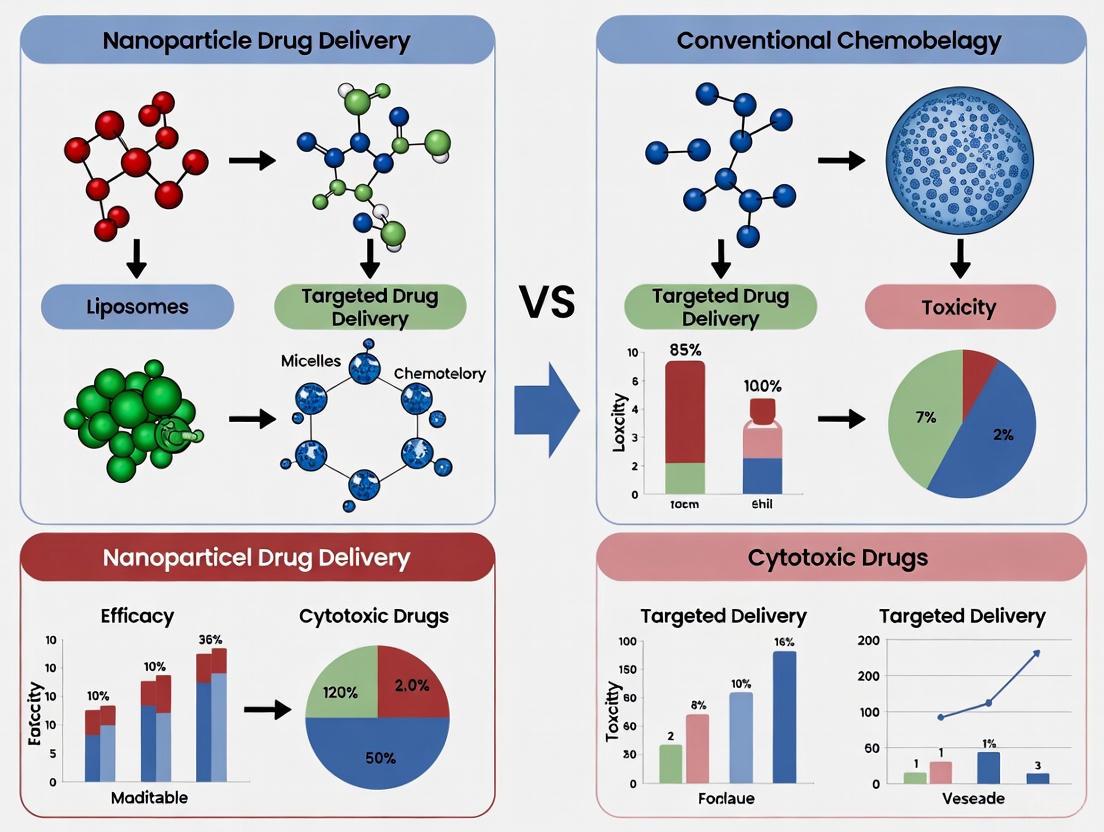

Nanoparticle Drug Delivery vs Conventional Chemotherapy: Mechanisms, Clinical Advances, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems and conventional chemotherapy for researchers and drug development professionals.

Nanoparticle Drug Delivery vs Conventional Chemotherapy: Mechanisms, Clinical Advances, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems and conventional chemotherapy for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of both modalities, detailing the limitations of traditional chemotherapeutic agents, including lack of specificity, multi-drug resistance, and systemic toxicity. The review covers the methodological advances in various nanoplatforms—such as lipid nanoparticles, polymeric NPs, and inorganic NPs—and their applications in enhancing drug solubility, stability, and targeted delivery. It further discusses troubleshooting strategies for overcoming biological barriers and optimizing nanoparticle design, and validates these approaches through comparative analysis of therapeutic efficacy, clinical trial outcomes, and approved nanotherapeutics. The synthesis of current progress and challenges aims to inform future research and clinical translation in oncology.

The Fundamental Divide: Exploring the Core Principles and Limitations of Conventional Chemotherapy

Historical Context and Evolution of Cancer Chemotherapy

The evolution of cancer chemotherapy represents a transformative journey from systemic cytotoxic agents to precisely targeted therapeutic approaches. This progression stems from the fundamental limitations of conventional chemotherapy, primarily its lack of specificity towards cancer cells and the consequent severe side effects that limit dosing and efficacy. Conventional chemotherapeutic agents, while effective at damaging rapidly dividing cells, indiscriminately affect healthy tissues with high mitotic activity, such as bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract, and hair follicles, leading to considerable toxicity [1]. The core challenge has been to increase drug accumulation in tumors while minimizing exposure to healthy tissues—a challenge that has motivated the development of nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems.

The emergence of nanomedicine in oncology marks a significant milestone in this evolutionary timeline. Nanoparticles (NPs), typically ranging from 1 to 100 nanometers in size, are engineered to improve drug stability, enhance targeted delivery to pathological sites, and control drug release kinetics [2]. This review comprehensively compares the performance of conventional chemotherapy versus nanoparticle-based therapeutic strategies, examining their efficacy, safety, and practical applications through objective experimental data and clinical evidence. By framing this comparison within the broader thesis of targeted versus systemic drug delivery, we aim to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a rigorous assessment of how nanotechnology is reshaping cancer treatment paradigms.

Historical Development of Conventional Chemotherapy

Conventional chemotherapy has its origins in the 1940s with the initial use of cytotoxic drugs against cancerous cells [1]. These chemotherapeutic agents are traditionally categorized based on their mechanism of action and chemical structure. The primary classes include: (1) antimetabolites (e.g., methotrexate, fludarabine, cytarabine) that interfere with DNA synthesis by mimicking essential cellular metabolites; (2) alkylating cytostatics (e.g., cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, melphalan) that directly damage DNA through alkylation; (3) natural preparations (e.g., vinblastine, etoposide, bleomycin) derived from natural sources that disrupt microtubule function or DNA integrity; and (4) hormonal agents (e.g., estrogens, aromatase inhibitors) that manipulate the endocrine system to combat hormone-sensitive cancers [1].

Despite their widespread use and clinical establishment, these conventional chemotherapeutic regimens face significant limitations. The primary constraint is their lack of specificity for cancer cells, resulting in damage to healthy tissues and severe side effects including myelosuppression, mucositis, diarrhea, and neurotoxicity [1]. Additionally, conventional administration methods—particularly bolus intravenous injection—can lead to sharp peak plasma concentrations that are directly correlated with cardiotoxicity, as demonstrated in studies of doxorubicin [3]. To mitigate these toxicological concerns, alternative administration strategies have been developed, including continuous infusion over 48-96 hours and metronomic chemotherapy (dividing the total drug dose into a series of consecutive infusions), which have shown reduced cardiotoxicity while maintaining therapeutic efficacy [3].

The limited bioavailability and poor accumulation of chemotherapeutic agents in tumor tissue further restrict their effectiveness. It is estimated that only a minimal fraction of administered chemotherapeutic drugs actually reaches the tumor site, with the remainder distributing throughout the body and causing systemic toxicity [3] [1]. This fundamental challenge of achieving therapeutic drug levels at the tumor site while sparing healthy tissues has driven the exploration of novel drug delivery systems, particularly nanoparticle-based platforms.

The Emergence of Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Systems

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems represent a paradigm shift in cancer therapy, designed to overcome the limitations of conventional chemotherapy through engineered targeting and controlled release. The therapeutic advantage of nanocarriers primarily stems from two key mechanisms: passive and active targeting.

Passive targeting leverages the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect, a physiological phenomenon unique to tumor tissues. As tumors rapidly grow, they develop abnormal, leaky vasculature with defective endothelial linings and impaired lymphatic drainage [1]. This pathological architecture allows nanoparticles (typically ranging from 10-200 nm) to extravasate and accumulate preferentially in tumor tissue, while their size prevents efficient clearance [4] [1]. The EPR effect was first clinically utilized in 1995 with the approval of PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil), establishing passive targeting as a foundational principle in nanomedicine [1].

Active targeting enhances this approach by functionalizing nanoparticle surfaces with ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides, aptamers) that specifically bind to receptors overexpressed on cancer cells [4]. This facilitates receptor-mediated endocytosis and increases cellular uptake of the therapeutic payload. Beyond these targeting strategies, nanoparticles offer additional advantages including improved drug solubility, protection of therapeutic agents from degradation, and controlled release kinetics that can be engineered to respond to specific stimuli in the tumor microenvironment (e.g., pH, temperature, or enzyme activity) [4] [5].

Table 1: Classification of Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Systems in Cancer Therapy

| Nanoparticle Type | Composition Materials | Key Characteristics | Clinical Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liposomes | Phospholipids, cholesterol | Spherical vesicles with aqueous core; high biocompatibility | Doxil (doxorubicin), Onivyde (irinotecan) |

| Polymeric NPs | PLGA, chitosan, polylactic acid | Controlled release kinetics; tunable degradation | Genexol-PM (paclitaxel) |

| Albumin-bound NPs | Albumin protein | Biocompatible; utilizes natural albumin transport pathways | Abraxane (paclitaxel) |

| Metallic NPs | Gold, silver, iron oxide | Unique optical/magnetic properties; surface functionalization | Various in clinical trials |

| Dendrimers | Polyamidoamine, polyethyleneimine | Highly branched, monodisperse structure; multifunctional surface | - |

| Micelles | Block copolymers | Core-shell structure; solubilize hydrophobic drugs | - |

Evolution of Stimuli-Responsive and Multi-Drug Nanoplatforms

The continuing evolution of nanoparticle technology has yielded increasingly sophisticated stimuli-responsive systems that release their payload in response to specific tumor microenvironment triggers. A notable innovation is the development of lactate-gated nanoparticles that exploit the "Warburg effect"—where cancer cells metabolize glucose to lactate, creating lactate-rich tumor microenvironments. These nanoparticles incorporate a lactate-specific switch comprising lactate oxidase (which breaks down lactate to generate hydrogen peroxide) and a hydrogen peroxide-sensitive molecular cap that controls drug release [6]. This design confines drug release predominantly to lactate-rich tumor regions, significantly reducing off-target toxicity [6].

Another significant advancement is the development of multi-drug nanomedicines that co-encapsulate two or more therapeutic agents within a single nanoformulation. A comprehensive meta-analysis of 273 pre-clinical tumor growth inhibition studies demonstrated that multi-drug nanotherapy outperforms single-drug therapy, multi-drug combination therapy, and single-drug nanotherapy by 43%, 29%, and 30%, respectively [2]. Importantly, co-encapsulating two different drugs in the same nanoformulation reduces tumor growth by a further 19% compared with administering two individually encapsulated nanomedicines [2]. This enhanced efficacy stems from the coordinated delivery of synergistic drug ratios to the same cellular targets, overcoming the pharmacokinetic disparities that plague conventional combination chemotherapy.

Comparative Efficacy Analysis: Conventional Chemotherapy vs. Nanoparticle-Based Approaches

Quantitative Assessment of Therapeutic Outcomes

Robust clinical evidence from meta-analyses and comparative studies demonstrates the superior efficacy of nanoparticle-based chemotherapy approaches compared to conventional formulations. A comprehensive meta-analysis incorporating 27 clinical studies with 3,124 patients with solid tumors revealed significantly improved outcomes with nanoparticle-based therapies across multiple efficacy endpoints [7].

Table 2: Meta-Analysis of Clinical Efficacy: Nanoparticle vs. Conventional Chemotherapy

| Efficacy Endpoint | Nanoparticle Therapy | Conventional Chemotherapy | Treatment Effect | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Survival (HR) | 0.78 (95% CI: 0.71-0.85) | Reference | 22% reduction in mortality risk | < 0.001 |

| Progression-Free Survival (HR) | 0.81 (95% CI: 0.73-0.89) | Reference | 19% reduction in progression risk | < 0.001 |

| Objective Response Rate | 58.3% | 46.7% | OR: 1.62 | < 0.001 |

| Grade ≥3 Hematologic Toxicities | 29.6% | 33.8% | - | - |

| Peripheral Neuropathy | 17.1% | 25.6% | - | - |

This meta-analysis established that nanoparticle-based chemotherapy significantly improves overall survival (HR: 0.78) and progression-free survival (HR: 0.81) compared to conventional chemotherapy, while also achieving a higher objective response rate (58.3% vs. 46.7%) [7]. The pre-clinical data corroborates these clinical findings, with combination nanotherapy reducing tumor growth to just 24.3% of controls, compared to 53.4% for free drug combinations and 54.3% for single-drug nanotherapy [2].

Safety and Toxicity Profiles

The improved safety profile of nanoparticle-based therapies represents one of their most significant advantages over conventional chemotherapy. The same meta-analysis revealed reduced incidence of severe hematologic toxicities (29.6% vs. 33.8%) and peripheral neuropathy (17.1% vs. 25.6%) in patients receiving nanoparticle-based therapies compared to conventional chemotherapy [7]. Although infusion-related reactions were slightly more frequent with nanoparticle formulations, the overall toxicity profile favored nanotherapies.

The cardiotoxicity associated with conventional doxorubicin administration exemplifies the safety advantages of nanoformulations. Clinical trials have demonstrated that continuous infusion reduces cardiotoxicity compared to bolus injection by decreasing peak plasma concentrations of the drug [3]. Nanoparticle delivery systems extend this principle further by providing sustained release and targeted delivery, potentially mitigating dose-limiting toxicities and enabling administration of higher effective drug doses [3] [6].

Experimental Models and Methodologies in Nanotherapy Research

In Vivo Tumor Models and Assessment Methods

Pre-clinical evaluation of nanoparticle-based cancer therapies employs well-established tumor models and standardized assessment protocols. The most frequently used in vivo models include xenograft models (human cancer cell lines inoculated in immunodeficient mice) and syngeneic allograft models (mouse cancer cells in immunocompetent mice), with the 4T1 triple-negative breast cancer model being particularly prevalent due to its robustness, spontaneous metastasizing capability, and close resemblance to human disease [2].

Tumor growth inhibition studies typically involve administering nanoformulations intravenously and monitoring tumor volume over time compared to control groups. Therapeutic efficacy is quantified as the percentage reduction in tumor growth relative to controls, with multi-drug nanotherapy demonstrating the most potent effects at 24.3% of control tumor growth [2]. Overall survival is assessed as the duration from treatment initiation to mortality, with combination nanotherapy showing superior outcomes—56% of studies demonstrated complete or partial survival compared to 20-37% for control regimens [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nanoparticle Cancer Therapy Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticle Materials | Drug carrier fabrication | Lipids (DSPC, cholesterol), polymers (PLGA, PLA), albumin, silica, gold |

| Therapeutic Agents | Cytotoxic payload | Doxorubicin, paclitaxel, 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan, platinum drugs |

| Targeting Ligands | Active targeting specificity | Antibodies, peptides, aptamers, folic acid, transferrin |

| Characterization Instruments | NP physicochemical analysis | DLS (size/zeta potential), TEM/SEM (morphology), HPLC (drug loading) |

| Cancer Cell Lines | In vitro and in vivo models | 4T1 (breast), CT26 (colon), MIA PaCa-2 (pancreas), PC-3 (prostate) |

| Animal Models | In vivo efficacy and toxicity | Immunodeficient mice (xenografts), immunocompetent mice (allografts) |

| Molecular Imaging Agents | Biodistribution and tracking | Fluorescent dyes (DiR, Cy5.5), radiolabels (99mTc, 64Ga), contrast agents |

Experimental Workflow for Nanoformulation Development

The standard methodological pipeline for developing and evaluating nanoparticle-based cancer therapies involves sequential phases of formulation, characterization, in vitro testing, and in vivo validation. The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive experimental workflow:

Nanoformulation Development Workflow

A representative example of this experimental approach is demonstrated in the development of albumin nanoparticles co-loaded with silver nanoparticles and 5-fluorouracil (5FU) for colon cancer treatment [8]. In this methodology, silver nanoparticles were first synthesized using green tea extract as a reducing agent, then characterized via UV-Vis spectrophotometry, TEM, SEM, and DLS, confirming spherical morphology with an average size of 89.9 nm [8]. Albumin nanoparticles were subsequently prepared using a desolvation method, with bovine serum albumin dissolved in deionized water, denatured at 40°C, then rapidly mixed with cold ethanol before cross-linking with glutaraldehyde [8]. The resulting nanoparticles demonstrated high encapsulation efficiency (>70-80%) and controlled release kinetics following the Higuchi model [8]. In a 21-day colon cancer model using Wistar rats with CT26-induced tumors, intravenous administration of the Ag-5FU-ANP formulation showed the most significant anticancer effect, reducing tumor size and weight compared to other treatment groups while exhibiting less severe hematological toxicity than 5FU monotherapy [8].

Clinical Translation and Real-World Applications

Integration into Oncological Practice

Nanoparticle-based therapies have progressively transitioned from experimental platforms to established clinical treatments, with several formulations now integrated into standard oncology practice. Notable examples include liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil), nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (Abraxane), and liposomal irinotecan (Onivyde), which have demonstrated improved therapeutic outcomes across various malignancies [4] [9]. These agents leverage the fundamental principles of nanomedicine to enhance drug delivery while mitigating toxicity.

In pancreatic cancer—one of the most challenging malignancies due to its dense stroma and poor drug penetration—nanoparticle-based therapies have shown particular promise. Real-world clinical evidence indicates that nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-PTX) and nanoliposomal irinotecan (nal-IRI) can improve survival outcomes while reducing toxicity compared to conventional treatments [9]. The recent approval of NALIRIFOX, a regimen incorporating liposomal irinotecan, for metastatic pancreatic cancer underscores the growing clinical acceptance of nanotherapeutics [9].

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite these advances, nanoparticle-based cancer therapies face several translational challenges. The manufacturing scalability of complex nanoformulations remains a significant hurdle, particularly for multi-drug systems and stimuli-responsive platforms [6] [2]. Additionally, patient selection strategies and predictive biomarkers for nanotherapy response require further refinement to maximize clinical benefit [9].

Future developments in cancer nanomedicine are likely to focus on several key areas: (1) personalized nanotherapies tailored to individual tumor characteristics and microenvironmental cues; (2) advanced multi-drug platforms that coordinate the delivery of complementary therapeutic agents; (3) novel targeting strategies that exploit emerging biological insights into cancer-specific biomarkers; and (4) integrated theranostic approaches that combine therapeutic and diagnostic capabilities within a single nanoformulation [4] [5]. As these innovations progress through preclinical development and clinical validation, nanoparticle-based approaches are poised to play an increasingly central role in oncological practice, potentially transforming cancer management paradigms over the coming decade [9].

The evolution of cancer chemotherapy from conventional cytotoxic agents to sophisticated nanoparticle-based delivery systems represents a fundamental advancement in oncological therapeutics. The comparative data comprehensively demonstrates that nanoparticle-based approaches offer significant efficacy and safety advantages over conventional chemotherapy, including improved overall survival, enhanced tumor growth inhibition, and reduced treatment-related toxicities. These benefits stem from the ability of nanoplatforms to overcome the fundamental limitations of traditional chemotherapy through targeted delivery, controlled release kinetics, and enhanced accumulation in tumor tissue.

While challenges remain in manufacturing scalability, patient selection, and long-term safety assessment, the continued refinement of nanoparticle technologies promises to address these limitations. The ongoing development of multi-drug nanotherapies, stimuli-responsive systems, and personalized nanomedicine approaches suggests that the evolution of cancer chemotherapy is far from complete. As nanoparticle-based strategies become increasingly integrated into standard treatment paradigms, they offer the potential to substantially improve outcomes for cancer patients while reducing the treatment burden associated with conventional chemotherapy.

Key Mechanisms of Cytotoxic Chemotherapeutic Agents

Cytotoxic chemotherapy remains a cornerstone of cancer treatment, functioning primarily by directly killing rapidly dividing cells, a hallmark of cancer [10]. The efficacy of these agents is fundamentally constrained by two major challenges: their lack of specificity for cancer cells, leading to damage of healthy tissues and dose-limiting toxicities, and the development of multifaceted drug resistance by tumors [10] [11]. A modern approach to overcoming these limitations involves the integration of nanotechnology for targeted drug delivery. This guide provides a structured comparison of the key mechanisms of conventional cytotoxic agents and explores how nanoparticle-based delivery systems are being engineered to enhance their therapeutic profile by improving specificity and circumventing resistance mechanisms.

Mechanisms of Action of Conventional Cytotoxic Agents

Conventional chemotherapeutic agents are categorized based on their primary biochemical targets and mechanisms of action, which ultimately trigger cell death, predominantly through the induction of apoptosis [11]. The major classes, their specific mechanisms, and cellular targets are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Mechanisms of Major Cytotoxic Chemotherapy Classes

| Drug Class | Specific Mechanism of Action | Key Cellular Target / Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Alkylating Agents (e.g., Temozolomide, Cyclophosphamide) | Cause DNA alkylation, leading to cross-linking of DNA strands and DNA breakage [10]. | DNA integrity; induces DNA damage response and apoptosis [10]. |

| Platinum Analogues (e.g., Cisplatin, Carboplatin) | Form intra- and inter-strand DNA crosslinks, destabilizing DNA structure [11]. | DNA replication and transcription; causes DNA damage [11]. |

| Antimetabolites (e.g., 5-Fluorouracil, Methotrexate, Gemcitabine) | Incorporate into DNA/RNA or inhibit enzymes (e.g., DHFR) crucial for DNA/RNA synthesis [10] [11]. | DNA/RNA synthesis; disrupts nucleotide metabolism [10]. |

| Topoisomerase Inhibitors (e.g., Irinotecan, Topotecan) | Inhibit topoisomerase enzymes (I or II), halting DNA unwinding and replication [10] [11]. | DNA replication and chromosome segregation [10]. |

| Antitumor Antibiotics (e.g., Doxorubicin) | Intercalate between DNA strands and inhibit topoisomerase II, interfering with DNA synthesis [10]. | DNA structure and enzyme function; generates DNA damage [10]. |

| Microtubule Inhibitors (e.g., Paclitaxel, Vinca Alkaloids) | Stabilize or disrupt microtubule dynamics, preventing proper mitotic spindle formation [10] [11]. | Mitosis; arrests cell division [10]. |

The Shift to Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Systems

Nanoparticle (NP) drug delivery systems are designed to improve the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of cytotoxic agents. They primarily leverage the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect for passive targeting, where NPs accumulate in tumor tissue due to its leaky vasculature and poor lymphatic drainage [12] [13]. Beyond passive targeting, active strategies functionalize NPs with ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides) for specific receptor binding on cancer cells, enhancing cellular uptake and specificity [12] [13].

Table 2: Types of Nanoparticle Carriers and Their Features for Chemotherapy Delivery

| Nanocarrier Type | Key Composition | Advantages for Cytotoxic Drug Delivery |

|---|---|---|

| Liposomes | Phospholipid bilayers forming an aqueous cavity [14]. | High biocompatibility; proven clinical success (e.g., Doxil) in reducing cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin [10] [14]. |

| Polymeric NPs | Biodegradable polymers (e.g., PLA, chitosan, albumin) [14]. | Controlled and sustained drug release; high drug-loading capacity [14]. |

| Stimuli-Responsive NPs | Materials that release drugs in response to tumor-specific stimuli (e.g., low pH, enzymes, metabolites) [6] [12]. | Enhanced spatial control over drug release; minimizes off-target effects. |

| Inorganic NPs | Gold, silica, or magnetic iron oxide particles [6] [13]. | Amenable to functionalization; can be used for combination therapies (e.g., photothermal + chemotherapy) [13]. |

Experimental Insights: A Protocol for Targeted Nano-Delivery

A cutting-edge example of nanoparticle engineering is the development of a lactate-gated silica nanoparticle for tumor-specific drug release, which exploits the high lactate concentration in tumors resulting from the Warburg effect [6].

Detailed Experimental Methodology

1. Nanoparticle Synthesis and Drug Loading:

- Porous Silica Nanoparticles are synthesized as the core carrier. Their mesoporous structure provides a high surface area for loading chemotherapeutic drugs like doxorubicin [6].

- The pores are then "capped" with a hydrogen peroxide-sensitive material.

2. In Vitro and In Vivo Testing:

- Cell Culture Models: The efficacy and specificity of the drug-loaded NPs are tested on cancer cell lines versus normal cell lines. Cytotoxicity is measured using assays like MTT or CellTiter-Glo.

- Animal Models: NPs are administered intravenously to mice bearing human tumor xenografts. The control group receives free drug (e.g., direct doxorubicin injection) [6].

- Biodistribution Analysis: Fluorescently labeled NPs or the drug itself are tracked using in vivo imaging systems (IVIS) to quantify accumulation in tumors versus major organs.

- Therapeutic Efficacy: Tumor volume is measured regularly, and animal survival is monitored over time.

3. Data Analysis:

- Drug concentration in tumors and plasma is quantified using HPLC-MS.

- Statistical comparisons (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA) are performed to confirm the significance of differences in tumor growth and drug accumulation between treatment groups [6].

Key Quantitative Findings from the Protocol

Table 3: Experimental Outcomes of Lactate-Gated Nanoparticle Delivery vs. Conventional Injection

| Performance Metric | Lactate-Gated Nanoparticle | Conventional Drug Injection |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor Drug Concentration | Delivered a 10-fold higher concentration of doxorubicin to the tumor site [6]. | Lower tumor accumulation due to non-specific distribution. |

| Therapeutic Efficacy | Significant slowing of tumor growth and increased survival in mouse models [6]. | Limited tumor growth inhibition at comparable doses. |

| Specificity of Release | Drug release was specifically triggered in the lactate-rich tumor microenvironment; remained capped in healthy tissues [6]. | Widespread, non-specific distribution and activity in both tumor and healthy tissues. |

Comparative Analysis: Mechanisms and Outcomes

The primary distinction between conventional and nano-delivered chemotherapy lies in the mechanism of delivery and its subsequent impact on therapeutic index and resistance.

Table 4: Mechanism-Based Comparison: Conventional vs. Nanoparticle-Delivered Chemotherapy

| Feature | Conventional Chemotherapy | Nanoparticle-Delivered Chemotherapy |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Relies on direct chemical interaction with cellular components (DNA, microtubules) [10] [11]. | Uses the NP as a vehicle to protect the drug and control its release location and kinetics. |

| Targeting Mechanism | None; systemic distribution. | Passive (EPR effect) and/or active (ligand-receptor) targeting to tumors [12]. |

| Therapeutic Index | Narrow, due to high off-target toxicity [10]. | Potentially wider, as targeting reduces healthy tissue exposure, allowing for higher, more effective doses [6]. |

| Addressing Drug Resistance | Limited; resistance often develops through mechanisms like efflux pumps [15]. | Can bypass efflux pumps by using alternative uptake pathways and delivering high local drug concentrations [14]. |

| Immune System Interaction | Can have immunostimulatory effects (e.g., immunogenic cell death) but also cause lymphodepletion [16]. | Can be engineered to enhance immunogenic cell death and co-deliver immunomodulators [16] [12]. |

Visualizing Key Pathways and Workflows

Mechanism of Cytotoxic Action and Resistance

The following diagram synthesizes the primary mechanisms by which cytotoxic agents kill cells and the common pathways cancer cells use to develop resistance [10] [15] [11].

Cytotoxic Action and Resistance Pathways

Nanoparticle Targeting and Drug Release Workflow

This diagram outlines the sequential process of how stimuli-responsive nanoparticles, such as the lactate-gated system, target and release drugs within the tumor microenvironment [6] [12].

NP Tumor Targeting Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 5: Essential Reagents and Materials for Investigating Cytotoxic Mechanisms and Nano-Delivery

| Research Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| Porous Silica Nanoparticles | Serves as the core scaffold for drug loading in stimuli-responsive delivery systems [6]. |

| Lactate Oxidase Enzyme | Key component of the molecular "switch"; converts high tumor lactate to hydrogen peroxide [6]. |

| H₂O₂-Sensitive Capping Material | Seals the NP pores; degradation by H₂O₂ triggers specific drug release in the tumor [6]. |

| Fluorescent Ubiquitination-based Cell Cycle Indicator (FUCCI) | Visualizes real-time cell cycle progression in live cells to study cell-cycle specific drug effects [11]. |

| Cultured Cancer Cell Lines | In vitro models for initial screening of drug/NP cytotoxicity, uptake, and mechanism of action studies. |

| Animal Tumor Xenograft Models | In vivo models (e.g., mice with human tumors) for evaluating NP biodistribution, efficacy, and toxicity [6]. |

Conventional chemotherapy, a cornerstone of cancer treatment for decades, is fundamentally constrained by two interconnected limitations: its lack of specificity for cancer cells and the resulting systemic toxicity. These cytotoxic drugs are designed to target rapidly dividing cells, a hallmark of cancer, but this mechanism fails to distinguish between malignant tissue and healthy cells with high proliferative rates, such as those in the bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract, and hair follicles [1]. This non-specific action leads to severe side effects—including bone marrow suppression, cardiotoxicity, and gastrointestinal reactions—which often limit the tolerable dose of the drug, compromise the patient's quality of life, and can lead to treatment failure [17] [1]. In response, nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems have emerged as a transformative strategy designed to overcome these hurdles by leveraging the unique pathophysiology of tumors to improve targeting and reduce off-site toxicity.

Comparative Analysis: Conventional Chemotherapy vs. Nanoparticle Drug Delivery

The following table summarizes the core differences between these two approaches, highlighting how nanotechnology addresses the central limitations of conventional therapy.

Table 1: A Comparative Overview of Conventional Chemotherapy and Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery

| Feature | Conventional Chemotherapy | Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery |

|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Systemic administration of free drug; affects all rapidly dividing cells [1]. | Drug encapsulated in a nanocarrier; relies on passive and/or active targeting to tumors [17] [4]. |

| Specificity | Low; lacks inherent targeting, leading to widespread damage to healthy tissues [1]. | High; enhanced by the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect and functionalization with targeting ligands [17] [4]. |

| Systemic Toxicity | High; dose-limiting toxicities are common (e.g., cardiotoxicity from doxorubicin) [3] [17]. | Reduced; minimizes exposure of healthy tissues to the cytotoxic drug [17] [1]. |

| Therapeutic Bioavailability | Limited; poor drug solubility and rapid clearance can reduce tumor accumulation [1]. | Improved; nanocarriers protect the drug, enhance circulation time, and increase tumor accumulation [17]. |

| Primary Hurdles | Toxicity to healthy cells, multi-drug resistance, limited bioavailability [3] [1]. | Heterogeneous EPR effect, potential nanoparticle toxicity, challenges in large-scale manufacturing [3] [18]. |

Quantitative Data: Evaluating Efficacy and Toxicity

Experimental data from in silico and clinical studies provide direct comparisons of drug distribution and toxicological outcomes.

Table 2: Experimental Data Comparison of Doxorubicin Delivery Modalities

| Delivery Modality | Peak Plasma Drug Concentration | Tumor Drug Accumulation | Key Toxicological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Bolus Injection | High | Moderate | Significant cardiotoxicity; life-cycle dose limited to <550 mg/m² [3] [17]. |

| Continuous Infusion (Conventional) | Lower | Moderate | Reduced cardiotoxicity compared to bolus injection [3]. |

| Liposomal Doxorubicin (e.g., Doxil) | Significantly lower | Higher than conventional | Marked reduction in cardiotoxicity while maintaining efficacy [17]. |

| Photothermal-Activated Nano-Delivery | Low | Highest among modalities | Minimized off-target toxicity due to localized, triggered release [3]. |

The efficacy of chemotherapy is directly constrained by potential toxicological implications [3]. For instance, the total lifetime dose of doxorubicin is limited due to its cardiotoxicity, which is directly related to its peak plasma concentration [3]. Clinical trials have demonstrated that administration methods which lower this peak concentration, such as continuous infusion, successfully reduce cardiotoxicity [3]. Nanoparticle formulations like PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) are explicitly designed to achieve this, significantly reducing cardiotoxicity while delivering the drug to the tumor site [17].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Comparison

To generate the comparative data cited in this field, researchers employ a range of standardized and advanced experimental protocols.

In Silico Modeling of Drug Transport

Objective: To computationally simulate and compare the distribution and efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs delivered via conventional methods versus nanoparticle systems within a realistic tumor microenvironment [3].

Methodology Details:

- Microvascular Network Generation: A semi-realistic, heterogeneous microvascular network is generated to represent the tumor's abnormal vasculature, which is a critical component for simulating drug delivery [3].

- Governing Equations: The model incorporates a set of mathematical equations to describe key physical and biological processes:

- Drug Exchange: Equations model the transport of the drug between the microvascular network and the tumor interstitium [3].

- Interstitial Transport: The diffusion and convection of the drug through the extracellular space are calculated [3].

- Cellular Uptake: The model includes terms for drug uptake by tumor cells [3].

- Binding Kinetics: The binding of the drug to intracellular and extracellular targets is simulated [3].

- Pharmacodynamics Evaluation: The anticancer effectiveness is not merely based on drug concentration. Instead, the density of viable tumor cells is determined by directly solving a pharmacodynamics equation based on the predicted intracellular drug concentration [3].

Visualization of Experimental Workflow:

In Vitro Cytotoxicity and Targeting Assessment

Objective: To experimentally evaluate the specificity and toxicity of nanoparticle formulations compared to free drugs using cell cultures.

Methodology Details:

- Cell Culture Setup: Experiments are conducted using both target cancer cell lines and non-malignant cell lines [18].

- Treatment Groups: Cells are exposed to:

- Free chemotherapeutic drug (e.g., doxorubicin, paclitaxel).

- Nanoparticle-encapsulated drug.

- Placebo nanoparticles (to assess nanocarrier toxicity).

- Untreated control [18].

- Viability Assay: After a defined incubation period, cell viability is quantified using standard assays such as the MTT or MTS assay, which measure metabolic activity [18].

- Targeting Efficiency: For actively targeted nanoparticles, the experiment includes a control with non-targeted nanoparticles to quantify the benefit of the targeting ligand. Flow cytometry and confocal microscopy are often used to visualize and quantify cellular uptake [17] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful research in this field relies on a specific set of reagents and materials, as detailed below.

Table 3: Key Reagents for Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function and Explanation |

|---|---|

| Liposomes (e.g., PEGylated) | Spherical vesicles with a lipid bilayer that encapsulates hydrophilic drugs in their aqueous core or hydrophobic drugs within the membrane. PEGylation ("stealth" coating) prolongs circulation time by reducing immune clearance [17]. |

| Polymeric Nanoparticles (e.g., PLGA) | Biodegradable and biocompatible polymers that form solid nanoparticles for sustained and controlled drug release. Their degradation rate can be tuned to control drug release kinetics [17]. |

| Targeting Ligands (e.g., Antibodies, Peptides) | Molecules (e.g., monoclonal antibodies, folic acid, RGD peptides) conjugated to the nanoparticle surface to enable active targeting by binding to receptors overexpressed on cancer cells [17] [4]. |

| Stimuli-Responsive Materials | Materials engineered to release their drug payload in response to specific internal (e.g., low pH, enzymes) or external (e.g., NIR light, magnetic field) triggers, enhancing spatial and temporal control [3] [4]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., Cyanine, FITC) | Used to label nanoparticles or drugs to track their distribution, cellular uptake, and biodistribution in in vitro and in vivo settings via fluorescence microscopy or imaging systems [18]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Versatile inorganic nanoparticles used for drug delivery, photothermal therapy (absorbing light and generating heat), and as contrast agents for imaging due to their unique optical properties [19]. |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Laser | An external stimulus used in photothermal therapy and for triggered drug release from light-sensitive nanocarriers (e.g., gold nanoparticles, thermosensitive liposomes). NIR light offers relatively deep tissue penetration [3]. |

Signaling Pathways and Logical Workflows

Understanding the mechanistic pathways of drug action and nanoparticle targeting is crucial for developing improved therapies.

Pathway of Chemotherapy-Induced Cytotoxicity

This diagram outlines the primary mechanism by which conventional chemotherapeutic agents like doxorubicin cause cell death, and how this leads to systemic toxicity.

Nanoparticle Targeting via the EPR Effect

The Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect is a fundamental principle that enables the passive targeting of nanoparticles to solid tumors.

The direct comparison presented in this guide unequivocally demonstrates that nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems represent a paradigm shift in addressing the historical limitations of conventional chemotherapy. By leveraging sophisticated targeting mechanisms like the EPR effect and active ligand-receptor interactions, nanocarriers significantly enhance the specificity of cytotoxic agents for tumor cells. This refined targeting directly translates to a superior therapeutic profile: reduced systemic toxicity and, as evidenced by clinical formulations like Doxil and Abraxane, the potential to maintain or even improve efficacy. While challenges in the heterogeneous EPR effect and nanoparticle biocompatibility remain active areas of research, the experimental data and methodologies outlined herein provide researchers with a clear framework for continuing to advance this critical field. The ongoing evolution of nanomedicine continues to hold the promise of transforming oncology treatment into a more precise, effective, and tolerable endeavor for patients.

The Challenge of Multi-Drug Resistance (MDR) in Tumors

Multidrug resistance (MDR) presents a formidable challenge in clinical oncology, directly undermining the efficacy of chemotherapy and contributing significantly to treatment failure. Current estimates indicate that approximately 90% of chemotherapy failures in advanced or metastatic cancer patients are attributable to MDR, which also accounts for more than 50% of failures in targeted therapies and immunotherapies [20] [21]. This resistance phenomenon occurs when tumor cells develop simultaneous resistance to multiple structurally and functionally unrelated chemotherapeutic agents, leading to disease progression, recurrence, and ultimately, patient mortality [22] [23]. The extensive clinical burden imposed by MDR has catalyzed the development of innovative therapeutic strategies, most notably nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems, which aim to overcome resistance mechanisms and restore chemotherapeutic efficacy through enhanced targeting and controlled drug release [12] [21].

Performance Comparison: Conventional Chemotherapy vs. Nanoparticle-Based Delivery

The limitations of conventional chemotherapy in overcoming MDR have prompted the development of nanoparticle-based delivery systems designed to enhance therapeutic outcomes. The table below provides a systematic comparison of their performance based on critical therapeutic parameters.

Table 1: Performance Comparison Between Conventional Chemotherapy and Nanoparticle-Based Delivery Systems in MDR Context

| Performance Parameter | Conventional Chemotherapy | Nanoparticle-Based Delivery |

|---|---|---|

| Targeting Efficiency | Low; nonspecific distribution [24] | High; passive (EPR effect) & active targeting [4] [12] |

| Intracellular Drug Accumulation | Reduced by efflux pumps (e.g., P-gp) [22] | Enhanced; avoids efflux pump recognition [22] [21] |

| Systemic Toxicity | High; dose-limiting side effects [24] [20] | Reduced; improved biodistribution [4] [25] |

| Circulation Time | Short; rapid clearance [12] | Prolonged; sustained release profiles [22] [12] |

| Capacity for Co-delivery | Limited by pharmacokinetic differences [20] | High; co-delivery of drugs & resistance modulators [22] [21] |

| Tumor Suppression in MDR Models | Often ineffective, leads to resistance [20] [21] | Significant improvement demonstrated preclinically [22] [25] |

| Overcoming Efflux Pumps | Inefficient; substrates for ABC transporters [21] [23] | Bypasses or inhibits pump activity [22] [23] |

Nanoparticle systems fundamentally alter drug pharmacokinetics and biodistribution. Their ability to preferentially accumulate in tumor tissue through the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect—a phenomenon arising from leaky tumor vasculature and impaired lymphatic drainage—provides a critical targeting advantage [12]. Furthermore, by encapsulating chemotherapeutic agents, nanoparticles can shield drugs from recognition by ATP-binding cassette (ABC) efflux transporters such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp), thereby increasing intracellular drug concentration and reversing a primary mechanism of MDR [22] [21].

Key Mechanisms of MDR and Nanoparticle Counter-Strategies

Molecular Foundations of Multidrug Resistance

Tumor cells deploy multiple interconnected mechanisms to evade chemotherapy-induced cell death. The major pathways include:

- ABC Transporter-Mediated Drug Efflux: Overexpression of membrane-bound efflux pumps like P-gp (ABCB1), MRP1 (ABCC1), and BCRP (ABCG2) uses ATP hydrolysis to actively expel a wide range of chemotherapeutic drugs from cancer cells, reducing intracellular concentration to sub-therapeutic levels [22] [25] [21].

- Dysfunctional Apoptotic Machinery: Evasion of programmed cell death occurs through upregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins (e.g., Bcl-2) and inactivation of tumor suppressor p53, making cells unresponsive to drug-induced damage [25] [23].

- Enhanced DNA Repair: Tumor cells can activate sophisticated DNA repair pathways to correct genetic damage inflicted by chemotherapeutic agents, thereby surviving the cytotoxic insult [20] [23].

- Tumor Microenvironment (TME) Adaptations: The acidic, hypoxic TME and cancer stem cells (CSCs) contribute to resistance by creating a protective niche and enabling tumor regeneration [25] [20].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms of MDR and how nanoparticle-based strategies counteract them.

Quantitative Efficacy of Different Nanoparticle Platforms

Various nanoparticle platforms have demonstrated distinct capabilities in reversing specific MDR mechanisms. The efficacy of these systems is quantified in preclinical models through parameters such as reversal fold (RF), which measures the increase in sensitivity of resistant cancer cells to a chemotherapeutic agent.

Table 2: Efficacy of Nanoparticle Platforms Against Specific MDR Mechanisms

| Nanoparticle Platform | MDR Mechanism Targeted | Therapeutic Payload | Key Experimental Finding | Reversal Fold (RF) / Efficacy Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liposomes [22] | Drug efflux (P-gp) | Doxorubicin (DOX) | Increased nuclear accumulation in MCF-7/Adr cells | Stronger cellular retention vs. free DOX [22] |

| Polymeric Micelles [22] | Drug efflux, Apoptosis evasion | Docetaxel, Autophagy inhibitors | Sequential release; synergistic effect in vitro | Prioritized release enhances sensitivity [22] |

| Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) [22] | Drug efflux | Doxorubicin | Enhanced uptake/retention in MDA435/LCC6/MDR1 cells | Higher cytotoxicity vs. free drug [22] |

| Polymer-Lipid Hybrid NPs (PLNs) [22] | Multiple mechanisms | DOX + GG918 (P-gp inhibitor) | Co-delivery in vitro and in vivo | Significant reversal effect in solid tumors [22] |

| Dual pH-Sensitive Polymers [24] | Tumor microenvironment | Doxorubicin | pH-triggered drug release in acidic TME | Improved tumor suppression, reduced systemic toxicity [24] |

| Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles [22] | Gene-based resistance | siRNA, CRISPR/Cas9 | Non-viral vector for gene editing | Silencing of MDR genes [22] |

The co-delivery strategy exemplified by polymer-lipid hybrid nanoparticles (PLNs) is particularly noteworthy. By simultaneously delivering a chemotherapeutic agent like doxorubicin and an efflux pump inhibitor like GG918, these systems achieve coordinated pharmacokinetics and synergistic action at the tumor site, effectively resensitizing resistant cancer cells [22]. Furthermore, stimuli-responsive systems, such as dual pH-sensitive polymers, exploit the acidic tumor microenvironment (pH ~6.5-7.0) to achieve precise, spatially controlled drug release, maximizing therapeutic impact while minimizing off-target effects [24].

Experimental Protocols for Key MDR Reversal Studies

Protocol: Evaluating MDR Reversal Using Doxorubicin-Loaded Liposomes

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the reversal of P-gp-mediated resistance in human breast cancer cells [22].

- Objective: To assess the ability of DOX-loaded liposomes to increase intracellular drug concentration and cytotoxicity in P-gp overexpressing MDR cell lines (e.g., MCF-7/Adr).

- Cell Lines and Culture: Use drug-sensitive (MCF-7) and corresponding MDR (MCF-7/Adr) human breast cancer cells. Culture cells in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Maintain MCF-7/Adr cells under selective pressure with doxorubicin.

- Nanoparticle Formulation: Prepare doxorubicin-loaded liposomes via thin-film hydration method. Incorporate cholesterol and polyethyleneglycol (PEG)-lipids to enhance rigidity and sequester the drug, inhibiting P-gp interaction [22].

- Treatment Groups:

- Free doxorubicin (solution)

- Doxorubicin-loaded liposomes

- Blank liposomes (negative control)

- Cellular Uptake and Retention Assay:

- Seed cells in multi-well plates and allow to adhere for 24 hours.

- Treat cells with equivalent DOX concentrations (e.g., 5 µM) from different formulations for 2-4 hours.

- For retention studies, incubate for 2 hours, replace medium with drug-free medium, and analyze DOX fluorescence at time points (0, 30, 60, 120 min) using flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy.

- Cytotoxicity Assessment (MTT Assay):

- Seed cells in 96-well plates.

- Treat with a concentration gradient of each formulation for 72 hours.

- Add MTT reagent and incubate for 4 hours. Solubilize formed formazan crystals with DMSO.

- Measure absorbance at 570 nm. Calculate IC50 values and Reversal Fold (RF) = IC50 (free DOX) / IC50 (DOX-liposomes).

- Key Analysis: Compare IC50 values and intracellular fluorescence intensity (indicative of DOX accumulation) between MCF-7 and MCF-7/Adr cells for each formulation. Effective MDR reversal is indicated by a lower IC50 and higher RF for DOX-liposomes in MDR cells.

Protocol: Assessing pH-Triggered Drug Release and Efficacy

This methodology evaluates the performance of dual pH-sensitive polymer nanoparticles, which are designed to release their payload specifically in the acidic tumor microenvironment [24].

- Objective: To demonstrate the pH-dependent drug release profile and enhanced antitumor efficacy of DOX-loaded dual pH-sensitive nanoparticles (pNP-DOX).

- Nanoparticle Synthesis: Synthesize dual pH-sensitive copolymers containing acid-labile linkers (e.g., hydrazone or acetal bonds). Formulate nanoparticles using nanoprecipitation or emulsion methods, loading DOX into the core [24].

- In Vitro Drug Release Study:

- Place a known amount of pNP-DOX in dialysis bags.

- Immerse bags in release buffer at different pH values: pH 7.4 (physiological), pH 6.5 (tumor microenvironment), and pH 5.0 (endolysosomal).

- Maintain under sink conditions with constant agitation at 37°C.

- Withdraw buffer samples at predetermined time points and replace with fresh buffer.

- Quantify released DOX using fluorescence or HPLC. Plot cumulative release vs. time to confirm accelerated release at acidic pH.

- In Vitro Cytotoxicity in 3D Spheroids:

- Generate MDR tumor spheroids using a low-adhesion 96-well plate with the liquid overlay method.

- Treat mature spheroids with free DOX and pNP-DOX at equivalent doses.

- Monitor spheroid growth and morphology over time using bright-field microscopy.

- Quantify cell viability after treatment using ATP-based assays (e.g., CellTiter-Glo 3D).

- Confocal Microscopy Analysis:

- Treat spheroids with fluorescently labeled formulations.

- After incubation, wash, fix, and image spheroids using confocal microscopy with Z-stacking.

- Analyze the penetration depth and distribution of the fluorescence signal within the spheroid. pNP-DOX is expected to show deeper penetration and more homogeneous distribution due to size shrinkage and charge reversal at tumor pH.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research into nanoparticle-based MDR reversal relies on a specific set of reagents, biological models, and analytical instruments.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Nanoparticle-Based MDR Investigations

| Category / Item | Specific Example | Function / Application in MDR Research |

|---|---|---|

| MDR Cell Lines | MCF-7/Adr (Breast), KBv200 (Epithelial) | In vitro models with proven P-gp overexpression for screening formulations [22]. |

| Chemotherapeutic Agents | Doxorubicin, Paclitaxel, Docetaxel | Model drug payloads; substrates for key efflux pumps like P-gp and BCRP [22] [24]. |

| Efflux Pump Inhibitors | GG918 (Elacridar), Verapamil, Tariquidar | Co-delivered with chemo-drugs in nanoparticles to block P-gp and reverse efflux [22] [21]. |

| Polymeric Materials | PLGA, PEG, pH-sensitive polymers (e.g., with hydrazone linkers) | Form nanoparticle matrix; PEG prolongs circulation, pH-sensitive polymers enable triggered release [24]. |

| Lipidic Materials | Phospholipids (e.g., DSPC), Cholesterol, PEG-lipids | Form liposomes and lipid nanoparticles; cholesterol enhances rigidity to evade P-gp [22]. |

| Characterization Instrument | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Measure nanoparticle size, charge (zeta potential), and visualize morphology [4]. |

| In Vivo MDR Models | Xenografts from MDR cell lines (e.g., in nude mice) | Preclinical models to evaluate tumor targeting, biodistribution, and efficacy of nano-formulations [22]. |

| Key Assays | MTT/XTT assay, Flow Cytometry, Confocal Microscopy | Assess cytotoxicity, measure drug uptake/retention, and visualize intracellular localization [22]. |

The workflow from formulation to efficacy assessment involves multiple steps, each requiring specific tools and techniques. The following diagram outlines this complex process and the key tools involved.

Poor Bioavailability and Solubility of Conventional Drugs

A primary challenge in modern oncology is the poor bioavailability and insufficient solubility of many conventional chemotherapeutic agents [26]. It is estimated that approximately 40% of commercially available pharmaceuticals and the majority of investigational drugs struggle with low solubility, which directly compromises their therapeutic effectiveness and often necessitates increased dosages that lead to detrimental side effects [26]. For drugs classified as Class II and IV under the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS), solubility and permeability limitations present significant barriers to achieving effective treatment concentrations at tumor sites [26]. These pharmacological challenges are compounded by the non-specific targeting of conventional chemotherapy, which affects both cancerous and healthy cells with high mitotic activity, leading to severe adverse effects including bone marrow suppression, gastrointestinal complications, and cardiotoxicity [3] [1] [14].

The limitations of conventional administration methods further exacerbate these issues. While intravenous injection remains the most common delivery method for anticancer drugs, the choice between bolus injection and continuous infusion significantly impacts toxicity profiles [3]. Clinical trials have demonstrated that continuous infusion reduces cardiotoxicity compared to bolus injection by decreasing peak plasma concentrations of drugs like doxorubicin, yet this approach still fails to address the fundamental problem of non-specific cellular targeting [3]. Additionally, the tumor microenvironment itself presents physiological barriers to effective drug delivery, including elevated interstitial fluid pressure and a dense extracellular matrix that restricts penetration of therapeutic agents [3]. These multifaceted challenges have prompted the development of nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems as a promising alternative to overcome the pharmacological and biological limitations of conventional chemotherapy.

Comparative Analysis: Conventional Drugs versus Nanoparticle Delivery

The following tables provide a comprehensive comparison between conventional drug delivery and nanoparticle-based approaches, examining key pharmacological parameters, therapeutic outcomes, and physical characteristics that directly impact clinical efficacy.

Table 1: Comparative Bioavailability and Efficacy Parameters

| Parameter | Conventional Chemotherapy | Nanoparticle Delivery | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioavailability | Low, particularly for BCS Class II/IV drugs [26] | Significantly enhanced via encapsulation and protection [26] [27] | Nanoemulsions of primaquine showed enhanced oral bioavailability [26] |

| Tumor Accumulation | Typically <5% of administered dose [3] | Up to 10-fold higher concentration in tumors [6] | Lactate-gated nanoparticles delivered 10x higher doxorubicin concentration [6] |

| Solubility Enhancement | Limited by chemical properties [27] | 1.5-3 fold improvement for poorly soluble drugs [28] | Metal-organic frameworks significantly enhanced solubility of Felodipine, Ketoprofen [27] |

| Therapeutic Window | Narrow due to systemic toxicity [3] | Broadened through targeted release [14] | Liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) reduced cardiotoxicity while maintaining efficacy [17] [14] |

| Cell Viability Reduction | Variable, dose-limited by toxicity [3] | 2.5-5 fold improvement in tumor cell kill [3] | Photothermal-activated nano-delivery showed superior tumor cell viability reduction [3] |

Table 2: Physical Properties and Delivery Characteristics

| Characteristic | Conventional Formulations | Nanoparticle Systems | Impact on Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size | Molecular to micron scale [28] | 10-100 nm optimal range [17] | Enables EPR effect; prevents renal clearance (<10 nm) and phagocyte clearance (>100 nm) [17] |

| Circulation Half-life | Short, rapid clearance [17] | Prolonged via PEGylation [17] | Increased tumor accumulation time; reduced dosing frequency [17] |

| Drug Release Profile | Immediate, uncontrolled [3] | Controlled, sustained, and stimuli-responsive [3] [4] | Maintains therapeutic concentration longer; reduces peak toxicity [3] |

| Tumor Penetration | Limited by physiological barriers [3] | Enhanced via size and surface engineering [12] | Superior interstitial transport despite high IFP and dense ECM [3] |

| Targeting Mechanism | None (passive distribution) [1] | Passive (EPR) + Active (ligand-receptor) [12] | Selective tumor cell targeting reduces off-target effects [12] |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Conventional Chemotherapy Administration Protocols

The administration of conventional chemotherapy follows standardized protocols that significantly impact both efficacy and toxicity. The most common methods include:

Bolus Injection: Direct intravenous injection of concentrated drug solution over 15-30 minutes, resulting in high peak plasma concentrations that maximize cytotoxic effects but increase toxicity risks, particularly cardiotoxicity for drugs like doxorubicin [3].

Continuous Infusion: Administration of the same total drug dose over extended periods (48-96 hours) via central venous catheter, which reduces peak plasma concentrations and associated cardiotoxicity while maintaining comparable therapeutic efficacy [3].

Metronomic Chemotherapy: Division of the total drug dose into a series of consecutive smaller infusions, which has been recommended as an effective approach to reducing tumor cells while minimizing toxicological implications according to in silico studies [3].

Clinical trials comparing these methodologies have demonstrated that continuous infusion significantly reduces cardiotoxicity compared to bolus injection. For instance, a study by Legha et al. investigating doxorubicin administration found that continuous infusion over 48-96 hours decreased plasma peak concentrations and correspondingly reduced the risk of cardiotoxicity compared to standard bolus injection at the same clinical dose [3].

Nanoparticle-Based Delivery Systems

Nanoparticle drug delivery systems employ sophisticated engineering approaches to overcome biological barriers:

Passive Targeting (EPR Effect): Utilization of the Enhanced Permeability and Retention effect, where nanoparticles (10-100 nm) preferentially accumulate in tumor tissues due to leaky vasculature and impaired lymphatic drainage [12]. This approach underpins FDA-approved nanomedicines including Doxil and Apealea [12].

Active Targeting Strategies: Functionalization of nanoparticle surfaces with ligands (antibodies, peptides, aptamers) that specifically bind to receptors overexpressed on cancer cells, enabling receptor-mediated endocytosis and enhanced intracellular uptake [12].

Stimuli-Responsive Drug Release: Design of "smart" nanoparticles that release their payload in response to specific tumor microenvironment triggers such as pH, temperature, or enzyme activity [3] [4]. For instance, photothermal-activated nanocarriers rapidly release drugs when heated beyond the carrier's melting point using external energy sources like near-infrared lasers [3].

Intravascular Drug Release Paradigm: Development of larger nanocarriers designed for prolonged circulation that release drugs directly within the tumor vascular network, bypassing the interstitial barriers that limit conventional nanoparticle penetration [3].

Advanced Nano-Formulation Techniques

The production of effective nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems requires specialized manufacturing approaches:

Supercritical Nanonization: Processing of drug particles using supercritical carbon dioxide (Sc-CO2) as a green technology for particle size reduction to nanoscale dimensions, significantly enhancing solubility through increased surface energy [28]. Machine learning models like EPA-DT, EPA-TS, and EPA-GPR have been successfully employed to predict drug solubility in supercritical solvents with high accuracy (R² > 0.95) [28].

Hybrid Nanoparticle Systems: Combination of different nanomaterial classes to create hybrid systems that integrate the advantages of each component, such as lipid-polymer hybrids that offer high drug-loading capacity, enhanced stability, and controlled release profiles [17] [14].

Biomimetic Coating Strategies: Application of cell membranes from various cell types (stem cells, blood cells, cancer cells) onto nanoparticle surfaces, enabling them to mimic biological functions and enhance homing to specific tissues while evading immune detection [12].

Visualization of Key Mechanisms

EPR Effect in Tumor Targeting

Diagram Title: EPR Effect in Tumor Targeting

Lactate-Gated Nanoparticle Drug Release

Diagram Title: Lactate-Gated Nanoparticle Drug Release

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Thermosensitive Nanocarriers | Drug release triggered by temperature increase | Photothermal therapy; studied under NIR laser irradiation at 37-42°C range [3] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Surface coating to reduce opsonization and extend circulation half-life | PEGylation of liposomes and polymeric NPs to evade immune clearance [17] |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Laser | External energy source for precise spatiotemporal control of drug release | Penetrates tissue at greater depth than visible light; activates photothermal nanocarriers [3] |

| Lactate Oxidase Enzyme | Key component in metabolic targeting systems | Converts lactate to hydrogen peroxide in lactate-gated nanoparticles for tumor-specific release [6] |

| Supercritical Carbon Dioxide | Green processing solvent for pharmaceutical nanonization | Production of nanoscale drug particles with enhanced solubility properties [28] |

| Targeting Ligands (Peptides, Antibodies) | Surface functionalization for active targeting | Specific binding to receptors overexpressed on cancer cells (e.g., folate, transferrin receptors) [12] |

| Polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) | Biodegradable polymer for controlled drug release | FDA-approved polymeric nanoparticle platform with tunable degradation kinetics [17] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide-Sensitive Materials | Capping agents for stimuli-responsive drug release | Degrade in presence of H₂O₂ to release payload in specific microenvironments [6] |

The comparative analysis between conventional drug delivery and nanoparticle-based systems reveals significant advantages in addressing the persistent challenges of poor bioavailability and solubility in cancer therapy. Quantitative data demonstrates that nanoparticle approaches can achieve up to 10-fold higher drug concentrations in tumor tissues while simultaneously reducing toxic side effects through controlled release mechanisms [6]. The development of sophisticated targeting strategies, including EPR-mediated passive accumulation and active targeting through surface ligands, has enabled more precise delivery of therapeutic agents to malignant cells while sparing healthy tissues [12].

Future directions in nanoparticle drug delivery research focus on multi-stage targeting systems that address tissue, cellular, and subcellular localization challenges simultaneously [12]. The integration of biomimetic strategies, such as cell membrane-coated nanoparticles, and the application of artificial intelligence in nanoparticle design represent promising avenues for enhancing therapeutic precision [12]. Additionally, the development of metabolic targeting approaches that exploit biochemical differences between cancer and normal cells, such as the Warburg effect, offer new opportunities for tumor-specific drug release with minimal off-target effects [6]. As these technologies continue to evolve, nanoparticle-based delivery systems are poised to fundamentally transform cancer treatment paradigms by maximizing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing the debilitating side effects that have long constrained conventional chemotherapy.

The Rationale for Targeted Drug Delivery Systems

Conventional chemotherapy, a cornerstone of cancer treatment for decades, operates on a fundamental and systemic principle: the administration of cytotoxic drugs that preferentially affect rapidly dividing cells. While this approach can be effective, its lack of specificity is a critical flaw, leading to widespread damage to healthy tissues and resulting in severe side effects such as bone marrow suppression, hair loss, and gastrointestinal reactions [29]. Furthermore, the therapeutic efficacy of conventional chemotherapy is constrained by several biological factors, including drug resistance and the complex, heterogeneous nature of the tumor microenvironment (TME) [3]. The pursuit of more effective and less toxic alternatives has catalyzed the development of targeted drug delivery systems (DDS), with nanoparticle-based therapies at the forefront. These systems are engineered to enhance drug bioavailability, direct therapeutic agents specifically to tumor sites, and control the release of payloads, thereby improving therapeutic outcomes while minimizing off-target effects [30] [31]. This guide provides an objective comparison between conventional chemotherapy and modern nano-based targeted drug delivery, framing the discussion within the ongoing research paradigm that seeks to redefine oncology therapeutics.

Objective Comparison: Conventional Chemotherapy vs. Nano-Targeted Delivery

The following tables synthesize key performance metrics and characteristics from experimental and clinical studies to provide a direct comparison between these two therapeutic strategies.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Performance Metrics

| Performance Metric | Conventional Chemotherapy | Nano-Targeted Drug Delivery |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor Accumulation | Low and non-specific [3] | Enhanced via EPR effect; ~0.7% of administered dose reaches tumor [3] [32] |

| Cellular Uptake | Passive diffusion | Can be enhanced via active targeting ligands [4] [12] |

| Therapeutic Specificity | Low; affects all rapidly dividing cells [29] | High; can be engineered for tissue, cell, and organelle specificity [12] |

| Systemic Toxicity | High (e.g., cardiotoxicity from doxorubicin) [3] [29] | Reduced (e.g., liposomal doxorubicin shows lower cardiotoxicity) [29] |

| Mechanism to Overcome Drug Resistance | Limited | Multiple: Inhibits drug efflux pumps, enables combination therapy [29] |

| Drug Circulation Time | Short, rapid clearance [30] | Prolonged, enhanced stability and half-life [29] |

Table 2: Comparison of Formulation and Clinical Translation Characteristics

| Characteristic | Conventional Chemotherapy | Nano-Targeted Drug Delivery |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Solubility & Stability | Often requires toxic solvents [29] | Nanocarriers enhance solubility and protect drugs [31] [29] |

| Delivery Modalities | Primarily bolus injection or continuous infusion [3] | Multi-functional carriers (liposomes, polymeric NPs); stimuli-responsive release [3] [30] |

| Clinical Approval Rate | High, established history | Relatively low; only a fraction of pre-clinical designs are approved [12] |

| Manufacturing Complexity | Standardized | Complex; challenges with scalability and batch-to-batch consistency [12] |

| Targeting Mechanism | Relies on systemic exposure | Passive (EPR effect) and Active (ligand-receptor binding) [4] [12] |

Experimental Support and Methodologies

In Silico Modeling of Drug Delivery Efficacy

Objective: To computationally compare drug bioavailability and tumor cell kill efficacy between conventional chemotherapy and photothermal-activated nano-sized targeted drug delivery.

Methodology:

- A semi-realistic, heterogeneous microvascular network was generated to model the tumor microenvironment, incorporating key physical and biological processes such as interstitial fluid flow, drug binding to proteins, and thermal effects [3].

- Conventional Chemotherapy Simulation: Doxorubicin was administered via single and multiple bolus injections, as well as continuous infusion. The model calculated drug transport from the vasculature to the interstitium and subsequent uptake by tumor cells [3].

- Nano-Targeted Delivery Simulation: The intravascular release of doxorubicin from thermosensitive nanocarriers (e.g., ThermoDox) was modeled. A near-infrared (NIR) laser was used to simulate raising the temperature at the tumor site above the carrier's melting point, triggering rapid drug release into the tumor's vascular network [3].

- Pharmacodynamic Analysis: The density of viable tumor cells was determined by solving pharmacodynamics equations based on the predicted intracellular drug concentration for each strategy [3].

Key Results:

- The simulation demonstrated that photothermal-activated intravascular drug release significantly increases drug concentration in the tumor interstitium compared to classical chemotherapy administration routes [3].

- This targeted approach resulted in a higher predicted tumor cell kill efficacy due to improved drug bioavailability at the target site [3].

Experimental Protocol for Evaluating Nano-Drug Delivery

Objective: To experimentally assess the in vitro and in vivo performance of a targeted nano-drug delivery system.

Protocol Outline:

Nanoparticle Synthesis & Characterization:

- Formulation: Silk fibroin particles (SFPs) are synthesized using a microfluidics-assisted desolvation technique. Drugs (e.g., Curcumin and 5-FU) are encapsulated during the process [31].

- Characterization: The size, polydispersity index, and zeta potential of the nanoparticles are measured using dynamic light scattering. Morphology is analyzed via electron microscopy (SEM/TEM). Drug encapsulation efficiency is quantified [4] [31].

In Vitro Cytotoxicity and Targeting Assessment:

- Cell Culture: Breast cancer cells (e.g., MDA-MB-231) and non-cancerous mammary cells are cultured.

- Cytotoxicity Assay: Cells are treated with free drugs, blank nanoparticles, and drug-loaded nanoparticles. Cell viability is measured after 24-72 hours using MTT or AlamarBlue assays. Results show that CUR/5-FU-loaded magnetic SFPs induced cytotoxicity and G2/M cell cycle arrest in breast cancer cells while sparing non-cancerous cells [31].

- Cellular Uptake: To confirm targeting, fluorescently labelled nanoparticles, with and without targeting ligands, are incubated with cells. Uptake is visualized using confocal microscopy and quantified by flow cytometry [31] [29].

In Vivo Efficacy and Targeting:

- Animal Model: Tumor-bearing mice (e.g., xenograft models) are utilized.

- Drug Administration & Biodistribution: Mice are divided into groups receiving saline, free drug, non-targeted nanoparticles, and targeted nanoparticles. For some groups, a magnet is placed over the tumor to guide magnetic SFPs. In vivo, this magnetic guidance enhanced tumor-specific drug accumulation and increased tumor necrosis [31].

- Efficacy Monitoring: Tumor volume is tracked regularly, and at the endpoint, tumors are harvested for histological analysis (e.g., H&E staining, TUNEL assay for apoptosis) to assess therapeutic efficacy and damage to healthy organs [31].

Visualization of Key Concepts

The EPR Effect and Targeting Strategies

Diagram 1: Targeting Mechanisms. This diagram illustrates the primary strategies for targeted drug delivery: passive targeting via the EPR effect, active targeting using ligand-receptor binding, and stimuli-responsive drug release.

Nanoparticle Trafficking and Subcellular Targeting

Diagram 2: Nanoparticle Trafficking. This workflow outlines the journey of a therapeutic nanoparticle from systemic circulation to its ultimate subcellular target, highlighting key biological barriers and processes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Targeted Drug Delivery Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid) (PLGA) | Biodegradable polymer matrix for nanoparticle formation; enables controlled drug release. | Commonly used for formulating polymeric nanoparticles encapsulating chemotherapeutics [30]. |

| DSPE-PEG2000 | Lipid-PEG conjugate used to functionalize liposomes and other nanocarriers; improves stealth properties and circulation time. | A key component in PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) to reduce immune clearance [29]. |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | Natural polysaccharide used as a targeting ligand; binds to CD44 receptors overexpressed on many cancer cells. | Coated on nanoparticles (e.g., LicpHA) to achieve active targeting and enhanced cellular uptake [31] [12]. |

| N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) Esters | Chemistry for covalent conjugation of targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides) to nanoparticle surfaces. | Used to functionalize polymeric nanoparticles with anti-EGFR antibodies for targeted therapy [29]. |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Dyes (e.g., Cy7) | Fluorescent probes for non-invasive imaging of nanoparticle biodistribution and tumor accumulation in vivo. | Tracks the real-time distribution of injected nanoparticles in small animal models using an IVIS imaging system [3]. |

| Thermosensitive Liposomes (e.g., ThermoDox) | Nanocarriers designed to release their payload upon heating to mild hyperthermic temperatures (~40-42°C). | Studied in combination with external heating sources for triggered drug release in tumors [3]. |

| Folic Acid | A common targeting moiety conjugated to nanoparticles; folate receptors are frequently overexpressed in cancers. | Used to create actively targeted nanoparticles for delivery of drugs and imaging agents to tumor cells [4] [12]. |

Engineering Solutions: A Deep Dive into Nanoparticle Platforms and Targeting Mechanisms

Conventional chemotherapy, characterized by the systemic administration of free drugs, often suffers from poor solubility, rapid metabolism, non-specific distribution, and severe off-target toxicity. These limitations significantly hinder therapeutic efficacy and patient quality of life [33]. Nanocarrier-based drug delivery systems (NDDS) represent a transformative advancement designed to overcome these challenges. By engineering materials at the nanometer scale (typically 1-1000 nm), these systems enhance drug solubility, protect therapeutic agents from degradation, and enable targeted delivery to specific tissues [33] [34]. A key advantage in oncology is the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect, which allows nanocarriers of 60-150 nm to passively accumulate in tumor tissues due to leaky vasculature and impaired lymphatic drainage [35] [36]. This results in improved drug concentrations at the target site while minimizing exposure to healthy tissues, thereby enhancing the therapeutic index and reducing side effects [35] [33]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of four major nanocarrier platforms—liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs), polymeric nanoparticles, and metallic nanoparticles—focusing on their performance data, experimental protocols, and applications in cancer research.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Nanocarrier Platforms

The following tables summarize the key characteristics and quantitative performance data of the four nanocarrier platforms, based on current research and clinical applications.

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Clinical Status of Nanocarrier Platforms

| Parameter | Liposomes | Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) | Polymeric Nanoparticles | Metallic Nanoparticles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition | Phospholipids, Cholesterol [33] [37] | Solid lipids (e.g., triglycerides) [33] | Biodegradable polymers (e.g., PLGA, Chitosan) [38] [33] | Gold, Silver, Iron Oxide [33] |

| Structure | Spherical phospholipid bilayers enclosing an aqueous core [35] | Solid lipid core stabilized by surfactants [33] | Solid colloidal matrix [33] | Solid inorganic core [36] |

| Common Sizes | 50 - 1000 nm [33] | ~50 - 1000 nm [33] | 10 - 1000 nm [38] [39] | 10 - 100 nm [36] |

| Drug Loading | Hydrophilic (aqueous core), Hydrophobic (lipid bilayer) [33] | Predominantly lipophilic drugs [33] | Entrapment within polymer matrix or surface adsorption [33] | Surface adsorption or conjugation [33] |

| Clinical Status | Multiple FDA-approved (e.g., Doxil, AmBisome) [37] | Extensive research, limited clinical approvals [33] | Extensive research, some clinical approvals (e.g., PLGA-based) [38] | Preclinical and clinical trials, mainly for theranostics [36] [33] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance and Experimental Data Comparison

| Parameter | Liposomes | SLNs | Polymeric Nanoparticles | Metallic Nanoparticles |