Optimizing Nanocarrier Distribution at Single-Cell Resolution: Pathways to Precision Therapeutics

This article explores the frontier of controlling nanocarrier distribution with single-cell precision, a critical challenge in targeted drug delivery.

Optimizing Nanocarrier Distribution at Single-Cell Resolution: Pathways to Precision Therapeutics

Abstract

This article explores the frontier of controlling nanocarrier distribution with single-cell precision, a critical challenge in targeted drug delivery. It examines the foundational principles governing nanocarrier design and in vivo journey, highlighting the limitations of conventional biodistribution analysis methods. The content details a groundbreaking methodological pipeline, SCP-Nano, which integrates tissue clearing, light-sheet microscopy, and deep learning to achieve whole-body, single-cell resolution mapping of nanocarriers. It further addresses key troubleshooting and optimization strategies for mitigating off-target effects and enhancing specificity, and concludes with validation frameworks and a comparative analysis of nanocarrier platforms. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource provides a comprehensive roadmap for advancing the development of precise and safe nanocarrier-based therapeutics.

The Foundation of Single-Cell Targeting: Principles and Challenges of Nanocarrier Biodistribution

In single-cell research, achieving precise intracellular delivery is paramount. The journey of a nanocarrier from administration to its intracellular target is predominantly governed by three key physicochemical properties: size, surface charge, and hydrophobicity. These properties act as a master control panel, directly influencing cellular uptake pathways, intracellular trafficking, and ultimately, the therapeutic efficacy of the delivered cargo. A systems-level understanding of these parameters is essential to overcome biological barriers and optimize distribution for single-cell applications [1] [2]. This guide provides troubleshooting resources to help researchers navigate the complex bio-nano interface.

Troubleshooting Guides: Optimizing Key Properties

Troubleshooting Size-Related Issues

The size of a nanocarrier is a critical determinant of its cellular internalization mechanism and rate [3] [4].

Table 1: Size-Related Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Cellular Uptake | Size too small (<50 nm) leading to insufficient phagocytic stimulus [3]. | Increase particle size to the optimal range of 100-200 nm for phagocytic pathways [3] [4]. |

| Rapid Clearance by MPS | Size too large (>200 nm) for intravenous administration, leading to mechanical filtration and high opsonization [3] [4]. | Reduce particle size to below 200 nm and consider surface PEGylation to reduce opsonin adsorption [4]. |

| Poor Target Tissue Penetration | Large size hindering diffusion through tissue extracellular matrix [4]. | Utilize smaller particles (<100 nm) and consider shape engineering (e.g., rod-shaped) for improved penetration [4]. |

| Polydisperse Formulations | Aggregation or inconsistent synthesis methods [5]. | Optimize preparation methods; implement purification techniques like asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation (AF4) [5]. |

Key Experimental Protocol: Measuring Particle Size and Distribution via Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) DLS determines the hydrodynamic diameter of particles based on their Brownian motion in a suspension [5] [6].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the nanocarrier suspension in an appropriate, filtered buffer to obtain a clear, slightly opalescent solution. Ensure the viscosity of the dispersion medium is known [5] [7].

- Instrument Calibration: Use a standard of known size (e.g., latex beads) to calibrate the DLS instrument.

- Measurement: Load the sample into a disposable cuvette and place it in the instrument. Set the measurement temperature (typically 25°C).

- Data Analysis: Perform the measurement in triplicate. The instrument's software will provide the z-average diameter (a intensity-weighted mean size) and the Polydispersity Index (PDI). A PDI value below 0.2 is generally considered monodisperse [5] [7]. For polydisperse samples, a distribution analysis provides a more accurate picture of the subpopulations present.

Troubleshooting Surface Charge (Zeta Potential) Issues

The surface charge, quantified as zeta potential, dictates electrostatic interactions with cell membranes and proteins, affecting stability and uptake [5] [6].

Table 2: Surface Charge-Related Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Aggregation in Storage | Low zeta potential magnitude ( | ζ | < 20 mV) leading to insufficient electrostatic repulsion [5]. | Modify surface chemistry to increase the absolute zeta potential. For cationic particles, ensure | ζ | > +20 mV; for anionic, | ζ | > -20 mV [5]. |

| Non-Specific Cellular Uptake & Toxicity | Highly positive surface charge causing non-specific binding to anionic cell membranes [4] [1]. | Shield the positive charge using PEG or other hydrophilic polymers; aim for a near-neutral or slightly negative charge for reduced non-specific interaction [4]. | ||||||

| Rapid Clearance from Bloodstream | Surface charge promoting opsonin protein adsorption [3] [4]. | Create a stealth surface with neutral, hydrophilic coatings (e.g., PEG) to minimize protein corona formation and phagocytosis [3] [4]. | ||||||

| Inefficient Endosomal Escape | Lack of ionizable cationic lipids that become protonated in the acidic endosomal environment [1]. | Incorporate ionizable lipids with pKa ~6.5 to facilitate the "proton sponge" effect and disrupt the endosomal membrane [1]. |

Key Experimental Protocol: Determining Zeta Potential via Electrophoretic Light Scattering Zeta potential is measured by applying an electric field across the sample and measuring the velocity of particle movement (electrophoretic mobility) using laser Doppler velocimetry [5] [7].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute nanocarriers in a low-concentration salt solution (e.g., 1 mM KCl) or a specific buffer that matches the intended application. The ionic strength and pH of the dispersion medium must be controlled and reported, as they significantly influence the result [5].

- Measurement: Use a disposable folded capillary cell or a dedicated zeta cell. The instrument calculates the zeta potential from the measured electrophoretic mobility.

- Data Analysis: Conduct a minimum of three measurements and report the average value and standard deviation. The accuracy and precision for a suitable sample should be better than 10% on a calibrated instrument [7].

Troubleshooting Hydrophobicity-Related Issues

Hydrophobicity influences protein adsorption, cellular adhesion, and the mechanism of membrane translocation [1] [2].

Table 3: Hydrophobicity-Related Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid Opsonization and Clearance | Hydrophobic surfaces strongly adsorb blood plasma proteins (opsonins) [3] [4]. | Conjugate hydrophilic polymers (e.g., PEG) to create a hydration layer that sterically shields the hydrophobic core [3] [4]. |

| Membrane Embedment without Translocation | Excessively hydrophobic ligands causing nanoparticles to become trapped within the lipid bilayer [1] [2]. | Fine-tune ligand chemistry by incorporating hydrophilic segments (e.g., PEG) or using less hydrophobic alkyl chains to promote full translocation [1] [2]. |

| Poor Loading of Hydrophilic Drugs | Hydrophobic core or matrix incompatible with water-soluble agents. | Switch to nanocarriers with aqueous compartments (e.g., liposomes, nanocapsules) or use surfactants to create nanoemulsions [3]. |

| Low Colloidal Stability in Aqueous Media | High surface hydrophobicity driving aggregation to minimize water contact. | Use stabilizers and surfactants (e.g., polysorbates) during formulation to enhance dispersibility [5]. |

Key Experimental Protocol: Assessing Hydrophobicity via Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC) This method probes surface hydrophobicity based on interaction with a hydrophobic stationary phase.

- Column Selection: Pack a column with a HIC medium (e.g., butyl or phenyl Sepharose).

- Equilibration: Equilibrate the column with a high-salt buffer (e.g., 1.5 M ammonium sulfate) to promote binding.

- Sample Application & Elution: Apply the nanocarrier sample. Elute using a descending salt gradient or with a salt-free buffer. The strength of hydrophobic interaction is inversely related to the salt concentration required for elution.

- Detection: Monitor elution via UV-Vis, fluorescence, or light scattering detectors. More hydrophobic particles will elute at lower salt concentrations.

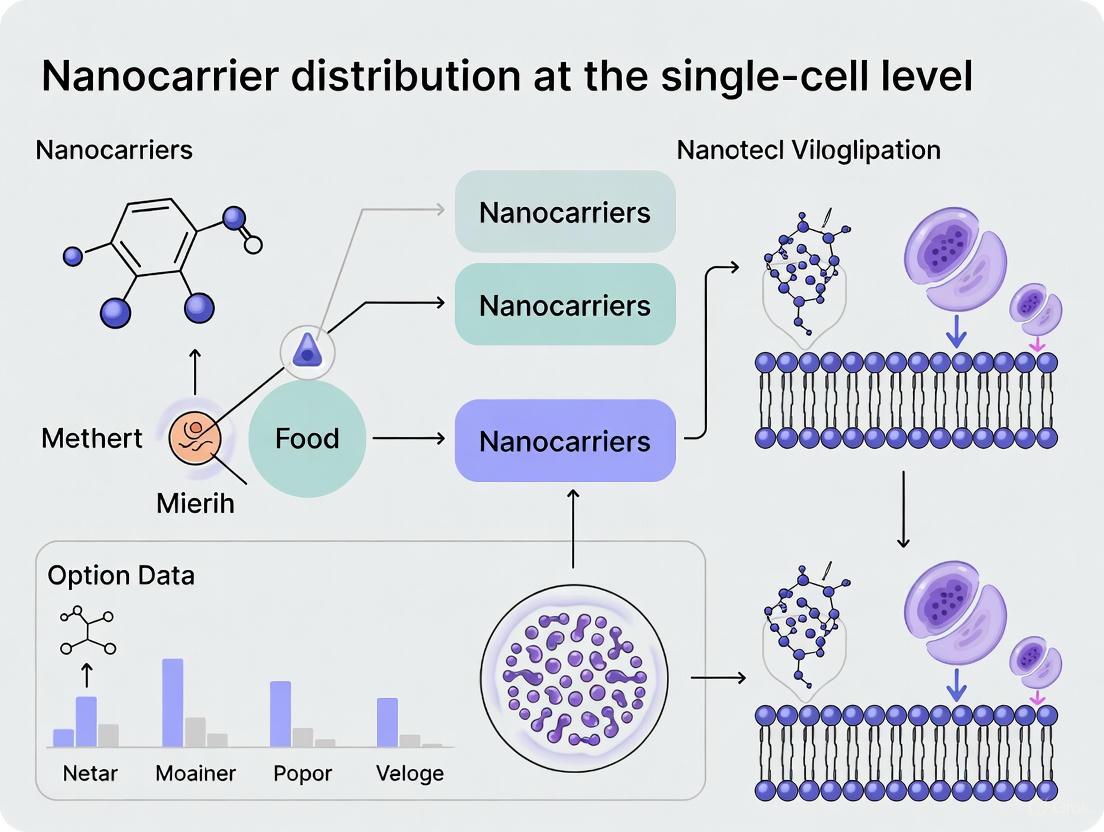

Visualizing the Synergistic Effect on Cellular Entry

The cellular entry pathway is not determined by a single property but by the synergy between size, surface charge, and ligand chemistry (hydrophobicity). Computational studies have identified four primary translocation outcomes, which dictate subsequent intracellular trafficking and fate [1] [2].

Diagram: Synergistic Control of Nanocarrier Entry Pathways. The cellular entry pathway is determined by the interplay of size, surface charge, and ligand hydrophobicity, leading to distinct intracellular fates [1] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents for Nanocarrier Synthesis and Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | Key functional component of LNPs; protonates in acidic endosomes to enable membrane disruption and cytosolic release. | mRNA vaccine delivery (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA) [8]. |

| Phospholipids (e.g., DPPC) | Form the primary bilayer structure of liposomes, providing a biocompatible scaffold. | Model cell membrane studies; creating the main structural matrix of lipid-based nanocarriers [1] [2]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)-Lipids | Shield the surface to reduce protein adsorption (stealth effect), prolong circulation time, and prevent aggregation. | Surface PEGylation of liposomes and LNPs to enhance stability and reduce MPS uptake (e.g., in Doxil) [4] [8]. |

| Cholesterol | Incorporated into lipid bilayers to enhance membrane stability and rigidity, modulating fluidity and permeability. | A standard component in LNP formulations to improve structural integrity and in vivo stability [8]. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument | Measures hydrodynamic particle size distribution and polydispersity index (PDI) in solution. | Routine quality control of nanocarrier size and stability after synthesis [5] [6]. |

| Zeta Potential Analyzer | Determines the surface charge of particles in suspension, predicting colloidal stability. | Assessing the success of surface modifications and the potential for aggregation [5] [7]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Provides high-resolution imaging of nanocarrier morphology, size, and internal structure. | Visualizing the core-shell structure of nanocapsules or the lamellarity of liposomes [5] [6]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My nanocarriers are the right size (~150 nm) but are still not being internalized by my target cell line. What could be wrong? A: Size is only one factor. Check the surface charge. Highly negative surfaces may experience electrostatic repulsion from the anionic cell membrane. Consider modifying the surface with cationic lipids or cell-penetrating peptides to enhance adhesion. Also, verify that your target cells are professional phagocytes if relying on that pathway; many are not [3] [4].

Q2: I am trying to achieve cytosolic delivery for gene editing, but my cargo remains trapped in endosomes. How can I promote endosomal escape? A: This is a common hurdle. Your nanocarriers are likely entering via the "outer wrapping" pathway (endocytosis). To shift towards "free translocation," you need to:

- Incorporate ionizable lipids with a pKa around 6.5. These become protonated in the acidic endosome, leading to membrane destabilization.

- Optimize the synergy: Smaller sizes and higher surface charge/ionization promote pore formation and direct translocation across the membrane, bypassing endosomes [1] [2].

Q3: How does the PEG density on my lipid nanoparticles affect their performance? A: PEG density is a critical balance. While PEG reduces opsonization and extends circulation time, excessive PEGylation can create a steric barrier that inhibits cellular uptake and endosomal escape—a phenomenon known as the "PEG dilemma." Use a minimal amount of PEG-lipid necessary for stability, and consider using cleavable PEG links that shed after the nanocarrier reaches the target site [4] [8].

Q4: My nanoparticle formulation is unstable and aggregates over time. What are the primary factors to check? A: Instability is often linked to surface properties. First, measure the zeta potential. An absolute value below 20-25 mV indicates insufficient electrostatic repulsion to prevent aggregation. Second, assess the surface hydrophobicity, as hydrophobic patches can drive aggregation. Solutions include increasing surface charge via formulation or adding steric stabilizers like PEG [5] [6].

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why can't I detect my nanocarriers in low-dose applications, like vaccines, using conventional imaging? Conventional whole-body imaging techniques, such as bioluminescence imaging, lack the sensitivity for very low doses. Their signal contrast drops drastically at the low doses (e.g., 0.0005 mg kg−1) typical of therapeutic vaccines, making cellular-level detection impossible [9].

FAQ 2: My nanocarriers show good in vitro performance but poor in vivo efficacy. What could be happening? This is often due to unforeseen nano-bio interactions and off-target accumulation. Upon injection, nanocarriers encounter biological barriers and can accumulate in non-target tissues. For example, intramuscularly injected lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have been found to reach heart tissue, leading to local proteome changes [9]. Comprehensive biodistribution analysis at the single-cell level is needed to identify these off-target sites.

FAQ 3: How does the protein corona affect my nanocarrier's journey? When nanocarriers enter the in vivo environment, they inevitably acquire a coating of proteins called the "protein corona". This corona can mask targeting moieties, alter the nanocarrier's cellular interactions, and change its intended biodistribution, potentially reducing its targeting specificity and efficacy [9] [5].

FAQ 4: What are the key nanocarrier properties that influence cellular uptake and biodistribution? The size, surface charge (zeta potential), and surface hydrophobicity of your nanocarrier are critical [5]. To avoid rapid clearance and promote target interaction:

- Size: Ideal size is between 10 nm (to avoid renal clearance) and 200 nm (for tumor extravasation) or 500 nm (to avoid MPS uptake) [10].

- Surface Charge: A near-neutral charge (-10 mV to +10 mV) helps avoid opsonization and MPS recognition [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inefficient Cellular Uptake in Target Tissues

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Lack of Active Targeting.

- Solution: Functionalize the nanocarrier surface with targeting moieties (e.g., antibodies, peptides) that specifically bind to receptors highly expressed on your target cells. This moves from passive to active targeting, increasing specificity [10].

- Cause: Suboptimal Physicochemical Properties.

- Solution: Re-formulate nanocarriers to achieve a size below 200 nm and a neutral surface charge to enhance circulation time and tissue penetration [10]. Consult the table below on characterization techniques.

Problem 2: Rapid Clearance from Bloodstream

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Opsonization and Uptake by the Mononuclear Phagocyte System (MPS).

- Solution: Modify the nanocarrier surface with biocompatibility polymers like polyethylene glycol (PEG) in a process called "PEGylation" or use albumin coatings. This creates a "stealth" effect, reducing opsonin binding and MPS recognition [10].

Problem 3: Inconsistent Experimental Results Due to Nanocarrier Heterogeneity

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Poorly controlled nanocarrier synthesis leads to a broad size distribution (high PDI).

- Solution: Implement rigorous physicochemical characterization. Use techniques like Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to monitor batch-to-batch consistency and Asymmetrical Flow Field-Flow Fractionation (AF4) to fractionate polydisperse samples before analysis [5].

Critical Nanocarrier Characterization Data

Table 1: Essential In Vitro Characterization Techniques for Nanocarriers [5]

| Property | Key Techniques | Brief Principle | Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size & PDI | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Measures particle diameter based on Brownian motion | Fast, statistical data; sensitive to impurities, unreliable for polydisperse samples |

| Asymmetrical Flow Field-Flow Fractionation (AF4) | Separates samples by size in a channel prior to detection | Excellent for complex, polydisperse samples; requires method establishment for each nanocarrier type | |

| Surface Charge | Zeta Potential Measurement | Applies current and uses laser Doppler velocimetry to measure particle movement | Predicts colloidal stability; highly sensitive to pH and ionic strength, requires dilution |

| Morphology | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Scans surface with a probe tip for topographic mapping | Provides ultra-high resolution without special sample treatment; slow scanning, requires expertise |

| Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM) | Uses an electron beam for imaging | High-resolution particle sizing and morphology; minimal information on surface chemistry |

Table 2: Advanced In Vivo Biodistribution Analysis Methods [9] [11]

| Method | Resolution | Key Feature | Throughput | Best for Detecting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCP-Nano (DISCO clearing + AI) | Single-cell | Maps entire mouse body in 3D; high sensitivity for very low doses | Medium (whole organism) | Comprehensive off-target identification at cell level |

| Mass Cytometry (CyTOF) | Single-cell | Uses metal-tagged antibodies; minimal signal overlap | High | Quantifying nano-bio interactions in complex cell mixtures |

| Imaging Flow Cytometry | Single-cell | Combines flow cytometry with microscopy | High | Visual confirmation of nanoparticle internalization per cell |

| Conventional Whole-Body Imaging (e.g., CT, MRI) | Organ-level | Non-invasive, live imaging | Low | Low-sensitivity, macroscopic biodistribution |

Experimental Protocols

This integrated pipeline comprehensively quantifies nanocarrier targeting throughout a whole mouse body with single-cell resolution.

Workflow Overview:

Key Steps:

- Nanocarrier Administration: Inject fluorescence-labeled nanocarriers (e.g., LNPs, liposomes, AAVs) via the chosen route (intravenous, intramuscular, etc.).

- Tissue Clearing: Use the optimized DISCO clearing method. Critical Note: The protocol eliminates urea and sodium azide and reduces dichloromethane incubation time to preserve fluorescence signal.

- Imaging: Image the entire cleared mouse body using light-sheet fluorescence microscopy at a resolution of ~1-2 µm (lateral) and ~6 µm (axial).

- AI Quantification: Analyze the large-scale 3D image data using the trained deep learning model (3D U-Net) to detect and quantify tens of millions of targeted cell instances reliably across different tissues.

This method allows for the quantification of nanoparticle associations with specific cell phenotypes in a complex mixture at high speed.

Workflow Overview:

Key Steps:

- Nanocarrier Labeling: Incorporate a stable elemental isotope (e.g., lanthanide metals) into the nanocarrier during synthesis.

- Cell Incubation & Staining: Incubate labeled nanocarriers with a single-cell suspension. Subsequently, stain the cells with a panel of antibodies conjugated to different metal isotopes to define cell phenotypes.

- Data Acquisition: Introduce cells into the mass cytometer (CyTOF), where they are nebulized into single-cell droplets, vaporized, and ionized.

- Data Analysis: Quantify all metal isotopes simultaneously for each cell. Correlate the elemental signal from the nanocarrier with specific cell phenotype markers to determine which cell types are associated with the nanocarriers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Nanocarrier Development and Tracking [9] [5] [10]

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Common Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | Core component of LNPs; enables encapsulation and endosomal escape of nucleic acids (mRNA, siRNA). | MC3 (clinically approved). Critical for LNP-based vaccines and therapies [9]. |

| PEGylated Lipids | Surface modifier used in liposomes and LNPs; provides a "stealth" coating to reduce MPS clearance and increase circulation time [10]. | Doxil formulation. PEGylation is a key strategy to improve pharmacokinetics. |

| Branched Polyethylenimine (PEI) | A cationic polymer used to form polyplexes for nucleic acid delivery; promotes condensation and cellular uptake. | Can be used for DNA/RNA delivery; optimization of molecular weight is needed to balance efficacy and toxicity [9]. |

| Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs) | Viral vectors for gene delivery; offer high transduction efficiency and potential for long-term gene expression. | Various serotypes (e.g., AAV2, Retro-AAV) have different tissue tropism (e.g., adipocytes) [9]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., Alexa Fluor) | Critical for labeling and tracking nanocarriers or their payloads in vitro and in vivo. | Conjugated to payload (mRNA) or lipid component. Must be chosen and handled to preserve signal during clearing [9]. |

| Elemental Tags (Lanthanides) | Metal isotopes used for labeling nanocarriers in mass spectrometry-based detection (e.g., CyTOF). | Provides a non-overlapping, quantitative signal for high-throughput single-cell analysis of uptake [11]. |

| Targeting Ligands | Surface moieties that bind to specific cell-surface receptors to facilitate active targeting. | Antibodies, peptides, or other small molecules. Conjugated to the nanocarrier surface to improve specificity [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the primary sensitivity limitations of whole-body imaging techniques like PET for nanocarrier analysis? Conventional whole-body imaging techniques, such as positron emission tomography (PET), lack the sensitivity to work with the low doses of nanocarriers employed in many applications, such as preventive and therapeutic vaccines. They cannot identify the millions of individual cells targeted by nanocarriers in three dimensions and struggle to detect low-intensity off-target sites at clinically relevant doses [9].

2. How does the resolution of conventional imaging compare to the needs of single-cell nanocarrier research? Techniques like PET, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) lack the resolution to identify individual cells. They provide organ-level data but cannot resolve biodistribution at the cellular level, which is crucial for understanding nano-bio interactions and off-target effects in nanocarrier development [9].

3. What are the key drawbacks of using 2D histology for biodistribution studies? Traditional histology relies on thin, pre-selected two-dimensional tissue sections. While it offers subcellular resolution and high sensitivity, this approach is not suitable for comprehensive whole-animal analysis. It risks missing critical off-target events that occur outside the selected slices and provides an incomplete picture of distribution patterns [9].

4. What is a major challenge related to the inherent heterogeneity of biological systems? A significant challenge facing traditional pathology and 2D analysis is the concern about sample representativeness caused by intrinsic heterogeneity in lesions, particularly in highly heterogeneous tissues like tumors. This can lead to inaccurate tissue sampling and inter-observer variation in diagnosis [12].

5. Are there integrated technologies that overcome these limitations? Yes, emerging technologies are being developed to bridge these gaps. For instance, the SCP-Nano pipeline integrates whole-mouse tissue clearing, light-sheet microscopy, and a dedicated deep-learning analysis to map nanocarrier biodistribution throughout the entire mouse body with single-cell resolution and high sensitivity, overcoming the limitations of both conventional imaging and histology [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Key Experimental Challenges

This guide helps diagnose and resolve common problems encountered when using conventional methods for nanocarrier biodistribution analysis.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Limitations

| Problem | Underlying Cause | Potential Solution | Considerations & Alternative Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inability to detect nanocarriers at low, clinically relevant doses [9] | Limited sensitivity of PET, CT, and optical imaging. | • Increase injection dose (may cause toxicity and not reflect clinical use). • Use more sensitive radioisotopes or brighter fluorescent tags. | Consider switching to high-sensitivity methods like tissue clearing with light-sheet microscopy (e.g., SCP-Nano) that can detect doses as low as 0.0005 mg kg⁻¹ [9]. |

| Missing critical off-target nanocarrier accumulation [9] | reliance on pre-selected 2D histological sections; low contrast in whole-body imaging. | • Increase the number of histological sections analyzed (time-consuming). • Use hybrid imaging (e.g., PET/CT) for better anatomical context [12]. | Implement a whole-body, 3D analysis method like SCP-Nano to comprehensively map all targeted cells without pre-selection bias [9]. |

| Lacking cellular-resolution data from whole-body experiments [9] | inherent resolution limits of PET, CT, and MRI. | • Perform ex vivo histology on dissected organs (destructive and not whole-body). | Adopt a 3D imaging pipeline that maintains single-cell resolution across the entire organism. Correlate low-resolution whole-body images with high-resolution histological data from specific regions [9]. |

| Difficulty quantifying cell-level biodistribution accurately and at scale | reliance on manual counting or simple thresholding in images, which is prone to error and not scalable. | • Use commercial software (e.g., Imaris), though performance may be suboptimal (F1 scores <0.50 reported) [9]. | Implement a robust deep learning-based quantification pipeline trained for your specific nanocarrier and tissue type to reliably detect and quantify tens of millions of targeted cells [9]. |

Experimental Protocol: Single-Cell Precision Nanocarrier Identification (SCP-Nano)

The following workflow outlines the SCP-Nano method, an integrated pipeline designed to overcome the limitations of conventional biodistribution analysis [9].

Objective: To comprehensively map and quantify the biodistribution of fluorescently labeled nanocarriers throughout an entire mouse body at single-cell resolution.

Workflow for High-Resolution Biodistribution Analysis

Materials and Reagents:

- Fluorescently labeled nanocarriers (e.g., LNPs, liposomes, AAVs).

- Mice (appropriate model for your study).

- Fixative (e.g., paraformaldehyde).

- Reagents for optimized DISCO clearing protocol (note: urea and sodium azide are omitted, and dichloromethane incubation time is reduced to preserve fluorescence) [9].

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Methodology:

- Nanocarrier Administration: Inject fluorescently labeled nanocarriers into mice via the desired route (e.g., intravenous, intramuscular) at therapeutically relevant doses [9].

- Tissue Preparation and Clearing:

- At the chosen time point, perfuse mice transcardially with PBS followed by fixative to preserve tissue architecture.

- Dissect out the entire mouse body or organs of interest.

- Subject the samples to the optimized DISCO tissue clearing protocol. Critical steps include the omission of urea and sodium azide and reduced incubation time in dichloromethane to maximize fluorescence preservation throughout the mouse body [9].

- 3D Image Acquisition:

- Image the cleared whole-mouse body using light-sheet fluorescence microscopy.

- Aim for a resolution of approximately 1–2 µm (lateral) and 6 µm (axial) to achieve single-cell resolution across the entire body [9].

- AI-Based Image Analysis:

- Process the large-scale 3D imaging data using the SCP-Nano deep learning pipeline.

- The pipeline uses a 3D U-Net architecture to segment and identify nanocarrier-positive cells reliably.

- This model has been shown to achieve a high average instance F1 score (0.7329), significantly outperforming existing methods [9].

- Data Quantification and Visualization:

- Use the pipeline's output to quantify nanocarrier delivery at the organ, tissue, and single-cell level.

- Generate 3D maps of nanocarrier distribution for comprehensive analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Advanced Single-Cell Biodistribution Studies

| Item | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A leading nanocarrier platform for protecting and delivering macromolecular drugs like mRNA [9]. | Used as the delivery vehicle for SARS-CoV-2 spike mRNA in vaccines; can be loaded with EGFP mRNA for tracking in biodistribution studies [9]. |

| Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs) | Viral vectors with potential for gene therapy; different serotypes exhibit distinct tissue tropism [9]. | Used to transduce specific cell populations (e.g., AAV2 variant Retro-AAV transduces adipocytes) for gene delivery studies [9]. |

| Tissue Clearing Reagents | Chemicals used to render tissues transparent by matching refractive indices of components. | Essential for the DISCO method, enabling deep light penetration for 3D microscopy of whole organs or bodies [9]. |

| Fluorescent Tags (e.g., Alexa Fluor dyes) | Molecules conjugated to nanocarriers or their cargo to enable optical detection. | Tagging mRNA or lipid components of LNPs with Alexa Fluor 647 or 750 allows visualization after tissue clearing and imaging [9]. |

| Deep Learning Models (3D U-Net) | Artificial intelligence models designed for segmenting 3D biological imaging data. | The core of the SCP-Nano pipeline, used to accurately identify and quantify millions of nanocarrier-targeted cells in a high-throughput, unbiased manner [9]. |

The development of precise nanocarriers for drug delivery, gene therapy, and vaccine applications represents a frontier in modern medicine. A significant obstacle in this field is the "single-cell targeting gap"—the critical inability of conventional technologies to comprehensively analyze nanocarrier biodistribution at the resolution of individual cells across entire living organisms. This gap hinders the rational design of next-generation nanocarriers that maximize therapeutic efficacy for target tissues while minimizing off-target effects [9] [11].

Existing methods for analyzing nanocarrier biodistribution, such as positron emission tomography (PET), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), lack the resolution to identify the millions of individual cells targeted by nanocarriers in three dimensions. These techniques also often lack the sensitivity to work with the low doses employed in applications like preventive and therapeutic vaccines [9]. Conversely, traditional histological approaches offer subcellular resolution and high sensitivity but rely on thin, pre-selected two-dimensional tissue sections, making them unsuitable for whole-animal analysis [9]. This technological limitation creates a critical knowledge gap in understanding the true distribution, efficacy, and potential toxicity of nanomedicines.

Key Technologies Bridging the Resolution Gap

SCP-Nano: Whole-Body Single-Cell Mapping

The Single Cell Precision Nanocarrier Identification (SCP-Nano) pipeline represents an integrated experimental and deep learning approach to comprehensively quantify the targeting of nanocarriers throughout the whole mouse body at single-cell resolution [9] [13]. This method enables the visualization and quantification of nanocarrier distribution with unprecedented sensitivity, working at doses as low as 0.0005 mg kg⁻¹—far below the detection limits of conventional whole-body imaging techniques [9].

Experimental Workflow of SCP-Nano:

Diagram 1: SCP-Nano whole-body mapping workflow.

wildDISCO: Whole-Body Immunostaining

The wildDISCO method uses standard antibodies with fluorescent markers to create detailed 3D maps of entire mouse bodies, providing unprecedented visualization of biological systems. This technique involves perfusing antibodies throughout the vasculature of a non-living animal, followed by optical clearing and light-sheet fluorescence microscopy [14]. The resulting data provides body-wide maps of specific molecules, structures, or cells of interest, creating valuable contextual information for understanding nanocarrier distribution within intact biological systems.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key research reagents and materials for high-resolution nanocarrier mapping

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Protect and deliver RNA therapeutics; clinically approved delivery system | mRNA vaccine delivery; study biodistribution after different injection routes [9] |

| Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs) | Highly efficient gene delivery vectors; different serotypes have distinct tissue tropisms | Gene therapy; mapping transduction patterns across tissues [9] [13] |

| DNA Origami Structures | Programmable nanoscale structures with precise control over shape and function | Customized drug delivery; study of design principles affecting biodistribution [9] [13] |

| Optical Tissue Clearing Reagents | Render tissues transparent while preserving fluorescence | Enabling deep-tissue imaging for whole-organism analysis (DISCO method) [9] [14] |

| Fluorescently-Labeled Antibodies | Target-specific markers for structural and cellular identification | wildDISCO: mapping nervous system, lymphatic vessels, and immune cells [14] |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the minimum dose of nanocarriers that SCP-Nano can detect, and why is this significant?

SCP-Nano can detect nanocarriers at doses as low as 0.0005 mg kg⁻¹, which is approximately 100-1,000 times lower than the detection limits of conventional imaging techniques like bioluminescence imaging [9]. This is particularly significant for vaccine development, where such low doses are typically used, and conventional methods fail to provide adequate contrast or resolution.

Q2: How does SCP-Nano handle the enormous data generated from whole-body imaging?

SCP-Nano employs a robust deep learning pipeline based on a 3D U-Net architecture with six encoding and five decoding layers. This AI approach partitions whole-body imaging data into discrete units for analysis within typical memory constraints, achieving an average instance F1 score of 0.7329 for segmenting targeted cells across diverse tissues [9].

Q3: Can these methods identify unexpected nanocarrier accumulation in off-target tissues?

Yes. For example, SCP-Nano revealed that intramuscularly injected LNPs carrying SARS-CoV-2 spike mRNA can reach heart tissue, leading to proteome changes that suggest immune activation and blood vessel damage [9]. This capability allows researchers to identify potentially problematic off-target accumulation before clinical trials.

Q4: What types of nanocarriers can be analyzed with these high-resolution methods?

The technology generalizes to various nanocarriers, including lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), liposomes, polyplexes, DNA origami, and adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) [9]. For instance, SCP-Nano revealed that an AAV2 variant transduces adipocytes throughout the body, information crucial for designing targeted gene therapies.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Table 2: Troubleshooting guide for high-resolution nanocarrier mapping experiments

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor fluorescence signal after tissue clearing | Signal loss due to harsh clearing reagents | Optimize DISCO protocol: eliminate urea and sodium azide; reduce dichloromethane incubation time | [9] |

| Suboptimal cell segmentation in AI analysis | Inadequate training data or model architecture | Use virtual reality-based annotation for training; employ 3D U-Net with leaky ReLU activation | [9] |

| Inconsistent antibody penetration in whole-body staining | Large antibody size preventing homogeneous distribution | Use membrane permeability enhancers to facilitate deep, even penetration without aggregation | [14] |

| Difficulty correlating distribution with biological effects | Lack of spatial proteomic data integration | Combine SCP-Nano with spatial proteomics to reveal molecular changes in target tissues | [9] |

| Low annotation accuracy for rare cell types | Imbalanced cell-type distributions in data | Use methods with high macro F1 scores (like STAMapper) that proficiently identify rare cell types | [15] |

Advanced Computational Methods for Spatial Mapping

STAMapper for Cell-Type Annotation

For spatial transcriptomics data, STAMapper provides a heterogeneous graph neural network to accurately transfer cell-type labels from single-cell RNA-sequencing data to single-cell spatial transcriptomics data. This method demonstrates significantly higher accuracy compared to competing methods (scANVI, RCTD, and Tangram), particularly for datasets with fewer than 200 genes [15]. The method constructs a heterogeneous graph where cells and genes are modeled as distinct node types connected based on expression patterns.

Computational Architecture of STAMapper:

Diagram 2: STAMapper computational workflow for cell-type annotation.

CMAP for Spatial Cell Mapping

Cellular Mapping of Attributes with Position (CMAP) is another algorithm designed to precisely predict single-cell locations by integrating spatial and single-cell transcriptome datasets. This approach enables the reconstruction of genome-wide spatial gene expression profiles at single-cell resolution through a three-level mapping process: DomainDivision, OptimalSpot, and PreciseLocation [16]. CMAP has demonstrated a 99% cell usage ratio and successfully mapped 2,215 out of 2,242 cells in benchmark tests, significantly outperforming other methods like CellTrek and CytoSPACE [16].

Future Directions and Implementation Considerations

The integration of high-resolution imaging, tissue clearing, and artificial intelligence represents a paradigm shift in nanocarrier research. These technologies enable researchers to address previously intractable questions about nanocarrier behavior at the single-cell level throughout entire organisms. The future of this field will likely involve:

- Increased multiplexing: Simultaneous use of numerous antibodies or markers to model multiple complex systems together [14].

- Enhanced AI integration: Using high-quality, large-scale imaging data to train deep learning algorithms that can predict disease progression and treatment efficacy without additional animal experiments [14].

- Broader accessibility: Development of user-friendly tools that democratize advanced analysis, such as DELiVR for brain cell mapping, which eliminates the need for coding expertise [14].

For research groups seeking to implement these technologies, establishing local core facilities with specialized instruments—including microfluidic devices for library preparation, fluorescent microscopes, flow cytometers, and computational hardware—is essential. Additionally, investment in training for single-cell laboratory techniques, data analysis, and sustainable funding is critical for building institutional capacity in this transformative field [17].

SCP-Nano: A Breakthrough Pipeline for Whole-Body, Single-Cell Nanocarrier Imaging and AI Quantification

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is SCP-Nano and what is its primary function? SCP-Nano (Single Cell Precision Nanocarrier Identification) is an integrated experimental and deep learning pipeline designed to comprehensively quantify the targeting of nanocarriers throughout an entire mouse body at single-cell resolution. It combines optical tissue clearing, light-sheet microscopy, and deep-learning algorithms to map and quantify nanocarrier biodistribution with high sensitivity. [9] [13]

What types of nanocarriers can be analyzed using SCP-Nano? The platform generalizes to various types of nanocarriers, including Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), liposomes, polyplexes, DNA origami structures, and adeno-associated viruses (AAVs). [9] [13]

What is the key advantage of SCP-Nano over conventional imaging techniques? SCP-Nano can detect nanocarriers at doses as low as 0.0005 mg kg−1, which is far below the detection limits of conventional whole-body imaging techniques like bioluminescence, PET, CT, or MRI. It also provides single-cell resolution across the entire organism, unlike traditional methods. [9] [18]

What was a significant finding made possible by SCP-Nano? Using SCP-Nano, researchers demonstrated that intramuscularly injected LNPs carrying SARS-CoV-2 spike mRNA can reach heart tissue. Subsequent proteomic analysis of the heart revealed changes in protein composition, suggesting immune activation and possible blood vessel damage. [9] [13] [19]

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue 1: Poor Fluorescence Signal After Tissue Clearing

- Potential Cause: Signal degradation from harsh clearing chemicals.

- Solution: Use the optimized DISCO clearing protocol. Eliminate urea and sodium azide from the process and reduce dichloromethane (DCM) incubation time to better preserve the fluorescence signal of tagged mRNAs. [9]

Issue 2: Suboptimal AI-Based Cell Segmentation

- Potential Cause: Use of generic segmentation tools not tailored for this specific data.

- Solution: Implement the dedicated SCP-Nano deep learning pipeline. The provided 3D U-Net architecture, trained on manually annotated 3D patches from diverse tissues, significantly outperforms existing methods like Imaris or DeepMACT, achieving an average instance F1 score of 0.73. [9]

Issue 3: Inconsistent Biodistribution Results

- Potential Cause: Variability in injection routes affecting LNP tropism.

- Solution: Strictly control and document the administration route (e.g., intravenous, intramuscular, intranasal). SCP-Nano has revealed that distribution patterns are highly dependent on the injection route. [9]

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Whole-Mouse Body Processing and Imaging for SCP-Nano

This protocol describes the steps for preparing and imaging a whole mouse body to visualize nanocarrier distribution at single-cell resolution. [9]

- Nanocarrier Administration: Inject fluorescence-labeled nanocarriers into the mouse model (e.g., via intramuscular or intravenous route) at the desired dose.

- Perfusion and Fixation: Perfuse the mouse with a fixative solution (e.g., paraformaldehyde) to preserve tissue structure.

- Optimized Tissue Clearing: Process the entire mouse body using the refined DISCO clearing method. Key modifications include:

- Omitting urea and sodium azide from clearing solutions.

- Reducing the incubation time in dichloromethane (DCM).

- Light-Sheet Microscopy: Image the transparent whole mouse body using a light-sheet microscope. The achieved resolution is approximately 1–2 µm (lateral) and approximately 6 µm (axial), enabling single-cell resolution across the entire body.

Protocol 2: AI-Based Quantification of Targeted Cells

This protocol outlines the process for analyzing the large-scale imaging data to detect and quantify nanocarrier-targeted cells. [9]

- Data Partitioning: Partition the whole-body imaging data into smaller, manageable 3D patches to fit computational memory constraints.

- Deep Learning Segmentation: Analyze the patches using the trained 3D U-Net model. This architecture features six encoding and five decoding layers with a leaky ReLU activation function.

- Instance Identification and Quantification: Use the

cc3dlibrary to identify each segmented cell or cluster instance. Calculate the size and intensity contrast of each instance relative to its local background. - Data Aggregation and Visualization: Compute organ-level statistics and create 3D maps of nanocarrier density within organs or volumes of interest.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Materials and Reagents for SCP-Nano Experiments

| Item Name | Type/Model | Primary Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | MC3-based (clinical grade) | Model nanocarrier for delivering mRNA therapeutics. [9] |

| Fluorescent Tags | Alexa Fluor 647, Alexa 750 | Tagging mRNA or lipid components to enable optical detection. [9] |

| DISCO Clearing Reagents | Custom formulation | Renders entire mouse bodies transparent for deep-tissue imaging. [9] |

| Light-Sheet Microscope | Not Specified | Generates high-resolution 3D images of cleared tissues. [9] [13] |

| Deep Learning Model | 3D U-Net Architecture | Detects and quantifies nanocarrier-targeted cells from 3D image data. [9] |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathway Visualizations

SCP-Nano Whole-Process Workflow

LNP-Induced Cardiac Proteome Changes

Optimized Tissue Clearing and Light-Sheet Microscopy for Sensitive 3D Imaging

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Signal Loss During Tissue Clearing

Problem: Diminished fluorescence signal after the tissue clearing process, jeopardizing data quality.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorophore Instability | Verify specific dye used (e.g., Alexa Fluor 647). Test clearing protocol on a control slice. | Optimize the DISCO protocol by eliminating urea and sodium azide and reducing dichloromethane (DCM) incubation time [9]. |

| Incomplete Clearing | Sample appears opaque or cloudy. High background noise in images. | For aqueous methods, ensure adequate incubation time (can take weeks for large samples). For solvent-based methods, confirm proper dehydration steps prior to clearing [20]. |

| Sample Over-Clearing | Sample becomes fragile; cellular structures may degrade. | Standardize and strictly adhere to incubation times. For delicate samples, consider milder hyperhydrating methods like ScaleS [20]. |

Light-Sheet Microscopy Imaging Artifacts

Problem: Images exhibit stripes, shadows, or uneven illumination.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Light-Sheet Striping | Observe static, repeating dark and bright lines in the image along the illumination axis. | Utilize a microscope system with built-in destriping via light-sheet pivoting. An ultrafast scanning mirror can create a homogeneous illumination profile [21]. |

| Sample-Induced Scattering | Artifacts worsen in deeper tissue regions. | Employ multi-view imaging (e.g., with a Luxendo MuVi SPIM). Rotate the sample, acquire images from different angles, and fuse them computationally [21]. |

| Poor Sheet Alignment | Signal and resolution are optimal only in a thin plane. | Follow manufacturer's alignment protocol. Use fluorescent beads embedded in agarose to visually align the light-sheet with the focal plane of the detection objective. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Workflow

Q1: Why should I use tissue clearing for nanocarrier biodistribution studies instead of conventional histology? Traditional histology relies on thin 2D sections, making it unsuitable for comprehensive 3D mapping of nanocarriers throughout entire organs or organisms. Tissue clearing, coupled with light-sheet microscopy, allows for the visualization and quantification of nanocarrier delivery at single-cell resolution across vast tissue volumes, revealing off-target sites that 2D sections can easily miss [9] [20].

Q2: My research involves both live cell imaging and cleared tissues. Do I need two different microscopes? No. Certain light-sheet systems, like the Luxendo MuVi SPIM, are designed for this purpose. A simple exchange of the central optical unit (e.g., the octagon) allows you to switch between imaging live samples (e.g., organoids) and large, cleared samples (e.g., whole organs) on the same instrument within minutes [21].

Technical Optimization

Q3: How can I improve the axial resolution of my light-sheet images? Axial resolution can be improved by implementing a multi-view imaging approach. By imaging the sample from different angles and applying subsequent image processing steps—including registration, fusion, and deconvolution—you can create an isotropic dataset with nearly equal resolution in the X, Y, and Z dimensions [21].

Q4: What is the major advantage of light-sheet microscopy over confocal microscopy for large samples? The primary advantages are significantly reduced phototoxicity and photobleaching, along with much faster 3D image acquisition. Light-sheet microscopy illuminates only the thin plane being imaged, whereas confocal microscopy illuminates the entire sample volume, generating out-of-focus light that is then rejected by a pinhole. This makes light-sheet microscopy far superior for long-term live imaging and for managing the large datasets from cleared tissues [21].

Q5: Can I perform long-term live imaging with light-sheet microscopy? Yes. Systems equipped with environmental control modules can precisely manage temperature (e.g., 20°C to 39°C), CO₂ (0%-15%), O₂ (1%-21%), and humidity (20%-99%) for continuous acquisitions lasting up to several days [21].

Experimental Protocols

Optimized DISCO Tissue Clearing for Fluorescent Nanocarriers

This protocol is optimized for preserving the fluorescence of tagged mRNAs and lipids in nanocarriers like LNPs during whole-body clearing [9].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Dehydration Solutions: Methanol in distilled water (20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, 100%, v/v).

- Delipidation/Decolorization Solution: Dichloromethane (DCM). (Note: Incubation time must be optimized and minimized to preserve fluorescence).

- Refractive Index Matching Solution: DiBenzyl Ether (DBE).

Detailed Workflow:

- Perfusion and Fixation: Perfuse the mouse transcardially with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Dissect out organs or use the whole body and post-fix by immersion in 4% PFA at 4°C for 24 hours.

- Dehydration: Immerse the sample in a graded series of methanol in water (20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, 100%, 100%) at 4°C. Incubate for 1 hour per step.

- Decolorization and Delipidation: Incubate the sample in 100% dichloromethane (DCM) at room temperature. Critical Step: The original DISCO protocol is modified here by reducing the DCM incubation time (e.g., to 2-3 hours) to prevent fluorescence quenching [9].

- Refractive Index Matching: Transfer the sample to DiBenzyl Ether (DBE) for storage and imaging. The sample should become transparent within hours.

- Mounting for Microscopy: Mount the cleared sample in a custom-made chamber or quartz cuvette filled with DBE for imaging with an inverted light-sheet microscope [21].

SCP-Nano AI-Based Quantification Workflow

This protocol details the steps for quantifying nanocarrier-targeted cells from large light-sheet imaging datasets [9].

Workflow Overview:

Key Steps:

- Data Preparation: Partition the terabyte-sized whole-body imaging data into smaller, discrete 3D patches (e.g., 200x200x200 to 300x300x300 voxels) for processing within standard GPU memory constraints [9].

- Annotation for Training: Create a ground-truth training dataset using a Virtual Reality (VR)-based annotation tool, which has been shown to be superior to 2D screen-based annotation for 3D data. Annotate patches from diverse tissues (spleen, liver, lymph nodes, etc.) [9].

- Model Training: Train a 3D U-Net architecture with six encoding and five decoding layers, using a leaky ReLU activation function. Use five-fold cross-validation to monitor performance and avoid overfitting. The benchmark for success is an average instance F1 score of >0.73 on an independent test dataset [9].

- Prediction and Analysis: Apply the trained model to new whole-body data. Use the

cc3dlibrary to identify each segmented cell or cluster instance and compute statistics like size and intensity contrast relative to the background for organ-level quantification [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Description | Application Example in Nanocarrier Research |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Clinically approved nanocarriers (e.g., based on MC3 lipid) for protecting and delivering macromolecular drugs like mRNA [9]. | Delivery of SARS-CoV-2 spike mRNA; studying route-dependent biodistribution (intramuscular vs. intravenous) [9]. |

| Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs) | Viral vector nanocarriers for efficient gene delivery. Different serotypes (e.g., AAV2 variant Retro-AAV) have distinct tissue tropisms [9]. | Identifying off-target tissue transduction, such as adipocyte targeting by an AAV2 variant [9]. |

| DNA Origami | Programmable nanocarriers offering ease of production and modification [9]. | Studying the biodistribution of a novel, highly customizable nanocarrier platform [9]. |

| Optimized DISCO Solutions | A solvent-based clearing protocol modified by eliminating urea and reducing DCM time to preserve fluorescence [9]. | Enabling sensitive 3D imaging of LNP distribution at single-cell resolution across entire mouse bodies [9]. |

| DiBenzyl Ether (DBE) | A high-refractive index (∼1.55) organic solvent used as the final immersion medium in DISCO and uDISCO clearing [9] [20]. | Rendering dehydrated and delipidated samples transparent for light-sheet microscopy. |

| High RI Aqueous Solutions | Solutions like RapiClear or SeeDB2 that match tissue RI without harsh solvents, preserving lipids [20]. | Clearing smaller samples (e.g., organoids, tissue slabs) when lipid staining is required. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common causes of shape mismatch errors in 3D U-Net implementations, and how can I resolve them?

Shape mismatch errors frequently occur when the input dimensions are not divisible by 2^N, where N is the number of downsampling layers in the network [22]. In a standard U-Net with 5 downsampling layers, your input dimensions must be divisible by 32 (2^5). For example, an input size of 376×128 will cause concatenation errors because 376 is not divisible by 32 [22].

Solutions:

- Input Resizing/Cropping: Resize or crop your input volumes to compatible dimensions (e.g., 384×128).

- Architecture Modification: Use custom padding in convolutional layers or adjust the number of downsampling operations.

- Layer Verification: Ensure decoder layers precisely match corresponding encoder layers in spatial dimensions before concatenation.

Q2: My 3D U-Net produces poor segmentation on crowded cells or complex morphologies. How can I improve accuracy?

Traditional 3D U-Net architectures often struggle with crowded cells and complex biological structures [23] [24]. The u-Segment3D framework addresses this by leveraging superior 2D segmentation models from multiple orthogonal views to generate a consensus 3D segmentation, often outperforming native 3D approaches for complex morphologies [23].

Implementation Strategy:

- Utilize u-Segment3D: Apply established 2D segmentation models (Cellpose, μSAM) on orthogonal views [23]

- Optimize Architecture: For native 3D U-Nets, increase network width for tasks with numerous segmentation classes, as wider networks show significant benefits for high label complexity (>10 classes) [25]

- Leverage Alternative Algorithms: Consider algorithms like CellSNAP for specific imaging modalities like quantitative phase imaging (QPI), which excels with clumped cells and complex morphologies [24]

Computational requirements vary significantly based on architecture choices [25]. The "bigger is better" approach often yields minimal gains with substantial computational costs.

Resource Optimization Guidelines:

- Memory Efficiency: For high-resolution images (voxel spacing <0.8mm), prioritize increasing resolution stages to expand receptive field [25]

- Parameter Efficiency: For anatomically regular structures (high sphericity >0.6), deeper networks provide significant benefits; for intricate shapes, depth offers diminishing returns [25]

- Architecture Selection: Consider automated approaches like GA-UNet, which achieves competitive performance with merely 0.24%-0.67% of original U-Net parameters [26]

Q4: How can I adapt 3D U-Nets for specialized applications like nanocarrier tracking at single-cell resolution?

The SCP-Nano pipeline demonstrates an integrated approach combining tissue clearing, light-sheet microscopy, and deep learning for single-cell resolution tracking throughout entire organisms [9] [13].

Key Adaptation Strategies:

- Pipeline Integration: Combine tissue clearing methods (e.g., optimized DISCO protocol) with 3D U-Net segmentation

- Sensitivity Optimization: Implement detection algorithms that don't rely on single-value thresholding but make predictions based on contextual patterns [9]

- Validation: Correlate with histological sections to confirm signal preservation after tissue clearing [9]

Troubleshooting Guides

Input Shape and Dimension Issues

Table: Common 3D U-Net Shape Errors and Solutions

| Error Type | Example Error Message | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concatenation Dimension Mismatch | ValueError: A Concatenate layer requires inputs with matching shapes except for the concatenation axis. Received: input_shape=[(None, 46, 16, 512), (None, 47, 16, 512)] [22] |

Input dimensions not divisible by 2^N where N is downsampling steps | Adjust input dimensions to be divisible by 2^N or use custom padding |

| Padding Incompatibility | ValueError: CudaNdarray_CopyFromCudaNdarray: need same dimensions for dim 1, destination=13, source=14 [27] |

Potential bugs with padding='same' in 3D layers |

Use padding='valid' with manual dimension calculation or explicit input padding |

| Skip Connection Mismatch | Dimension errors during decoder-encoder concatenation | Inconsistent cropping or resizing between encoder and decoder paths | Implement identical cropping or use reflection padding |

Performance and Optimization Problems

Table: 3D U-Net Performance Optimization Strategies

| Performance Issue | Diagnosis Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low segmentation accuracy on crowded cells | Evaluate cell density and morphology complexity | Implement u-Segment3D consensus approach [23] or CellSNAP algorithm [24] |

| Slow inference time | Measure inference speed vs. model size | Use smaller architectures (e.g., S4D3W16) which often perform competitively with larger models [25] |

| Poor generalization to new cell types | Analyze training data diversity | Incorporate data augmentation or leverage foundation models (Cellpose, μSAM) [23] |

| High memory consumption | Monitor GPU memory during training | Reduce batch size, use mixed-precision training, or implement gradient checkpointing |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: SCP-Nano Pipeline for Nanocarrier Distribution Analysis

Application: Single-cell resolution tracking of nanocarriers throughout entire organisms [9] [13]

Materials:

- Fluorescence-labeled nanocarriers (LNPs, liposomes, polyplexes, DNA origami, AAVs)

- Mouse model

- Optimized DISCO tissue clearing reagents (urea-free, reduced DCM incubation)

- Light-sheet microscope

- High-performance computing resources with GPU

Methodology:

- Administration: Inject fluorescence-labeled nanocarriers (doses as low as 0.0005 mg kg−1) via chosen route (intramuscular, intravenous, intranasal)

- Tissue Processing: Apply optimized DISCO clearing protocol (eliminate urea and sodium azide, reduce DCM incubation) to preserve fluorescence [9]

- Imaging: Acquire whole-body images at ~1-2μm lateral and ~6μm axial resolution using light-sheet microscopy

- AI Analysis: Process data through SCP-Nano 3D U-Net pipeline:

- Partition whole-body data into manageable units

- Apply trained 3D U-Net with six encoding/five decoding layers (leaky ReLU activation)

- Identify targeted cells/clusters using cc3d library

- Calculate organ-level statistics and nanocarrier density

Validation: Correlate with histological sections pre- and post-clearing to confirm signal preservation [9]

Protocol 2: u-Segment3D for Complex Cell Morphologies

Application: 3D segmentation of crowded cells or complex structures using 2D segmentation models [23]

Materials:

- 3D image volume (any modality: cell aggregates, tissue, embryos, vasculature)

- Pre-trained 2D segmentation model (Cellpose, μSAM, CellSAM, or transformer models)

- u-Segment3D toolbox (Python package)

Methodology:

- 2D Segmentation: Apply 2D instance segmentation to all orthogonal views (x-y, x-z, y-z slices)

- Consensus Generation: Input 2D segmentations to u-Segment3D framework:

- Framework reconstructs 3D gradient vectors of distance transform representation

- Performs gradient descent and spatial connected component analysis

- Generates consensus 3D instance segmentation

- Validation: Compare with ground truth manual segmentations

Advantages: Eliminates need for extensive 3D training data; leverages superior 2D segmentation performance [23]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for 3D Cell Segmentation and Nanocarrier Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Nanocarrier for drug/gene delivery | MC3-ionizable lipid, PEG coating, fluorescent tagging [9] | mRNA vaccine delivery, targeted therapy [9] [13] |

| DISCO Tissue Clearing Reagents | Tissue transparency for whole-organism imaging | Urea-free formulation, reduced DCM incubation [9] | Whole-body nanocarrier tracking, single-cell resolution imaging [9] |

| DNA Origami Structures | Programmable nanocarriers | Customizable structure, precise functionalization [13] | Targeted immune cell delivery, programmable drug release [13] |

| Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs) | Gene therapy delivery vehicles | Tissue-specific tropism, high transduction efficiency [9] | Gene therapy development, tissue-specific targeting [9] [13] |

| Quantitative Phase Imaging (QPI) | Label-free cell imaging | Refractive index measurement, non-destructive [24] | Cell dynamics study, drug-cell interactions [24] |

U-Net Architecture Selection Guidelines

Table: Task-Specific 3D U-Net Architecture Recommendations

| Task Characteristic | Recommended Architecture | Performance Benefit | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-resolution images (voxel spacing <0.8mm) | Increased stages (S5, S6) | Significant improvement (p<0.05) [25] | Moderate increase (10-20% per stage) [25] |

| High label complexity (>10 classes) | Wider networks (W32, W64) | Substantial improvement [25] | Significant increase (~2× per width doubling) [25] |

| Anatomically regular structures (sphericity >0.6) | Deeper networks (D3) | Strong benefit [25] | Moderate increase (30-40%) [25] |

| Resource-constrained environments | GA-UNet or smaller U-Net variants | Competitive performance with 0.24%-0.67% parameters [26] | Drastic reduction (up to 8.8× faster inference) [26] [25] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key composition factors that influence nanocarrier encapsulation efficiency and biodistribution? The composition of nanocarriers is a critical determinant of their performance. For Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), the four-component system allows for precise tuning. The ionizable lipid (typically ~50 mol%) is crucial for nucleic acid encapsulation and endosomal escape, while the PEG-lipid (as low as 0.5-1.5 mol%) controls nanoparticle size and stability, and helps prolong circulation time. Helper phospholipids (e.g., DSPC, ~10 mol%) and cholesterol (~38-39 mol%) contribute to the structural integrity and stability of the particle, facilitating stable encapsulation and reducing drug leakage [28] [29]. For other nanocarriers like DNA origami, the sequence design and incorporation of stabilizing elements (like ITR hairpins) are key for maintaining integrity and enabling gene expression [30].

Q2: How can I accurately quantify nanocarrier biodistribution and off-target effects at single-cell resolution? Conventional whole-body imaging techniques like bioluminescence often lack the sensitivity and resolution for low-dose studies (e.g., vaccine doses) and cannot identify individual targeted cells. The SCP-Nano pipeline overcomes this by combining an optimized tissue-clearing method (a refined DISCO protocol) with light-sheet microscopy and a dedicated deep-learning analysis model (based on a 3D U-Net architecture). This integrated approach allows for the mapping and quantification of fluorescence-labeled nanocarrier biodistribution throughout an entire mouse body at single-cell resolution, identifying millions of individual targeting events with high sensitivity [9].

Q3: Why is my DNA origami failing to express delivered genes in mammalian cells? A primary prerequisite for gene expression from DNA origami is the unfolding of the nanostructure within the intracellular environment to make the encoded gene accessible. If your origami is too stable, for instance, through internal cross-linking (e.g., UV point welding), gene expression can be almost completely suppressed. Ensure that your origami design can denature inside the cell. Furthermore, gene expression efficiency can be significantly enhanced by incorporating specific functional sequences into your synthetic scaffold design, such as virus-inspired inverted terminal repeat (ITR) hairpin motifs, Kozak sequences, and woodchuck post-transcriptional regulatory elements (WPRE) [30].

Q4: What strategies can improve the endosomal escape of non-viral nanocarriers? Endosomal sequestration remains a major barrier. Several strategies exist, often centered on the design of ionizable lipids in LNPs, which become positively charged in the acidic endosomal environment, promoting membrane disruption [28]. Recent research shows that modifying helper components can also be highly effective. For example, replacing standard cholesterol in LNPs with natural analogues bearing a C-24 alkyl chain (e.g., β-sitosterol) can create morphologically distinct nanoparticles (e.g., polyhedral vs. spherical) that exhibit enhanced intracellular diffusivity and more efficient endosomal escape, leading to dramatically higher transfection [29]. For DNA origami, functionalization with endosomolytic agents or pH-responsive elements can be explored.

Q5: How can I achieve tissue-specific targeting with my nanocarrier? Targeting can be passive or active. Passive targeting, such as the natural accumulation of some LNPs in the liver and spleen, can be influenced by particle size and surface properties like PEGylation [28] [31]. Active targeting involves functionalizing the nanocarrier surface with targeting moieties that bind to receptors on specific cells. This is a universal strategy applicable to most nanocarrier types. Examples include using antibodies, aptamers (e.g., MUC-1 aptamer for breast cancer cells), or peptides (e.g., cell-penetrating peptides) on the surface of LNPs, DNA origami, gold nanoparticles, or other nanocarriers [32] [33]. Note that in vivo, a protein corona can form on the nanocarrier, which may mask these targeting ligands and alter biodistribution [9].

Q6: What are the cargo size limitations for different nanocarriers, and how can I work around them? Cargo capacity varies significantly and is a key factor in nanocarrier selection. The table below summarizes the limitations and common solutions.

| Nanocarrier | Typical Cargo Capacity | Strategies to Overcome Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Adeno-associated Viruses (AAVs) | ~4.7 kb [34] | Use smaller Cas protein orthologs (e.g., Cas12a); split cargo into dual/triple AAVs; deliver only sgRNA to Cas-expressing cells. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | High for mRNA; varies for type [31] | Optimize lipid composition and N:P ratio for different cargo sizes (e.g., saRNA, plasmid DNA). |

| DNA Origami | Up to ~10 kb or more (scaffold) [32] | Use custom-sequence scaffolds; design multimeric "brick" systems for larger genetic circuits [30]. |

| Adenoviral Vectors (AdVs) | Up to ~36 kb [34] | The large capacity generally avoids the need for workarounds for most CRISPR cargos. |

| Lentiviral Vectors (LVs) | No strict size limit [34] | The large capacity generally avoids the need for workarounds for most CRISPR cargos. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Transfection or Gene Expression Efficiency

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Inefficient Endosomal Escape. The nanocarrier is trapped and degraded in the endolysosomal pathway.

- Solution for LNPs: Screen or design novel ionizable lipids with improved endosomolytic activity. Consider incorporating cholesterol analogues like β-sitosterol, which has been shown to enhance transfection by up to 32-fold in some systems by altering intracellular trafficking and promoting escape [29].

- Solution for Polyplexes/DNA Origami: Incorporate endosomolytic peptides or polymers (e.g., polyethylenimine) into the design. Ensure the carrier can destabilize membranes at low pH.

Cause: Poor Cellular Uptake.

Cause: Nanocarrier Does Not Unpack its Payload.

- Solution for DNA Origami: The structure must unfold to express its gene. Avoid over-stabilization through excessive cross-linking. Designs that are stable in circulation but disassemble under intracellular conditions (e.g., in a reductive environment) are ideal [30].

Cause: Low Encapsulation Efficiency.

- Solution for LNPs: Optimize formulation parameters. Use microfluidic mixing for highly reproducible, homogeneous LNPs with >90% encapsulation efficiency, instead of manual methods like thin-film hydration [28]. Adjust the ratio of ionizable lipid to nucleic acid.

Issue 2: High Cytotoxicity or Immunogenicity

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Cationic Lipid-Induced Toxicity.

- Solution for LNPs: Replace permanently cationic lipids with ionizable lipids, which are neutral at physiological pH (reducing toxicity) but become positively charged in acidic endosomes (facilitating escape) [28].

Cause: Immune Recognition of Viral Vectors.

- Solution for AAVs/AdVs: Utilize different serotypes with lower seroprevalence. Consider using virus-like particles (VLPs), which are empty viral capsids that lack the viral genome, reducing immunogenicity and safety concerns associated with full viral vectors [34].

Cause: Non-Specific Interactions.

Issue 3: Inefficient Co-delivery of Multiple Components

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Stoichiometric Imbalance.

- Solution: Use a single nanocarrier system designed for multiplexing. DNA origami "bricks" that self-assemble into higher-order structures, with each brick encoding a different gene, enable stoichiometrically controlled co-delivery and expression, overcoming the limitations of Poisson distribution in co-transfection [30].

- Solution for CRISPR RNP Delivery: Co-encapsulate the Cas protein and guide RNA as a pre-formed ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex within a single LNP, ensuring they are delivered to the same cell simultaneously [31].

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from recent research to aid in experimental design and benchmarking.

Table 1: Impact of Cholesterol Analogues on LNP Transfection Efficiency (Based on [29])

| Cholesterol Analogue | Key Structural Difference | mRNA Encapsulation | Relative Transfection Efficiency (vs. Cholesterol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol (Control) | N/A | ~94% | 1.0x |

| β-Sitosterol | C-24 ethyl group | Comparable to control | Substantially improved (up to 32-fold with some ionizable lipids) |

| Stigmasterol | C-24 ethyl + C-22 double bond | Lower than control | 1.6x |

| Vitamin D2/D3 | Modified ring structure (Body) | High | Poor |

| Group III Analogs | Tail modified into a 5th ring | Limited | Poor |

Table 2: Performance of LNP Formulation Methods (Based on [28])

| Formulation Method | Particle Size Control | Homogeneity (PDI) | Encapsulation Efficiency | Scalability & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microfluidics | High (e.g., 50-200 nm) | High (<0.2) | High (≥90%) | Gold standard for R&D; highly controllable and repeatable. |

| Macrofluidics (T-junction) | Good | Good | High | Suitable for large-scale production (e.g., vaccines); requires larger volumes. |

| Manual Mixing (Pipette) | Low | Low (Highly variable) | Low | Suitable only for basic proof-of-concept; not reproducible. |

| Thin-Film Hydration | Low | Low | Low | Easy to use but poor size control and encapsulation. |

| High-Energy Methods | Low | Low | Low | Risk of damaging delicate nucleic acids. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: SCP-Nano Pipeline for Whole-Body, Single-Cell Biodistribution Mapping

This protocol enables the sensitive detection and quantification of nanocarrier targeting events across the entire body of a mouse at single-cell resolution [9].

- Nanocarrier Administration: Administer your fluorescence-labeled nanocarrier (e.g., LNP, AAV, liposome) to mice via the desired route (e.g., intravenous, intramuscular) at the relevant dose (validated down to 0.0005 mg kg⁻¹).

- Tissue Clearing (Optimized DISCO):

- Perfuse and fix the mice.

- Key Optimization: Use a refined DISCO clearing protocol that omits urea and sodium azide and reduces dichloromethane (DCM) incubation time to preserve the fluorescence signal of tagged mRNAs or labels throughout the body.

- Whole-Body Imaging: Image the cleared whole mouse bodies using light-sheet fluorescence microscopy at a high resolution (approximately 1–2 µm lateral, 6 µm axial).

- AI-Based Quantification (SCP-Nano Deep Learning Pipeline):

- Data Preparation: Partition the whole-body imaging data into manageable 3D patches.

- Model Application: Process the data using the pre-trained 3D U-Net deep learning model. This model was trained on a diverse dataset of tissues annotated via a virtual reality (VR) system for superior accuracy.

- Analysis: The pipeline identifies each targeted cell/cluster instance, calculating its size and intensity contrast. This allows for organ-level and single-cell-level quantification of nanocarrier delivery.

Protocol 2: Assessing Gene Expression from DNA Origami in Mammalian Cells

This protocol outlines key steps for designing and testing DNA origami for gene delivery and expression [30].

- Design and Production:

- Scaffold Design: Create a custom, circular single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) scaffold that encodes your gene of interest (e.g., EGFP) under a mammalian promoter (e.g., CMV). Incorporate enhancing sequences like Kozak, WPRE, and ITR-like hairpins.

- Staple Design: Design staple strands to fold the scaffold into the desired shape. For enhanced expression, use long, continuous staples with no crossovers in the promoter and polyA regions to create stable double-stranded DNA in these key areas.

- Folding and Purification: Anneal the scaffold and staple strands to form the DNA origami object. Purify the correctly folded structures.

- Cell Transfection:

- Use electroporation (e.g., NeonTM Transfection System) for direct delivery into cells, as traditional cuvette electroporation may cause origami aggregation.

- A control with a non-annealed mixture of scaffold and staples can be used to compare expression from the unstructured components.

- Validation of Unfolding:

- To confirm that unfolding is necessary for expression, create a control group of origami that are topologically locked via UV point welding. Expect to see a near-complete suppression of gene expression in this group compared to the non-crosslinked origami.

- Expression Analysis: Measure transfection efficiency (percentage of fluorescent cells) and gene expression efficiency (mean fluorescence intensity) using flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy.

Visualization Diagrams

Nanocarrier Intracellular Journey Pathway

SCP-Nano Experimental Workflow

DNA Origami Gene Expression Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Cationic Lipids (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA) | Core component of LNPs; encapsulates nucleic acids and enables endosomal escape via charge shift [28] [29]. | pKa is a critical parameter; must be tunable for optimal performance in different applications. |