stability [28]. |

Experimental Protocols: Detailed Methodologies

Protocol 1: Synthesis of a Polymer-Blend Coating for Antimicrobial Silver Nanoparticles

This protocol details the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using a blend of Chitosan, PVP, PEG, and PVA, adapted from published research [27].

Objective: To synthesize and characterize a stable AgNP-polymer nanocomposite (M8Ag) with antimicrobial activity.

Materials:

- Chitosan (CS)

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)

- Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)

- Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA)

- Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃)

- Acetic acid (3% v/v aqueous solution)

- Distilled Water

Method:

- Polymer Blend (M8) Preparation:

- Dissolve PVA, PVP, and PEG separately in distilled water at a concentration of 0.02 g/mL.

- Dissolve Chitosan in a 3% acetic acid solution at a concentration of 0.01 g/mL.

- Stir and heat each polymer solution for 40 minutes to ensure complete dissolution.

- Combine the polymers in a volume ratio of PVA:PVP:PEG:CS:DI = 1:1:1:1:6.

- Stir the mixture regularly for 1 hour to achieve a homogeneous blend, labeled "M8".

Silver Nanoparticle Synthesis:

- Heat 60 mL of the M8 blend to 80°C under continuous stirring.

- Add AgNO₃ to the polymer solution. A mass of 0.15 g AgNO₃ per 60 mL M8 is recommended for high conversion efficiency [27].

- Maintain the reaction at 80°C with stirring for 10 hours. The color change indicates the reduction of Ag⁺ to Ag⁰ (elemental silver).

- Monitor the reaction progress by UV-Vis spectrophotometry, measuring aliquots hourly between 400-500 nm to track the surface plasmon resonance peak of forming AgNPs.

Characterization:

- FTIR: Confirm the presence of polymer functional groups and interaction with AgNPs.

- FE-SEM: Analyze surface morphology and determine nanoparticle size (expected ~42 nm [27]).

- XRD & EDX: Verify the crystalline phase and elemental composition of the composite.

Protocol 2: Formulation of a Tramadol-Loaded Transdermal Nanocomposite Film

This protocol describes the creation of a drug-loaded nanocomposite film for controlled transdermal delivery, showcasing the use of polymer-clay blends [28].

Objective: To prepare a chitosan-PVA-PVP/montmorillonite nanoclay composite for controlled drug release.

Materials:

- Chitosan, PVA, PVP

- Organically modified Montmorillonite (MMT) nanoclay

- Tramadol HCl (model drug)

- Glycerol (plasticizer)

- Distilled Water

Method:

- Solution Preparation:

- Dissolve Chitosan, PVA, PVP, and glycerol in distilled water with constant stirring.

- Add the desired mass of nanoclay (e.g., 0.075 g - 0.25 g [28]) to the polymeric solution and stir for 15 minutes.

- Add the drug (Tramadol HCl, e.g., 0.375 g [28]) to the mixture.

- Agitate the final mixture at 60°C for 30 minutes until a homogeneous solution is obtained.

Film Casting:

- Pour the solution into Petri dishes.

- Dry in an oven at 50°C for 24 hours to form thin, solid films.

Characterization & Pharmaceutical Testing:

- FTIR: Check for compatibility between components and successful drug encapsulation.

- TGA & XRD: Assess thermal stability and crystalline behavior.

- SEM: Examine film morphology and uniformity of drug and nanoclay dispersion.

- Swelling, Dissolution, and Permeation Studies: Evaluate the drug release profile and the influence of PVA/PVP concentration on release kinetics.

The workflow for preparing and characterizing these stable, polymer-coated nanoparticles is summarized below.

Diagram 1: General workflow for the synthesis and characterization of polymer-coated nanoparticles.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my chitosan solution cloudy or forming gel clots? A: This indicates incomplete dissolution. Chitosan requires a sufficiently acidic environment to protonate its amine groups. Ensure you are using an adequate concentration of acetic acid (e.g., 1-3% v/v) and allow sufficient time for stirring. The complete solubilization of chitosan is achieved when the stoichiometric ratio of acid to chitosan amine groups is appropriate, typically around [AcOH]/[CS-NH₂] = 0.6 [25].

Q2: My PEG-coated nanoparticles are still aggregating in biological media. What could be wrong? A: The "stealth" effect of PEG is highly dependent on its surface density and molecular weight. Aggregation in complex media suggests the steric barrier may be insufficient. Consider using a higher molecular weight PEG or optimizing your conjugation protocol to achieve a higher density of PEG chains on the nanoparticle surface [26].

Q3: Are there any biocompatibility concerns with PVP? A: PVP is generally considered biocompatible, low-toxic, and is widely used in pharmaceutical applications due to these properties [24]. However, as with any material, biocompatibility is specific to the application, dosage, and molecular weight. Always conduct application-specific cytotoxicity assays.

Q4: My drug-loaded polymer film is too brittle. How can I improve its flexibility? A: Incorporate a plasticizer like glycerol into your polymer blend formulation. As demonstrated in transdermal film research, glycerol significantly enhances the flexibility and handling properties of chitosan-PVA-PVP films without compromising their integrity [28].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Nanoparticle Surface Decoration

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid Nanoparticle Aggregation | Inadequate steric or electrostatic stabilization; insufficient coating density. | Increase polymer-to-nanoparticle ratio; use a combination of polymers (e.g., chitosan for electrostatic and PEG/PVP for steric stabilization). |

| Inconsistent Coating Thickness | Non-uniform functionalization of the nanoparticle surface; variable reaction conditions. | Ensure homogeneous mixing during synthesis; control reaction temperature and addition rate of polymers precisely. |

| Low Drug Encapsulation Efficiency | Poor interaction between drug and polymer matrix; rapid drug diffusion during synthesis. | Optimize polymer blend composition; for chitosan, exploit its cationic nature to complex with anionic drugs. Incorporate nanoclay to improve drug loading via ion-exchange [28]. |

| Poor Colloidal Stability in Serum | Protein fouling (opsonization) on the nanoparticle surface. | Improve the density and length of PEG coating to create a more effective "stealth" barrier against protein adsorption [26]. |

| Uncontrolled/Too Fast Drug Release | Polymer matrix is too hydrophilic or has large pores; insufficient cross-linking. | Adjust the ratio of hydrophilic (PVP, PEG) to more rigid (Chitosan) polymers; incorporate nanoclay as a physical cross-linker to sustain release [28]. |

Characterization Techniques and Data Interpretation

Confirming the success of surface decoration requires a combination of techniques to probe physicochemical properties and biological interactions. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between key characterization methods and the properties they verify.

Diagram 2: Key characterization techniques for analyzing polymer-coated nanoparticles.

Table 3: Key Characterization Methods for Coated Nanoparticles

| Technique | Measures | Interpretation of Success | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI). | A stable, monodisperse suspension will show a consistent size and low PDI over time. | ||

| Zeta Potential | Surface charge. | A high absolute value (> | 25 | mV) indicates good electrostatic stability. A shift after coating confirms surface modification. |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Chemical functional groups and bonds. | Appearance of characteristic polymer peaks (e.g., C-O-C for PEG) confirms the presence of the coating [27] [28]. | ||

| Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM) | Particle morphology, size, and core-shell structure. | Visual confirmation of a core-shell structure or a homogeneous polymer matrix embedding nanoparticles [27]. | ||

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Crystallinity of the nanoparticle core. | Helps distinguish the crystalline structure of the metal core from the amorphous polymer coating [27]. | ||

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) | Weight change as a function of temperature. | The weight loss step at high temperature quantifies the organic polymer content relative to the inorganic nanoparticle core [28]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How does nanoparticle surface charge influence its behavior in biological systems? Nanoparticle surface charge, often indicated by zeta potential, critically determines its interaction with biological fluids. Upon exposure to serum, nanoparticles rapidly adsorb proteins, forming a "protein corona." The surface charge mediates which proteins bind, ultimately determining which cellular receptors the nanoparticle-protein complex will engage with. For instance, cationic (positively charged) nanoparticles show enhanced cellular binding in the presence of serum proteins, often binding to scavenger receptors. In contrast, anionic (negatively charged) nanoparticles see their binding inhibited and instead bind to native protein receptors [30].

2. What is the optimal nanoparticle size for drug delivery applications? The optimal size is application-dependent, but for systemic circulation and targeting, it is generally below 200 nm. Size regulates convective transport, interaction with biological barriers, and cellular uptake mechanisms. Nanoparticles smaller than 50 nm can rapidly transverse into various tissues, while those in the 100-200 nm range are more readily taken up by the reticuloendothelial system (RES), which can target them to organs like the liver and spleen [31] [32]. A specific target for effective circulation is often a diameter of around 170 nm [32].

3. Why is hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity balance important, and how can it be optimized? The surface property of a nanoparticle determines its dispersity, stability, and interaction with biological membranes. A strong hydrophobic character can lead to irreversible agglomeration in aqueous biological fluids, reducing effectiveness and potentially increasing toxicity. Hydrophilicity can be optimized by using hydrophilic coatings or stabilizers like polyethylene glycol (PEG), polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), or cyclodextrins, which increase repulsive forces and provide a steric barrier against aggregation [33] [34] [35].

4. What are the most common causes of nanoparticle aggregation during synthesis and storage? The primary cause is the overcoming of repulsive forces by attractive van der Waals forces. This can be triggered by:

- Inadequate surface charge: A low zeta potential (typically below |±30| mV) provides insufficient electrostatic repulsion [33].

- Improper stabilizer: The absence or failure of steric stabilizers (e.g., polymers, surfactants) to create a physical barrier [34] [35].

- Environmental challenges: Exposure to physiological ionic strengths, pH shifts, or specific biomolecules can destabilize the colloidal suspension [34] [31].

5. Which techniques are essential for characterizing these key properties? Routine characterization is non-negotiable for reproducible science. Key techniques include:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): For determining hydrodynamic diameter and size distribution [30] [36].

- Zeta Potential Analysis: For measuring surface charge and predicting colloidal stability [30] [33] [36].

- Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM): For direct visualization of size, shape, and primary structure [35] [36] [14].

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: For confirming synthesis and tracking aggregation via plasmon band shifts [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Rapid Aggregation During Synthesis

Issue: Nanoparticles aggregate immediately during or after the synthesis process.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solution & Prevention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insufficient electrostatic stabilization | Measure zeta potential. A value below | ±30 mV | indicates weak repulsion [33]. | Introduce or increase the concentration of ionic stabilizers. Adjust the pH to move the surface charge further from the isoelectric point [35]. |

| Lack of steric stabilization | Check formulation for the presence of polymeric stabilizers (e.g., PVP, PEG). | Incorporate a steric stabilizer like PVP (for polyol synthesis) or PEG (for aqueous systems) to create a physical barrier against aggregation [34] [35]. | ||

| Too high reactant concentration | Analyze synthesis protocol; high precursor concentration can lead to rapid nucleation and uncontrolled growth. | Dilute the reaction mixture or use a syringe pump to control the precise, slow addition of precursors (e.g., AgNO₃) to ensure uniform nucleation and growth [35] [14]. |

Experimental Protocol: Polyol Synthesis of Stable Silver Nanoparticles [35]

- Materials: Silver nitrate (AgNO₃), Ethylene Glycol (EG), Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, MW 40000).

- Method:

- Mix EG and PVP in a reaction vessel with vigorous stirring (400-600 rpm).

- Heat the mixture to a constant temperature (e.g., 60°C).

- Use a syringe pump to add the AgNO₃ solution at a controlled, slow rate (e.g., 0.8 mL/min).

- Continue stirring until the reaction is complete, then cool to room temperature.

- Wash the nanoparticles with ethanol to remove by-products and excess stabilizer.

- Key Insight: The controlled addition of AgNO₃ via a syringe pump is critical for obtaining uniform size and shape, which directly enhances colloidal stability [35].

Problem 2: Size and Polydispersity Outside Target Range

Issue: Synthesized nanoparticles have a size or size distribution (PDI) that does not meet the requirements for the intended application.

Solution Strategy: Employ data-driven optimization methods like the Prediction Reliability Enhancing Parameter (PREP) to efficiently navigate complex parameter spaces. This approach can achieve target sizes (e.g., 100 nm for microgels or 170 nm for polyelectrolyte complexes) in as few as two experimental iterations [32].

Experimental Protocol: Data-Driven Size Optimization using PREP [32]

- Initial Data Collection: Compile a historical dataset from previous syntheses, recording input parameters (e.g., monomer concentration, crosslinker density, surfactant concentration) and the resulting output (hydrodynamic diameter, PDI).

- Model Building: Use latent variable modeling (LVM) to establish relationships between the input parameters and the nanoparticle size.

- Model Inversion: Input your target nanoparticle size (Y_desirable) into the PREP framework. The model will calculate the optimal synthesis parameters required to achieve this target.

- Validation: Perform the synthesis experiment using the PREP-predicted parameters and characterize the resulting nanoparticles to validate the model's prediction.

Problem 3: Instability and Aggregation in Biological Media

Issue: Nanoparticles that are stable in pure water aggregate when introduced to cell culture media or simulated biological fluids.

Possible Cause: The primary cause is the interaction with salts and biomolecules, which screen surface charge and form a protein corona, potentially bridging particles together [30] [34] [36].

Solution & Prevention:

- Enhanced Steric Stabilization: Use dense polymer brushes like PEG or polysaccharides to shield the nanoparticle surface. This steric hindrance prevents proteins from coming into direct contact with the core surface and reduces bridging flocculation [34].

- Stealth Coatings: Implement "stealth" coatings that are resistant to protein adsorption. Polydopamine coatings or hyperbranched polyglycerols have shown promise in improving stability in complex media [34].

- Pre-formation of Corona: Incubate nanoparticles in a controlled, dilute serum solution before introducing them to the full-strength media. This can allow for a more uniform, stable corona to form [36].

Experimental Protocol: Protein Corona Isolation and Analysis [36]

- Materials: Nanoparticles, Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) or blood plasma, ultracentrifuge, SDS-PAGE gel.

- Method:

- Incubate nanoparticles in MEM supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C for a predetermined time.

- Isolate the nanoparticle-protein complexes by repeated centrifugation (e.g., 16,000 × g for 10 min) and careful resuspension in water or buffer.

- Remove the supernatant after each wash to eliminate unbound proteins.

- After the final wash, suspend the pellet in an SDS-containing buffer to elute the proteins from the nanoparticle surface.

- Analyze the eluted proteins using gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) to characterize the corona composition [30] [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | A common steric stabilizer and capping agent in polyol syntheses. It adsorbs onto nanoparticle surfaces, preventing aggregation via steric hindrance [35]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A gold-standard polymer for "stealth" coating. PEGylation creates a hydrophilic layer that reduces protein adsorption (opsonization) and improves colloidal stability and circulation time [34]. |

| β-Cyclodextrin (β-CD) | A biocompatible oligosaccharide used as a stabilizer. It can form inclusion complexes and provides a hydrophilic surface, as demonstrated in the synthesis of stable silver nanoaggregates [14]. |

| Citrate | A classic anionic capping agent for gold and silver nanoparticles. Provides electrostatic stabilization by conferring a negative surface charge [34]. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Used to mimic in vivo conditions for stability and cell interaction studies. It provides the complex mixture of proteins that form the "protein corona" on nanoparticles [30] [36]. |

Workflow Diagrams

Nanoparticle Optimization Workflow

(Diagram Title: NP Optimization Workflow)

Key Property Interrelationships

(Diagram Title: Property-Bio Interaction Map)

Quick-Reference Data Tables

| Size Range | Primary Biological Behavior & Application Target |

|---|---|

| < 10 nm | Rapid renal clearance; potential deposition in respiratory tract (tracheobronchial region). |

| 10 - 50 nm | Favorable for tissue penetration and cellular internalization; can translocate to various organs. |

| 50 - 200 nm | Optimal for long circulation; primary target for RES uptake (liver, spleen). |

| > 200 nm | Primarily trapped by splenic filtration or lung capillaries; used for passive targeting to these organs. |

| Zeta Potential Range | Colloidal Stability Interpretation | Biological Interaction Notes |

|---|---|---|

| > +30 mV | Strong cationic stability. | Enhanced cellular binding in serum; binds scavenger receptors [30]. |

| +30 to +5 mV | Moderate cationic stability. | |

| -5 to +5 mV | Highly unstable (Aggregation zone). | Maximum protein adsorption and aggregation risk. |

| -5 to -30 mV | Moderate anionic stability. | Binding inhibited in serum; binds native protein receptors [30]. |

| < -30 mV | Strong anionic stability. |

| Synthesis Method | Key Parameters to Control Size | Key Parameters to Control Stability |

|---|---|---|

| Precipitation Polymerization | Monomer concentration, crosslinker density, surfactant type/conc., temperature [32]. | Functional co-monomer (e.g., acid), ionic strength, choice of initiator. |

| Polyol Synthesis | Precursor addition rate, reaction temperature, PVP concentration [35]. | PVP concentration (steric stabilizer), reaction time, washing protocol. |

| Self-Assembly (Polyelectrolyte) | Polymer concentration, charge ratio (N/P ratio), ionic strength during assembly [32]. | Polymer molecular weight, final suspension ionic strength, use of block copolymers. |

Green synthesis of nanoparticles (NPs) represents a paradigm shift in nanotechnology, moving away from conventional chemical methods that often use toxic reagents toward more sustainable biological approaches [37]. In this context, fungi and plant extracts have emerged as powerful tools, serving as natural reservoirs of bioactive compounds that act as reducing, capping, and stabilizing agents during NP formation [38] [39]. These natural capping agents are crucial for controlling nanoparticle size, shape, and stability while preventing aggregation—a significant challenge in nanoparticle synthesis and application [34].

The fundamental advantage of using these biological sources lies in their complex phytochemical composition. Plant extracts contain diverse biomolecules including polyphenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, proteins, and polysaccharides, which can reduce metal ions and subsequently cap the newly formed nanoparticles to prevent uncontrolled growth and aggregation [39] [37]. Similarly, fungal-mediated synthesis utilizes metabolites and enzymes that perform analogous functions [38]. This capping action is essential for producing stable, monodisperse nanoparticles with tailored properties for applications ranging from drug development to environmental remediation [38] [40].

Fundamental Mechanisms: How Natural Capping Agents Work

Phytochemical Roles in Nanoparticle Stabilization

Natural capping agents from plants and fungi prevent nanoparticle aggregation through two primary mechanisms: electrostatic stabilization and steric stabilization [34]. In electrostatic stabilization, charged functional groups on biomolecules create repulsive forces between nanoparticles, counteracting the attractive van der Waals forces that would otherwise cause aggregation [34]. In steric stabilization, bulky organic molecules physically prevent nanoparticles from approaching closely enough to aggregate [34].

The specific biomolecules involved vary by biological source. Plant extracts typically contain polyphenols, flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids, and proteins which provide hydroxyl, carbonyl, and amine functional groups that bind to nanoparticle surfaces [39] [37]. Fungal systems utilize proteins, enzymes, polysaccharides, and other metabolites secreted during growth that act as both reducing and capping agents [38]. These biomolecules form stable coatings on nanoparticles through coordination bonds, electrostatic interactions, or covalent bonding, creating a protective layer that maintains nanoparticle dispersion in colloidal systems [39] [34].

Diagram Title: Natural Capping Agent Mechanisms

This diagram illustrates how bioactive compounds from plant extracts and fungal metabolites facilitate both the reduction of metal ions and subsequent stabilization of nanoparticles through steric and electrostatic mechanisms, preventing aggregation.

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Nanoparticle Aggregation Issues

Problem: Rapid aggregation of nanoparticles immediately after synthesis

- Root Cause: Insufficient capping agent concentration or improper ratio between metal precursor and biological extract [38] [34].

- Solutions:

- Optimize the extract-to-metal ion ratio systematically (typically 1:1 to 1:10 v/v) [41].

- Increase phytochemical concentration by using more concentrated plant extracts [39].

- Adjust pH to optimal range (often neutral to slightly basic) to enhance capping agent functionality [38].

- Incorporate a secondary stabilization step using centrifugation and redispersion in stable medium [14].

Problem: Gradual aggregation during storage

- Root Cause: Weak capping layer or degradation of natural capping agents over time [34] [42].

- Solutions:

Size and Shape Control Challenges

Problem: Polydisperse nanoparticle population with inconsistent sizes

- Root Cause: Non-uniform reduction rates or inadequate mixing during synthesis [38] [43].

- Solutions:

- Control reaction temperature precisely (typically 25-80°C depending on system) [41].

- Implement dropwise addition of plant extract with vigorous stirring (400-600 rpm) [14].

- Use fresh plant extracts rather than stored extracts to maintain consistent reducing power [37].

- Employ ultrasonic irradiation during synthesis to improve uniformity [37].

Problem: Unpredictable or irregular nanoparticle morphologies

- Root Cause: Complex phytochemical mixtures with varying reduction potentials [39] [43].

- Solutions:

- Standardize plant extract preparation methods (drying temperature, extraction time, solvent system) [41].

- Fractionate plant extracts to isolate specific capping agents for more controlled synthesis [43].

- Optimize reaction time to prevent Ostwald ripening (larger particles growing at expense of smaller ones) [34].

Characterization and Validation Problems

Problem: Inconsistent biological activity despite similar synthesis parameters

Problem: Difficulty reproducing reported synthesis protocols

- Root Cause: Insufficient methodological details in published protocols, especially regarding capping agent preparation [37].

- Solutions:

- Contact original authors for specific details about biological material processing.

- Systemically optimize critical parameters (pH, temperature, concentration) rather than direct replication.

- Include comprehensive characterization data (TEM, DLS, zeta potential) to validate synthesis outcomes [42].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of using plant extracts over fungal systems as capping agents? Plant extracts typically offer faster reduction rates (minutes to hours compared to days for some fungal systems), easier scalability, and simpler processing requirements [37]. They contain diverse phytochemicals that provide immediate reducing and capping capabilities without the need for maintaining live cultures [39]. However, fungal systems can provide more specific enzyme-mediated reactions that offer better control over nanoparticle characteristics in some cases [38].

Q2: How can I enhance the stability of green-synthesized nanoparticles without compromising their green credentials? Optimize synthesis parameters first (pH, temperature, concentration ratios) to improve innate stability [38]. Consider using combined plant extracts that provide synergistic capping effects [37]. For additional stabilization, benign natural polymers like chitosan or cellulose derivatives can be added as secondary capping agents without significantly impacting environmental friendliness [34].

Q3: Why do my nanoparticles precipitate even with apparently sufficient capping agents? This could result from ionic strength effects in the solution that compress the electrical double layer, reducing electrostatic repulsion [34]. Check for high salt concentrations and consider dialysis or dilution. Also, verify that the capping agents themselves aren't causing flocculation through bridging effects, which can occur with high molecular weight biopolymers at specific concentrations [14].

Q4: How can I determine if my natural capping agents are effectively functionalized on the nanoparticle surface? Use Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to identify characteristic functional groups (e.g., -OH, C=O, -NH) from capping agents on the nanoparticles [41]. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) can quantify the organic capping layer amount, while zeta potential measurements indicate surface charge changes due to capping agent adsorption [42].

Q5: Can I use mixed plant extracts for better capping performance? Yes, combining different plant extracts can provide complementary capping agents with varied functional groups that enhance stability [37]. However, systematic optimization is required as complex mixtures may sometimes compete rather than cooperate, leading to inconsistent results. Start with simple 1:1 mixtures and characterize thoroughly before exploring more complex combinations [39].

Experimental Protocols for Natural Capping Agent Synthesis

Standardized Plant Extract-Mediated Synthesis Protocol

Materials Required:

- Plant material (leaves, roots, seeds, or fruits)

- Distilled/deionized water or ethanol-water mixtures as extraction solvent

- Metal salt precursor (e.g., AgNO₃, HAuCl₄, ZnSO₄)

- Standard laboratory equipment: magnetic stirrer, heating mantle, filtration apparatus, centrifugation system

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Plant Extract Preparation:

- Wash plant material thoroughly to remove surface contaminants

- Dry at 40-50°C and grind to fine powder

- Prepare extraction solvent (typically 1:10 to 1:20 plant-to-solvent ratio)

- Heat mixture at 60-80°C for 10-30 minutes with continuous stirring

- Filter through Whatman No. 1 filter paper or centrifuge at 5000 rpm for 15 minutes

- Use extract immediately or store at 4°C for short-term use [41]

Nanoparticle Synthesis:

- Prepare metal salt solution (typically 1-10 mM concentration)

- Mix plant extract with metal solution in optimized ratio (start with 1:9 to 1:1 v/v)

- Maintain reaction temperature between 25-80°C with constant stirring (400-600 rpm)

- Monitor color change indicating nanoparticle formation (e.g., pale yellow to brown for AgNPs)

- Continue reaction for 15 minutes to 24 hours depending on system

- Purify nanoparticles by centrifugation at 8,000-15,000 rpm for 15-30 minutes

- Redisperse pellet in distilled water or buffer solution [41] [14]

Characterization:

- UV-Vis spectroscopy: Confirm nanoparticle formation with characteristic SPR peaks

- FTIR: Identify functional groups of capping agents on nanoparticle surface

- TEM/SEM: Determine size, shape, and morphology

- DLS and zeta potential: Measure hydrodynamic size and surface charge stability [42]

Fungal-Mediated Synthesis Protocol

Materials Required:

- Fungal strain (e.g., Aspergillus sydowii, Penicillium chrysogenum)

- Fungal culture medium (Potato Dextrose Agar/Broth)

- Metal salt precursor

- Sterile laboratory equipment: autoclave, laminar flow hood, incubator

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Fungal Culture Preparation:

- Maintain fungal strain on agar slants at 4°C

- Inoculate in liquid medium and incubate at 25-30°C with shaking (120-150 rpm)

- Culture for 3-7 days until sufficient biomass growth

- Separate mycelial biomass by filtration or centrifugation

- Wash biomass with sterile distilled water [38]

Nanoparticle Synthesis:

- Option A (Intracellular): Suspend biomass in metal salt solution, incubate 24-72 hours

- Option B (Extracellular): Filter culture supernatant, mix with metal salt solution

- Maintain optimal pH and temperature for specific fungal system

- Monitor color change or use UV-Vis to track nanoparticle formation

- For intracellular NPs: disrupt cells using sonication or enzymatic treatment

- Purify nanoparticles through repeated centrifugation and washing [38]

Characterization:

- Same characterization techniques as plant-mediated synthesis

- Additional enzymatic assays may be needed to identify fungal enzyme involvement [38]

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Natural Capping Experiments

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Green Synthesis Using Natural Capping Agents

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Usage Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Sources | Avena fatua (wild oat), Moringa oleifera, Trachyspermum ammi, Clerodendrum inerme | Provide reducing and capping phytochemicals | Seasonal variation affects phytochemical content; standardization required [41] [39] [40] |

| Fungal Sources | Aspergillus sydowii, Penicillium chrysogenum | Produce extracellular enzymes and metabolites for capping | Require sterile culture conditions; longer synthesis time [38] |

| Metal Precursors | AgNO₃, HAuCl₄, ZnSO₄, CuSO₄ | Source of metal ions for nanoparticle formation | Concentration critically affects size and morphology [41] [40] |

| Extraction Solvents | Deionized water, ethanol, water-ethanol mixtures | Extract bioactive compounds from biological sources | Solvent polarity affects phytochemical profile; water is greenest option [37] [40] |

| Purification Materials | Centrifuge filters, dialysis membranes | Remove unreacted precursors and impurities | Multiple washing cycles often needed for high purity [14] |

| Stabilization Additives | β-cyclodextrin, citrate buffer | Enhance stability of capped nanoparticles | Should be biocompatible; may interfere with some applications [14] |

Quantitative Data Comparison of Natural Capping Agents

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Different Natural Capping Agents

| Capping Agent Source | Typical NP Size Range | Stability Duration | Common Applications | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf Extracts (e.g., Moringa oleifera) | 4-100 nm [39] | 2-8 weeks [37] | Antimicrobial, photocatalytic [39] | Rapid synthesis, easily available | Seasonal variability, complex phytochemistry |

| Seed Extracts (e.g., Ricinus communis) | 5-50 nm [39] | 4-12 weeks [37] | Drug delivery, anticancer [40] | Rich in proteins and lipids | Limited availability year-round |

| Fungal Systems (e.g., Aspergillus sydowii) | 10-80 nm [38] | 8-16 weeks [38] | Biomedical, environmental remediation [38] | Better size control, enzyme-specific | Longer culture time, sterilization required |

| Root Extracts (e.g., licorice root) | 20-100 nm [39] | 4-10 weeks [37] | Antioxidant, anticancer [39] | Unique phytochemical profiles | Harvesting damages plant |

| Fruit Extracts (e.g., Vitis vinifera) | 10-60 nm [39] | 2-6 weeks [37] | Sensors, food applications [39] | High sugar content aids reduction | Seasonal availability |

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

The application of natural capping agents extends across multiple domains, particularly in biomedical fields where biocompatibility is crucial. Green-synthesized nanoparticles with natural capping layers have demonstrated significant potential in drug delivery systems, cancer therapy, antimicrobial applications, and biosensing [38] [40]. The inherent biological activity of the capping agents can synergize with the metallic core for enhanced therapeutic effects [39].

Future research directions should address current challenges in standardization and scalability. Developing standardized protocols for characterizing capping layer composition and thickness would significantly improve reproducibility [37]. Exploring novel biological sources, particularly agricultural waste products, aligns with circular economy principles while providing cost-effective capping alternatives [39]. Additionally, engineering hybrid capping systems that combine the advantages of different biological sources could yield nanoparticles with tailored properties for specific applications [43].

As green synthesis methodologies mature, the role of natural capping agents will expand beyond simple stabilization to include functionalization for targeted applications. Understanding structure-activity relationships between specific phytochemical classes and nanoparticle properties will enable rational design of green-synthesized nanomaterials with optimized performance characteristics [39] [37].

Nanoparticle aggregation is a predominant obstacle in nanomaterial research, leading to inconsistent properties, reduced efficacy, and failed experiments. This phenomenon undermines the reproducibility essential for scientific and industrial applications, particularly in sensitive fields like drug delivery where size and surface characteristics dictate biological interactions [44]. Traditional manual synthesis methods, which rely heavily on researcher skill and are prone to human variability, struggle to control the interdependent parameters governing aggregation [45].

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and robotics presents a paradigm shift, moving from labor-intensive trial-and-error to data-driven, closed-loop optimization. These automated platforms can precisely manage reagent addition, mixing dynamics, and temperature in real-time, directly addressing the root causes of aggregation. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers leveraging these advanced systems to overcome aggregation and achieve reproducible, high-quality nanoparticles [45] [44].

Troubleshooting Guides

Aggregation During Synthesis

Problem: Synthesized nanoparticles consistently form aggregates, resulting in polydisperse solutions and unreliable characterization data.

Solutions:

- Cause: Inconsistent Mixing Dynamics. Turbulent flow and varying shear forces can cause particles to collide and fuse.

- Remedy: Implement microfluidic hydrodynamic flow focusing. This passive method creates a narrow stream of reactants surrounded by a sheath fluid, ensuring highly uniform mixing and controlled nucleation, which prevents uncontrolled particle growth and aggregation [44].