Preventing Endosomal Damage from Lipid Nanoparticles: Strategies for Safer RNA Therapeutics

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are the leading platform for RNA therapeutic delivery, but their hallmark feature—endosomal escape—is a double-edged sword that can trigger inflammatory responses by causing endosomal membrane damage.

Preventing Endosomal Damage from Lipid Nanoparticles: Strategies for Safer RNA Therapeutics

Abstract

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are the leading platform for RNA therapeutic delivery, but their hallmark feature—endosomal escape—is a double-edged sword that can trigger inflammatory responses by causing endosomal membrane damage. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the fundamental mechanisms of LNP-induced endosomal damage, the cellular sensors that detect this damage, and the resulting inflammatory pathways. It details cutting-edge methodological advances in LNP design, including novel ionizable lipids that minimize membrane disruption and strategies to engage cellular repair machinery. The content further covers troubleshooting and optimization techniques to balance efficient cargo delivery with minimal cellular perturbation, and concludes with validation approaches comparing the efficacy and safety profiles of next-generation LNPs. The synthesis of these perspectives aims to guide the development of safer, non-inflammatory LNP formulations for a broader range of therapeutic applications, including treatment of inflammatory diseases.

The Double-Edged Sword: How LNP Endosomal Escape Triggers Inflammation

The Essential yet Damaging Process of Endosomal Escape

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why does endosomal escape, a desired process, cause damage and inflammation? Endosomal escape is necessary for functional RNA delivery because it allows the genetic cargo to reach the cytosol where it can be translated by ribosomes. However, the mechanism by which LNPs facilitate this escape often involves physically disrupting the endosomal membrane [1] [2]. This disruption is sensed by the cell as damage. Specifically, large, irreparable holes in the endosomal membrane expose glycans to the cytosol, which are detected by proteins called galectins [2]. This galectin binding initiates potent inflammatory signaling pathways, leading to the release of cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α [2].

2. What is the difference between "productive" and "non-productive" endosomal damage? Recent research distinguishes between two types of LNP-induced endosomal damage:

- Productive Damage (Galectin-positive): Membrane damage marked by the recruitment of galectins (particularly galectin-9) is statistically correlated with successful cytosolic release of RNA cargo [1]. This damage is conducive to escape.

- Non-productive Damage (ESCRT-recruited): Membrane perturbations that recruit the Endosomal Sorting Complexes Required for Transport (ESCRT) machinery are typically repaired by the cell and do not permit significant endosomal escape [1]. LNPs that create smaller, reparable holes may thus cause damage without enabling efficient functional delivery [2].

3. What fraction of internalized LNPs successfully triggers RNA release? The process is highly inefficient. Live-cell microscopy studies reveal that only a fraction of internalized LNPs trigger galectin-9 recruitment, which is associated with payload release [1]. Furthermore, even within a damaged endosome, only a small fraction of the total RNA cargo is released into the cytosol [1]. Surprisingly, many endosomes showing galectin-9 recruitment contain no detectable RNA payload at all, a phenomenon more pronounced for mRNA-LNPs than for siRNA-LNPs [1].

4. How can LNP design reduce immunogenicity without compromising delivery efficiency? Strategies focus on engineering the lipids to create a less disruptive escape mechanism:

- ESCRT-Recruiting Ionizable Lipids: A novel class of ionizable lipids can create intermediate-sized holes in the endosome that are recognized and repaired by the ESCRT machinery. This design can produce high expression from mRNA cargo while minimizing galectin-triggered inflammation [2].

- PEG Replacement: Replacing conventional PEG-lipids with alternatives like poly(carboxybetaine) (PCB) lipids can reduce immunogenicity and the "Accelerated Blood Clearance" phenomenon, while also enhancing endosomal escape through better membrane interaction [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Cytotoxicity and Inflammation from LNPs

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Supporting Evidence | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overly disruptive ionizable lipids | Ionizable lipid chemistry and the rate/magnitude of endosomal disruption directly correlate with cytotoxicity [4] [2]. | Screen or design ionizable lipids that recruit the ESCRT repair machinery to create smaller, reparable membrane holes [2]. |

| Formulation-induced excessive galectin signaling | Cytosolic galectin sensors (e.g., galectin-9) detect endosomal damage and drive inflammation; inhibition of galectins abrogates LNP-associated inflammation [2]. | Implement galectin-9 recruitment assays early in screening to identify inflammatory formulations [1] [4]. |

| High anti-PEG antibody response | Anti-PEG antibodies can cause accelerated blood clearance, reduce efficacy, and pose safety risks, especially upon repeated dosing [3]. | Replace linear PEG-lipids with low-immunogenicity alternatives like hydroxyl-PEG (HO-PEG), branched PEGs, or non-PEG alternatives like PCB lipids [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Endosomal Damage with a Galectin-9 Reporter

- Objective: To visualize and quantify LNP-induced endosomal membrane damage in live cells.

- Materials:

- Method:

- Cell Preparation: Seed cells in a glass-bottom imaging dish and transfert with a plasmid expressing a fluorescent galectin-9 protein (e.g., GFP-Gal9).

- LNP Exposure: After 24-48 hours, treat cells with a therapeutically relevant dose of LNPs (e.g., 400 ng/mL for RAW cells [2]).

- Live-Cell Imaging: Use fast live-cell microscopy (e.g., confocal or TIRF) to image cells immediately after LNP addition. Capture images every 5-10 seconds for 1-2 hours [1].

- Data Analysis:

- Quantify the number of galectin-9-positive foci per cell over time.

- Track individual endosomes to identify de novo recruitment events [1].

- Correlate the timing and intensity of galectin-9 recruitment with the presence of fluorescently labeled LNP cargo.

Problem: Low Functional Delivery Efficiency Despite High Cellular Uptake

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Supporting Evidence | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient endosomal escape | Only a small fraction of RNA is released from galectin-marked endosomes; many damaged endosomes contain no detectable RNA [1]. | Optimize the pKa of the ionizable lipid (typically ~6.4-6.5) to improve endosomal membrane disruption and payload release [1]. |

| Payload/lipid segregation | During endosomal sorting, the ionizable lipid and RNA payload can segregate within and across endosomal compartments, preventing coordinated escape [1]. | Develop co-localization assays (using dual-fluorescent LNPs with labeled lipid and RNA) to monitor payload retention during trafficking [1]. |

| Dense PEG coating | The PEG "stealth" layer can act as a physical barrier, reducing LNP-membrane interactions needed for endosomal escape (the "PEG dilemma") [3]. | Use cleavable PEG-lipids (acid- or enzyme-responsive) that shed the PEG layer in the endosome, or replace PEG with PCB lipids that enhance membrane interaction [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Payload and Lipid Co-localization

- Objective: To determine if the RNA payload dissociates from the LNP core during intracellular trafficking.

- Materials:

- Dual-labeled LNPs: LNPs formulated with a fluorescently labeled ionizable lipid (e.g., BODIPY-MC3, green) and fluorescently labeled RNA (e.g., Cy5 or AlexaFluor 647, red) [1].

- Cells: Relevant cell line for your application.

- Method:

- Treatment and Uptake: Incubate cells with dual-labeled LNPs for a set time (e.g., 1-4 hours).

- Fixation and Imaging: Fix cells and image using super-resolution microscopy (e.g., STORM or STED) to achieve high spatial resolution [1].

- Image Analysis:

- Identify individual endosomes and quantify the fluorescence intensity of both the lipid (green) and RNA (red) channels.

- Calculate a correlation coefficient (e.g., Pearson's) for the two signals within single endosomes.

- Identify and count endosomes that are positive for the ionizable lipid but negative for the RNA payload, and vice-versa.

Table 1: Efficiency of Cytosolic RNA Delivery from Galectin-9-Positive Endosomes

This table summarizes key quantitative findings from live-cell imaging studies, highlighting the inefficiencies in the endosomal escape process [1].

| Parameter | siRNA-LNPs | mRNA-LNPs | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fraction of damaged endosomes with detectable RNA ("Hit Rate") | 67% - 74% | ~20% | Live-cell imaging in cultured cells |

| Dose for saturated galectin-9 response | 50 nM (0.72 µg/mL) | 0.75 µg/mL | Dose-response in cultured cells |

| Relative fluorescence intensity per intact LNP | ~2x higher than mRNA-LNP | Baseline | In vitro measurement of fluorescently labeled LNPs |

| Signal increase upon LNP disintegration | ~2.6-fold increase | <20% increase | Treatment with Triton X-100 detergent |

Table 2: Inflammatory Profile Induced by LNP Treatment In Vivo

This table quantifies the pro-inflammatory effects observed in mice after administration of mRNA-LNPs, demonstrating the systemic nature of the response [2].

| Inflammatory Marker | Change after Intratracheal LNP (7.5 µg mRNA) | Change after Intravenous LNP (7.5 µg mRNA) | Cell Culture Model (RAW 264.7 macrophages) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | Significant Increase | Significant Increase | Upregulated by mRNA, empty, and PSS LNPs |

| TNF-α | Significant Increase | Significant Increase | Upregulated by mRNA, empty, and PSS LNPs |

| IFN-β | Significant Increase | Significant Increase | Upregulated by mRNA, empty, and PSS LNPs |

| MCP-1 | Significant Increase | Significant Increase | Upregulated by mRNA, empty, and PSS LNPs |

| BAL Protein | Large, dose-dependent increase (2.5-10 µg dose) | Not Reported | Not Applicable |

| BAL Leukocytes | Large, dose-dependent increase (2.5-10 µg dose) | Not Reported | Not Applicable |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

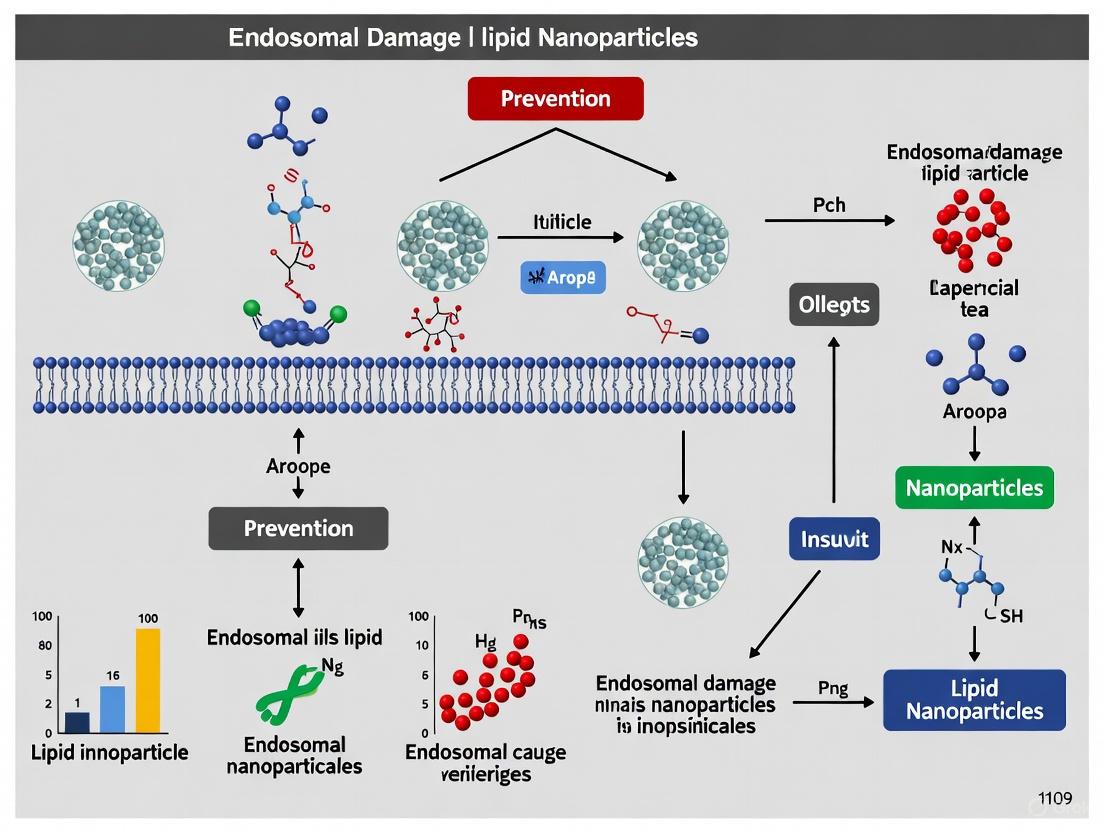

Diagram 1: LNP-induced endosomal damage pathways. This flowchart illustrates the critical juncture after lipid nanoparticle (LNP)-induced endosomal membrane damage. The size of the membrane hole determines the cellular response: large holes trigger galectin-mediated inflammation, while smaller holes are repaired by the ESCRT machinery, minimizing immune activation. RNA release is an inefficient process that can occur from damaged endosomes [1] [2].

Diagram 2: Galectin-9 recruitment assay workflow. This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for using a galectin-9 fluorescent reporter to visualize and quantify LNP-induced endosomal membrane damage in live cells [1] [4] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying and Improving Endosomal Escape

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Feature / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| GFP-Galectin-9 Reporter | A fluorescent biosensor to detect endosomal membrane damage in live cells [1] [4] [2]. | Galectin-9 is a highly sensitive sensor for LNP-induced damage; allows real-time kinetic studies [1]. |

| ESCRT Pathway Inhibitors | Chemical or genetic tools to inhibit the ESCRT machinery (e.g., VPS4 inhibitors) to study its role in mitigating LNP toxicity [2]. | Validates whether a novel LNP formulation creates small, ESCRT-repairable holes versus large, inflammatory ones [2]. |

| Ionizable Lipids (ESCRT-recruiting) | Next-generation lipids designed to create intermediate-sized endosomal holes [2]. | Aims to balance high RNA delivery efficiency with minimal induction of inflammation [2]. |

| PEG Alternatives (e.g., PCB Lipids) | Zwitterionic polymers that replace PEG-lipids in LNP formulations [3]. | Reduce anti-PEG immunogenicity and enhance endosomal escape via membrane interaction, enabling repeated dosing [3]. |

| Dual-Labeled LNPs | LNPs with separately fluorescently tagged ionizable lipids and RNA payload [1]. | Enables study of payload/lipid segregation during endosomal trafficking, a key inefficiency barrier [1]. |

| Branched / Cleavable PEG Lipids | Engineered PEG-lipids designed to reduce immunogenicity [3]. | Branched or Y-shaped PEGs reduce anti-PEG antibody production; cleavable PEGs shed in the endosome to improve membrane contact [3]. |

Core Concept FAQs

What are galectins and what is their primary function in the context of endosomal damage? Galectins are a class of β-galactoside-binding proteins characterized by a conserved carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD). They are among the most widely expressed lectins and function as key sensors of endosomal membrane damage. When lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) create holes in the endosomal membrane during escape, intracellular glycans become exposed to the cytosol. Cytosolic galectins recognize and bind to these exposed glycans, triggering downstream inflammatory signaling pathways [5] [2] [6].

Why is LNP-induced endosomal damage a significant concern for therapeutic development? While endosomal escape is necessary for RNA delivery, the accompanying membrane damage activates inflammation through galectin sensing. This inflammation can be severe and massively aggravate pre-existing inflammatory conditions—by more than 10-fold in some models. This presents a major roadblock for using LNPs in patients with inflammatory diseases (including most elderly and hospitalized patients) and prevents their safe use for treating common inflammatory conditions like heart attack and stroke [5] [2].

What is the difference between galectin-recruited and ESCRT-recruited endosomal damage? The cellular response to LNP-induced endosomal damage depends on the size of the membrane holes:

- Large, irreparable holes are recognized by galectins, which detect exposed glycans and activate inflammatory pathways [5] [2].

- Smaller, reparable holes recruit the Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) machinery, which promotes membrane repair without triggering significant inflammation [5] [2].

The key distinction is that galectin recruitment leads to inflammation, while ESCRT recruitment generally allows for endosomal repair and avoids inflammatory responses.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Inflammation with Efficient RNA Delivery

Observation: Your LNPs provide excellent RNA expression but trigger severe inflammatory responses in vitro and in vivo.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The ionizable lipid creates large, irreparable endosomal holes that trigger galectin-dependent inflammation.

- Solution 1: Reformulate with rapidly biodegradable ionizable lipids. These create smaller, ESCRT-repairable holes that minimize galectin recruitment while maintaining delivery efficiency [5].

- Solution 2: Implement galectin inhibition strategies in your therapeutic approach. Research shows galectin inhibition abrogates LNP-associated inflammation both in vitro and in vivo [5] [2].

- Validation: Monitor galectin-9 recruitment as a marker for inflammatory endosomal damage using live-cell imaging [1].

Problem: Inconsistent Endosomal Escape Efficiency

Observation: Variable transfection efficiency between cell types or experiments, with poor correlation between LNP uptake and functional delivery.

Investigation and Resolution:

- Quantify Actual Escape: Use galectin recruitment as a direct marker for endosomal damage conducive to escape. Only a small fraction of RNA is released from galectin-marked endosomes, and many damaged endosomes contain no detectable RNA cargo due to payload-lipid segregation during endosomal sorting [1].

- Optimize Ionizable Lipid pKa: Ensure ionizable lipids have optimal pKa (typically 6-7) for endosomal membrane interaction. The chemical structure of the ionizable lipid, particularly alkyl chain saturation and branching, critically influences phase transition behavior and escape efficiency [7].

- Balance PEG Content: Address the "PEG dilemma" by optimizing PEGylated lipid percentage. While PEG provides stability and stealth properties, excessive PEG reduces cellular uptake and endosomal escape. Consider biodegradable PEG alternatives [7].

Table 1: Efficiency Metrics of LNP-Mediated RNA Delivery and Associated Damage

| Parameter | siRNA-LNPs | mRNA-LNPs | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endosomal Escape Efficiency | 1-2% of endosomal cargo [7] | Not quantified, but lower than siRNA [1] | Functional cytosolic delivery assessment |

| Galectin-9+ Vesicles with RNA Cargo ("Hit Rate") | 67-74% [1] | ~20% [1] | Live-cell microscopy with fluorescent RNA |

| Dose for Galectin Response Saturation | 50 nM (0.72 µg/mL) [1] | 0.75 µg/mL [1] | Galectin-9 foci quantification |

| Inflammation Exacerbation | >10-fold increase in pre-existing inflammation markers [2] | Similar profile to siRNA-LNPs [2] | Cytokine analysis in disease models |

Table 2: Strategies for Controlling LNP-Induced Inflammation

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Effect on Expression | Effect on Inflammation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Galectin Inhibition | Blocks detection of large endosomal ruptures | Maintains high expression [5] [2] | Abrogated in vitro and in vivo [5] [2] |

| ESCRT-Recruiting Lipids | Creates smaller, reparable membrane holes | Maintains high expression [5] [2] | Minimal inflammation [5] [2] |

| Standard Inflammatory LNPs | Creates large, irreparable holes triggering galectins | High expression [5] | Severe exacerbation of inflammation [5] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Galectin Recruitment via Live-Cell Imaging

Purpose: To visualize and quantify LNP-induced endosomal damage in real-time.

Materials:

- Galectin-9 fluorescent protein construct (e.g., Galectin-9-GFP)

- Confocal or super-resolution live-cell microscopy system

- Cells stably expressing galectin-9-GFP (e.g., RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line)

- Fluorescently labeled LNPs (e.g., with Cy5 or AlexaFluor dyes on RNA)

Procedure:

- Plate galectin-9-GFP expressing cells in glass-bottom imaging dishes 24 hours before experiment.

- Replace medium with imaging-appropriate buffer immediately before assay.

- Add fluorescent LNPs at working concentration (e.g., 0.75 µg/mL for mRNA-LNPs).

- Begin immediate time-lapse imaging using temperature and CO₂ control.

- Acquire images every 30-60 seconds for 1-3 hours to capture damage events.

- Analyze data by tracking de novo recruitment of galectin-9 to vesicular structures containing LNPs.

Key Observations:

- Galectin recruitment typically occurs within 1 hour of LNP addition [1].

- Look for transient or sustained galectin-9 foci that co-localize with LNP signals.

- Note that only a fraction of internalized LNPs trigger galectin recruitment [1].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Inflammatory Response to LNPs

Purpose: To quantify cytokine release and immune activation following LNP administration.

In Vivo Model (Mouse):

- Administer LNPs intratracheally at therapeutically relevant doses (2.5-10 μg mRNA per mouse) [2].

- Euthanize animals 24 hours post-instillation.

- Collect bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and plasma.

- Analyze BAL for protein content (capillary leak marker) and leukocyte count (infiltration marker).

- Measure pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1α, IFN-β) and chemokines (MCP-1) in BAL and plasma using ELISA.

In Vitro Model (Macrophage):

- Expose RAW 264.7 macrophages to LNPs at dose of 400 ng/mL for 6 hours [2].

- Include controls: empty LNPs (no cargo) and LNPs with non-RNA cargo (e.g., PSS).

- Collect supernatant and measure same cytokine panel as in vivo.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids (e.g., cKK-E12, MC3) | Enables RNA encapsulation and endosomal escape | pKa (~6-7) and biodegradability critical for inflammation profile [5] [2] |

| Galectin-9 Fluorescent Constructs | Visualizing endosomal membrane damage | Most sensitive sensor for LNP-induced damage [1] |

| ESCRT Pathway Reporters | Detecting repair-competent membrane damage | Distinguishes inflammatory vs. non-inflammatory escape [5] |

| Cytokine ELISA Kits (IL-6, TNF-α) | Quantifying inflammatory response | Essential for safety profiling of new LNP formulations [2] |

| Biodegradable Ionizable Lipids | Creating ESCRT-recruitable small holes | Key to non-inflammatory, high-expression LNPs [5] |

Mechanism and Workflow Diagrams

LNP Endosomal Escape Pathways

Troubleshooting Experimental Workflow

From Membrane Holes to Inflammatory Signaling Cascades

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our therapeutic mRNA LNPs show good protein expression but also induce high levels of IL-6 in animal models. What is the likely mechanism and how can we mitigate this?

A: The inflammation is likely triggered by endosomal membrane damage during escape. When LNPs create large, irreparable holes in the endosomal membrane, cytosolic galectin proteins recognize exposed glycans and initiate inflammatory signaling cascades, leading to cytokine production including IL-6 [2]. To mitigate this, consider reformulating with ionizable lipids that create smaller, reparable membrane holes. These intermediate-sized holes recruit the ESCRT machinery for repair instead of triggering galectin-mediated inflammation, potentially reducing IL-6 secretion while maintaining expression [2].

Q2: Why do we observe strong inflammatory responses even when using "empty" LNPs with no RNA cargo?

A: Empty LNPs still induce inflammation because the lipid components themselves, particularly through endosomal membrane damage, are sufficient to trigger immune recognition. Studies show that empty LNPs, LNPs loaded with non-RNA cargo, and mRNA-LNPs all upregulate similar pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-β, MCP-1), with empty LNPs sometimes producing the highest cytokine concentrations [2]. This confirms the lipid component and its disruptive interaction with endosomal membranes is a primary driver of inflammation, independent of RNA-mediated immune activation.

Q3: When imaging galectin-positive endosomal damage, we find many damaged endosomes contain no detectable RNA cargo. Does this indicate a problem with our LNP formulation?

A: Not necessarily. Recent research using high-resolution microscopy reveals that RNA payload and ionizable lipid can segregate during endosomal sorting, resulting in galectin-9-positive damaged endosomes that lack detectable RNA [1]. This segregation between the damaging component (ionizable lipid) and cargo (RNA) is a naturally occurring inefficiency in LNP delivery. Focus instead on quantifying the correlation between functional delivery and damage, and consider that hit rates (damaged vesicles with cargo) differ between siRNA (~70%) and mRNA (~20%) LNPs [1].

Q4: What are the key signaling pathways activated by nanoparticle-induced endosomal damage?

A: The primary sensors are galectins that detect membrane damage, but downstream signaling involves multiple pathways. Beyond galectin recognition, LNP-induced membrane damage can activate MAP kinase cascades (ERK, p38, JNK) and redox-sensitive transcription factors like NF-κB and Nrf-2 [8]. Additionally, oxidative stress from nanoparticle interactions can trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation, leading to caspase-1 activation and inflammation [9]. For metallic nanoparticles, Toll-like Receptor (TLR) signaling is also a significant pathway for pro-inflammatory cytokine production [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Managing LNP-Induced Inflammation

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High cytokine secretion | Large, irreparable endosomal holes triggering galectin-mediated inflammation [2] | Reformulate with ESCRT-recruiting ionizable lipids; Consider galectin inhibition strategies |

| Poor expression with low inflammation | Insufficient endosomal escape; Over-optimized for safety [2] | Screen ionizable lipids with pKa ~6.0-6.5; Balance escape efficiency with damage control |

| Variable responses across cell types | Differences in ESCRT machinery or galectin expression [2] | Characterize repair capacity of target cells; Consider cell-specific formulation optimization |

| Cargo-independent inflammation | Lipid composition directly activating immune receptors [10] | Modify ionizable lipid structure; Consider alternative phospholipid components |

| Rapid clearance in vivo | PEG immunogenicity; ABC phenomenon [10] | Optimize PEG lipid anchor and percentage; Consider alternative stealth lipids |

Quantitative Data on LNP-Induced Inflammation

Inflammatory Marker Elevation Following LNP Administration

Table 1: Markers of LNP-induced inflammation in mouse models following intratracheal instillation of cKK-E12 mRNA-LNPs (7.5 μg dose) [2]

| Inflammatory Marker | Fold Increase vs Control | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| BAL Protein Content | Large, dose-dependent increase [2] | Capillary leak, lung barrier dysfunction |

| BAL Leukocyte Count | Large, dose-dependent increase [2] | Immune cell infiltration to alveoli |

| IL-6 | Significantly increased [2] | Pro-inflammatory cytokine, acute phase response |

| TNF-α | Significantly increased [2] | Pro-inflammatory cytokine, systemic inflammation |

| IFN-β | Significantly increased [2] | Type I interferon, antiviral state induction |

| MCP-1 | Significantly increased [2] | Chemokine, monocyte recruitment |

Table 2: Comparison of inflammatory responses across administration routes for cKK-E12 mRNA-LNPs [2]

| Administration Route | Tissue Cytokine Profile | Systemic Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Intratracheal | Upregulation of IL-1α, IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-β, MCP-1 in BAL fluid [2] | Local lung inflammation, hepatization |

| Intravenous | Upregulation of same cytokines in plasma [2] | Leukocytosis, lymphopenia, neutrophilia, liver/spleen inflammation |

| Intradermal | Significant cytokine upregulation in skin tissues [2] | Local skin inflammation |

LNP Formulation Comparison Data

Table 3: Cationic lipid comparison for reactogenicity and immunogenicity in mouse study (5 μg unmodified spike mRNA, intramuscular) [11]

| Lipid Type | Lipid Name | Particle Size (nm) | Zeta Potential (mV) | Encapsulation Efficiency | Post-Prime Weight Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permanent Cationic | DOTMA | 63-149 [11] | +20.7 [11] | >88% [11] | 3-6% (transient) [11] |

| Ionizable | ALC0315 | 63-149 [11] | Not specified | >88% [11] | 3-6% (transient) [11] |

| Various Ionizable | 4 other structures | 63-149 [11] | Not specified | >88% [11] | 3-6% (transient) [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Endosomal Damage via Galectin Recruitment

Purpose: To visualize and quantify LNP-induced endosomal membrane damage using galectin markers [2] [1].

Materials:

- Galectin-9 translocation reporter (e.g., GFP-galectin-9)

- Appropriate cell line (e.g., RAW 264.7 macrophages, primary target cells)

- LNP formulations to test

- Live-cell imaging setup with environmental control

- Fixatives if performing endpoint assays

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Plate cells in appropriate imaging chambers 24 hours prior to experiment to achieve 60-70% confluence.

- Transfection: Transfert cells with GFP-galectin-9 construct using standard methods and allow 24-48 hours for expression.

- LNP Exposure: Add LNPs at working concentration (e.g., 50 nM for siRNA-LNPs, 0.75 μg/mL for mRNA-LNPs) directly to imaging medium [1].

- Image Acquisition:

- Begin time-lapse imaging immediately after LNP addition

- Capture images every 2-5 minutes for 1-4 hours

- Maintain temperature at 37°C with 5% CO₂

- Quantification:

- Count galectin-9 positive foci per cell over time

- Calculate percentage of LNP-containing endosomes that recruit galectin-9

- Note intensity and duration of galectin recruitment

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If background galectin signal is high, serum-starve cells for 1-2 hours before imaging

- Optimize LNP dose in pilot experiments to avoid saturation of damage response

- For co-localization studies, use fluorescently labeled LNPs with distinct emission spectrum from GFP

Protocol 2: Evaluating ESCRT Recruitment to Damaged Endosomes

Purpose: To determine if LNP formulations create reparable membrane holes that recruit ESCRT machinery instead of triggering inflammation [2].

Materials:

- ESCRT component reporters (e.g., CHMP4B-GFP, VPS4-mCherry)

- Standard cell culture reagents and equipment

- Confocal or super-resolution microscope

- LNP formulations with varying ionizable lipids

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Seed cells expressing ESCRT component fluorescent reporters.

- LNP Exposure: Treat cells with test LNPs at therapeutically relevant concentrations.

- Fixation and Staining: At predetermined timepoints (30-120 minutes post-treatment), fix cells and immunostain for endosomal markers (e.g., Rab5, Rab7, LAMP1).

- Image Analysis:

- Quantify co-localization between ESCRT components and endosomal markers

- Compare ESCRT recruitment between LNP formulations

- Correlate with galectin recruitment in parallel experiments

- Functional Assessment:

- Measure cytokine production (IL-6, TNF-α) from same treatments

- Assess mRNA expression efficiency

Interpretation: Formulations that recruit ESCRT machinery without significant galectin recruitment typically show reduced inflammation while maintaining therapeutic efficacy [2].

Protocol 3: In Vivo Assessment of LNP-Induced Inflammation

Purpose: To evaluate the inflammatory potential of LNP formulations in animal models [2].

Materials:

- Appropriate animal model (e.g., C57BL/6 mice)

- Test LNP formulations

- Control LNPs (empty, known inflammatory, known non-inflammatory)

- Equipment for desired administration route (intravenous, intratracheal, intramuscular)

- BAL collection supplies or blood collection tubes

- Cytokine ELISA kits (IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-β, MCP-1)

Procedure:

- Dosing: Administer LNPs at therapeutically relevant doses to experimental animals.

- Sample Collection:

- For intratracheal administration: Collect bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid at designated timepoints (e.g., 2, 6, 24 hours)

- For systemic administration: Collect plasma/serum at similar timepoints

- Inflammatory Marker Analysis:

- Quantify total protein in BAL fluid (capillary leak marker)

- Count leukocytes in BAL fluid (immune cell infiltration)

- Measure cytokine levels via ELISA

- Histopathology:

- Harvest relevant tissues (lung, liver, spleen)

- Process for H&E staining

- Score for inflammatory changes

Data Interpretation: Compare inflammatory markers between test formulations and controls. Effective non-inflammatory LNPs should show significantly reduced inflammatory parameters while maintaining target engagement.

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Reagents for Studying LNP-Induced Endosomal Damage

Table 4: Key research reagents for investigating LNP-endosomal interactions and inflammation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane Damage Reporters | GFP-galectin-3, GFP-galectin-9, RFP-galectin-4 [2] [1] | Live-cell imaging of endosomal rupture | Galectin-9 is most sensitive for LNP damage; optimize expression levels |

| ESCRT Machinery Reporters | CHMP4B-GFP, VPS4-mCherry, TSG101 antibodies [2] | Detect reparable vs. irreparable membrane damage | Co-stain with late endosome markers for localization |

| Ionizable Lipids | cKK-E12 (inflammatory reference), ESCRT-recruiting lipids [2] | Structure-function studies of escape vs. inflammation | Screen pKa values ~6.0-6.5 for optimal endosomal activity |

| Cytokine Detection | IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-β, MCP-1 ELISAs [2] | Quantify inflammatory responses | Measure multiple timepoints (2-24h) for complete profile |

| Endosomal Markers | Rab5-GFP (early), Rab7-RFP (late), LAMP1 antibodies [1] | Track LNP trafficking through endocytic pathway | Use super-resolution for precise localization |

| Fluorescent LNP Components | BODIPY-MC3 (lipid), Cy5-mRNA, AF647-siRNA [1] | Visualize cargo/lipid segregation and fate | Account for fluorescence quenching in intact LNPs |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary cellular sensors used to detect and quantify LNP-induced endosomal damage? The primary sensors for LNP-induced endosomal damage are cytosolic galectin proteins, particularly galectin-9 and galectin-8. These proteins contain carbohydrate recognition domains that bind to β-galactoside sugars. When endosomal membranes are damaged, these normally hidden glycans on the inner leaflet are exposed to the cytosol. Galectins rapidly recruit to these sites, forming fluorescent puncta that can be imaged and quantified. Galectin-9 is noted as the most sensitive sensor for damages induced by LNPs and small molecule drugs [1] [12].

Q2: Why is the functional delivery of RNA cargo so inefficient despite observed endosomal damage? Research reveals multiple layers of inefficiency. Even when LNPs trigger galectin-9-positive endosomal damage, functional RNA release is not guaranteed. Key factors include:

- Cargo-Payload Segregation: The ionizable lipid and RNA cargo can segregate during endosomal sorting, meaning a damaged endosome may not contain the therapeutic payload [1].

- Low Release Fraction: Only a small fraction of the RNA cargo present in a damaged endosome is actually released into the cytosol [1].

- Variable Damage Response: The cell can activate the ESCRT (Endosomal Sorting Complexes Required for Transport) machinery to repair smaller membrane holes, preventing escape. Only larger, irreparable holes lead to significant galectin recruitment and potential release [2].

Q3: How can I experimentally distinguish between productive and non-productive endosomal damage? Simultaneous live-cell imaging of multiple markers is required. You should track:

- Damage: Using a fluorescent reporter like mCherry-Galectin9.

- Cargo: Using fluorescently labeled RNA (e.g., Cy5-mRNA).

- Repair Machinery: Using fluorescently tagged ESCRT components (e.g., CHMP4b). Productive escape events are typically characterized by strong, sustained galectin-9 recruitment co-localized with the RNA cargo, and an absence of ESCRT machinery. In contrast, ESCRT recruitment indicates repair and likely non-productive damage [2] [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low or Inconsistent Endosomal Escape Efficiency

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Suboptimal Ionizable Lipid Properties The pKa and chemical structure of the ionizable lipid are critical. The lipid should have a pKa between 6.0-6.5 to protonate efficiently in the early endosome. A cone-like structure (with unsaturated or branched tails) promotes the transition to an inverted hexagonal phase in the endosomal membrane, facilitating escape [7].

Cause 2: The "PEG Dilemma" PEGylated lipids are essential for LNP stability and reducing opsonization, but they can also create a steric barrier that inhibits cellular uptake and fusion with the endosomal membrane, thereby reducing escape [7].

- Solution: Optimize the molar percentage of PEG-lipid in your formulation. Consider using exchangeable PEG-lipids that dissociate over time or exploring biodegradable PEG alternatives like polyoxazolines [7].

Cause 3: Inadequate Quantification Method Standard confocal microscopy and flow cytometry lack the resolution to accurately quantify individual endosomal escape events, which are rare, fast, and occur at the nanoscale [13].

- Solution: Implement advanced nanoscopy techniques. Super-resolution microscopy (e.g., STED, SMLM) or electron microscopy (EM) provide the necessary resolution to visualize and quantify endosomal damage and cargo release at the single-vesicle level [13].

Problem: High Cytotoxicity and Inflammation from LNPs

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Excessive Endosomal Damage Triggering Potent Immune Responses

Large, irreparable endosomal holes trigger robust galectin recruitment, which initiates inflammatory signaling pathways, leading to the release of cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α [2].

- Solution 1: Develop "stealth" LNPs that create smaller, reparable holes. Certain ionizable lipid classes generate intermediate-sized membrane perturbations that recruit the ESCRT repair machinery instead of galectins. This allows for sufficient RNA expression while minimizing inflammatory activation [2].

- Solution 2: In experimental models, genetic or pharmacological inhibition of galectins has been shown to abrogate LNP-associated inflammation without completely blocking RNA expression [2].

Quantitative Data on Endosomal Escape Efficiency

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent research, highlighting the profound inefficiencies in the LNP delivery process.

Table 1: Quantifying the Intracellular Barriers to LNP Delivery

| Inefficiency Barrier | Quantitative Measure | Experimental Method | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall siRNA Release per Endosome | Only 1% - 2% of encapsulated siRNA is released into the cytosol. | Super-resolution microscopy, functional assays | [7] |

| Endosomal Damage without Cargo | For mRNA-LNPs, ~80% of galectin-9 positive damaged endosomes contained no detectable mRNA. | Live-cell microscopy, vesicle tracking | [1] |

| Endosomal Damage with Cargo | For siRNA-LNPs, ~70% of galectin-9 positive damaged endosomes contained siRNA. | Live-cell microscopy, vesicle tracking | [1] |

| LNP Uptake vs. Damage | Only a fraction of internalized LNPs trigger galectin-9 recruitment. | Correlative live-cell imaging | [1] |

Table 2: Comparison of Microscopy Techniques for Quantifying Endosomal Escape

| Technique | Resolution (XY) | Suitable for Live-Cell Imaging? | Quantification Capability | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confocal Microscopy | ~200 nm | Yes | Worst (Low resolution, cannot resolve single NPs) | Simple, accessible, multi-color [13] |

| Electron Microscopy (EM) | ~1 nm | No | Good (Direct visualization and counting) | Highest resolution, definitive localization [13] |

| SMLM (e.g., PALM/STORM) | ~20 nm | No (in most cases) | Good (Single-molecule counting) | Molecular-scale resolution, single-molecule counting [13] |

| STED | ~50 nm | Yes | Good | Super-resolution in live cells [13] |

| CLEM (Correlative Light-EM) | ~1 nm (EM) | No | Best (Combines dynamics with ultrastructure) | Correlates functional data with high-resolution structure [13] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Galectin-9 Imaging Assay for Endosomal Damage

This protocol uses a stable cell line expressing a fluorescent galectin-9 reporter to quantify LNP-induced endosomal damage [12].

Workflow:

Detailed Methodology:

- Reporter Cell Generation: Generate stable cell lines (e.g., Huh7, HepG2) expressing mCherry-tagged galectin-9 using a knock-in strategy (e.g., AAVS1 ZFN-targeting) [12].

- Cell Seeding: Plate reporter cells in a 96-well or 384-well optical-bottom imaging plate and culture until ~80% confluent.

- LNP Treatment: Add LNPs containing fluorescently labeled RNA (e.g., Cy5-mRNA) to the cells. Include a positive control (e.g., 10 µM UNC2383 small molecule) and a negative control (vehicle). Add a nuclear stain (e.g., Hoechst) to assess cytotoxicity via nuclear morphology [12].

- Image Acquisition: Use a high-throughput automated microscope for live-cell, time-lapse imaging. Capture images every 30-60 minutes for 6-24 hours using channels for mCherry (damage), Cy5 (cargo), and Hoechst (nuclei) [12].

- Image Analysis: Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, CellProfiler) to:

- Count the number of mCherry-Gal9 puncta per cell over time.

- Measure the co-localization between mCherry-Gal9 puncta and Cy5-RNA signal.

- Analyze nuclear size and intensity in the Hoechst channel to infer compound toxicity [12].

Protocol 2: Correlative Microscopy to Analyze LNP and Cargo Segregation

This protocol combines live-cell dynamics with high-resolution electron microscopy to visualize the disintegration of LNPs and segregation of components inside endosomes [1].

Detailed Methodology:

- Prepare Dual-Labeled LNPs: Formulate LNPs where both the ionizable lipid (e.g., conjugated to BODIPY) and the RNA cargo (e.g., labeled with Cy5) are fluorescently tagged [1].

- Live-Cell Imaging: Treat cells with dual-labeled LNPs and perform live-cell imaging to track the co-localization of the lipid and RNA signals over time in endosomes, particularly those recruiting galectin-9.

- Chemical Fixation: At a time point of interest (e.g., when galectin recruitment is observed), rapidly fix the cells with a suitable fixative (e.g., glutaraldehyde) for EM processing.

- Sample Processing for EM: Process the fixed cells for EM analysis, which includes dehydration, resin embedding, and ultramicrotomy to produce thin sections.

- Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy (CLEM):

- Use the fluorescent signals from the live-cell imaging to map the regions of interest.

- Image the same regions in the EM sections to achieve high-resolution visualization of the endosomal ultrastructure, LNP morphology, and the spatial relationship between LNPs and the endosomal membrane [1].

- Analysis: Quantify the ratio of endosomes where lipid and RNA signals have segregated. Look for visual evidence of LNP disintegration and ionizable lipid enrichment in the endosomal membrane [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Endosomal Damage and Escape

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| mCherry-Galectin9 Reporter Cell Line | Live-cell sensor for endosomal membrane damage. | High-throughput screening of LNP formulations; quantifying damage kinetics [12]. |

| Fluorescently Labeled RNA (Cy5-mRNA/siRNA) | Visualizing the location and trafficking of LNP cargo. | Determining cargo co-localization with damage markers; quantifying release efficiency [1] [12]. |

| Antibodies to Endosomal Markers (Rab5, Rab7, LAMP1) | Marking different stages of the endolysosomal pathway. | Identifying the subcellular location of LNP accumulation and damage via immunofluorescence [14] [15]. |

| ESCRT Machinery Reporters (e.g., CHMP4b-GFP) | Sensor for endosomal membrane repair pathways. | Distinguishing between reparable (non-leaky) and irreparable (leaky) membrane damage [2]. |

| Ionizable Lipids (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA, SM-102) | Core functional component of LNPs for endosomal escape. | Formulating LNPs; studying structure-function relationships for efficient, low-inflammatory delivery [2] [7]. |

Visualizing the Endosomal Damage and Escape Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the key cellular decision point that determines whether endosomal damage leads to productive RNA escape or non-productive inflammation/repair.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Endosomal Damage and Cytotoxicity

FAQ: Why do my Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) cause high cytotoxicity in cell cultures, even with modified, non-immunogenic mRNA?

The cytotoxicity is likely driven by the LNP components themselves, not the mRNA cargo. Research shows that changing or even removing the mRNA cargo does not significantly affect cytotoxicity, indicating that the cell response is primarily driven by the lipid components [4] [16]. The key mechanism is endosomal disruption; the rate and magnitude of this disruption directly correlate with observed cell toxicity [4] [2].

FAQ: My LNP formulations show good cellular uptake but poor functional protein expression. What is the bottleneck?

This is a common issue where endosomal escape has failed. While uptake may be efficient, the majority of internalized LNPs are degraded in the lysosome or have their payloads recycled outside the cell [17]. Only a very small fraction of RNA payload is successfully released into the cytosol [1]. The endosomal escape step is a major bottleneck for functional delivery.

FAQ: I observe strong inflammatory responses in my in vivo models after LNP administration. Is this caused by the RNA or the delivery system?

Both can contribute, but the LNP itself is a potent inflammatory trigger. Even empty LNPs (with no RNA cargo) can induce comparable pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) and act as a strong adjuvant [2]. This inflammation is mechanistically linked to endosomal damage. When the endosomal membrane is disrupted, it is sensed by cytosolic galectin proteins, which subsequently trigger inflammatory pathways [2].

FAQ: How can I design safer LNPs that minimize endosomal trauma but maintain high delivery efficiency?

Focus on the chemical design of the ionizable lipid. Recent studies show that a unique class of ionizable lipids can create smaller, repairable holes in the endosome [2]. These smaller holes are recognized and repaired by the ESCRT (Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport) machinery, allowing for cargo release while minimizing the activation of inflammatory galectin sensors [2]. Furthermore, biodegradable lipids (e.g., those with ester bonds in the acyl tails) are designed to reduce cellular accumulation and can improve safety profiles [16].

The table below summarizes key quantitative relationships between endosomal damage and cellular consequences, as established in recent research.

| Observed Phenomenon | Quantitative Relationship | Experimental Context | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endosomal Damage vs. Cytotoxicity | Direct correlation between the rate and magnitude of endosomal disruption and measured cytotoxicity. | In vitro models using Galectin-9 reporter systems. | [4] |

| LNP-induced Inflammation | Intratracheal LNP instillation (7.5 µg mRNA dose) caused a >10-fold increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α) and severe lung "hepatization". | In vivo mouse model. | [2] |

| Inefficient Endosomal Escape | Only ~1-2% of internalized siRNA is released into the cytoplasm from endosomes/lysosomes. | Study of ionizable lipid nanoparticle delivery. | [18] |

| RNA-less Damaged Endosomes | A high percentage of LNP-damaged endosomes (~80% for mRNA-LNPs; ~26-33% for siRNA-LNPs) contain no detectable RNA cargo. | Live-cell microscopy of vesicles with galectin-9 recruitment. | [1] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Endosomal Disruption Kinetics Using a Galectin-9 Reporter

Purpose: To systematically measure LNP-induced endosomal membrane damage and its relationship to cargo expression and cytotoxicity [4].

Key Reagents & Cells:

- Cells: Primary Human Dermal Fibroblasts (NHDFs) or other physiologically relevant cell types [16].

- Reporter: Fluorescently tagged Galectin-9 (e.g., Galectin-9-GFP) [2].

- LNPs: Formulations with fluorescently labeled cargo (e.g., Cy5-mRNA) to track uptake.

Methodology:

- Cell Culture & Transfection: Culture NHDF cells in media supplemented with varying concentrations of FBS (e.g., 2% and 10%) to assess the impact of serum proteins. Transfert cells with the Galectin-9-GFP construct.

- LNP Application: Apply LNPs containing Cy5-labeled mRNA to the cells. Use a range of doses to establish a dose-response profile.

- Live-Cell Imaging & Kinetic Analysis: Use confocal or live-cell microscopy to track, in real-time:

- Cellular Uptake: Quantify the fluorescence intensity of Cy5 signal inside cells.

- Endosomal Disruption: Quantify the recruitment and fluorescence intensity of Galectin-9-GFP to endosomal membranes.

- Cargo Expression: If the mRNA encodes a reporter like eGFP, quantify its expression over time.

- Cytotoxicity Assessment: In parallel, perform a standard cytotoxicity assay (e.g., LDH release, MTT) at relevant time points post-LNP application.

- Data Correlation: Correlate the kinetic data (uptake rate, peak Galectin-9 signal, time to Galectin-9 recruitment) with both final cargo expression levels and cytotoxicity metrics [4] [16].

Protocol 2: Differentiating Endosomal Damage Sensor Pathways

Purpose: To determine whether LNPs create large, irreparable holes (recruiting galectins) or smaller, repairable holes (recruiting the ESCRT machinery) [2].

Key Reagents & Cells:

- Cells: RAW 264.7 macrophages or other immune-responsive cells.

- Reporters: Fluorescently tagged Galectin-3 and an ESCRT component, such as CHMP4B [2].

- LNPs: Formulations with different ionizable lipids (e.g., traditional cKK-E12 vs. novel ESCRT-recruiting lipids).

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Seed cells expressing the fluorescent damage sensors (Galectin-3 and CHMP4B).

- LNP Exposure: Treat cells with the different LNP formulations.

- High-Resolution Imaging: At defined time points post-treatment, fix the cells and image using super-resolution microscopy.

- Phenotype Classification: Categorize damaged endosomes based on the primary sensor recruited:

- Galectin-Dominant: Vesicles with strong Galectin-3 signal indicate large, irreparable membrane damage.

- ESCRT-Dominant: Vesicles with strong CHMP4B signal indicate smaller, repairable damage.

- Functional Correlation: Measure the inflammatory cytokine output (e.g., via ELISA for IL-6, TNF-α) from cells treated with each LNP type. LNPs that preferentially recruit the ESCRT machinery should demonstrate high cargo expression with minimal inflammation [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table lists essential reagents and their functions for investigating endosomal trauma.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Galectin-9 (Fluorescent Reporter) | A highly sensitive sensor for detecting endosomal membrane damage/rupture. Recruitment indicates major endosomal disruption [4] [2]. |

| Ionizable Cationic Lipids (e.g., MC3, cKK-E12) | The primary LNP component responsible for endosomal escape. Its chemical structure (headgroup pKa, tail saturation) dictates the efficiency and toxicity of membrane disruption [16] [2]. |

| ESCRT Pathway Reporters (e.g., CHMP4B) | Markers for the cellular machinery that repairs small holes in endosomal membranes. Recruitment is associated with lower inflammation [2]. |

| Modified mRNA (e.g., N1-methyl-pseudouridine) | mRNA with modified nucleosides reduces innate immune recognition by the cell, helping to isolate lipid-induced toxicity from RNA-induced immunogenicity [16]. |

Signaling Pathways in Endosomal Trauma

The diagram below illustrates the two primary cellular pathways activated by LNP-induced endosomal damage.

Endosomal Damage Sensing Pathways

Experimental Workflow for Cytotoxicity Analysis

This diagram outlines a logical workflow for troubleshooting LNP-induced cytotoxicity in an experimental setting.

Cytotoxicity Analysis Workflow

Engineering Gentler LNPs: Lipid Design for Minimal Membrane Disruption

FAQs: Troubleshooting Ionizable Lipids and LNP Formulation

Q1: Our LNP formulations are triggering significant inflammatory responses in vivo. What is the mechanism, and how can we mitigate this?

A1: Inflammation is often a direct result of endosomal damage caused by the ionizable lipid. During endosomal escape, some lipids create large, irreparable holes in the endosomal membrane. These holes are sensed by cytosolic proteins called galectins (particularly galectin-9), which initiate a potent inflammatory cascade, leading to the secretion of cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α [2] [1]. Solution: To mitigate this, focus on developing ionizable lipids that create smaller, more transient pores in the endosomal membrane. These smaller holes can be repaired by the cellular ESCRT (Endosomal Sorting Complexes Required for Transport) machinery, thereby preventing galectin sensing and subsequent inflammation. Research shows that LNPs engineered to recruit the ESCRT pathway can achieve high cargo expression with minimal inflammatory side effects [2].

Q2: We are experiencing low RNA delivery efficiency despite high cellular uptake. What are the key intracellular barriers?

A2: Our analysis identifies multiple distinct inefficiencies in the cytosolic delivery pathway [1]:

- Inefficient Endosomal Damage: Only a fraction of internalized LNPs successfully trigger endosomal membrane damage (marked by galectin recruitment) conducive to cargo release.

- Inefficient Cargo Release: Even in galectin-positive damaged endosomes, only a small fraction of the RNA cargo is actually released into the cytosol.

- Component Segregation: During endosomal sorting, the ionizable lipid and RNA payload can segregate from each other, both within single endosomes and across different compartments. This means an endosome can be damaged by the ionizable lipid yet contain little to no RNA, preventing functional delivery [1].

Q3: How can we improve the thermostability of our mRNA-LNP formulations to avoid the need for cryogenic storage?

A3: A major cause of mRNA instability in LNPs is the generation of reactive aldehyde impurities from the degradation of the ionizable lipid. These aldehydes covalently bind to mRNA nucleosides, inactivating them [19]. Solution: Innovate in ionizable lipid chemistry. Research demonstrates that piperidine-based ionizable lipids significantly limit the production of these aldehyde impurities. LNPs formulated with these lipids have been shown to maintain mRNA activity for up to five months when stored as a liquid at 4°C, whereas formulations with other ionizable lipids lost most of their activity within two months under the same conditions [19].

Q4: During scale-up, our LNP particle size and encapsulation efficiency become inconsistent. What manufacturing factors should we control?

A4: Consistency relies on precise control over the mixing process. Manual mixing or methods with low controllability result in polydisperse nanoparticles with poor encapsulation [20]. Solution: Implement controlled mixing technologies. Microfluidics is the gold standard for research and early development, offering superior control over mixing conditions (Total Flow Rate and Flow Rate Ratio) for highly reproducible, monodisperse LNPs (PDI < 0.2) with high encapsulation efficiency (≥90%) [21] [20]. For large-scale GMP production, turbulent jet mixers offer advantages, including smaller particle size, narrow distribution, high encapsulation efficiency, and easier scalability [22].

Q5: What are the critical quality attributes (CQAs) we must monitor for LNP characterization?

A5: Key CQAs for LNP characterization and process control include [22] [20]:

- Particle Size and Polydispersity Index (PDI): Affects biodistribution and cellular uptake. Aim for a small size (e.g., 50-200 nm) and low PDI.

- Encapsulation Efficiency: The percentage of RNA successfully encapsulated within the LNPs. Crucial for therapeutic efficacy.

- Surface Charge (Zeta Potential): Influences colloidal stability and interaction with biological membranes.

- RNA Integrity: Confirms the payload has not been degraded during formulation.

- Stability: The formulation's ability to maintain its physicochemical properties over time.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessing Endosomal Damage and Inflammatory Potential

This protocol uses galectin recruitment as a biomarker for LNP-induced endosomal damage [2] [1].

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Seed appropriate cell lines (e.g., RAW 264.7 macrophages or other relevant primary cells) into glass-bottom imaging dishes.

- Transfection: Treat cells with the experimental LNPs. Include controls (e.g., untreated cells, LNPs with known low-inflammatory lipids).

- Staining: Transfect or immuno-stain for a membrane damage sensor, such as galectin-9.

- Live-Cell Imaging: Use fast live-cell or super-resolution microscopy to image cells at defined time points post-transfection (e.g., 1-6 hours).

- Quantification: Quantify the number of galectin-9-positive vesicles per cell and correlate this with the dose of LNPs internalized. A lower ratio of galectin foci to internalized LNPs indicates a less inflammatory formulation [1].

Protocol: Evaluating Lipid Thermostability and mRNA Integrity

This protocol assesses the stability of mRNA-LNP formulations during storage [19].

Methodology:

- Formulation and Storage: Prepare mRNA-LNPs using standard methods (e.g., microfluidics) and divide them into aliquots.

- Stability Challenge: Store aliquots at different temperatures (e.g., -80°C, 4°C, 25°C) for varying durations (e.g., 1 week, 1 month, 3 months).

- Analysis of Aldehyde Impurities:

- Use a fluorescence-based assay with 4-hydrazino-7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole hydrazine (NBD-H), which reacts with carbonyl compounds (aldehydes) to form fluorescent hydrazones.

- Incubate lipid samples with NBD-H and measure fluorescence; lower signals indicate fewer reactive aldehydes [19].

- Functional Potency Assay:

- Test the in vivo or in vitro efficacy of stored LNPs. For example, administer LNPs encoding a reporter protein (e.g., human erythropoietin, hEPO) to mice and measure serum protein levels via ELISA.

- Compare the functional output of fresh vs. stored LNPs to determine the rate of activity loss [19].

Data Presentation

Ionizable Lipids: Properties and Performance

Table 1: Commercially Available and Research-Grade Ionizable Lipids. This table provides a comparison of key lipids, including their pKa and noted characteristics, as cited in the literature [23] [19].

| Lipid Name | Reported pKa | Key Characteristics and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| SM-102 | ~6.68 [23] | Used in Moderna's Spikevax COVID-19 vaccine; benchmark for comparing new biodegradable lipids [23]. |

| ALC-0315 | ~6.09 [23] | Used in Pfizer/BioNTech's COVID-19 vaccine; clinically validated for strong immune responses [23]. |

| CP-LC-0729 | ~6.78 [23] | Next-generation lipid; 32-fold increase in pulmonary protein expression vs. MC3; biodegradable [23]. |

| CL15F (Piperidine-based) | 6.24 - 7.15 [19] | Research lipid; demonstrates superior thermostability, maintaining mRNA activity after 5 months at 4°C [19]. |

LNP Formulation: Core Composition and Critical Attributes

Table 2: LNP Component Functions and Target Ratios. This table summarizes the role of each key component in a standard LNP formulation [21] [20].

| LNP Component | Primary Function | Typical Molar Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipid | Encapsulates RNA via electrostatic interaction; enables endosomal escape via pH-dependent charge shift. | ~50% |

| Phospholipid (e.g., DSPC) | Provides structural integrity to the LNP bilayer; enhances stability and encapsulation efficiency. | ~10% |

| Cholesterol | Stabilizes the lipid bilayer; enhances membrane fusion and LNP stability. | ~38.5% |

| PEGylated Lipid | Shields LNP surface, improving colloidal stability, reducing aggregation, and modulating biodistribution. | ~1.5% |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

LNP Endosomal Escape and Damage Pathways

LNP Formulation and Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for LNP Research. This table lists key tools and their functions for developing and testing ionizable lipids [21] [23] [1].

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids (e.g., SM-102, ALC-0315, CP-LC-0729) | Benchmark compounds for comparing the performance of novel ionizable lipids [23]. |

| Piperidine-Based Lipid Libraries | Research lipids designed to improve thermostability and limit mRNA adduct formation [19]. |

| Fluorescently-Labeled Lipids (e.g., BODIPY-MC3) | Tracing the fate of the ionizable lipid component within cells using live-cell microscopy [1]. |

| Membrane Damage Reporters (e.g., Galectin-9) | Critical biosensors for visualizing and quantifying LNP-induced endosomal damage and inflammatory potential [2] [1]. |

| NBD-H (4-hydrazino-7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole hydrazine) | Fluorescent dye used in a microplate assay to quantify reactive aldehyde impurities in lipid formulations [19]. |

| Microfluidic Mixing Systems | Enables reproducible, scalable production of LNPs with controlled size and high encapsulation efficiency [21] [20]. |

ESCRT Pathway FAQ & Troubleshooting Guide

This technical support resource addresses common experimental challenges and questions related to the Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) pathway, with a specific focus on its role in repairing endosomal damage in lipid nanoparticle (LNP) research.

Table 1: Frequently Asked Questions about the ESCRT Pathway

| Question | Expert Answer | Key References |

|---|---|---|

| What is the primary function of the ESCRT machinery? | The ESCRT machinery performs a unique membrane remodeling and scission reaction away from the cytoplasm. It is best known for driving intralumenal vesicle formation during multivesicular body (MVB) biogenesis but is also essential for cytokinetic abscission and viral budding. | [24] [25] [26] |

| Why is the ESCRT pathway relevant to LNP-induced endosomal damage? | LNPs can cause inflammation by creating holes in the endosomal membrane during "endosomal escape." Recent research shows that if these holes are smaller, the cell can recruit the ESCRT machinery to repair them, thereby reducing inflammatory responses. | [2] |

| Which ESCRT complexes are minimal requirements for membrane scission? | ESCRT-III is considered the minimal machinery required for the final membrane scission event. Processes like HIV budding and cytokinesis can occur with only ESCRT-I, ESCRT-III, and Vps4, bypassing the need for ESCRT-0 and ESCRT-II. | [24] [27] |

| How is the ESCRT pathway linked to neurodegenerative diseases? | ESCRT dysfunction impedes the MVB pathway, disrupting membrane protein turnover. This can lead to the accumulation of toxic proteins like α-synuclein, which is implicated in Parkinson's disease. Some ESCRT-III components, such as CHMP2B, directly interact with these proteins. | [27] [28] |

| What is the role of the Vps4 ATPase? | Vps4 is a key AAA-ATPase that hydrolyzes ATP to disassemble and recycle the ESCRT-III complex from the membrane after scission is complete. This is crucial for maintaining the functionality of the entire pathway. | [24] [29] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common ESCRT Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High cytotoxicity when studying ESCRT inhibition | Non-specific or potent inhibition of ESCRT-III can block essential cellular processes like cytokinesis. | Consider using inducible or partial knockdown systems. Studies on the inhibitor retroCHMP3 show that accumulation of mutations that reduce cytotoxicity while preserving virus inhibition is possible. | [30] |

| Impaired endolysosomal degradation in ESCRT mutants | Loss of ESCRT function (e.g., Class E Vps mutants) blocks the MVB pathway, preventing cargo delivery to lysosomes. | Characterize the accumulation of aberrant prevacuolar/endosomal compartments (Class E compartments). Verify using markers for ubiquitinated cargo and late endosomes. | [24] [29] |

| Difficulty detecting transient ESCRT-III interactions | ESCRT-III subunits are transiently assembled on membranes and exist in auto-inhibited states in the cytoplasm. | Use co-immunoprecipitation or fluorescence polarization binding assays with purified recombinant proteins. Capture interactions with known partners like Vps4 or other MIT-domain containing proteins. | [24] [28] |

| Persistent α-synuclein oligomers in cellular models | α-synuclein can directly bind to ESCRT-III (e.g., CHMP2B), impeding endolysosomal function and its own degradation. | Disrupt the α-synuclein-ESCRT interaction using specific peptide inhibitors (e.g., PDpep1.3) to restore endolysosomal function and reduce oligomer levels. | [28] |

Experimental Protocols for Key ESCRT Assays

Protocol 1: Assessing ESCRT-Dependent Endosomal Repair

This protocol is adapted from recent research investigating how the ESCRT machinery repairs LNP-induced endosomal damage [2].

1. Objective: To quantify the recruitment of ESCRT proteins to damaged endosomes and correlate it with membrane repair and inflammation outcomes.

2. Key Materials:

- Galectin-3 or Galectin-8 antibody (Marker for large, irreparable membrane damage)

- Antibody against an ESCRT-III core subunit (e.g., CHMP4 / Snf7)

- Cells with knockdown/knockout of specific ESCRT components (e.g., Vps4)

- LNPs formulated with different ionizable lipids (e.g., standard vs. ESCRT-recruiting lipids)

3. Method:

- Treat cells with the LNPs of interest.

- Fix and stain cells at relevant time points post-treatment for Galectin and ESCRT-III proteins.

- Image and quantify using high-resolution confocal microscopy:

- The co-localization of ESCRT-III with damaged endosomes.

- The ratio of galectin-positive (large hole) to ESCRT-positive (small, reparable hole) endosomes.

- Correlate findings with downstream assays for inflammation (e.g., cytokine ELISA).

4. Expected Outcome: LNPs formulated with ESCRT-recruiting ionizable lipids should show higher ESCRT-III recruitment to endosomes, reduced galectin staining, and lower secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) [2].

Protocol 2: Disrupting a Pathological ESCRT Interaction with a Peptide Inhibitor

This protocol is based on a study that identified a peptide to disrupt the α-synuclein-CHMP2B interaction [28].

1. Objective: To mitigate α-synuclein-mediated cytotoxicity by disrupting its inhibitory interaction with ESCRT-III.

2. Key Materials:

- PDpep1.3 peptide (Sequence: DEEIERQLKALG) and a scrambled control peptide.

- Cell models overexpressing wild-type or mutant (A53T) α-synuclein.

- Proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG132) to induce proteostatic stress.

- Lentiviral system for peptide expression.

3. Method:

- Introduce peptides into cells via lentiviral transduction.

- Induce proteostatic stress by treating cells with MG132.

- Measure cell viability using a standard assay (e.g., MTT or CellTiter-Glo).

- Quantify α-synuclein oligomers using a protein fragment complementation assay (PCA), such as a luciferase-based PCA.

- Validate target engagement via co-immunoprecipitation to confirm disrupted α-synuclein-CHMP2B binding.

4. Expected Outcome: Cells expressing the PDpep1.3 peptide, but not the scrambled control, should show increased cell viability under stress and a significant reduction in α-synuclein oligomer levels [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying ESCRT in Membrane Repair

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Use Case | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESCRT-Recruiting LNPs | LNPs with specific ionizable lipids that create smaller, reparable holes in the endosomal membrane. | To study high mRNA delivery with minimal inflammation; as a therapeutic tool for inflammatory diseases. | [2] |

| Peptide Inhibitor (PDpep1.3) | Disrupts the pathological interaction between α-synuclein and ESCRT-III subunit CHMP2B. | To restore endolysosomal function and reduce toxic protein oligomers in Parkinson's disease models. | [28] |

| Vps4 ATPase Mutants | Expressing dominant-negative Vps4 (e.g., ATPase-deficient) blocks ESCRT-III disassembly. | To study the consequences of a "frozen" ESCRT-III state on membrane scission and repair. | [24] [29] |

| Class E Vps Mutants | Yeast or mammalian cells with mutations in ESCRT genes (e.g., Δvps27, Δvps23). | To characterize the classic "Class E compartment" phenotype and study cargo sorting defects in the MVB pathway. | [24] [29] |

| recombinant CHMP2B | Purified ESCRT-III subunit for in vitro binding studies. | Used in fluorescence polarization assays to directly measure binding affinity for peptide inhibitors. | [28] |

ESCRT-Mediated Membrane Repair Signaling Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the cellular decision-making process when an endosome is damaged, highlighting the role of the ESCRT machinery.

ESCRT-III Assembly and Disassembly Workflow

This diagram details the sequential protein interactions that govern the dynamic assembly and disassembly of the ESCRT-III complex, the core machinery for membrane scission.

Frequently Asked Questions: Core Concepts

What is the primary advantage of using BEND lipids in LNPs? The primary advantage of BEND lipids is their demonstrated ability to significantly enhance endosomal escape, which is a major bottleneck in nucleic acid delivery. Their unique terminally branched structure increases the delivery efficiency of mRNA and CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes, leading to higher transfection and gene editing efficacy, in some cases by as much as tenfold compared to linear lipids used in commercial COVID-19 vaccines [31] [32].

How does the structure of BEND lipids contribute to reduced cellular damage? While the core BEND lipid study focuses on delivery efficacy, broader LNP research indicates that the nature of endosomal disruption is critical for damage. One strategy involves using ionizable lipids that create smaller, repairable holes in the endosomal membrane. These smaller holes allow for cargo release while enabling the cell to recruit the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) machinery to repair the damage. This repair process prevents large, irreparable ruptures that expose glycans to the cytosol and are detected by galectin proteins, which trigger inflammatory pathways [2]. BEND lipids' branched architecture may allow for finer control over the type of membrane disruption, potentially aligning with this less-damaging mechanism.

For which applications have BEND lipids shown particular promise? BEND lipids have shown high performance in several advanced therapeutic applications, including [33] [34]:

- Hepatic gene editing: Efficient delivery of mRNA and CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes to the liver for therapeutic gene editing.

- T cell engineering: Enhanced transfection of hard-to-transfect T cells, which is crucial for CAR-T cell and other immunotherapies.

Troubleshooting Guides: Experimental Design & Optimization

Challenge: Low Endosomal Escape and Transfection Efficiency

| Potential Cause | Proposed Solution | Key Experimental Parameters to Monitor |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal branching type or location | Ensure lipid synthesis creates terminal branching (at the end of the lipid tail) rather than branching near the amine headgroup. Test different branched caps (e.g., isopropyl, tert-butyl, sec-butyl) [33]. | • Transfection efficiency (e.g., luminescence from FLuc mRNA) [33]• Gene editing rate (e.g., % of cells with successful edits) [33] |

| Inefficient LNP formulation | Standardize LNP formulation using a herringbone microfluidic device. Use a consistent molar ratio of lipid components (e.g., 35:16:46.5:2.5 for IL/DOPE/Cholesterol/C14-PEG2000) to isolate the effect of the ionizable lipid structure [33]. | • LNP size and PDI (e.g., DLS to target 70-160 nm with PDI ~0.2) [33]• Encapsulation efficiency (should be >80%) [33]• pKa (should be ~6.0 for efficient endosomal escape) [33] |

| Insufficient understanding of structure-activity relationship (SAR) | Systematically vary the lipid tail length and branching pattern while keeping the amine core constant to establish robust SARs. Even minor structural changes can have substantial impacts on delivery efficacy [35]. | • In vivo protein expression (e.g., luciferase expression in target tissues like the liver) [35] |

Challenge: Managing LNP-Induced Inflammation and Cytotoxicity

| Potential Cause | Proposed Solution | Key Experimental Parameters to Monitor |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive endosomal membrane damage | Explore ionizable lipid designs that create smaller, ESCRT-repairable holes in the endosome. Inhibiting galectin-3 can also abrogate inflammation from existing LNP formulations, but engineering less-damaging lipids is a superior long-term strategy [2]. | • Cytokine secretion (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) in cell culture supernatants or animal models (e.g., BAL fluid) [2]• Cell viability assays (e.g., MTT, LDH release) [16] |

| Fast kinetics of endosomal disruption | Research indicates that the rate of endosomal disruption correlates with cytotoxicity. Slower, more controlled disruption may improve safety profiles. The branched architecture of BEND lipids may offer a handle to tune this kinetic parameter [16]. | • Kinetics of endosomal damage (e.g., using galectin recruitment as a proxy for large, irreparable damage) [2]• High-content imaging to correlate LNP uptake with toxicity markers [16] |

| Lipid accumulation from slow degradation | Consider incorporating biodegradable chemical motifs, such as ester bonds, into the lipid tails. This promotes rapid clearance and reduces the risk of long-term toxicity, which is especially important for therapies requiring repeat dosing [16]. | • Lipid clearance rates in pharmacokinetic studies [16] |

Experimental Data and Protocols

Key Quantitative Findings on BEND Lipid Performance

The following table summarizes critical data from the foundational BEND lipid study, providing benchmarks for your own experiments [33].

| Lipid Structure (Example) | Branching Type | mRNA Delivery Efficiency (Relative to Linear Lipids) | Gene Editing Efficiency | Key Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E8i-494 | Isopropyl | Up to 10-fold increase in vitro | Significantly enhanced | Effective for hepatic delivery and T cell engineering [33]. |

| E12t-494 | tert-Butyl | Up to 10-fold increase in vitro | Significantly enhanced | Improved endosomal disruption due to conical shape [33]. |

| E8s-494 | sec-Butyl | Up to 10-fold increase in vitro | Significantly enhanced | Demonstrates the importance of branching stereochemistry [33]. |

| Linear Control (e.g., MC3) | None | Baseline | Baseline | Benchmark against established ionizable lipids [33]. |

Detailed Protocol: Synthesizing and Testing BEND Lipids

This protocol is adapted from the methods used in the primary research [33].

Synthesis of Branched Epoxides:

- Step 1 (C-C Coupling): Couple a primary bromoalkene with a commercially available branched Grignard cap (e.g., isopropyl, tert-butyl) via a copper-catalyzed Grignard reaction to produce a branched alkene. For longer chains, synthesize the primary bromoalkene first from a terminal dibromoalkane using a mono E2 reaction with tert-butoxide.

- Step 2 (Epoxidation): Convert the branched alkene into the corresponding branched epoxide using m-chloroperbenzoic acid (mCPBA). These two steps can be completed in less than 24 hours.

Synthesis of BEND Ionizable Lipids (ILs):

- React the branched epoxide with a polyamine core (e.g., 494: 2-(2-aminoethoxy)-N-(2-(4-(2-(2-aminoethoxy)ethyl)piperazin-1-yl)ethyl)ethan-1-amine) via an SN2 reaction to form the final BEND IL.

Formulation of LNPs:

- Use a herringbone microfluidic device to formulate LNPs at a standard molar ratio of 35:16:46.5:2.5 (IL:DOPE:Cholesterol:C14-PEG2000).

- Encapsulate mRNA at a 10:1 weight ratio (IL:mRNA).

LNP Characterization:

- Size and PDI: Measure via Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). Target: 70-160 nm, PDI ~0.2.

- Encapsulation Efficiency: Use a Ribogreen assay. Target: >80%.

- pKa: Determine via TNS fluorescence assay. Target: ~6.0.

Functional Testing:

- In vitro Transfection: Incubate LNPs (e.g., dose of 20 ng FLuc mRNA/20,000 cells) with target cells (e.g., HeLa, T cells) for 24 hours and measure luminescence.

- In vivo Efficacy: Administer LNPs to animal models (e.g., via intravenous injection for liver targeting). Quantify protein expression (luciferase) or gene editing efficiency in target tissues.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in BEND Lipid Research |

|---|---|

| Primary Bromoalkenes | Establishes the length of the lipid tail in the synthetic scheme [33]. |

| Branched Grignard Caps (e.g., isopropyl, tert-butyl) | Introduces the key terminal branching group to the lipid structure [33]. |

| Polyamine Core 494 | Common amine core used to create ionizable lipids with a proven track record in various delivery applications [33]. |

| Helper Lipids (DOPE, Cholesterol, C14-PEG2000) | DOPE: Promotes non-bilayer structures that aid endosomal escape. Cholesterol: Stabilizes the LNP membrane. PEG-lipid: Reduces aggregation and controls particle size [33]. |