Printable Nanoparticles for Wearable Biosensors: A New Era in Mass-Produced Personalized Health Monitoring

This article explores the groundbreaking convergence of inkjet printing and nanotechnology for the mass production of wearable biosensors.

Printable Nanoparticles for Wearable Biosensors: A New Era in Mass-Produced Personalized Health Monitoring

Abstract

This article explores the groundbreaking convergence of inkjet printing and nanotechnology for the mass production of wearable biosensors. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it delves into the foundational science of core-shell nanoparticles, detailed methodologies for their fabrication and printing, and critical optimization strategies to overcome manufacturing challenges. Further, it provides a rigorous validation of this technology against current standards, highlighting its transformative potential for real-time, non-invasive monitoring of biomarkers in chronic disease management, drug level tracking, and personalized medicine.

The Building Blocks: Core-Shell Nanoparticles and Biosensor Fundamentals

The integration of nanomaterials into biosensing platforms has marked a revolutionary advance in diagnostic technology, particularly for the development of next-generation wearable devices [1]. These materials, typically ranging in size from 1 to 100 nanometers, exhibit unique physical and chemical properties that are harnessed to significantly enhance the sensitivity, stability, and specificity of biosensors [2]. Within the specific context of inkjet printing for wearable biosensors, nanomaterials provide the essential functional inks that enable the precise, scalable, and cost-effective fabrication of conductive and biorecognitive patterns directly onto flexible textile substrates [1] [3]. This document outlines the fundamental properties of key nanomaterials, their advantages in biosensing applications, and provides detailed experimental protocols for their formulation and implementation in wearable devices, framing this discussion within a broader research thesis on advanced manufacturing for health monitoring.

Fundamental Properties of Nanomaterials for Biosensing

The exceptional performance of nanomaterials in biosensing applications is derived from a set of intrinsic properties that become pronounced at the nanoscale. The table below summarizes these core properties and their direct impact on biosensor functionality.

Table 1: Core Properties of Nanomaterials and Their Impact on Biosensing.

| Property | Description | Impact on Biosensor Performance |

|---|---|---|

| High Surface-to-Volume Ratio | Provides a vastly increased surface area for the immobilization of biorecognition elements (enzymes, antibodies, aptamers) per unit mass [2]. | Enhances sensitivity by allowing a higher density of capture probes, leading to a stronger signal per binding event [2]. |

| Excellent Electrical Conductivity | Exhibited by materials like graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and metal nanoparticles (e.g., Au, Ag), facilitating efficient electron transfer [4] [5]. | Improves the speed and efficiency of electrochemical signal transduction, which is critical for real-time monitoring [4]. |

| Tailorable Surface Chemistry | Surfaces can be functionalized with various chemical groups (-COOH, -NH₂) to covalently attach biomolecules [2]. | Improves selectivity and stability of the biorecognition layer, reducing nonspecific binding and enhancing reproducibility [2]. |

| Plasmonic Properties | Noble metal nanoparticles (e.g., Au, Ag) exhibit localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), which alters their optical properties in response to the local environment [6]. | Enables highly sensitive optical detection methods, such as surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) and colorimetric sensing [6]. |

Key Nanomaterial Classes and Their Advantages

Different classes of nanomaterials offer distinct advantages, making them suitable for various roles in biosensor design, from signal transduction to providing a scaffold for biorecognition.

Metal-Based Nanoparticles

- Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) and Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs): These are among the most widely used nanomaterials due to their excellent biocompatibility, stability, and strong plasmonic effects. They serve as excellent platforms for SERS-based immunoassays, as demonstrated by Au-Ag nanostars used for the sensitive detection of the α-fetoprotein cancer biomarker [6]. Their surfaces are easily modified with thiol groups for robust bioconjugation.

- Liquid Metal Nanoparticles (LMPs): Materials like gallium-based alloys are gaining traction for stretchable electronics. They combine high conductivity with mechanical deformability. When formulated into composites, they enable the development of stretchable and conductive inks for wearable sensors that monitor physiological signals like EMG and ECG [4].

Carbon-Based Nanomaterials

- Graphene and Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO): These two-dimensional materials are prized for their extraordinary electrical conductivity, mechanical strength, and high surface area. They are often used as electrode modifiers in electrochemical sensors. For instance, a novel DyCoO3@rGO nanocomposite has shown high specific capacitance and stability for energy storage applications in electronics [3], while graphene foam electrodes have been used for sensitive tau protein detection [4].

- Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs): CNTs offer high electrical conductivity and a tubular structure that is beneficial for electron transfer and the immobilization of biomolecules, enhancing sensor sensitivity [2].

Polymer-Based Nanoparticles

- Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs): MIPs are synthetic polymers with tailor-made cavities that mimic natural antibody-antigen interactions. A key advancement is their use in core-shell nanoparticles, where a MIP shell (e.g., nickel hexacyanoferrate) provides specific molecular recognition, and a redox-active core (e.g., Prussian blue analog) enables electrochemical signal transduction. This approach is ideal for the mass production of selective wearable and implantable biosensors via inkjet printing [3].

Experimental Protocols: Inkjet Printing Nanomaterials for Wearable Biosensors

Protocol: Formulation of a Graphene-Based Conductive Ink

This protocol details the synthesis of a stable, water-based graphene oxide (GO) ink suitable for inkjet printing on textile substrates [1] [5].

- Objective: To formulate a conductive ink that maintains colloidal stability, prevents nozzle clogging, and yields highly conductive patterns upon printing and reduction.

- Materials:

- Graphene oxide powder

- Deionized (DI) water

- N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) or ethylene glycol (as a stabilizing co-solvent)

- Non-ionic surfactant (e.g., Triton X-100)

- Ultrasonic probe sonicator

- Magnetic stirrer and hotplate

- Vacuum filtration setup (0.22 µm membrane)

- Procedure:

- Dispersion: Disperse 20 mg of graphene oxide powder in 100 mL of a 4:1 (v/v) mixture of DI water and DMF.

- Exfoliation & Homogenization: Subject the mixture to probe sonication in an ice bath for 60 minutes at 500 W, with a 5-second on/2-second off pulse cycle to prevent overheating.

- Surfactant Addition: Add 0.1% (v/v) of non-ionic surfactant to the dispersion and stir magnetically for 12 hours at room temperature.

- Filtration & Characterization: Filter the resulting dispersion through a 0.22 µm membrane to remove any large aggregates. Characterize the ink for viscosity (target: 2-10 cP), surface tension (target: 28-35 mN/m), and particle size distribution (target: Z-Avg < 200 nm) prior to printing.

Protocol: Inkjet Printing and Post-Processing for Textile Electrodes

This protocol covers the printing and processing steps to create functional conductive patterns on a textile substrate [1] [5].

- Objective: To fabricate a durable, flexible, and highly conductive electrode pattern on a polyester/cotton blend fabric.

- Materials:

- Formulated graphene oxide ink

- Piezoelectric inkjet printer (e.g., Dimatix DMP-2831)

- Polyester/cotton blend fabric

- Ascorbic acid (0.1 M solution) or Hydriodic acid (HI) vapor

- Oven or hotplate

- Procedure:

- Substrate Pretreatment: Clean the textile substrate with isopropanol and DI water in an ultrasonic bath for 15 minutes. Dry completely and plasma treat for 2 minutes to increase surface hydrophilicity.

- Printer Setup: Load the ink into a cartridge. Use a 10 pL or 1 pL nozzle. Set the waveform parameters (voltage, pulse duration) as recommended by the printer manufacturer for the specific ink's properties.

- Printing: Print the desired electrode pattern (e.g., interdigitated electrode) onto the pretreated textile. Maintain a substrate temperature of 40°C during printing to facilitate controlled droplet drying. Perform 2-3 print passes to ensure continuity and adequate thickness.

- Post-Printing Reduction: To convert the insulating GO into conductive reduced GO (rGO), either:

- Chemical Reduction: Immerse the printed textile in a 0.1 M ascorbic acid solution at 80°C for 6 hours, or

- Vapor Reduction: Expose the printed textile to HI vapor at 40°C for 30 seconds.

- Curing & Washing: Rinse the reduced electrode thoroughly with DI water and ethanol. Thermally cure the electrode in an oven at 120°C for 15 minutes to enhance adhesion and stability. Test conductivity and mechanical durability under bending cycles (e.g., up to 1200 cycles) [3].

Protocol: Functionalization with a Biorecognition Element

This protocol describes the immobilization of an antibody onto a printed electrode for specific antigen detection [4] [2].

- Objective: To covalently immobilize monoclonal anti-α-fetoprotein antibodies (AFP-Ab) onto a COOH-functionalized printed graphene electrode.

- Materials:

- Printed and reduced graphene electrode

- 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) and N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)

- Monoclonal Anti-AFP antibody

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4)

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)

- Ethanolamine (1 M, pH 8.5)

- Procedure:

- Surface Activation: Prepare a fresh solution of 2 mM EDC and 5 mM NHS in MES buffer (pH 5.5). Incubate the printed electrode in this solution for 30 minutes at room temperature to activate the surface carboxyl groups, forming amine-reactive NHS esters.

- Antibody Coupling: Rinse the electrode with PBS (pH 7.4). Incubate the activated electrode in a solution containing 50 µg/mL of Anti-AFP antibody in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Quenching & Blocking: Rinse the electrode to remove unbound antibodies. Incubate the electrode in 1 M ethanolamine (pH 8.5) for 15 minutes to quench any remaining active esters. Then, incubate in a 1% (w/v) BSA solution in PBS for 1 hour to block non-specific binding sites.

- Storage: The functionalized biosensor can be stored in PBS at 4°C until use. Before testing, perform electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) in a ferri/ferrocyanide solution to confirm successful antibody immobilization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and reagents for developing nanomaterial-based inkjet-printed biosensors.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Nanomaterial Biosensor Fabrication.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene Oxide (GO) Dispersion | Primary ink material for printing conductive electrodes [1] [5]. | High aqueous dispersibility, requires post-print reduction to achieve conductivity. |

| Gold Nanoparticle (AuNP) Ink | Creates highly conductive and plasmonically active patterns for electrochemical and optical sensing [6]. | Excellent biocompatibility and facile surface chemistry for bioconjugation. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) Nanoparticles | Provide selective, antibody-like recognition for target molecules in a core-shell sensor design [3]. | High stability and selectivity; customizable for various analytes. |

| EDC/NHS Crosslinker Kit | Standard chemistry for covalent immobilization of antibodies or aptamers onto COOH-functionalized nanomaterial surfaces [2]. | Activates carboxyl groups to form stable amide bonds with amine-containing biomolecules. |

| Liquid Metal (e.g., EGaIn) Particles | Filler for highly stretchable and conductive composite inks for strain or motion sensors [4]. | Combines fluidic behavior with high conductivity, enabling self-healing composites. |

| Nafion Perfluorinated Resin | A permselective polymer membrane coated on electrodes to reduce fouling from biofluids in wearable sensors [2]. | Blocks interfering anions and large molecules (e.g., proteins) while allowing target analytes (e.g., H₂O₂) to pass. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways in Nanomaterial-Based Biosensing

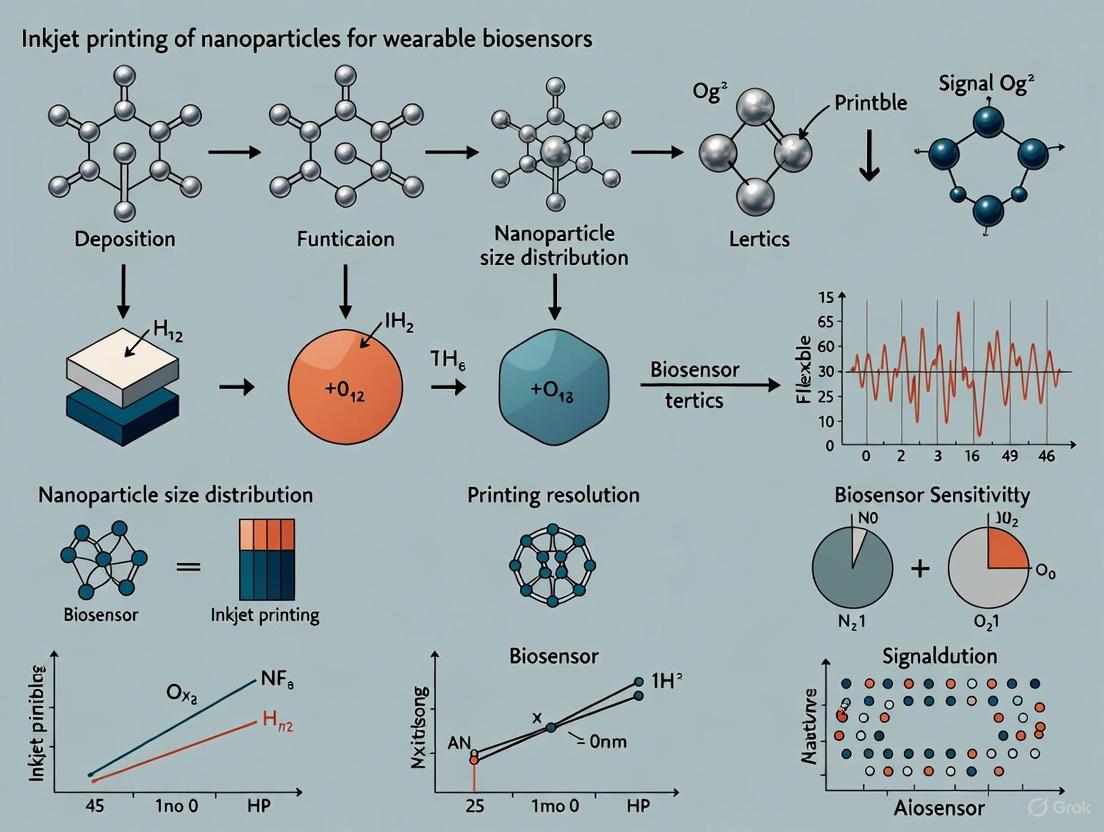

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow for fabricating an inkjet-printed nanomaterial biosensor, from ink formulation to final signal readout, integrating the protocols described above.

Diagram 1: Workflow for fabricating an inkjet-printed nanomaterial biosensor, highlighting key steps from ink formulation to signal readout.

The fundamental signaling mechanism in an electrochemical biosensor, such as one for glucose detection, can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 2: Core signaling pathway of a nanomaterial-based biosensor, showing the sequence from analyte binding to signal generation.

Core-shell cubic nanoparticles represent a significant advancement in nanomaterial design, particularly for applications in wearable and implantable biosensors. These nanoparticles feature a well-defined cubic architecture where a core material is uniformly encapsulated by a shell of another material, creating a single, functionalized unit [7]. This configuration synergistically combines the properties of both components, enabling enhanced functionality that is critical for precise biosensing. In the context of a broader thesis on inkjet printing nanoparticles for wearable biosensors, these structures are paramount. Their design facilitates mass production through printing techniques and allows for the customizable detection of specific biomarkers, including amino acids, vitamins, metabolites, and drugs, directly in complex biological fluids like sweat [7] [8].

The core typically consists of an electroactive material that provides a stable and quantifiable electrochemical signal, acting as the transducer within the sensor [7]. The shell is engineered as a molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP), which functions as a selective capture agent. The cubic morphology is particularly advantageous for manufacturing, as it allows for efficient packing and consistent inkjet printing, enabling the creation of high-density, multiplexed sensor arrays [7]. This architecture is foundational to developing the next generation of personalized health monitoring devices that can provide real-time, continuous biochemical data.

Architectural Deconstruction and Functional Mechanism

The functionality of core-shell cubic nanoparticles is governed by the distinct yet complementary roles of their internal core and external shell.

The Nickel Hexacyanoferrate (NiHCF) Core

The core of these nanoparticles is commonly composed of nickel hexacyanoferrate (NiHCF), a transition metal hexacyanoferrate known for its exceptional electrochemical stability and reversible redox behavior [7]. In a wearable biosensor, this core functions as the signal transduction engine. When the nanoparticle is integrated into an electrochemical sensor and a voltage is applied, the NiHCF core can be cyclically oxidized and reduced. This continuous cycling generates a stable, measurable electrical current, which serves as the baseline signal. The remarkable stability of NiHCF, even in biological fluids, is crucial for the long-term operation of continuous monitoring devices, preventing signal drift and ensuring reliable readings over extended periods [7].

The Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) Shell

The core is enveloped by a molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) shell, which is responsible for the sensor's selectivity. The synthesis of this shell involves polymerizing monomers in the presence of the target biomarker, such as vitamin C or a specific drug molecule [7]. This process, known as template-assisted synthesis, traps the target molecules within the forming polymer matrix. Subsequent washing with a solvent specifically removes these template molecules, leaving behind a polymer shell dotted with nanocavities or holes. These cavities have a three-dimensional shape and chemical functionality that is complementary to the target molecule, acting as artificial antibodies [7].

Integrated Sensing Mechanism

The sensing mechanism is a direct result of the synergistic interaction between the core and the shell, as illustrated in the workflow below:

When a biological fluid containing the target biomarker (e.g., vitamin C in sweat) comes into contact with the sensor, the target molecules selectively bind to the complementary cavities in the MIP shell. The binding of these molecules physically blocks the access of the fluid to the underlying NiHCF core. This blockage impedes the redox reaction at the core surface, leading to a measurable decrease in the electrical current [7]. The degree of signal reduction is quantitatively correlated to the concentration of the target biomarker in the fluid. This core-shell architecture thus directly transcribes a molecular binding event into a quantifiable electrical signal, enabling precise and selective biosensing.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The fabrication and operation of biosensors based on core-shell cubic nanoparticles require a specific set of research reagents and materials. The table below details the key items and their functions.

Table 1: Essential Materials and Reagents for Core-Shell Nanoparticle Biosensors

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Nickel Hexacyanoferrate (NiHCF) Core | Serves as the stable electrochemical transducer. Its redox activity generates the primary electrical signal that is modulated by biomarker binding [7]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) Shell | Provides selective recognition. The nanocavities act as artificial antibodies, specifically capturing target biomarkers based on shape and chemical affinity [7]. |

| Target Biomarker Templates | Molecules (e.g., vitamins, drugs, metabolites) used during synthesis to create the specific recognition cavities within the polymer shell [7]. |

| Functional Monomers | Chemical building blocks that polymerize around the template molecules to form the structure of the shell matrix [7]. |

| Nanoparticle Ink Formulation | A stable colloidal suspension of the core-shell nanoparticles, optimized for viscosity and surface tension to enable reliable inkjet printing of sensor arrays [7]. |

| Flexible Electrode Substrate | The physical support (e.g., polyethylene terephthalate) for the printed sensor array, providing mechanical flexibility for wearable applications [7]. |

| Electrochemical Analyzer | Instrumentation used to apply a controlled voltage to the sensor and measure the resulting current, facilitating the quantification of the target biomarker [7]. |

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

The performance of biosensors utilizing core-shell cubic nanoparticles can be evaluated through several quantitative metrics. The following table compiles key performance aspects based on demonstrated applications.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Core-Shell Nanoparticle Biosensors

| Performance Metric | Details / Value | Context and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Detectable Biomarkers | Vitamins (e.g., Vitamin C), Amino Acids (e.g., Tryptophan), Metabolites (e.g., Creatinine), Drugs (e.g., Busulfan, Cyclophosphamide) [7] [8] | Demonstrates broad-spectrum applicability for monitoring nutrition, metabolism, and therapeutics. |

| Sensing Modality | Electrochemical (Redox signal suppression) | The binding event causes a measurable decrease in current, which is highly reproducible and quantifiable [7]. |

| Key Advantage | Operational stability in biological fluids (e.g., sweat) | Enabled by the highly stable NiHCF core, which is critical for long-term, continuous monitoring required for wearable and implantable devices [7]. |

| Manufacturing Technology | Inkjet Printing | Allows for mass production of robust and flexible biosensors, enabling the creation of multiplexed arrays for multiple biomarkers on a single platform [7]. |

| Application Validation | Metabolic monitoring in long COVID patients; Therapeutic drug monitoring in cancer patients [7] [8] | Validates clinical utility in real-world scenarios, moving from laboratory proof-of-concept to practical healthcare applications. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Synthesis of Molecule-Selective Core-Shell Nanoparticles

This protocol describes the procedure for creating core-shell nanoparticles with a molecularly imprinted polymer shell selective for a target biomarker, adapted from the work of Wang et al. [7].

5.1.1 Materials

- Nickel Hexacyanoferrate (NiHCF) nanocubes

- Target biomarker molecule (e.g., Vitamin C, tryptophan, a chemotherapy drug)

- Functional monomers (e.g., acrylamide, methacrylic acid)

- Cross-linking agent (e.g., N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide)

- Initiator (e.g., ammonium persulfate)

- Solvent (e.g., deionized water or ethanol)

- Washing solvent (specific to the target molecule, for template removal)

5.1.2 Procedure

- Core Dispersion: Disperse the synthesized NiHCF nanocubes in the solvent using sonication to create a homogeneous suspension.

- Template Addition: Add the target biomarker template molecule to the suspension at a defined molar ratio relative to the functional monomers.

- Monomer Assembly: Introduce the functional monomers and cross-linking agent to the solution. Allow the monomers to spontaneously assemble around the template molecules through pre-polymerization interactions.

- Polymerization: Initiate the polymerization reaction by adding the initiator and, if required, applying heat or UV light. This step forms the polymer shell around the NiHCF core, with the template molecules embedded within the polymer matrix.

- Template Extraction: Isolate the nanoparticles via centrifugation and wash them repeatedly with the washing solvent. The solvent is chosen to specifically extract the template molecules without damaging the polymer matrix, leaving behind vacant, shape-complementary cavities.

- Drying and Storage: Re-suspend the nanoparticles in a clean solvent and dry them under an inert atmosphere. Store the finalized core-shell nanoparticles in a desiccator until needed for ink formulation.

Protocol: Inkjet Printing of Biosensor Arrays

This protocol covers the preparation of a nanoparticle ink and its deposition onto a flexible substrate to create a functional biosensor array [7].

5.2.1 Materials

- Synthesized core-shell nanoparticles

- Ink vehicle (e.g., mixture of water, ethylene glycol, and surfactants)

- Flexible polymer substrate (e.g., polyethylene terephthalate (PET))

- Commercial inkjet printer (potentially modified) or specialized industrial printer

- Conducting silver/silver chloride ink (for reference and counter electrodes)

5.2.2 Procedure

- Ink Formulation: Re-disperse the core-shell nanoparticles into the ink vehicle. Optimize the concentration, viscosity, and surface tension of the formulation to prevent clogging of the printer nozzles and to ensure uniform droplet formation.

- Substrate Preparation: Clean the flexible substrate (e.g., PET film) with ethanol and deionized water. Treat the surface with oxygen plasma or a UV-ozone cleaner to enhance the adhesion of the printed ink.

- Printer Setup: Load the formulated nanoparticle ink into the printer cartridge. Use software to design the pattern for the sensor array, defining the location and size of each working electrode.

- Printing: Print the nanoparticle ink onto the predefined areas of the substrate. This step may be repeated to build up multiple layers and increase the density of sensing elements.

- Curing: Dry the printed sensor array at room temperature or in a low-temperature oven (e.g., 60°C) to evaporate the solvent and solidify the film.

- Electrode Completion: Using the conducting ink, print the reference and counter electrodes onto the same substrate to complete the three-electrode electrochemical cell system.

Protocol: Sensor Operation and Data Acquisition for Biomarker Monitoring

This protocol describes the experimental setup and procedure for using the printed biosensor to measure biomarker concentrations in a biological fluid such as sweat [7].

5.3.1 Materials

- Printed biosensor array

- Potentiostat (electrochemical analyzer)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) or artificial sweat solution

- Standard solutions of the target biomarker at known concentrations

- Data acquisition software

5.3.2 Procedure

- Calibration Curve:

- a. Apply a small volume (e.g., 50 µL) of standard solutions with known concentrations of the target biomarker to the sensor.

- b. Using a potentiostat, apply a constant low voltage or a cyclic voltammetry sweep to the working electrode.

- c. Record the stable electrical current generated by the NiHCF core for each standard solution.

- d. Plot the measured current (or the percentage of signal reduction) against the biomarker concentration to generate a calibration curve.

- Sample Measurement:

- a. Collect the biological sample (e.g., via sweat induction).

- b. Apply the sample to the sensor and record the resulting electrical current under the same applied voltage.

- c. Use the calibration curve to interpolate the concentration of the target biomarker in the unknown sample.

The logical sequence of this experimental workflow is summarized in the following diagram:

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) are synthetic materials engineered to possess specific recognition sites for target molecules, functioning as artificial antibodies. Their synthesis involves polymerizing functional monomers in the presence of a target template molecule. Subsequent removal of this template leaves behind cavities that are complementary in shape, size, and chemical functionality to the original molecule, enabling selective rebinding [7]. Within the rapidly advancing field of wearable biosensors, MIPs offer a robust and versatile alternative to biological recognition elements, such as antibodies or enzymes. Their integration with nanoparticle cores and inkjet printing technologies is paving the way for the mass production of durable, selective, and highly sensitive biosensing platforms for continuous health monitoring [9].

The significance of MIPs is particularly evident in applications like wearable metabolic monitoring and therapeutic drug monitoring. For instance, sensors incorporating MIPs have been used to monitor biomarkers such as vitamin C, tryptophan, and creatinine in individuals with Long COVID, as well as to track immunosuppressant drug levels in cancer patients [9]. This Application Note details the protocols for fabricating and utilizing core-shell MIP nanoparticles, with a specific focus on their application in inkjet-printed wearable biosensors.

Core-Shell MIP Nanoparticles: Design and Signaling Mechanism

A transformative design in this field incorporates MIPs as a shell surrounding a stable, redox-active nanoparticle core. This core-shell architecture consolidates target recognition and signal transduction into a single, printable entity [9] [7].

Core-Shell Architecture and Signaling Principle

The core typically consists of a Prussian blue analogue (PBA), with nickel hexacyanoferrate (NiHCF) being identified as exceptionally stable for long-term sensing in biological fluids [9]. The shell is a molecularly imprinted polymer containing tailor-made binding cavities for the target analyte.

The signaling mechanism is based on a steric hindrance model:

- In the absence of the target molecule, the NiHCF core is freely exposed to the surrounding biofluid (e.g., sweat or interstitial fluid), resulting in a strong, measurable electrochemical (redox) signal.

- When the target molecule binds to the complementary cavities in the MIP shell, it obstructs electron transfer between the core and the biofluid.

- This binding event causes a quantifiable reduction in the redox signal, which is inversely proportional to the target concentration [9] [7]. This signal is typically measured using techniques like Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV).

The following diagram illustrates the core-shell nanoparticle's structure and its signaling mechanism upon target molecule binding:

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists the essential materials and reagents required for the synthesis of core-shell MIP nanoparticles and the preparation of printing inks.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Core-Shell MIP Nanoparticle Fabrication

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel Hexacyanoferrate (NiHCF) Nanocubes | Redox-active core for stable electrochemical signal transduction. | Synthesized with citrate chelating agent for uniformity; exhibits zero-strain characteristics for superior longevity [9]. |

| Functional Monomers (e.g., MAA) | Polymer building blocks that form chemical interactions with the target molecule. | Methacrylic acid (MAA) identified via computational docking as optimal for Vitamin C imprinting [9]. |

| Cross-linker (e.g., EGDMA) | Creates a rigid polymer network around the template, stabilizing the imprinted cavities. | Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA) is commonly used. |

| Target Template Molecule | The molecule of interest (analyte) that defines the shape and chemistry of the cavity. | Vitamin C, tryptophan, creatinine, or drugs like cyclophosphamide [9] [7]. |

| Solvent Blend (EtOH, H₂O, NMP) | Dispersion medium for inkjet printing ink; ensures nanoparticle stability and printability. | Optimal blend: Ethanol, Water, and N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) in a 2:2:1 v/v ratio [9]. |

| Poly-L-Lysine (PLL) | Adhesive coating for substrates (e.g., cotton fabric) to enhance ink adhesion and durability. | Positively charged PLL bonds with negatively charged hydroxyl groups on fabrics and CNTs [10]. |

| Carbon Nanotube (CNT) Ink | Establishes primary conductive path on rough textiles and facilitates Ag⁺ reduction. | Used in conjunction with reactive inks on fabric substrates to achieve high conductivity [10]. |

Protocol: Fabrication of MIP/NiHCF Core-Shell Nanoparticles

Synthesis of NiHCF Nanocube Cores

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution containing nickel ions and hexacyanoferrate in deionized water. Incorporate sodium citrate as a chelating agent to control the reaction rate and ensure the formation of highly uniform nanocubes [9].

- Reaction and Precipitation: Allow the reaction to proceed under controlled temperature and stirring. The resulting NiHCF nanocubes should be collected via centrifugation.

- Washing and Characterization: Wash the precipitate thoroughly with water and ethanol. Characterize the nanocubes using Dark-Field Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (DF-STEM) and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) to confirm a uniform size of approximately 100 nm and an even distribution of metal ions [9].

Molecular Imprinting of the Polymer Shell

- Pre-adsorption: Disperse the synthesized NiHCF nanocubes in a solution containing the target molecule (e.g., vitamin C), a suitable functional monomer (e.g., methacrylic acid), and a cross-linker. Allow for pre-adsorption of the monomers and target onto the nanocube surface [9].

- Thermal Polymerization: Induce polymerization by increasing the temperature. This forms a thin, cross-linked polymer layer around the NiHCF core, with the target molecules embedded within [7].

- Template Extraction: Use a suitable solvent to wash away the target molecules from the polymer matrix. This critical step removes the template, leaving behind specific recognition cavities. The success of extraction can be confirmed using Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), where characteristic peaks of the target molecule (e.g., C-Cl bond from cyclophosphamide at ~657 cm⁻¹) disappear [9].

Protocol: Inkjet Printing of Biosensor Arrays

This protocol describes the mass production of flexible biosensor arrays using optimized MIP/NiHCF nanoparticle inks [9] [10].

Ink Formulation and Optimization

- Base Formulation: Re-disperse the synthesized MIP/NiHCF core-shell nanoparticles in a custom solvent blend. The optimized blend identified for stable dispersion and jetability is Ethanol : Water : N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) in a 2:2:1 volume ratio [9].

- Optimization Criteria: Tailor the ink's viscosity, density, and surface tension to meet the specifications of the inkjet printer. Solvents with higher dipole moments help shield nanoparticles from self-interaction and aggregation.

Step-by-Step Printing and Fabrication

The following workflow outlines the complete process for fabricating a fully printed, flexible electrochemical biosensor.

Detailed Steps:

- Substrate Preparation: Treat a flexible substrate (e.g., cotton fabric) with Poly-L-Lysine (PLL). This enhances adhesion between the fabric and subsequently printed nanomaterials through ionic bonding, which is crucial for washability [10].

- Print Conductive Tracks: Load a cartridge with gold nanoparticle ink. Print the Working Electrode (WE), Counter Electrode (CE), and conductive paths with a drop spacing (DS) of 15 µm (equivalent to 1693 dpi) [11].

- Print Reference Electrode: Replace the ink cartridge with one containing silver nanoparticle ink. Print the pseudo-reference electrode (pRE) with a DS of 40 µm (635 dpi) [11].

- Thermal Sintering: Sinter the printed metallic structures in an oven at 120°C for 30 minutes to achieve final electrical properties [11]. For fabric-based sensors, a lower temperature of 100°C for 30 minutes can be used to reduce Ag ions in reactive inks to conductive nanoparticles without damaging the textile [10].

- Print Dielectric Layer: Print a dielectric ink (e.g., PriElex SU8) with a DS of 15 µm as a protective layer to define the active electrode areas and insulate the conductive paths. Cure initially on a hot plate at 100°C, then expose to a UV lamp for 30 seconds for polymerization [11].

- Print Sensing Layer: Finally, print the optimized MIP/NiHCF nanoparticle ink onto the active area of the working electrode. Use a DS of 15 µm [9] [11].

- Final Curing: Cure the biosensor at room temperature for 24 hours to preserve the activity of the imprinted sites and avoid damaging the MIP structure [11].

Performance Metrics and Validation

Rigorous validation is essential to confirm the performance of the printed MIP-based biosensors. The following table summarizes key quantitative data from studies utilizing this technology.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Inkjet-Printed MIP/NiHCF Biosensors

| Analyte/Biomarker | Application Context | Sensing Platform | Key Performance Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid) | Metabolic monitoring in Long COVID patients [9] | Wearable (Sweat) | Successful continuous monitoring in human trials [9] [7]. |

| Tryptophan, Creatinine | Metabolic monitoring in Long COVID patients [9] | Wearable (Sweat) | Successful continuous monitoring in human trials [9] [7]. |

| Immunosuppressants (Busulfan, Cyclophosphamide, Mycophenolic acid) | Therapeutic drug monitoring in cancer patients and a mouse model [9] | Wearable & Implantable | Real-time analysis demonstrated; Monitors drug levels in body [9] [7]. |

| NiHCF Core Material | Long-term operational stability | Electrochemical Testing | Retained cubic structure and exhibited minimal degradation after 5,000 repetitive cyclic voltammetry scans [9]. |

| Cell Viability | Biocompatibility for implantable use | Live/Dead Assay (HDF cells) | High cytocompatibility demonstrated with robust cell viability after culture with 5 and 20 μg mL⁻¹ nanoparticles [9]. |

| Textile-Adhered Conductive Trace | Washability and durability of e-textiles | Electrical Conductivity | Conductivity of 1.25 × 10⁵ S m⁻¹ achieved; performance maintained after bending, ironing, and washing [10]. |

Experimental Validation Protocols

- In Vitro Calibration: Perform calibration curves by measuring the DPV response of the sensor in standard solutions with known concentrations of the target analyte. The signal decrease (ΔI) is plotted against the logarithm of concentration to establish a linear relationship [9].

- Selectivity Testing: Challenge the sensor with solutions containing potential interferents with similar chemical structures. The high selectivity conferred by the MIP cavities should result in a significantly stronger response to the target molecule than to others [9].

- Stability and Durability Testing:

- Operational Stability: Subject the sensor to repeated CV scans (e.g., 50-5,000 cycles) in a relevant buffer like Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) and monitor the signal retention. The NiHCF core demonstrates superior stability compared to other PBAs [9].

- Mechanical Durability (for textiles): Test the sensor's performance after repeated bending cycles (e.g., radius of 1 mm) and after machine washing with detergent to validate robustness for wearable applications [10].

The integration of the molecular imprinting principle with advanced functional nanomaterials and scalable inkjet printing techniques represents a significant leap forward in biosensor fabrication. The detailed protocols outlined in this document—covering the synthesis of core-shell MIP/NiHCF nanoparticles, the formulation of printable inks, and the step-by-step printing of sensor arrays—provide a roadmap for researchers to develop robust, mass-producible biosensors. These sensors hold immense potential for a wide range of applications, from personalized health monitoring and disease management to fundamental physiological investigation, ultimately contributing to the advancement of precision medicine.

The evolution of biosensing technology has ushered in an era of personalized medicine, enabling real-time health monitoring through wearable and implantable devices. Central to the function of these devices are sophisticated signal transduction mechanisms that convert specific biomarker binding events into quantifiable electrical signals. Within the rapidly advancing field of wearable biosensors, inkjet-printed nanoparticle-based platforms have emerged as a transformative approach, combining scalable manufacturing with precise biomarker detection capabilities [1] [9]. These systems leverage nanomaterial innovations to create highly selective, sensitive, and stable sensing interfaces that operate in complex biological environments.

The fundamental challenge in biosensor design lies in establishing a reliable connection between molecular recognition events and measurable electrical outputs. This process, known as signal transduction, forms the core operational principle of all electrochemical biosensors [12] [13]. Recent breakthroughs in core-shell nanoparticle technology have enabled the development of dual-functional materials that integrate both molecular recognition and signal transduction capabilities within a single printable structure [9]. This integration addresses critical limitations in traditional biosensors, including operational instability, limited target diversity, and manufacturing scalability challenges that have hindered widespread adoption in precision medicine applications.

This Application Note examines the signal transduction mechanisms underlying inkjet-printed nanoparticle biosensors, with particular emphasis on their implementation in wearable platforms for continuous health monitoring. We provide detailed experimental protocols for fabricating and characterizing these devices, along with comprehensive performance data to guide researchers in adapting these technologies for specific biomarker detection applications in drug development and clinical diagnostics.

Technical Background

Fundamental Transduction Principles

Electrical biosensors operate on the principle of converting biological recognition events into measurable electrical signals through various transduction mechanisms. The primary categories include:

- Amperometric biosensors: Measure changes in electrical current resulting from redox reactions involving the target analyte at an electrode surface under applied potential [13].

- Potentiometric biosensors: Detect changes in electrical potential (voltage) accumulation at electrode surfaces due to ion concentration changes from biological recognition events [13].

- Impedimetric biosensors: Monitor changes in electrical impedance (resistance to alternating current) resulting from biomarker binding at the electrode interface [13].

- Field-Effect Transistor (FET) biosensors: Utilize semiconductor channels whose conductivity changes in response to charge variations induced by biomarker binding [13].

For wearable applications, the translation of biomarker binding to electrical readout follows a sequential pathway: (1) selective recognition of the target biomarker at the biosensor interface, (2) physicochemical changes induced by the binding event, and (3) conversion of these changes into measurable electrical signals through specialized transducer materials [13] [9].

Core-Shell Nanoparticle Transduction Mechanism

A groundbreaking approach in wearable biosensor design utilizes printable core-shell nanoparticles with built-in dual functionality for both recognition and transduction [9]. These nanoparticles feature a molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) shell that provides customizable target recognition, combined with a redox-active Prussian blue analogue (PBA) core, typically nickel hexacyanoferrate (NiHCF), that generates stable electrochemical signals [9].

The transduction mechanism operates as follows: as target molecules adsorb onto specific binding cavities within the MIP shell, electron transfer between the PBA core and the surrounding biofluid becomes impeded. This reduction in electron transfer efficiency directly decreases the redox signal, which can be precisely quantified using differential pulse voltammetry (DPT) [9]. The NiHCF core provides exceptional stability during prolonged operation in biological fluids, maintaining signal integrity through thousands of redox cycles—a critical advantage for both wearable and implantable applications [9].

Table 1: Comparison of Electrical Biosensor Transduction Mechanisms

| Transduction Type | Measured Parameter | Detection Principle | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometric | Current | Redox reaction current at fixed potential | Metabolites, glucose, neurotransmitters |

| Potentiometric | Voltage | Accumulated charge at electrode interface | Ions, pH, enzyme substrates |

| Impedimetric | Impedance | Resistance to alternating current | Affinity binding, cell growth, pathogens |

| FET-based | Conductivity | Semiconductor channel modulation | Proteins, exosomes, viruses |

| Core-Shell Nanoparticle | Redox signal decrease | Electron transfer impediment | Metabolites, drugs, vitamins |

Materials and Methods

Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of inkjet-printed nanoparticle biosensors requires carefully selected materials and reagents. The following table outlines essential components and their functions in biosensor fabrication and operation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Inkjet-Printed Nanoparticle Biosensors

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel hexacyanoferrate (NiHCF) nanocubes | Redox-active core for signal transduction | Generating stable electrochemical signals in physiological fluids [9] |

| Molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) shells | Selective biomarker recognition | Creating target-specific cavities for vitamins, metabolites, or drugs [9] |

| Methacrylic acid (MAA) monomer | Functional monomer for MIP formation | Optimal binding sites for ascorbic acid detection [9] |

| Glutaraldehyde (GLA) | Crosslinking agent | Enzyme immobilization for reagentless biosensors [14] |

| Functionalized MWCNTs | Electron transfer enhancement | Improving electrochemical signal strength in phosphate sensors [14] |

| Pyruvate oxidase (PyOD) | Enzyme recognition element | Phosphate detection in serum [14] |

| Gold and carbon inks | Conductive electrode fabrication | Printing interconnects and electrode substrates [9] |

| Ethanol/water/NMP solvent blend | Inkjet printing vehicle | Optimal dispersion of MIP/NiHCF nanoparticles [9] |

Core-Shell Nanoparticle Synthesis Protocol

NiHCF Nanocube Synthesis

- Prepare a solution containing citrate as a chelating agent to regulate reaction rates [9].

- Synthesize uniform PBA nanocubes (approximately 100 nm) through controlled precipitation of transition metal ions (nickel, cobalt, copper, or iron) with hexacyanoferrate [9].

- Characterize the resulting nanocubes using dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (DF-STEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) to confirm uniform size distribution and elemental composition [9].

- Perform electrochemical stability testing through repetitive cyclic voltammetry scans (50-5,000 cycles) in phosphate-buffered saline to validate structural integrity, with NiHCF demonstrating superior stability [9].

MIP Shell Formation

- Prepare a solution containing optimal monomer (e.g., methacrylic acid for ascorbic acid detection), crosslinker, and target molecules for pre-adsorption [9].

- Conduct computational screening using automated frameworks such as QuantumDock to identify optimal monomer choices based on binding energies and selectivity against interferents [9].

- Perform thermal polymerization to form a thin MIP layer on the surface of NiHCF nanocubes [9].

- Extract target molecules using appropriate solvents to create selective binding cavities within the MIP shell [9].

- Verify successful MIP formation through Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), monitoring characteristic peak appearance and disappearance during synthesis and extraction [9].

Inkjet Printing Biosensor Fabrication

Ink Formulation and Optimization

- Prepare MIP/NiHCF nanoparticle ink by dispersing core-shell nanoparticles in an optimized solvent blend of ethanol, water, and N-methylpyrrolidone (2:2:1 v/v ratio) to achieve appropriate viscosity (10-12 cP), surface tension (28-32 mN/m), and nanoparticle dispersion for stable jetting [9].

- Formulate enzyme ink for enzymatic biosensors containing pyruvate oxidase (16 U/mL), cofactors (TPP, FAD, MgCl₂, pyruvic acid), functionalized multiwall carbon nanotubes (0.5 mg/mL), bovine serum albumin (2.4% w/v), and Triton X-100 (0.0075% v/v) [14].

- Prepare crosslinking ink containing glutaraldehyde (2.5% w/v) and Triton X-100 (0.006% v/v) for enzyme immobilization [14].

- Characterize ink properties using a viscosimeter and surface tensiometer before printing [14].

Printing and Sensor Assembly

- Utilize a Fujifilm DIMATIX Materials Printer DMP-2831 or similar piezoelectric inkjet printing system [14].

- Print conductive interconnects and electrode substrates using commercial gold and carbon inks [9].

- Deposit MIP/NiHCF nanoparticle ink or enzyme ink onto working electrode areas with optimized printing parameters (waveform, drop spacing, substrate temperature) [9] [14].

- For enzymatic biosensors, sequentially print enzyme layer followed by crosslinking layer (glutaraldehyde) to create a robust immobilized enzyme matrix [14].

- Implement wax printing passivation to define active sensing areas and reduce parasitic currents in permeable substrates [15].

- Cure printed sensors at room temperature or mild heating (≤60°C) to avoid enzyme denaturation [14].

Signal Transduction Measurement Protocols

Electrochemical Characterization

- Perform cyclic voltammetry (CV) in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) from -0.2 to +0.6 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at 50 mV/s scan rate to verify nanoparticle redox activity [9].

- Conduct differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) measurements with parameters: pulse amplitude 50 mV, pulse width 0.05 s, sample width 0.0167 s, pulse period 0.2 s, increment 0.01 V, quiet time 2 s [9].

- For continuous monitoring applications, use chronoamperometry at fixed potential optimal for NiHCF redox reaction (approximately +0.3 V vs. Ag/AgCl) [9].

Biosensor Performance Validation

- Calibrate sensors with standard solutions containing target biomarkers across physiological relevant ranges (e.g., 0-500 μM for metabolites, 0-1000 pg/mL for protein biomarkers) [9] [16].

- Evaluate selectivity by challenging with potential interferents with similar chemical structures [9].

- Assess operational stability through continuous monitoring in artificial biofluids (sweat, serum, urine) for extended periods (24-72 hours) [9].

- Determine shelf-life stability by storing sensors at 4°C and room temperature with periodic performance testing [9] [14].

- Validate clinical performance using human samples (serum, plasma, sweat) from healthy and patient populations with comparison to gold standard methods [9] [16].

Results and Data Analysis

Performance Metrics of Printed Nanoparticle Biosensors

Comprehensive performance characterization of inkjet-printed nanoparticle biosensors reveals their capabilities for diverse biomarker detection applications. The following table summarizes key performance metrics for various biomarker classes.

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Inkjet-Printed Nanoparticle Biosensors for Various Biomarkers

| Target Analyte | Biomarker Class | Linear Detection Range | Limit of Detection | Stability | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C (Ascorbic acid) | Vitamin | 5-500 μM | 1.2 μM | >5000 CV cycles | Long COVID metabolic monitoring [9] |

| Tryptophan | Amino acid | 10-400 μM | 3.5 μM | >5000 CV cycles | Long COVID metabolic monitoring [9] |

| Creatinine | Metabolite | 20-1000 μM | 8.7 μM | >5000 CV cycles | Renal function assessment [9] |

| Immunosuppressants (Busulfan, Cyclophosphamide) | Drugs | 0.1-100 μM | 0.05 μM | 30-day storage stability | Therapeutic drug monitoring [9] |

| Phosphate | Ion | 0.1-10 mM | 0.05 mM | 85% activity after 30 days | Hyperphosphatemia diagnosis [14] |

| BNP | Protein | 25-1000 pg/mL | 5 pg/mL | N/A | Cardiac dysfunction screening [16] |

Signal Transduction Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete signal transduction pathway from biomarker binding to electrical readout in core-shell nanoparticle-based biosensors:

Diagram Title: Core-Shell Nanoparticle Signal Transduction Pathway

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The comprehensive experimental workflow for biosensor fabrication and testing is summarized below:

Diagram Title: Biosensor Fabrication and Testing Workflow

Discussion

Interpretation of Performance Data

The quantitative performance data presented in Table 3 demonstrates the exceptional capability of inkjet-printed nanoparticle biosensors across diverse biomarker classes. The consistently wide linear detection ranges spanning 2-3 orders of magnitude enable monitoring of physiological fluctuations without sample dilution, a critical advantage for continuous monitoring applications [9]. The sub-micromolar limits of detection for metabolites and drugs approach the sensitivity required for tracing subtle metabolic changes in conditions like Long COVID, while the picogram per milliliter sensitivity for protein biomarkers like BNP meets clinical requirements for cardiac assessment [9] [16].

The remarkable stability data, particularly the maintenance of electrochemical signal through >5000 CV cycles for NiHCF-based sensors, represents a significant advancement over traditional Prussian blue (FeHCF) transducers which show substantial degradation after only 50 cycles [9]. This extended operational stability directly addresses one of the fundamental limitations in wearable biosensing—the need for frequent recalibration or replacement due to signal drift [1] [9].

Advantages of Integrated Recognition-Transduction Systems

The core-shell nanoparticle architecture with built-in dual functionality represents a paradigm shift in biosensor design. By integrating molecular recognition (MIP shell) and signal transduction (NiHCF core) within a single nanostructure, these systems eliminate the need for multi-step bioreceptor immobilization procedures that often compromise reproducibility in mass production [9]. The molecular imprinting approach further expands detectable targets beyond the limitations of biological recognition elements (enzymes, antibodies), enabling monitoring of small molecules, vitamins, and drugs that lack natural bioreceptors [9].

The inkjet printing fabrication method provides exceptional manufacturing versatility, allowing rapid prototyping and scale-up with minimal material waste [1] [9] [15]. The compatibility with flexible substrates enables direct integration into wearable platforms such as textiles, skin patches, and implantable devices [1] [17]. The recent demonstration of multiplexed sensor arrays through sequential printing of different MIP/NiHCF formulations further enhances the potential for comprehensive metabolic profiling from minimal sample volumes [9].

Implementation Considerations

Successful implementation of these biosensing platforms requires careful consideration of several practical aspects. The optimization of ink formulations represents a critical step, requiring precise balancing of viscosity, surface tension, and nanoparticle concentration to ensure stable jetting and uniform film formation [9] [14]. For wearable applications, appropriate passivation layers must be incorporated to mitigate biofouling and maintain signal stability in complex biological fluids like sweat and interstitial fluid [17] [9].

The selection of MIP monomers through computational screening approaches significantly enhances development efficiency, enabling rational design of selective recognition interfaces rather than traditional trial-and-error methods [9]. For enzymatic biosensors, the sequential printing of enzyme and crosslinking layers requires precise control of droplet placement and drying conditions to maintain bioactivity while ensuring robust immobilization [14].

Inkjet-printed nanoparticle biosensors represent a transformative technology platform that effectively bridges biomarker binding events with electrical readout through sophisticated signal transduction mechanisms. The core-shell architecture with integrated recognition and transduction functionalities addresses fundamental challenges in biosensor stability, manufacturing scalability, and target diversity. The detailed protocols and performance data provided in this Application Note establish a robust foundation for researchers to implement these technologies across diverse applications in personalized medicine, therapeutic drug monitoring, and clinical diagnostics.

The continued advancement of these systems—through nanomaterial engineering, printing technology optimization, and integration with wireless readout platforms—will further expand their impact in wearable and implantable biosensing. As these technologies mature, they hold significant potential to reshape healthcare monitoring paradigms by providing continuous, real-time molecular data for precision medicine applications.

In the development of inkjet-printed, nanoparticle-based wearable and implantable biosensors, operational stability in biological fluids remains a paramount challenge. The core-shell nanoparticle design, featuring a molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) shell for target recognition and a redox-active core for signal transduction, presents a compelling solution. The composition of this core is critical. While materials like Prussian blue (FeHCF) are commonly used, they often suffer from performance degradation. This Application Note details how the nickel hexacyanoferrate (NiHCF) core functions as a superior, stable foundation, enabling long-term, reliable biosensing in physiologically relevant environments. The data and protocols herein are essential for researchers aiming to develop robust biosensors for applications such as therapeutic drug monitoring and metabolic tracking.

The NiHCF Advantage: Mechanism and Quantitative Stability Data

The NiHCF core's primary role is to provide a stable, electrochemical signal when an electrical voltage is applied in contact with biofluids [7]. Its stability surpasses that of other Prussian blue analogues (PBAs), which is a decisive factor for the operational longevity of wearable and implantable sensors.

Mechanism of Enhanced Stability: The exceptional stability of NiHCF is attributed to its zero-strain characteristics during the repeated insertion and extraction of ions (e.g., Na+, K+) that occur during electrochemical cycling [9]. Substituting iron in Prussian blue with a small-radius metal atom like nickel enhances lattice stability, resulting in minimal structural deformation and capacity fade over thousands of cycles [9].

The following diagram illustrates the core-shell structure of the nanoparticle and the signaling mechanism, highlighting the role of the stable NiHCF core.

Quantitative Stability Comparison: The superior performance of NiHCF was validated through rigorous electrochemical testing. The following table summarizes key comparative data on the stability of different PBA nanocubes.

Table 1: Electrochemical Stability of Prussian Blue Analogue (PBA) Nanocubes

| PBA Composition | Stability Performance in Physiological Fluids | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel Hexacyanoferrate (NiHCF) | Exceptionally High | • Retained cubic structure with minimal degradation after 5,000 repetitive CV scans [9]. • Demonstrated the highest stability among tested PBAs (NiHCF > CoHCF > CuHCF > FeHCF) [9]. |

| Cobalt Hexacyanoferrate (CoHCF) | Moderate | • Experienced substantial loss of crystallographic integrity after prolonged cycling [9]. |

| Copper Hexacyanoferrate (CuHCF) | Moderate | • Showed significant structural degradation after prolonged cycling [9]. |

| Prussian Blue (FeHCF) | Low | • Exhibited poor stability in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) [9]. • Showed reduced redox signals and structural degradation after only 50 repetitive CV scans [9]. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing NiHCF Core Stability

This protocol details the methodology for synthesizing NiHCF nanocubes and evaluating their electrochemical stability, a critical pre-condition for creating reliable biosensors.

Protocol 2.1: Synthesis and Stability Assessment of NiHCF Nanocubes

Objective: To synthesize uniform NiHCF nanocubes and quantitatively evaluate their electrochemical stability in a physiologically relevant fluid using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV).

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Nickel Precursor (e.g., Nickel Chloride, NiCl₂) | Source of Ni²⁺ ions for the formation of the NiHCF crystal lattice. |

| Hexacyanoferrate Salt (e.g., Potassium Hexacyanoferrate, K₄[Fe(CN)₆]) | Source of the [Fe(CN)₆]⁴⁻ ions that coordinate with nickel to form the PBA structure. |

| Citrate Chelating Agent (e.g., Sodium Citrate) | Regulates the reaction rate during synthesis to ensure the scalable production of highly uniform nanocubes [9]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4 | Electrolyte solution that mimics the ionic strength and pH of biological fluids for stability testing. |

Part A: Synthesis of NiHCF Nanocubes [9]

- Solution Preparation: Prepare separate aqueous solutions of the nickel precursor and the hexacyanoferrate salt.

- Controlled Reaction: Under continuous stirring, slowly add the hexacyanoferrate solution to the nickel solution containing a controlled concentration of sodium citrate. The citrate acts as a chelating agent to moderate crystal growth.

- Aging and Purification: Allow the reaction mixture to age at room temperature for several hours to ensure complete crystal formation. Recover the precipitated NiHCF nanocubes via centrifugation.

- Washing: Wash the pellet multiple times with deionized water and ethanol to remove unreacted precursors and by-products.

- Characterization: Confirm the success of the synthesis using Dark-Field Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (DF-STEM) and Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) to verify uniform cubic morphology (approx. 100 nm) and even distribution of Ni and Fe elements [9].

Part B: Electrochemical Stability Testing via Cyclic Voltammetry

- Electrode Modification: Prepare a working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon) by drop-casting a dispersion of the synthesized NiHCF nanocubes.

- Setup: Use a standard three-electrode electrochemical cell with the modified working electrode, a Pt counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, filled with PBS as the electrolyte.

- Continuous Cycling: Run continuous Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) scans. A typical protocol might involve scanning for 5,000 cycles within a suitable potential window (e.g., 0.0 to 1.0 V vs. Ag/AgCl) at a fixed scan rate (e.g., 50 mV/s) [9].

- Data Analysis: Monitor the decay of the redox peak currents and the shift in peak potentials over the thousands of cycles. As per the referenced study, NiHCF should retain >95% of its initial electrochemical activity after 5,000 cycles, demonstrating superior stability compared to other PBAs [9].

The experimental workflow for the synthesis and stability validation is outlined below.

Integrated Biosensor Fabrication and Cytocompatibility

The stability of the NiHCF core is a foundational property that enables the subsequent steps of biosensor fabrication, including the application of the MIP shell and inkjet printing.

Protocol 3.1: Fabrication of the Complete MIP/NiHCF Core-Shell Nanoparticle

- Core Preparation: Begin with synthesized and purified NiHCF nanocubes.

- Pre-adsorption: Immerse the NiHCF nanocubes in a solution containing the target molecule (e.g., a vitamin, metabolite, or drug), a functional monomer (e.g., Methacrylic Acid), and a cross-linker.

- Polymerization: Induce thermal polymerization to form a thin polymer layer around the NiHCF core, entrapping the target molecules.

- Template Extraction: Wash the particles with a solvent to remove the target molecules, creating specific binding cavities within the polymer (MIP) shell. Successful extraction can be confirmed using Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) by observing the disappearance of a characteristic peak of the target molecule [9].

Critical Step: Inkjet Printing

- Ink Formulation: Disperse the custom MIP/NiHCF nanoparticles in an optimized solvent blend (e.g., ethanol, water, and N-methylpyrrolidone in a 2:2:1 v/v ratio) to achieve the required viscosity, density, and surface tension for printing while preventing nanoparticle aggregation [9].

- Printing: Use a commercial inkjet printer to deposit the nanoparticle ink onto flexible substrates alongside commercial gold and carbon inks for interconnects and electrodes, enabling mass production of flexible, multiplexed biosensor arrays [9].

Cytocompatibility Assessment: For any implantable application, confirming the biosafety of the nanomaterials is essential.

- Protocol: Culture human dermal fibroblasts (HDF) in media containing MIP/NiHCF nanoparticles at concentrations of 5 and 20 μg mL−1.

- Viability Assay: Use a commercial live/dead assay kit to assess cell viability after extended culture periods (e.g., 24-72 hours).

- Expected Outcome: The nanoparticles should demonstrate robust cell viability, confirming high cytocompatibility and supporting their potential for in vivo use [9].

The integration of a NiHCF core within printable core-shell nanoparticles directly addresses the critical challenge of operational instability in biological fluids. Quantitative data confirms that NiHCF's zero-strain property provides unparalleled electrochemical durability, maintaining structural and functional integrity through thousands of cycles. This stability, combined with scalable inkjet printing and high cytocompatibility, establishes a robust platform for researchers to develop next-generation wearable and implantable biosensors for precision medicine applications, from long COVID metabolite monitoring to personalized cancer therapeutic drug monitoring.

From Lab to Fabrication: Inkjet Printing and Real-World Applications

Inkjet Printing Protocols for Nanoparticle Deposition and Sensor Mass Production

Inkjet printing has emerged as a transformative digital fabrication technology for the mass production of advanced biosensors. This protocol details methodologies for depositing functional nanomaterial inks onto flexible and textile substrates to create wearable and implantable sensing devices. The document provides a comprehensive framework covering ink formulation, printing optimization, and post-processing, specifically framed within the context of scalable manufacturing for physiological monitoring and personalized healthcare applications. By leveraging computer-aided design and drop-on-demand deposition, inkjet printing enables rapid prototyping and high-throughput production of biosensors with minimal material waste, bridging the gap between laboratory innovation and commercial application [1] [12].

Inkjet printing technology offers a viable solution for the low-cost, rapid, flexible, and mass fabrication of biosensors. As a non-contact, additive manufacturing technique, it allows for precise mask-less deposition of picoliter droplets of functional inks according to digital patterns. This approach presents significant advantages over traditional lithographic methods, which are often impractical, expensive, and wasteful for large-area fabrication on flexible substrates [12]. The technology is particularly suited for developing wearable electronics that combine the precision of digital fabrication with the comfort and flexibility of textiles [1]. The ability to print conductive nanomaterials such as metallic nanoparticles and carbon-based materials directly onto flexible substrates like plastics and textiles has driven innovation in personalized health monitoring, enabling real-time tracking of biomarkers in bodily fluids such as sweat [18] [7].

Quantitative Performance Metrics of Printed Biosensors

The table below summarizes key performance data from recent inkjet-printed biosensor developments, illustrating the capabilities of this technology in real-world applications.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Advanced Inkjet-Printed Biosensors

| Sensor Function / Target Analyte | Printed Nanomaterial | Sensitivity / Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Application Demonstrated | Manufacturing Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurotransmitter Detection (Serotonin) [19] | Carbon Nanotube (CNT) Ink | 42 pM LOD | Biosensor array for high-throughput bioassays | 4-inch wafer scale |

| Microneedle Mechanical Properties [20] | Silver Nanoparticle (AgNP) Ink | Young's Modulus: 15.6 GPa | Minimally invasive plant and biomedical monitoring | Scalable array fabrication |

| Multi-Biomarker Monitoring (e.g., Vitamins, Drugs) [7] | Molecule-Selective Core-Shell Nanoparticles | Not Specified | Long-COVID metabolite & chemotherapy drug monitoring | Mass-producible sensor arrays |

| Acute Kidney Injury Marker (NGAL) [15] | Inkjet-Printed Electrodes | Detection in clinical range | Smartphone-connected urinalysis | Rapid "office-like" prototyping |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Surface Tension-Guided Printing of CNT Transistor Biosensors

This protocol describes an additive method for fabricating carbon nanotube field-effect transistor (CNT FET) biosensors with controlled properties, ideal for high-throughput bioassays [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for CNT FET Biosensor Fabrication

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Carbon Nanotube (CNT) Ink | The functional nanomaterial providing superior electrical properties for the transistor channel. |

| Pre-patterned Electrode Arrays | Serve as the source and drain contacts on a silicon wafer substrate. |

| DNA Aptamers | Biological recognition elements immobilized on the CNT to selectively bind target analytes like serotonin. |

| Solvent Formulation | Aqueous dispersion medium for the CNT ink, engineered for stable jetting and droplet formation. |

Methodology

- Substrate Preparation: Begin with a 4-inch silicon wafer featuring pre-patterned microelectrode arrays. Ensure the substrate is clean and free of organic contaminants.

- Inkjet Printing Setup: Load the CNT ink into a piezoelectric inkjet printhead. Configure the printer waveform (voltage, pulse duration) to achieve stable droplet ejection without satellite drops.

- Precision Deposition: Program the printer to deposit a series of pico-liter droplets of the CNT ink directly onto the gap between the pre-patterned source and drain electrodes.

- Surface Tension-Driven Assembly: Leverage surface tension-guided flow. As the droplet is deposited, capillary forces guide its spread along the hydrophilic electrode surfaces, ensuring the CNT network forms a bridge specifically between the electrodes and preventing unwanted random networks.

- Drying and Curing: Allow the solvent to evaporate at room temperature or on a heated substrate plate, leaving behind a conductive CNT network.

- Functionalization: Incubate the printed CNT FET array with a solution of DNA aptamers specific to the target molecule (e.g., serotonin) to create the biosensing interface.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps of this fabrication process:

Protocol 2: Mass Production of Wearable Sensors Using Core-Shell Nanoparticles

This protocol outlines the synthesis of molecule-selective core-shell nanoparticles and their implementation in mass-printed wearable sensors for monitoring specific biomarkers in sweat [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Core-Shell Nanoparticle Sensor Fabrication

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Nickel Hexacyanoferrate (NiHCF) | The redox-active core material that generates a stable electrical signal in biological fluids. |

| Functional Monomers | Building blocks that polymerize around the target molecule to form a molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) shell. |

| Target Analyte Molecules | The biomarkers (e.g., Vitamin C, tryptophan, drugs) used as templates during MIP synthesis. |

| Flexible Substrate (e.g., Polyester) | The base material (e.g., textile, plastic) for the wearable sensor patch. |

Methodology

Nanoparticle Synthesis (Creating the Ink):

- Core Formation: Synthesize nanoparticles with a core of nickel hexacyanoferrate (NiHCF), a highly stable redox material.

- Molecular Imprinting: Combine the NiHCF cores in a solution with functional monomers and the target biomarker molecule (e.g., vitamin C).

- Polymerization: Initiate polymerization, causing the monomers to assemble spontaneously around the template molecules, forming a polymer shell.

- Template Extraction: Use a solvent to selectively wash away the template biomarker molecules, leaving behind a shell with cavities ("holes") that are shape-specific to the target molecule. These function as artificial antibodies.

Sensor Fabrication by Inkjet Printing:

- Ink Formulation: Disperse the synthesized core-shell nanoparticles in a biocompatible solvent to create a stable, jettable ink.

- Array Design: Design a sensor layout with multiple electrodes. Using a computer-controlled inkjet printer, deposit different nanoparticle inks (each selective to a different biomarker) onto specific working electrodes in a single print run.

- Integration: Print the sensor array directly onto a flexible, textile-based substrate to form a wearable patch.

Sensing Mechanism:

- When the sensor is exposed to sweat, the bodily fluid reaches the NiHCF core through the unoccupied molecular cavities, generating a baseline electrical signal.

- When the target biomarker (e.g., vitamin C) is present, it binds to the shape-matched cavities in the polymer shell, blocking the sweat from contacting the core and causing a measurable decrease in the electrical signal. The signal reduction is proportional to the analyte concentration.

The logical relationship of the sensing mechanism is shown below:

Protocol 3: All-Inkjet-Printed 3D Conductive Microneedles

This protocol describes a single-step, additive method for fabricating 3D conductive microneedles using silver nanoparticle ink, which can be extended to other metallic inks for implantable or transdermal biosensing [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Silver Nanoparticle (AgNP) Ink: Provides the conductive material for the microneedle structure.

- Heated Substrate Plate: Essential for rapid curing of ink droplets to facilitate vertical structure building.

- Flexible Plastic Substrate: The base for the microneedle array.

Methodology

- Printer Setup: Install a thin heater element under the printer's substrate holder. Load a commercial silver nanoparticle ink into a piezoelectric inkjet printhead.

- Temperature Calibration: Set the substrate heater to a temperature high enough to rapidly evaporate the solvent from an incoming droplet (curing it) but low enough to prevent clogging the printhead nozzles with dried ink. This is a critical parameter for successful 3D structuring.

- Digital Fabrication: Program the printer with a series of 2D designs that, when printed layer-by-layer, will form the 3D microneedle structure.

- Layer-by-Layer Printing: Initiate the printing process. The printer jets pico-liter droplets of AgNP ink according to the first layer's design. Upon contact with the heated substrate, the droplets instantly cure, solidifying in place.

- Vertical Construction: The printer proceeds to deposit subsequent layers of ink droplets onto the previously cured layers. The immediate curing upon contact prevents the liquid ink from dripping, allowing for the creation of high-aspect-ratio vertical structures (with height/width ratios up to 20).

- Post-Processing: No thermal sintering is required. The printed microneedles are immediately conductive and ready for mechanical characterization and application testing.

Critical Parameters for Manufacturing Optimization

Successful mass production of inkjet-printed biosensors depends on careful optimization of several inter-related parameters:

- Ink Formulation: The ink must possess the correct viscosity, surface tension, and particle size distribution to ensure reliable jetting and prevent nozzle clogging. The choice of conductive nanomaterial (AgNPs, CNTs, core-shell nanoparticles) determines the sensor's electrical and functional properties [1] [20].

- Substrate-Ink Interaction: The surface energy and porosity of the substrate (textile, plastic, silicon) control droplet spreading and drying dynamics. Pre-treatment or priming of the substrate may be necessary to achieve desired resolution and adhesion [1] [20].

- Printing Dynamics: Waveform parameters (voltage, pulse shape) applied to the printhead piezoelectric element must be tuned for consistent droplet formation and ejection. Nozzle-to-substrate distance and droplet velocity also impact printing quality [19] [12].

- Post-Printing Processing: While some methods enable conductivity without sintering (e.g., chemical sintering or use of heated substrates), others may require mild thermal or photonic treatment to anneal nanoparticles and achieve optimal conductivity and durability, especially for wearable applications that require wash fastness [1] [15].

Inkjet printing provides a robust and scalable protocol set for the deposition of functional nanoparticles and the mass production of biosensors. The techniques detailed herein—from printing 2D CNT transistors and biomarker-selective arrays to 3D conductive microneedles—highlight the versatility of this additive manufacturing approach. The ongoing development of self-healing composites, hybrid printing techniques, and environmentally benign conductive inks is addressing persistent challenges related to durability and sustainability [1]. As the field progresses, cross-disciplinary collaboration and the establishment of standardized testing protocols will be essential to transition these promising laboratory innovations into reliable, commercially available diagnostic and monitoring devices [1] [18].