Photon Avalanching Nanoparticles: The Foundation for Next-Generation Optical Computing

This article explores the groundbreaking development of photon avalanching nanoparticles (ANPs) as a transformative material for optical computing.

Photon Avalanching Nanoparticles: The Foundation for Next-Generation Optical Computing

Abstract

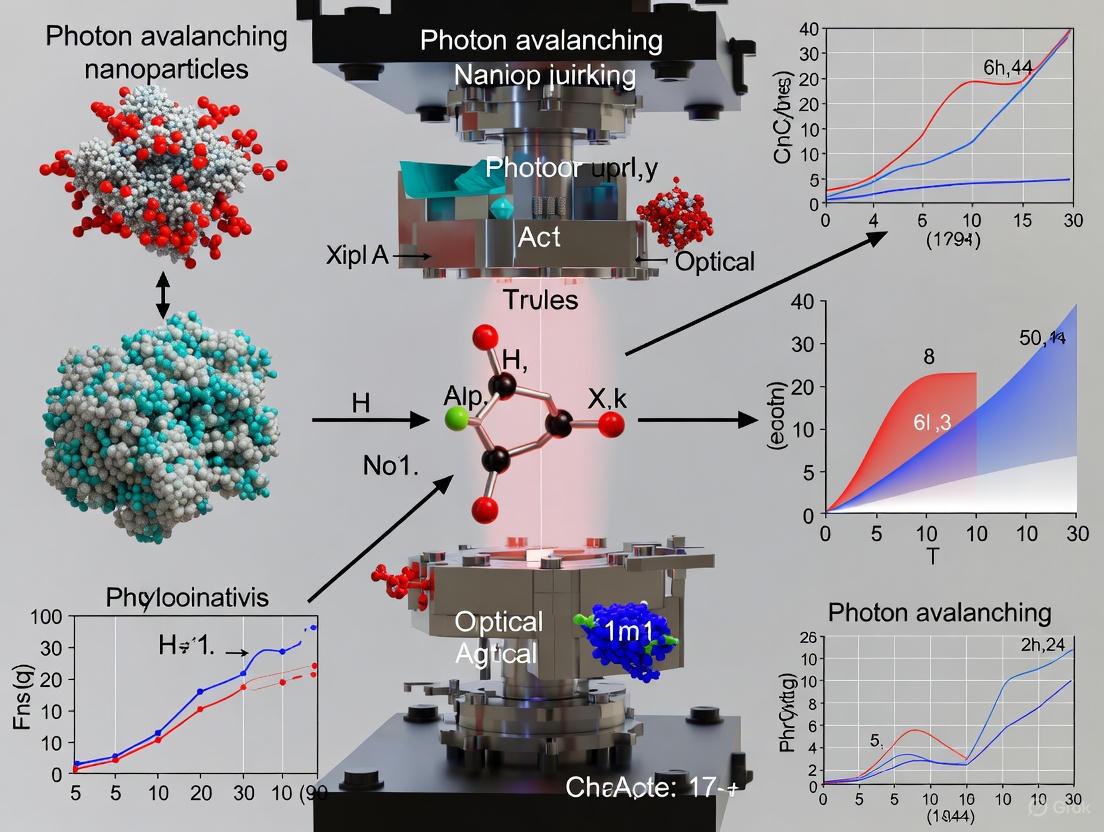

This article explores the groundbreaking development of photon avalanching nanoparticles (ANPs) as a transformative material for optical computing. Aimed at researchers and scientists, we detail the foundational principle of intrinsic optical bistability (IOB) recently demonstrated in nanoscale materials, a critical advancement for creating optical memory and transistors. The content covers the synthesis and mechanism of these neodymium-doped nanoparticles, their application in nanoscale optical components, the current challenges in material optimization and environmental stability, and a comparative analysis validating their unprecedented nonlinear performance against existing technologies. This synthesis provides a comprehensive roadmap for leveraging ANPs to overcome the limitations of traditional electronics and enable faster, more energy-efficient computing paradigms.

Unlocking the Mechanism: The Science Behind Photon Avalanching and Intrinsic Optical Bistability

Abstract Photon Avalanching (PA) is a distinctive optical phenomenon characterized by a highly nonlinear emission process, where a minute increase in pump power results in a disproportionate, massive surge in light output. This guide details the core principles, quantitative metrics, and experimental methodologies of PA, with a specific focus on its recent realization in lanthanide-doped nanoparticles. The emergence of intrinsic optical bistability in these nanomaterials, driven by PA's extreme nonlinearity, positions them as foundational components for next-generation optical computing, enabling the development of nanoscale optical memory, transistors, and logic gates.

Photon Avalanching (PA) is a quantum optical process that produces steep, nonlinear dynamics, enabling the generation of high-energy photons from low-power, continuous-wave excitation [1] [2]. It is defined by a positive feedback loop that couples ground-state absorption (GSA), excited-state absorption (ESA), and cross-relaxation (CR) between luminescent ions [3]. Once a critical excitation threshold is surpassed, the system enters a chain-reaction state, leading to an exponential growth in the population of excited ions and a consequent avalanche of emitted light.

The transition of PA from a curiosity observed in bulk crystals to a controllable phenomenon in single nanostructures marks a pivotal advancement [1] [2]. This guide delineates the PA mechanism, its quantitative benchmarks, and the experimental protocols for its observation, framing this discussion within the pursuit of advanced photonic technologies, particularly optical computing.

Fundamental Mechanism and Signaling Pathways

The PA mechanism is a cyclic process that relies on specific energy transitions within lanthanide ions (e.g., Tm³⁺, Nd³⁺) embedded in a crystalline host. The process can be broken down into a series of key steps, as illustrated in the following diagram and described thereafter.

Diagram 1: The Photon Avalanching (PA) Mechanism Feedback Loop.

- Initial (Weak) Ground-State Absorption (GSA): A single ion absorbs a photon through a weak, non-resonant GSA transition, populating an intermediate energy state. The GSA is intentionally weak, as the excitation laser energy is chosen to be resonant with an ESA transition, not a ground-state one [1] [3].

- Excited-State Absorption (ESA): The excited ion absorbs a second photon, promoting it to a higher-energy state. A defining characteristic of PA is that the cross-section for ESA is tremendously larger (by a factor of >10,000) than that for GSA [1] [2].

- Cross-Relaxation (CR): The highly excited ion transfers part of its energy to a nearby neighboring ion in the ground state via a non-radiative CR process. This results in two ions populating the intermediate excited state [3] [4].

- Positive Feedback Loop: The two excited ions are now primed to undergo ESA again, leading to four excited ions after the next CR cycle. This looping process creates a nonlinear, exponential growth in the population of the intermediate state, a phenomenon akin to a chain reaction [2] [3].

- Avalanche Emission: The massive buildup of excited ions leads to intense, high-energy (e.g., ultraviolet or visible) photon emission through radiative decay, even when pumped with low-energy (e.g., near-infrared) photons [1].

Quantitative Definition and Performance Metrics

The extreme nonlinearity of PA is quantitatively defined by its power dependence and dynamic temporal response.

3.1 Power Dependence and Nonlinearity The emission intensity ((I{em})) scales with the pump power ((P{pump})) according to a power law: (I{em} \propto P{pump}^n), where (n) is the nonlinearity order. PA is characterized by very high (n) values, often exceeding 20 and reaching up to 200 or more in optimized systems [1] [5]. This means a doubling of pump power can cause an emission increase by a factor of thousands or millions.

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics of Photon Avalanching in Selected Systems

| Material System | Dopant Ion(s) | Excitation Wavelength | Nonlinearity Order (n) | Key Identifying Feature | Primary Application Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaYF₄ Nanoparticle [1] | Tm³⁺ | 1064 nm or 1450 nm | ~26 | Clear threshold, prolonged rise time | Super-resolution imaging |

| KPb₂Cl₅ Nanocrystal [5] | Nd³⁺ | 1064 nm | >200 | Intrinsic optical bistability (IOB) | Optical memory & switching |

| NaLuF₄-based Nanoparticle [2] | Tm³⁺ | 1450 nm | ~150 | Lattice contraction enhancing CR | High-nonlinearity for sensing |

3.2 Key Identifying Hallmarks Beyond high nonlinearity, PA is identified by three operational hallmarks [2] [3]:

- Clear Excitation-Power Threshold ((I_{th})): Emission remains low until a specific pump intensity is reached, after which it surges dramatically.

- Prolonged Rise Time: Near the threshold, the time for emission to reach its maximum ("rise time") extends significantly, from microseconds to tens or hundreds of milliseconds, due to "critical slowing down" of the population dynamics [1] [2].

- Dominant ESA over GSA: The ratio of the ESA to GSA cross-section typically exceeds 10,000, ensuring the feedback loop is efficient [1].

Experimental Protocols for PA Observation

This section provides a generalized workflow for conducting and analyzing a PA experiment, crucial for validating the phenomenon in new material systems.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Photon Avalanching Observation.

4.1 Power-Dependent Luminescence Measurement

- Objective: To determine the nonlinearity order ((n)) and identify the avalanche threshold ((I_{th})).

- Protocol:

- Excitation: Irradiate the ANP sample with a continuous-wave (CW) laser at a wavelength resonant with the ESA transition (e.g., 1450 nm for Tm³⁺) [1].

- Power Ramp: Systematically increase the pump power over a defined range, typically spanning several orders of magnitude.

- Detection: At each power step, record the integrated intensity of the upconverted emission (e.g., ~800 nm for Tm³⁺) using a spectrometer or a photodetector.

- Analysis: Plot the logarithm of the emission intensity against the logarithm of the pump power. The slope of the linear region above the threshold provides the nonlinearity order (n). The threshold (I_{th}) is identified as the point of inflection in the S-shaped curve [1] [3].

4.2 Time-Resolved Rise Time Measurement

- Objective: To observe the characteristic prolonged rise time, a key signature distinguishing PA from other upconversion mechanisms.

- Protocol:

- Excitation Setup: Set the pump laser power to a value slightly above the identified threshold (I_{th}).

- Pulsed Excitation: Use an optical shutter or a pulsed laser to deliver a square-wave excitation pulse to the sample.

- Signal Acquisition: Use a fast detector (e.g., photomultiplier tube) connected to an oscilloscope to record the temporal profile of the emission signal as it rises from zero to its steady-state maximum.

- Analysis: The rise time is measured as the time taken for the signal to go from 10% to 90% of its maximum. A pronounced elongation of this rise time (to milliseconds or longer) near the threshold confirms the PA mechanism [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The reliable observation of PA requires careful selection and synthesis of nanomaterials and excitation sources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for PA Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Critical Parameters & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Host Lattice | Inorganic crystal matrix for dopant ions. Governs phonon energy and stability. | Low Phonon Energy Hosts (e.g., NaYF₄, NaGdF₄, KPb₂Cl₅) are essential to minimize non-radiative losses [2] [3]. |

| Dopant Ions | Trivalent lanthanide ions that undergo the PA process. | Tm³⁺, Nd³⁺ are common activators. High doping concentrations ( several mol%) are required to facilitate efficient CR [1] [5]. |

| Inert Shell | A protective, undoped layer grown epitaxially around the ANP core. | Mitigates surface quenching, significantly reducing the avalanche threshold and enhancing brightness [2]. |

| NIR Laser Source | Continuous-wave laser for excitation. | Wavelength must target the ESA transition, not GSA (e.g., 1064 nm or 1450 nm for Tm³⁺; 1064 nm for Nd³⁺) [1] [5]. |

| Confocal Microscope | Primary instrument for single-particle spectroscopy. | Enables spatial isolation of single ANPs and measurement of their nonlinear properties, free from ensemble averaging effects [1]. |

Photon Avalanching in Optical Computing

The extreme nonlinearity of PA nanoparticles directly enables critical functions for optical computing. A paramount recent advancement is the demonstration of Intrinsic Optical Bistability (IOB) in Nd³⁺-doped avalanching nanocrystals [5]. In an IOB state, the ANP can exist in one of two stable emission states ("on" or "off") based on its excitation history, a property that is non-thermal and stems directly from the PA feedback loop [6] [5].

This IOB behavior manifests as a hysteresis loop in the input-output power relationship:

- Optical Memory: The ANP remains brightly luminescent even when the pump power is reduced below the initial switching threshold, only turning "off" at a much lower power. This allows the nanoparticle to function as a nanoscale optical memory bit, with its state controlled by the history of the light input [7] [5].

- Optical Transistor: The emission from one ANP (the source) can be used to control the state of a second, nearby ANP (the drain), effectively creating a transistor-like optical switch that uses light to manipulate light [5].

These capabilities establish PA nanomaterials as promising building blocks for all-optical logic gates, volatile memory, and neuromorphic computing architectures, potentially operating at sizes comparable to modern microelectronics but with the speed and parallelism of photonics [2] [6].

Photon Avalanching is a rigorously definable optical phenomenon whose transition to the nanoscale has unlocked a new paradigm in nonlinear optics. Its hallmark extreme nonlinearity, clear excitation threshold, and prolonged rise dynamics are measurable through standardized experimental protocols. The recent discovery of IOB in these materials, underpinned by a non-thermal, PA-driven mechanism, provides a direct pathway to harnessing this unique physical process for revolutionary computational technologies. As material synthesis and hybrid integration techniques advance, photon avalanching nanoparticles are poised to form the core of compact, fast, and highly efficient optical computing systems.

The Discovery of Intrinsic Optical Bistability (IOB) in Nanoscale Materials

Intrinsic optical bistability (IOB) represents a fundamental photonic phenomenon where a material can exist in one of two distinct optical states under identical excitation conditions, with the state determination dependent on the system's excitation history [8] [5]. This memory effect enables materials to function as optical switches or memory elements, where light can be used to control light itself. For decades, IOB remained primarily confined to bulk materials systems, which posed significant limitations for integration into modern photonic devices and chip-scale technologies [9] [10]. The recent demonstration of IOB in photon avalanching nanoparticles (ANPs) marks a transformative advancement, bridging the critical gap between functional optical phenomena and practical nanoscale photonic applications [8] [5].

Photon avalanching (PA) is an unconventional upconversion mechanism characterized by an extreme nonlinear optical response, where minute increases in excitation power trigger disproportionate surges in luminescence output—often exceeding 10,000-fold intensity enhancements from a mere doubling of pump power [2] [9]. This phenomenon emerges from a positive feedback loop combining weak ground-state absorption (GSA), resonant excited-state absorption (ESA), and highly efficient cross-relaxation (CR) energy transfer between neighboring lanthanide ions [2] [3]. The PA cycle initiates when a single ion in the intermediate energy state absorbs a photon via ESA to reach a higher excited state, then transfers part of its energy to a nearby ground-state ion via CR, resulting in two ions in the intermediate state—each capable of perpetuating the cycle [2] [3]. This chain reaction produces a nonlinearity orders of magnitude greater than conventional multiphoton processes, enabling the observed bistable behavior when engineered within appropriate host materials [8] [5].

The convergence of IOB with photon avalanching at the nanoscale establishes a new paradigm for photonic device engineering, offering a pathway to optical memory and transistors with feature sizes comparable to contemporary electronic components [8] [9] [10]. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, experimental methodologies, and application landscapes for IOB-enabled photon avalanching nanomaterials, contextualized within the broader framework of optical computing research.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Photon Avalanching Mechanism

The photon avalanching process operates through a precisely coordinated interplay of three fundamental processes: non-resonant ground-state absorption (GSA), resonant excited-state absorption (ESA), and cross-relaxation (CR) energy transfer [2] [3]. These components form a positive feedback loop that enables the characteristic extreme nonlinearity of PA systems.

Table 1: Key Processes in Photon Avalanching

| Process | Description | Function in PA Feedback Loop |

|---|---|---|

| Ground-State Absorption (GSA) | Weak, non-resonant absorption of pump photons | Initial population of intermediate state; rate-limiting step |

| Excited-State Absorption (ESA) | Resonant absorption from intermediate to higher excited state | Enables energy accumulation in individual ions |

| Cross-Relaxation (CR) | Energy transfer creating two ions in intermediate state from one excited ion | Population multiplication mechanism; drives nonlinearity |

The PA process initiates when a minimal number of ions reach an intermediate excited state through the weak, non-resonant GSA process. Once in this intermediate state, these ions can efficiently absorb additional pump photons through resonant ESA, promoting them to higher energy levels. Subsequently, these highly excited ions undergo CR energy transfer with nearby ground-state ions, resulting in two ions in the intermediate excited state—effectively doubling the population capable of continuing the cycle [2] [3]. This exponential growth in the excited-state population continues until saturation or system limitations intervene, producing the characteristic avalanche effect.

The exceptional nonlinearity of PA stems from the requirement for a significant ESA-to-GSA cross-section ratio, typically exceeding 10,000:1, ensuring that absorption occurs predominantly from excited states rather than ground states [2]. This large ratio creates a system where the emission intensity (I) depends on the pump power (P) raised to an extremely high power (I ∝ P^k), with reported nonlinearity orders (k) reaching >200 in recent IOB-enabled nanomaterials [8] [5].

Intrinsic Optical Bistability Emergence

Intrinsic optical bistability emerges naturally from the extreme nonlinearity of photon avalanching when combined with specific material properties that suppress non-radiative decay pathways [8] [5]. The bistability manifests as a hysteresis loop in the input-output relationship, where the system maintains either a high-emission ("on") or low-emission ("off") state under identical intermediate excitation powers, with the current state determined by the excitation history [8] [9] [10].

The underlying mechanism for IOB in avalanching nanoparticles involves a non-thermal feedback process fundamentally distinct from earlier explanations based on laser-induced heating [5] [9]. Recent studies identify that IOB originates from the interplay between the positive feedback of photon avalanching and suppressed non-radiative relaxation in specific host matrices [8] [5]. In neodymium-doped potassium lead chloride (KPb₂Cl₅) nanoparticles, the host lattice's low phonon energy dampens vibrational modes that typically facilitate non-radiative decay, thereby enhancing the population buildup in the intermediate state and stabilizing both the on and off states under appropriate excitation conditions [5].

The following diagram illustrates the coupled photon avalanching and bistability mechanisms:

Diagram 1: Photon Avalanching and Bistability Mechanism

The hysteresis behavior emerges because the "on" state, once established, can be maintained at lower pump powers than required for initial activation due to the self-sustaining nature of the avalanching process [8] [5]. Conversely, the system only transitions to the "off" state when pump power drops below a critical threshold where the avalanching can no longer be sustained [5] [9]. This creates the memory effect essential for optical memory applications, as the nanoparticle's emission state preserves information about previous excitation conditions.

Experimental Realization and Protocols

Nanomaterial Synthesis and Composition

The successful demonstration of IOB in nanoscale materials utilized specifically engineered neodymium-doped potassium lead chloride (KPb₂Cl₅:Nd³⁺) nanoparticles with controlled size and dopant distribution [8] [5]. The synthesis protocol involves:

- Precursor Preparation: Combining lead chloride (PbCl₂) and potassium chloride (KCl) precursors in stoichiometric ratios with neodymium(III) chloride (NdCl₃) as the dopant source, typically achieving Nd³⁺ concentrations of 1-5% [5].

- Nanoparticle Synthesis: Executing a hot-injection colloidal synthesis at temperatures between 150-200°C under inert atmosphere to produce monodisperse nanoparticles with approximate 30nm diameter [8] [5] [9].

- Surface Passivation: Implementing ligand exchange protocols to enhance dispersibility and environmental stability while maintaining optical properties [5].

The selection of KPb₂Cl₅ as a host matrix proves critical due to its exceptionally low phonon energy (~200 cm⁻¹), which significantly suppresses non-radiative decay pathways that would otherwise quench the avalanching process [5]. This host material enables the long intermediate-state lifetime essential for establishing the positive feedback loop while minimizing parasitic losses [8] [5].

Table 2: Key Material Properties for IOB in Avalanching Nanoparticles

| Parameter | Specification | Impact on IOB Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Host Material | KPb₂Cl₅ (potassium lead chloride) | Provides low phonon energy for suppressed non-radiative decay |

| Dopant Ion | Nd³⁺ (neodymium) | Avalanche-active ion with appropriate energy level structure |

| Particle Size | 30 nm | Optimizes confinement effects while maintaining avalanching efficiency |

| Dopant Concentration | 1-5% | Balances cross-relaxation efficiency against concentration quenching |

| Phonon Energy | <300 cm⁻¹ | Minimizes non-radiative losses; enhances excited-state lifetimes |

Optical Characterization Methodology

The experimental protocol for verifying IOB in avalanching nanoparticles requires specific optical characterization techniques to distinguish genuine bistability from other nonlinear phenomena:

- Power-Dependent Luminescence: Measuring emission intensity as a function of increasing and decreasing excitation power using a continuous-wave (CW) infrared laser (typically 1064 nm) to identify the characteristic S-shaped response curve and hysteresis loop [5].

- Rise-Time Measurements: Characterizing luminescence rise times at various excitation powers, with PA systems exhibiting prolonged rise times (tens to hundreds of milliseconds) near the threshold due to critical slowing dynamics [2] [3].

- Hysteresis Loop Mapping: Quantifying the width and shape of hysteresis loops by modulating laser power with precise control over pulse duration and repetition rates [5].

- Dual-Laser Switching Experiments: Demonstrating transistor-like optical switching using a second laser beam to control the emission state, establishing potential for all-optical circuits [5] [11].

The experimental workflow for characterizing IOB follows a systematic approach to establish the non-thermal origin of the bistability and quantify key performance parameters:

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for IOB Characterization

Critical to these experiments is the exclusion of thermal effects as the bistability mechanism. Researchers employed computer modeling and temperature-control measurements to confirm that the observed IOB originates from the intrinsic avalanching dynamics rather than laser-induced heating [5] [9]. This distinction represents a significant advancement over previous reports of nanoscale optical bistability, where thermal effects often dominated the switching behavior [8] [10].

Quantitative Performance Data

The exceptional performance of IOB-enabled photon avalanching nanoparticles emerges from their unprecedented optical nonlinearities and well-defined bistable characteristics. Systematic quantification of these parameters provides insights into their potential for practical photonic applications.

Table 3: Quantitative Performance Metrics of IOB Nanoparticles

| Performance Parameter | Reported Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Nonlinearity Order | >200 [8] [5] | Extreme sensitivity to excitation power changes |

| Emission Intensity Increase | 10,000-fold from doubled pump power [9] [10] | Enables high-contrast switching between states |

| Hysteresis Width | Tunable via laser pulsing modulation [5] | Determines operational range for memory applications |

| Particle Size | 30 nm [8] [5] [9] | Compatibility with current microelectronics feature sizes |

| Rise Time | Prolonged near threshold (characteristic of PA) [2] [3] | Distinguishes PA from other upconversion mechanisms |

| Switching Cycles | >1,000 without degradation [2] | Demonstrates robustness for practical devices |

The extreme nonlinearity observed in these systems—where doubling the excitation power produces a 10,000-fold increase in emission intensity—represents the highest nonlinearity ever reported in any material system [9] [10]. This exceptional response enables the clear separation between "on" and "off" states essential for reliable binary operations in computing applications.

The hysteresis characteristics prove particularly significant for memory applications, as the large difference between activation and deactivation thresholds creates a broad intermediate power range where the nanoparticle's state (bright or dark) depends exclusively on its excitation history [8] [5]. This history-dependent behavior embodies the essential memory property required for optical random-access memory (RAM) elements [8] [9]. Furthermore, the tunability of hysteresis width through laser pulsing parameters provides additional flexibility for optimizing device performance for specific applications [5].

Applications in Optical Computing and Photonics

Optical Memory and Switching

The intrinsic optical bistability demonstrated in photon avalanching nanoparticles enables several transformative applications in optical computing, particularly for optical memory elements and all-optical switching components:

Volatile Optical Memory: The bistable emission states (bright/dark) under intermediate excitation powers serve as the foundation for optical random-access memory (RAM), where the state can be written and read optically without altering material properties [8] [9] [10]. The volatility characteristics resemble electronic RAM, with state retention dependent on sustained intermediate-power excitation.

Optical Transistors: The demonstration of transistor-like optical switching using dual-laser excitation establishes the potential for cascadable optical logic elements, where one light beam controls the state of another [5] [11]. This functionality enables the construction of all-optical logic gates without intermediate electronic conversion.

Programmable Photonic Circuits: The compatibility of these nanomaterials with direct lithography patterning techniques enables integration into complex photonic circuits, potentially allowing 3D volumetric interconnects that surpass the planar constraints of electronic integrated circuits [12].

Neuromorphic Computing and Advanced Applications

Beyond conventional computing paradigms, IOB nanoparticles exhibit properties conducive to neuromorphic computing approaches that mimic biological neural processing:

- Photonic Synapses: The temporal dynamics of photon avalanching, including paired-pulse facilitation and short-term plasticity, resemble key characteristics of biological synapses, enabling artificial neural networks that operate directly in the optical domain [13].

- Reservoir Computing: The history-dependent response and nonlinear transformation of input signals make PA systems suitable for reservoir computing frameworks, where the material itself performs complex computations on time-varying optical inputs [13].

- Pattern Recognition: The integration of PA nanoparticles with simple artificial neural networks has demonstrated capability for machine-learning-algorithm-free feature extraction and pattern recognition, potentially bypassing energy-intensive digital computation for specialized tasks [13].

The following diagram illustrates the application ecosystem for IOB-enabled nanoparticles in advanced computing systems:

Diagram 3: IOB Nanoparticle Computing Applications

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful experimental investigation of intrinsic optical bistability in photon avalanching nanoparticles requires specific material systems, optical components, and characterization tools. The following table details essential research reagents and their functions in studying IOB phenomena.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for IOB Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Host Materials | Potassium lead chloride (KPb₂Cl₅), Sodium yttrium fluoride (NaYF₄) [2] [5] | Low-phonon-energy matrices that suppress non-radiative decay |

| Dopant Ions | Neodymium (Nd³⁺), Thulium (Tm³⁺), Praseodymium (Pr³⁺) [2] [3] | Avalanche-active lanthanides with appropriate energy level structures |

| Excitation Sources | Continuous-wave infrared lasers (1064 nm, 1450 nm) [2] [5] | Resonant with excited-state absorption transitions |

| Detection Systems | Time-resolved single-photon counting modules, Spectrometers with NIR sensitivity [5] [3] | Capture nonlinear emission kinetics and power dependence |

| Synthesis Precursors | Lead chloride (PbCl₂), Potassium chloride (KCl), Neodymium(III) chloride (NdCl₃) [5] | Nanoparticle synthesis with controlled stoichiometry |

| Stabilization Ligands | Oleic acid, Oleylamine [5] | Surface passivation for improved dispersibility and stability |

The selection of appropriate host materials proves particularly critical, with heavy halide hosts like KPb₂Cl₅ offering superior performance due to their exceptionally low phonon energies compared to more conventional fluoride hosts [5]. This characteristic directly enhances the avalanching efficiency by minimizing multiphonon relaxation rates, thereby enabling the population buildup essential for the feedback mechanism [5].

Similarly, the choice of dopant ions significantly influences the avalanching characteristics, with Nd³⁺ emerging as a particularly favorable option in KPb₂Cl₅ hosts due to its appropriate energy level structure that facilitates efficient cross-relaxation while minimizing competing decay pathways [5]. The specific neodymium energy levels in this host enable the precise resonance conditions required for the ESA-to-GSA cross-section ratio essential for avalanche initiation [5].

Future Research Directions and Challenges

Despite the significant advances represented by the demonstration of IOB in photon avalanching nanoparticles, several challenges remain before widespread technological implementation becomes feasible:

- Environmental Stability: The current material systems, particularly potassium lead chloride hosts, exhibit sensitivity to moisture and environmental degradation, necessitating the development of protective coating strategies or alternative host materials with comparable optical properties but improved stability [5] [12].

- Integration Protocols: Methods for reliable integration of IOB nanoparticles into photonic circuits require further development, including addressing compatibility with existing semiconductor fabrication processes and establishing standardized interconnection strategies [2] [12].

- Performance Optimization: Trade-offs between nonlinearity strength, switching speed, and operational thresholds present complex optimization challenges that may benefit from machine-learning-assisted materials design and high-throughput screening approaches [2] [3].

- Temperature Sensitivity: While the IOB mechanism is non-thermal, temperature variations can influence performance metrics, potentially requiring stabilization strategies for practical applications across varying environmental conditions [3].

Promising research directions include exploring new host materials with even lower phonon energies, developing heterostructured nanoparticles with spatially optimized dopant distributions, and investigating co-doping strategies to engineer specific performance characteristics [2] [3]. The integration of IOB nanoparticles with photonic cavities and waveguides also presents opportunities for enhancing light-matter interaction and reducing operational power requirements [2].

Furthermore, the application of data-driven materials discovery approaches, combining machine learning with high-throughput synthesis and characterization, may accelerate the identification of novel material compositions with enhanced IOB performance [2] [3]. These efforts will likely focus on optimizing the complex interplay between host matrix properties, dopant concentrations, and nanoparticle morphology to achieve tailored bistable characteristics for specific computing applications.

The discovery of intrinsic optical bistability in photon avalanching nanoparticles represents a landmark achievement in nanophotonics, effectively bridging the long-standing gap between fundamental optical phenomena and practical nanoscale photonic devices. The extreme optical nonlinearities (>200th-order) and robust bistable switching demonstrated in neodymium-doped KPb₂Cl₅ nanoparticles establish a new paradigm for all-optical information processing at the nanoscale [8] [5].

This technological breakthrough paves the way for the development of optical memory and transistors with feature sizes comparable to contemporary electronic components, potentially enabling the next generation of computing systems that leverage light instead of electricity for fundamental operations [8] [9] [10]. The non-thermal mechanism underlying this IOB effect, arising from the synergistic combination of photon avalanching dynamics and suppressed non-radiative relaxation in low-phonon-energy hosts, provides a reliable foundation for device engineering without the efficiency limitations of thermally mediated switching [5] [9].

As research progresses toward addressing stability and integration challenges, IOB-enabled photon avalanching nanoparticles are positioned to catalyze transformative advances across multiple domains, including optical computing, neuromorphic engineering, and integrated photonics. The continued refinement of these material systems and their incorporation into functional device architectures promises to unlock new computational paradigms that exploit the unique capabilities of light as both information carrier and processing medium.

Photon avalanching nanoparticles (ANPs) represent a groundbreaking class of materials exhibiting extreme optical nonlinearity, where minute increases in pump power trigger disproportionate surges in emission intensity. This phenomenon, characterized by nonlinearity coefficients reaching 70 or higher, enables revolutionary applications in super-resolution imaging, sensitive detection, and optical computing. The recent discovery of photon avalanche behavior in neodymium-doped potassium-lead-halide nanocrystals marks a significant advancement, as these materials combine unprecedented nonlinear performance with nanoscale dimensions compatible with modern photonic integration. These nanoparticles demonstrate the highest optical nonlinearities ever observed in any material, making them particularly promising for developing optical memory and transistors at the nanometer scale—key components for next-generation optical computers that leverage light instead of electricity for information processing.

The unique properties of potassium-lead-halide hosts stem from their exceptionally low phonon energies, which minimize non-radiative energy losses and promote efficient nonlinear processes. When doped with neodymium ions (Nd³⁺), these nanocrystals facilitate a photon avalanche mechanism driven by a positive feedback loop combining weak ground-state absorption, resonant excited-state absorption, and highly efficient cross-relaxation energy transfer between neighboring Nd³⁺ ions. This review comprehensively examines the core material composition of Nd³⁺-doped potassium-lead-halide nanocrystals, detailing their synthesis, structural properties, optical characteristics, and specific applications in optical computing research, with particular emphasis on experimental protocols and quantitative performance metrics essential for research implementation.

Material Composition and Structural Properties

Host Matrix Characteristics

The potassium-lead-halide host matrix, specifically in the form of KPb₂X₅ (where X = Cl, Br), provides an exceptional foundation for photon avalanching phenomena due to its unique structural and vibrational properties. These materials feature tunable phonon energies as low as 128 cm⁻¹, achieved through precise control of halide composition and nanocrystal size [14]. This ultra-low phonon energy is critical for minimizing non-radiative decay pathways and promoting higher excited state populations necessary for avalanche processes. The KPb₂Cl₅ variant demonstrates particular promise due to its moisture resistance and compatibility with lighter lanthanide dopants, addressing a significant limitation of many low-phonon energy materials that typically suffer from hygroscopic instability.

The crystalline structure of potassium-lead-halide hosts creates an optimal environment for dopant incorporation, with the Pb²⁺ sites providing favorable coordination for trivalent lanthanide ions through charge compensation mechanisms. Structural analysis reveals that these hosts maintain high crystallinity even at nanoscale dimensions, preserving the optical properties essential for efficient photon avalanche. The ability to synthesize these materials as monodisperse nanoparticles with controlled sizes down to 30 nanometers enables precise tuning of their photonic properties while facilitating integration into optical devices and biological systems [15].

Neodymium Dopant Properties and Incorporation

Neodymium ions (Nd³⁺) serve as the active centers responsible for the photon avalanche effect in potassium-lead-halide nanocrystals. The Nd³⁺ electronic structure features multiple energy levels that enable the complex series of transitions required for avalanche behavior, including the ⁴I₉/₂ ground state, ⁴F₅/₂ excited state, and ⁴F₃/₂ metastable state that serves as the bottleneck level in the avalanche process. The relative energy matching between these states and the host band structure allows for efficient excited-state absorption and cross-relaxation processes.

Successful incorporation of Nd³⁺ into the KPb₂X₅ host requires careful control of dopant concentration, typically ranging from 1-5%, to balance the competing requirements of efficient energy transfer while minimizing concentration quenching effects. At optimal doping levels, the average distance between Nd³⁺ ions facilitates rapid cross-relaxation (⁴F₃/₂ → ⁴F₅/₂ and ⁴I₉/₂ → ⁴I₁₅/₂) while maintaining sufficient isolation to prevent cooperative deactivation. The substitution of Pb²⁺ with Nd³⁺ introduces charge imbalance that necessitates compensation through halide vacancies or interstitial ions, subtly modifying the local crystal field and influencing the optical properties of the dopant ions.

Table: Key Properties of Potassium-Lead-Halide Host and Neodymium Dopant

| Parameter | KPb₂Cl₅ | KPb₂Br₅ | Nd³⁺ Dopant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phonon Energy | 128-140 cm⁻¹ | 130-150 cm⁻¹ | N/A |

| Crystal Structure | Monoclinic | Monoclinic | N/A |

| Band Gap | ~4.0 eV | ~3.5 eV | N/A |

| Moisture Stability | High | Moderate | N/A |

| Primary Absorption | N/A | N/A | 808 nm (⁴I₉/₂ → ⁴F₅/₂) |

| Emission Wavelengths | N/A | N/A | 1060 nm (⁴F₃/₂ → ⁴I₁₁/₂) |

| Optimal Concentration | N/A | N/A | 1-5% |

Photon Avalanche Mechanism in Nd³⁺-Doped Systems

The photon avalanche process in Nd³⁺-doped potassium-lead-halide nanocrystals operates through a sophisticated mechanism that generates extreme optical nonlinearity. This process can be visualized through the following energy transfer pathway:

The avalanche mechanism initiates with weak ground-state absorption where incident photons at specific wavelengths (typically 1064 nm) are non-resonantly absorbed, promoting a small number of Nd³⁺ ions from the ⁴I₉/₂ ground state to higher energy levels. These excited ions rapidly relax to the ⁴F₃/₂ metastable state, which serves as the critical bottleneck level in the process. The population of this metastable state enables resonant excited-state absorption, where ions in the ⁴F₃/₂ state efficiently absorb additional pump photons, promoting them to higher-lying energy states (⁴D₃/₂ or ⁴D₅/₂).

The critical amplification step occurs through cross-relaxation energy transfer, where highly excited ions transfer part of their energy to neighboring ground-state ions, resulting in two ions in the intermediate metastable state for each original excited ion. This creates a positive feedback loop where the intermediate state population grows exponentially, leading to the characteristic avalanche effect. The process culminates in intense upconverted emission at various wavelengths, including visible regions (480-700 nm), despite excitation in the near-infrared range.

The extreme nonlinearity of this process in Nd³⁺-doped potassium-lead-halide nanocrystals arises from the synergistic combination of the host's low phonon energies, which minimize non-radiative losses, and the specific energy level structure of Nd³⁺, which enables efficient cross-relaxation pathways. This combination results in nonlinearity coefficients exceeding 70, meaning that doubling the pump power increases emission intensity by more than 2⁷⁰-fold—the highest nonlinearities observed in any material system [15].

Synthesis and Experimental Protocols

Nanocrystal Synthesis Methodology

The synthesis of high-quality Nd³⁺-doped potassium-lead-halide nanocrystals follows a carefully optimized colloidal approach that enables precise control over size, composition, and optical properties. The following workflow illustrates the key stages in the synthesis process:

The synthesis begins with preparation of precursor solutions containing lead halide (PbX₂), potassium halide (KX), and neodymium oleate (Nd(oleate)₃) in appropriate molar ratios to achieve the target doping concentration. These precursors are dissolved in oleylamine and octadecene, which serve as both solvent and surfactant. The solution is heated to 160-180°C under inert atmosphere to ensure complete dissolution and prevent oxidation.

The hot-injection technique is employed to initiate rapid nucleation, where a small volume of precursor solution is swiftly injected into the hot surfactant mixture. This creates a temporary supersaturation that promotes homogeneous nucleation. The temperature is immediately reduced to 120-140°C for the crystal growth phase, which continues for 30-60 minutes with constant stirring to allow controlled Ostwald ripening and uniform doping incorporation.

The reaction is terminated by rapid quenching in an ice bath, ceasing further growth and stabilizing the nanocrystal surface. Purification steps involve repeated centrifugation and redispersion in non-polar solvents (typically hexane or toluene) with addition of antisolvents (ethanol or acetone) to remove unreacted precursors and surfactant byproducts. The final nanocrystals can be dispersed in various organic solvents or functionalized with ligand exchange for specific application requirements.

Key Experimental Protocols for Avalanche Characterization

Characterization of photon avalanche behavior requires specialized experimental setups to accurately measure the extreme nonlinear response and temporal dynamics. The following protocols are essential for comprehensive analysis:

Nonlinear Power Dependence Measurement: Specimens are excited using a continuous-wave infrared laser (1064 nm) with precisely controlled power levels. Emission is collected through appropriate spectral filters (700-900 nm bandpass) and detected using a photomultiplier tube or superconducting single-photon detector. Power is systematically varied across 3-5 orders of magnitude using calibrated neutral density filters, with particular attention to the threshold region where nonlinear response initiates. Emission intensity is plotted against pump power on logarithmic scales to determine the nonlinearity coefficient from the slope of the linear region.

Time-Resolved Avalanche Dynamics: Pulsed excitation (1-100 μs pulses) is employed to investigate the characteristic slow rise times of avalanche emission. Time-correlated single-photon counting techniques with nanosecond resolution capture the emission buildup, which typically extends from microseconds to milliseconds depending on proximity to the avalanche threshold. Analysis of rise time versus pump power provides insight into the feedback dynamics and energy transfer efficiency.

Single-Particle Spectroscopy: Dilute nanocrystal dispersions are spin-coated onto clean substrates for single-particle measurements using a confocal microscope with diffraction-limited spatial resolution. This technique confirms uniform avalanche behavior across the population and identifies potential heterogeneities in nonlinear response. Photon correlation measurements can further elucidate the underlying energy transfer mechanisms.

Table: Standard Characterization Parameters for Avalanche Analysis

| Measurement | Excitation Conditions | Detection Parameters | Key Output Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power Dependence | CW, 1064 nm, 10⁴-10⁹ W/m² | 700-900 nm emission, log-scale plot | Nonlinearity coefficient, Threshold power |

| Time Dynamics | Pulsed, 1-100 μs, 1064 nm | Time-correlated single photon counting | Rise time, Decay lifetime, Bottleneck population |

| Spectral Analysis | CW, 1064 nm, above threshold | Spectrograph with NIR-visible CCD | Emission wavelengths, Branching ratios |

| Single Particle | CW/pulsed, focused to diffraction limit | Confocal detection with APD | Intensity trajectories, Threshold distribution |

Optical Properties and Performance Metrics

Nd³⁺-doped potassium-lead-halide nanocrystals exhibit extraordinary optical properties that directly translate to their exceptional performance in photon avalanche applications. The quantitative metrics for these materials represent the state-of-the-art in nonlinear nanophotonics.

Nonlinear Optical Characteristics

The defining feature of these nanomaterials is their extreme optical nonlinearity, characterized by a sharp excitation threshold beyond which emission intensity increases superlinearly with pump power. Recent measurements demonstrate nonlinearity coefficients of 70-100, meaning that doubling the excitation power produces an emission increase of 2⁷⁰ to 2¹⁰⁰ fold [15]. This represents the highest nonlinearity observed in any material system and enables unique applications in optical computing where strong nonlinear response is essential for switching and memory functions.

The avalanche threshold power typically falls in the range of 10⁶-10⁸ W/m² for ensemble measurements, with variations depending on nanocrystal size, doping concentration, and surface quality. Single-particle studies reveal additional heterogeneity in threshold values, reflecting subtle differences in local environment and energy transfer efficiency between individual nanocrystals. The threshold power demonstrates temperature dependence, decreasing at elevated temperatures due to enhanced phonon-assisted processes that facilitate the initial ground-state absorption step.

Temporal Dynamics and Spectral Features

The temporal dynamics of photon avalanche in these systems exhibit characteristic "slow rise times" that prolong from microseconds to milliseconds near the threshold region—a signature property of avalanche processes known as "critical slowing down." This extended rise time reflects the cumulative nature of the population buildup in the intermediate metastable state through multiple cycles of excited-state absorption and cross-relaxation. Above threshold, rise times shorten dramatically but remain considerably longer than the intrinsic excited-state lifetime of the emitting level.

Spectral analysis reveals efficient upconversion emission across multiple wavelength regions despite single-wavelength infrared excitation. Prominent emission bands include:

- ~480-550 nm (blue-green) corresponding to ⁴D₃/₂ → ⁴I₉/₂ and ⁴D₃/₂ → ⁴I₁₁/₂ transitions

- ~600-700 nm (red) from ⁴D₃/₂ → ⁴I₁₃/₂ transitions

- ~800-900 nm (NIR) from ⁴F₃/₂ → ⁴I₉/₂ transitions

The relative intensity of these bands varies with pump power and doping concentration, providing additional handles for tuning the optical response for specific applications.

Table: Performance Comparison of Nd³⁺-Doped Avalanche Nanocrystals

| Parameter | KPb₂Cl₅:Nd³⁺ | KPb₂Br₅:Nd³⁺ | Conventional NaYF₄:Tm³⁺ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonlinearity Coefficient | 70-100 | 50-80 | 20-30 |

| Threshold Power (W/m²) | 10⁶-10⁷ | 10⁷-10⁸ | 10⁸-10⁹ |

| Rise Time (near threshold) | 10-100 μs | 5-50 μs | 1-10 ms |

| Phonon Energy (cm⁻¹) | 128-140 | 130-150 | ~350 |

| Emission Range | 480-900 nm | 480-900 nm | 450-800 nm |

| Quantum Efficiency | 0.5-5% | 0.1-2% | 0.01-0.1% |

Application in Optical Computing

The extraordinary properties of Nd³⁺-doped potassium-lead-halide ANPs directly address key challenges in optical computing, particularly in developing nanoscale optical memory and switching elements that operate at low power thresholds while maintaining compatibility with existing microelectronic fabrication scales.

Optical Memory and Bistability

The most significant computing application of these ANPs leverages their intrinsic optical bistability—the ability to maintain two distinct emission states under identical excitation conditions based on excitation history [15]. This bistability emerges directly from the extreme nonlinearity of the photon avalanche process combined with specific structural properties that dampen vibrational losses. When excited above threshold, these nanoparticles transition to a brightly emitting state that persists even when pump power is reduced below the original threshold power, creating a hysteresis loop in the input-output power relationship.

This hysteresis enables volatile memory functionality analogous to electronic random-access memory (RAM), where the "on" state represents binary 1 and the "off" state binary 0. The large difference between "on" and "off" threshold powers (typically a factor of 3-5×) creates a robust operating window where the system state depends solely on its excitation history rather than instantaneous input. The 30-nanometer dimensions of these functional memory elements approach the scale of current electronic transistors, potentially enabling dense integration of optical computing elements [15].

Optical Switching and Transistor Applications

The extreme nonlinear response of these ANPs enables their use as optical switches where small changes in input power produce dramatic changes in output emission. The effectively infinite slope of the power dependence curve at threshold means that minimal modulation of pump intensity can switch emission between completely "off" and fully "on" states, providing the essential gain required for transistor operation. When integrated into waveguide structures or optical cavities, these nanoparticles can control signal propagation through all-optical means without conversion to electronic signals.

The development of ANP-based optical transistors is particularly promising for specialized computing architectures, including neuromorphic systems that mimic neural processing. The slow rise times and history-dependent responses of avalanche nanoparticles resemble the temporal integration and firing characteristics of biological neurons, potentially enabling more efficient implementation of neural networks in hardware rather than software simulation. Recent demonstrations have shown that ANP systems can perform basic logical operations (AND, OR, NOT) and signal processing functions entirely through light-matter interactions [2] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Materials

Successful research on Nd³⁺-doped potassium-lead-halide photon avalanching nanoparticles requires specific materials and instrumentation. The following table details essential research reagent solutions and their functions:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Synthesis and Characterization

| Category | Specific Materials | Function/Purpose | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursors | Lead(II) chloride (PbCl₂), Lead(II) bromide (PbBr₂), Potassium chloride (KCl), Potassium bromide (KBr) | Host matrix formation | Anhydrous, 99.99% purity recommended |

| Dopant Sources | Neodymium(III) acetate, Neodymium(III) oleate, Neodymium(III) acetylacetonate | Nd³⁺ ion incorporation | Oleate form provides best solubility |

| Solvents | Oleylamine, 1-Octadecene, Toluene, Hexane | Reaction medium, dispersion | Anhydrous, oxygen-free conditions |

| Surfactants | Oleic acid, Trioctylphosphine, Trioctylphosphine oxide | Surface stabilization, size control | Impact nanocrystal shape and dispersity |

| Excitation Sources | 1064 nm CW laser (Nd:YVO₄), Tunable NIR laser (760-1100 nm) | Avalanche excitation | Temperature stabilization critical |

| Detection Systems | Spectrograph with NIR-optimized CCD, Photomultiplier tubes, Single-photon avalanche diodes | Emission collection and analysis | NIR sensitivity essential |

| Optical Filters | 1000 nm short-pass, 700-900 nm bandpass | Spectral selection, stray light rejection | High optical density at laser wavelength |

Nd³⁺-doped potassium-lead-halide nanocrystals represent a groundbreaking material system that combines unprecedented optical nonlinearity with nanoscale dimensions ideally suited for optical computing applications. Their exceptional properties stem from the synergistic combination of an ultra-low phonon energy host matrix and optimally matched neodymium dopant ions that enable efficient photon avalanche through engineered energy transfer pathways.

Future research directions should focus on enhancing the environmental stability of these materials for practical device integration, exploring heterostructure designs that further reduce avalanche thresholds, and developing precise doping control techniques to optimize energy transfer efficiency. Additionally, integration with photonic cavities and waveguides could enhance nonlinear performance while reducing operational power requirements. As synthesis methods advance and fundamental understanding of the avalanche mechanism deepens, these extraordinary nanomaterials are poised to enable transformative advances in optical computing, potentially revolutionizing information processing through all-optical computing platforms that leverage their unique history-dependent nonlinear responses.

The synergistic interplay between excited-state absorption (ESA) and cross-relaxation (CR) constitutes a powerful positive feedback loop that enables some of the most nonlinear optical phenomena known to science. This mechanism is most dramatically manifested in photon avalanching (PA) nanoparticles, where it produces unprecedented optical nonlinearities critical for advancing optical computing research. In lanthanide-based nanomaterials, this feedback loop creates a self-amplifying cycle where a small increase in pump power triggers a disproportionate, often exponential, rise in high-energy emission [2] [3].

The unique power of this mechanism lies in its ability to generate ultrahigh-order optical nonlinearity at the nanoscale under continuous-wave, low-power excitation conditions. Unlike conventional multiphoton processes that require intense pulsed lasers, the ESA-CR feedback loop operates through real energy states that accumulate population over time, creating a nonlinear optical response that can reach tens to hundreds of orders of magnitude [2] [7]. This extraordinary capability is redefining possibilities in nanophotonics, particularly for optical computing applications where nonlinear optical elements are essential components.

Table 1: Fundamental Processes in the ESA-CR Feedback Loop

| Process | Mechanism | Role in Feedback Loop | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ground-State Absorption (GSA) | Single photon absorption from ground state | Initiator cycle | Typically very weak; non-resonant with excitation |

| Excited-State Absorption (ESA) | Sequential absorption of second photon from intermediate excited state | Amplification driver | Resonant with excitation; requires long-lived intermediate states |

| Cross-Relaxation (CR) | Energy transfer between neighboring ions producing two intermediately-excited ions | Population multiplication | Enables positive feedback; concentration-dependent |

| Energy Transfer Upconversion (ETU) | Energy transfer between two excited ions | Alternative UC pathway | Involves two different ions; no looping capability |

The Photon Avalanche Mechanism: A Detailed Look

Component Processes

The photon avalanche mechanism emerges from the precise coordination of three fundamental physical processes, each playing a distinct role in establishing the positive feedback loop:

Weak Ground-State Absorption (GSA): The process initiates when a lanthanide ion weakly absorbs a photon through non-resonant GSA, populating an intermediate metastable state (E1). This transition is intentionally inefficient, with the excitation energy not perfectly matching the ground-state transition energy [2] [3].

Resonant Excited-State Absorption (ESA): From the intermediate state E1, the ion resonantly absorbs a second photon of the same energy, promoting it to a higher excited state (E2). This ESA process possesses a much stronger cross-section than GSA, typically by a factor exceeding 10,000, creating the asymmetry necessary for avalanching behavior [2].

Ion-Pair Cross-Relaxation (CR): The critically enabling process involves energy transfer between an ion in the high-energy E2 state and a neighboring ground-state ion. Through a resonant dipole-dipole interaction, both ions end up in the intermediate E1 state. This single excitation event thus produces two ions prepared for further ESA, effectively doubling the intermediate state population with each cycle [16] [3].

The Feedback Loop in Action

The positive feedback emerges from the iterative repetition of these processes. Once initiated, the cycle follows this sequence: (1) ESA promotes an E1 ion to E2; (2) CR transfers energy from E2 to a ground-state neighbor, producing two E1 ions; (3) these two E1 ions undergo ESA to become two E2 ions; (4) each E2 ion undergoes CR with ground-state neighbors, producing four E1 ions. This exponential growth continues until limited by the available ion population or excitation power [3].

The feedback loop manifests three distinctive experimental hallmarks: (1) a clear excitation threshold below which emission is minimal and above which it surges dramatically; (2) an S-shaped power dependence where luminescence intensity follows a highly nonlinear relationship with pump power; and (3) prolonged rise times extending from tens to hundreds of milliseconds near threshold, reflecting the slow buildup of the intermediate state population [2].

Quantitative Characterization of Avalanching Systems

Key Performance Metrics

The extreme nonlinearity of PA nanoparticles is quantitatively characterized through several key parameters that determine their suitability for optical computing applications:

Nonlinearity Order (n): PA nanoparticles exhibit unprecedented nonlinearity orders, with recent reports reaching n > 30 under continuous-wave excitation. This represents a 30th-power dependence of emission intensity on excitation power, far exceeding conventional multiphoton processes typically limited to n = 2-5 [7].

Avalanche Threshold (Ith): The specific pump power density at which the positive feedback becomes self-sustaining. Optimal PA nanoparticles demonstrate thresholds below 1 MW/cm² under continuous-wave excitation, making them compatible with common diode lasers [3].

Rise Time (τrise): The characteristic time for emission to reach steady-state after excitation initiation. Near threshold, this slowing-down effect can extend to hundreds of milliseconds due to the critical dynamics of the feedback loop [2].

ESA/GSA Cross-Section Ratio: The asymmetry between excited-state and ground-state absorption probabilities, with effective ratios exceeding 10,000 in optimized PA systems [2].

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters of Representative PA Nanoparticles

| Material System | Nonlinearity Order (n) | Avalanche Threshold | Rise Time | Emission Wavelength | Excitation Wavelength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaYF₄:Tm³⁺ | 10-15 | ~0.1-1 MW/cm² | 10-100 ms | ~800 nm | 1064 nm or 1450 nm |

| KPb₂Cl₅:Nd³⁺ | >20 | < 1 MW/cm² | < 10 ms | ~860 nm | 1064 nm |

| NaLuF₄:Tm³⁺ | >30 | ~0.5 MW/cm² | ~9 ms | ~800 nm | 1064 nm |

| LaF₃:Pr³⁺ (bulk) | 5-10 | ~1 MW/cm² | 10-50 ms | Visible (green/red) | ~850 nm |

Host Matrix and Dopant Engineering

The host lattice fundamentally governs PA efficiency through multiple parameters:

Phonon Energy: Low-phonon-energy hosts (< 350 cm⁻¹) like NaYF₄, NaGdF₄, and KMgF₃ minimize non-radiative decay, preserving intermediate state populations essential for the feedback loop [2].

Lattice Constants: Smaller lattice parameters, as in NaLuF₄ versus NaYF₄, create stronger crystal fields around lanthanide dopants, enhancing transition probabilities and increasing nonlinearity [2].

Cation Sites: The random distribution of Sr²⁺ and La³⁺ in SrLaGaO₄ creates structural disorder that broadens optical transitions, facilitating spectral overlap for energy transfer processes [17].

Dopant selection follows specific requirements: Tm³⁺, Nd³⁺, Pr³⁺, Ho³⁺, and Er³⁺ possess the ladder-like energy level structure necessary for PA, with Tm³⁺ being particularly efficient due to its matched energy gaps enabling resonant CR between the ³H₄ and ³F₄ levels [16] [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Material Synthesis and Optimization

The synthesis of high-performance PA nanoparticles requires precise control over dopant distribution and surface chemistry:

Hot-Injection Method: For NaYF₄-based PA nanoparticles, the synthesis begins with heating yttrium, ytterbium, and thulium precursors in oleic acid and octadecene to 150-160°C under argon atmosphere. A solution of sodium and fluoride precursors in methanol is rapidly injected, and the reaction proceeds at 290-310°C for 30-60 minutes. Critical parameters include exact stoichiometric control with Tm³⁺ concentrations typically between 0.5-8% and Yb³⁺ concentrations of 10-25% [3].

Core-Shell Architecture: To suppress surface quenching sites that disrupt the PA cycle, an inert shell of undoped NaYF₄ is grown epitaxially around the doped core. The shell thickness is optimized to balance surface passivation (thicker shells) against maintaining high energy transfer rates (thinner shells), with typical optimal thicknesses of 2-5 nm [2] [3].

Post-Synthetic Treatment: Ligand exchange with polyethylene glycol or other hydrophilic molecules enables water dispersibility for biological applications, while thermal annealing improves crystallinity and reduces defect densities [3].

Spectroscopic Characterization

Comprehensive optical characterization is essential to confirm authentic PA behavior and distinguish it from other upconversion mechanisms:

Power Dependence Measurements: Emission intensity is measured across a wide range of excitation powers (typically 10⁻³ to 10² MW/cm²). Data is plotted on a log-log scale, with the slope in the high-power regime giving the nonlinearity order. True PA exhibits a characteristic S-shaped curve with a clear threshold [2] [3].

Time-Resolved Luminescence: Rise and decay dynamics are measured using a modulated continuous-wave laser and time-correlated single photon counting. Near the avalanche threshold, the rise time exhibits dramatic prolongation due to critical slowing down [2].

Lifetime Measurements: The lifetime of the intermediate metastable state (³H₄ in Tm³⁺, ¹G₄ in Pr³⁺) is measured under weak, non-avalanching conditions to confirm sufficient storage capacity for the feedback loop. Optimal systems show lifetimes exceeding 100 μs [17] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for PA Nanoparticle Research

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Notes | Optimal Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaYF₄ host matrix | Primary crystal lattice | Low phonon energy (~350 cm⁻¹) | Hexagonal phase preferred over cubic |

| Tm³⁺ dopant ions | Avalanche activator | Enables ESA/CR feedback loop | 0.5-8% concentration range |

| Yb³⁺ sensitizer ions | Absorption enhancement | Increases GSA efficiency | 10-25% concentration |

| Oleic acid/ODE solvent | Synthesis medium | High-temperature stable | Anoxic conditions required |

| NH₄F/NaOH precursors | Fluoride source | Controlled nucleation | Rapid injection critical |

| Inert shell materials | Surface passivation | Reduces non-radiative decay | 2-5 nm thickness optimal |

| PEG ligands | Biocompatibilization | Aqueous dispersion | Post-synthetic exchange |

Applications in Optical Computing Research

The extreme nonlinearity and intrinsic optical bistability of PA nanoparticles directly address several key challenges in optical computing:

Nanoscale Optical Memory and Switching

PA nanoparticles exhibit intrinsic optical bistability (IOB), where the same input power can sustain either high-emission ("on") or low-emission ("off") states depending on the system's history. This hysteresis effect enables memory functionality at the nanoscale. Recent demonstrations show that PA nanoparticles can maintain bistable states with power separations of just 1-10% between on and off thresholds, making them suitable for ultra-compact optical memory elements [7].

The operational principle leverages the nonlinear power dependence: below threshold, the system remains in the off state; once switched on by exceeding the threshold, it can maintain the on state even when power is reduced below the original switching threshold. This creates the necessary hysteresis loop for binary memory storage. The first practical demonstration of IOB in nanoscale materials used 30-nm potassium-lead-halide nanoparticles doped with neodymium, exhibiting near-instantaneous switching times compatible with computing applications [7].

Optical Transistors and Logic Gates

The giant nonlinearity of PA nanoparticles enables implementation of optical transistors where a small gate signal controls a much stronger output. Research has shown that PA-based optical transistors can achieve gain factors exceeding 10,000, significantly outperforming conventional nonlinear optical materials [7]. These nanoparticles can be configured into fundamental logic gates (AND, OR, NOT) through appropriate optical interconnections, providing the building blocks for more complex optical computing circuits.

The unique property of "critical slowing down" near the avalanche threshold—where the system response time dramatically increases—can be harnessed for temporal integration of optical signals, mimicking the functionality of biological synapses. This capability is particularly valuable for neuromorphic computing architectures that process information in ways inspired by the human brain [2].

Implementation Considerations for Optical Computing

Integrating PA nanoparticles into practical optical computing systems requires addressing several implementation challenges:

Environmental Stability: Protection from moisture and oxygen through proper encapsulation in polymer matrices or inorganic coatings [3].

Heat Management: Despite operating under relatively low power continuous-wave excitation, the high localized energy densities in PA nanoparticles can generate significant heat, requiring efficient thermal management strategies [7].

Addressing and Interconnection: Developing methods for individually addressing densely-packed PA nanoparticle arrays while minimizing cross-talk between adjacent elements [2] [7].

Fabrication Scalability: Transitioning from laboratory-scale synthesis to mass production while maintaining precise control over nanoparticle size, composition, and optical properties [3].

Current research focuses on integrating PA nanoparticles with photonic waveguides, plasmonic structures, and microcavities to enhance light-matter interaction and reduce operational thresholds further. These hybrid approaches promise to deliver the necessary performance characteristics for practical optical computing implementations in the near future [2] [3].

The positive feedback loop between excited-state absorption and cross-relaxation in photon avalanching nanoparticles represents a uniquely powerful mechanism for generating extreme optical nonlinearities at the nanoscale. As research continues to refine our understanding and control of these materials, their implementation in optical computing architectures promises to overcome fundamental limitations in miniaturization, speed, and energy efficiency. The quantitative framework and experimental methodologies outlined in this technical guide provide researchers with the foundational knowledge necessary to advance this rapidly evolving field toward practical optical computing applications.

Intrinsic optical bistability (IOB) represents a fundamental property in photonic materials wherein a system can maintain two distinct optical states—such as glowing brightly or remaining dark—under identical steady-state excitation conditions. This binary behavior enables materials to function as optical memory or switching components, forming the foundational building blocks for optical computing systems that use light instead of electricity for processing information. For decades, researchers have pursued the goal of creating computers that leverage light rather than electricity, and materials exhibiting IOB have long been identified as critical components for such technology. The ability to switch between optical states without changing the material itself provides a pathway for developing volatile random-access memory (RAM) and transistors for next-generation computers [15].

Historically, the realization of practical IOB has faced significant challenges. Prior research had almost exclusively demonstrated optical bistability in bulk materials that were too large for integration into microchips and presented substantial difficulties for mass production. These bulk material systems, while proving the scientific concept, were incompatible with the size constraints of modern microelectronics. In the few reported instances where nanoscale IOB was observed, the underlying processes were not well understood and were frequently attributed to nanoparticle heating—an inefficient and difficult-to-control mechanism that hampered practical application [15]. This size limitation created a significant barrier to progress in optical computing, as practical implementations require components that can be fabricated at scales comparable to contemporary electronic transistors, typically measured in nanometers.

The core challenge thus became clear: how to achieve genuine, controllable IOB at the nanoscale in a manufacturable format. This whitepaper documents how recent breakthroughs in photon avalanching nanoparticles have successfully overcome these historical limitations, enabling the first practical demonstration of IOB in nanoscale materials and paving the way for their integration into optical computing architectures [8].

The Photon Avalanche Mechanism: Foundation for Nanoscale IOB

Photon avalanching (PA) is an unconventional upconversion process driven by a powerful positive feedback loop that couples nonresonant ground-state absorption (GSA), resonant excited-state absorption (ESA), and highly efficient cross-relaxation (CR) between neighboring ions. This synergistic interaction produces a threshold-triggered ultrahigh optical nonlinearity accompanied by uniquely prolonged rise-time dynamics [2]. The phenomenon can deliver tens to hundreds of nonlinear orders at the nanoscale, redefining opportunities not only in optical computing but also in imaging and sensing applications [2].

The operational hallmarks of photon avalanching include three distinctive characteristics that differentiate it from other nonlinear optical processes. First, it requires a strong ESA cross-section coupled with a much weaker GSA cross-section, typically exhibiting a rate ratio exceeding 10,000:1. Second, it demonstrates a clear excitation threshold power marking the abrupt onset of intense nonlinear emission. Third, it exhibits prolonged luminescence rise-times extending from tens to hundreds of milliseconds, particularly detectable near the excitation threshold [2]. These characteristics collectively distinguish PA from other multiphoton processes and provide a shared technical framework that enables cross-laboratory comparability and rigorous peer evaluation.

In conventional luminescent materials, strong cross-relaxation induced by high dopant concentrations is typically viewed as detrimental, as it depopulates emissive levels and causes concentration quenching. However, in specially engineered lanthanide-doped nanoparticles, the construction of PA leverages relatively high dopant densities to ensure sufficiently short interionic distances for efficient energy transfer [2]. Contrary to conventional wisdom, in these optimized systems, strong cross-relaxation can actually suppress surface quenching effects and facilitate population accumulation in intermediate metastable states rather than acting merely as a loss channel. This counterintuitive behavior is key to achieving the extreme nonlinearities required for practical IOB at the nanoscale.

Table: Key Characteristics of Photon Avalanching Nanoparticles

| Characteristic | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Nonlinearity | >200th-order nonlinearities observed | Highest nonlinearities ever recorded in any material [15] |

| Threshold Behavior | Sharp transition between "off" and "on" states at specific excitation power | Enables binary switching behavior essential for computing [15] |

| Hysteresis | Different power thresholds for switching "on" vs. "off" | Creates memory capability based on excitation history [15] |

| Rise Time | Prolonged luminescence buildup (milliseconds to seconds) | Distinctive kinetic signature useful for temporal control [2] |

| Size Regime | ~30 nanometer particles | Compatible with current microelectronic fabrication [8] |

The mechanistic foundation of IOB in these advanced nanoparticles arises not from thermal effects as previously assumed, but from the extreme nonlinearity intrinsic to photon avalanching combined with unique nanostructures that effectively dampen vibrational energy [15]. This all-optical mechanism represents a paradigm shift in understanding and designing nanoscale optically bistable systems.

Historical Trajectory: From Bulk Crystals to Engineered Nanocrystals

The journey from bulk materials to practical nanoscale IOB has spanned nearly five decades, marked by periods of dormancy followed by rapid resurgence. The photon avalanche phenomenon was first observed in 1979 when researchers documented an exponential surge of fluorescence from Pr³⁺-doped LaCl₃ and LaBr₃ crystals under continuous-wave green excitation resonant with the ESA transition [2]. Subsequent investigations throughout the 1980s and 1990s gradually deepened the mechanistic understanding of this process, yet progress remained largely constrained to low-temperature bulk crystal systems. These early materials were clouded by misconceptions, and the PA phenomenon was often dismissed as an unstable optical amplification effect without a clear path to practical control or application.

During this period, reports of upconversion behaviors showing apparent emission orders beyond four—outside the explanatory reach of conventional excited-state absorption/energy transfer upconversion (ESA/ETU) frameworks—were frequently and prematurely attributed to PA without definitive evidence. This conceptual ambiguity, combined with the absence of compelling application scenarios, marginalized PA research within the broader landscape of lanthanide upconversion studies [2]. The field languished not because the phenomenon was unimportant, but because the available material systems failed to provide a pathway to practical implementation.

Two critical developments catalyzed the recent resurgence of PA at the nanoscale. First, the advent of highly sensitive photon-detection technologies enabled researchers to observe and characterize the subtle dynamics of PA in small particles with unprecedented precision. Second, breakthroughs in nanomaterial synthesis and structural design provided the necessary control over composition, architecture, and surface properties to engineer nanoparticles with optimized PA performance [2]. These parallel advancements transformed PA from a laboratory curiosity into a deliberately designable and tunable engine of ultrahigh-order nonlinearity.

The pivotal moment in this transition came with the development of 30-nanometer nanoparticles fabricated from a potassium-lead-halide material doped with neodymium, a rare-earth element commonly used in lasers [15]. When excited with light from an infrared laser, these nanoparticles exhibited a dramatically enhanced photon avalanching effect—over three times more nonlinear than previous avalanching nanoparticles—representing the highest nonlinearities ever observed in any material [15]. Crucially, researchers discovered that these nanoparticles not only exhibited photon avalanching properties when excited above a given laser power threshold but also continued to emit brightly even when the laser power was reduced below that threshold, only turning off completely at very low laser powers. This hysteresis effect manifested the long-sought intrinsic optical bistability at a truly practical nanoscale [15] [8].

Breakthrough Material Systems: Composition, Structure, and Properties

The successful realization of nanoscale IOB hinges on precisely engineered material systems that optimize both composition and architecture for photon avalanching performance. The foundational breakthrough system consists of 30-nanometer nanoparticles based on a potassium-lead-chloride host lattice doped with neodymium ions [8]. This specific composition was not arbitrarily selected but emerged from systematic investigation of host-dopant combinations that could simultaneously support efficient energy transfer, minimize non-radiative losses, and provide the crystal field properties necessary for avalanche behavior.