Organic vs. Inorganic Nanoparticles: A Comprehensive Analysis of Toxicity Profiles for Safer Drug Development

This article provides a systematic comparison of the toxicity profiles of organic and inorganic nanoparticles, crucial for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the safety landscape of nanomedicine.

Organic vs. Inorganic Nanoparticles: A Comprehensive Analysis of Toxicity Profiles for Safer Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of the toxicity profiles of organic and inorganic nanoparticles, crucial for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the safety landscape of nanomedicine. It explores the fundamental physicochemical properties dictating nanotoxicity, details advanced in vitro and in vivo assessment methodologies, and outlines strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing nanoparticle safety. A direct comparative analysis highlights the distinct advantages and challenges associated with each nanoparticle class, synthesizing key takeaways to guide the rational design of safer, more effective nanotherapeutics and inform future regulatory frameworks.

Unraveling the Core: Physicochemical Properties and Mechanisms Driving Nanoparticle Toxicity

In the evolving landscape of nanotechnology, nanoparticles (NPs) are defined as particles with at least one dimension ranging from 1 to 100 nanometers, where unique physicochemical properties emerge that are distinct from their bulk counterparts [1] [2]. These materials have become foundational to modern biomedical research, enabling revolutionary advances in drug delivery, diagnostic imaging, and therapeutic interventions. The international scientific community, including organizations like the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the European Commission, recognizes nanomaterials as materials with external dimensions or internal structures at the nanoscale, typically within the 1-100 nm range, though definitions may vary slightly between regulatory bodies [1]. For biomedical applications specifically, nanoparticles used in drug delivery often fall within a slightly broader range of 10-200 nm to optimize biodistribution and targeting efficiency [3].

The classification of nanoparticles into organic and inorganic categories represents a fundamental distinction based on their core composition and structural organization. This classification directly influences their biological behavior, therapeutic potential, and toxicity profiles—factors of critical importance to researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working to translate nanomedicine from laboratory research to clinical applications. Organic nanoparticles are primarily composed of carbon-based frameworks and include structures such as liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, dendrimers, and micelles. In contrast, inorganic nanoparticles encompass non-carbon-based materials including metals, metal oxides, semiconductors, and silica-based nanostructures [1] [3] [4]. The strategic selection between organic and inorganic nanoparticles depends heavily on the specific biomedical application, desired pharmacokinetics, and acceptable safety profile, necessitating a thorough understanding of their comparative characteristics.

Composition and Structural Organization

The fundamental distinction between organic and inorganic nanoparticles originates from their atomic composition and structural architecture, which directly dictate their physical properties and biological interactions.

Organic Nanoparticles: Carbon-Based Architectures

Organic nanoparticles are predominantly composed of carbon-based molecules arranged in specific configurations to form nanostructures. The most prevalent categories include:

Liposomes: Spherical vesicles consisting of one or more phospholipid bilayers surrounding an aqueous core, typically ranging from 50-100 nm in diameter. Their amphiphilic nature allows for encapsulation of both hydrophilic (in the aqueous interior) and hydrophobic (within the lipid bilayer) therapeutic agents [4]. Common phospholipids include phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and phosphatidylserine, often stabilized with cholesterol to enhance structural integrity [4].

Polymeric Nanoparticles: These include nanospheres (matrix systems where drugs are dispersed throughout) and nanocapsules (reservoir systems where drugs are confined to an inner cavity surrounded by a polymeric membrane) [1]. They are typically synthesized from biodegradable polymers such as polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA), poly(lactic acid) (PLA), or poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL).

Dendrimers: Highly branched, monodisperse synthetic polymers with a tree-like architecture featuring a central core, interior branches, and terminal functional groups. This precise structure enables controlled drug conjugation and release kinetics [5].

Micelles: Self-assembled structures formed from amphiphilic block copolymers in aqueous solutions, typically 10-100 nm in diameter, with a hydrophobic core and hydrophilic shell suitable for delivering poorly water-soluble drugs [1].

Inorganic Nanoparticles: Non-Carbon Frameworks

Inorganic nanoparticles encompass a diverse range of non-carbon-based materials with unique electronic, magnetic, and optical properties:

Metal Nanoparticles: Include noble metals such as gold (Au), silver (Ag), and platinum (Pt) nanoparticles. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are particularly notable for their tunable surface plasmon resonance, biocompatibility, and ease of surface functionalization [1] [4]. They can be synthesized in various shapes including spheres, rods, cubes, and triangles, each with distinct optical properties [4].

Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: Comprise materials such as iron oxide (Fe₃O₄ or γ-Fe₂O₃), zinc oxide (ZnO), titanium dioxide (TiO₂), and cerium oxide (CeO₂). Iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) exhibit superparamagnetic properties when smaller than 20 nm, making them valuable for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic hyperthermia applications [1] [4].

Semiconductor Nanoparticles: Quantum dots (QDs) such as cadmium selenide (CdSe) and zinc sulfide (ZnS) feature size-tunable fluorescence emission based on quantum confinement effects, making them powerful tools for bioimaging and biosensing [6].

Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNPs): Characterized by their highly ordered porous structures with pore diameters of 2-50 nm, providing substantial surface area for drug loading and functionalization [4].

Upconversion Nanoparticles (UCNPs): Typically composed of lanthanide-doped crystals that can convert near-infrared light to higher-energy UV or visible light, enabling deep-tissue imaging and light-triggered therapies [7].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Organic vs. Inorganic Nanoparticles

| Characteristic | Organic Nanoparticles | Inorganic Nanoparticles |

|---|---|---|

| Core Composition | Carbon-based molecules (phospholipids, polymers) | Metals, metal oxides, semiconductors, silica |

| Structural Features | Bilayer membranes (liposomes), branched architectures (dendrimers), polymeric matrices | Crystalline or amorphous structures, quantum confinement (QDs), porous frameworks (MSNPs) |

| Size Range | 10-200 nm (typically for drug delivery) | 1-100 nm (highly size-dependent properties) |

| Biodegradability | Generally biodegradable and biocompatible | Variable; some resistant to degradation (AuNPs), others soluble (IONPs) |

| Surface Functionalization | Covalent attachment or lipid conjugation | Thiol, amine, or carboxyl group conjugation; silica coating |

| Optical Properties | Limited intrinsic optical properties | Strong plasmonic resonance (Au, Ag), fluorescence (QDs), upconversion (UCNPs) |

| Magnetic Properties | Generally non-magnetic | Superparamagnetism (IONPs) |

| Typical Synthesis Approaches | Self-assembly, emulsion techniques, solvent evaporation | Chemical reduction, co-precipitation, sol-gel, green synthesis |

Toxicity Profiles: Mechanisms and Comparative Analysis

Understanding the toxicity mechanisms of nanoparticles is essential for their safe application in biomedicine. Both organic and inorganic nanoparticles exhibit distinct biological interactions that influence their toxicological profiles.

Organic Nanoparticle Toxicity Mechanisms

Organic nanoparticles generally demonstrate favorable biocompatibility profiles but can still elicit toxic responses under certain conditions:

Immune Recognition and Reactivity: While designed to be stealthy, some polymeric nanoparticles may trigger immune recognition through opsonization, leading to complement activation and subsequent inflammatory responses [6]. Surface properties, particularly charge, significantly influence this interaction, with cationic surfaces often exhibiting higher immunogenicity [2].

Oxidative Stress Induction: Despite being less pronounced than in inorganic nanoparticles, certain organic nanocarriers can induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation through intracellular interactions, potentially leading to oxidative damage to cellular components including lipids, proteins, and DNA [6].

Metabolic Byproducts: Biodegradable polymers breakdown into metabolic byproducts that may accumulate or cause local pH changes, potentially disrupting cellular homeostasis. The rate and nature of degradation products must be carefully evaluated for chronic applications [6].

Inorganic Nanoparticle Toxicity Mechanisms

Inorganic nanoparticles typically exhibit more complex and material-specific toxicity pathways:

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation: A primary toxicity mechanism for many inorganic nanoparticles involves the catalysis of ROS formation, including superoxide anion (O₂•⁻), hydroxyl radicals (•OH), and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) [2] [6]. Metal nanoparticles like silver and metal oxides such as ZnO and CuO are particularly potent ROS inducers through Fenton-like reactions and surface reactivity [2]. Excessive ROS production overwhelms cellular antioxidant defenses, leading to oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, protein denaturation, and DNA damage [2] [6].

Ion Release and Metal Toxicity: Many metallic nanoparticles undergo gradual dissolution in biological environments, releasing toxic ions that mediate cellular damage. For example, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) release Ag⁺ ions that bind to thiol groups in proteins and enzymes, disrupting mitochondrial function and electron transport chains [2]. Similarly, cadmium-based quantum dots release Cd²⁺ ions, which are highly toxic to cells [6].

Protein Corona Formation and Cellular Interactions: When introduced into biological fluids, nanoparticles rapidly adsorb proteins onto their surfaces, forming a "protein corona" that alters their biological identity and cellular interactions [6]. The composition of this corona influences cellular uptake, biodistribution, and immunological responses, potentially masking targeting functionalities intentionally placed on the nanoparticle surface [6].

Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Nanoparticles can localize to mitochondria, disrupting membrane potential, impairing ATP production, and promoting apoptosis through cytochrome c release [8] [6]. This is particularly documented for cationic nanoparticles that preferentially target the negatively charged mitochondrial membrane.

Genotoxicity and Epigenetic Alterations: Certain nanoparticles can directly or indirectly cause DNA damage through ROS-mediated oxidation, physical interaction with nuclear material, or interference with DNA repair mechanisms [2] [6]. This may lead to chromosomal aberrations, micronuclei formation, and alterations in gene expression patterns.

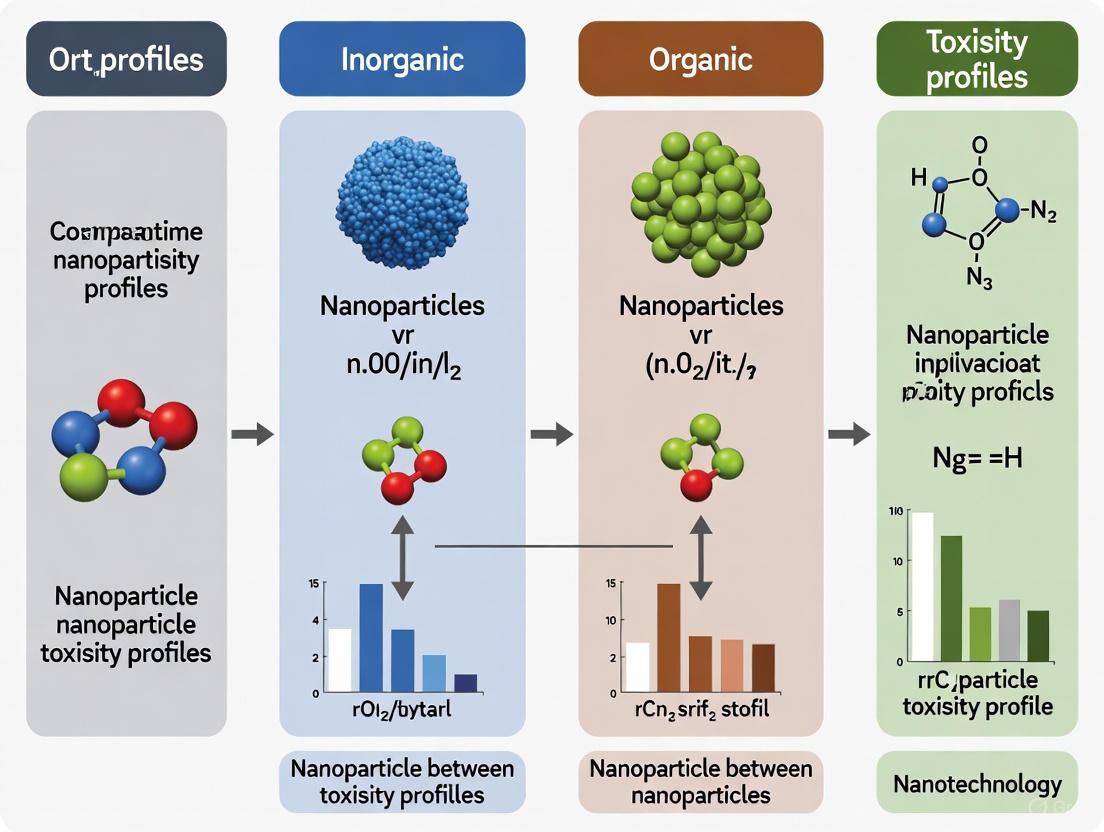

The following diagram illustrates the primary toxicity pathways shared by various nanoparticle types:

Figure 1: Primary toxicity mechanisms of nanoparticles at cellular and molecular levels

Factors Influencing Nanoparticle Toxicity

Multiple physicochemical parameters significantly influence nanoparticle toxicity profiles, regardless of their organic or inorganic classification:

Size: Smaller nanoparticles typically exhibit higher toxicity due to increased surface area-to-volume ratios, enhanced cellular uptake, and ability to penetrate biological barriers including the blood-brain barrier [2] [5]. Particles below 5.5 nm often undergo renal clearance, while larger particles accumulate in mononuclear phagocyte system organs (liver, spleen) [2].

Shape: Morphology affects cellular uptake mechanisms and toxicity; needle-like or high-aspect-ratio nanoparticles may cause physical membrane disruption, while spherical particles are generally internalized via endocytosis [2]. For instance, nanorod-shaped ZnO particles demonstrate higher toxicity to lung epithelial cells compared to spherical counterparts [2].

Surface Charge: Cationic nanoparticles typically exhibit greater cytotoxicity than anionic or neutral counterparts due to stronger electrostatic interactions with negatively charged cell membranes, enhancing cellular uptake and membrane disruption potential [2] [6].

Surface Chemistry and Functionalization: Surface modifications can dramatically alter toxicity profiles. PEGylation creates a steric barrier that reduces protein adsorption and opsonization, while targeting ligands may influence tissue-specific accumulation [2] [4].

Table 2: Physicochemical Parameters Affecting Nanoparticle Toxicity

| Parameter | Toxicity Influence | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Size | Smaller particles (<20 nm) generally more toxic due to higher reactivity and deeper tissue penetration | Particles <5.5 nm cleared renally; larger particles accumulate in liver/spleen [2] |

| Shape | High-aspect-ratio particles (rods, needles) may cause physical membrane damage | ZnO nanorods more toxic to lung cells than spherical particles [2] |

| Surface Charge | Cationic surfaces typically more toxic due to membrane interaction | Positively charged NPs show enhanced uptake and oxidative stress [2] |

| Chemical Composition | Metal ions leaching from NPs contribute significantly to toxicity | Ag⁺ ions from AgNPs bind to cellular thiol groups [2] |

| Surface Area | Higher surface area correlates with increased reactivity and ROS generation | NPs with larger surface area show greater bactericidal effects [1] |

| Solubility/Dissolution | Rate of dissolution affects ion release and persistence | More soluble metal oxides show higher acute toxicity [2] |

| Protein Corona | Alters cellular recognition, uptake, and biodistribution | Corona can mask targeting ligands on functionalized NPs [6] |

Experimental Methodologies for Toxicity Assessment

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for evaluating nanoparticle toxicity and generating comparable data across studies. The following section outlines key methodologies cited in current literature.

In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assessment

Cell culture studies represent the first tier of nanotoxicity evaluation due to advantages including cost-effectiveness, rapid results, ethical acceptability, and experimental control [6]. Standard protocols include:

Cell Viability Assays: MTT, XTT, and WST-1 assays measure mitochondrial reductase activity as an indicator of metabolic activity and cell viability. These colorimetric tests provide quantitative data on cytotoxicity but may suffer from interference with certain nanoparticles that directly reduce tetrazolium salts or absorb at measurement wavelengths [6]. Protocol: Seed cells in 96-well plates (5,000-10,000 cells/well), incubate for 24 hours, treat with nanoparticle suspensions across a concentration range (typically 0-200 μg/mL) for 24-72 hours, add MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL), incubate 2-4 hours, dissolve formazan crystals with DMSO, and measure absorbance at 570 nm with reference at 630-690 nm [6].

Membrane Integrity Assays: Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release quantifies plasma membrane damage by measuring the cytoplasmic enzyme LDH in cell culture supernatants. Protocol: Collect supernatant from nanoparticle-treated cells, incubate with NADH and pyruvate in appropriate buffer, and measure absorbance decrease at 340 nm due to NADH oxidation [6].

Oxidative Stress Detection: Dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) assay measures intracellular ROS production. The non-fluorescent DCFH-DA diffuses into cells where intracellular esterases remove the diacetate group, and subsequent oxidation by ROS produces fluorescent DCF. Protocol: Load cells with 10-20 μM DCFH-DA for 30 minutes, treat with nanoparticles, and measure fluorescence at 485 nm excitation/535 nm emission [6].

Genotoxicity Assessment: Comet assay (single-cell gel electrophoresis) detects DNA strand breaks at the individual cell level. Protocol: Embed nanoparticle-treated cells in low-melting-point agarose on microscope slides, lyse cells to remove membranes and proteins, electrophorese under alkaline conditions, stain with DNA-binding fluorescent dye, and analyze for DNA migration patterns [6].

In Vivo Toxicity Evaluation

Animal studies provide critical information on biodistribution, accumulation, and systemic toxicity:

Biodistribution Studies: Utilize radiolabeled or fluorescently tagged nanoparticles to track tissue distribution over time. Typically performed in rodents via various administration routes (intravenous, oral, inhalation) with subsequent tissue collection and analysis at predetermined time points [6]. Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) provides quantitative elemental analysis for metal-based nanoparticles.

Histopathological Examination: Systematic microscopic evaluation of tissue sections from major organs (liver, spleen, kidneys, lungs, brain) after necropsy to identify nanoparticle-induced lesions, inflammation, fibrosis, or other pathological changes [8] [6].

Hematological and Biochemical Analysis: Blood collection for complete blood count, differential white cell analysis, and plasma biochemistry markers of organ function (liver enzymes, renal function parameters) to detect systemic toxicity [6].

Immunotoxicity Assessment: Flow cytometric analysis of immune cell populations, cytokine profiling, and evaluation of hypersensitivity responses to identify immunomodulatory effects [8].

The following workflow diagram outlines a comprehensive nanoparticle toxicity assessment strategy:

Figure 2: Comprehensive toxicity assessment workflow for nanoparticles

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogizes critical reagents, materials, and experimental systems employed in nanoparticle toxicity research, as referenced in the current literature:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Systems for Nanoparticle Toxicity Studies

| Reagent/System | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Line Models | In vitro toxicity screening | Human lung epithelial cells (A549), liver hepatocytes (HepG2), macrophages (THP-1), and primary cells for tissue-specific responses [6] |

| MTT/XTT/WST-1 Assays | Cell viability and metabolic activity assessment | Tetrazolium salt reduction measured spectrophotometrically; mitochondrial function indicator [6] |

| DCFH-DA Probe | Intracellular ROS detection | Fluorescence-based measurement of oxidative stress; excitation/emission at 485/535 nm [6] |

| LDH Assay Kit | Membrane integrity assessment | Quantifies lactate dehydrogenase release from damaged cells [6] |

| Comet Assay Reagents | DNA damage evaluation | Alkaline electrophoresis for detection of single-strand breaks in individual cells [6] |

| Animal Models | In vivo toxicity and biodistribution | Rodent models (mice, rats) for systemic toxicity assessment [8] [6] |

| ICP-MS | Quantitative elemental analysis | Detection and quantification of metal-based nanoparticles in biological tissues [6] |

| Dynamic Light Scattering | Hydrodynamic size and zeta potential | Particle size distribution and surface charge measurement in suspension [2] |

| Protein Corona Analysis | Characterization of bio-nano interactions | SDS-PAGE, mass spectrometry to identify adsorbed proteins [6] |

The comparative analysis of organic and inorganic nanoparticles reveals distinct advantages and limitations that inform their selection for specific biomedical applications. Organic nanoparticles, particularly liposomes and polymeric NPs, generally offer superior biocompatibility and biodegradability with established regulatory approval pathways, as evidenced by FDA-approved formulations like Doxil [4]. Their tunable release kinetics and functionalization capabilities make them particularly suitable for drug delivery applications where long-term safety is paramount. However, they often lack the inherent functionality for imaging and external activation possessed by many inorganic nanoparticles.

Inorganic nanoparticles provide unique physical properties—including magnetic responsiveness (IONPs), plasmonic characteristics (AuNPs), and fluorescent emissions (QDs)—that enable multifunctional applications in imaging, diagnostics, and triggered therapies [7] [4]. These advantages come with increased toxicological concerns, particularly regarding ion leaching, ROS generation, and long-term persistence in biological systems. Their toxicity profiles are highly dependent on specific physicochemical parameters including size, shape, surface chemistry, and coating strategies.

The emerging paradigm in nanomedicine involves combining the advantages of both material classes through hybrid approaches, such as inorganic nanoparticles encapsulated in organic coatings or organic-inorganic composite systems. These strategies aim to mitigate toxicity while preserving functionality. Future research directions should prioritize systematic structure-activity relationship studies, long-term fate investigations, and standardized toxicity assessment protocols to enable rational design of safer nanoparticles. As the field advances, the strategic selection between organic and inorganic platforms will continue to depend on a balanced consideration of therapeutic objectives, imaging requirements, and acceptable risk-benefit profiles tailored to specific clinical applications.

The expanding application of nanoparticles (NPs) in fields like medicine, consumer goods, and electronics necessitates a thorough understanding of their toxicological profiles [9] [10]. For researchers and drug development professionals, predicting and mitigating nanotoxicity is paramount for designing safer nanomedicines and products. The toxicity of NPs is not a function of a single parameter but is governed by a complex interplay of key physicochemical properties: size, shape, surface charge, and composition [11]. Furthermore, a fundamental distinction in nanotoxicology lies in the classification of NPs as organic or inorganic, as their core material dictates their basic biological interactions and persistence [12]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how these properties influence the toxicity of organic and inorganic NPs, supported by experimental data and methodologies.

Comparative Analysis of Key Physicochemical Properties

The following sections and tables detail how each physicochemical property influences NP toxicity, with specific comparisons between organic and inorganic NPs.

Nanoparticle Size

Size directly influences cellular uptake, biodistribution, and the surface area available for biological interactions. Smaller NPs (typically < 20 nm) generally exhibit greater toxicity due to their ability to penetrate cellular barriers, access subcellular compartments, and generate higher reactive oxygen species (ROS) per unit mass [11].

Table 1: Impact of Nanoparticle Size on Toxicity

| NP Type | Specific NP | Size Compared | Experimental Model | Key Toxicological Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic | Gold (Au) [11] | 2, 6, 10, 16 nm | MCF-7 breast cancer cells | NPs <10 nm internalized into the cell nucleus; larger NPs remained in the cytoplasm. |

| Inorganic | Silver (Ag) [11] | 10, 40, 100 nm | In vivo (mice) | 10 nm NPs had higher tissue distribution and more severe hepatobiliary toxicity. |

| Inorganic | Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) [11] | 6, 12, 15 nm | Zebrafish embryos | 6 nm NPs caused more oxidative stress and DNA damage under illumination. |

| Inorganic | Silver (Ag) [10] | 10 nm | In vivo (mice) | Smaller NPs improve tissue distribution and increase hepatobiliary toxicity. |

| General | Not Specified [13] | Smaller vs. Larger | Machine Learning Model | Smaller NPs have heightened toxicity due to larger surface-to-volume ratios. |

Nanoparticle Shape

The shape of a NP affects its kinetics of cellular uptake, circulation time in the body, and the nature of its interaction with cellular membranes [11].

Table 2: Impact of Nanoparticle Shape on Toxicity

| NP Type | Shape Compared | Experimental Model / Basis | Key Toxicological Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| General | Spheres, rods, sheets, cubes [11] | Computational & Cellular Studies | Non-spherical NPs (e.g., rods, sheets) are internalized faster and in larger amounts than spherical NPs. |

| General | Spheres vs. Non-spherical [11] | In vivo biodistribution studies | Non-spherical NPs can have longer blood circulation time and higher accumulation in specific organs. |

Surface Charge and Chemistry

Surface charge, often indicated by zeta potential, governs the electrostatic interactions between NPs and negatively charged cell membranes. While cationic (positively charged) NPs are generally associated with higher toxicity and cellular uptake, recent evidence suggests surface charge density is a more precise predictor than zeta potential alone [14] [11].

Table 3: Impact of Surface Charge on Toxicity

| NP Type | Surface Property Tested | Experimental Model | Key Toxicological Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic (Carbon Dots) | Surface charge density [14] | THP-1 macrophages, A549/Calu-3 cells, mice | Cationic NPs with high surface charge density (Qek > 2.95 µmol/g) induced oxidative stress, IL-8 release, and airway inflammation. NPs with low density did not. |

| Organic (Carbon Dots) | Zeta potential [14] | THP-1 macrophages | Five cationic NPs with similar ζ-potential (+20 to +27 mV) showed vastly different toxicity, correlated with charge density, not ζ-potential. |

| General | Cationic vs. Anionic [14] | Literature Review | A positive ζ-potential is often associated with greater toxicity due to strong electrostatic interaction with cell membranes. |

Chemical Composition

The core material of a NP determines its intrinsic chemical reactivity, solubility, and potential for ion release, which are primary drivers of toxicity. This property fundamentally differentiates organic and inorganic NPs [12].

Table 4: Impact of Chemical Composition on Toxicity (Organic vs. Inorganic)

| NP Class | Composition Examples | Key Toxicological Mechanisms | Notes on Persistence & Biodegradation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic | Metal (Ag, Au) [11], Metal Oxides (ZnO, TiO₂, SiO₂) [9] | ROS generation via Fenton-like reactions, release of toxic ions (e.g., Ag⁺, Zn²⁺), permanent catalytic activity, oxidative stress [9] [11]. | Generally more persistent in the environment and biological systems; can undergo transformation (e.g., sulfidation) [15]. |

| Organic | Polymers (PLGA), Lipids, Dendrimers [12] | Interaction with cellular membranes, disruption of lipid bilayers, inflammation from degradation products [16]. | Typically biodegradable and less persistent; toxicity is often more dependent on surface functionalization [12] [16]. |

Experimental Protocols for Toxicity Assessment

To generate the data cited above, standardized experimental protocols are employed. Below are detailed methodologies for key tests.

1In VitroCytotoxicity and Mechanistic Assays

- Cell Culture: Use relevant cell lines (e.g., THP-1-derived macrophages, A549 or Calu-3 airway epithelial cells) [14]. Maintain cells in appropriate media and culture conditions.

- NP Exposure:

- Viability Assessment:

- Perform MTT or MTS assay. This measures mitochondrial activity by the reduction of tetrazolium salts to formazan dyes. Add reagent to wells after NP exposure, incubate, and measure absorbance. Viability is expressed as a percentage of the untreated control [14].

- Oxidative Stress Measurement:

- Use a fluorescent probe, such as H2DCFDA. After NP exposure, load cells with the probe, which is oxidized by intracellular ROS to a fluorescent product. Quantify fluorescence using a plate reader or flow cytometry [14].

- Inflammatory Response:

- Collect cell culture supernatant after NP exposure.

- Measure the concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines like Interleukin-8 (IL-8) using an Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kit according to the manufacturer's protocol [14].

- Cellular Uptake:

- For fluorescent NPs (e.g., carbon dots), use Flow Cytometry (FACS) or Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM). For FACS, trypsinize and analyze cells to quantify fluorescence intensity. For CLSM, fix cells and image to visualize NP localization [14].

2In VivoPulmonary Toxicity Assessment

- Animal Model: Use specific pathogen-free mice (e.g., C57BL/6) [14].

- NP Administration:

- Anesthetize mice.

- Administer a single dose of NPs (e.g., 50 µg in 50 µL of saline) via oropharyngeal aspiration. A control group receives saline only [14].

- Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL) and Analysis:

- At a set endpoint (e.g., 24 hours post-exposure), euthanize the animals.

- Cannulate the trachea and lavage the lungs with sterile saline.

- Centrifuge the BAL fluid (BALF). The supernatant can be used for cytokine analysis (e.g., ELISA).

- Resuspend the cell pellet and perform total cell counts. Prepare cytospin slides, stain (e.g., with Diff-Quick), and perform differential cell counts (macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes) under a microscope to quantify airway inflammation [14].

Visualization of Key Toxicity Pathways

The following diagram integrates the properties discussed into a common pathway for NP-induced toxicity, highlighting the central role of oxidative stress.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This table lists key materials and tools used in the featured experiments for studying nanoparticle toxicity.

Table 5: Research Reagent Solutions for Nanotoxicity Studies

| Item | Function / Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| THP-1 Cell Line | Human monocytic cell line that can be differentiated into macrophage-like cells. A key model for immune response and phagocytosis studies. | Assessing NP uptake, cytotoxicity, and inflammatory cytokine release in immune cells [14]. |

| A549 / Calu-3 Cell Lines | Human lung epithelial cell lines. Representative models for the respiratory tract, a primary exposure route. | Evaluating cytotoxicity and barrier function disruption in the lung [14]. |

| MTT / MTS Assay Kits | Colorimetric assays that measure the metabolic activity of cells, serving as an indicator of cell viability and proliferation. | Quantifying NP-induced cytotoxicity in vitro [14]. |

| H2DCFDA Fluorescent Probe | Cell-permeable dye that becomes fluorescent upon oxidation by reactive oxygen species (ROS). | Detecting and quantifying intracellular oxidative stress triggered by NPs [14]. |

| ELISA Kits (e.g., for IL-8) | Immunoassay kits for the precise quantification of specific proteins or cytokines in a sample. | Measuring the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in cell culture supernatant or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) [14]. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Instrumentation to measure the hydrodynamic size distribution and aggregation state of NPs in suspension. | Characterizing the stability and size profile of NPs in biological media [14]. |

| Zeta Potential Analyzer | Instrumentation to measure the surface charge (electrostatic potential) of NPs in suspension. | Determining NP surface charge, a key property influencing colloidal stability and cellular interaction [14]. |

The expanding application of nanoparticles (NPs) in biotechnology, medicine, and consumer products has necessitated a thorough understanding of their biological interactions and toxicological profiles [17]. Engineered nanomaterials (NMs), defined as materials with at least one external dimension between 1-100 nm, exhibit unique physicochemical properties that differ markedly from their bulk counterparts [5]. These very properties—small size, large surface area-to-volume ratio, and enhanced reactivity—that make NPs technologically valuable also raise concerns about their potential adverse effects on human health and the environment [17] [18]. When NPs enter biological systems, they can initiate a cascade of molecular events at the cellular level, primarily through induction of oxidative stress, inflammation, genotoxicity, and apoptosis [17] [19]. Understanding these fundamental mechanisms is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working toward the safe implementation of nanotechnologies. This review systematically compares the toxicity mechanisms of inorganic versus organic nanoparticles, providing experimental methodologies, key signaling pathways, and essential research tools for investigating nanomaterial toxicity.

Comparative Toxicity Mechanisms of Inorganic and Organic Nanoparticles

The table below summarizes the primary toxicity mechanisms associated with major classes of inorganic and organic nanoparticles, based on current literature:

Table 1: Comparative Toxicity Profiles of Selected Nanoparticles

| Nanoparticle Type | Oxidative Stress | Inflammation | Genotoxicity | Apoptosis | Key Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Oxide (ZnO) | High [18] | Moderate [18] | High [18] | High [18] | Dissolution releasing Zn²⁺ ions; ROS generation; mitochondrial dysfunction [17] [18] |

| Metal Oxide (TiO₂) | Moderate [19] | Moderate [19] | Moderate [19] | Moderate [19] | Photocatalytic ROS generation; DNA strand breaks; inflammatory cytokine activation [19] |

| Metal (Silver) | High [18] | High [18] | High [18] | High [18] | ROS generation; LDH leakage; DNA adduct formation; membrane damage [18] |

| Metal (Gold) | Low [18] | Low [18] | Low [18] | Low [18] | Generally inert; toxicity dependent on surface functionalization [18] |

| Carbon-Based (CNT) | High [17] | High [17] | Moderate [17] | High [17] | Mitochondrial damage; fiber-like pathogenicity; proinflammatory cytokine release [17] |

| Polymeric (Chitosan) | Low [5] | Low [5] | Low [5] | Low [5] | Generally biocompatible and biodegradable [5] |

The toxicity of nanoparticles is governed by multiple physicochemical parameters including size, shape, surface charge, coating, and chemical composition [5]. Smaller nanoparticles typically exhibit greater toxicity due to their increased surface area-to-volume ratio and enhanced reactivity [17] [20]. Surface coatings play a crucial role in modulating nanoparticle behavior; for instance, polyethylene glycol (PEG) coatings can reduce toxicity by stabilizing dispersion and altering bioavailability [20]. Inorganic metal and metal oxide nanoparticles often exert toxicity through ion release and Fenton-type reactions that generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) [17], while carbon-based materials may cause physical membrane damage and oxidative stress via mitochondrial disruption [17].

Key Cellular Toxicity Mechanisms

Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress represents a primary mechanism of nanoparticle-induced toxicity, resulting from an imbalance between ROS production and the biological system's ability to detoxify these reactive intermediates [17]. NPs can generate ROS through several pathways: (1) prooxidant functional groups on reactive surfaces; (2) active redox cycling on transition metal-based NP surfaces; and (3) particle-cell interactions that disturb cellular components [17]. The hierarchical model of oxidative stress illustrates cellular responses to increasing levels of ROS: at mild oxidative stress levels, cells activate phase II antioxidant enzymes via Nrf2 induction; intermediate levels trigger proinflammatory responses through MAPK and NF-κB signaling; while severe oxidative stress causes mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death [17]. Metal-based nanoparticles like copper, iron, and silver can catalyze Fenton-type and Haber-Weiss reactions, generating highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (OH•) that damage cellular components [17].

Inflammation

NP-induced oxidative stress often functions as a torchbearer for inflammatory responses [17]. Inflammatory cells such as macrophages and neutrophils can become activated upon exposure to NPs, leading to increased production of ROS and proinflammatory cytokines [17]. Signaling pathways including nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades become activated, resulting in the increased expression of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-8 (IL-8) [17] [19]. Chronic inflammation induced by nanoparticles can lead to more severe pathological conditions including fibrosis, granuloma formation, and tissue damage [17].

Genotoxicity

Nanoparticles can cause damage to genetic material through both direct and indirect mechanisms [19]. Direct genotoxicity may occur when NPs or their dissolved ions physically interact with DNA, causing strand breaks, cross-links, or base modifications [19]. Indirect genotoxicity can result from oxidative stress-induced DNA damage or from interference with DNA repair mechanisms [17]. The comet assay (single-cell gel electrophoresis) is frequently employed to detect DNA strand breaks, while micronucleus tests and chromosomal aberration assays identify chromosomal damage [18] [19]. Studies have demonstrated that co-exposure to multiple toxicants, such as TiO₂ nanoparticles and acrylamide, can synergistically enhance genotoxic effects, resulting in increased DNA strand breaks in brain tissues of experimental models [19].

Apoptosis

NP-induced oxidative stress and DNA damage can trigger programmed cell death through apoptotic pathways [19]. This process involves the upregulation of tumor suppressor protein p53, activation of caspase cascades, and characteristic DNA fragmentation [19]. Studies with TiO₂ nanoparticles have shown increased expression of apoptotic genes including P53, TNF-α, IL-6, and Presenillin-1 in neural tissues [19]. The laddered DNA fragmentation assay is commonly used to detect the internucleosomal DNA cleavage patterns characteristic of apoptosis [19]. The extent of apoptotic induction varies significantly among different nanoparticle types, with more reactive materials like silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles typically causing greater apoptotic responses compared to relatively inert nanoparticles like gold or certain polymeric NPs [18].

Experimental Protocols for Toxicity Assessment

Assessing Oxidative Stress

Intracellular ROS Measurement using DCFH-DA Assay The fluorescent probe 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) is widely used to detect intracellular ROS generation [19]. The non-fluorescent DCFH-DA passively enters cells, where intracellular esterases remove the diacetate group, trapping the non-fluorescent DCFH within cells. ROS oxidize DCFH to the highly fluorescent compound DCF, which can be quantified.

Protocol:

- Culture cells in appropriate medium and seed in multi-well plates at optimal density

- Expose cells to nanoparticles at various concentrations for selected time points

- Remove medium and wash cells with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Incubate cells with DCFH-DA (10-20 μM in serum-free medium) for 30 minutes at 37°C in the dark

- Remove DCFH-DA solution and wash cells with PBS

- Measure fluorescence intensity using fluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry, or microplate reader (excitation 485 nm, emission 535 nm)

- Include appropriate controls: untreated cells (background), positive control (e.g., H₂O₂-treated cells)

Evaluating Genotoxicity

Alkaline Comet Assay for DNA Strand Breaks The alkaline comet assay (single-cell gel electrophoresis) detects DNA single- and double-strand breaks at the individual cell level [19].

Protocol:

- Prepare cell suspension from treated tissue or cell culture (approximately 10,000 cells)

- Mix cells with 0.5% low melting point agarose and layer onto pre-coated slides

- Immerse slides in cold lysis buffer (2.5 M NaCl, 100 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris, 1% Triton X-100, 10% DMSO; pH 10) for at least 1 hour at 4°C

- Place slides in alkaline electrophoresis buffer (300 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA; pH >13) for 20-40 minutes to allow DNA unwinding

- Perform electrophoresis at 25 V, 300 mA for 20-30 minutes

- Neutralize slides with Tris buffer (0.4 M Trizma base; pH 7.5) and stain with DNA-binding dye (e.g., ethidium bromide, SYBR Green)

- Analyze using fluorescence microscopy; quantify DNA damage using parameters like tail length, % DNA in tail, and tail moment with specialized software

Detecting Apoptosis

DNA Laddering Assay Apoptotic cells exhibit characteristic internucleosomal DNA cleavage, producing a "ladder" pattern when separated by agarose gel electrophoresis [19].

Protocol:

- Homogenize tissue samples or collect cultured cells

- Lyse samples in Tris-EDTA buffer containing 0.5% SDS and 0.5 mg/mL RNase A; incubate at 37°C for 1 hour

- Add proteinase K (0.2 mg/mL) and incubate at 50°C overnight

- Extract DNA using phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol mixture

- Precipitate DNA with ethanol and resuspend in TE buffer

- Quantify DNA concentration and load equal amounts (0.5-1 μg) on 1.5-2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide

- Perform electrophoresis at 70-80 V for 1-2 hours

- Visualize DNA fragmentation pattern using UV transilluminator; apoptotic samples show characteristic ~180-200 bp laddering

Signaling Pathways in Nanoparticle Toxicity

The following diagrams illustrate key signaling pathways involved in nanoparticle-induced toxicity, created using Graphviz DOT language:

Cellular Response Pathways to Nanoparticle-Induced Oxidative Stress

Comprehensive Toxicity Assessment Methodology

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Nanoparticle Toxicity Research

| Reagent/Chemical | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DCFH-DA | Detection of intracellular ROS | Fluorescent probe oxidized by ROS to DCF; used in various cell types [19] |

| MTT/MTS/WST-1 | Cell viability and metabolic activity assays | Tetrazolium-based assays; measure mitochondrial function [18] |

| LDH Assay Kit | Cell membrane integrity assessment | Measures lactate dehydrogenase release upon membrane damage [18] |

| ELISA Kits | Quantification of cytokines and biomarkers | Detect TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8 and other inflammatory mediators [21] |

| Comet Assay Reagents | Detection of DNA strand breaks | Low melting point agarose, lysis buffers, fluorescent DNA dyes [19] |

| Apoptosis Detection Kits | Identification of apoptotic cells | Annexin V/propidium iodide staining; caspase activity assays [19] |

| Antioxidant Assays | Measurement of oxidative stress markers | Kits for GSH, SOD, CAT, GPx, lipid peroxidation products [17] [21] |

| qPCR Reagents | Gene expression analysis | Primers for p53, TNF-α, IL-6, Presenillin-1 and other relevant genes [19] |

The cellular mechanisms underlying nanoparticle toxicity involve complex, interconnected pathways centered around oxidative stress, inflammation, genotoxicity, and apoptosis. Inorganic nanoparticles, particularly metal and metal oxide varieties, often exhibit higher toxicity compared to their organic counterparts, primarily due to their ability to generate ROS via Fenton-type reactions and release toxic ions [17] [18]. The physicochemical properties of nanoparticles—size, shape, surface chemistry, and coating—critically influence their biological interactions and toxic potential [5] [20]. Comprehensive toxicity assessment requires integrated methodological approaches spanning ROS detection, genotoxicity evaluation, inflammatory response measurement, and cell death analysis. As nanotechnology continues to advance, understanding these fundamental toxicity mechanisms becomes increasingly important for the rational design of safer nanomaterials and for accurate risk assessment in both pharmaceutical development and environmental health contexts. Future research should focus on long-term exposure effects, interactions between different nanoparticle types, and the development of standardized testing protocols that better reflect realistic exposure scenarios.

The Role of Surface Chemistry and Functionalization in Biocompatibility and Cellular Interactions

In the field of nanomedicine and biomaterials, the interface between a synthetic material and a biological system is of paramount importance. The surface of a nanoparticle or implantable device is the primary site of interaction with proteins, cells, and tissues, ultimately determining the biological response and therapeutic efficacy. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding how surface chemistry and functionalization influence biocompatibility and cellular interactions is crucial for designing effective biomedical products. This guide provides a comparative examination of how surface properties govern biological responses, with particular attention to the distinct toxicity profiles of inorganic versus organic nanoparticles, supported by experimental data and methodologies.

Surface properties—including chemical composition, charge, hydrophobicity, and specific functional groups—directly dictate the amount, composition, and conformational changes of proteins that adsorb to the material within biological fluids. This initial layer of adsorbed proteins then mediates all subsequent cellular interactions, including inflammatory responses, uptake efficiency, and overall biocompatibility [22]. The ability to engineer surface characteristics through various modification techniques therefore provides a powerful strategy for controlling material-tissue interactions and improving clinical outcomes.

Surface Properties Governing Biocompatibility

Key Physicochemical Properties and Their Biological Impact

The table below summarizes the major surface properties that critically influence biocompatibility and cellular responses, based on extensive experimental observations.

Table 1: Key Surface Properties and Their Biological Impact

| Surface Property | Biological Impact | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Charge (Zeta Potential) | Positively charged surfaces typically enhance cellular uptake but may increase toxicity and protein adsorption. Negatively charged or neutral surfaces often prolong circulation time but may reduce cellular internalization [23]. | Pdots-NH₂ (+3.73 mV) showed 80% cell viability vs. ~90% for Pdots-COOH (-18 mV) at 60 μg/mL in CaSki, 4T1, and BEAS-2B cell lines [24]. |

| Hydrophobicity/ Hydrophilicity | Hydrophilic surfaces generally reduce non-specific protein adsorption and improve biocompatibility. Hydrophobic surfaces tend to promote protein adsorption, often inducing conformational changes that expose inflammatory epitopes [22]. | Hydrophobic biomaterials show progressive, time-dependent conformational changes in adsorbed fibrinogen, exposing Receptor-Induced Binding Sites (RIBS) and increasing resistance to SDS elution [22]. |

| Surface Functional Groups | Specific terminal groups (e.g., -COOH, -NH₂, -OH) directly influence protein binding, cell adhesion, and inflammatory responses. Carboxyl and hydroxyl groups often improve biocompatibility compared to amine groups [22]. | Self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) with controlled functionalities demonstrate that surface chemistry directly influences the extent of foreign body reactions in vivo [22]. |

| Surface Topography & Roughness | Nanoscale roughness and patterns can direct cell alignment, migration, and differentiation (e.g., osteogenesis on rougher surfaces) [25]. | Sandblasting and acid etching of titanium implants create micro- and nano-roughness that enhances bone integration and mechanical interlocking [25]. |

The Protein Adsorption Cascade

The initial moments after a biomaterial is introduced to a biological environment are critical. Within minutes to hours, a layer of host proteins adsorbs onto the surface, a process governed by the material's surface properties [22]. The composition and, more importantly, the conformation of these adsorbed proteins then dictate all subsequent biological responses.

Hydrophobic surfaces, common in many conventional biomaterials, have a high affinity for a wide range of proteins like fibrinogen, albumin, and IgG. Upon adsorption to these surfaces, proteins often undergo conformational changes, exposing hydrophobic domains and cryptic inflammatory epitopes that are normally hidden in their native state [22]. For instance, adsorbed fibrinogen exposes RIBS epitopes (e.g., gamma112-119 and Aα 95-98), which serve as recognition sites for inflammatory cells like macrophages, thereby initiating a foreign body reaction [22].

The following diagram illustrates this critical sequence of events triggered by material surface properties.

Surface Modification Techniques and Functionalization

A variety of physical, chemical, and coating techniques have been developed to engineer material surfaces and elicit desired biological responses.

Table 2: Surface Modification and Functionalization Techniques

| Technique Category | Specific Methods | Key Mechanism & Outcome | Considerations for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Methods | Plasma treatment, UV irradiation, Sandblasting [25] | Alters surface energy, introduces functional groups, creates micro/nano-topography without changing bulk chemistry. Plasma treatment can increase hydrophilicity. | Requires specialized equipment. Surface activation can be temporary (ageing effect). Excellent for controlling topography. |

| Chemical Methods | Chemical grafting, SAMs, Silanization, Oxidation [22] [25] | Covalently attaches specific functional groups (e.g., -NH₂, -COOH) or polymer chains (e.g., PEO) to the surface. Provides stable, well-defined coatings. | SAMs limited to gold/silver-coated surfaces [22]. Risk of toxic monomer residues in chemical grafting. |

| Coating & Immobilization | Layer-by-layer (LbL), Dip coating, Grafting ("to" or "from"), PEGylation [25] [23] | Applies thin layers of materials or bioactive molecules. PEGylation creates a "stealth" effect, reducing opsonization and extending circulation half-life [23]. | Bioactivity of immobilized molecules (e.g., peptides, antibodies) can depend on orientation and density. |

| Biofunctionalization | Immobilization of peptides (RGD), proteins, growth factors (VEGF, BMP-2) [25] | Confers specific bioactivity to direct cell behavior (e.g., adhesion, differentiation). RGD peptides promote integrin-mediated cell attachment. | Requires covalent chemistry (EDC/NHS) or affinity-based systems (biotin-streptavidin). Stability and presentation are critical. |

Comparative Toxicity: Inorganic vs. Organic Nanoparticles

The core material of a nanoparticle—whether inorganic or organic—imparts fundamental differences in its toxicity profile and mechanisms. Understanding these differences is essential for selecting the appropriate nanoplatform for a given biomedical application.

Toxicity Mechanisms and Influencing Parameters

Table 3: Comparative Toxicity Profiles of Inorganic vs. Organic Nanoparticles

| Parameter | Inorganic Nanoparticles | Organic Nanoparticles |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Materials | Metals (Ag, Au), Metal Oxides (TiO₂, ZnO), Quantum Dots, Silica [26] [5]. | Polymeric NPs (PLGA), Lipids, Dendrimers, Conjugated Polymer NPs (Pdots) [5] [23]. |

| Dominant Toxicity Mechanisms | - Ion release (e.g., Ag⁺, Zn²⁺) [5].- Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) [5].- Direct membrane damage and organelle interaction. | - Incompatible or degradable material [23].- Interaction-based toxicity due to small size and large surface area [23].- Elicitation of adverse immune responses. |

| Key Structural Parameters Affecting Toxicity | Size, shape, crystal structure, agglomeration state, dissolution rate, surface charge, and chemical composition [5]. | Molecular weight, polymer composition, degradation profile, surface charge, and hydrophobicity [23]. |

| Surface Modification Impact | Crucial for mitigating toxicity. Coating with silica, polymers (PEG), or biomolecules (albumin) can reduce ion leaching and ROS generation [27] [28]. | Surface decoration is key to improving biocompatibility. PEGylation prevents protein adsorption; targeting ligands reduce off-target effects and required dose [23]. |

| Experimental Evidence | Metal/Metal Oxide NPs (e.g., Ag, ZnO) often show higher toxicity compared to their ionic counterparts, linked to particle-specific effects and ROS [5] [29]. | Systematic study on Pdots showed Pdots-NH₂ (cationic) had higher cytotoxicity and lower stability than anionic Pdots-COOH or Pdots-SH [24]. |

Experimental Data from Surface-Modified Pdots

A systematic investigation into semiconducting polymer nanoparticles (Pdots) with different surface modifications provides quantitative data on how functional groups influence properties and biocompatibility.

Table 4: Experimental Data for Surface-Functionalized Pdots [24]

| Pdot Type | Zeta Potential (mV) | PDI (Stability Indicator) | Cell Viability (at 60 μg/mL) | In Vivo Circulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pdots@COOH | -18.0 | Low (~0.1) | ~90% (CaSki, 4T1, BEAS-2B) | Superior |

| Pdots@SH | -18.0 | Low (~0.1) | ~90% (CaSki, 4T1, BEAS-2B) | Superior |

| Bare Pdots | -16.3 | Low (~0.1) | ~90% (CaSki, 4T1, BEAS-2B) | Good |

| Pdots@NH₂ | +3.7 | High (>0.2) | ~80% (CaSki, 4T1, BEAS-2B) | Poor |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers designing experiments to evaluate surface chemistry and biocompatibility, the following toolkit is essential.

Table 5: Research Reagent Solutions for Surface and Biocompatibility Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Aminosilanes (e.g., APTES) | Introduces primary amine (-NH₂) groups onto silica and metal oxide surfaces for further bioconjugation [27]. | Creating positively charged surfaces to study the effect of charge on protein adsorption and cell adhesion. |

| Thio-Carboxylic Acids | Bifunctional crosslinker for noble metal NPs (Au, Ag); thiol group binds metal, carboxyl group allows ligand attachment [27] [28]. | Functionalizing gold nanoparticles with carboxylic acids for covalent coupling to antibodies or peptides. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | "Stealth" polymer; creates a hydrophilic, steric barrier that reduces protein adsorption (opsonization) and immune clearance [23]. | PEGylating liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) to prolong circulation half-life and enhance tumor accumulation via EPR. |

| DSPE-PEG-R Polymers | Amphiphilic polymers for nanoparticle functionalization; DSPE anchors in lipid membranes, PEG provides a spacer, R (e.g., -COOH, -NH₂) is the functional terminal group [24]. | Synthesizing surface-functionalized Pdots or liposomes with specific targeting ligands via carboxyl or amine chemistry. |

| EDC / NHS Chemistry | Zero-length crosslinkers for catalyzing covalent bond formation between carboxyl and amine groups. | Immobilizing RGD peptides on carboxyl-functionalized surfaces to promote specific integrin-mediated cell adhesion. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessing Conformational Changes of Adsorbed Fibrinogen

This protocol is fundamental for evaluating the bioactivity of a material surface based on its interaction with a key blood protein [22].

- Surface Preparation: Create model surfaces with defined chemistry (e.g., using SAMs on gold or plasma-treated polymers). Characterize surface properties (wettability, charge) via contact angle goniometry and zeta potential.

- Protein Adsorption: Incubate surfaces with a solution of purified human fibrinogen (e.g., 1 mg/mL in PBS, pH 7.4) for a set period (e.g., 1-4 hours) at 37°C.

- SDS Elution Resistance Assay:

- After incubation, gently wash the surfaces with buffer to remove non-adherent protein.

- Treat the surfaces with a 1% SDS solution (a strong ionic detergent) for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Collect the eluted proteins and quantify the remaining, tightly bound fibrinogen on the surface using a technique like scanning angle reflectometry or by staining and eluting for spectrophotometric measurement.

- Data Interpretation: A higher percentage of SDS-resistant fibrinogen indicates stronger, more denatured protein adhesion, which is correlated with increased inflammatory potential [22].

Protocol: Evaluating Cytotoxicity of Surface-Modified Nanoparticles (CCK-8 Assay)

This standard colorimetric assay measures cell metabolic activity as an indicator of cytotoxicity [24].

- Cell Seeding: Seed appropriate cell lines (e.g., cancer cell lines like 4T1 or primary cells relevant to the application) in a 96-well plate at a density of ~5,000-10,000 cells/well. Culture for 24 hours to allow cell attachment.

- Nanoparticle Exposure: Prepare a dilution series of the surface-modified nanoparticles (e.g., 0, 10, 20, 40, 60 μg/mL) in cell culture medium. Replace the medium in the wells with the nanoparticle-containing medium. Include wells with medium only (blank) and cells with medium only (control).

- Incubation: Incubate the plate for 24-48 hours at 37°C and 5% CO₂.

- Viability Measurement:

- Add 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent to each well.

- Incubate the plate for 1-4 hours at 37°C.

- Measure the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

- Data Analysis: Calculate cell viability as a percentage: (Abssample - Absblank) / (Abscontrol - Absblank) * 100%. Compare the dose-response curves for different surface modifications.

The experimental workflow for a comprehensive biocompatibility assessment, from surface creation to in vitro and in vivo evaluation, is summarized below.

Assessing the Risk: Advanced Methodologies for Nanotoxicity Evaluation

In the field of nanotoxicology, particularly in the comparative analysis of inorganic versus organic nanoparticles, robust in vitro assessment models are indispensable for early safety screening. These models provide critical insights into biological interactions while offering advantages of reduced cost, time, and ethical concerns compared to in vivo studies. The reliability of drug development and nanomaterial safety assessment heavily depends on accurate prediction of toxicological endpoints, including effects on cellular proliferation, programmed cell death (apoptosis), oxidative stress balance, and genetic integrity (genotoxicity) [30]. Current challenges in the field include bridging the significant gap between simplified in vitro systems and complex clinical outcomes, which often contributes to drug approval failures [30]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various in vitro assessment methodologies, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to enhance their toxicology screening strategies for nanoparticle safety profiling.

Comparative Performance of In Vitro Assays

Key Assay Types and Their Applications

The following table summarizes the primary assay categories used in nanoparticle toxicity assessment, their measurement principles, and key advantages and limitations.

Table 1: Overview of Major In Vitro Toxicity Assessment Assays

| Assay Category | Toxicity Endpoint | Measurement Principle | Key Advantages | Common Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation Assays | Cell viability, growth rate, metabolic activity | Measures metabolic markers (MTT, XTT, WST), ATP content, or DNA synthesis | High-throughput capability, quantitative, cost-effective | May not distinguish between cytostasis and cytotoxicity; can be influenced by nanoparticle interference |

| Apoptosis Assays | Programmed cell death | Detects phosphatidylserine externalization (Annexin V), caspase activation, DNA fragmentation | Distinguishes apoptosis from necrosis, provides mechanistic insight | Requires multiple assays to confirm apoptotic pathway; early-stage detection challenging |

| Oxidative Stress Assays | Reactive oxygen species (ROS), antioxidant depletion | Measures ROS (DCFH-DA), antioxidant levels (GSH), lipid peroxidation (MDA) | Early indicator of toxicity, mechanistic relevance | ROS signals can be transient; assay can be confounded by auto-oxidation |

| Genotoxicity Assays | DNA damage, mutations, chromosomal aberrations | Detects DNA strand breaks (Comet), chromosomal damage (Micronucleus), mutation induction (Ames) | Direct measurement of genetic damage, high predictive value for carcinogenicity | Some assays require dividing cells; may need multiple tests for comprehensive assessment |

Quantitative Performance Metrics for Assay Selection

Selecting appropriate assays requires understanding key performance metrics that indicate reliability and suitability for screening. The following table outlines critical parameters for assay validation and comparison.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for In Vitro Toxicity Assays

| Performance Metric | Definition | Interpretation | Optimal Range for Screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| EC50/IC50 | Concentration producing half-maximal effect/response | Lower values indicate greater potency of a toxic compound | Compound-dependent; used for ranking toxicity potency [31] |

| Signal-to-Background (S/B) | Ratio of test compound signal to untreated control signal | Higher ratios indicate stronger assay response and robustness | High S/B desirable; specific thresholds vary by assay type [31] |

| Z'-Factor (Z') | Statistical parameter assessing assay quality and robustness | Incorporates both signal dynamic range and data variation | 0.5-1.0: Excellent to ideal; <0.5: Poor quality, unsuitable for screening [31] |

| Toxicity Separation Index (TSI) | Measures how well a test differentiates toxic from non-toxic compounds | Continuous number where 1.0 indicates perfect separation | >0.5 indicates predictive capability; closer to 1.0 is superior [32] |

| Toxicity Estimation Index (TEI) | Indicates how well toxic blood concentrations are estimated by in vitro alerts | Higher values indicate better in vitro-in vivo correlation | Improved by using lower effect concentrations (e.g., EC10) and combining endpoints [32] |

Advanced assay systems like the ToxTracker platform exemplify the integration of multiple endpoints, employing six GFP reporter cell lines to discriminate between different types of biological reactivity including DNA damage, oxidative stress, unfolded protein response, and p53-dependent stress [33]. This approach demonstrates outstanding sensitivity and specificity in validation studies using the ECVAM-recommended compound library [33].

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Integrated Oxidative Stress and Genotoxicity Assessment

Principle: This protocol simultaneously evaluates reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and genotoxic potential of nanoparticles in mammalian cells, providing correlated endpoints for mechanistic toxicology.

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell line: Mouse embryonic stem (mES) cells or human cell lines (A549, HepG2, SH-SY5Y) depending on target tissue [34] [33]

- Nanoparticles: Test materials (inorganic: e.g., SiO2, Ag, TiO2; organic: e.g., polymeric, lipid-based)

- ROS detection: DCFH-DA dye (10 µM working concentration)

- Lysis buffer: RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors

- Antioxidant enzymes: SOD, CAT, GPx activity assay kits

- DNA damage markers: γH2AX immunofluorescence or Comet assay reagents

- Culture medium: Appropriate complete medium for selected cell line

- Equipment: Microplate reader, fluorescence microscope, flow cytometer

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Exposure:

- Seed cells in 96-well plates (ROS, viability) and chamber slides (genotoxicity) at optimal density (e.g., 1×10⁴ cells/well)

- Incubate for 24 hours to allow attachment

- Prepare nanoparticle suspensions in serum-free medium with sonication to prevent aggregation

- Expose cells to serial nanoparticle concentrations (e.g., 1-200 µg/mL) for 4-24 hours

- Include positive controls: H2O2 (200 µM, 1h) for ROS, etoposide (25 µM, 24h) for genotoxicity

ROS Measurement:

- After exposure, wash cells with PBS

- Load with DCFH-DA (10 µM) in serum-free medium

- Incubate 30 minutes at 37°C in dark

- Wash with PBS and measure fluorescence (Ex/Em: 485/535 nm)

- Calculate fold increase relative to untreated control

Antioxidant Response Analysis:

- Lysate cells after treatment

- Measure antioxidant enzyme activities:

- Superoxide dismutase (SOD) via inhibition of cytochrome C reduction

- Catalase (CAT) via H2O2 decomposition at 240 nm

- Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) via NADPH oxidation at 340 nm

Genotoxicity Assessment:

- For γH2AX foci:

- Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes

- Permeabilize with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes

- Block with 5% BSA for 1 hour

- Incubate with anti-γH2AX primary antibody (1:1000) overnight at 4°C

- Incubate with fluorescent secondary antibody (1:2000) for 1 hour

- Counterstain with DAPI and visualize via fluorescence microscopy

- Count foci per nucleus (>10 foci/nucleus considered positive)

- For Comet assay:

- Embed cells in low-melting-point agarose on slides

- Lyse overnight in high-salt, detergent-based buffer

- Perform electrophoresis under alkaline conditions (pH>13)

- Stain with SYBR Gold and analyze tail moment using image analysis software

- For γH2AX foci:

Data Analysis:

- Determine EC50 values for ROS induction using non-linear regression

- Calculate correlation coefficients between ROS levels and DNA damage markers

- Establish concentration-response relationships for each endpoint

- Compare potency between inorganic and organic nanoparticles using TSI/TEI metrics [32]

Advanced Multiplexed Toxicity Screening (ToxTracker Assay)

Principle: This stem cell-based reporter assay simultaneously monitors activation of multiple specific stress response pathways, providing mechanistic insight into nanoparticle reactivity [33].

Materials and Reagents:

- ToxTracker mouse embryonic stem cell reporter lines: BSCL2-GFP (DNA damage), SRXN1-GFP (oxidative stress), additional reporters for UPR, p53 pathway [33]

- Nanoparticle suspensions in serum-free medium

- BRL-conditioned mES cell medium

- Gelatin-coated tissue culture plates

- Flow cytometry equipment for GFP quantification

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Exposure:

- Maintain ToxTracker reporter mES cells in knockout medium with LIF on feeder layers

- For experiments, seed cells on gelatin-coated plates in BRL-conditioned medium without feeders

- Allow attachment for 24 hours

- Expose cells to nanoparticle suspensions for 24 hours

- Include appropriate controls and reference compounds

GFP Reporter Measurement:

- Harvest cells after exposure using trypsinization

- Resuspend in PBS containing 2% FCS

- Analyze GFP expression using flow cytometry

- Score as positive if GFP intensity exceeds threshold (2-3-fold above background)

Data Interpretation:

- Specific GFP expression patterns indicate different types of cellular damage:

- BSCL2-GFP activation: DNA replication stress and ATR/Chk1 pathway activation

- SRXN1-GFP activation: Oxidative stress and Nrf2 pathway activation

- Additional reporters: Unfolded protein response, p53 pathway activation

- Profile nanoparticles based on their activation of specific stress pathways

- Specific GFP expression patterns indicate different types of cellular damage:

Validation: This assay has demonstrated outstanding sensitivity (96%) and specificity (89%) using the ECVAM-recommended compound library, effectively discriminating between different mechanisms of toxicity [33].

Signaling Pathways in Nanoparticle-Induced Toxicity

The following diagram illustrates key interconnected signaling pathways activated by nanoparticle exposure in mammalian cells, highlighting points of intervention for assay detection.

Figure 1: Key Signaling Pathways in Nanoparticle Toxicity. This diagram illustrates the interconnected cellular signaling pathways activated by nanoparticle exposure, from initial cellular uptake to final toxicity outcomes. The pathways highlight how different assay endpoints detect specific events in the toxicity cascade.

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive Assessment

The following diagram outlines a systematic workflow for conducting a comprehensive in vitro toxicity assessment of nanoparticles, integrating multiple endpoints.

Figure 2: Comprehensive In Vitro Toxicity Assessment Workflow. This workflow outlines the key steps in a systematic approach to evaluating nanoparticle toxicity, from initial characterization through multiple endpoint assessments to integrated data analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions for Toxicity Assessment

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for In Vitro Toxicity Assessment

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Line Models | Mouse embryonic stem (mES) cells, A549 (lung), HepG2 (liver), SH-SY5Y (neural) [34] [33] | Provide biologically relevant systems for toxicity screening | Stem cells offer pathway proficiency; differentiated cells provide tissue-specific responses |

| Viability/Proliferation Assay Kits | MTT, XTT, WST-1, ATP Lite | Quantify metabolic activity and cell number as surrogates for proliferation | Potential NP interference must be controlled; ATP assays often most reliable |

| Apoptosis Detection Kits | Annexin V/PI, Caspase-Glo, TUNEL | Detect programmed cell death via membrane changes and DNA fragmentation | Multiparametric approaches distinguish apoptosis from necrosis |

| Oxidative Stress Probes | DCFH-DA, MitoSOX, DHE, H2DCFDA | Measure reactive oxygen species generation in different compartments | DCFH-DA detects general ROS; MitoSOX specific for mitochondrial superoxide |

| Antioxidant Assays | GSH/GSSG ratio, SOD, CAT, GPx activity kits | Quantify cellular antioxidant defense capacity | GSH depletion often early indicator of oxidative stress |

| Genotoxicity Assays | Comet, Micronucleus, γH2AX, Ames | Detect DNA damage, chromosomal aberrations, mutations | Comet detects strand breaks; γH2AX indicates double-strand breaks |

| Advanced Reporter Systems | ToxTracker assay (6 GFP reporters) [33] | Multiplexed assessment of specific stress pathway activation | Discriminates between mechanisms of toxicity; high predictive value |

Comparative Data on Nanoparticle Toxicity

Physicochemical Properties Influencing Toxicity

The toxicity of nanoparticles, particularly inorganic variants, is heavily influenced by their physicochemical properties, which should be characterized prior to toxicity assessment.

Table 4: Nanoparticle Properties Affecting Toxicological Profiles

| Property | Toxicity Influence | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Size | Smaller nanoparticles typically show higher toxicity due to increased surface area and cellular uptake [35] | 10nm AgNP caused acute toxicity in mice not seen with 60nm or 100nm; 10-30nm AuNP crossed nuclear membrane, 60nm accumulated in spleen [35] |

| Shape | Cellular uptake and toxicity vary significantly with shape [35] | Spherical NPs internalized more than rods; star-shaped AuNP most cytotoxic; needle-shaped silica more toxic than spherical [35] |

| Surface Coating | Can either mitigate or exacerbate toxicity [35] | Silica-coated iron oxide NPs showed reduced alteration of iron homeostasis and oxidative stress compared to non-passivated NPs [35] |

| Aspect Ratio | High aspect ratio associated with fiber-like pathogenicity [35] | Carbon nanotubes with high aspect ratio caused granulomas and protein exudation in rat lungs [35] |

| Crystallinity | Different crystalline structures of same composition show varying toxicity [35] | Needle-shaped HCPT nanoparticles more potent in apoptotic response despite similar cellular uptake as prismatic forms [35] |

Comparison of Inorganic Nanoparticle Toxicity Profiles

Table 5: Comparative Toxicity Profiles of Selected Inorganic Nanoparticles

| Nanoparticle Type | Key Toxicological Mechanisms | Sensitive Cell Types/Assays | Potency Range (Approximate IC50) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silica (SiNP) | ROS generation, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, lysosomal destabilization, mitochondrial dysfunction [36] | Macrophages (inflammation), lung epithelial cells (ROS), neural cells (oxidative stress) [36] | Varies by size/surface: 10-100 μg/mL (cellular viability) [36] |

| Silver (AgNP) | Strong oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA damage, inflammation [35] | BALB/c mice (acute toxicity), various mammalian cell lines (ROS, genotoxicity) | Size-dependent: 10nm much more toxic than 60-100nm [35] |

| Gold (AuNP) | DNA damage (small sizes), organ accumulation varies with size [35] | Fetal osteoblast, osteosarcoma, pancreatic cells (shape-dependent toxicity) | Shape-dependent: star-shaped > rods > spheres [35] |

| Iron Oxide (SPION) | Oxidative stress, time-dependent cytotoxicity, ROS production [37] | Caco-2 intestinal cells, potential for neural toxicity | Varies by coating: ~50-200 μg/mL (cellular viability) [37] |

The emerging field of "nanotoxicomics" integrates advanced omics technologies (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) with traditional toxicology, enabling multilevel analysis of nanoparticle effects and supporting more accurate extrapolation from in vitro to in vivo systems [34]. This approach has identified specific biomarker patterns, including differential expression of genes related to oxidative stress (SOD1), inflammation (IL-6), and DNA damage (TP53), along with corresponding protein and metabolite alterations [34].

When comparing inorganic versus organic nanoparticles, inorganic particles often demonstrate more pronounced toxicity due to their potential for redox activity, metal ion release, and surface reactivity. However, surface functionalization can significantly modulate this toxicity, sometimes converting noxious particles to relatively nontoxic forms [35]. The comprehensive assessment approach outlined in this guide provides researchers with methodologies to systematically evaluate these differences and develop safer nanoparticle designs for biomedical applications.

The expanding application of nanotechnology in biomedicine necessitates a thorough understanding of the potential adverse effects of nanoparticles (NPs) on human health. In vivo toxicity assessment using animal models is a critical component of this evaluation, providing insights into the organ-specific toxicological endpoints that arise from exposure to these materials. This guide systematically compares the toxicity profiles of organic and inorganic nanoparticles, framing the analysis within the broader context of ongoing research into their distinct biological interactions. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis of current data and methodologies provides a foundation for informed material selection and rigorous safety testing. The fundamental differences in the physicochemical properties of these two classes of nanoparticles—such as their biodegradability, chemical composition, and catalytic activity—underpin their divergent behaviors and toxicities in biological systems [4] [38].

Comparative Toxicity Profiles of Organic and Inorganic Nanoparticles

The toxicity of nanoparticles is governed by a complex interplay of their physicochemical characteristics and the biological environment. The table below summarizes the core differences in the properties and toxicological mechanisms of organic and inorganic nanoparticles, which lead to distinct outcomes in vivo.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties and Toxicity Mechanisms of Organic vs. Inorganic Nanoparticles

| Characteristic | Organic Nanoparticles | Inorganic Nanoparticles |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | Lipids, polymers, carbohydrates [4] | Metals (e.g., Ag, Au), metal oxides (e.g., TiO₂, ZnO, SiO₂) [4] [39] |

| Biodegradability | Typically biodegradable and biocompatible [4] | Often poorly soluble and persistent in biological systems [40] [38] |

| Primary Toxicity Mechanisms | Generally lower inherent cytotoxicity; toxicity often linked to encapsulated drug or immune reactions [4] [40] | Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), oxidative stress, ion release, inflammasome activation [39] [36] [38] |

| Key Influencing Factors | Surface charge, lipid composition, polymer type [4] | Size, shape, crystal structure, surface chemistry, solubility [40] [39] [38] |

| Long-Term Fate | Metabolized and cleared from the body [4] | Potential for long-term accumulation in organs like the liver and spleen [40] |