Navigating FDA Regulatory Pathways for Nanotechnology Products: A 2025 Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the U.S.

Navigating FDA Regulatory Pathways for Nanotechnology Products: A 2025 Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) regulatory framework for nanotechnology products. It covers the foundational principles of the FDA's science-based, product-specific approach, details the methodological considerations for product development and submission, offers strategies for troubleshooting common regulatory challenges, and explains validation through expedited programs and real-world case studies. The content is designed to help innovators efficiently navigate the regulatory process, from early development to market approval, for a wide range of nanotech applications in drugs, biologics, and other regulated products.

Understanding the FDA's Regulatory Framework for Nanotechnology

The FDA's Product-Focused and Science-Based Policy Philosophy

A technical guide for navigating regulatory science for nanotechnology products

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates a wide range of products that may utilize nanotechnology or contain nanomaterials, from drugs and devices to foods and cosmetics. The agency's approach is product-focused and science-based, meaning technical assessments consider the effects of nanomaterials in the specific biological and mechanical context of each product and its intended use [1]. This resource provides targeted guidance for researchers and developers working within this regulatory framework.

Frequently Asked Questions: Navigating FDA Nanotechnology Regulation

Q1: How does the FDA define nanotechnology for regulatory purposes? The FDA does not rely on a single, rigid definition. Instead, it focuses on whether a material or product is engineered to have at least one external dimension, or an internal or surface structure, in the nanoscale range (approximately 1–100 nm). More importantly, the agency considers whether the engineered material exhibits properties or phenomena attributable to its dimension(s), including physical or chemical properties or biological effects that differ from those of larger-scale counterparts [2]. The evaluation is based on the product's specific characteristics and intended use.

Q2: Does the FDA have a unique regulatory pathway for nanotechnology products? No. The FDA regulates nanotechnology products under its existing statutory authorities and in accordance with the specific legal standards applicable to each type of product (e.g., drug, device, cosmetic) [1] [2]. The regulatory pathway is determined by the product's classification and its intended use, not solely by the presence of nanotechnology.

Q3: What is the most critical step for developers of an NHP (Nanotechnology-Enabled Health Product) during early development? The FDA strongly encourages early consultation with the agency. Engaging with the FDA early in the product development process facilitates a mutual understanding of the specific scientific and regulatory issues. This allows developers to clarify the methodologies and data needed to meet safety, effectiveness, and other regulatory obligations [1] [2].

Q4: What are the key regulatory science questions the FDA is trying to answer for NHPs? The FDA's nanotechnology regulatory science research focuses on two primary areas [2]:

- Understanding the interactions of nanomaterials with biological systems.

- Assessing the adequacy of testing approaches for evaluating the safety, effectiveness, and quality of products containing nanomaterials.

Q5: How does the FDA's "product-focused" approach impact my regulatory strategy? This approach means that data requirements are not one-size-fits-all. Your regulatory strategy and the data you generate must be tailored to your specific product. A drug delivery nanoparticle will be held to different standards than a nanocoat ed surgical implant, even if they incorporate the same nanomaterial, because the biological context, route of administration, and intended use differ [1].

Regulatory Science Research Priorities

The FDA invests in a robust regulatory science program to enhance its capabilities for assessing nanotechnology products. The table below summarizes key research priority areas that inform the agency's evaluations.

| Research Priority Area | Key Questions for Investigators | Relevant Product Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical Characterization | What parameters must be defined to establish a nanomaterial's identity? How do properties change in biological environments? | Drugs, Biologics, Devices, Food Additives |

| Toxicology & Biocompatibility | How do nanomaterials interact with cells and organ systems? What are the appropriate toxicological endpoints? | Drugs, Devices, Cosmetics |

| Safety & Effectiveness Evaluation | Are standard testing models adequate? What new methods are needed to demonstrate clinical benefit? | Drugs, Devices, Biologics |

| Quality & Manufacturing Control | How can manufacturing consistency be ensured? What controls are critical for batch-to-batch reproducibility? | Drugs, Biologics, Devices |

Experimental Protocol: Critical Physicochemical Characterization of Nanomaterials

A foundational step in developing an NHP is a comprehensive characterization of the nanomaterial's physicochemical properties. This data is essential for understanding its behavior, stability, and biological interactions and is a core requirement in regulatory submissions.

Objective

To systematically identify and quantify the key physicochemical parameters of a nanomaterial to establish its critical quality attributes (CQAs) for regulatory evaluation.

Materials and Reagents

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Characterization |

|---|---|

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument | Measures hydrodynamic diameter (size) and particle size distribution (polydispersity index) in a liquid suspension. |

| Zeta Potential Analyzer | Determines the surface charge, which predicts colloidal stability and interaction with biological membranes. |

| Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM) | Provides high-resolution imaging for direct visualization of particle size, morphology, and structure. |

| Surface Area and Porosity Analyzer (BET) | Quantifies specific surface area, a key parameter influencing reactivity, dissolution, and drug loading capacity. |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Analyzes elemental composition and chemical state of the material's surface. |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Used to quantify drug loading and encapsulation efficiency for nanocarrier systems. |

| Stable Biological Media (e.g., PBS, cell culture media) | Used to assess particle stability and agglomeration behavior in physiologically relevant conditions. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a standardized suspension of the nanomaterial in a relevant solvent (e.g., water, buffer) at a defined concentration. Use sonication or other methods to ensure a monodisperse suspension before analysis.

- Size and Distribution Analysis:

- Utilize Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to measure the hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI). A PDI value below 0.2 is generally considered monodisperse.

- Validate DLS data with a direct imaging technique like Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) to confirm size and assess morphology (e.g., spherical, rod-shaped).

- Surface Charge Measurement: Use a Zeta Potential Analyzer to determine the surface charge. Measurements should be performed in different media (e.g., water, PBS) to predict stability and behavior in biological fluids.

- Surface and Structural Analysis:

- Perform Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis to determine the specific surface area.

- Use X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to identify the elemental and chemical composition of the particle surface.

- Drug Loading Assessment (for nanocarriers): For drug-loaded nanoparticles, use a validated HPLC method to separate free drug from the nanocarrier, allowing for calculation of drug loading capacity and encapsulation efficiency.

- Stability in Biological Media: Incubate the nanomaterial in biologically relevant media (e.g., PBS with serum proteins) and monitor changes in size and zeta potential over time (e.g., 0, 1, 4, 24 hours) using DLS to assess agglomeration or degradation.

The workflow for this characterization process is outlined below.

Data Interpretation and Regulatory Significance

Regulatory assessments rely on a clear demonstration of product quality and consistency. A well-characterized nanomaterial, with CQAs that are tightly controlled, is critical for establishing a valid safety profile. This data forms the foundation for all subsequent non-clinical and clinical studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Characterization Parameters

For any NHP, regulators will expect a comprehensive dataset detailing the following parameters. This list serves as a checklist for your development work.

| Parameter | Description | Example Technique(s) | Regulatory Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size & Distribution | Hydrodynamic diameter & polydispersity. | DLS, TEM, SEM | Affects biodistribution, clearance, and toxicity [3]. |

| Surface Charge | Zeta potential in relevant media. | Zeta Potential Analyzer | Predicts colloidal stability & interaction with cells [3]. |

| Surface Chemistry | Functional groups & coating composition. | XPS, FTIR | Influences protein corona formation & biological fate [3]. |

| Surface Area | Specific surface area per mass unit. | BET Analysis | Critical for understanding reactivity & dose [3]. |

| Morphology | Particle shape & physical structure. | TEM, SEM | Impacts cellular uptake & biological activity [3]. |

| Drug Release | Release kinetics in physiological conditions. | Dialysis, HPLC | Core to demonstrating controlled release function [3]. |

| Stability | Shelf-life & in-media behavior. | DLS, HPLC | Required to prove product quality & performance during use. |

| Elemental Impurities | Quantification of catalytic residues. | ICP-MS | Required for safety assessment of the manufacturing process. |

| Crystallinity | Physical state of the material (e.g., amorphous, crystalline). | XRPD | Can impact stability, dissolution, and biological performance. |

Troubleshooting Common Nanomaterial Characterization Issues

Problem: Inconsistent Sizing Results Between DLS and TEM

- Cause: DLS measures the hydrodynamic diameter (core + solvation layer) in a liquid state, while TEM provides a dry-state image of the core particle.

- Solution: This discrepancy is expected. Use DLS for stability and behavior in solution, and TEM to confirm core size and morphology. Report both datasets with a clear explanation.

Problem: Rapid Agglomeration in Biological Media

- Cause: Insufficient surface charge or the presence of proteins causing bridging flocculation.

- Solution: Reformulate to increase zeta potential magnitude (e.g., > ±20 mV). Consider modifying the surface with steric stabilizers like polyethylene glycol (PEG).

Problem: Low Drug Loading Capacity in Nanocarrier

- Cause: Poor compatibility between the drug and the carrier matrix, or inefficient encapsulation method.

- Solution: Optimize the drug-to-carrier ratio and the manufacturing process (e.g., solvent displacement, emulsification). Explore different nanocarrier materials.

For further information, the FDA provides a comprehensive search portal for its official guidance documents [4], and encourages direct contact for specific questions via the Office of Policy at 301-796-4830 [1].

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the FDA's regulatory definition of a "nanomaterial"? The FDA has not established a single, rigid regulatory definition for the term "nanomaterial" [5] [6]. Instead, the agency uses a flexible, two-point framework to determine whether an FDA-regulated product involves the application of nanotechnology [6].

If there's no definition, how does the FDA identify nanomaterials? The FDA uses two "Points to Consider" for identification. A product may involve the application of nanotechnology if it meets either of the following criteria [6]:

- It is engineered to have at least one external dimension, or an internal or surface structure, in the nanoscale range (approximately 1 nm to 100 nm).

- It is engineered to exhibit properties or phenomena (e.g., physical, chemical, or biological effects) attributable to its dimension(s), even if these dimensions fall outside the nanoscale range, up to one micrometer (1,000 nm).

Are naturally occurring nanoscale materials (like proteins) considered? The FDA's guidance is primarily intended for engineered nanomaterials. It distinguishes between materials that have been deliberately manipulated to have nanoscale dimensions and those that naturally exist at the nanoscale, such as proteins or other biological materials, which are not explicitly considered nanomaterials per the guidance [5] [6].

What about incidental nanoparticles from manufacturing? The guidance does not pertain to products that contain incidental nanoscale particles generated from conventional manufacturing processes or storage [5] [6]. The focus is on intentionally engineered materials and their properties.

Why is particle size alone not sufficient for identification? Some materials can exhibit dimension-dependent properties or phenomena, such as increased bioavailability or altered chemical reactivity, even at sizes larger than 100 nm. The second "Point to Consider" ensures these materials are also evaluated for potential unique safety and efficacy profiles [6] [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges in Nanomaterial Identification and Characterization

Problem 1: Determining if a material with a size >100 nm falls under FDA nanotechnology considerations.

- Potential Cause: The material exhibits dimension-dependent properties or phenomena, as described in the FDA's second "Point to Consider" [6].

- Solution:

- Investigate Properties: Systematically test whether the material exhibits properties that differ from its larger-scale counterparts. Key properties to investigate include [6]:

- Increased chemical or biological activity

- altered electrical or optical activity

- Increased structural integrity

- Changed magnetic properties

- Link to Dimensions: Confirm that these novel properties are a direct result of the material's engineered dimensions and not just its chemical composition.

- Consult FDA: It is recommended that sponsors consult with the FDA early in the development process if they believe their product may involve the application of nanotechnology [6].

- Investigate Properties: Systematically test whether the material exhibits properties that differ from its larger-scale counterparts. Key properties to investigate include [6]:

Problem 2: A drug product's critical quality attributes (CQAs) change during scale-up.

- Potential Cause: Nanomaterials are often sensitive to process conditions and manufacturing changes, which can affect particle size, size distribution, and other critical attributes [5].

- Solution:

- Early Identification: Identify CQAs early in development. These are physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological properties that should be within an appropriate limit to ensure the desired product quality [5].

- Implement Controls: Develop and implement appropriate in-process controls during manufacturing to ensure consistency.

- Stability Testing: Follow stability testing processes that monitor for nanomaterial-specific changes, such as aggregation, agglomeration, or changes in morphology [5].

Problem 3: Difficulty in characterizing nanomaterial size and properties.

- Potential Cause: Standard analytical techniques, like light microscopy, are often inadequate for resolving materials at the nanoscale due to the diffraction limit of light [5].

- Solution: Employ specialized techniques suited for nanomaterial characterization. The table below summarizes key parameters and common methods as outlined in ISO standards [8].

Table 1: Key Physico-Chemical Characterization Parameters and Methods for Nanomaterials

| Parameter | Description | Relevance / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Size & Distribution | The average size and variability of particles in a population. | Affects biodistribution, bioavailability, and biological activity [5] [8]. |

| Aggregation/Agglomeration State | The tendency of particles to clump together. | Influences behavior, dose, and exposure [8]. |

| Shape | The physical form of the particles (e.g., spherical, rod-shaped). | Impacts cellular uptake and toxicity [8]. |

| Surface Area | The total surface area per unit mass. | Increased surface area can enhance reactivity and biological activity [8] [9]. |

| Surface Chemistry | The composition and properties of the material's surface. | Dictates interactions with biological systems (e.g., protein corona formation) [8]. |

| Surface Charge | The electrical charge on the particle's surface. | Affects colloidal stability, aggregation, and interaction with cell membranes [8]. |

| Solubility/Dispersibility | The ability to dissolve or form a stable suspension in a medium. | Critical for understanding fate, persistence, and exposure [8]. |

Problem 4: Designing a biocompatibility testing plan for a medical device containing nanomaterials.

- Potential Cause: Standard biocompatibility tests (ISO 10993 series) may require adaptation for nanomaterials due to their unique kinetic properties and potential for assay interference [8].

- Solution: Follow a two-step process as guided by ISO/TR 10993-22:

- Comprehensive Characterization: Perform a thorough physico-chemical characterization of the nanomaterial using the parameters in Table 1 before any biological testing [8].

- Adapted Biological Testing: Modify standard test protocols to account for nanomaterial behavior. The table below outlines key considerations for common test endpoints.

Table 2: Key Considerations for Biological Testing of Nanomaterial-Containing Medical Devices

| Test Endpoint | Testing Considerations | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxicity | Use several test methods (e.g., with phagocytic and non-phagocytic cell lines). | Nanomaterials are generally taken up by cells; assay interferences are possible; kinetics depend on size and agglomeration [8]. |

| Sensitization | Standard in vivo assays (like GPMT or LLNA) might not be effective. | The skin's barrier function may prevent nano-objects from reaching target immune cells [8]. |

| Hemocompatibility | Must evaluate complement system activation. | Nanomaterials can cause abnormal complement activation, leading to significant inflammatory reactions; high surface area can adsorb serum proteins, distorting results [8]. |

| Systemic Toxicity | Focus on tissues like the liver, spleen, and kidneys. Consider particle number and surface area as dose metrics, not just mass. | Nano-objects can distribute throughout the body, with concern for accumulation and biopersistence in the mononuclear phagocyte system [8]. |

| Genotoxicity | The bacterial reverse mutation test (Ames test) is not appropriate for free nano-objects; use mammalian cell systems instead. | Uncertainty about whether bacteria can uptake nano-objects and thus expose DNA [8]. |

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Regulatory Tools

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| FDA Guidance "Drug Products... Nanomaterials" | Provides specific considerations for the development, manufacturing, and evaluation of human drug products containing nanomaterials [5] [10]. |

| ISO/TR 10993-22 Guidance | Offers detailed protocols for the biological evaluation of medical devices composed of or containing nanomaterials [8]. |

| HEPA-Filtered Local Exhaust Ventilation | An engineering control (e.g., fume hoods, glove boxes) to reduce potential inhalation exposure to aerosolized nanoparticles in the laboratory [9]. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | A common technique used to determine the hydrodynamic size and size distribution of nanoparticles in suspension. |

| Reference Nanomaterials | Standardized materials used to calibrate equipment and validate test methods, though their availability is still a developing area [7]. |

| OECD Test Guidelines for Nanomaterials | Provide internationally agreed-upon methods for testing the safety of nanomaterials, supporting the Mutual Acceptance of Data [7]. |

Experimental Workflow: Applying the FDA's Points to Consider

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for identifying if a material falls under the FDA's nanotechnology considerations, integrating characterization and testing steps.

Technical Support Center: Navigating FDA Nanotechnology Regulations

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Regulatory Challenges

Issue 1: Determining When a Product Involves Nanotechnology

- Problem: Researchers are uncertain whether their product meets FDA's criteria for nanotechnology oversight.

- Solution: Apply FDA's two "Points to Consider" [6]:

- Engineered materials with at least one external dimension, internal structure, or surface structure between 1-100 nm

- Materials engineered to exhibit properties or phenomena attributable to their dimension(s), even outside the 1-100 nm range (up to 1000 nm)

- Required Documentation: Comprehensive characterization data including size distribution, surface charge, and stability profiling.

Issue 2: Selecting the Correct Premarket Pathway

- Problem: Confusion about whether a nanotech product requires premarket approval or can use existing regulatory pathways.

- Solution Matrix:

| Product Type | Premarket Review Required? | Key Regulatory Standard | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Drugs | Yes (NDA) [1] | Safety + Effectiveness [1] | Clinical data, nano-specific toxicology |

| Medical Devices | Varies by class [11] | Risk-based classification [11] | Performance testing, biocompatibility |

| Food Additives | Yes [1] | Reasonable certainty of no harm [1] | Toxicity studies, consumption patterns |

| Cosmetics | No (voluntary consultation) [1] | Safety assurance [1] | Limited safety data, ingredient listing |

| Dietary Supplements | No (except new ingredients) [1] | Safety assurance [1] | History of use, composition data |

Issue 3: Demonstrating Substantial Equivalence for Nanotech Devices

- Problem: Difficulty finding appropriate predicates for 510(k) submissions due to novel nanoscale properties.

- Solution Options:

Experimental Protocols for Regulatory Submissions

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Nanomaterial Characterization

- Objective: Fully characterize physicochemical properties to determine regulatory status

- Methodology:

- Size Distribution: Dynamic light scattering, electron microscopy

- Surface Properties: Zeta potential, surface area analysis

- Stability: Accelerated stability studies under intended storage conditions

- Batch-to-Batch Variability: Minimum of 3 manufacturing lots

- Regulatory Reference: FDA's 2014 nanotechnology guidance [6]

Protocol 2: Nano-Specific Toxicology Assessment

- Objective: Identify unique biological effects of nanoscale materials

- Methodology:

- Biodistribution Studies: Radiolabeling and tissue distribution analysis

- Immune Response Evaluation: Complement activation, cytokine profiling

- Cellular Uptake Assessment: Confocal microscopy, flow cytometry

- Traditional Toxicology: Acute and chronic toxicity per ICH guidelines

- Application: Required for all injectable and systemic delivery nanotechnologies

Table 1: Market Data and Regulatory Maturity by Sector (2024)

| Sector | Global Revenue (USD Billion) | Maturity Level | FDA Regulatory Clarity | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanomedicine | $12.4 [13] | High [13] | Established pathways for drug delivery [14] | Generic equivalence, long-term safety [14] |

| Semiconductor Manufacturing | $22.1 [13] | High [13] | Device classification framework [11] | Rapid technological evolution |

| Food Ingredients | Not specified | Low [15] | Voluntary GRAS notification [15] | Lack of mandatory oversight [15] |

| Cosmetics | Not specified | Low [1] | Post-market surveillance [1] | No premarket approval required |

Table 2: Medical Device Classification and Pathways

| Device Class | Risk Level | Regulatory Pathway | Typical Timeline | Nano-Specific Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | Minimal [11] | General controls, mostly exempt [11] | 1-3 months [11] | May require additional characterization |

| Class II | Moderate [11] | 510(k) substantial equivalence [11] | 6-12 months [11] | Enhanced performance data, special controls |

| Class III | High [11] | Premarket Approval (PMA) [11] | 2-5 years [11] | Clinical data, complete nano-toxicology profile |

| De Novo | Low-Moderate, novel [12] | Risk-based classification [12] | 120-150 days [11] | First-of-its-kind nanotechnology evaluation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Nanotechnology Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function | Regulatory Application |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Light Scattering Standards | Size distribution calibration | Required for all nanomaterial characterization [6] |

| Zeta Potential Reference Materials | Surface charge validation | Critical for stability assessment and immune response prediction |

| Complement Activation Assay Kits | Immunotoxicity screening | Essential for injectable nanomedicines [14] |

| Tissue Distribution Tracers | Biodistribution studies | Required for all systemic administration products |

| Reference Nanomaterials | Method validation and comparison | Supports substantial equivalence demonstrations |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How does FDA determine if my product requires nano-specific regulation? A: FDA applies a two-point framework considering both size (1-100 nm) and dimension-dependent properties, even for materials up to 1000 nm [6]. The key is whether nanotechnology application changes product safety or effectiveness.

Q2: What are the most common mistakes in nanotech regulatory submissions? A: The most frequent issues include inadequate material characterization, insufficient batch-to-batch reproducibility data, and lack of nano-specific toxicology studies [14]. Early FDA consultation is recommended to avoid these pitfalls.

Q3: How do regulatory pathways differ between nanotech drugs and devices? A: Drugs require safety and effectiveness demonstration regardless of technology, while devices use risk-based classification [1]. Nanotech often pushes devices into higher classes or requires De Novo classification [12].

Q4: Are generic nanotech products eligible for abbreviated pathways? A: Yes, but demonstrating sameness is challenging. FDA issues product-specific guidances addressing complex nanotech generics, requiring extensive characterization and bioequivalence data [16] [14].

Q5: What post-market requirements apply to nanotechnology products? A: All products face ongoing monitoring, but nanotech may require additional surveillance for long-term effects, immunogenicity, and unique toxicity profiles [1] [14].

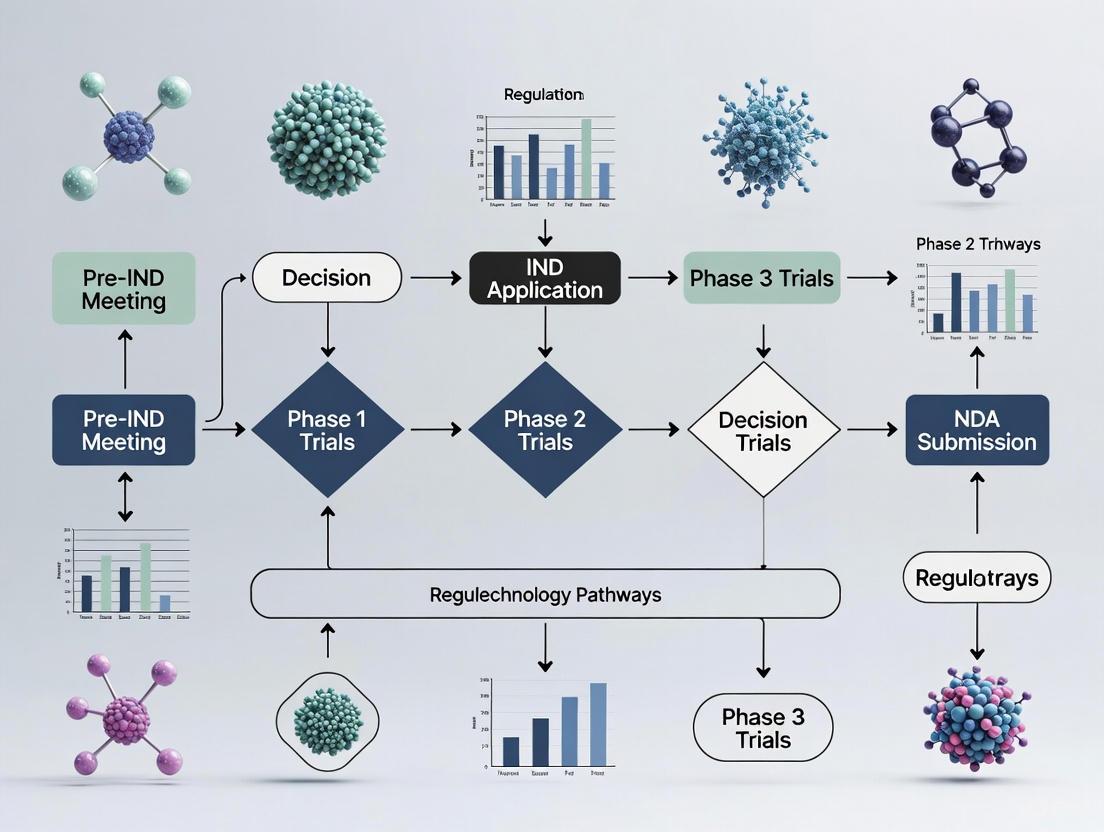

Workflow Visualization: Regulatory Pathway Decision Matrix

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for nanotechnology product regulatory pathways

Experimental Protocol: Nano-Characterization for Regulatory Compliance

Protocol 3: Standardized Nanomaterial Documentation Package

- Purpose: Create comprehensive documentation meeting multiple regulatory requirements

- Materials:

- Analytical grade reference standards

- Multiple manufacturing batches (minimum 3)

- Stability testing equipment

- Cell-based assay systems for toxicity screening

- Procedure:

- Physicochemical Characterization: Complete profiling of size, shape, surface, and composition

- Manufacturing Controls: Document process parameters and quality controls

- Stability Assessment: Real-time and accelerated conditions

- Biological Performance: Link material properties to biological effects

- Deliverable: Integrated summary bridging material science and biological data

This technical support resource will be updated quarterly as FDA issues new product-specific guidances and nanotechnology regulations evolve. Researchers should consult the most recent FDA guidance documents and engage in early consultations for novel technologies.

The Role of the 2007 Nanotechnology Task Force Report and Subsequent Guidance

In 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) formed an internal Nanotechnology Task Force to address the regulatory and scientific questions presented by the emergence of nanotechnology in FDA-regulated products [17]. The Task Force was charged with determining regulatory approaches that would enable the continued development of innovative, safe, and effective products that use nanoscale materials [17]. Its landmark report, issued in July 2007, established the FDA's initial policy foundation for evaluating the safety, effectiveness, and regulatory status of nanotechnology products [17] [2].

This technical support center distills the key outcomes of that report and the subsequent guidance documents into an actionable format for researchers and scientists. The FAQs and guides below are designed to help you navigate the specific regulatory and experimental issues you might encounter during the development of nanotechnology-based drugs, biological products, and devices.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What was the main conclusion of the 2007 Nanotechnology Task Force Report regarding the FDA's regulatory authority?

The Task Force concluded that the FDA's existing authorities are "generally comprehensive" for products subject to premarket authorization (such as drugs, biologics, and devices) [17]. This means the agency has the ability to obtain detailed scientific information needed for review. However, oversight is less comprehensive for products not subject to premarket review, such as dietary supplements and cosmetics. The report therefore recommended issuing additional guidance to improve predictability and ensure public health protection [17].

Q2: Does the FDA have a singular, strict definition of "nanomaterial" for regulatory purposes?

No. The FDA has not established a single rigid regulatory definition [6]. Instead, its guidance provides two flexible "Points to Consider" to help identify if a product involves the application of nanotechnology [6]:

- Whether a material or end product is engineered to have at least one external dimension, or an internal or surface structure, in the nanoscale range (approximately 1 nm to 100 nm).

- Whether a material or end product is engineered to exhibit properties or phenomena (including physical, chemical, or biological effects) that are attributable to its dimension(s), even if these dimensions fall outside the nanoscale range, up to one micrometer (1,000 nm).

Q3: I am developing a drug product that contains a nanomaterial. What is the most critical recent guidance I should consult?

You should consult the April 2022 final guidance: "Drug Products, Including Biological Products, that Contain Nanomaterials - Guidance for Industry" [10]. This product-specific document provides the FDA's current thinking on the development of human drug products where a nanomaterial is present in the finished dosage form, whether as an active or inactive ingredient.

Q4: What is the FDA's overall philosophy for regulating nanotechnology products?

The FDA maintains a product-focused, science-based regulatory policy [1] [2]. The agency does not categorically judge all nanotechnology products as inherently benign or harmful. Instead, technical assessments are product-specific, taking into account the effects of nanomaterials in the particular biological and mechanical context of each product and its intended use [1]. Regulation occurs under existing statutory authorities, in accordance with the specific legal standards for each product type [2].

Q5: What should I do if I am developing a complex product that combines a diagnostic device and a therapeutic nanomaterial?

The 2007 Task Force Report specifically highlighted such combination products as an area needing clarity [17]. It strongly recommended that manufacturers communicate with the FDA early in the development process to facilitate a mutual understanding of the scientific and regulatory issues for these highly integrated products [17] [18].

Troubleshooting Your Regulatory Pathway: A Guide for Researchers

Problem: Uncertainty about when a material is considered a "nanomaterial" under FDA guidance.

Application of the FDA's "Points to Consider"

This protocol will help you determine if your material meets the points to consider for an FDA-defined nanotechnology product, a crucial first step in planning your regulatory strategy [6].

- Objective: To systematically evaluate a material against the FDA's two Points to Consider to determine if it involves the application of nanotechnology.

- Experimental Rationale: Early identification allows for appropriate safety and efficacy testing and informs pre-submission meetings with the FDA.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Material Characterization:

- Use appropriate techniques (e.g., Dynamic Light Scattering, Electron Microscopy, Atomic Force Microscopy) to determine the physical dimensions of your material. Measure at least one external dimension.

- Decision Point: Is the material engineered to have at least one dimension in the range of approximately 1 nm to 100 nm?

- Result: If YES, the material satisfies Point to Consider 1. Proceed to investigate its biological and toxicological profile.

Property and Phenomenon Analysis:

- Even if the dimensions fall outside the 1-100 nm range (e.g., up to 1000 nm), investigate if the material exhibits dimension-dependent properties or biological effects.

- Compare the properties (e.g., chemical reactivity, magnetic, optical) and biological effects (e.g., altered bioavailability, tissue distribution, catalytic activity, toxicity) of your test material to its larger-scale counterpart with the same chemical composition.

- Decision Point: Are the observed properties or biological effects engineered and attributable to its dimension(s)?

- Result: If YES, the material satisfies Point to Consider 2.

Interpretation and Next Steps:

- An affirmative finding for either Point 1 or Point 2 suggests the product may involve the application of nanotechnology. This indicates a need for particular attention to identify and address potential implications for safety, effectiveness, and regulatory status [6].

- You should consult relevant product-specific FDA guidance documents and consider an early pre-submission meeting with the agency.

The following workflow diagram visualizes this decision-making process:

Problem: Determining the appropriate regulatory data for a drug product containing a nanomaterial.

Systematic Approach for Drug Developers

This methodology outlines the key considerations for planning the non-clinical studies needed to support an application for a drug or biological product containing nanomaterials [1] [10].

- Objective: To identify critical quality attributes and safety profiles of a nanomaterial-based drug product that may differ from conventional counterparts and require additional or modified testing.

- Experimental Rationale: The altered chemical, physical, or biological properties of nanomaterials can impact product quality, safety, and efficacy. A tailored testing strategy is essential [17] [2].

Key Experimental Considerations Table:

| Testing Category | Key Parameters to Investigate | Rationale & Regulatory Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical Characterization | Size and size distribution, surface charge (zeta potential), surface chemistry/reactivity, surface area, morphology, solubility, aggregation/agglomeration potential. | These parameters are fundamental as they influence biological interactions, biodistribution, and stability. The 2014 guidance emphasizes understanding dimension-dependent properties [6]. |

| Pharmacokinetics/Toxicokinetics | Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) profile; bioaccumulation potential in tissues; plasma protein binding. | Nanomaterials may exhibit altered ADME compared to small molecules or larger particles, affecting safety and efficacy. This is a core element of the regulatory science research plan [1] [2]. |

| Safety Pharmacology & Toxicology | Repeated-dose toxicity; assessment of organs that may accumulate the nanomaterial (e.g., RES organs); immunotoxicity; potential for local tolerance reactions. | The Task Force Report highlighted that properties affecting safety might be amplified at the nanoscale, meriting particular examination [17] [18]. |

| Product Quality & Manufacturing | Control of manufacturing process to ensure consistent attributes; product stability; sterility if applicable. | The 2022 drug product guidance expects rigorous quality control for products containing nanomaterials [10]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

When conducting experiments to characterize nanomaterials for regulatory submissions, several key types of reagents and materials are essential. The table below lists critical solutions and their functions in the context of FDA guidance.

Research Reagent Solutions for Nanomaterial Characterization

| Research Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Experimental Protocols |

|---|---|

| Standard Reference Materials | Used for calibration and validation of analytical instruments (e.g., DLS, NTA, SEM) to ensure accurate size and morphology measurements, which are critical for the "Points to Consider" [6]. |

| Cell Culture Models | Relevant in vitro models (e.g., primary cells, cell lines) are used to assess nanomaterial biocompatibility, cytotoxicity, and immunotoxicity as part of the safety profile [18]. |

| Biomolecule Assay Kits | Kits for quantifying proteins, cytokines, or markers of oxidative stress are used to evaluate biological effects and potential immunotoxicity of nanomaterials [1]. |

| Chromatography Columns | Specialized columns (e.g., SEC, HPLC) are used to analyze the stability of the nanomaterial formulation and to detect potential aggregation or release of encapsulated agents [10]. |

| Animal Disease Models | Relevant in vivo models are used to study the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and efficacy of the nanomaterial-based drug product, providing data for the benefit-risk assessment [1]. |

Key FDA Guidance Documents for Nanotechnology Products

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the FDA's general approach to regulating nanotechnology products? The FDA employs a product-focused, science-based regulatory policy for nanotechnology. The agency does not categorically judge all nanotechnology products as inherently benign or harmful. Instead, evaluations are product-specific, considering the unique properties and behaviors of nanomaterials within the particular biological and mechanical context of each product and its intended use. The FDA regulates nanotechnology products under existing statutory authorities, applying the specific legal standards applicable to each product type under its jurisdiction [1] [2].

Q2: Are there specific FDA guidance documents dedicated to nanotechnology? Yes, the FDA has issued several guidance documents specifically addressing nanotechnology. These represent the FDA's current thinking on nanotechnology application in regulated products and are issued as part of the ongoing implementation of recommendations from the FDA's 2007 Nanotechnology Task Force Report [19] [2]. The most significant recent guidance is "Drug Products, Including Biological Products, that Contain Nanomaterials - Guidance for Industry" issued in April 2022 [10].

Q3: What is the recommended particle size range for considering a material a nanomaterial according to FDA guidance? While the FDA has not established a rigid regulatory definition, the guidance considers materials with dimensions up to 1,000 nm (1 micron) to be nanomaterials when they are engineered to exhibit size-dependent properties or phenomena. This is particularly relevant when these properties differ from those observed at larger scales. For reference, a human hair is approximately 80,000-100,000 nanometers wide [5].

Q4: What are the key challenges in characterizing nanomaterials for regulatory submissions? Characterization challenges include:

- Measurement limitations: Standard light microscopes cannot resolve objects smaller than ~250 nm due to the diffraction limit, requiring specialized techniques [5].

- Size distribution: Particle size distribution may significantly affect desired product properties and must be carefully controlled [5].

- Stability issues: Nanomaterials may exhibit changes in size distribution, morphology, solid state, or tendency for aggregation/agglomeration during storage [5].

Q5: Does the FDA require premarket review for all products containing nanomaterials? Premarket review requirements depend on the product category:

- Premarket review required: New drugs, new animal drugs, biologics, food additives, color additives, certain human devices, and certain new dietary ingredients [1].

- Premarket review not required: Dietary supplements (except certain new dietary ingredients), cosmetics (except color additives), and conventional foods (except food or color additives). For these products, the FDA encourages voluntary early consultation before marketing [1].

Q6: What are Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) for nanomaterial-containing drug products? CQAs are physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological properties that must be within appropriate limits to ensure desired product quality. For nanomaterials, these typically include:

- Particle size and size distribution

- Morphology and solid state

- Surface characteristics

- Tendency for aggregation/agglomeration Early identification of CQAs helps manufacturers develop appropriate in-process controls [5].

Table 1: Key FDA Nanotechnology Guidance Documents

| Document Title | Focus Area | Issue Date | Status | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Products, Including Biological Products, that Contain Nanomaterials | Human drug products & biologics | April 2022 | Final | Development considerations for drug products where nanomaterials serve as active/inactive ingredients or carriers [10] |

| Further guidance documents listed on FDA's Nanotechnology Guidance webpage | Various FDA-regulated products | Varies | Final & Draft | Address use of nanotechnology/nanomaterials across product categories [19] |

Table 2: Technical Characterization Parameters for Nanomaterial-Containing Drug Products

| Parameter Category | Specific Attributes | Analytical Challenges | Impact on Product Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical Properties | Particle size/size distribution, surface charge, surface chemistry, morphology, solid state | Standard microscopy limited to >250 nm; requires specialized techniques | Affects biological behavior, stability, and performance [5] |

| Manufacturing Controls | Process sensitivity, scale-up effects, purification methods | Reproducibility challenges during manufacturing scale-up | Impacts consistency and quality of final product [5] |

| Stability Considerations | Size distribution changes, aggregation/agglomeration, morphological shifts | Requires specialized stability-indicating methods | Affects shelf life, storage conditions, and in vivo performance [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Nanomaterial Characterization

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Physicochemical Characterization

Objective: To fully characterize nanomaterials in drug products to establish Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) [5].

Methodology:

- Particle Size Analysis:

- Employ dynamic light scattering (DLS) for hydrodynamic diameter

- Use electron microscopy (SEM/TEM) for primary particle size and morphology

- Implement asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation (AF4) for complex mixtures

Surface Characterization:

- Determine zeta potential using electrophoretic light scattering

- Analyze surface chemistry through X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)

- Quantify surface functional groups using spectroscopic methods

Structural Analysis:

- Assess crystallinity using X-ray diffraction (XRD)

- Determine molecular weight distribution via gel permeation chromatography (GPC)

- Analyze elemental composition through inductively coupled plasma (ICP) techniques

Data Interpretation: Correlate physicochemical parameters with biological performance and stability profiles. Establish acceptance criteria for each CQA based on clinical relevance.

Protocol 2: Biological Safety Assessment

Objective: To evaluate potential biological interactions and safety concerns specific to nanomaterials [1] [5].

Methodology:

- In Vitro Toxicity Screening:

- Conduct cytotoxicity assays using multiple cell lines relevant to exposure routes

- Perform hemocompatibility testing for intravenous products

- Assess oxidative stress and inflammatory response markers

Biodistribution Studies:

- Use radiolabeling or fluorescent tagging to track nanomaterial distribution

- Quantify accumulation in target and non-target organs over time

- Evaluate clearance pathways and potential for long-term retention

Immunotoxicity Assessment:

- Analyze complement activation potential

- Assess effects on immune cell function and proliferation

- Evaluate potential for hypersensitivity reactions

Data Interpretation: Compare nanomaterial safety profile with conventional formulations. Identify nanomaterial-specific safety concerns that require additional monitoring.

Protocol 3: Manufacturing Control and Validation

Objective: To ensure consistent nanomaterial quality during manufacturing and scale-up [5].

Methodology:

- Process Parameter Optimization:

- Identify critical process parameters (CPPs) through design of experiments (DoE)

- Establish design space for nanomaterial synthesis and purification

- Define in-process controls for each manufacturing step

Scale-up Studies:

- Evaluate impact of scale on nanomaterial characteristics

- Identify potential critical quality attribute shifts during technology transfer

- Establish equivalence criteria between development and commercial scales

Purification and Isolation:

- Optimize purification methods to remove process impurities

- Establish controls for residual solvents and catalysts

- Validate cleaning procedures for equipment dedication

Data Interpretation: Demonstrate manufacturing process robustness and establish validated analytical methods for routine quality control.

Regulatory Pathway Decision Framework

Nanomaterial Characterization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Nanomaterial Research and Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipids | Form nanoliposomal structures for drug delivery | Doxil (doxorubicin) formulations | Purity critical for structure/function; must control oxidation [5] |

| Polymers | Create nanoparticle carriers for controlled release | Polymeric nanoparticles for gene delivery | Molecular weight distribution affects drug release kinetics [5] |

| Surface Modifiers | Modify nanomaterial surface properties | PEG coating for stealth properties | Surface density and conformation impact biological behavior [5] |

| Characterization Standards | Validate analytical methods | Size standards, reference materials | Essential for method qualification and comparability studies [5] |

| Stability Indicators | Monitor product degradation | Antioxidants, preservatives | Must not interfere with nanomaterial properties or performance [5] |

Developing and Submitting Your Nanotechnology Product for FDA Review

Premarket Review Requirements for Drugs, Biologics, and Devices

Technical Support Center: FAQs and Troubleshooting

This guide provides answers to frequently asked questions and troubleshooting advice for researchers and scientists navigating the premarket review requirements for drugs, biologics, and devices, with a specific focus on products involving nanotechnology.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the foundational regulatory standard for a Quality Management System (QMS) in medical device development? The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has updated its medical device current good manufacturing practice (CGMP) requirements by incorporating by reference the international standard ISO 13485:2016. This means that aligning your quality system with ISO 13485 is a central expectation for most premarket submissions for devices [20].

Q2: Does the FDA require special labeling for products using nanotechnology? Based on past assessments, FDA task forces have concluded that products using nanotechnology do not automatically require special labeling. This determination is made on a case-by-case basis, as the current science does not consistently show that nanomaterials pose a greater safety concern than their larger counterparts. However, all products must still meet existing safety substantiation requirements [21].

Q3: How is a "biologic" different from a "drug" in the context of premarket review? The key difference lies in the origin and complexity of the product. Biologics are derived from living organisms and are generally larger and more complex than chemically synthesized drugs. This distinction is critical because the pathway for demonstrating similarity to an existing product differs significantly, as seen with the biosimilar approval process for biologics versus the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway for generic drugs [22].

Q4: What is a major recent change intended to streamline the biosimilar approval process? In a significant update from October 2025, the FDA issued a draft guidance that may reduce the need for comparative clinical efficacy studies for certain biosimilars. If a developer can provide a highly sensitive comparative analytical assessment demonstrating biosimilarity, along with a pharmacokinetic similarity study and an immunogenicity assessment, it may be sufficient for approval. This can potentially shorten the development timeline by 1-3 years [22].

Q5: Where can I find the FDA's official guidances on premarket submissions? The FDA provides a centralized search page for all guidance documents on its website. You can search by keywords (e.g., "premarket," "nanotechnology") and filter results by product category (e.g., "Medical Devices," "Biologics"), issue date, and document status (draft or final) to find the most current information [4].

Troubleshooting Common Scenarios

Scenario 1: Uncertainty about QMS documentation for a premarket device submission.

- Problem: A sponsor is unsure what quality system information to include in a Premarket Approval (PMA) application for a new device incorporating nanomaterials.

- Solution: Consult the FDA's draft guidance, "Quality Management System Information for Certain Premarket Submission Reviews." This document outlines the expectations for QMS information in submissions once the updated rule aligning 21 CFR Part 820 with ISO 13485 takes effect. Ensure your QMS procedures and submitted documentation are compliant with the principles of ISO 13485:2016 [20].

Scenario 2: A clinical laboratory is unsure about the regulatory status of its Laboratory Developed Tests (LDTs).

- Problem: Following recent litigation, there is confusion over whether LDTs are regulated as medical devices.

- Solution: As of 2025, the status has reverted to the previous framework. A U.S. District Court vacated the FDA's rule that sought to extend its authority over LDTs, classifying them as "professional medical services" outside the scope of medical device regulation. Laboratories should maintain vigilance for any new legislative or regulatory actions from Congress or the FDA [23].

Scenario 3: Designing a clinical trial for a biosimilar product.

- Problem: A sponsor wants to avoid the high cost and long duration of a comparative clinical efficacy study for a biosimilar.

- Solution: Refer to the FDA's new draft guidance on biosimilars. Focus resources on developing a robust comparative analytical assessment that demonstrates the proposed biosimilar is highly similar to the reference product. If the product meets certain criteria (e.g., is well-characterized, and the relationship between its attributes and clinical efficacy is understood), you may be able to submit a justification to waive the comparative efficacy study, relying instead on pharmacokinetic and immunogenicity data [22].

The table below summarizes key quantitative information related to premarket pathways and regulatory actions.

Table 1: Key Regulatory and Development Metrics

| Metric | Data | Context / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Potential Biosimilar Development Time Saved | 1-3 years | Via updated FDA guidance waiving comparative clinical efficacy studies [22]. |

| Average Cost of Clinical Efficacy Study | ~$24 million | For biosimilar development [22]. |

| Approved Biosimilars (as of 2025) | 76 | Referencing a "small fraction of approved biologics" [22]. |

| ISO Standard for Device QMS | ISO 13485:2016 | Incorporated by reference in updated FDA QMSR [20]. |

Experimental Protocols for Regulatory Science

This section outlines generalized methodologies for key experiments often required in premarket submissions, particularly for novel products like those using nanomaterials.

Protocol 1: Comparative Analytical Assessment for a Biosimilar

1. Objective: To demonstrate through extensive structural and functional analysis that a proposed biosimilar product is highly similar to an FDA-licensed reference product, despite minor differences in clinically inactive components.

2. Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Reference Product: Multiple lots of the originator biologic product.

- Proposed Biosimilar: Multiple manufacturing lots of the product under development.

- Cell Lines: Clonal cell lines for production (e.g., CHO cells).

- Analytical Instruments: Mass spectrometers, chromatographs (HPLC, UPLC), capillary electrophoresis systems, circular dichroism spectrometers.

- Assay Kits: For evaluating biological activity (e.g., cell-based bioassays, binding ELISAs).

3. Methodology:

- Primary Structure Analysis: Use peptide mapping with LC-MS/MS to confirm amino acid sequence and post-translational modifications (e.g., glycosylation, oxidation).

- Higher-Order Structure Analysis: Employ techniques like Circular Dichroism (CD) and Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) to assess secondary and tertiary structure.

- Functional Assays:

- Conduct in vitro bioassays to measure the biological activity relative to the reference product. This often involves cell-based proliferation or signaling assays.

- Perform binding assays (e.g., Surface Plasmon Resonance) to characterize affinity for target receptors.

- Impurity and Stability Profile: Compare levels of product-related impurities (e.g., aggregates, fragments) and degradation profiles under stressed conditions (e.g., heat, light, pH) to the reference product.

- Data Analysis: Use statistical methods to establish equivalence ranges and demonstrate that any observed differences are within pre-defined, justified limits and are not clinically meaningful.

Protocol 2: Quality Management System (QMS) Audit for a Medical Device

1. Objective: To ensure a manufacturer's QMS complies with FDA regulations, which are harmonized with ISO 13485:2016, and is capable of consistently producing devices that meet specifications and regulatory requirements.

2. Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- QMS Documentation: Quality manual, documented procedures, standard operating procedures (SOPs).

- Records: Design history file (DHF), device master record (DMR), device history records (DHRs), management review records, internal audit reports.

- Traceability Tools: A system for tracking components, materials, and finished devices.

3. Methodology:

- Documentation Review: Audit the QMS documentation to verify it addresses all required elements of the quality system regulation (21 CFR 820 / ISO 13485), including management responsibility, resource management, product realization, and measurement, analysis, and improvement.

- Process Confirmation: Observe processes like design controls, purchasing controls, production and process controls, and corrective and preventive action (CAPA) to ensure they are implemented as documented.

- Record Sampling: Select a sample of DHRs to verify that devices were manufactured according to the DMR. Review CAPA records to ensure non-conformities are investigated, resolved, and effectiveness checks are performed.

- Management Interview: Interview top management to confirm their commitment to the quality policy and that quality objectives are established and reviewed.

- Reporting: Document all findings (conformities and non-conformities) in an audit report. Non-conformities require a root cause analysis and a corrective action plan.

Regulatory Pathway and Experimental Workflow Visualization

Premarket Review Logic Flow

Biosimilar Analytical Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Regulatory-Focused Experiments

| Item / Solution | Function in Premarket Development |

|---|---|

| ISO 13485:2016 Standard | The foundational framework for establishing a Quality Management System for medical devices, as recognized by the FDA [20]. |

| Reference Product | The licensed originator product (for biologics/drugs) or predicate device; serves as the benchmark for demonstrating comparability, similarity, or substantial equivalence [22]. |

| Clonal Cell Lines | Used in the production of biologics and biosimilars to ensure consistency and purity, a key factor in the updated biosimilar guidance [22]. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | A core analytical technique for characterizing the primary structure (amino acid sequence, post-translational modifications) of protein-based products [22]. |

| Cell-Based Bioassays | Functional assays used to measure the biological activity of a product (e.g., a biologic or biosimilar) and demonstrate it is equivalent to the reference product [22]. |

| Nanomaterial Characterization Tools | Instruments for measuring size, surface charge, and morphology (e.g., DLS, SEM, TEM) are critical for products using nanotechnology to understand their potential impact [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does the FDA define "nanomaterial" for regulatory purposes?

The FDA has not established a single rigid regulatory definition. However, the agency considers whether a material or end product is engineered to have at least one external dimension, or an internal or surface structure, in the nanoscale range (approximately 1 nm to 100 nm). Furthermore, the FDA also considers whether a material is engineered to exhibit properties or phenomena attributable to its dimension(s), even if these dimensions fall outside the nanoscale range, up to one micrometer (1,000 nm) [25] [5]. This flexible, case-specific approach allows the FDA to evaluate a diverse range of nanomaterials.

Q2: Are the safety standards for nanomaterials different from those for conventional materials?

No, the same standards of safety, efficacy, and quality apply to products containing nanomaterials as to all other regulated products [5] [2]. However, the pathway to meeting these standards may differ. The unique properties of nanomaterials, such as increased surface area and altered bioavailability, may necessitate additional or modified testing to provide sufficient evidence that the product meets the required safety and effectiveness standards for its intended use [1] [25].

Q3: What is the most critical step in the early development of a product containing nanomaterials?

Early consultation with the FDA is highly encouraged [1] [2]. The agency advises manufacturers to engage in pre-submission meetings to facilitate a mutual understanding of the specific scientific and regulatory issues for their nanotechnology product. This is crucial for clarifying the methodologies and data needed to meet regulatory obligations, especially given the product-specific nature of the FDA's assessment [1].

Q4: For which product types does the FDA require premarket review of nanomaterials?

The requirement for premarket review depends on the product category, not the presence of nanomaterials per se. The following table summarizes the premarket review status for major product categories [1]:

| Product Category | Premarket Review Required? | Governing Statute |

|---|---|---|

| New Drugs & Biologics | Yes (NDA, BLA) | FD&C Act § 505 |

| New Animal Drugs | Yes | FD&C Act |

| Food Additives & Color Additives | Yes | FD&C Act § 409 |

| Certain Medical Devices | Yes (PMA, 510(k)) | FD&C Act |

| Dietary Supplements (with certain new dietary ingredients) | Yes | FD&C Act |

| Cosmetics (except color additives) | No | FD&C Act |

| Most Dietary Supplements | No | FD&C Act |

Q5: If my cosmetic product contains a nanomaterial, what are my responsibilities?

Although cosmetics (except for color additives) are not subject to FDA premarket approval, manufacturers are legally responsible for ensuring their products are safe and properly labeled [25]. The cosmetic must not be adulterated or misbranded. For nanomaterials, this means you must substantiate the safety of the product through adequate testing, which may require special consideration of the nanomaterial's unique properties. The FDA encourages voluntary consultation and submission of safety substantiation data [1] [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent Results in Particle Size Distribution Analysis

Problem: Measurements of particle size and size distribution, a Critical Quality Attribute (CQA), show high variability between batches or during stability testing.

Solution:

- Validate Characterization Methods: Standard light microscopes cannot resolve objects smaller than ~250 nm [5]. Ensure you are using specialized techniques appropriate for the nanoscale, such as:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

- Electron Microscopy (SEM, TEM)

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

- Control Manufacturing Processes: Nanomaterials can be sensitive to process conditions and scale-up. Identify and tightly control Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) that impact particle size, such as mixing speed, temperature, and solvent addition rates [5].

- Conduct Stability Studies: Monitor for changes in particle size distribution over time as part of your stability protocol. Aggregation or agglomeration can be a sign of formulation instability [5].

Issue: Difficulty in Assessing Nanomaterial Toxicity Using Standard Tests

Problem: Traditional toxicology testing methods may not be fully applicable or may yield misleading results due to the distinctive physicochemical properties of nanomaterials.

Solution:

- Conduct Thorough Material Characterization: Before toxicological assessment, fully characterize the nanomaterial. Key properties include [25]:

- Size, size distribution, and aggregation state

- Morphology and shape

- Surface chemistry, charge, and area

- Chemical composition and purity

- Modify Testing Protocols: Traditional assays may need to be modified to account for nanomaterial-specific behaviors, such as interference with assay reagents or adsorption of biomolecules. Consider using dosimetry metrics relevant to the nanoscale (e.g., surface area) in addition to mass concentration [25].

- Investigate Toxicokinetics: Evaluate the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) profile of the nanomaterial, as its small size may alter its bioavailability and biodistribution compared to its larger-scale counterpart [25].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Framework for Safety Assessment of Nanomaterials in Cosmetics

This protocol outlines a general framework for assessing the safety of nanomaterials in cosmetic products, as recommended by the FDA [25].

1. Principle: The safety assessment should be sufficiently robust and flexible to account for the novel or altered properties of nanomaterials. It relies on thorough material characterization and toxicological evaluation, which may require modified or novel testing methods.

2. Methodology:

- Step 1: Physicochemical Characterization

- Determine particle size, size distribution, and dispersion state.

- Analyze morphology (shape, structure) using electron microscopy.

- Measure surface characteristics: zeta potential, surface chemistry, functional groups, and surface area.

- Determine chemical composition, including crystallinity and impurity profile.

- Step 2: Toxicological Assessment

- Uptake and Absorption: Assess dermal penetration and potential for systemic exposure using appropriate in vitro or ex vivo models (e.g., reconstructed human epidermis).

- Toxicity Testing:

- Conduct in vitro assays for cytotoxicity, phototoxicity, and genotoxicity.

- Perform in vivo studies for repeated dose toxicity, sensitization, and irritation as needed.

- Toxicokinetics: Investigate the distribution, metabolism, and excretion of the nanomaterial if systemic exposure is anticipated.

- Step 3: Safety Substantiation

- Integrate all characterization and toxicology data.

- Perform a risk assessment based on the intended use and exposure levels.

- Establish the final safety conclusion for the finished product.

Protocol 2: Identifying Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) for Nanomaterial Drug Products

This protocol describes the process for identifying CQAs for a nanomaterial-based drug product, which is essential for developing appropriate controls [5].

1. Principle: CQAs are physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological properties that must be within an appropriate limit, range, or distribution to ensure the desired product quality, safety, and efficacy. For nanomaterials, these are often linked to their physical nanostructure.

2. Methodology:

- Step 1: Link Material Properties to Clinical Performance

- Bridge changes in nanomaterial properties (e.g., size, surface charge) to desired clinical outcomes (e.g., targeting, drug release profile, reduced toxicity).

- Step 2: Identify Potential CQAs

- Based on the link to performance, identify properties that are likely critical. For nanomaterials, this often includes:

- Particle size and polydispersity index (PDI)

- Particle surface charge (Zeta Potential)

- Drug loading and encapsulation efficiency

- In vitro drug release profile

- Morphology and structural integrity

- Based on the link to performance, identify properties that are likely critical. For nanomaterials, this often includes:

- Step 3: Develop and Implement Controls

- Develop in-process controls and analytical methods to monitor these CQAs during manufacturing.

- Include these CQAs in stability-testing protocols to monitor changes over the product's shelf life.

Quantitative Data and Standards

The following table summarizes key physicochemical parameters that often require monitoring and typical analytical techniques used, as referenced in FDA guidance documents [25] [5].

| Parameter | Significance / Impact | Recommended Analytical Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Size & Distribution | Affects biodistribution, targeting, clearance, and toxicity profile. | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM), Analytical Ultracentrifugation |

| Zeta Potential | Indicates colloidal stability; influences cellular uptake and interaction with biological components. | Electrophoretic Light Scattering |

| Surface Area | Increased area can enhance reactivity, dissolution, and biological activity. | Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) Analysis |

| Surface Chemistry | Determines biological identity (protein corona), targeting, and safety. | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) |

| Crystallinity | Can impact chemical stability, dissolution rate, and bioavailability. | X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) |

| Drug Release Kinetics | Critical for efficacy; must be demonstrated in a physiologically relevant medium. | Dialysis, Franz Diffusion Cell, USP Apparatus |

Regulatory Pathway Diagram

Safety Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Standard Reference Materials | Certified materials with known properties (e.g., size, surface area) used for calibration and validation of analytical instruments. |

| Cell Culture Models | In vitro systems (e.g., reconstructed human epidermis, Caco-2 cells) used for initial screening of cytotoxicity, absorption, and irritation. |

| Lipids & Polymers | Building blocks for engineered nanomaterials like liposomes and polymeric nanoparticles, used as drug delivery vehicles or functional excipients. |

| Surface Modifiers | PEG, peptides, or other ligands used to functionalize the surface of nanomaterials to improve stability, targeting, or reduce immunogenicity. |

| Stability Testing Buffers | Simulated biological fluids (e.g., simulated gastric fluid, plasma) used to assess the stability and drug release profile of the nanomaterial under physiological conditions. |

| Analytical Standards | High-purity nanomaterials used as benchmarks for comparing properties and performance between batches during development and quality control. |

The Critical Importance of Early FDA Consultation in the Development Process

For researchers and scientists developing nanotechnology-enabled products, engaging with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) early in the development process is a critical strategic step. The FDA regulates nanotechnology products under existing statutory authorities, employing a product-focused, science-based regulatory policy that varies according to the specific legal standards applicable to each product type [1]. Nanomaterials can exhibit different chemical, physical, or biological properties compared to their larger-scale counterparts, which may raise important questions about product safety, effectiveness, performance, quality, or public health impact [6] [2]. The FDA does not categorically judge all products containing nanomaterials as intrinsically benign or harmful, but rather evaluates them on a case-by-case basis according to their specific characteristics and intended use [1]. This article provides a technical guide to facilitate effective regulatory navigation for nanotechnology products, emphasizing why early consultation is essential for efficient development.

Determining When Your Product Involves Nanotechnology

FDA's Points to Consider

The FDA has issued guidance outlining two key points to consider when determining whether an FDA-regulated product involves the application of nanotechnology. These points serve as an initial screening tool that researchers should apply during early development phases [6].

| Point to Consider | Description | Technical Scope |

|---|---|---|

| Point 1 | Whether a material or end product is engineered to have at least one external dimension, or an internal or surface structure, in the nanoscale range. | Approximately 1 nm to 100 nm [6] |

| Point 2 | Whether a material or end product is engineered to exhibit properties or phenomena attributable to its dimension(s), even if these dimensions fall outside the nanoscale range. | Up to one micrometer (1,000 nm) [6] |

Key Terminology and Concepts

- Engineered Materials: The FDA specifically focuses on materials that have been "deliberately manipulated" to produce specific properties, distinguishing them from materials that naturally exist at the nanoscale or are incidentally present in conventionally-manufactured products [6].

- Dimension-Dependent Properties: Properties or phenomena (e.g., increased structural integrity, altered chemical or biological activity) that are attributable to a material's dimension(s), even outside the traditional 1-100 nm range [6].

Troubleshooting Common Nanotechnology Development Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our nanoparticle-based drug delivery system has dimensions between 100-200 nm but exhibits properties not seen in larger particles. Does this require special FDA consideration?

A: Yes. According to FDA guidance, materials engineered to exhibit dimension-dependent properties even outside the traditional 1-100 nm range (up to 1,000 nm) may merit particular examination. You should evaluate whether these new properties affect safety, effectiveness, or public health impact, and consult with the FDA [6].

Q2: We're developing a cosmetic product containing nanomaterials. What are our regulatory obligations?

A: While cosmetics (except color additives) are not subject to mandatory premarket review, you remain responsible for ensuring your product meets all applicable safety standards. The FDA encourages voluntary consultation before marketing and recommends conducting a robust safety assessment that addresses the unique physicochemical properties and potential toxicological implications of nanomaterials [1].

Q3: Our company wants to use a previously approved drug substance in a new nanoformulation. What regulatory pathway applies?

A: A new drug application would typically be required because the nanoformulation may have different safety, effectiveness, or bioavailability profiles compared to the conventionally-manufactured product. You must submit data demonstrating the safety and effectiveness of the new formulation, paying particular attention to how the nanoscale properties may affect its behavior [1].

Q4: What specific technical data should we prepare for an early FDA consultation regarding our nanotechnology product?

A: You should be prepared to discuss:

- Comprehensive physicochemical characterization of the nanomaterial

- Identification and control of critical quality attributes

- Demonstration of manufacturing process control and consistency

- Preliminary safety and toxicology data specific to the nanomaterial properties

- Assessment of potential changes in bioavailability, pharmacokinetics, or biological effects compared to non-nano counterparts [1]

Experimental Protocols for Nanotechnology Product Characterization

Key Methodologies for Regulatory Submissions

Protocol 1: Physicochemical Characterization of Nanomaterials

Purpose: To comprehensively characterize nanomaterials for regulatory submissions, addressing the FDA's emphasis on understanding unique properties that may impact product safety or performance [6].

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified nanomaterial sample

- Appropriate dispersion media (e.g., PBS, cell culture medium)

- Reference standards (when available)

- Grids for electron microscopy (as applicable)

Procedure:

- Size and Size Distribution: Perform dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements in triplicate using appropriate dispersion media reflective of the product's use conditions.

- Surface Charge: Determine zeta potential using electrophoretic light scattering in relevant physiological buffers.

- Morphology: Characterize particle morphology using transmission or scanning electron microscopy (TEM/SEM).

- Surface Chemistry: Analyze surface functional groups using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) or Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR).

- Crystallinity: Assess crystalline structure using X-ray diffraction (XRD).

- Surface Area: Determine specific surface area using Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method.

Data Analysis: Document mean particle size, polydispersity index, zeta potential, and other relevant parameters. Compare multiple batches to establish consistency.

Troubleshooting Tip: If aggregation occurs during characterization, optimize dispersion protocols while maintaining physiological relevance.

Protocol 2: Assessment of Nanomaterial Stability

Purpose: To evaluate the stability of nanomaterials under conditions relevant to manufacturing, storage, and use, as stability changes may alter safety or performance profiles [1].

Materials and Reagents:

- Nanomaterial formulation

- Appropriate storage containers

- Analytical instruments for characterization (as above)

Procedure: