Scaling Up Nanoparticle Production for Drug Delivery: Strategies, Challenges, and Regulatory Pathways

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on scaling up nanoparticle production.

Scaling Up Nanoparticle Production for Drug Delivery: Strategies, Challenges, and Regulatory Pathways

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on scaling up nanoparticle production. It covers the foundational challenges of transitioning from lab to industrial scale, explores scalable production technologies like microfluidics and supercritical fluid processing, details strategies for troubleshooting and process optimization, and outlines the analytical and regulatory frameworks essential for demonstrating product comparability and quality. The content synthesizes current research and industry trends to offer a practical roadmap for successful clinical translation of nanomedicines.

The Scale-Up Challenge: Bridging the Gap from Lab Bench to Commercial Production

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most significant challenges when scaling up nanoparticle production for pharmaceuticals?

The primary challenges involve maintaining reproducible quality and batch-to-batch homogeneity when moving from small laboratory synthesis to industrial-scale production. Conventional small-scale lab techniques often struggle with batch-to-batch variability, and increasing the installation size introduces many difficulties in controlling nanoparticle properties such as size, surface characteristics, and drug loading capacity [1] [2]. Furthermore, achieving compatibility between the nanoparticle and the final product formulation is critical for preserving material integrity during downstream processing and ensuring stability in the final drug product [3].

Q2: Why is reproducibility so difficult to achieve during scale-up?

Reproducibility is challenging due to the intrinsic variability of the colloidal crystallization nucleation process [4]. Factors such as poor temperature control in large-volume reactors, variability of precursors, and the simultaneity of nuclei growth and agglomeration steps can lead to inconsistencies [4]. Scaling up a process often requires significant modifications to the original lab method, such as substituting centrifugation with magnetic decantation for product separation or changing the heating methodology to ensure temperature uniformity in large, viscous fluid volumes [4].

Q3: How can raw material variability impact scale-up, and how is it controlled?

Raw material variability is a critical factor. Using more affordable, commercial-grade reagents without prior purification can be part of a strategy to minimize costs for scaled-up synthesis [4]. However, the properties of the final nanoparticles are highly sensitive to the characteristics of the starting materials. Control is achieved through rigorous supplier qualification and implementing a robust synthetic process designed to be consistent despite minor variations in precursors. The process must be designed to obtain the necessary composition or phase in high yield [3].

Q4: What are the critical quality attributes (CQAs) for scaled nanoparticle batches?

Critical quality attributes for nanoparticles include [5]:

- Size, Polydispersity, and Shape: Affect stability, biodistribution, and cellular uptake.

- Surface Charge and Chemistry: Influence stability, cellular uptake, and interaction with biological systems.

- Drug Loading Capacity and Release Kinetics: Determine therapeutic efficacy.

- Stability and Biocompatibility: Ensure product integrity and safety.

- Manufacturing Reproducibility: Ensures batch-to-batch consistency.

Q5: What personal protective equipment (PPE) is recommended for handling nanomaterials?

If technical controls are insufficient to prevent the release of nanomaterials, the use of personal respiratory protection is recommended. The German Social Accident Insurance (DGUV), for example, recommends respiratory protection of filter class P3 or P2 [6]. The selection must be based on a prior risk assessment, and the mask must be fitted tightly to the face. Employers are responsible for providing basic training and implementing a hierarchy of control measures, which includes substitution, technical controls, organizational measures, and finally, personal protective equipment [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common Scale-Up Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Irreproducible Particle Size & Distribution | Inefficient mixing at large scale; variable nucleation/growth kinetics [2] [4]. | Transition to continuous manufacturing with turbulent jet mixers for rapid, efficient mixing and narrower size distribution [5]. Implement real-time Process Analytical Technology (PAT) for immediate control [5]. |

| Low Process Yield | Inefficient product separation and washing at large volumes; immature reaction conditions [4]. | Substitute centrifugation with magnetic decantation for large volumes [4]. Prolonging the high-temperature step during synthesis can also increase yield and size reproducibility [4]. |

| Particle Aggregation & Instability | Incompatible surface chemistry with the final formulation; ineffective capping agents [3]. | Co-optimize nanoparticle design with the product integrator. Use custom capping agents (e.g., silanes, thiols) for compatibility with the solvent system and to prevent agglomeration [3]. |

| Inconsistent Biological Performance | Batch-to-batch variations in critical quality attributes (CQAs) like surface charge and drug release [1] [5]. | Strictly control all CQAs through a defined and scalable process. Ensure manufacturing reproducibility is a key development parameter, not an afterthought [5] [3]. |

| Product Contamination | Erosion of milling materials (in bead milling); use of hazardous chemicals in synthesis [2]. | Employ green synthesis approaches using biological systems to reduce hazardous chemicals [7]. For milling, explore alternative size-reduction technologies like high-pressure homogenization [2]. |

Scale-Up Methodology: Thermal Decomposition for Magnetic Nanoparticles

The following protocol details a scaled-up synthesis of multi-core iron oxide nanoparticles, demonstrating how to address reproducibility and volume challenges [4].

1. Primary Workflow

2. Detailed Experimental Steps

- Reagent Preparation: In a 2 L glass beaker, homogenize the mixture using an Ultra-thurrax at 6000 rpm for 20 minutes. The molar ratio is Fe(acac)₃ : Oleic Acid (OA) : 1,2-Dodecanediol (ODA) = 1:3:2, with an iron precursor concentration of 0.1 M [4].

- Reaction Setup: Transfer the homogenized mixture to a 10 L quartz reactor. Begin overhead stirring at 100 rpm and flow nitrogen gas through the stirrer guide at 9.5 L/min. Maintain stirring and nitrogen flow for the entire process [4].

- Heating and Reflux:

- Apply 670 W of power to heat the mixture to 195°C (approx. 1 hour).

- Start reflux refrigeration and reduce power to 244 W to maintain a temperature of 200°C for 2 hours.

- Apply full power (1300 W) to reach the boiling point (~285°C). Maintain at this temperature for a variable time (5 to 120 minutes). Note: This maturation time is a critical process parameter that directly controls final particle size and microstructure [4].

- Reaction Quenching: Stop stirring and remove the heating mantle to rapidly quench the reaction while maintaining the nitrogen flow [4].

- Product Purification (Magnetic Decantation):

- Transfer the product to a 5 L glass beaker. Precipitate the nanoparticles using a mixture of n-hexane and ethanol.

- Separate the magnetic fraction by placing the beaker on a 0.5 T neodymium magnet for two days.

- Discard the supernatant. Wash the solid three times with a toluene:ethanol mixture (1:2 v/v), using sonication for 15 minutes and magnetic separation after each wash [4].

- Final Dispersion: Disperse the final purified product in a solution of oleic acid and toluene (1:7 v/v) using sonication [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Scaled Nanoparticle Synthesis

| Material | Function & Importance | Key Considerations for Scale-Up |

|---|---|---|

| Iron (III) acetylacetonate (Fe(acac)₃) [4] | Metal-organic precursor for magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. | Use affordable, commercial-grade quality (e.g., 99%) without purification to minimize cost at kilogram scales [4]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) [4] | Surfactant and stabilizing agent. Acts as a capping agent to control growth and prevent aggregation. | The molar ratio to the metal precursor is critical. It provides colloidal stability in organic solvents post-synthesis [4]. |

| 1,2-Dodecanediol (ODA) [4] | A reducing agent in the thermal decomposition synthesis. | Works in conjunction with the surfactant to control the reduction of the metal precursor and influence particle size and morphology. |

| Benzyl Ether [4] | High-boiling-point organic solvent. | Chosen for its high boiling point (~285°C) to allow for high-temperature crystal growth and for ease of purification in large-scale reactions [4]. |

| Capping Agents (e.g., silanes, thiols) [3] | Modify nanoparticle surface chemistry to ensure stability and compatibility with final product formulations. | Selection is application-specific. They can provide a strong bond to the particle or be designed for downstream removal [3]. |

Data Presentation: Scale-Up Production Methods

Table 3: Comparison of Nanoparticle Production Methods for Scale-Up

| Method | Material | Key Advantages for Scale-Up | Key Limitations & Scale-Up Hurdles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Decomposition [4] | Metals, Metal Oxides | Produces nanoparticles with excellent size homogeneity and shape control >20 nm. Uses cheaper commercial precursors at kilogram scale. | Requires modification from lab-scale (e.g., power control vs. PID, magnetic decantation vs. centrifugation). Reproducibility depends on precise control of maturation time [4]. |

| Continuous Manufacturing [5] | Lipid, Polymeric NPs | Simplified scale-up: run longer or increase flow rate for more product. Inline feedback for real-time control. Reduces unit operations and footprint. | Initial setup and integration with existing batch-based facilities can be a hurdle. Requires regulatory alignment with continuous processes [5]. |

| High-Pressure Homogenization [2] | Lipid NPs | Inherent scale-up feasibility. No use of organic solvents. | Can produce larger particles with a broader size distribution (cold process). Not suitable for thermolabile drugs (hot process). Energy-intensive [2]. |

| Supercritical Fluid Technology [2] | Polymers | Absence of residual solvent. Narrow particle size distribution. Mild operating temperatures. | Poor solvent power of CO₂. High cost and necessity for voluminous usage of CO₂ [2]. |

| Nanoprecipitation [2] | Polymers | Simple technique, low cost. Small particle size. | Difficult to control particle growth. Primarily applicable to lipophilic drugs only. Limited to water-miscible solvents [2]. |

Advanced Technical Schematics

Quality Attribute Interrelationships

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most critical particle characteristics to monitor during scale-up? Particle Size, Polydispersity Index (PDI), and Drug Loading are paramount [8] [9]. Size and PDI affect stability, biological fate, and therapeutic efficacy, while drug loading impacts potency and cost-effectiveness.

Why does particle size often increase when I move from a small batch to a larger one? This is a common challenge due to changes in mixing efficiency and energy input [9]. In large-scale vessels, mixing is less efficient and homogenous than in lab-scale equipment like sonicators or small microfluidics chips. This can lead to incomplete particle formation and aggregation, resulting in larger particle sizes and broader size distribution (higher PDI) [2] [9].

How can I improve batch-to-batch consistency during scale-up? Implementing advanced manufacturing technologies and highly controlled processes is key [9]. This includes moving from manual methods to automated, continuous processes like scalable microfluidics or high-pressure homogenization. These technologies offer better control over mixing parameters, leading to more reproducible particle characteristics [2] [10].

My drug loading efficiency drops at a larger scale. What could be the cause? Inefficient mixing at a large scale can lead to incomplete encapsulation of the active ingredient [9]. Additionally, if the scale-up process introduces new shear forces or temperature gradients that degrade the drug or the nanoparticle matrix, loading efficiency can decrease [1].

What analytical techniques are essential for characterizing particles during scale-up? A combination of orthogonal techniques is recommended [11]. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) is common for measuring hydrodynamic size and PDI [12]. Laser Diffraction covers a broader size range [13]. Electron Microscopy (e.g., SEM) provides direct visualization of particle size, morphology, and potential aggregation [13] [11].

Troubleshooting Common Scale-Up Issues

| Problem | Potential Root Cause | Suggested Solutions & Experimental Checks |

|---|---|---|

| Increased Particle Size [9] | Inefficient mixing during formulation; altered energy input during size reduction steps (e.g., extrusion, homogenization). | Experiment: Compare different mixing speeds/geometries in large tank. Use a scalable inline homogenizer instead of batch mixing. Check: Ensure extrusion/homogenization parameters (pressure, cycles) are optimally adjusted for higher volume [2]. |

| High Polydispersity Index (PDI) [9] [14] | Non-uniform mixing causing inconsistent particle formation; broad residence time distribution in continuous reactors. | Experiment: Use a continuous manufacturing process (e.g., microfluidics, annular jet) for more uniform mixing. Check: Characterize samples at multiple time points during the process to identify the source of heterogeneity [10]. |

| Low Drug Loading Efficiency [9] | Active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) degradation due to process-related stress (shear, temperature); inefficient encapsulation due to rapid precipitation. | Experiment: Protect API from process stress (e.g., lower temperature, reduce harsh solvents). Optimize the drug-to-excipient ratio for the new scale. Check: Analyze the API stability and final product composition using HPLC [1]. |

| Poor Batch-to-Batch Consistency [1] [9] | Minor, unaccounted-for variations in raw material quality, process parameters, or environmental conditions. | Experiment: Implement a rigorous Quality by Design (QbD) approach. Establish strict specifications for raw materials and tighter control limits for critical process parameters (CPPs). Check: Use advanced process analytical technology (PAT) for real-time monitoring [10]. |

Experimental Data: Quantifying Scale-Up Effects

The following table summarizes key parameters from a study on liposomal nanoparticles, demonstrating how formulation and process variables directly impact particle characteristics [14].

Table 1: Effect of Formulation and Process Parameters on Liposomal Nanoparticles [14]

| Factor | Impact on Particle Size | Impact on PDI | Experimental Protocol Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sonication Time | Decreasing time led to larger particles. Optimal time (∼30 min) minimized size [14]. | Longer sonication (up to a point) reduced PDI to <0.2 [14]. | Liposomes were prepared via thin-film hydration and bath sonication. Size/PDI were measured by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). |

| Extrusion Temperature | Temperature near 60°C was critical for achieving minimum particle size [14]. | Temperature control was essential for maintaining a low PDI [14]. | After sonication, liposomes were extruded through polycarbonate filters (400 nm to 50 nm) using a thermobarrel extruder at a temperature above the lipid phase transition temperature (Tm). |

| Lipid Composition | Composition (A) achieved smaller min. size (116.5 nm) than composition (B) (130.0 nm) [14]. | Both compositions could achieve a PDI < 0.2 with optimized other factors [14]. | Two compositions were tested: (A) HSPC:DPPG:Chol:DSPE-mPEG2000 (55:5:35:5) and (B) HSPC:Chol:DSPE-mPEG2000 (55:40:5). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Liposomal Nanoparticle Formulation [14]

| Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| HSPC (Hydrogenated Soy Phosphatidylcholine) | The primary phospholipid component forming the structural bilayer of the liposome. |

| Chol (Cholesterol) | Incorporated into the lipid bilayer to improve membrane stability and rigidity. |

| DPPG (Dipalmitoylphosphatidylglycerol) | A negatively charged lipid used in Composition A to influence surface charge and stability. |

| DSPE-mPEG2000 | A PEGylated lipid used to create a "stealth" coating, prolonging circulation time by reducing immune clearance. |

| Chloroform | Organic solvent used to dissolve lipids initially for thin-film formation. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Aqueous hydration buffer used to hydrate the lipid film and form liposomes. |

Visualizing the Relationship Between Scale-Up Parameters and Particle Characteristics

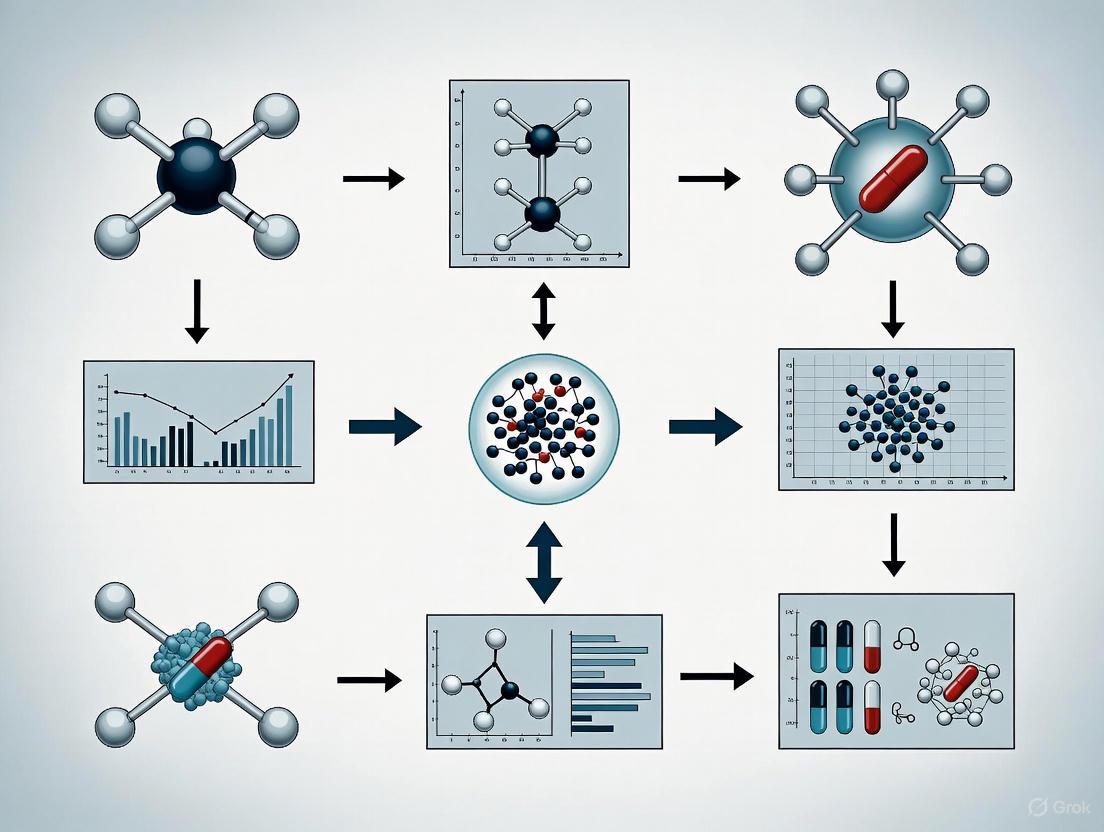

The diagram below illustrates the core principles of how critical process parameters (CPPs) during scale-up directly impact critical quality attributes (CQAs) of nanoparticles, and the subsequent analytical techniques required for characterization.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent nanoparticle characteristics (size, polydispersity, encapsulation efficiency) between production batches.

| Observable Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Diagnostic Action |

|---|---|---|

| Variable particle size and distribution | Fluctuations in critical process parameters (CPPs) like pressure, mixing speed, or solvent diffusion rate [2] | Audit process logs for parameter drift; implement real-time monitoring of homogenization pressure or stirring rates. |

| Inconsistent drug loading/encapsulation efficiency | Changes in raw material properties (e.g., polymer molecular weight, lipid purity) [15] [16] | Review Certificates of Analysis (CoA) for raw material lots; conduct pre-production characterization of key material attributes. |

| Changes in biological performance (potency) despite similar physical attributes | Inadequately controlled critical quality attributes (CQAs) like dsRNA impurity in mRNA products or surface morphology [17] | Expand analytical characterization to include potency assays and product-related impurity profiling (e.g., dsRNA dot blot). |

Guide 2: Addressing Variability in Advanced Cell Models

Problem: High batch-to-batch variability in 3D organoid models, leading to irreproducible experimental data.

| Observable Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Diagnostic Action |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomic and metabolic drift in organoids over time | Use of late-passage neuroepithelial stem cells (NESCs) during organoid generation [18] | Limit the passage number of starter NESC cultures; use early-passage cells (e.g., p10-p15) for new organoid batches. |

| High variance within and between organoid batches | Interaction of donor biological factors (disease, sex) with culture conditions; inherent complexity of protocols [18] | Implement a balanced experimental design that accounts for donor, sex, and batch as independent variables in statistical analysis. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common root causes of batch-to-batch variation in pharmaceutical manufacturing? The causes are multifaceted and can originate from raw material variability and process parameter inconsistencies. Natural variations in active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), such as differences in particle size and packing density, significantly impact processability [15]. Furthermore, inconsistencies in critical process parameters (CPPs) during unit operations, such as homogenization pressure or mixing dynamics, can lead to variable product quality [2].

Q2: How can we control variation when scaling up nanoparticle production from lab to industrial scale? Successful scale-up requires a deep process understanding rooted in Quality by Design (QbD) principles. This involves identifying and tightly controlling Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) that influence Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs). Techniques like high-pressure homogenization and extrusion are favored for their scalability, but process parameters must be meticulously defined and monitored [2]. Implementing Process Analytical Technology (PAT) for real-time monitoring is encouraged by regulatory guidelines to enhance understanding and control [15].

Q3: Our lab produces midbrain organoids for disease modeling, but results are not reproducible. What is the most critical factor to control? Your most critical factor is likely the passage number of the starter cells. Research shows that the passage of neuroepithelial stem cells (NESCs) has a greater impact on transcriptomic variance than the organoid generation batch itself. Using late-passage NESCs can double the batch-to-batch variability. Prioritize using early-passage NESC cultures to ensure phenotypic stability and reproducible results [18].

Q4: What analytical strategies can help identify the source of batch-to-batch variation? A combination of univariate analysis of specific attributes and multivariate data analysis is highly effective. For powders, combining laser diffraction (for particle size) with low-pressure compression (for packing density) can reveal interactions that are not apparent when looking at single parameters [15]. For complex processes, building multivariate "golden batch" models can help detect deviations in real-time and pinpoint their root causes [19].

Q5: What are the key CQAs for lipid nanoparticle (LNP) products containing mRNA? Key CQAs for mRNA/LNP products fall into several categories [17]:

- Purity & Impurities: mRNA integrity, double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) content, residual nucleotides.

- Product Characteristics: Particle size, polydispersity index, encapsulation efficiency, mRNA concentration.

- Potency: Protein expression capability and functionality of the encoded protein.

- Safety: Sterility, endotoxin.

Experimental Protocols for Variability Analysis

Protocol 1: Assessing Powder Processability via Packing Density and Particle Size

Objective: To identify the source of batch-to-batch variation in the processability of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) by evaluating the combined effect of particle size and packing behavior [15].

Materials:

- Texture Analyzer (e.g., TA-XT2) fitted with a die and flat-faced punch

- Laser Diffraction Particle Size Analyzer

- Powder samples from multiple API batches

Methodology:

- Low-Pressure Compression:

- Carefully fill the die with a known mass of powder.

- Compress the powder at a low pressure (e.g., < 1 MPa) and record the compression profile.

- Calculate the specific density at 0.2 MPa (d0.2) from the compression data. This parameter is highly sensitive to particle size and shape and correlates well with tapped density.

Particle Size Distribution:

- Disperse a representative powder sample in a suitable medium.

- Analyze the sample using laser diffraction to obtain volume-based particle size distribution.

- Record key parameters: d[4,3] (volume mean diameter), d[3,2] (surface area mean diameter), and d(v,0.1).

Data Analysis:

- Perform multivariate statistical analysis (e.g., Principal Component Analysis) on the dataset containing d0.2 and all particle size parameters.

- The interaction between particle size and packing density (d0.2) will often reveal the root cause of variability that is not apparent from univariate analysis.

Protocol 2: Monitoring a Batch Process Using Multivariate Analysis

Objective: To reduce batch-to-batch variability in a manufacturing process (e.g., for a Botanical Drug Product) by building a "golden batch" model for real-time monitoring and control [19].

Materials:

- Multivariate Data Analytics Software (e.g., SIMCA)

- Historical process data from multiple batches

- Real-time data monitoring system (e.g., SIMCA-online)

Methodology:

- Data Gathering:

- Collect and store data on all relevant process variables (e.g., temperatures, flow rates, pH) from historical batches in a centralized database.

Model Building:

- Use multivariate analytics to identify batches with "good" behavior and performance.

- Build a "golden batch" model using the process data from these reference batches. This model defines the normal operating space.

Real-Time Monitoring:

- Deploy the model with a real-time monitoring tool.

- As new batches are produced, the tool compares the live process data to the golden batch model.

Intervention:

- The monitoring tool provides an easy-to-understand visualization of process deviations.

- Operators can take corrective actions when the process shows a significant deviation from the golden batch trajectory, preventing the production of a failed or out-of-spec batch.

Process Visualization

Diagram: Batch Variability Analysis Workflow

Diagram: Nanoparticle Scale-Up Control Strategy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Variability Control |

|---|---|

| Laser Diffraction Particle Size Analyzer | Provides quick and reproducible measurements of particle size distribution, a key physical attribute affecting processability and performance [15]. |

| Texture Analyzer with Compression Cell | Used for low-pressure compression tests to determine the specific packing density (d0.2) of powders, which is sensitive to variations in particle size and shape [15]. |

| Certificates of Analysis (CoA) | Documents provided by suppliers that confirm the quality, purity, and specific lot-to-lot data for raw materials, enabling traceability and root cause investigation [16]. |

| Microfluidizer | A high-shear fluid processor used for nanoparticle production, allowing precise control over particle size by managing pressure and collision dynamics [2]. |

| Multivariate Data Analysis Software (e.g., SIMCA) | Enables the identification of complex interactions between material attributes and process parameters that are not visible through univariate analysis, crucial for building golden batch models [15] [19]. |

Sterility and Contamination Control for Sensitive Payloads like RNA and DNA

FAQs: Addressing Common Concerns in Scaling Up Production

FAQ 1: What are the primary sources of DNA/RNA contamination in nanoparticle formulations, and how can they be controlled during scale-up?

The primary sources of contamination are residual process-related impurities. For DNA, this includes genomic DNA from the host organism (e.g., E. coli) and protein impurities from the production system [20]. For RNA, common impurities include truncated RNA fragments, double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), and enzymes from the in vitro transcription process [20]. Control during scale-up requires robust, scalable purification methods like tangential flow filtration and chromatography to remove these specific impurities effectively [20].

FAQ 2: Why is sterile filtration particularly challenging for lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) encapsulating RNA or DNA?

Sterile filtration, which typically uses 0.2 µm pore size membranes, is challenging because mRNA-LNPs often have diameters ranging from 50–200 nm [20]. The size of these particles is very close to the pore size of the sterilizing-grade filters, which can lead to membrane fouling, filter blockage, and significant challenges in processing, especially at a large scale [20].

FAQ 3: How can terminal sterilization methods like autoclaving affect sensitive nanoparticle formulations?

Autoclaving, which uses high-pressure steam at around 120 °C, can cause several undesirable effects on nanoparticle formulations [21]. These include particle aggregation, changes in size distribution (e.g., via Ostwald ripening), and instability of the payload. The impact heavily depends on the nanoparticle's composition and capping materials; for instance, lipid-based nanoparticles may tolerate autoclaving better than some metal nanoparticles [21].

FAQ 4: What are the key considerations for ensuring the sterility of final nanoparticle products without compromising their stability or payload integrity?

The key is selecting a sterilization method compatible with the formulation. For heat- or radiation-sensitive nanoparticles, sterile filtration is the preferred method, provided the particle size is suitable [21]. For larger particles, aseptic processing throughout the entire manufacturing chain is critical. Furthermore, the choice of method must be validated to ensure it does not alter critical quality attributes like particle size, zeta potential, polydispersity index (PDI), or drug release profile [21].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Low Yield or Degraded RNA/DNA Payload

| Potential Cause | Recommended Action | Preventive Measures for Scale-Up |

|---|---|---|

| Endogenous Nucleases | Immediately inactivate intracellular RNases upon cell lysis. Use proper cell or tissue storage conditions (e.g., flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen and storage at -70 °C) [22]. | Implement rapid, continuous processing systems to minimize hold times. Ensure storage vessels and transfer lines are maintained at controlled temperatures. |

| Inefficient Homogenization | Homogenize tissue samples thoroughly. If a centrifugation step is used prior to chloroform addition, a white mucus-like pellet is expected; a tan-colored precipitate indicates incomplete cell lysis [22]. | Use scalable, high-shear homogenizers and validate homogenization efficiency for each tissue type and batch size. |

| Improper Precipitation | For samples rich in proteoglycans/polysaccharides, use a high-salt precipitation solution (0.8 M sodium citrate, 1.2 M NaCl) with isopropanol to keep contaminants soluble [22]. | Standardize precipitation conditions and solution quality. Implement in-process controls to monitor precipitation efficiency. |

Issue 2: Persistent DNA Contamination in RNA Isolations

| Potential Cause | Recommended Action | Preventive Measures for Scale-Up |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete DNase Digestion | Include an amplification-grade DNase I treatment step after the initial RNA isolation [22]. | Incorporate a validated DNase digestion step into the purification protocol and ensure sufficient mixing and residence time in flow-through systems. |

| Plasmid DNA Carryover | If isolating RNA from cells transfected with a plasmid, be aware that not all plasmid DNA may partition into the interphase/organic phase. A DNase I treatment is essential [22]. | For processes using plasmid DNA, optimize the separation conditions (e.g., chloroform addition and centrifugation) to maximize DNA removal in early stages. |

Issue 3: Problems with Sterile Filtration of Nanoparticles

| Potential Cause | Recommended Action | Preventive Measures for Scale-Up |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Size too Large | Characterize the nanoparticle hydrodynamic size. If it approaches or exceeds 200 nm, sterile filtration may not be feasible, and aseptic processing is required [21] [20]. | Implement strict controls over the nanoparticle formulation process to ensure a consistent and appropriate particle size distribution for filtration. |

| Filter Fouling/Clogging | Pre-condition the sample by filtering through a larger pore size membrane (e.g., 0.45 µm) before the final 0.2 µm sterilizing-grade filter [20]. | Use preconditioning steps as part of the standard workflow. Consider using filters with modified surfaces (e.g., polyethersulfone) that are less prone to fouling [21]. |

Data Presentation: Sterilization Methods for Nanoparticles

The table below summarizes the primary terminal sterilization methods, their mechanisms, and their impact on nanoparticles, which is critical for process design during scale-up.

Table: Comparison of Terminal Sterilization Methods for Nanoparticles

| Method | Mechanism | Optimal For | Impact on Nanoparticles | Scale-Up Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sterile Filtration [21] | Physical removal of microbes via membrane (0.2-0.45 µm). | Heat- or radiation-sensitive nanoparticles with sizes < 220 nm; liquid formulations. | Generally minimal impact. Potential for particle loss, clogging, or drug leakage for larger/delicate structures. | Filter capacity and fouling are major concerns. Requires pre-filtration. Not suitable for high-viscosity or high-solid concentrates. |

| Autoclaving [21] | Destruction of microbes by high-pressure saturated steam (~120°C). | Thermostable, aqueous nanoparticle formulations (e.g., some metal or lipid nanoparticles). | Can cause aggregation, size increase (Ostwald ripening), and payload degradation. Effect depends on capping agents. | Batch process. High energy consumption. Requires validation of heat penetration and its effect on the entire batch. |

| Ionizing Radiation (e.g., Gamma, E-beam) [21] | Destruction of microbial DNA by high-energy photons/electrons. | Heat-sensitive solids and suspensions. | Can generate free radicals, damaging polymer matrices and affecting drug release profiles. | Requires specialized, regulated facilities. Dosimetry must be calibrated to ensure sterility without degrading the product. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolation and Characterization of Nanoparticle-Protein Corona Complexes

Understanding the biomolecular corona (PC) that forms around nanoparticles in biological fluids is crucial, as it directly influences cellular uptake, toxicity, and biodistribution—key factors in scaling up for in vivo applications [23].

Methodology:

- In Vitro Corona Formation: Incubate nanoparticles with relevant biological fluid (e.g., cell culture medium with fetal bovine serum, simulated lung fluid, or simulated intestinal fluid) under conditions that mimic the intended exposure route (e.g., temperature, pH, static/dynamic exposure) [23].

- Isolation of Hard Corona (HC): Separate the NP-HC complexes from unbound proteins and the biological fluid. For magnetic nanoparticles, use magnetic separation. For other types, centrifugation or filtration is employed [23].

- Physico-Chemical Characterization: Analyze the NP-HC complexes using techniques like Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) for hydrodynamic size and Zeta Potential, and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for morphology [23].

- Proteomics and Glycan Analysis: Digest the proteins associated with the corona and identify them using Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Glycan profiling can also be performed on the corona components [23].

Protocol 2: Recovery from Isopropanol Addition Error in TRIzol-Based RNA Isolation

A common laboratory error during scale-up can be the inadvertent use of isopropanol instead of chloroform after homogenization. The following protocol can help recover the sample [22].

Methodology:

- Add more isopropanol to the sample so that the total volume of isopropanol equals the volume of TRIzol Reagent originally used.

- Centrifuge the mixture at 7,500 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C to pellet the nucleic acids.

- Pour off the supernatant. Allow the pellet to air-dry slightly to reduce isopropanol volume, but do not let it dry completely.

- Resuspend the pellet in at least 15-20 volumes of TRIzol Reagent (e.g., for a 100 µL pellet, use 1.5-2 mL TRIzol). Break the pellet up thoroughly, potentially using a hand-held homogenizer.

- Store the solution for 10-15 minutes at room temperature, shaking by hand periodically to ensure it is well-dispersed.

- Proceed with the standard TRIzol protocol from the chloroform addition step. Note that RNA yields will be compromised, but a product may be obtainable for downstream applications like RT-PCR [22].

Workflow Visualization

Sterile Filtration and Aseptic Process Workflow

Nanoparticle-Protein Corona Characterization Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for RNA Isolation and Sterility Control

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Consideration for Scale-Up | | :--- | | :--- | | TRIzol Reagent | A monophasic solution of phenol and guanidine isothiocyanate for the simultaneous isolation of RNA, DNA, and proteins from cells and tissues [22]. | Handling large volumes of toxic phenol requires appropriate engineering controls and waste management procedures. | | DNase I (Amplification Grade) | An enzyme that degrades trace DNA contaminants to prevent false-positive results in downstream RNA applications like RT-PCR [22]. | Requires optimization of concentration, incubation time, and mixing for uniform treatment in large-volume batches. | | Glycogen | A co-precipitant used as a carrier to improve the yield and visualization of pellets when precipitating microgram or nanogram quantities of nucleic acids [22]. | Ensures consistent recovery of low-abundance nucleic acids during large-scale precipitations. | | RNase Inhibitors | Proteins that non-competitively bind RNases to protect RNA samples from degradation during processing and storage [22]. | Critical for maintaining RNA integrity during longer processing times inherent to scale-up. | | 0.2 µm Pore Size Membrane Filters | Sterilizing-grade filters used for the aseptic removal of bacteria from heat-sensitive liquid formulations [21] [20]. | Compatibility with nanoparticle formulation is key. Filter fouling and capacity must be tested at pilot scale. | | High-Salt Precipitation Solution | A solution of 0.8 M sodium citrate and 1.2 M NaCl used with isopropanol to precipitate RNA while keeping contaminating proteoglycans and polysaccharides soluble [22]. | Standardized preparation is necessary for consistent performance and compliance with Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). |

Supply Chain and Raw Material Sourcing for High-Quality Lipids and Polymers

The global market for advanced lipids and polymers is experiencing significant growth, driven by their critical role in nanomedicine, particularly in drug delivery systems for mRNA vaccines and gene therapies. Sourcing high-quality materials is foundational to scaling up nanoparticle production successfully.

Lipid Nanoparticles Market Dynamics

The Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) market is projected for strong growth, influenced by their adoption in drug delivery systems [24].

- Table: Global Lipid Nanoparticles Market Outlook

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Market Value (2024) | ~USD 2.5 Billion |

| Projected Market Value (2034) | ~USD 2.5 Billion (CAGR of 15-18%) |

| Primary Growth Driver | Application in mRNA vaccines & gene therapies |

Key market dynamics include [24]:

- Drivers: Rising demand for targeted drug delivery systems, the burden of chronic diseases, and the growth of personalized medicine.

- Restraints: High production costs, complex manufacturing processes, and stringent regulatory requirements.

- Opportunities: Innovations in green nanotechnology, sustainable production methods, and expansion in emerging markets.

Polymer Supply Chain Dynamics

The European polymer supply chain convenes to explore global market trends, sourcing strategies, and the impact of new regulations and digital technologies [25]. Key trends include a shift towards bio-based polymers like Polylactic Acid (PLA) for sustainability, though this sector can be affected by shifting political and regulatory landscapes [26].

Troubleshooting Common Sourcing and Quality Issues

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our nanoparticle batches show high variability in performance, but our raw material certificates indicate consistent quality. What could be wrong? A: Certificates of Analysis (CoA) for bulk materials may not capture the critical nanoscale properties that dictate performance. A common pitfall is relying solely on manufacturer specifications for materials like commercial lipids or polymers without independent verification. One study found significant discrepancies between the stated and actual sizes of commercially acquired silver nanoparticles [27]. Solution: Implement rigorous in-house physicochemical characterization (PCC) of all incoming raw materials under biologically relevant conditions.

Q2: Our nano-formulations are consistently failing endotoxin limits as we scale up. How can we control this? A: Endotoxin contamination is a frequent and serious issue; over one-third of samples submitted to a characterization lab required purification due to high endotoxin levels [27]. Contamination can originate from non-sterile reagents, equipment, or water. Solution: Adopt strict aseptic techniques throughout synthesis, use LAL-grade/pyrogen-free water, screen commercial starting materials for endotoxin, and depyrogenate all glassware [27].

Q3: How can we improve batch-to-batch consistency in nanoparticle synthesis during scale-up? A: Traditional batch reactors are prone to local variations in temperature and concentration, leading to inconsistent products [28]. Solution: Transition from batch to continuous flow synthesis methods, such as microreactors. These systems offer intensified mixing, narrower residence time distributions, and superior control over temperature and heating rates, resulting in nanoparticles with narrower size distributions and higher reproducibility [28].

Q4: What are the key physicochemical parameters to specify when sourcing lipids or polymers for nanomedicine? A: While composition is important, performance is often tied to nanoscale properties beyond bulk material specifications [29]. Solution: Your sourcing criteria should include:

- Size and Size Distribution: Significantly impacts biodistribution and cellular uptake.

- Charge (Zeta Potential): Influences colloidal stability and interaction with biological membranes.

- Purity and Stability: Ensure batch-to-batch consistency and shelf-life.

- Functional Performance: Specify performance-based metrics relevant to your application, as "same" material from different batches can behave differently [29] [27].

Experimental Protocols for Quality Assurance

Protocol 1: Endotoxin Testing with Interference Controls

Nanoparticles can often interfere with standard endotoxin tests, leading to false positives or negatives [27]. This protocol ensures accurate results.

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the nanoparticle sample in endotoxin-free water.

- Inhibition/Enhancement Control (IEC): This is a critical step. Spike one aliquot of the sample with a known amount of endotoxin standard. This controls for the possibility that the nanoparticle formulation is masking (inhibiting) or amplifying (enhancing) the assay signal.

- Assay Selection: Run the Limulus Amoebocyte Lysate (LAL) assay. If the nanoparticles are colored, avoid the chromogenic assay; if they are turbid, avoid the turbidity assay. Using two different LAL formats is recommended for cross-verification [27].

- Analysis: If the recovery of the spiked endotoxin in the IEC is outside the specified range (typically 50-200%), there is interference, and the assay method must be re-evaluated.

Protocol 2: Characterizing Raw Material Purity and Size

Do not trust manufacturer specifications at face value [27]. This protocol verifies key parameters of sourced materials.

- Sample Dispersion: Disperse the material (e.g., a lipid or polymer) in a solvent that mimics the final application medium (e.g., buffer at physiological pH).

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Measure the hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI) to assess size distribution and aggregation state. Note: DLS measures the size of the solvated particle, which can differ from dry state measurements.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Use TEM to visualize the primary particle size, shape, and morphology. This provides a direct measurement that complements DLS.

- Zeta Potential Measurement: Determine the surface charge of the particles in the dispersing medium. This is a key indicator of colloidal stability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Sourcing the right materials is critical for successful experimentation and scale-up.

- Table: Key Materials for Lipid and Polymer Nanoparticle Research

| Material / Reagent | Function in Research & Development |

|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | A core component of LNPs; enables encapsulation and endosomal release of nucleic acids (e.g., mRNA) [24]. |

| PEGylated Lipids | Used to modify nanoparticle surface, reducing opsonization and improving circulation time; can help control immunogenicity [24]. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | A common stabilizing agent in metal nanoparticle synthesis; controls growth and prevents aggregation [28]. |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | A biodegradable, bio-based polymer used for controlled-release drug delivery and sustainable material solutions [26]. |

| Oleic Acid / Oleylamine | Common stabilizing agents used in nonpolar solvents to control nanoparticle growth and provide colloidal stability [28]. |

| Limulus Amoebocyte Lysate (LAL) | A critical reagent for detecting and quantifying bacterial endotoxin contamination in nano-formulations [27]. |

Workflow Visualization: From Sourcing to Quality Assurance

The following diagram illustrates the integrated process of sourcing raw materials and establishing quality control for scalable nanoparticle production.

Figure 1. Integrated workflow for sourcing and quality assurance in nanoparticle production. This process emphasizes the critical feedback loop where raw materials that fail quality control trigger a re-evaluation of the supplier or material batch.

Advanced Manufacturing: Microreactor Synthesis Workflow

To address common challenges of batch-to-batch consistency and reactor clogging during scale-up, consider adopting continuous flow synthesis.

Figure 2. Biphasic microreactor setup for nanoparticle production. This system uses an inert carrier fluid to create segmented slugs of the reaction mixture, which intensifies mixing, prevents reactor fouling, and ensures a narrow residence time distribution for highly uniform nanoparticles [28].

Scalable Production Technologies: From Microfluidics to Supercritical Fluids

Core Principles of High-Flow Microfluidics

What are the fundamental principles governing high-flow microfluidics?

High-flow microfluidic systems manipulate fluids in sub-millimeter channels, where laminar flow dominates fluid behavior. In this regime, fluids move in parallel layers without turbulence, enabling precise control over reactions and interactions. The key to scaling up production while maintaining control lies in leveraging chaotic advection through specific micromixer geometries, such as staggered herringbone mixers, which create micro-vortices to enhance mixing efficiency without relying on turbulence [30] [31].

Optimization of Flow Parameters

How do Total Flow Rate (TFR) and Flow Rate Ratio (FRR) affect nanoparticle synthesis?

Optimizing TFR and FRR is critical for controlling the size and dispersity of nanoparticles during synthesis. These parameters directly influence the mixing efficiency, which governs the kinetics of nanoparticle nucleation and growth.

Table 1: Effect of Microfluidic Flow Parameters on PLGA Nanoparticle Characteristics [31]

| Total Flow Rate (TFR) | Flow Rate Ratio (FRR) - Aqueous:Organic | Average Nanoparticle Size | Polydispersity Index (PDI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower TFR | 3:1 | Larger size | Broader distribution |

| Higher TFR | 3:1 | Smaller size | Narrower distribution |

| System-dependent optimum | 1:1 | Smaller size (~130 nm) | Low (~0.15) |

| System-dependent optimum | 5:1 | Larger size (~160 nm) | Low (~0.16) |

What is a detailed experimental protocol for optimizing TFR and FRR?

Objective: To systematically determine the optimal TFR and FRR for synthesizing poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles with a target size of 200 nm and a low Polydispersity Index (PDI < 0.2) [31].

Materials:

- Organic Phase: PLGA polymer dissolved in a water-miscible solvent like acetonitrile (ACN).

- Aqueous Phase: Surfactant solution, such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) in deionized water.

- Equipment: Syringe pumps, a microfluidic chip (e.g., with a staggered herringbone or three-inlet mixer), and a dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument for nanoparticle characterization.

Methodology:

- Fix the FRR: Begin with an FRR (Aqueous:Organic) of 3:1.

- Vary the TFR: Synthesize nanoparticles at different TFRs (e.g., 2 mL/min, 4 mL/min, 8 mL/min, 12 mL/min) while keeping the FRR constant.

- Characterize Output: Measure the size and PDI of the resulting nanoparticles for each condition using DLS.

- Fix the Optimal TFR: Once the TFR that produces the smallest size and PDI is identified, keep this value constant.

- Vary the FRR: Synthesize a new set of nanoparticles at different FRRs (e.g., 1:1, 3:1, 5:1, 10:1) using the optimal TFR.

- Final Characterization: Measure the size and PDI for each FRR condition to determine the overall optimal parameters.

This iterative process maps the design space and identifies the combination that yields the most desirable nanoparticle properties.

Scale-Up Through Parallelization

What strategies exist for scaling up microfluidic production, and how do they compare?

Moving from lab-scale synthesis to clinically relevant volumes requires moving beyond increasing the flow rate in a single channel, which can lead to detrimental backpressure. The most effective strategy is parallelization.

Table 2: Comparison of Microfluidic Scale-Up Strategies for Nanoparticle Production [30]

| Scale-Up Strategy | Description | Key Advantage | Reported Scale-Up Factor | Inherent Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Channel High-Flow | Increasing flow rate and reagent concentration in a single mixer. | Simplicity of setup. | Limited | Increased backpressure can affect device integrity and mixing performance. |

| Numbered Parallelization | Using a device with multiple identical mixing channels operating simultaneously. | Maintains identical product quality across all channels. | 10x to 256x | Requires careful design of flow resistors for even distribution. |

| Concentration & Parallelization | Combining parallelized chips with increased reagent concentration. | Massive multiplicative increase in output. | 5,100x (reported) | Potential for fouling or blockages at higher concentrations. |

Can you provide a protocol for scaling up via a parallelized microfluidic device?

Objective: To scale up the production of ultrasmall silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag₂S-NP) using a Scalable Silicon Microfluidic System (SSMS) with parallelized channels [30].

Materials:

- Reagents: Silver nitrate (AgNO₃), sodium sulfide (Na₂S), L-glutathione (GSH), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), deionized water.

- Equipment: Scalable Silicon Microfluidic System (e.g., with 1, 10, or 256 parallel channels), pressure-driven flow system, UV-visible spectrophotometer, DLS.

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation:

- Solution A (GSH + AgNO₃): Dissolve 767 mg GSH and 42.5 mg AgNO₃ in 75 mL deionized water. Adjust pH to 7.4 using NaOH.

- Solution B (Na₂S): Dissolve 10 mg Na₂S in 25 mL deionized water.

- System Priming: Load the solutions into pressurized vessels connected to the SSMS chip. Ensure the chip is housed in its aluminum fixture.

- Flow Rate Calibration: Set the pressure controllers to achieve a 3:1 flow rate ratio (Solution A : Solution B) with a target total flow rate of up to 2 mL/min per channel. For a 256-channel SSMS, this can achieve a total flow rate of 17 L/hour.

- Nanoparticle Synthesis: Initiate flow. The reagents mix in the parallelized staggered herringbone channels, resulting in the instantaneous formation of Ag₂S-NP.

- Product Collection: Collect the effluent containing the synthesized nanoparticles from the single output port.

- Quality Control: Characterize the nanoparticles from each run using UV-visible spectrometry and DLS to ensure consistency with small-scale batches in terms of core size, concentration, and optical properties.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

What are typical failure modes in microfluidics and their solutions?

Table 3: Microfluidics Troubleshooting Guide for Common Failure Modes [32]

| Failure Category | Specific Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical | Channel blockages | Particle accumulation, air bubbles, precipitate formation [32] [31]. | Pre-filter all reagents, implement degassing steps, ensure chemical compatibility. |

| Leakage | Poor alignment of components, inadequate sealing, material deformation [32]. | Perform careful design iterations, select materials with appropriate structural integrity. | |

| Fluidic & Performance | Inconsistent nanoparticle size | Fluctuations in TFR/FRR, inefficient mixing, temperature gradients [32] [31]. | Use high-precision syringe or pressure pumps, employ chaotic mixers (herringbone), control ambient temperature. |

| Low production yield | Single-channel throughput limits, low reagent concentration [30]. | Move to a parallelized microfluidic device and/or optimize reagent concentrations for scale-up. | |

| Electrical | Pump failure | Inconsistent voltage, battery fatigue, faulty connections [32]. | Use regulated power supplies, implement routine maintenance checks, properly encapsulate electronics. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is a three-inlet microfluidic junction sometimes superior to a standard Y-junction?

A: A three-inlet geometry, where the organic phase flows through a central channel flanked by two aqueous streams, provides a more focused and rapid mixing interface. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations confirm that this design creates significantly more homogeneous mixing and efficient interfacial contact, leading to smaller, more uniform nanoparticles with superior post-lyophilization stability compared to a simple Y-junction [31].

Q2: What are the key material compatibility considerations for microfluidic devices?

A: Material selection is critical to prevent chemical failures. The device material must be structurally sound to withstand operational pressures and chemically compatible with all reagents and solvents used. Incompatibility can lead to channel degradation, reagent breakdown, or the formation of solid precipitates that cause blockages [32].

Q3: How can I confirm that my scaled-up process maintains product quality?

A: Consistent product quality during scale-up must be verified through rigorous characterization. As demonstrated in Ag₂S-NP synthesis, this includes comparing key metrics such as core size (via TEM/DLS), concentration, UV-visible absorption spectra, and in vitro contrast generation between small-scale and large-scale batches. Furthermore, in vivo performance, such as imaging contrast and biodistribution/clearance profiles, should be consistent [30].

Q4: Our parallelized device has inconsistent output between channels. What could be wrong?

A: Inconsistent output typically stems from uneven flow distribution. Advanced parallelized systems like the SSMS incorporate flow resistors within each channel to ensure equal flow rates. If your custom system lacks this, flow may be uneven. Check for blockages in individual channels and ensure your input pressure is sufficient and stable to drive flow uniformly through all parallel paths [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Materials and Reagents for Microfluidic Nanoparticle Synthesis

| Item | Function / Role | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Staggered Herringbone Micromixer (SHM) | Induces chaotic advection for rapid and uniform mixing, crucial for monodisperse nanoparticle formation. | Used for scalable synthesis of Ag₂S-NP [30] and PLGA nanoparticles [31]. |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | A biocompatible, biodegradable polymer used as the matrix for drug-loaded nanoparticles. | Optimized for nanoprecipitation in microfluidics to control size and PDI [31]. |

| L-Glutathione (GSH) | Serves as a coating or capping agent for metal-based nanoparticles, providing stability and biocompatibility. | Used in the aqueous-phase synthesis of ultrasmall silver sulfide (Ag₂S) nanoparticles [30]. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | A surfactant that stabilizes nanoparticles during and after formation, preventing aggregation. | Used in the aqueous phase during PLGA nanoprecipitation [31]. |

| Scalable Silicon Microfluidic System (SSMS) | A platform with parallelized mixing channels (e.g., 256x) for high-throughput production without sacrificing quality. | Enabled a 5,100-fold increase in Ag₂S-NP output [30]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Pressure-Related Issues

Problem: Unexpectedly High System Pressure A sudden or consistent increase in system pressure can indicate a blockage or other flow restriction, risking damage to column packing or equipment.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Blocked tubing or nozzle | Check pressure step-by-step. Disconnect components starting from the post-column end while the system is at operational flow rate. Observe for a significant pressure drop. | Replace any blocked tubing or nozzle. Do not attempt to re-use them. [33] |

| Blocked pre-column or column frits | Identify if the pressure issue is isolated to the column set by checking the system pressure without columns installed. | Replace the pre-column if it is the cause. For analytical columns, consult the user documentation for approved cleaning procedures or frit replacement. [33] |

| Particle Aggregation in Nozzle | Inspect the exit nozzle for visible blockages post-run. | Implement a controlled, two-step gradient pressure reduction to prevent Mach disk formation and subsequent particle coagulation and growth. [34] |

Problem: Pressure Fluctuations During Scale-Up When moving from laboratory to pilot scale, maintaining consistent pressure profiles is critical for reproducing particle characteristics.

| Scale-Up Challenge | Consideration | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Maintaining Extraction Efficiency | Scaling the process while preserving the supercritical fluid's solvent power and mass transfer properties. | Adopt a scale-up criterion of maintaining the solvent mass to feed mass ratio constant. This has been successfully used for a 15-fold scale-up of supercritical fluid extraction. [35] |

Particle Characteristics Issues

Problem: Broad Particle Size Distribution (PSD) Achieving a narrow PSD is a key advantage of SCF processes, and its loss indicates a process imbalance.

| Possible Cause | Underlying Principle | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled Particle Growth | Rapid, uncontrolled nucleation followed by particle growth via condensation and coagulation. | Utilize the Controlled Expansion of Supercritical Solution (CESS) method. This involves a specific pressure reduction profile to control mass transfer and particle growth, preventing Mach disk formation. [34] |

| Agglomeration of Particles | Insufficient stabilization of particles after formation. | Use a surfactant in the water phase to avoid agglomeration. The particles remain stabilized by the surfactant and can stay stable over extended storage periods. [36] |

| Wide Residence Time Distribution | Variations in the time fluid elements spend in the system lead to uneven particle growth. | Consider microfluidic reactors. The small length scale of microfluidics results in a narrower residence time distribution (RTD), allowing for superior control over nanoparticle size distribution. [37] |

Problem: Low Product Yield or Encapsulation Efficiency

| Possible Cause | Impact on Yield | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient Organic Solvent Removal | In processes like Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Emulsions (SFEE), incomplete solvent removal affects product purity and process economics. | Integrate a solvent recovery system (e.g., a distillation column) to separate and recycle the organic solvent and CO₂. This ensures the aqueous raffinate is solvent-free and improves viability. [36] |

| Suboptimal ScCO₂ Interaction with Emulsion | Poor contact between scCO₂ and the emulsion leads to incomplete extraction of the organic phase. | Use a counter-current packed column. This configuration enhances mass transfer between the emulsion and scCO₂, leading to high production capacity, product homogeneity, and recovery. [36] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What makes Supercritical Fluid Technology a "green" alternative for nanoparticle production? SCF technology, particularly when using supercritical CO₂ (scCO₂), is considered environmentally friendly because scCO₂ is non-toxic, non-flammable, and abundant. It serves as a replacement for hazardous organic solvents. Furthermore, the CO₂ used in the process can be almost entirely recovered and recycled within the system, minimizing environmental impact. The final product is also typically free of residual organic solvents. [36] [37] [38]

Q2: How can I control the size and distribution of nanoparticles produced via SCF processes? Control is achieved through several key parameters:

- Controlled Expansion: Using methods like CESS with a specific pressure reduction profile to manage nucleation and particle growth. [34]

- Emulsion Template: In SFEE, the initial size of the emulsion droplets directly influences the final particle size. Modifying the emulsion formulation allows for precise size adjustment. [36]

- Microfluidic Reactors: These systems offer precise fluid manipulation, leading to the production of uniform nanoparticles with a narrow size distribution due to a narrower residence time distribution. [37]

- Stabilizers: Employing surfactants prevents agglomeration, maintaining a narrow size distribution post-precipitation. [36]

Q3: Our research is promising at the lab scale. What is the key to scaling up SCF processes for industrial nanoparticle production? Successful scale-up requires integrated process design. A critical study shows that maintaining a constant solvent mass to feed mass ratio is an effective criterion for scaling supercritical fluid extraction. Furthermore, for commercial viability, the process must integrate solvent recovery and recycling systems. Process simulation tools like Aspen Plus can be used to model and design these integrated systems at different scales. [36] [35]

Q4: What are the primary SCF techniques for producing lipid nanoparticles like liposomes, and what are their advantages? Several supercritical methods have been developed to overcome the limitations of conventional multi-step, solvent-heavy liposome production. Key techniques include:

- Supercritical Liposome Method: Uses scCO₂ to dissolve lipids, significantly reducing organic solvent use (up to 15 times less). [38]

- RESS Modified: Involves dissolving lipids in a scCO₂/ethanol mixture and expanding it into an aqueous solution, achieving high encapsulation efficiency (e.g., >80%). [38]

- DESAM (Depressurization of an Expanded Solution into Aqueous Media): A fast, simple process operating at mild pressures (<6 MPa) that produces liposomes with very low residual solvent concentration (<4% v/v). [38] These methods generally yield particles with narrower size distributions and greater physical stability compared to those produced by classical methods. [38]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Controlled Expansion of Supercritical Solution (CESS) for Drug Nanoparticles

This protocol details the production of pure drug nanoparticles with a narrow size distribution, based on the CESS method. [34]

1. Principle The CESS method is based on the controlled expansion of a supercritical solution saturated with a solute. A specific, graded pressure reduction profile is applied to control mass transfer and nucleation, preventing uncontrolled particle growth via condensation and coagulation. This ensures the production of stable, monodisperse nanoparticles. [34]

2. Materials and Equipment

- Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API): e.g., Piroxicam.

- Solvent: High-purity Carbon Dioxide (CO₂).

- High-Pressure Vessel: Equipped with heating and pressure control.

- Syringe Pump or Compressor: For CO₂ pressurization.

- Heated Nozzle: For controlled expansion.

- Particle Collection Chamber: Cooled with dry ice.

- Back Pressure Regulator: For precise pressure control.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure 1. Loading: Place the pure drug (e.g., Piroxicam) into the high-pressure vessel. 2. Pressurization & Heating: Pressurize the system with CO₂ and heat it above the critical point (TC = 31.1 °C, PC = 7.4 MPa) to create a supercritical state. Allow time for the drug to dissolve in the scCO₂. 3. Controlled Expansion: Pump the supercritical solution through a heated nozzle. Critical Step: Reduce the pressure according to a two-step gradient profile to prevent Mach disk formation and particle coagulation. 4. Particle Collection: The precipitated nanoparticles are collected in a chamber cooled with dry ice. 5. CO₂ Venting: The CO₂ is vented as a gas, leaving behind solvent-free nanoparticles.

4. Expected Output

- Product: Piroxicam nanoparticles.

- Production Rate: ~60 mg/h.

- Particle Size: 176 ± 53 nm (narrow size distribution). [34]

Protocol: Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Emulsions (SFEE) for Encapsulation

This protocol describes the encapsulation of a bioactive compound (e.g., Astaxanthin) in a polymer using a counter-current packed column. [36]

1. Principle An oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion is created, containing the bioactive compound and a coating polymer dissolved in the organic phase. This emulsion is then contacted with scCO₂ in a counter-current packed column. The scCO₂ rapidly extracts the organic solvent, causing the compound and polymer to precipitate as core-shell particles suspended in the water phase, which is stabilized by a surfactant. [36]

2. Materials and Equipment

- Bioactive Compound: e.g., Astaxanthin.

- Coating Polymer: e.g., Ethyl Cellulose.

- Organic Solvent: e.g., Ethyl Acetate.

- Aqueous Phase: Water with a suitable surfactant (e.g., Tween 80).

- Emulsification Equipment: High-shear mixer or homogenizer.

- Packed Column: Stainless-steel, packed with high-surface-area material.

- Pumps: For emulsion and scCO₂ delivery.

- scCO₂ System: Including pump, heater, and back-pressure regulator.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure 1. Emulsion Preparation: Dissolve the bioactive compound and polymer in the organic solvent (e.g., Ethyl Acetate). Create an O/W emulsion by mixing this organic phase with an aqueous surfactant solution at a set ratio (e.g., 20/80 organic/water). Homogenize to achieve a fine emulsion. 2. Column Operation: * Feed the emulsion from the top of the packed column. * Feed scCO₂ from the bottom of the column, creating a counter-current flow. * Maintain moderate operating conditions (e.g., 8–10 MPa, 37–40 °C). * Control the Liquid to Gas (L/G) ratio (e.g., 0.1). 3. Separation and Collection: * The scCO₂, now containing the extracted organic solvent, exits the top and is sent to a recovery system. * The aqueous raffinate, containing the suspended nanoparticles, exits the bottom of the column.

4. Expected Output

- Product: Astaxanthin encapsulated in ethyl cellulose particles.

- Particle Size: ~360 nm mean diameter.

- Encapsulation Efficiency: ~85%.

- Polymer Recovery: ~90%. [36]

Integrated SFEE Process with Solvent Recycling

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of a scaled-up SFEE process, integrating solvent recovery for environmental and economic sustainability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and their functions in SCF processes for nanoparticle production.

| Item | Function & Application | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| Supercritical CO₂ | The primary solvent in SCF processes. Its tunable density and solvent power, low toxicity, and ease of removal make it ideal for extractions and precipitations. [36] [37] | Used as a universal solvent in CESS for pure drug nanoparticle production and as the extracting fluid in SFEE. [34] [36] |

| Ethyl Acetate | A common organic solvent for the oil phase in emulsions. It is used to dissolve lipids, polymers, and bioactive compounds. [36] | Serves as the organic phase in SFEE to dissolve astaxanthin and ethyl cellulose. It is subsequently extracted by scCO₂. [36] |

| Phospholipids (e.g., Phosphatidylcholine) | The primary building blocks for lipid-based drug delivery systems such as liposomes. They form the bilayer structure that encapsulates active ingredients. [38] | Dissolved in scCO₂/ethanol mixtures in modified RESS or DESAM processes to form liposomes encapsulating compounds like puerarin or essential oils. [38] |

| Surfactants (e.g., Polysorbates) | Stabilize emulsions during formation and prevent aggregation of nanoparticles post-precipitation by providing a steric or electrostatic barrier. [36] | Added to the continuous water phase in SFEE to stabilize the initial emulsion and the final nanoparticle suspension, ensuring long-term stability. [36] |

| Ethanol (as Co-solvent) | A polar co-solvent added to scCO₂ to enhance its solvent power for more polar compounds that are poorly soluble in pure scCO₂. [37] [38] | Used in a mixture with scCO₂ to dissolve phospholipids effectively for liposome production via the supercritical liposome method. [38] |

Within the strategic objective of scaling up nanoparticle production for pharmaceutical applications, membrane-based techniques offer a promising pathway due to their scalability, precise control, and potential for continuous operation. Membrane processes present a viable alternative to conventional bottom-up and top-down nanoparticle synthesis methods, which often face challenges in controlling particle size distribution and achieving industrial-scale throughput [39]. This technical resource focuses on two key membrane-assisted methods: membrane contactors for nanoprecipitation and self-assembly, and membrane extrusion for post-formation size reduction and homogenization. These techniques are particularly advantageous for the production of drug-loaded nanocarriers such as liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and solid lipid nanoparticles, as they can enhance drug bioavailability, improve solubility, and fine-tune release profiles [39] [40]. The following sections provide a detailed troubleshooting guide and FAQs to support researchers in optimizing these processes for robust and reproducible nanoparticle formation.

Membrane Contactor Operation & Troubleshooting

Membrane contactors are hybrid systems that use a porous membrane to facilitate mass transfer and reaction between two phases, leading to the formation of nano-sized entities through mechanisms like dispersion, emulsion, or interfacial self-assembly [39] [41]. The membrane acts as a stabilized, constant-area interface, and the process driving force is a difference in chemical potential, not pressure-driven flux [39] [41].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary modes of operation for a membrane contactor in nanoparticle synthesis? A1: Membrane contactors typically operate in three main modes [39]:

- Dispersion Mode: A membrane (typically MF or UF) is used to inject one precursor as uniform droplets into a bulk continuous phase, where they react to form nanoparticles.

- Emulsion Mode: The droplet permeating through the membrane becomes the final nanoparticle, often through crystallization or phase separation.

- Contactor/Self-assembly Mode: The membrane acts as a phase contactor with a reaction occurring at or near the membrane surface, ideally through diffusive mass transfer alone.

Q2: How do I select the appropriate membrane type and material? A2: The selection is critical and depends on your application:

- Material Compatibility: Inexpensive microporous polypropylene (PP) or polyethersulfone (PES) membranes are common for contactor-driven nanoparticle synthesis [39]. The membrane must be chemically resistant to your process fluids.

- Hydrophobicity/Hydrophilicity: The membrane must not be wetted by the liquid phase it is in contact with. A hydrophobic membrane is used for aqueous phases, while a hydrophilic membrane can be used for organic phases [41].

- Pore Size: Pore sizes typically range from 10 nm to 10 μm [39]. A larger pore size reduces mass transfer resistance but also lowers the breakthrough pressure (the pressure at which the fluid will wet the pores), as defined by the Laplace equation:

ΔP = 4σ cosθ / d_p, whereσis surface tension,θis the contact angle, andd_pis the pore diameter [41].

Q3: What is the consequence of operating outside the recommended flow rates? A3: Operating below the minimum recommended flow rate can lead to channeling, where the fluid finds a path of least resistance and does not flood the entire shell volume of a hollow fiber module. This reduces the effective surface area for mass transfer and results in lower-than-expected performance [42]. This can be partially mitigated by orienting the contactor vertically with upward flow, but staying within the manufacturer's guidelines is strongly advised.

Q4: Can I operate a membrane contactor at elevated temperatures? A4: Continuous operation at high temperatures is not recommended. It can accelerate membrane oxidation, reduce service life, and generate excessive water vapor that can condense and block vacuum lines [42]. If high temperatures are necessary, you may require a larger vacuum pump and higher sweep gas rates.

Troubleshooting Guide for Membrane Contactors

The table below outlines common failure modes, their symptoms, causes, and corrective actions.

| Failure Mode | Symptoms | Potential Causes | Corrective & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced Degassing/ Reaction Efficiency [42] [43] | Slow nanoparticle formation, wide particle size distribution. | Channeling (flow too low), membrane wetting, fouling, insufficient vacuum/sweep gas. | Ensure flow rate is within specified range; check vacuum pump performance and for leaks; verify sweep gas purity and flow rate [42]. |

| Membrane Wetting [43] [41] | Catastrophic failure; sudden, permanent drop in performance; two phases mix. | Transmembrane pressure exceeding breakthrough pressure; presence of surfactants reducing surface tension. | Always maintain liquid pressure below the breakthrough pressure; carefully select chemicals and pre-treat feed to avoid surfactants [41]. |

| High Temperature Damage [43] | Irreversible membrane damage, often localized to the first module in a series. | Feed temperature exceeding membrane's maximum rated temperature. | Install and maintain reliable temperature controls and safety interlocks on the feed pre-heater [43]. |

| Freezing Damage [43] | Irreversible physical damage to the membrane. | Exposure to sub-zero temperatures without antifreeze measures during shutdown. | Implement proper system drainage or use antifreeze solutions during planned shutdowns or in cold environments [43]. |

| Organic Fouling/ Scaling [44] [45] | Gradual decline in flux and efficiency; increased pressure drop. | Precipitation of inorganic salts (e.g., gypsum) or deposition of organic matter on the membrane surface. | Pre-treat feed water to remove foulants; optimize cleaning-in-place (CIP) procedures with chemical suppliers [45]. |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

For degassing applications, which can be analogous to creating a driving force for nanoprecipitation, performance follows predictable relationships. The table below summarizes key parameters based on modeling and experimental data [46].

| Parameter | Impact on Mass Transfer Efficiency | Typical Values & Relationships |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Flow Rate to Membrane Area Ratio (Q/A) | Primary determinant of efficiency. Lower ratio yields higher efficiency [46]. | For O₂ removal with 140 µm fibers, 98% efficiency requires Q/A ≈ 1.4x10⁻⁵ m³L s⁻¹ m⁻²M,int [46]. |

| Fiber Diameter | Smaller diameter increases degassing efficiency but also pressure drop [46]. | A fiber length of 0.12 m for 140 µm fibers yields a ~0.1 bar pressure drop [46]. |

| Operating Mode | Affects the maximum achievable removal. | "Combo mode" (Vacuum + N₂ sweep) is most efficient for O₂ removal. For CO₂, a filtered air sweep is often sufficient [42]. |

Membrane Extrusion & Troubleshooting

Membrane extrusion is a post-formation process used to reduce the size and achieve a narrow size distribution of pre-formed lipid or polymeric nanoparticles (e.g., liposomes) by forcing them through a porous membrane under pressure [39].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the main purpose of extrusion in nanoparticle production? A1: The primary goal is to produce a population of nanoparticles with a uniform, defined size. This is critical for ensuring batch-to-batch reproducibility, predictable drug release profiles, and successful scale-up [39] [40].