Nanoparticle Targeting Efficiency in Cancer Therapy: Mechanisms, Optimization, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of nanoparticle targeting strategies for cancer therapy, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Nanoparticle Targeting Efficiency in Cancer Therapy: Mechanisms, Optimization, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of nanoparticle targeting strategies for cancer therapy, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of passive and active targeting, including the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect and ligand-receptor interactions. The review delves into advanced methodological approaches such as stimuli-responsive nanoplatforms and receptor-mediated targeting, while also addressing critical challenges like multidrug resistance, the protein corona effect, and physiological barriers. A comparative evaluation of targeting efficacy, supported by in vitro and in vivo data, is presented to validate different strategies. The synthesis of current knowledge aims to guide the rational design of next-generation nanotherapeutics for improved clinical outcomes.

Fundamental Principles of Nanoparticle Tumor Targeting

The Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect represents a foundational principle in cancer nanomedicine, first described by Matsumura and Maeda in 1986 [1]. This pathophysiological phenomenon enables the passive targeting of macromolecular drugs and nanocarriers to solid tumors, forming the basis for numerous therapeutic strategies in oncology [2] [1]. The EPR effect exploits the unique anatomical and physiological abnormalities of tumor vasculature, characterized by leaky blood vessels with enlarged inter-endothelial gaps (100-780 nm) and impaired lymphatic drainage systems [2] [3]. These pathological features allow nanoscale particles (typically 10-100 nm) to extravasate from the bloodstream into tumor tissue while promoting their prolonged retention within the tumor interstitium [4] [1].

The clinical significance of the EPR effect is substantial, underpinning at least 15 clinically approved nanomedicines including Doxil and Apealea [1]. By leveraging this passive targeting mechanism, nanocarriers can achieve higher drug concentrations at tumor sites while reducing systemic exposure, potentially minimizing off-target toxicity and improving therapeutic indices [4] [3]. However, the heterogeneity of the EPR effect across different tumor types, disease stages, and individual patients presents significant challenges for clinical translation, prompting researchers to develop innovative strategies to enhance and complement this natural targeting mechanism [5] [2] [1].

Pathophysiological Basis of the EPR Effect

Tumor Vasculature Abnormalities

The structural foundation of the EPR effect lies in the aberrant vasculature of solid tumors. Unlike normal tissues with organized angiogenesis, tumors exhibit rapid, dysregulated blood vessel formation driven by hypoxia and cancer cell-derived signals [2]. This results in structurally and functionally compromised vasculature with discontinuous endothelium, incomplete basement membranes, and abnormal pericyte coverage [1]. The endothelial gaps in tumor vessels typically range from 100-780 nm, significantly larger than the 5-10 nm fenestrations found in normal continuous capillaries, thereby facilitating the extravasation of nanomedicines [2] [3].

Several molecular mediators contribute to this hyperpermeability, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), prostaglandins, bradykinin, nitric oxide, and various proteases [2]. These factors not only promote angiogenesis but also actively increase vascular permeability by inducing endothelial cell contraction and disrupting cell-cell junctions [5]. The resulting "leaky" vasculature enables the passive accumulation of nanoparticles and macromolecular therapeutics in tumor tissues, representing the "enhanced permeability" component of the EPR effect [1].

Impaired Lymphatic Drainage and Retention Mechanisms

The "retention" component of the EPR effect stems from deficient lymphatic function within tumor tissues [1]. Solid tumors typically exhibit compressed or non-functional lymphatic vessels due to rapid cancer cell proliferation and increased interstitial pressure [2] [3]. This impaired lymphatic clearance, combined with the characteristic dense extracellular matrix (ECM) of tumors, prevents the efficient removal of extravasated macromolecules and nanoparticles [2] [1].

The tumor microenvironment further promotes retention through multiple mechanisms. High collagen content, elevated hyaluronan levels, and increased stromal cell density create a physical barrier that traps nanocarriers within the tumor interstitium [2]. Additionally, elevated interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) within tumor cores, resulting from vascular leakage and poor lymphatic drainage, can approach that of the microvasculature, potentially hindering convective transport while still permitting diffusion-based nanoparticle distribution [2] [3]. These combined factors enable the prolonged retention of nanomedicines, potentially increasing their therapeutic efficacy against cancer cells [1].

Table 1: Key Pathophysiological Features Underlying the EPR Effect

| Feature | Description | Impact on EPR |

|---|---|---|

| Vascular Hyperpermeability | Discontinuous endothelium with 100-780 nm gaps | Enables extravasation of nanoparticles and macromolecules |

| Aberrant Angiogenesis | Rapid, disorganized blood vessel formation | Creates structurally abnormal vasculature prone to leakage |

| Vascular Mediators | VEGF, prostaglandins, bradykinin, nitric oxide | Actively increase vascular permeability through endothelial cell contraction |

| Deficient Lymphatic System | Compressed or non-functional lymphatic vessels | Reduces clearance of extravasated particles |

| Dense Extracellular Matrix | High collagen, hyaluronan, and stromal cell density | Traps nanoparticles within tumor interstitium |

| Elevated Interstitial Fluid Pressure | Increased pressure from vascular leakage and poor drainage | May hinder convective transport but permits diffusion |

Critical Analysis of EPR Limitations and Heterogeneity

Inter- and Intra-tumor Heterogeneity

The EPR effect demonstrates significant variability that substantially impacts its therapeutic reliability [2] [1]. This heterogeneity manifests at multiple levels, creating substantial challenges for clinical translation of EPR-dependent nanomedicines. Different tumor types exhibit markedly different EPR characteristics, with pancreatic cancers typically demonstrating less leaky vasculature compared to other solid tumors [6]. Furthermore, heterogeneity exists within individual tumors, where well-perfused peripheral regions may show robust EPR effects while hypoxic central regions exhibit limited nanoparticle accumulation due to compressed vasculature and elevated interstitial fluid pressure [2] [3].

Temporal evolution of the EPR effect presents additional complications, as early-stage tumors often possess more organized vasculature with less pronounced EPR characteristics compared to advanced, late-stage tumors [6]. This temporal variability is further complicated by species-dependent differences, with the EPR effect being more consistently observed in murine tumor models than in human patients, partially explaining the frequent discrepancy between preclinical success and clinical outcomes [6] [1]. These multifaceted heterogeneity issues necessitate careful patient stratification and the development of complementary strategies to enhance EPR-mediated drug delivery [5] [1].

Physiological and Biological Barriers

Several physiological barriers within the tumor microenvironment limit the effectiveness of the EPR effect. Elevated interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) resulting from vascular leakage and impaired lymphatic function can create pressure gradients that hinder nanoparticle penetration from vessels into the tumor interstitium [2] [3]. This elevated IFP is particularly pronounced in larger tumors, potentially explaining the limited penetration of nanomedicines into tumor cores [3].

The dense extracellular matrix (ECM) of tumors, characterized by high collagen content, increased stromal cellularity, and abnormal ECM cross-linking, creates significant physical barriers to nanoparticle distribution [2]. This dense stroma not limits diffusion but also sequesters various growth factors and cytokines that further modulate tumor pathophysiology [2] [1]. Additionally, cellular components including tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and other phagocytic cells can actively take up and sequester nanoparticles, potentially diverting them from their intended targets [5] [7]. These biological barriers collectively contribute to the limited penetration and heterogeneous distribution of nanomedicines within tumors, even when extravasation occurs efficiently [2] [1].

Diagram 1: Key Limitations Affecting EPR Efficacy

Quantitative Assessment of EPR Performance

Nanoparticle Delivery Efficiency Metrics

The overall delivery efficiency of nanoparticles to tumors via the EPR effect remains surprisingly low, with quantitative studies indicating that only approximately 0.7% of the injected nanoparticle dose typically accumulates in solid tumors [8]. This low accumulation efficiency represents a significant challenge for clinical translation of EPR-based therapies. The distribution of nanoparticles within tumors follows heterogeneous patterns, with peripheral regions often receiving higher nanoparticle concentrations compared to hypoxic central regions where therapeutic need may be greatest [2] [3].

Multiple factors influence this delivery efficiency, including nanoparticle physicochemical properties, tumor type, vascular density, and specific pathophysiological characteristics of individual tumors [2] [8]. The mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), particularly macrophages in the liver and spleen, represents the primary clearance pathway for systemically administered nanoparticles, significantly reducing their circulation half-life and availability for tumor accumulation [8]. Renal clearance further depletes smaller nanoparticles (<10 nm), while opsonization and immune recognition accelerate removal from circulation, collectively contributing to the modest tumor accumulation percentages observed across numerous studies [4] [8].

Impact of Nanoparticle Design Parameters

Nanoparticle physicochemical properties significantly influence their performance in EPR-mediated tumor targeting. Size represents a critical parameter, with optimal nanoparticle diameters typically falling between 10-100 nm [4]. Particles smaller than 10 nm undergo rapid renal clearance, while those exceeding 100 nm experience increased recognition and clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system [4] [8]. Surface characteristics, particularly hydrophilicity and charge, substantially impact circulation half-life, with PEGylation (polyethylene glycol coating) demonstrating proven benefits in reducing opsonization and extending circulation time [4] [8].

Shape and rigidity represent additional design considerations that influence margination, vascular transport, and extravasation potential [8]. The nanoparticle material composition (lipidic, polymeric, or inorganic) further affects drug loading capacity, release kinetics, and biocompatibility [9] [4]. These design parameters must be carefully optimized to maximize EPR-mediated tumor accumulation while minimizing off-target distribution and clearance [4] [8].

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Nanoparticle Parameters Influencing EPR Efficacy

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Impact on EPR Efficiency | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | 10-100 nm | <10 nm: Renal clearance>100 nm: MPS clearance | Preclinical models show 20-100 nm particles have longest circulation and highest tumor accumulation [4] [8] |

| Surface Charge | Neutral to slightly negative | Positive charge: Rapid clearanceNegative charge: Prolonged circulation | Neutral/slightly negative particles demonstrate 2-3× longer half-life than highly charged particles [4] [7] |

| Surface Modification | PEGylation | Reduces opsonization, extends circulation | PEGylated liposomes show 40-60% longer circulation half-life vs. non-PEGylated [4] [8] |

| Drug Loading Capacity | >5% w/w | Higher payload improves therapeutic efficacy | Polymeric NPs achieve 5-20% loading; dendrimers can reach 30%+ [9] [4] |

| Tumor Accumulation | ~0.7% ID/g | Only fraction reaches tumor tissue | Quantitative biodistribution studies across multiple nanoformulations [8] |

Strategies to Enhance EPR-Mediated Drug Delivery

Pharmacological and Physical Priming Approaches

Several strategies have been developed to enhance the EPR effect through pharmacological or physical modulation of the tumor microenvironment. Pharmacological approaches include using angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors to normalize blood pressure and improve tumor perfusion, or administering vascular mediators such as nitric oxide donors, prostaglandins, or bradykinin analogs to actively increase vascular permeability [5] [2]. These pharmacological primers can be administered prior to nanomedicine treatment to create a more favorable environment for nanoparticle extravasation and distribution [5].

Physical priming methods utilize external energy sources to locally enhance vascular permeability and nanoparticle delivery. These include mild hyperthermia, which can expand endothelial gaps and improve nanoparticle extravasation [6]; ultrasound, particularly in combination with microbubbles (sonoporation) that mechanically disrupt vessel walls [5]; and radiation therapy, which can modulate vascular function and increase permeability in irradiated fields [5]. These physical approaches offer spatial and temporal control over EPR enhancement, potentially minimizing systemic effects while improving local drug delivery [5] [6].

Advanced Nanocarrier Design Strategies

Sophisticated nanocarrier engineering represents another promising approach to enhance EPR-mediated drug delivery. Multi-stage delivery systems incorporate size-shrinking capabilities or charge-reversal mechanisms that optimize different aspects of the delivery process [2] [1]. For example, larger carriers (100-200 nm) may demonstrate optimal vascular transport and initial extravasation, then release smaller nanoparticles (10-20 nm) that penetrate deeper into tumor tissue [2].

Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers that react to tumor-specific signals (pH, enzymes, redox status) or external triggers (light, magnetic fields) offer additional targeting precision [9] [1]. These "smart" nanoparticles can maintain stable circulation while activating their targeting or release mechanisms specifically within the tumor microenvironment [9]. Additionally, biomimetic approaches utilizing cell membrane coatings from platelets, leukocytes, or cancer cells themselves can exploit natural homing mechanisms to improve tumor accumulation while evading immune recognition [1]. These advanced design strategies aim to overcome biological barriers while leveraging the fundamental EPR effect for improved therapeutic outcomes [9] [1].

Diagram 2: EPR Enhancement Strategies

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vivo and Intravital Imaging Techniques

The evaluation of EPR effect efficiency relies heavily on advanced imaging methodologies that enable real-time visualization of nanoparticle distribution and tumor accumulation. Intravital microscopy (IVM) represents a powerful technique for directly observing nanoparticle extravasation, distribution, and retention in living animal models [10]. This approach provides dynamic, high-resolution information about the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of nanoparticle delivery, allowing researchers to identify specific vascular and stromal barriers that limit treatment efficacy [10].

Complementary techniques include fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) and Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), which can provide information about nanoparticle integrity and drug release kinetics within tumor tissues [10]. These advanced imaging methods have revealed critical insights into EPR heterogeneity, demonstrating how physiological factors including vascular density, perfusion efficiency, and interstitial pressure collectively influence nanoparticle distribution patterns [10] [8]. The experimental data generated through these techniques provides essential validation for EPR-based targeting strategies and informs the rational design of improved nanocarriers [10].

Standardized Evaluation Protocols

Robust assessment of EPR-mediated drug delivery requires standardized protocols for quantifying tumor accumulation and distribution. A typical experimental workflow begins with nanoparticle characterization to determine size distribution, surface charge, drug loading efficiency, and stability in physiological conditions [7]. Following intravenous administration in tumor-bearing models, researchers collect time-point samples to determine pharmacokinetic parameters including circulation half-life, volume of distribution, and clearance rates [4] [7].

Biodistribution studies quantify nanoparticle accumulation in tumors versus major organs (liver, spleen, kidneys, heart, lungs) using techniques including fluorescence imaging, radiolabeling, or mass spectrometry [7]. These studies typically express results as percentage injected dose per gram of tissue (% ID/g), allowing direct comparison between different nanocarrier formulations [8] [7]. Additional analyses may include histological assessment of nanoparticle distribution within tumor sections, penetration depth measurements, and correlation with therapeutic efficacy endpoints [10] [7]. These standardized protocols enable meaningful comparisons between different EPR-enhancement strategies and facilitate translation from preclinical models to clinical applications [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for EPR Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for EPR Effect Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanocarrier Platforms | PEGylated liposomes, PLGA nanoparticles, Gold nanorods, Dendrimers | Fundamental EPR effect studies; drug delivery optimization | Size control, surface modification capacity, drug loading efficiency [9] [4] |

| Imaging Agents | Fluorescent dyes (DiR, Cy5.5), Radiolabels (⁹⁹ᵐTc, ⁶⁴Cu), Contrast agents (IONPs) | Biodistribution studies; pharmacokinetic analysis; tumor accumulation quantification | Signal sensitivity, stability, compatibility with detection systems [10] [7] |

| Vascular Permeability Modulators | Nitric oxide donors, VEGF, Bradykinin analogs, ACE inhibitors | EPR enhancement studies; pharmacological priming approaches | Dosing optimization, temporal control, specificity for tumor vasculature [5] [2] |

| Tumor Model Systems | Subcutaneous xenografts, Orthotopic models, Genetically engineered models, Patient-derived xenografts | EPR heterogeneity assessment; translational relevance | Vascular characteristics, stromal composition, clinical relevance [10] [8] |

| Analytical Tools | HPLC/MS systems, Gamma counters, Fluorescence imaging systems, Histopathology platforms | Quantitative biodistribution; spatial distribution analysis | Sensitivity, quantification accuracy, spatial resolution [10] [7] |

The EPR effect remains a fundamental principle in cancer nanomedicine, providing the physiological basis for passive tumor targeting of nanotherapeutic agents. While substantial evidence supports its existence and utility, significant challenges persist due to the heterogeneity of the effect across different tumors and individual patients [5] [1]. The future of EPR-based drug delivery lies in developing personalized approaches that account for this heterogeneity through patient stratification and treatment customization [5] [1].

Emerging strategies focus on combining EPR-mediated passive targeting with active targeting mechanisms, physical enhancement methods, and sophisticated nanocarrier designs that respond to specific tumor microenvironment cues [5] [9] [1]. The integration of artificial intelligence and computational modeling approaches shows particular promise for optimizing nanoparticle design parameters and predicting EPR efficiency in individual patients [8] [1]. Additionally, advanced imaging techniques and biomarker development may enable better patient selection for EPR-based therapies, potentially identifying those most likely to benefit from nanomedicine approaches [5] [10].

As the field progresses, the successful clinical translation of EPR-based nanomedicines will likely require multimodal strategies that address the complex biological barriers of solid tumors while leveraging the fundamental principles of enhanced permeability and retention [2] [1]. Through continued refinement of nanocarrier design, enhancement techniques, and patient selection methods, the EPR effect will remain a cornerstone of targeted cancer therapy, enabling more effective and less toxic treatment options for cancer patients [5] [1].

Active targeting represents a sophisticated strategy in nanomedicine designed to enhance the specificity of therapeutic agents for diseased cells, thereby maximizing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects. This mechanism relies on the deliberate engineering of nanocarriers with surface-bound ligands that recognize and bind to specific receptors overexpressed on target cells [3]. Contrary to the common misconception that these ligands confer a "homing" ability, active targeting functions not by attracting nanoparticles from a distance but by significantly improving their retention and uptake at the target site following passive accumulation, a process fundamentally governed by short-range chemical forces [11]. The success of this approach is a delicate balance of multiple factors, including target receptor accessibility, ligand-receptor binding kinetics, and the physicochemical properties of the nanoparticle itself [11]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of active targeting strategies, focusing on the core principles of ligand-receptor interactions, the quantitative aspects governing these interactions, and the experimental methodologies used to evaluate their efficiency in the context of cancer therapy.

Fundamental Principles of Ligand-Receptor Interactions

The efficacy of actively targeted nanoparticles is not a simple function of ligand presence; it is governed by a two-step process that requires both successful contact and subsequent molecular engagement.

A Two-Step Mechanism: Contact and Retention

The process of active targeting can be broken down into two sequential, critical steps:

- Step 1: Contact: The nanoparticle must first come into close physical proximity with the target cell. The accessibility of the target cell is a primary determinant of success. For example, vascular endothelial cells are highly accessible to intravenously administered nanoparticles, whereas reaching extravascular tumor cells requires first crossing the vascular endothelium, a significant barrier that often limits delivery to a small fraction (~1%) of the injected dose [11].

- Step 2: Retention and Capture: Once contact is made, the conjugated ligands on the nanoparticle surface can engage with their cognate cell-surface receptors. This specific binding event facilitates the retention of the nanoparticle at the target site, increasing the likelihood of cellular internalization and thus, drug delivery [11]. This step is not a long-range "magnetic" pull but a short-range interaction mediated by hydrogen bonds and electrostatic forces that act over distances of merely 0.3–0.5 nm [11].

The Critical Role of Ligand Density and Avidity

The number of ligands on a nanoparticle's surface—its ligand density—is a crucial design parameter that directly impacts avidity (the cumulative strength of multiple simultaneous interactions) and cellular selectivity. Interestingly, "more" does not always mean "better." While engineered nanoparticles are typically coated with a high density of ligands, nature provides an optimized model in viruses, which achieve high target cell avidity and selectivity with a relatively low number of receptor-binding spikes [12].

Experimental studies using polymeric nanoparticles functionalized with an angiotensin II receptor antagonist revealed that only a fraction of the surface ligands (approximately 18%) are actually involved in specific binding to target cells [12]. This suggests that a strategic optimization of ligand number, rather than simple maximization, is key to developing nanoparticles with high efficiency and specificity, mirroring the evolutionary refinement seen in viruses [12].

Quantitative Comparison of Targeting Ligands and Strategies

The selection of a targeting ligand is a fundamental decision that influences the specificity, efficiency, and overall success of a nanocarrier system. The table below provides a comparative overview of commonly used ligand classes.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Targeting Ligands Used in Active Targeting

| Ligand Class | Example Target Receptor(s) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies/Aptamers | Various tumor-associated antigens | High specificity and binding affinity [3] | Large size may hinder penetration; potential immunogenicity [13] |

| Peptides | Integrins (e.g., αvβ3), Insulin Receptor | Good penetration; can be designed for allosteric sites [13] | Susceptible to proteolytic degradation; moderate affinity |

| Small Molecules | Folate receptor, Carbohydrate receptors | Low immunogenicity; favorable pharmacokinetics [3] | Limited number of well-characterized targets |

| Allosteric Peptides | Transmembrane Domains (TMDs) of receptors (e.g., IR) | Avoids competition from endogenous ligands; overcomes target loss from extracellular domain shedding [13] | Novel approach; requires extensive validation |

Emerging strategies are addressing the limitations of traditional orthosteric targeting. For instance, allosteric targeted drug delivery utilizes peptide ligands designed to bind specifically to the transmembrane domains (TMDs) of receptors, such as the insulin receptor (IR) or integrin αvβ3, rather than their extracellular domains [13]. This approach offers distinct advantages:

- Avoids Competitive Interference: It is not competitively inhibited by endogenous ligands like insulin, a common issue for ligands targeting the extracellular domain of the IR [13].

- Overcomes Target Loss: It remains effective even when the extracellular domain of a receptor is shed or mutated, a phenomenon that can render conventional targeting moieties ineffective [13].

- Plug-and-Play Simplicity: These lipophilic peptides can be spontaneously embedded into the phospholipid layers of lipid-based carriers (e.g., liposomes, lipid nanoparticles) without complex chemical conjugation [13].

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Ligand-Receptor Binding Parameters

| Targeting Strategy | Ligand/Receptor Pair | Measured Binding Parameter | Value | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthosteric Targeting | Losartan (EXP3174) / AT1R | Optimal Ligand Density | 29 ligands/100 nm² (total); 5.3 ligands/100 nm² (binding) [12] | ICP-MS, Flow Cytometry |

| Allosteric Targeting | ITP Peptide / IR TMD | Dissociation Constant (KD) | 2.10 × 10⁻⁷ M [13] | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) |

| Allosteric Targeting | ITP Peptide / IR TMD | Predicted Binding Free Energy | -43.59 kcal/mol [13] | MM/GBSA Molecular Modeling |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Targeting Efficiency

Robust experimental protocols are essential for quantifying the success of an active targeting strategy. The following sections detail key methodologies cited in recent literature.

Quantifying Ligand-Receptor Interactions on Cell Surfaces

A groundbreaking experimental approach was used to determine the exact number of ligands per nanoparticle involved in binding to target cells [12].

- Nanoparticle Model: Core-shell nanoparticles composed of PLGA and a PLA-PEG block copolymer, functionalized with EXP3174 (an AT1R antagonist) at a 25% surface density.

- Key Reagent: Selenium-tagged nanoparticles. Elemental selenium was embedded in the nanoparticle core to serve as a tag for highly sensitive quantification via Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) [12].

- Experimental Workflow:

- Incubate nanoparticles with AT1R-expressing rat mesangial cells.

- Use EXP3174 to saturate 50% of the cell surface receptors, ensuring the applied nanoparticle concentration equals its equilibrium inhibition constant (Ki).

- Thoroughly wash cells to remove unbound nanoparticles.

- Quantify cell-associated nanoparticles by measuring the selenium signal via ICP-MS.

- Calculate the average number of binding ligands per nanoparticle using a defined formula that considers the number of target receptors and the number of nanoparticles attached to the cell membrane [12].

Validating Allosteric Targeting Mechanisms

To confirm that a novel peptide (ITP) binds to the insulin receptor's transmembrane domain in an allosteric (non-competitive) manner, researchers employed the following protocol [13]:

- Cell Model: Primary brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs), which naturally express the insulin receptor.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Pre-incubate BMECs with either:

- The natural ligand, insulin (which binds the extracellular orthosteric site).

- The designed ITP peptide (targeting the TMD).

- A control scrambled peptide.

- Treat the pre-incubated cells with fluorescently labelled (FITC) insulin or fluorescently labelled ITP.

- Measure cellular uptake of the fluorescent compounds using flow cytometry.

- Pre-incubate BMECs with either:

- Key Outcome: Pre-incubation with insulin competitively inhibited the uptake of FITC-insulin but did not inhibit the uptake of FITC-ITP. Conversely, pre-incubation with ITP did not inhibit FITC-insulin uptake. This mutual non-interference conclusively demonstrated that ITP and insulin bind to distinct, non-competitive sites on the IR, validating the allosteric mechanism [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents and their functions as derived from the experimental methodologies discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Active Targeting Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA/PLA-PEG Copolymers | Forms biodegradable, biocompatible core-shell nanoparticles that can be functionalized with ligands [12]. | Model nanoparticle system for studying ligand density [12]. |

| Selenium Tag | An elemental tag incorporated into nanoparticles for ultra-sensitive quantification via ICP-MS [12]. | Precisely measuring the number of nanoparticles bound to cells [12]. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | A biosensor technique used to characterize biomolecular interactions in real-time without labels. | Measuring the dissociation constant (KD) between a peptide ligand and its target receptor [13]. |

| Allosteric Peptide Binders (e.g., ITP) | Peptides designed to bind the transmembrane domain of receptors, avoiding orthosteric competition [13]. | Enabling targeted drug delivery to the brain without interference from endogenous insulin [13]. |

| Fluorescent Probes (e.g., FITC, CY-5) | Dyes used to label ligands, drugs, or nanoparticles for visualization and quantification. | Tracking cellular uptake via flow cytometry or confocal microscopy [13]. |

Conceptual Framework and Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and mechanisms described in this guide.

Diagram 1: Two-Step Mechanism of Active Targeting

This diagram visualizes the fundamental process by which ligand-functionalized nanoparticles achieve target site retention.

Diagram 2: Orthosteric vs. Allosteric Targeting Strategy

This diagram contrasts the traditional orthosteric targeting approach with the novel allosteric strategy that avoids competitive inhibition.

Active targeting through ligand-receptor interactions has moved beyond the simple concept of attaching a ligand to a nanoparticle. The field is evolving towards a more nuanced and sophisticated understanding, emphasizing the quantitative optimization of ligand density, the strategic selection of highly accessible cellular targets, and the innovative development of allosteric targeting strategies that circumvent biological limitations. The experimental data and comparative analysis presented in this guide underscore that successful targeting is a kinetic competition, where enhancing the rate of accumulation and retention at the desired site is paramount. As the toolkit of ligands and nanocarriers expands, and with the aid of advanced quantitative experimental protocols, the rational design of next-generation targeted nanotherapies continues to hold immense promise for improving the precision and efficacy of cancer treatment.

In the field of cancer therapy, nanoparticle (NP)-based drug delivery systems have emerged as a promising strategy to enhance therapeutic efficacy while reducing the debilitating side effects associated with conventional chemotherapy. The effectiveness of these systems hinges on their ability to precisely accumulate at tumor sites and efficiently penetrate the complex tumor microenvironment. This targeting efficiency is not accidental but is profoundly governed by three fundamental physicochemical properties: size, surface charge, and shape. Decades of research have demonstrated that these parameters dictate NP interactions with biological systems, influencing circulation time, cellular uptake, biodistribution, and ultimately, therapeutic outcomes. Understanding the complex interplay between these properties is essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to design next-generation nanomedicines. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how size, surface charge, and shape influence nanoparticle targeting, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform rational NP design in cancer therapy research.

The Impact of Nanoparticle Size

Size-Dependent Cellular Uptake and Biodistribution

Nanoparticle size is a primary determinant in governing biological interactions, from systemic circulation and tissue penetration to cellular internalization. The size range of 10-200 nm is generally considered optimal for intravenous injection, as particles smaller than 10 nm are rapidly cleared by renal filtration, while those larger than 200 nm are prone to sequestration by the spleen and liver macrophages [14] [15]. The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, a cornerstone of passive tumor targeting, allows nanoparticles of approximately 10-150 nm to extravasate through the leaky vasculature of tumors and accumulate in the tumor interstitium [15]. However, a critical trade-off exists between accumulation depth and penetration within tumor tissue.

Table 1: Size-Dependent Effects on Nanoparticle Behavior

| Size Range | Key Findings on Targeting and Behavior | Experimental Model | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~100 nm | Highest cellular uptake rate and greatest distribution in liver; superior contrast enhancement in hepatic lesions. | In vivo mouse liver MRI | [14] |

| 25-50 nm | Exhibited similar accumulation and penetration in 3D tumor spheroids, outperforming larger NPs. | 3D Spheroid Models (A549 cells) | [16] |

| 100-200 nm | Limited penetration in 3D spheroids compared to smaller NPs. | 3D Spheroid Models (A549 cells) | [16] |

| < 10 nm | Effective for deep tissue penetration; 2 nm NPs accumulated more effectively than 6 nm and 15 nm particles. | 3D Spheroid Models | [16] |

| 10-150 nm | Optimal for prolonged circulation and accumulation in tumors via the EPR effect. | Review of NP delivery | [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Studying Size Effects

Synthesis of Size-Modulated Nanoparticles: A common method for generating a series of NPs with different sizes is by modulating reactant ratios. In a study on polyvinylpyrrolidone-coated iron oxide nanoparticles (PVP-IOs), the particle core size was controlled by varying the concentration of PVP to iron carbonyl (Fe(CO)₅) during thermal decomposition. Increasing the PVP concentration from 0.07 to 0.33 g/mL resulted in a decrease in core size from 65.3 nm to 7.6 nm [14]. The hydrodynamic diameter, which includes the core and the surface coating in a hydrated state, is typically measured using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and is more relevant for predicting in vivo behavior.

In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation:

- Cellular Uptake in 2D Models: Incubate different sized NPs with cancer cell monolayers (e.g., A549 lung carcinoma cells) for a set time (e.g., 3 hours). After washing away unbound NPs, the internalized NPs can be quantified via various methods, such as measuring intrinsic photoluminescence (for gold NPs) or iron content [16].

- Penetration in 3D Models: Multicellular tumor spheroids serve as a more physiologically relevant model. Spheroids are incubated with NPs for 24 hours, then washed, fixed, and analyzed using confocal fluorescence microscopy. An in-house algorithm can be used to analyze fluorescence images and quantify NP penetration depth from the spheroid periphery to its core [16].

- In Vivo Biodistribution and Imaging: NPs are administered intravenously to animal models. Their biodistribution and accumulation in organs like the liver, spleen, and tumors can be tracked over time using imaging techniques like Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). For instance, the transverse relaxivity (R2) of iron oxide NPs increases with larger core sizes, providing a darker contrast in T2-weighted MRI and enabling the quantification of liver accumulation [14].

The Role of Surface Charge

Charge-Mediated Interactions and Uptake

Surface charge, typically indicated by zeta potential, critically influences a nanoparticle's interaction with plasma proteins, blood circulation time, and cellular uptake. Positively charged (cationic) NPs generally exhibit superior cellular internalization due to strong electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged glycoproteins and phospholipids on cell membranes [17]. However, this advantage comes at a cost; cationic surfaces also promote non-specific adsorption of serum proteins (opsonins), leading to rapid clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) and shortened blood circulation [15] [17]. Conversely, neutral or slightly negatively charged NPs demonstrate longer circulation times due to reduced protein opsonization, but their cellular uptake is often less efficient.

Table 2: Surface Charge-Dependent Effects on Nanoparticle Behavior

| Surface Charge | Key Findings on Targeting and Behavior | Experimental Model | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Consistently superior accumulation and deeper penetration in 3D tumor spheroids compared to neutral and positive NPs. | 3D Spheroid Models (A549 cells) | [16] [18] |

| Positive | Enhanced cellular internalization in 2D cell cultures due to electrostatic adhesion with cell membranes. | 2D Cell Monolayers | [17] |

| Neutral/Negative | Prolonged blood circulation by resisting protein adsorption and clearance by the reticuloendothelial system (RES). | Review of NP pharmacokinetics | [15] [17] |

| Charge-Reversal | Neutral/negative in circulation (long half-life), converts to positive in acidic tumor microenvironment (enhanced uptake). | pH-responsive NP systems | [17] |

Smart Charge-Reversal Systems and Experimental Analysis

To harness the benefits of both neutral (long circulation) and positive (high uptake) charges, researchers have developed "charge-reversal" NPs. These systems are designed to be neutral or negatively charged during blood circulation but switch to a positive charge upon encountering specific stimuli in the tumor microenvironment (TME), such as its slightly acidic pH (pH 6.5-6.8) [17].

Mechanism and Materials: A common strategy involves functionalizing NP surfaces with pH-labile bonds, such as β-carboxylic amides. For example, polylysine (PLL) amided with 2,3-dimethylmaleic anhydride (DMMA) is negatively charged at physiological pH 7.4. In the acidic TME, the β-carboxylic amide bond hydrolyzes, shedding the DMMA group and regenerating the primary amine groups of PLL, which become protonated, resulting in a negative-to-positive charge reversal [17]. The kinetics of this conversion can be tuned by the chemical structure of the anhydride.

Experimental Protocol for Zeta Potential and Uptake:

- Zeta Potential Measurement: The surface charge of NPs is measured using a zeta potential analyzer. To confirm charge-reversal, NPs are incubated in buffers mimicking physiological (pH 7.4) and tumor (pH 6.5-6.8) conditions, and their zeta potential is tracked over time [17].

- Cellular Uptake Verification: The functional consequence of charge reversal is tested by incubating NPs with cells at different pH values. A significant increase in cellular internalization at acidic pH compared to neutral pH confirms the successful operation of the charge-reversal mechanism. Flow cytometry or confocal microscopy are standard techniques for this quantification [17].

Influence of Nanoparticle Shape

Shape Effects on Tumor Penetration

While less studied than size and charge, the shape of a nanoparticle is a critical factor influencing its dynamics in the bloodstream, margination towards vessel walls, and ability to penetrate dense tumor tissue. Spherical particles have been the most widely investigated due to their ease of synthesis. However, comparisons with non-spherical shapes like rods, disks, and filaments have revealed distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Key Findings: Recent systematic studies using 3D tumor spheroids have shown that spherical NPs outperform rod-shaped NPs in both tumor accumulation and penetration depth [16]. This finding challenges earlier hypotheses that suggested high-aspect-ratio particles might navigate tissue barriers more effectively. The superior performance of spheres may be attributed to more favorable Brownian motion and easier diffusion through the porous and fibrous extracellular matrix (ECM) of tumors.

Synthesis and Evaluation of Shape-Dependent Effects

Synthesis of Shape-Controlled Nanoparticles: Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are a popular model for shape studies due to their highly tunable morphology. Commercially available AuNPs can be acquired as spheres (various diameters) and nanorods (various aspect ratios) with controlled surface chemistry, allowing for direct comparison while isolating the effect of shape from other variables [16].

Experimental Workflow for Shape Comparison: The protocol for evaluating shape effects is similar to that for size. Spherical and rod-shaped NPs, with other properties (e.g., surface charge) kept constant, are incubated with 2D cell monolayers and 3D tumor spheroids. After incubation and washing, internalization in 2D and penetration depth in 3D are quantified using confocal microscopy and image analysis software. This direct comparison reveals that while rods might be internalized efficiently in 2D, their penetration in more realistic 3D models can be limited [16].

Integrated Design and Experimental Toolbox

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Nanoparticle Targeting Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | A biocompatible polymer coating for iron oxide NPs; improves dispersibility, stability, and blood circulation time. | PVP-IOs for liver MRI [14] |

| Carbodiimide Crosslinkers (e.g., EDC) | Enables covalent conjugation of antibodies or targeting ligands (e.g., peptides, transferrin) to NP surfaces for active targeting. | Antibody-conjugated NPs [19] |

| 2,3-Dimethylmaleic Anhydride (DMMA) | A pH-sensitive moiety used to create charge-reversal NPs; shields positive charge until reaching acidic TME. | pH-responsive PLL-DMMA [17] |

| A549 Lung Carcinoma Cells | A well-characterized cell line capable of forming compact, tumor-like spheroids for testing NP penetration in 3D models. | 3D spheroid penetration studies [16] |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | A highly tunable model system with intrinsic photoluminescence; ideal for isolating effects of size, shape, and charge without fluorophore labels. | Multi-parameter studies in 3D models [16] |

| Poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | A biodegradable and FDA-approved polymer for creating polymeric NPs; drug release kinetics can be tuned by molecular weight and lactide:glycolide ratio. | Polymer-based smart nanocarriers [9] |

Visualizing the Design Logic for Optimal Targeting

The following diagram synthesizes the experimental data and illustrates the logical relationship between nanoparticle properties and their resulting biological performance, guiding the design of NPs for optimal tumor targeting.

The pursuit of efficient nanoparticle targeting in cancer therapy is a multi-parameter optimization challenge. As this guide demonstrates, the physicochemical properties of size, surface charge, and shape are not independent levers but are deeply interconnected in their influence on the biological fate of NPs. The "perfect" nanoparticle does not exist; its design must be tailored to the specific therapeutic goal, whether it is broad tumor accumulation, deep tissue penetration, or efficient cellular internalization. The emerging trend is toward "smart" nanoparticles that can dynamically change their properties in response to the tumor microenvironment, such as charge-reversal systems. Furthermore, the use of advanced 3D models for preclinical testing is proving essential for obtaining predictive data for clinical translation. By systematically understanding and applying the principles outlined in this comparison guide, researchers can make informed decisions to engineer more effective, targeted nanomedicines for oncology.

Cancer remains a leading cause of mortality worldwide, accounting for approximately 10 million deaths in 2022, with projections indicating a rise to 70 million annual deaths by 2050 [20]. Conventional chemotherapy, while effective to varying degrees, suffers from significant limitations including lack of selectivity for tumor cells, inefficient drug delivery to tumor sites, and development of multi-drug resistance [9]. The complexity of the tumor microenvironment and individual genetic variations further complicate the development of effective treatments [9]. In response to these challenges, smart nanoparticles have emerged as a transformative drug delivery platform for precise cancer therapy.

Smart nanoparticles represent an advanced class of nanocarriers engineered to respond to biological cues or be guided by them, establishing an intelligent treatment modality [9]. Unlike conventional nanoparticles, these sophisticated systems can be triggered by specific stimuli and target specific sites with precise drug delivery control [9]. After modification or activation by corresponding factors, smart nanoparticles efficiently accumulate at target locations and release their therapeutic payloads in a controlled manner [9]. Their capability to co-deliver therapeutics and diagnostic reagents has significantly advanced the development of theranostics in oncology [9]. This review provides a comprehensive classification and comparison of smart nanoparticle systems—polymeric, lipid-based, inorganic, and hybrid—within the context of their targeting efficiency in cancer therapy research.

Classification and Characterization of Smart Nanoparticles

Polymeric Nanoparticles

Polymeric nanoparticles play a pivotal role in biomedical applications, bringing together biologists, chemists, engineers, and physicians in unique collaborative ways [9]. These nanoparticles offer several advantages over non-encapsulated drugs, including improved circulation time, enhanced stability, controlled structural decomposition, higher encapsulation rates, and reduced premature and nonspecific release kinetics [9]. The development of stimuli-responsive polymeric systems represents a significant advancement in smart nanocarriers for cancer therapy.

Polymeric nanoparticles can be synthesized with combinations of both inorganic and organic components to achieve synergistic properties [9]. For instance, the combination of multiple materials can alter biological distribution, improve solubility, and enhance system stability [9]. The ability to link materials with one another can prolong blood circulation while maintaining biological effects [9]. Synthetic tunability enables the creation of smart nanoparticles that can simultaneously serve several therapeutic or imaging goals by co-encapsulating various therapeutic compounds with different release profiles [9]. A key intelligent feature of these systems is their ability to be triggered by controlling local induction of endogenous physical parameters such as electrical, thermal, ultrasound, or magnetic energy [9].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Polymeric Nanoparticles

| Characteristic | Description | Impact on Cancer Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | Biodegradable polymers (PLGA, PLA, chitosan, alginate) [20] | Improved biocompatibility and reduced toxicity compared to non-biodegradable polymers |

| Drug Release Kinetics | Adjustable by molecular weight, lactide to ethyl ester ratio, and drug concentration [9] | Enables controlled release profiles tailored to specific cancer types |

| Surface Modification | PEGylation for stealth properties; ligand attachment for active targeting [9] | Prolonged circulation time and enhanced tumor-specific accumulation |

| Stimuli-Responsiveness | Response to pH, temperature, enzymes, or external triggers [9] | Precise drug release within tumor microenvironment |

| Manufacturing | Emulsion polymerization, solvent evaporation, salting-out, dialysis [9] | Scalable production with good repeatability |

Lipid-Based Nanocarriers

Lipid-based nanocarriers (LNs) represent one of the most established categories of nanocarriers with excellent biocompatibility profiles [21]. These systems are generally non-spherical in shape, determined by electrostatic interactions between polar/ionogenic phospholipid heads and the solvent, as well as non-polar lipid hydrocarbon moieties present in the solvent [21]. The unique physicochemical properties of lipid-based systems in the form of liposomes or solid core lipid nanoparticles make them outstanding candidates as carriers for drug delivery applications [21].

Liposomes

Liposomes, first developed in the 1960s, are composed of phospholipid bilayers similar to plasma membranes of human cells, granting them exceptional biocompatibility and the ability to promote drug diffusion across plasma membranes [21]. These self-assembled vesicles comprise one or multiple concentric lipid bilayers that enclose an aqueous core, typically ranging from 20 nm to over 1 μm in size [21]. This distinctive structure enables liposomes to hold and stabilize hydrophilic drugs in the aqueous core while encapsulating lipophilic drugs within the lipid bilayer, contributing to their remarkable versatility [21]. The landmark approval of Doxil by the FDA in 1995 as the first long-circulating liposome for cancer treatment paved the way for numerous liposomal formulations [21] [20]. When compared to free doxorubicin, Doxil significantly reduced cardiotoxicity and myelotoxicity while achieving higher drug concentrations in tumors [20].

Solid-Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs)

Solid-lipid nanoparticles (SLNs), developed in the 1990s, combine the advantages of polymer nanocarriers (strong drug loading capacity, controllable drug delivery) with the excellent biocompatibility of lipid emulsions [21]. The main feature of SLNs is that they contain lipids that remain solid at room temperature, typically composed of biocompatible substances such as triglycerides, fatty acids, steroids, and biowaxes [21]. Due to their small sizes and large surface area, SLNs are suitable for surface functionalization with ligands, antibodies, and other functional groups [21]. SLNs can be orally administered as aqueous dispersions or in dosage forms such as capsules, tablets, and pellets, positioning them at the forefront of potential applications in oral drug delivery systems [21].

Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) were developed as an enhancement to SLNs by replacing a fraction of solid lipids with liquid lipids to form a nanostructured matrix [21]. Unlike SLNs, the lipid matrix of NLCs consists of a mixture of solid and liquid lipids with controlled levels that possess improved capacity for bioactive retention along with controlled release attributes [21]. Since drugs generally have higher solubility in oil than in solid lipids, NLCs typically demonstrate stronger encapsulation ability for drugs compared to SLNs [21].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Lipid-Based Nanocarriers

| Parameter | Liposomes | Solid-Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) | Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Phospholipid bilayer with aqueous core [21] | Solid lipid matrix at room temperature [21] | Mixture of solid and liquid lipids [21] |

| Size Range | 20 nm to >1 μm [21] | 50-1000 nm [20] | 50-1000 nm [21] |

| Drug Encapsulation | Hydrophilic (aqueous core), hydrophobic (lipid bilayer) [21] | Predominantly hydrophobic drugs [21] | Enhanced for both hydrophilic and hydrophobic [21] |

| Loading Capacity | Limited bilayer space for hydrophobic drugs [21] | Moderate [21] | High [21] |

| Key Advantages | Excellent biocompatibility, versatile drug loading [21] | Good stability, controlled release, scale-up production [21] | Improved drug loading, reduced drug expulsion [21] |

| Clinical Status | Multiple approved products (e.g., Doxil) [20] | Under investigation | Under investigation |

Inorganic Nanoparticles

Inorganic nanoparticles constitute a distinct class of nanocarriers with unique physical properties that make them particularly valuable for theranostic applications in cancer therapy. This category includes mesoporous silica nanoparticles, gold nanoparticles, iron oxide nanoparticles, quantum dots, and carbon nanotubes [9]. These materials typically exhibit characteristics such as high surface-to-volume ratio, enhanced electrical conductivity, superparamagnetic behavior, spectral shift of optical absorption, and unique fluorescence properties [21].

Gold nanoparticles possess exceptional optical properties and surface plasmon resonance that can be exploited for both imaging and photothermal therapy applications [9]. Iron oxide nanoparticles offer superparamagnetic properties suitable for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic hyperthermia treatments [9]. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles feature tunable pore structures that enable high drug loading capacities and surface functionalization for targeted delivery [9]. Carbon nanotubes exhibit unique electrical and thermal properties, while quantum dots provide superior fluorescence for imaging and tracking applications [9].

Hybrid Nanoparticles

Hybrid nanoparticles represent a convergence of multiple material systems designed to overcome the limitations of single-component nanocarriers. These sophisticated systems combine polymers with inorganic or organic base systems, resulting in remarkable improvements in drug targeting capabilities [22]. The development of hybrid polymer materials can circumvent the need for synthesizing entirely new molecules—an expensive process that can take several years to reach proper elaboration and approval [22].

The combination of properties in a single hybrid system confers several advantages over non-hybrid platforms, including improvements in circulation time, structural disintegration resistance, high stability, reduced premature release, enhanced encapsulation rates, and minimized unspecific release kinetics [22]. Lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPHNs), for instance, combine the benefits of both liposomal and polymeric systems, exhibiting high drug-loading capacity, superior stability, enhanced biocompatibility, rate-limiting controlled release, prolonged drug half-lives, and improved therapeutic efficacy [20]. These hybrid systems effectively mitigate the individual disadvantages of their component materials while amplifying their beneficial characteristics [20].

Experimental Characterization Methodologies

Physicochemical Characterization Protocols

Comprehensive characterization of nanomaterial surfaces is critically important to establish structure-property relationships and provide feedback in nanomaterial design, as physiochemical characteristics directly affect performance [23]. The key parameters requiring analysis include size, shape, core structure, surface ligands, surface charge, hydrophobicity, ligand shell thickness, binding affinity, and surface morphology [23].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy provides comprehensive structural information by analyzing the chemical environment of nuclei and has become one of the most versatile techniques for characterizing surface ligand structures [23]. In nanomaterial characterization, NMR can confirm ligand immobilization, study ligand structure, differentiate between bound and unbound ligands, quantify bound ligands, understand ligand binding mode and dynamics, and study interactions with biomolecules [23].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare nanoparticle dispersions in deuterated solvents at concentrations sufficient to detect surface ligands (larger nanoparticles require more sample due to dilution of surface ligands by the bulk nanomaterial) [23].

- Data Acquisition: Conduct 1H NMR experiments to confirm successful surface modification by comparing functionalized nanomaterials with free ligands [23].

- Advanced Analysis: Employ 2D-NMR techniques (DOSY, NOESY, TOCSY, HSQC, ROESY) for additional structural information [23].

- Quantitative Analysis: Use peak integration for bound ligand quantification and T2 relaxation analysis to study chain packing density and headgroup motions [23].

One significant challenge in NMR characterization of nanomaterials is line broadening of ligand signals, which becomes more severe with increasing nanoparticle size due to slower rotational correlation times [23]. Murphy and colleagues demonstrated the application of 1H NMR to characterize (11-mercaptohexadecyl)trimethylammonium bromide (MTAB) on gold nanospheres, confirming ligand attachment and studying packing density in a particle size-dependent manner [23].

Surface Charge and Hydrophobicity Analysis

Surface charge significantly influences nanoparticle behavior in biological systems, affecting cellular uptake, biodistribution, and toxicity [23]. Zeta potential measurement represents the most common method for determining nanoparticle surface charge, reflecting the electrical potential at the slipping plane of particles in solution [23].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute nanoparticle dispersions in appropriate buffers to maintain physiological relevance while ensuring optimal concentration for measurement.

- Instrument Calibration: Standardize zeta potential analyzer using reference materials with known zeta potential values.

- Measurement Conditions: Conduct measurements at consistent temperature (typically 25°C) with multiple runs (minimum n=3) to ensure reproducibility.

- Data Analysis: Calculate mean zeta potential values and standard deviations across replicates; interpret results in context of surface functionality.

Hydrophobicity characterization typically involves hydrophobic interaction chromatography or fluorescence-based methods using environment-sensitive probes [23]. These techniques provide insights into how nanomaterials interact with biological membranes and proteins, crucial for understanding their behavior in vivo.

Targeting Efficiency Assessment

Evaluating the targeting efficiency of smart nanoparticles requires sophisticated experimental protocols that quantify accumulation at tumor sites and specific cellular uptake.

Experimental Protocol for In Vitro Targeting Assessment:

- Cell Culture Preparation: Establish appropriate cancer cell lines (e.g., MCF-7 for breast cancer, A549 for lung cancer) and maintain under standard conditions.

- Ligand Functionalization: Conjugate targeting ligands (antibodies, peptides, aptamers, folic acid, transferrin) to nanoparticle surfaces using appropriate chemistry [9] [20].

- Competitive Binding Assays: Incubate functionalized nanoparticles with target cells in the presence and absence of free ligands to demonstrate binding specificity.

- Cellular Uptake Quantification: Employ flow cytometry or confocal microscopy with fluorescently labeled nanoparticles to quantify internalization.

- Data Analysis: Calculate targeting efficiency as the ratio of cellular uptake between targeted and non-targeted formulations.

Experimental Protocol for In Vivo Targeting Assessment:

- Animal Model Establishment: Implement appropriate tumor xenograft models (e.g., nude mice with subcutaneous or orthotopic tumors).

- Nanoparticle Administration: Administer fluorescently labeled or radiolabeled nanoparticles via intravenous injection.

- Biodistribution Analysis: At predetermined time points, euthanize animals, collect major organs and tumors, and quantify nanoparticle accumulation using imaging or analytical techniques.

- Histological Validation: Process tumor tissues for histological analysis to confirm nanoparticle localization at cellular and subcellular levels.

- Statistical Analysis: Compare tumor accumulation between targeted and non-targeted systems using appropriate statistical tests.

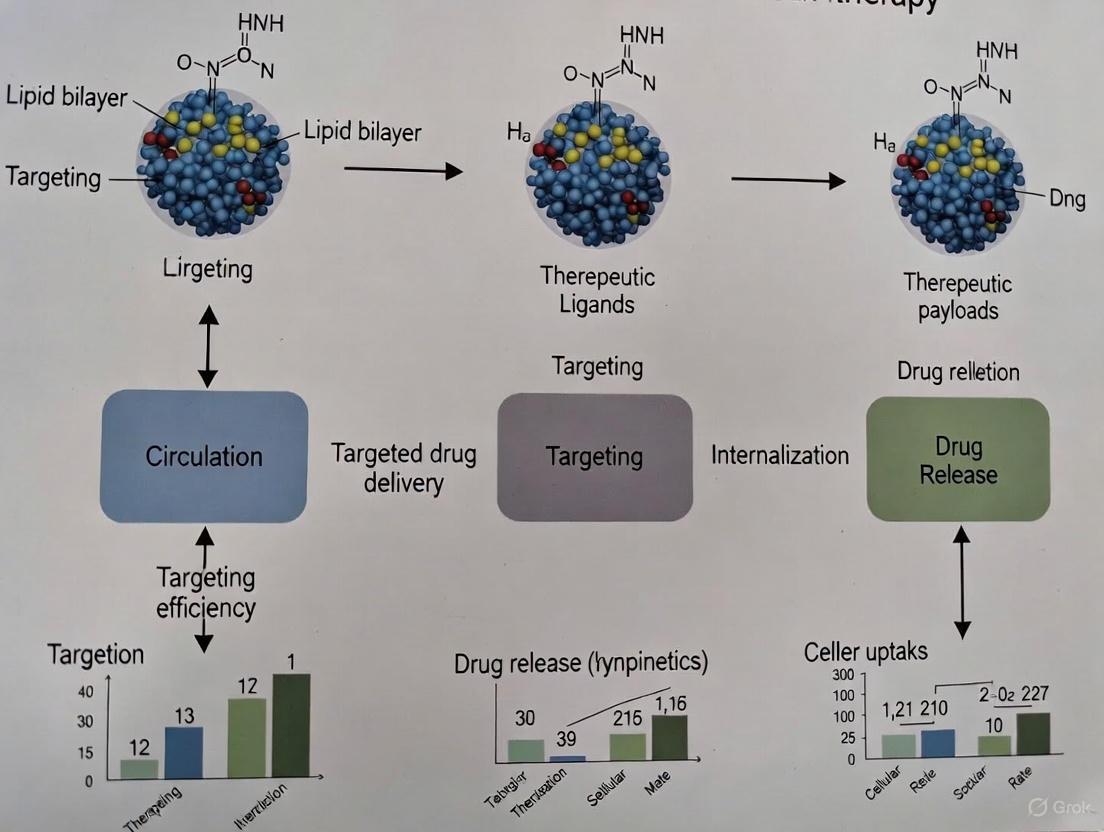

Diagram 1: Smart Nanoparticle Targeting Pathway in Cancer Therapy

Comparative Performance Analysis

Targeting Efficiency Across Nanoparticle Classes

The targeting efficiency of smart nanoparticles depends on multiple factors including size, surface properties, ligand density, and responsiveness to tumor microenvironment cues [9] [20]. Passive targeting leverages the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, which takes advantage of the leaky nature of tumor vasculature that allows nanoparticles to extravasate and accumulate in tumor tissue [20]. Active targeting incorporates specific ligands on nanoparticle surfaces that recognize and bind to receptors overexpressed on cancer cells [9].

Table 3: Targeting Efficiency of Smart Nanoparticle Classes

| Nanoparticle Class | Targeting Mechanisms | Ligand Functionalization | Experimental Targeting Efficiency | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymeric Nanoparticles | EPR, stimuli-responsive release (pH, temperature, enzymes) [9] | Antibodies, peptides, aptamers, folic acid, transferrin [9] | 3-5x higher tumor accumulation vs free drug [9] | Potential polymer toxicity, batch-to-batch variability |

| Liposomes | EPR, passive and active targeting [21] | Antibodies, peptides, carbohydrates [21] | 2-10x higher tumor concentration vs free drug (clinical data for Doxil) [21] [20] | Limited bilayer space for hydrophobic drugs, stability issues |

| Solid Lipid Nanoparticles | EPR, lymphatic targeting [21] | Proteins, surfactants, antibodies [21] | 3-8x increased bioavailability vs conventional formulations [21] | Drug expulsion during storage, low loading capacity |

| Inorganic Nanoparticles | EPR, magnetic guidance, external stimulus activation [9] | Silanes, thiols, phosphates, carboxylates [9] | 4-15x higher tumor accumulation with external magnetic field [9] | Potential long-term toxicity, slow biodegradation |

| Hybrid Nanoparticles | Combined mechanisms from component materials [22] | Multiple ligand types simultaneously [22] | 5-12x improved tumor suppression vs single-component systems [22] | Complex manufacturing, characterization challenges |

Drug Release Kinetics and Therapeutic Outcomes

Controlled drug release represents a critical parameter determining therapeutic efficacy and side effect profiles. Smart nanoparticles can be engineered to respond to various internal stimuli (pH, enzymes, redox potential) or external triggers (light, magnetic field, ultrasound) to achieve spatiotemporal control over drug release [9].

Diagram 2: Drug Release Mechanisms in Smart Nanoparticles

Experimental data from preclinical studies demonstrates that smart nanoparticles can maintain drug concentrations within the therapeutic window for extended periods, significantly improving treatment outcomes while reducing systemic toxicity. For example, DOXIL (pegylated liposomal doxorubicin) shows a significantly altered pharmacokinetic profile compared to free doxorubicin, with a half-life of approximately 55 hours versus 0.2 hours for the free drug, contributing to enhanced tumor accumulation and reduced cardiotoxicity [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development and evaluation of smart nanoparticles require specialized reagents and materials tailored to specific nanoparticle classes and research objectives.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Smart Nanoparticle Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Nanoparticle Development | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Materials | PLGA, PLA, PEG, chitosan, alginate, poly(amino acids) [9] [20] | Form nanoparticle matrix, control drug release kinetics, provide biodegradability | Molecular weight, lactide:glycolide ratio (for PLGA), degree of deacetylation (for chitosan) |

| Lipid Components | Phospholipids (HSPC, DPPC), cholesterol, solid lipids (triglycerides, fatty acids) [21] | Form lipid bilayers or solid matrices, encapsulate drugs, determine stability | Phase transition temperature, purity, oxidation susceptibility |

| Surface Ligands | Antibodies, peptides (RGD), aptamers, folic acid, transferrin [9] | Enable active targeting to cancer cells, enhance cellular uptake | Binding affinity, density on nanoparticle surface, orientation |

| Characterization Reagents | NMR solvents, zeta potential standards, fluorescence dyes [23] | Facilitate physicochemical characterization and tracking | Compatibility with nanoparticle materials, stability, interference |

| Stimuli-Responsive Elements | pH-sensitive linkers, enzyme-cleavable peptides, thermosensitive polymers [9] | Enable triggered drug release in response to specific stimuli | Sensitivity, specificity, response kinetics |

The classification of smart nanoparticles into polymeric, lipid-based, inorganic, and hybrid systems provides a framework for understanding their distinct characteristics and applications in cancer therapy. Each category offers unique advantages: polymeric nanoparticles excel in controlled release and functional versatility; lipid-based systems provide exceptional biocompatibility and clinical translation potential; inorganic nanoparticles offer unique physical properties for theranostics; while hybrid systems combine beneficial properties from multiple material classes [21] [9] [22].

The future of smart nanoparticles in cancer therapy lies in advancing personalization through patient-specific design, developing multi-responsive systems that react to multiple stimuli simultaneously, and creating adaptive nanoparticles capable of modifying their properties in response to changing biological environments [9] [24]. The integration of artificial intelligence in nanoparticle design and the development of computational models to predict nanoparticle behavior in biological systems represent promising avenues to accelerate clinical translation [9]. As characterization techniques continue to improve, providing deeper insights into nanomaterial-biological interactions, the rational design of smart nanoparticles with enhanced targeting efficiency and therapeutic outcomes will undoubtedly advance, ultimately benefiting cancer patients through more effective and less toxic treatment options.

The success of nanoparticle-based cancer therapeutics relies on their efficient tumor uptake and retention [25]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) represents a complex, dynamic ecosystem that plays a pivotal role in cancer progression, therapeutic resistance, and response to treatment [26] [27] [28]. For researchers developing nanomedicines, understanding the biological characteristics of the TME is paramount, as it creates substantial barriers that significantly limit nanoparticle accumulation at the tumor site [29] [27].

The TME is composed of both cellular and non-cellular components, including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), endothelial cells, pericytes, diverse immune cells (T cells, macrophages, dendritic cells), and the extracellular matrix (ECM) [27] [30]. This microenvironment is not merely a passive bystander but actively participates in creating a hostile milieu characterized by immunosuppression, hypoxia, acidosis, and abnormal vasculature [27] [31]. These interconnected features collectively impede nanomedicine delivery through physical barriers, biochemical resistance mechanisms, and immune-mediated clearance pathways [25] [29].

Despite promising in vitro results, the clinical translation of nanoparticle formulations remains limited, with many promising preclinical studies failing to achieve expected efficacy in clinical stages [25] [26]. This translation gap highlights the critical importance of understanding TME biology and developing sophisticated nanoparticle designs that can overcome these barriers for improved therapeutic outcomes in cancer patients.

Key Biological Characteristics of the TME That Hinder Nanoparticle Accumulation

Abnormal Tumor Vasculature and Hemodynamic Barriers

The tumor vasculature system exhibits significant structural and functional abnormalities that profoundly impact nanoparticle delivery [27] [31]. Unlike normal blood vessels, tumor vessels are typically disorganized, tortuous, and highly permeable, leading to heterogeneous blood flow and oxygen distribution [27]. This dysfunctional vascular network creates substantial challenges for nanoparticle delivery:

- Heterogeneous Distribution: The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, while historically leveraged for passive targeting, results in uneven nanoparticle distribution due to variable vessel permeability and regions of hypoperfusion [29].

- Elevated Interstitial Fluid Pressure: Leaky vasculature combined with impaired lymphatic drainage creates elevated interstitial fluid pressure, reducing convective transport and limiting nanoparticle penetration into the tumor core [29] [31].

- Inadequate Perfusion: The disorganized architecture with dead ends and shunts reduces effective perfusion, creating regions that nanoparticles cannot access through circulation [27].

Table 1: Vascular Abnormalities in the TME and Impact on Nanoparticles

| Vascular Abnormality | Impact on Nanoparticle Accumulation | Potential Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Structural disorganization | Heterogeneous distribution | Size-tunable nanoparticles |

| Increased permeability | Primarily peripheral accumulation | Multi-stage delivery systems |

| Elevated interstitial pressure | Reduced deep penetration | Vasculature normalization agents |

| Irregular blood flow | Inconsistent delivery | Stimuli-responsive release systems |

Dense Extracellular Matrix and Physical Barriers

The extracellular matrix in solid tumors undergoes significant remodeling, creating a dense physical barrier that severely restricts nanoparticle movement [27] [32]. CAFs are primarily responsible for secreting and cross-linking ECM proteins such as collagen, fibronectin, and hyaluronic acid, dramatically increasing tissue stiffness and forming a fibrotic capsule around the tumor [27] [30]. This ECM remodeling:

- Limits Diffusion: The dense, cross-linked matrix creates narrow interstitial spaces that physically obstruct nanoparticle transport, particularly for larger formulations (>50 nm) [27].

- Traps Nanoparticles Peripherally: Nanoparticles often become trapped in the perivascular regions, unable to penetrate deeper tumor regions where the most aggressive cancer cells typically reside [27].

- Promotes Drug Resistance: The physical barrier protects interior tumor cells from therapeutic agents, contributing to treatment resistance and disease recurrence [28].

The biomechanical properties of the ECM are increasingly recognized as a major determinant of nanoparticle distribution, with studies showing that stromal targeting approaches can enhance nanomedicine penetration and efficacy [27] [32].

Immune-Mediated Clearance and Phagocytic Activity

The TME contains numerous immune cells that can recognize and clear nanoparticles, significantly reducing their circulation time and tumor accumulation [25] [30]. The mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), particularly tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), plays a dominant role in this clearance mechanism [25] [27]. Key aspects include:

- MPS Recognition: Opsonins in the blood serum adsorb to nanoparticles, making them recognizable to macrophages in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow, leading to rapid clearance from circulation [25].

- TAM-Mediated Uptake: Once within the TME, TAMs can internalize nanoparticles before they reach cancer cells, effectively diverting them from their intended targets [25] [30].

- Ligand-Dependent Clearance: Functionalizing nanoparticles with targeting moieties can paradoxically increase immune recognition. For instance, RGD peptide-functionalized nanoparticles demonstrated enhanced clearance by the MPS despite improved cancer cell uptake in vitro [25].

This immune-mediated clearance represents a significant challenge, particularly for actively targeted nanoparticles, and underscores the importance of evaluating targeting strategies in immunocompetent models for physiologically relevant assessments [25].

Metabolic Dysregulation: Hypoxia and Acidosis

The TME exhibits profound metabolic alterations that directly impact nanoparticle behavior and efficacy [27] [28] [31]. Rapid tumor proliferation outstrips the oxygen supply, creating hypoxic regions that trigger a shift toward anaerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect), resulting in lactate accumulation and acidosis (pH 6.7-7.1) [27] [31]. These metabolic conditions:

- Promote Pro-Tumor Signaling: Hypoxia stabilizes hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) that drive the expression of pro-angiogenic factors, ECM remodeling enzymes, and immunosuppressive cytokines [27].

- Impair Immune Function: An acidic environment directly suppresses T-cell and natural killer (NK) cell function, reducing cytokine production and cytotoxic activity [30] [31].

- Alter Nanoparticle Performance: The acidic pH can affect nanoparticle stability, drug release kinetics, and surface chemistry, potentially compromising their therapeutic function [29].

Table 2: Metabolic Features of the TME Affecting Nanoparticle Performance

| Metabolic Feature | Effect on TME | Impact on Nanoparticles |

|---|---|---|

| Hypoxia | Upregulates HIF-1α, promoting angiogenesis and invasion | Can trigger release in hypoxia-responsive systems |

| Acidosis (pH 6.7-7.1) | Suppresses immune cell function, promotes invasion | Enables pH-triggered drug release in acidic compartments |

| Lactate accumulation | Creates immunosuppressive environment, drives fibrosis | Can affect surface charge and stability |

| Nutrient competition | Limits immune cell metabolism and function | May alter cellular uptake mechanisms |

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Evaluating Nanoparticle-TME Interactions

In Vitro Models: From Monolayers to 3D Systems

Advanced in vitro models provide valuable platforms for initial screening of nanoparticle interactions within TME-like conditions [25]. While traditional 2D monolayers offer simplicity and reproducibility, they lack the complexity of the native TME [25]. More physiologically relevant systems include:

- 3D Spheroid Models: These models replicate key in vivo characteristics of the TME, including concentration gradients, cellular heterogeneity, and intricate cell-cell interactions, all of which influence NP penetration and intracellular accumulation [25].

- Organoid Systems: Patient-derived organoids preserve aspects of the original TME architecture and cellular composition, serving as valuable avatars for predicting treatment response [29].

- Advanced Co-culture Systems: Incorporating multiple cell types (cancer cells, CAFs, immune cells) better mimics the cellular crosstalk within the TME and its impact on nanoparticle behavior [25].

In a comprehensive study evaluating RGD-functionalized gold nanoparticles (GNPs), both monolayer and 3D spheroid models of KPCY murine pancreatic cancer cells were utilized [25]. The researchers employed inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) to quantitatively measure GNP content in cells harvested at 1 h, 8 h, and 24 h timepoints, complemented by confocal imaging to confirm intracellular accumulation [25].

In Vivo Models: Importance of Immunocompetent Systems

The choice of in vivo models critically influences the assessment of nanoparticle performance, particularly regarding immune interactions [25]. While immunocompromised models (e.g., nude mice) are commonly used for their convenience, they do not accurately account for immune-related interactions, potentially leading to overestimation of targeting efficacy [25]. Key considerations include: