Nanocrystal Synthesis Methods Compared: Yield Optimization for Biomedical Applications

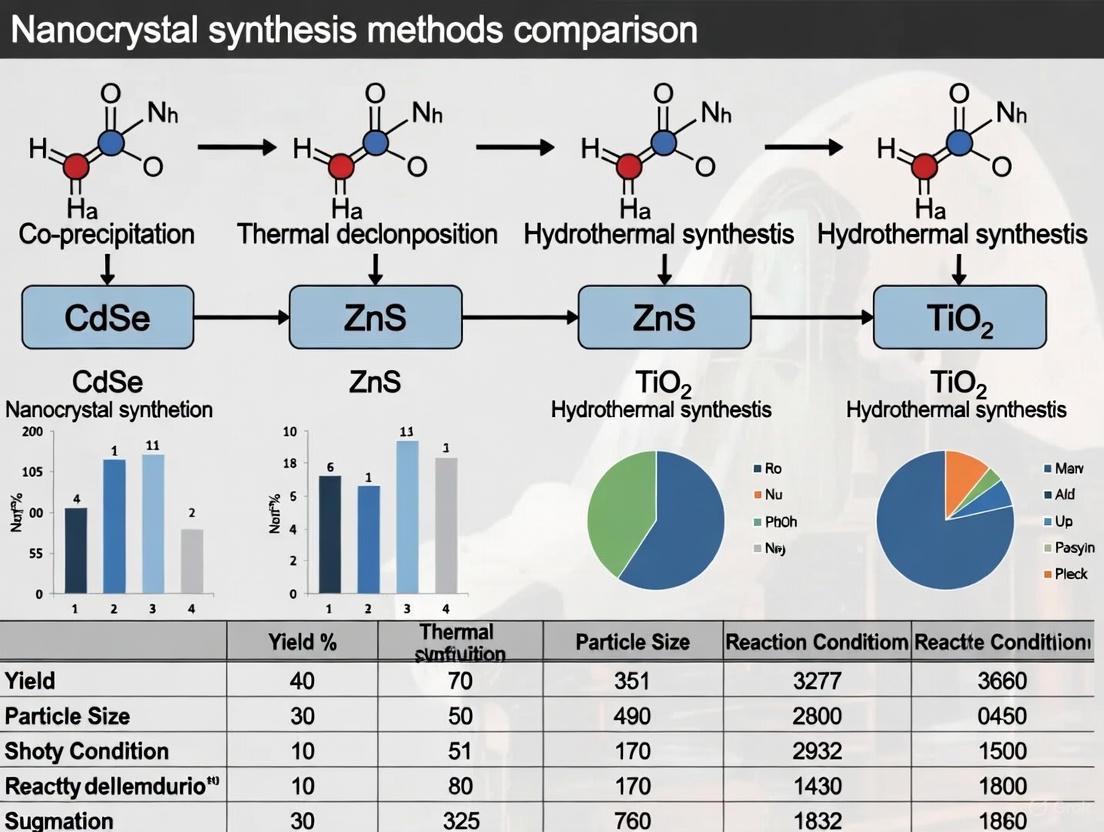

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of modern nanocrystal synthesis methods, with a focused analysis on optimizing yield and key properties for biomedical and drug development applications.

Nanocrystal Synthesis Methods Compared: Yield Optimization for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of modern nanocrystal synthesis methods, with a focused analysis on optimizing yield and key properties for biomedical and drug development applications. We explore foundational principles, from general phase-transfer strategies to the latest autonomous self-driving laboratories, and detail methodological advances in producing metal, semiconductor, and cellulose nanocrystals. The content systematically addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization parameters, including solvent selection, precursor choice, and surface engineering, and delivers a validated comparative analysis of yields, scalability, and material performance across techniques. Designed for researchers and scientists, this review synthesizes current knowledge to guide the selection and refinement of synthesis protocols for high-yield production of nanocrystals tailored for clinical research.

Core Principles and Emerging Frontiers in Nanocrystal Synthesis

Nanocrystals are a fundamental class of nanomaterials, typically defined as crystalline particles with at least one dimension between 1 and 100 nanometers [1] [2]. Their exceptionally small size, approaching the atomic scale, results in unique optical, electronic, and chemical properties that are distinct from those of their bulk material counterparts [3]. In biomedical fields, these properties are being harnessed for revolutionary applications in targeted drug delivery, advanced diagnostic imaging, and regenerative medicine [4].

Table 1: Unique Properties of Nanocrystals and Their Biomedical Implications

| Unique Property | Scientific Basis | Biomedical Significance | Exemplary Nanocrystal Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Confinement | Size-dependent discrete energy levels due to confinement of electron-hole pairs (excitons) [1]. | Enables tunable fluorescence for multiplexed bioimaging and biosensing; emission color can be precisely controlled by varying crystal size [5] [1]. | Semiconductor Quantum Dots (QDs) [1]. |

| Large Surface-to-Volume Ratio | A significant proportion of atoms are located on the surface rather than within the crystal lattice. | Enhances loading capacity for drugs and targeting ligands; improves catalytic efficiency for biosensing applications [4] [3]. | Gold Nanoparticles, Silicon Nanocrystals [4] [6]. |

| Tunable Surface Plasmon Resonance | Coherent oscillation of conduction electrons at the nanoparticle surface upon interaction with light [4]. | Used for colorimetric biosensors (e.g., lateral flow tests) and photothermal therapy for cancer [4]. | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [4] [7]. |

| High Photostability | High resistance to photobleaching due to their inorganic crystalline structure. | Superior to organic dyes for long-term, real-time tracking of biological processes in cells and tissues [1]. | Quantum Dots, Carbon Dots [1] [8]. |

Synthesis Methods and Experimental Protocols

The synthesis of nanocrystals is a critical step that dictates their size, shape, and properties. Methods are broadly categorized into physical, chemical, and biological approaches, as well as emerging hybrid techniques [2]. The following experimental protocols illustrate key methodologies cited in recent research.

Protocol 1: Alkoxy Ligand-Based Synthesis of Water-Soluble Nanocrystals

This novel one-step method addresses the critical challenge of producing nanocrystals stable in biological environments [3].

- Objective: To synthesize hydrophilic nanocrystals in a single step, eliminating the need for post-synthesis ligand exchange.

- Materials:

- Precursor metals (e.g., for quantum dots or gold nanoparticles).

- Alkoxy ligands (contain oxygen atoms for water compatibility).

- Standard chemistry lab solvents.

- Method:

- Combine precursor metals with alkoxy ligands in a single reaction vessel.

- The polar nature of the alkoxy ligands, with oxygen atoms that form hydrogen bonds with water, inherently makes the resulting nanocrystals hydrophilic.

- Purify the synthesized nanocrystals.

- Key Outcomes: This method produces nanocrystals that are immediately water-soluble, highly stable (functional for months), and generate biodegradable byproducts, dramatically reducing environmental waste compared to traditional hydrocarbon ligand methods [3].

Protocol 2: Response Surface Methodology (RSM) for Optimizing Silicon Nanocrystal (SiNC) Synthesis

This protocol uses a statistical design-of-experiments technique to model and optimize synthesis parameters [6].

- Objective: To elucidate the relationship between precursor chemistry, polymer structure, and the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of alkyl-passivated SiNCs.

- Materials:

- Trichlorosilane (precursor).

- Methanol and Water (solvents and reactants).

- Forming gas (95% N₂ / 5% H₂).

- 1-dodecene (for surface passivation).

- Method:

- Systematically vary the molar ratios of trichlorosilane, water, and methanol to synthesize 15 different silsesquioxane polymer precursors.

- Analyze the polymer structure (cage vs. network content) using FTIR spectroscopy.

- Pyrolyze the polymers at 1100°C under a forming gas atmosphere to form SiNCs embedded in a silica matrix.

- Liberate the SiNCs by etching with hydrofluoric (HF) acid.

- Passivate the surface through thermal hydrosilylation with 1-dodecene to render them colloidally stable.

- Characterize the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of the final alkyl-stabilized SiNCs.

- Use RSM to model the relationship between precursor ratios, polymer structure, and PLQY.

- Key Outcomes: The study found that higher proportions of methanol and water in the precursor mixture resulted in more network-type polymer structures, which yielded SiNCs with higher PLQYs (ranging from ~3% to 10%) [6].

Protocol 3: Autonomous Phase Mapping for Gold Nanoparticle (AuNP) Synthesis

This protocol leverages machine learning and closed-loop experimentation to efficiently navigate complex synthesis landscapes [7].

- Objective: To autonomously map the synthesis pathways for colloidal gold nanoparticles with target morphologies and optical properties.

- Materials:

- Gold precursors (e.g., Chloroauric acid).

- Silver nitrate (AgNO₃) and Ascorbic acid (shape-directing agents).

- Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, a surfactant).

- Seed nanoparticles.

- Method:

- Pre-train a Neural Process model on a prior dataset of nanoparticle UV-Vis spectra to learn a set of 'basis' spectral representations.

- Implement a closed-loop workflow integrating:

- Automated Synthesis: Robotically preparing AuNPs with varying concentrations of AgNO₃ and ascorbic acid.

- Characterization: Using UV-Vis spectroscopy to measure the plasmonic resonance of the synthesized AuNPs.

- Data-Driven Decision-Making: The pre-trained model, now fine-tuned with new AuNP data, predicts spectral outcomes and guides the scheduler to select the next most informative experiments.

- The system iterates until it can satisfactorily predict phase boundaries and structural outcomes across the compositional space.

- Key Outcomes: This approach efficiently constructs "phase maps" that reveal design rules for AuNP morphology (e.g., spherical to rod-like transitions) and enables "retrosynthesis"—optimizing compositions to achieve a target plasmonic resonance spectrum [7].

Biomedical Applications and Performance Comparison

The unique properties of nanocrystals have led to their integration into a wide array of biomedical applications, where they often outperform traditional materials and methods.

Table 2: Performance of Nanocrystals in Key Biomedical Applications

| Application | Traditional Method / Material | Nanocrystal-Based Alternative | Comparative Experimental Data & Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Delivery | Free drugs; Liposomes [4]. | Polymeric NPs (e.g., PLGA); Carbon Nanotube-Graphene hybrids [4]. | Brain Cancer Treatment: Nanocarriers enabled longer drug circulation, crossed protective barriers, and directly targeted cancer cells [4]. Tumor Targeting: An injectable nano-particle generator (iNPG-pDox) efficiently targeted breast cancer lung metastases, showing significant treatment efficacy [1]. |

| Bioimaging & Diagnostics | Organic fluorescent dyes (e.g., Fluorescein, Rhodamine) [1]. | Quantum Dots; Carbon Dots; Upconversion Nanocrystals [1]. | Superior Photostability: QDs do not photobleach like organic dyes [1]. High Sensitivity: A MMP-2 sensitive QD nanoprobe successfully detected tumors overexpressing the MMP-2 enzyme [1]. Deep Tissue Imaging: Upconversion nanomaterials injected into mice produced high-contrast deep optical imaging results [1]. |

| Photothermal Therapy (PTT) | Chemotherapy; Radiation therapy [4]. | Gold Nanospheres/Rods; Carbon Nanotubes [4]. | Precise Cancer Cell Destruction: Specially prepared gold nanoparticles absorb near-infrared light and generate heat to destroy cancer cells with minimal damage to surrounding healthy tissues [4]. |

| Biosensing | ELISA; Colorimetric assays. | Gold Nanoparticle (AuNP) biosensors [4]. | Rapid Detection: AuNPs were used in certain COVID-19 test kits, producing visible color changes upon virus detection due to their localized surface plasmon resonance, enabling trace-level detection [4]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

This table details essential materials used in the synthesis and application of nanocrystals for biomedical research, as derived from the featured experimental protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Nanocrystal Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Exemplified Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Trichlorosilane | A molecular precursor for forming the silicon-oxygen backbone of silsesquioxane polymers. | Serves as the primary silicon source in the synthesis of polymer precursors for Silicon Nanocrystals (SiNCs) [6]. |

| Alkoxy Ligands | Ligands containing oxygen atoms that confer water solubility and stability to nanocrystals during and after synthesis. | Used in a novel single-step synthesis method to produce nanocrystals that are inherently stable in biological aqueous environments [3]. |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | A shape-directing agent in the seed-mediated growth of metallic nanocrystals. | Critical for controlling the morphology of Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs), facilitating the transition from spheres to rods [7]. |

| 1-Dodecene | A long-chain alkene used in surface functionalization via hydrosilylation. | Employed for thermal hydrosilylation to passivate the surface of SiNCs with alkyl chains, rendering them colloidally stable and modulating their optical properties [6]. |

| Hydrogen Silsesquioxane (HSQ) | A commercial preceramic polymer used as a precursor for silicon nanocrystals. | Pyrolyzed at high temperatures under a forming gas atmosphere to produce size-tunable SiNCs embedded in a silica matrix [6]. |

| Gold Seed Nanoparticles | Small, crystalline gold nanoparticles that serve as nucleation sites for further growth. | The foundational structure in seed-mediated growth protocols for producing gold nanorods and other anisotropic shapes [7]. |

The precise synthesis of nanocrystals is a cornerstone of advanced materials research, with phase-transfer and separation mechanisms playing a pivotal role in determining final product characteristics. These interconnected processes govern the transition of nanoparticles between immiscible phases and their subsequent purification, directly impacting crystallinity, size distribution, and surface functionality—parameters essential for biomedical and electronic applications [9]. As nanotechnology advances, the ability to control these mechanisms has become increasingly crucial for producing nanocrystals with tailored properties, driving innovation across drug delivery, diagnostics, and energy applications [10].

Phase-transfer strategies enable the migration of nanoparticles from organic synthesis environments to aqueous phases compatible with biological systems, while separation techniques purify and classify nanocrystals based on subtle differences in physical properties [9]. The synergy between these processes forms a critical pathway in nanocrystal fabrication, particularly for applications requiring precise dimensional control and surface engineering [11]. This review systematically compares contemporary phase-transfer and separation methodologies, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to inform synthesis strategy selection for specific application requirements.

Comparative Analysis of Phase-Transfer Mechanisms

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Phase-transfer mechanisms facilitate the movement of nanocrystals or their precursors across phase boundaries, typically from organic to aqueous environments—a transition essential for biological applications [9]. These processes overcome the thermodynamic barriers of immiscible phases through specialized interfacial interactions. Flash nanoprecipitation (FNP) represents one advanced strategy, achieving rapid phase transfer via turbulent mixing to produce nanoparticles with controlled hydrodynamic diameters and high colloidal stability [9]. This method enables precise size control and high nanocrystal loadings, making it particularly suitable for biomedical applications where consistent nanoparticle characteristics are critical.

Surface modification approaches constitute another fundamental strategy, where hydrophobic nanocrystals are rendered water-dispersible through ligand exchange or polymer encapsulation [9]. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) coatings, for instance, provide a biocompatible interface while maintaining the core nanocrystal properties. The effectiveness of these transfer mechanisms depends heavily on the surface chemistry of the starting nanocrystals and the hydrophobicity balance between the core material and coating agents [9]. Alternative methodologies include phase-transfer catalysis (PTC), which employs catalysts like quaternary ammonium salts to shuttle reactants across phase boundaries, though this approach is more commonly applied in oxidative desulfurization processes than in nanocrystal synthesis [12].

Performance Comparison of Phase-Transfer Strategies

Table 1: Comparison of Phase-Transfer Mechanisms for Nanocrystals

| Mechanism | Typical Hydrodynamic Size Range | Key Advantages | Limitations | Optimal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flash Nanoprecipitation (FNP) | 250 nm and above | Scalable, precise size control, high colloidal stability | Requires specialized mixing equipment | High-throughput production of polymer-coated nanocrystals for biomedicine |

| Polymer Coating (e.g., PLGA) | Tunable based on polymer molecular weight | Enhanced biocompatibility, drug loading capability | Potential for increased hydrodynamic size | Drug delivery systems, therapeutic nanocrystals |

| Ligand Exchange | Minimal size increase | Maintains near-original nanocrystal size, surface functionalization | Complex optimization of ligand chemistry | Imaging agents, sensors requiring small size |

| Phase-Transfer Catalysis | Molecular to nanoscale | Accelerates reaction kinetics in multiphase systems | Catalyst separation and recycling challenges | Synthesis of quantum dots, metallic nanocrystals |

Experimental data demonstrates that FNP achieves exceptional colloidal stability with iron oxide nanoparticle (IONP) loadings up to 43%, significantly higher than conventional methods [9]. This technique enables precise tuning of physicochemical properties exclusively through variations in the size and hydrophobicity of the starting nanocrystals. Biological compatibility assessments of FNP-generated nanoparticles show no discernible cytotoxicity in human dermal fibroblasts, highlighting their potential for therapeutic applications [9].

Advanced Separation Mechanisms for Nanocrystals

Principles and Techniques

Separation mechanisms leverage differences in nanocrystal physical properties—including size, density, magnetic susceptibility, and surface charge—to achieve precise classification and purification. Microfluidic-based separation represents a particularly advanced approach, offering superior control through the combination of multiple physical effects in miniaturized channels [13] [11]. These systems enable continuous, on-chip processing with significantly enhanced resolution compared to conventional methods.

Inertial and thermophoretic effects can be synergistically combined in three-dimensional serpentine-spiral microfluidic devices to achieve separation across micro- and nanoscales [13]. This multi-physical field approach compensates for the limitations of single-field strategies, with Dean flow-induced inertial effects and Joule heating-driven thermophoresis working in concert to sharpen separation bands and improve efficiency. The radial temperature gradients established in these devices create thermophoretic forces that direct particles toward specific equilibrium positions based on their size and surface properties [13].

Magnetic-field-assisted assembly provides another powerful separation mechanism, particularly for nanocrystals with inherent or imparted magnetic properties. This approach utilizes controlled magnetic fields to assemble nanoparticles into nanoporous structures that function as highly selective nanosieves [11]. These structures enable the efficient entrapment and separation of biological nanoparticles, including small extracellular vesicles (SEVs), based on size and magnetic responsiveness [11].

Performance Comparison of Separation Techniques

Table 2: Comparison of Nanocrystal Separation Mechanisms

| Separation Technique | Particle Size Range | Efficiency/Resolution | Throughput | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic (Inertial/Thermophoretic) | 200 nm - 5 μm | High separation sharpness, reaches nanoscale | Continuous flow, moderate throughput | Separation of live cells from nanoscale debris, nanoparticle classification |

| Magnetic-Field-Assisted Assembly | 30 nm - 200 nm | High efficiency for magnetic nanoparticles | Rapid processing (minutes) | Isolation of small extracellular vesicles, magnetic nanoparticle purification |

| Ultracentrifugation | Broad size range | Moderate, depends on density differences | Batch processing, low to moderate throughput | Conventional nanoparticle separation, laboratory scale |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography | 1 - 100 nm | High size resolution | Low to moderate throughput | Analytical separation, high-precision applications |

Experimental characterization of the three-dimensional serpentine-spiral and adjustable radial temperature (SART) device demonstrates its effectiveness in separating complex particle mixtures containing both microparticles (4.9, 3, and 1 μm) and nanoparticles (500, 380, and 200 nm) [13]. The combined inertial and thermophoretic effects not only extend separation to the nanoscale but significantly enhance band sharpness compared to single-mechanism approaches [13].

Similarly, magnetic-field-assisted nanoparticle assembly in microfluidic systems achieves efficient separation of small extracellular vesicles from minimal sample volumes (as low as 10 μL) [11]. This method constructs tailored nanoporous structures in situ through controlled magnetic assembly of Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles, creating size-based separation matrices that can be optimized for specific nanocrystal dimensions [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Flash Nanoprecipitation for Phase Transfer

Objective: Transfer hydrophobic iron oxide nanocrystals (IONPs) from organic solvent to aqueous phase with controlled hydrodynamic diameter and high colloidal stability.

Materials:

- Hydrophobic IONPs (10-30 nm) synthesized via thermal decomposition

- Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)

- Organic solvent (e.g., tetrahydrofuran)

- Aqueous buffer solution

- Flash nanoprecipitation device

Procedure:

- Dissolve hydrophobic IONPs and PLGA in organic solvent at controlled ratios to achieve target nanocrystal loading (up to 43%)

- Prepare aqueous buffer solution for the receiving phase

- Utilize FNP device with confined impingement jet mixers to achieve rapid mixing of organic and aqueous streams

- Control flow rates to maintain turbulent mixing conditions with Reynolds number >2000

- Collect resulting aqueous suspension of PLGA-coated IONPs

- Purify by dialysis or tangential flow filtration to remove organic solvent residues

Characterization:

- Determine hydrodynamic diameter via dynamic light scattering (target: ~250 nm)

- Assess colloidal stability through zeta potential measurements and stability tracking over time

- Evaluate nanocrystal loading through thermogravimetric analysis or magnetic measurements

- Verify absence of cytotoxicity using human dermal fibroblast assays [9]

Microfluidic Separation Combining Inertial and Thermophoretic Effects

Objective: Separate mixed micro-/nanoparticle populations based on combined inertial and thermophoretic effects.

Materials:

- Three-dimensional serpentine-spiral microfluidic device

- Cylindrical heating rod for radial temperature gradient

- Syringe pump for precise flow control

- Particle mixture (e.g., 4.9, 3, and 1 μm microparticles + 500, 380, and 200 nm nanoparticles)

- DC power supply for Joule heating

Procedure:

- Fabricate flexible microfluidic chip with serpentine-spiral channel design

- Roll chip around cylindrical heating rod to create 3D configuration

- Introduce particle mixture into device using syringe pump at controlled flow rates (typically 0.1-1 mL/min)

- Apply electrical power (0.5-5 W) to establish radial temperature gradient (10-50°C)

- Optimize flow rate (inertial effects) and temperature gradient (thermophoresis) to achieve separation

- Collect separated fractions from different outlet channels

- Analyze separation efficiency via microscopy or flow cytometry

Characterization:

- Numerical simulation of Dean flow and temperature distribution

- Experimental optimization of separation parameters

- Efficiency quantification based on particle concentration in output streams

- Application to biological samples (e.g., separation of live cells from nanoscale debris) [13]

Visualization of Mechanisms

Phase-Transfer Process Diagram

Separation Mechanism Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Phase-Transfer and Separation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | Polymer coating for phase transfer | Biocompatible, controllable degradation rate, FDA-approved | Coating of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications [9] |

| Iron Oleate (FeOl) | Precursor for hydrophobic nanocrystals | Enables thermal decomposition synthesis, controls size | Synthesis of monodisperse IONPs (10-30 nm) [9] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Surface ligand during synthesis | Controls growth and stabilization of nanocrystals | Size control agent in thermal decomposition [9] |

| Fe₃O₄ Magnetic Nanoparticles | Separation agents and components | Responsive to magnetic fields, tunable surface chemistry | Formation of nanoporous assemblies for microfluidic separation [11] |

| Quaternary Ammonium Salts | Phase-transfer catalysts | Shuttle reactants across immiscible phases | Catalysts in oxidative processes [12] |

| Microfluidic Chips (3D Serpentine-Spiral) | Separation platforms | Combine multiple physical effects, high resolution | SART devices for inertial/thermophoretic separation [13] |

Phase-transfer and separation mechanisms represent complementary yet distinct critical processes in nanocrystal synthesis and purification. Flash nanoprecipitation emerges as a superior phase-transfer strategy for achieving controlled hydrodynamic sizes and high nanocrystal loadings, while combined inertial-thermophoretic microfluidics offers exceptional resolution for separating complex nanoparticle mixtures. The selection of appropriate methodologies depends fundamentally on the target nanoparticle characteristics and intended applications, with biomedical implementations prioritizing biocompatibility and colloidal stability.

Future developments will likely focus on integrating these mechanisms into continuous-flow systems, enhancing process sustainability, and employing machine learning for parameter optimization [10]. As nanocrystal applications expand in drug delivery, diagnostics, and electronic devices, precise control over phase-transfer and separation processes will remain essential for translating laboratory syntheses into commercially viable and clinically applicable nanomaterials.

The field of nanocrystal synthesis has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from traditional organometallic approaches toward greener methodologies guided by the principles of Green Chemistry. This shift represents a fundamental change in chemical philosophy, moving from a primary focus on performance and efficiency to a more holistic framework that prioritizes environmental impact, safety, and sustainability throughout the research and development lifecycle [14]. The 12 principles of Green Chemistry, first postulated by Paul Anastas and John Warner in the 1990s, provide the foundational framework for this evolution, emphasizing the minimization or non-use of toxic solvents and the non-generation of hazardous waste [14]. This review objectively compares these synthetic paradigms within nanocrystal research, examining their operational parameters, environmental footprints, and performance characteristics to provide researchers with a comprehensive guide for methodological selection.

Historical Context and Philosophical Evolution

The growing process of industrialization served as a milestone for world economic evolution but simultaneously created significant environmental challenges. By the 1940s, environmental issues began emerging in relation to industrial activities, though government policies remained largely disconnected from these impacts [14]. The contemporary environmental movement gained momentum in the 1960s with the publication of "Silent Spring," which raised ecological awareness and stimulated government initiatives [14]. This environmental consciousness continued developing through landmark events including the 1972 Stockholm Conference, the Brundtland Report's definition of sustainable development in 1987, and the Earth Summit in 1992 [14].

Within this context, the chemical industry faced particular scrutiny. A 1994 survey by the European Chemical Industry Council revealed generally unfavorable public views, with most interviewees不相信化学工业关注可持续发展行动 [14]. This perception, coupled with regulatory pressures, stimulated a fundamental reexamination of chemical practices. The formalization of Green Chemistry as a discipline emerged through key developments including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's 1991 program on alternative synthetic routes for pollution prevention, the 1995 Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge program, and the 1997 establishment of the Green Chemistry Institute [14]. The philosophical shift from pollution control to pollution prevention represented a critical turning point, with Green Chemistry providing "a framework for chemists and chemical engineers to do their part in contributing to the broad scope of global sustainability" [15].

Comparison of Synthetic Methodologies

Traditional Organometallic Routes

Traditional organometallic approaches have historically dominated high-quality nanocrystal synthesis, particularly for semiconductor quantum dots and metal nanocrystals. These methods typically involve high-temperature decomposition of organometallic precursors in high-boiling-point organic solvents. The synthesis of metal nanocrystals via these routes has provided "mechanistic insights into NC formation" that "translated into precision control over NC size, shape, and composition" [16].

Key Characteristics:

- Precursors: Metal carbonyls, alkylmetals, and other organometallic compounds

- Solvents: High-boiling-point organic solvents (e.g., octadecene, phenyl ether)

- Conditions: High temperatures (200-350°C), inert atmosphere

- Ligands: Long-chain alkyl amines, acids, and phosphines for surface stabilization

While these methods yield nanocrystals with excellent size distribution, crystallinity, and optical properties, they present significant environmental and safety concerns. Many precursors are pyrophoric, air-sensitive, and highly toxic, requiring specialized handling and generating hazardous waste [14] [2]. The solvents employed are frequently volatile organic compounds with substantial environmental footprints, and the high energy inputs required contribute to poor process atom economy.

Green Chemistry Approaches

Green Chemistry methodologies have emerged as sustainable alternatives, aligning with the 12 principles that emphasize waste prevention, safer solvents, and renewable feedstocks [14]. These approaches include biological synthesis using microorganisms, plant extracts, or enzymes, as well as solvent-free mechanochemical methods and aqueous-based routes [2].

Key Characteristics:

- Precursors: Inorganic salts, biogenic sources, and less hazardous compounds

- Solvents: Water, ionic liquids, or bio-based solvents

- Conditions: Often milder temperatures, ambient to moderate pressure

- Ligands: Biomolecules, citrate, or other benign capping agents

A prominent example in silicon nanocrystal (SiNC) synthesis demonstrates the green chemistry evolution. Researchers have developed methods using hydrogen silsesquioxane (HSQ) polymers derived from trichlorosilane, water, and methanol, systematically varying precursor ratios to control polymer structure and resulting nanocrystal properties [6]. This approach represents a shift toward "cost-effective and tunable precursors" that address the "poor shelf life, high cost, and limited supply" of commercial HSQ [6].

Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies

Table 1: Direct comparison of traditional organometallic and green chemistry approaches for nanocrystal synthesis

| Parameter | Traditional Organometallic Routes | Green Chemistry Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Toxicity | High (pyrophoric, air-sensitive) [2] | Low to moderate (aqueous salts, biogenic) [2] |

| Solvent Environmental Impact | High (VOCs, halogenated) [14] | Low (water, ionic liquids) [14] [15] |

| Energy Input | High (200-350°C) [16] | Variable (ambient to moderate) [2] |

| Atomic Economy | Moderate to poor [14] | Good to excellent [15] |

| Waste Generation | Significant hazardous waste [14] | Minimal, often biodegradable [2] |

| Size Control | Excellent (1-5% size dispersion) [16] | Moderate to good (5-15% size dispersion) [6] [2] |

| Crystallinity | Excellent [16] | Variable [6] [2] |

| Scalability | Established for industrial scale [16] | Emerging, with promising hybrid approaches [2] |

| Representative Quantum Yield | 80-95% (CdSe QDs) [16] | 3-10% (SiNCs, green routes) [6] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Traditional Organometallic Synthesis of Quantum Dots

Protocol based on established organometallic routes [16]:

- Setup: Three-neck flask equipped with thermometer, condenser, and septum, under inert atmosphere

- Precursor Preparation: 0.4 mmol cadmium oxide (CdO), 4 mmol stearic acid, and 20 mL octadecene

- Reaction Mixture: Heat to 150°C under N₂ until clear solution forms, then cool to 100°C

- Selenium Stock: Quickly inject 2 mL trioctylphosphine containing 0.8 mmol selenium powder

- Nanocrystal Growth: Heat to 250-320°C for nucleation and growth monitoring

- Purification: Cool to 60°C, add anhydrous ethanol, centrifuge at 4000 rpm for 5 minutes

- Redispersion: Disperse precipitate in hexane or toluene for characterization

Key Parameters: Temperature control critical for size distribution; precursor reactivity determines nucleation kinetics; ligand concentration affects growth rate and final size.

Green Synthesis of Silicon Nanocrystals from Silsesquioxane Polymers

Protocol based on response surface methodology optimization [6]:

Polymer Precursor Synthesis:

- Molar ratios varied systematically using Scheffé's polynomial model (trichlorosilane:water:methanol)

- Rapid addition of methanol to trichlorosilane under argon atmosphere

- Immediate injection of water to initiate hydrolysis and condensation

- Reaction proceeds at room temperature with stirring for 24 hours

- Dry polymer precursors characterized by FTIR spectroscopy

Nanocrystal Formation:

- Pyrolysis of synthesized polymers at 1100°C under forming gas (95%/5% N₂/H₂)

- Etch silica matrix with hydrofluoric acid to liberate hydride-terminated SiNCs

- Surface passivation via thermal hydrosilylation with 1-dodecene at 180°C for 2 hours

Characterization:

- FTIR analysis of cage vs. network structures in polymer precursors

- XRD for nanocrystal size and crystallinity

- Photoluminescence spectroscopy for quantum yield measurement

Key Findings: "Higher proportions of methanol and water in a trichlorosilane:water:methanol mixture result in larger amounts of network-type polymer structures" which "yield silicon nanocrystals with higher photoluminescence quantum yields" though "factors other than precursor structure play significant roles" [6].

Machine Learning-Assisted Optimization

Emerging approaches leverage statistical design and machine learning to accelerate green method development. Response surface methodology (RSM) has been successfully applied to "quantitatively model the relationship between precursor molar ratios, polymer structure (cage vs. network content), and photoluminescence quantum yield" [6]. Similarly, machine learning models using K-Nearest Neighbors classifiers have achieved 95% accuracy in predicting the crystalline nature of cellulose nanocrystals based on source and reaction conditions, effectively "bypassing the need for trial-and-error synthesis" [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for nanocrystal synthesis across methodological approaches

| Reagent/Material | Function | Traditional Routes | Green Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Provide elemental composition | Metal carbonyls, alkylmetals [16] | Inorganic salts, biogenic extracts [2] |

| Solvent Medium | Reaction environment | Octadecene, phenyl ether [16] | Water, ionic liquids, supercritical CO₂ [15] |

| Stabilizing Agents | Control growth and prevent aggregation | Trioctylphosphine, alkyl amines [16] | Citrate, starch, chitosan [2] |

| Reducing Agents | Convert precursors to elemental form | Diisobutylaluminum hydride, superhydride [16] | Ascorbic acid, plant phenols [2] |

| Capping Ligands | Surface passivation and functionality | Thiols, phosphines, phosphine oxides [16] | Glutathione, amino acids, oligonucleotides [2] |

| Structure-Directing Agents | Control morphology and crystal facet expression | Halide ions, specific surfactant mixtures [16] | Biomolecules with specific binding motifs [2] |

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Optical Properties and Quantum Yield

The photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) represents a critical performance metric for nanocrystals, particularly in applications such as bioimaging, displays, and quantum technologies. Traditional organometallic routes to semiconductor quantum dots consistently achieve PLQY values of 80-95% for materials like CdSe/CdS core/shell structures [16]. These high values result from precise surface passivation and excellent crystallinity afforded by high-temperature synthesis.

In comparison, green-synthesized nanocrystals typically exhibit more variable performance. Alkyl-passivated silicon nanocrystals derived from silsesquioxane polymers show PLQY values ranging from approximately 3% to 10%, with emission peaks between 636 nm and 689 nm [6]. Statistical modeling of these systems reveals that "higher PLQY was associated with lower cage:network ratios" in the polymer precursors, though "the correlation is weaker than that observed between precursor ratios and polymer structure" [6].

Structural Characteristics and Crystallinity

X-ray diffraction analysis provides quantitative data on nanocrystal size, phase, and crystallinity. Traditional organometallic methods typically produce nanocrystals with well-defined crystal phases, narrow size distributions (relative standard deviation <5%), and high crystallinity evidenced by sharp diffraction peaks [16].

Green-synthesized nanocrystals exhibit greater structural diversity. In the case of silicon nanocrystals from silsesquioxane precursors, XRD analysis revealed that "polymer precursors made without adding methanol yielded larger nanocrystals whereas the addition of both water and methanol resulted in smaller sizes" [6]. Similar variability appears in cellulose nanocrystals, where crystallinity index—predicted with high accuracy (R² = 0.82) using machine learning models—strongly depends on cellulose source and processing history [17].

Table 3: Experimental performance data for representative nanocrystal systems

| Nanocrystal System | Synthesis Method | Size Range (nm) | Size Distribution (%) | Quantum Yield (%) | Crystallinity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CdSe QDs | Organometallic [16] | 2-8 | 3-5 | 80-95 | High |

| SiNCs | HSQ Pyrolysis [6] | 3-90 | 10-20 | 3-10 | Moderate-High |

| Cellulose NCs | Acid hydrolysis [17] | 5-20 | 15-30 | N/A | Variable |

| Metal NCs (Au, Ag) | Biological [2] | 5-50 | 15-25 | N/A | Moderate |

Visualization of Methodological Evolution and Workflows

Diagram 1: Evolution from traditional organometallic to green chemistry approaches in nanocrystal synthesis, highlighting key methodological differences and trade-offs.

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The evolution from organometallic routes to Green Chemistry in nanocrystal synthesis reflects a broader paradigm shift in materials science—from resource-driven to ecology-driven approaches [18]. This transition aligns with global sustainability initiatives and the circular economy model, where the design of chemical products and processes explicitly considers environmental impact across the entire lifecycle [15].

Future research directions will likely focus on bridging the performance gap between traditional and green methods while further reducing environmental footprints. Emerging areas include:

- Hybrid approaches that integrate the precision of organometallic chemistry with the sustainability of green principles [2]

- Advanced computational guidance using machine learning and response surface methodology to optimize complex multi-parameter syntheses [6] [17]

- Revolutionary catalysis routes for green energy and chemical production that utilize abundant resources like "sunshine, water, and carbon dioxide" [18]

The quantitative comparisons presented in this review enable researchers to make informed decisions based on both performance requirements and sustainability considerations. While traditional organometallic routes currently offer superior control and optical properties, green chemistry approaches provide compelling advantages in safety, environmental impact, and alignment with sustainable development goals. As green methodologies continue maturing, their integration with traditional expertise will likely yield increasingly sophisticated nanocrystal synthesis platforms that do not force a choice between performance and planetary health.

Autonomous laboratories, often called "self-driving labs," represent a fundamental shift in scientific research. By integrating artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and automated workflows, these labs can propose, execute, and analyze experiments with minimal human intervention. This new paradigm is poised to dramatically accelerate the discovery and optimization of new materials and chemicals, including nanocrystals, by navigating vast experimental parameter spaces with unprecedented speed and precision [19] [20] [21].

The Core Engine of Autonomous Labs

An autonomous laboratory functions as a cohesive system built on several interdependent pillars that replace traditional manual processes.

The Foundational Elements

The operation of a self-driving lab relies on the seamless integration of four key components [19]:

- Chemical Science Databases: These serve as the knowledge base, aggregating and structuring data from literature, patents, and previous experiments. They are often built using natural language processing (NLP) to extract information from text and images, forming a structured resource for AI planning [19].

- Large-Scale Intelligent Models: AI algorithms are the "brain" of the operation. They use data from the knowledge base and ongoing experiments to predict outcomes and decide which experiments to run next. Common algorithms include Bayesian optimization, genetic algorithms, and the A* algorithm, each with strengths in navigating complex, multi-dimensional search spaces [19] [22].

- Automated Experimental Platforms: This is the physical layer of the lab, comprising robotic arms, liquid handlers, reactors, and characterization instruments. These robots execute the physical tasks of synthesis, sampling, and measurement, ensuring 24/7 operation and high reproducibility [23] [22].

- Management and Decision Systems: This is the central software that orchestrates the entire closed-loop process, connecting the AI's decisions to the robotic hardware and managing the data flow from characterization back to the AI for the next decision [19].

The Closed-Loop Workflow

These elements work together in a continuous "predict-make-measure-analyze" cycle [19]. The AI model proposes an experiment to achieve a researcher-defined goal. A robotic platform automatically synthesizes the target material, such as nanocrystals. Integrated instruments then characterize the product's properties. The resulting data is fed back to the AI model, which refines its understanding and proposes the next experiment, creating a tight loop of accelerated learning and optimization [22] [24].

Performance Comparison: Autonomous Labs vs. Traditional Methods

The quantitative advantage of autonomous laboratories is evident in their ability to achieve research objectives in a fraction of the time and with far greater data efficiency than traditional manual approaches.

Direct Comparisons in Nanocrystal Synthesis

Recent studies directly comparing autonomous and traditional methods for nanocrystal synthesis highlight significant performance gains.

| Platform/Method | Material Optimized | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI-powered Dynamic Flow Lab [20] | Inorganic Materials | Data Collection Rate | 10x more data than steady-state self-driving labs |

| A* Algorithm Platform [22] | Au Nanorods (Multi-target) | Experiments to Convergence | 735 experiments |

| A* Algorithm Platform [22] | Au Nanospheres / Ag Nanocubes | Experiments to Convergence | 50 experiments |

| Rainbow SDL [24] | Metal Halide Perovskite NCs | Acceleration Factor | 10x to 100x acceleration over status quo |

Algorithm Efficiency in Autonomous Experimentation

The choice of AI algorithm critically impacts how quickly an autonomous lab can find an optimal solution. Research demonstrates that some algorithms are better suited for specific types of search spaces.

| Algorithm | Reported Application | Performance Notes | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| A* Algorithm [22] | Optimization of Au nanorods, nanospheres, and Ag nanocubes | Outperformed Optuna and Olympus in search efficiency, requiring fewer iterations | Heuristic search efficient for discrete parameter spaces |

| Bayesian Optimization [19] [24] | Optimization of photocatalysts, thin-film materials, and metal halide perovskite NCs | Efficiently minimizes the number of trials needed for convergence | Effective for balancing exploration and exploitation |

| Genetic Algorithms (GA) [19] | Optimization of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and Au nanomaterials | Effective for handling large numbers of variables; uses an evolutionary approach | Suitable for complex, multi-parameter optimization |

Experimental Protocols in Autonomous Nanocrystal Synthesis

The following protocols detail the specific methodologies used by leading autonomous laboratories, showcasing the practical application of the principles and technologies described above.

Protocol 1: Multi-Target Nanoparticle Synthesis using a GPT and A* Driven Platform

This protocol from a 2025 Nature Communications study outlines an end-to-end automated system for synthesizing various metallic nanoparticles [22].

- 1. Literature Mining & Initial Method Generation: A Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) model queries a database of scientific literature to retrieve established synthesis methods and parameters for the target nanomaterial (e.g., Au, Ag, Cu₂O) [22].

- 2. Automated Script Generation: The experimental steps generated by the GPT model are translated into an automated operation script (mth or pzm files). This script directly controls the robotic hardware [22].

- 3. Robotic Synthesis Execution: A "Prep and Load" (PAL) system performs the synthesis. The platform includes:

- Z-axis robotic arms for liquid handling and transferring reaction bottles.

- Agitators for mixing solutions.

- A centrifuge module for product purification.

- A fast wash module for cleaning equipment [22].

- 4. In-line Characterization: The synthesized nanoparticles are automatically transferred to a UV-Vis spectrometer for immediate optical characterization [22].

- 5. AI-Driven Optimization Loop: The characterization data (e.g., LSPR peak, FWHM) and synthesis parameters are fed to the A* algorithm. The algorithm calculates and proposes the next set of parameters to improve the outcome, and the process repeats from step 3 until the target properties are met [22].

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Metal Halide Perovskite NC Optimization using a Multi-Robot Platform (Rainbow)

This protocol, from a 2025 Nature Communications paper, focuses on the "Rainbow" platform, which is specialized for optimizing metal halide perovskite nanocrystals (MHP NCs) [24].

- 1. Precursor Preparation: A liquid handling robot prepares NC precursors in parallelized, miniaturized batch reactors. This setup is ideal for handling both continuous and discrete parameters, such as different ligand structures [24].

- 2. Robotic Synthesis and Sampling: The liquid handler also performs multi-step NC synthesis, including post-synthesis halide exchange reactions. It automatically samples the resulting NC solutions for characterization [24].

- 3. Automated Optical Characterization: A characterization robot transfers the samples to a benchtop instrument that acquires UV-Vis absorption and photoluminescence (PL) emission spectra. This provides key performance metrics: Peak Emission Energy (EP), Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY), and Emission Linewidth (FWHM) [24].

- 4. Multi-Objective AI Decision Making: A machine learning agent, often using Bayesian optimization, analyzes the spectral data. The AI's goal is to simultaneously optimize multiple objectives (e.g., maximize PLQY and minimize FWHM at a target emission energy). It then proposes a new set of synthesis conditions for the next iteration [24].

- 5. Pareto-Optimal Formulation Identification: The closed-loop cycle continues until the platform identifies Pareto-optimal formulations—representing the best possible trade-offs between the competing target properties [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The functionality of autonomous labs depends on a suite of physical and digital tools. The table below catalogues essential "reagent solutions" central to the operation of platforms like those described in the experimental protocols.

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Autonomous Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Large Language Models (LLMs) / GPT [22] | Serves as a knowledge retrieval engine, parsing scientific literature to suggest initial synthesis methods and parameters based on natural language queries. |

| A* Algorithm [22] | Functions as a heuristic search algorithm to efficiently navigate discrete synthesis parameter spaces, optimizing for target nanomaterial properties with fewer experiments. |

| Bayesian Optimization [19] [24] | Acts as a surrogate model-based AI agent for managing the exploration-exploitation trade-off, efficiently guiding experiments toward optimal conditions in a continuous parameter space. |

| Liquid Handling Robot [22] [24] | The core actuator for liquid transfer, precursor preparation, and sample manipulation, ensuring high reproducibility and enabling complex, multi-step synthesis protocols. |

| Parallelized Miniaturized Batch Reactors [24] | Provide a versatile platform for conducting numerous small-scale synthesis reactions simultaneously, ideal for screening discrete variables like ligand type. |

| In-line UV-Vis Spectrophotometer [22] | An automated characterization tool that provides immediate feedback on nanoparticle optical properties (e.g., LSPR peak, absorbance), which is essential for the closed-loop decision cycle. |

| Photoluminescence (PL) Spectrometer [24] | A key characterization instrument for semiconductor nanocrystals, used to automatically measure critical performance metrics like Peak Emission Energy, PLQY, and FWHM. |

| Organic Acid/Base Ligands [24] | Key molecular reagents that control the surface chemistry, growth, stabilization, and final optical properties of colloidal nanocrystals during synthesis. |

The controlled synthesis of nanocrystals is a cornerstone of modern nanotechnology, with precise control over yield, size, crystallinity, and surface properties being critical for applications ranging from drug delivery to optoelectronics. The synthesis output dictates the nanocrystals' performance in subsequent applications, making the understanding and optimization of these parameters a primary research focus. This guide provides a comparative analysis of major nanocrystal synthesis methodologies, highlighting how different approaches—chemical, biological, and physical—influence these key output targets. By objectively comparing experimental data and protocols, this work serves as a reference for researchers and scientists in selecting and optimizing synthesis routes for specific application requirements, framed within the broader context of nanocrystal synthesis method comparison and yield research.

Comparative Analysis of Synthesis Methods and Outputs

The selection of a synthesis method directly determines the characteristics of the resulting nanocrystals. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of the key performance indicators for different synthesis approaches.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Nanocrystal Synthesis Methods and Key Outputs

| Synthesis Method | Typical Yield Range | Size Control & Range | Crystallinity | Key Surface Properties | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot-Injection (for Semiconductors) | Information missing | Excellent control; ~2–10 nm [25] | High, single crystals [26] | Coated with organic amphiphiles (e.g., TOPO) [26] | Optoelectronics, photovoltaics, quantum dots [16] [25] |

| Acid Hydrolysis (for CNCs) | 7%-40% (varies by source) [27] [28] | Rod-like, 3–20 nm diameter, 100–500 nm length [29] [27] | High crystallinity [29] | Sulfate esters (H₂SO₄) impart negative charge [28] | Biomedicine, composites, rheology modifiers [29] [27] |

| Organic Acid Hydrolysis (for CNCs) | ~55% (can exceed H₂SO₄ yield) [28] | Rod-like, dimensions comparable to conventional CNC [28] | High crystallinity index (e.g., ~79%) [28] | Carboxylation (e.g., with oxalic acid) [28] | Sustainable materials, green chemistry [28] |

| Nanoprecipitation | Information missing | Good control; few nm to µm [30] | Can produce various nanocrystals [30] | Can be surfactant-free; surface depends on solute/solvent [30] | Drug delivery, polymer nanoparticles, semiconductors [30] |

| Biological Synthesis | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing | Depends on biological template (e.g., microorganisms) [2] | Green synthesis, sustainable nanotechnology [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

Hot-Injection Synthesis of PbS Quantum Dots

Principle: This method involves rapid injection of precursors into a hot coordinating solvent, leading to instantaneous nucleation followed by controlled growth [25].

- Key Reagents:

- Metal Precursor: Lead oleate (Pb(OA)₂) in 1-octadecene (ODE).

- Chalcogenide Precursor: Bis(trimethylsilyl) sulfide ((TMS)₂S).

- Solvent/Ligand: 1-Octadecene (ODE) and oleic acid (HOA) [25].

- Detailed Procedure:

- The metal precursor solution (Pb(OA)₂ in ODE with HOA ligand) is loaded into a three-neck flask with a condenser and heated to the target nucleation temperature (e.g., 100-160°C) under inert atmosphere and stirring.

- The chalcogenide precursor ((TMS)₂S) is swiftly injected into the hot solution.

- Immediate nucleation occurs, and the temperature drops. The reaction is then maintained at a lower temperature for growth or subjected to specific temperature plateau manipulations to control size and size distribution [25].

- Growth is halted by removing the heating source and cooling the reaction mixture.

- Purification is achieved through centrifugation and repeated washing with anti-solvents like acetone or ethanol [25].

Acid Hydrolysis for Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNCs)

Principle: Strong acids selectively hydrolyze and remove the amorphous regions of cellulose microfibrils, releasing rigid, crystalline nanocrystals [29] [28].

- Key Reagents:

- Detailed Procedure:

- The cellulose source is treated with concentrated sulfuric acid at 40-70°C for 30-60 minutes under vigorous stirring. The acid-to-cellulose ratio is critical.

- The reaction is quenched by adding a large excess of cold deionized water.

- The resulting suspension is purified via repeated centrifugation (e.g., 8000-10000 rpm) to remove acid and reaction by-products.

- The suspension is dialyzed against deionized water until the effluent reaches a neutral pH.

- Finally, the suspension is dispersed using sonication (e.g., probe sonicator at 300 W for 10 minutes) to individualize the CNCs [28].

Green Hydrolysis for CNCs using Organic Acids

Principle: Environmentally friendly organic acids (e.g., citric, formic, oxalic) hydrolyze amorphous cellulose, often with simultaneous surface functionalization [28].

- Key Reagents:

- Cellulose Source: As above.

- Acid: Formic acid (FA, 65-80% w/w) or oxalic acid (OA) [28].

- Detailed Procedure:

- Cellulose is reacted with concentrated formic acid at reflux temperature for several hours.

- The mixture is cooled and centrifuged (e.g., 8000 rpm for 5 min). The sediment is washed with deionized water multiple times via centrifugation.

- The collected sediment is dialyzed against deionized water until neutral pH is achieved.

- The suspension is sonicated and then centrifuged at a lower speed (e.g., 3000 rpm for 3 min) to separate the CNC supernatant from larger aggregates [28].

Nanoprecipitation

Principle: A solute dissolved in a solvent is rapidly mixed with an anti-solvent, causing a decrease in solvent quality and leading to spontaneous nucleation and formation of nanoparticles [30].

- Key Reagents:

- Solute: Polymers, small organic molecules, or semiconductors.

- Solvent: Water-miscible organic solvent (e.g., acetone, ethanol).

- Anti-solvent: Water or an aqueous solution.

- Detailed Procedure:

- The solute is dissolved in the organic solvent.

- This solution is rapidly mixed with the anti-solvent (water) under controlled conditions (e.g., using magnetic stirring, flash mixing, or microfluidic devices). The mixing dynamics are critical for controlling size and distribution [30].

- The organic solvent is removed, often by evaporation, leaving the nanoparticles dispersed in the aqueous phase.

- Surfactants or stabilizers can be added to the anti-solvent to control surface properties and prevent aggregation [30].

Synthesis Workflows and Kinetic Pathways

Hot-Injection Synthesis Workflow

Diagram 1: Hot-injection synthesis workflow.

CNC Acid Hydrolysis Workflow

Diagram 2: CNC acid hydrolysis workflow.

Nanocrystal Formation Kinetics

The synthesis of colloidal nanocrystals like PbS CQDs follows a multi-stage kinetic pathway, as described by the Improved Kinetic Rate Equation (IKRE) model [25].

Diagram 3: Nanocrystal formation kinetics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table details essential reagents and their functions in nanocrystal synthesis, as derived from the cited experimental protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions in Nanocrystal Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Precursors | Lead Oleate (Pb(OA)₂), Bis(trimethylsilyl) sulfide ((TMS)₂S) [25] | Source of metal and chalcogenide ions for semiconductor quantum dot formation. |

| Coordinating Solvents/ Ligands | Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO), Oleic Acid (HOA) [26] [25] | Coordinate metal ions, control growth, passivate surface, and provide colloidal stability. |

| Mineral Acids | Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄) [28] | Hydrolyzes glycosidic bonds in cellulose, preferentially attacking amorphous regions to release CNCs. |

| Organic Acids | Formic Acid (FA), Oxalic Acid (OA) [28] | Green alternative for CNC hydrolysis; can introduce carboxyl groups for better dispersion. |

| Solvents & Anti-Solvents | 1-Octadecene (ODE), Acetone, Water [25] [30] | ODE: High-booint solvent for hot-injection. Acetone/Water: Anti-solvent for nanoprecipitation and purification. |

| Cellulose Sources | Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC), Wood Pulp, Sugarcane Bagasse [27] [28] | Renewable raw material for the top-down production of cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs). |

A Method-by-Method Breakdown: Techniques, Protocols, and Use Cases

Solution-phase synthesis is a foundational method for producing metallic and semiconductor nanocrystals (NCs), enabling precise control over their size, shape, and composition. This guide objectively compares its performance against other prevalent synthesis methods, supported by experimental data, to inform selection for research and development.

Method Comparison at a Glance

The table below compares solution-phase synthesis with other common nanocrystal synthesis methods across key performance metrics.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Nanocrystal Synthesis Methods

| Synthesis Method | Typical NC Products | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations | Sample Crystallinity & Phase Purity | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solution-Phase Synthesis | Metal NCs (Au, Ag), Alkaline earth polysulfides, Multielement alloys [31] [32] [33] | Low energy requirement, exquisite size & shape control, high compositional tunability [31] [33] | Ligand removal challenges, solvent use [32] | High (e.g., pure BaS₂, SrS₂, intermetallic phases) [31] [32] | High (batch reactors) to Moderate (complex workflows) [34] |

| Mechanochemical Synthesis | Regenerated chemicals (e.g., NaBH₄), composite materials [35] | Solvent-free, simple operation, often high yield [35] | Reproducibility and scale-up challenges, parameter complexity [35] | Variable (can be high, but sensitive to milling conditions) [35] | Moderate (challenges in process transfer) [35] |

| Solid-State Synthesis | Multicomponent oxides (e.g., battery cathodes), LnCuOSe bulk materials [36] [37] | High-temperature stability, access to complex phases [36] | High energy demand, irregular morphology, by-product formation [36] | High, but often with impurity phases [36] | High |

| Vapor-Phase Deposition | Thin films, 2D materials | High purity, excellent film uniformity | Capital-intensive equipment, limited throughput, high vacuum needed | Very High | Low to Moderate |

Quantitative Performance Data

Experimental data from recent studies highlights the specific outcomes achievable with optimized solution-phase synthesis.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data for Solution-Phase Synthesized NCs

| Nanocrystal Type | Key Synthesis Parameters | Experimental Outcome & Yield | Reported Bandgap or Application Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaline Earth Polysulfides (BaS₂, SrS₂) [31] | Reaction temperature (120-200°C), Metal:S ratio (1:12), in oleylamine [31] | Selective formation of BaS₂/BaS₃ controlled by temperature; new SrS₂ polymorph [31] | Bandgaps of 2.4 - 3.0 eV (wide-bandgap semiconductors) [31] |

| Multimetallic Nanoparticles (e.g., PtM, PdM) [32] | Co-reduction with superhydride/polyalcohol/borane agents in surfactants (e.g., oleylamine) [32] | Solid-solution alloys with sizes down to ~4 nm; precise composition control [32] | Enhanced efficiency in ORR, FAO, and MOR electrocatalysis [32] |

| Metal Nanoclusters (Au, Ag, Cu) [33] | Microwave-assisted (850W, 20-30 min), GSH/Histidine ligands [33] | High quantum yield (e.g., 9.9% for AuNCs, 17% for CuNCs); ultra-small size (<3 nm) [33] | Strong photoluminescence; applications in bio-imaging and sensing [33] |

| LnCuOSe Intergrowth NCs [37] | Hot-injection of Ln-DIP complex into Cu₂Se at 320°C [37] | Anisotropic "nanoflower" morphology; successful with 6 lanthanides [37] | Wide bandgap semiconductors; evidence of quantum confinement [37] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Alkaline Earth Polysulfide NCs

This protocol describes the synthesis of wide-bandgap semiconductor NCs like BaS₂ and SrS₂ [31].

Key Reagents & Setup:

- Metal Precursors: Dried barium acetylacetonate hydrate (Ba(acac)₂·xH₂O) or strontium acetylacetonate hydrate (Sr(acac)₂·xH₂O).

- Sulfur Source: Elemental sulfur (S) flakes.

- Solvent/Ligand: Anhydrous and distilled oleylamine.

- Atmosphere: Inert N₂ glovebox.

- Molar Ratio: Metal:S = 1:12.

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Combine 0.25 mmol of the dried AE metal salt with 3 mmol of sulfur flakes in 3 mL of dried oleylamine within a borosilicate microwave vial [31].

- Reaction Execution: Heat the mixture with stirring. Temperature is a critical control parameter: higher temperatures (e.g., ~200°C) favor disulfides (BaS₂, SrS₂), while lower temperatures (e.g., ~120°C) favor trisulfides (BaS₃) [31].

- Purification: After reaction, precipitate NCs using a polar anti-solvent (e.g., ethanol) and isolate via centrifugation.

- Characterization: UV-Vis spectroscopy for bandgap estimation; TEM for size/morphology; XRD for phase identification [31].

Protocol 2: One-Pot Synthesis of Five-Fold Twinned Noble Metal NCs

This method produces noble metal nanocrystals (Au, Ag, Pd) with unique decahedral structures for catalytic and optical applications [38].

Key Reagents & Setup:

- Metal Precursor: e.g., Chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄) for gold.

- Reducing Agent: e.g., Ascorbic acid.

- Shape-Directing Agent: e.g., Silver nitrate (AgNO₃).

- Surfactant: e.g., Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB).

- Seeds: Small gold nanoparticle seeds (~5 nm).

Procedure:

- Seed Preparation: Synthesize spherical Au seed NCs by reducing a gold salt with a strong reducing agent (e.g., sodium borohydride) in the presence of a surfactant like CTAB [38].

- Growth Solution Preparation: Create a solution containing additional metal precursor, a weak reducing agent (ascorbic acid), the shape-directing agent (AgNO₃), and surfactant [38].

- Seeded Growth: Introduce the pre-formed seeds into the growth solution. The seeds act as nuclei for the asymmetric deposition of metal atoms, guided by the selective facet binding of the Ag⁺ ions, leading to the formation of penta-twinned structures like nanodecahedra or nanorods [38].

- Purification & Characterization: Purify via centrifugation. Characterize using TEM and SAED to confirm the five-fold twin structure [38].

Synthesis Workflow and Optimization

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for a solution-phase synthesis of nanocrystals, integrating both thermodynamic and kinetic control strategies.

Diagram 1: Solution-phase synthesis workflow. The process involves sequential stages from precursor preparation to final product characterization. Thermodynamic (e.g., temperature) and kinetic (e.g., precursor reactivity) factors provide critical control over nucleation and growth [31] [32] [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit

This table details essential reagents and their functions in a typical solution-phase synthesis of metallic and semiconductor NCs.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Solution-Phase Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Metal acetylacetonates (e.g., Ba(acac)₂, Sr(acac)₂), Metal halides (e.g., CuI, FeCl₂), Chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄) [31] [32] [37] | Source of metal cations; determines reduction potential and reaction kinetics [32] |

| Chalcogen Sources | Elemental Sulfur (S₈), Selenium-diphenylphosphine complexes (e.g., DIP), Trioctylphosphine Selenide (TOP-Se) [31] [37] | Reactive source of S/Se/Te anions; precursor reactivity dictates nucleation behavior [31] [37] |

| Solvents & Ligands | Oleylamine (OLA), Oleic Acid (OAc), Trioctylphosphine (TOP) [31] [32] | Solvent medium and surface capping agent; controls NC growth, dispersion, and morphology [31] [32] |

| Reducing Agents | Superhydride (LiBEt₃H), Borane tert-butylamine, Ascorbic Acid, Oleylamine itself [32] [38] | Converts metal precursors to zero-valent atoms; strength influences nucleation rate [32] |

| Shape-Directing Agents | Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃), Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) [38] | Selective adsorption on specific crystal facets to promote anisotropic growth (rods, decahedra) [38] |

Solution-phase synthesis remains the workhorse for nanocrystal fabrication due to its unparalleled control over critical parameters. The choice of synthesis method ultimately depends on the target application's requirements for crystallinity, composition, morphology, and scalability.

The synthesis of silicon nanocrystals (SiNCs) has emerged as a critical frontier in nanomaterials research, driven by their unique photoluminescent properties, terrestrial abundance, and compatibility with existing semiconductor technologies. Unlike bulk silicon, which suffers from an indirect bandgap that limits its photonic applications, silicon nanocrystals exhibit intense, tunable photoluminescence due to quantum confinement effects, making them appealing alternatives to III-V and II-VI quantum dots for applications ranging from integrated photonics to biological imaging [6]. The quest for high-yield production methods has led to the development of diverse synthetic approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations in terms of scalability, size control, and optical properties.

Among the various fabrication methodologies, non-thermal plasma (NTP) synthesis has gained significant attention as a versatile approach for producing high-quality SiNCs with controlled properties. Non-thermal plasma, characterized by its non-equilibrium state where electrons carry most of the kinetic energy while ions remain at lower temperatures, enables precise material processing without the excessive heat that can compromise nanocrystal quality [39]. This advanced technique represents a paradigm shift in SiNC manufacturing, offering distinct advantages over traditional top-down and bottom-up approaches while addressing key challenges in yield, size distribution, and surface functionalization.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of non-thermal plasma synthesis with alternative methods for silicon nanocrystal production, focusing specifically on yield optimization and practical experimental considerations. Through systematic analysis of experimental data and methodologies, we aim to equip researchers with the necessary knowledge to select appropriate synthesis strategies based on their specific application requirements, whether for photonic devices, energy storage, or biomedical applications.

Silicon Nanocrystal Synthesis Methods: A Comparative Framework

Classification of Synthesis Approaches

The fabrication of silicon nanoparticles can be broadly categorized into three primary approaches: top-down, bottom-up, and reduction methods [40]. Each strategy employs distinct physical and chemical principles to achieve nanoscale dimensions, with significant implications for the resulting nanocrystal properties, production scalability, and cost-effectiveness.

Top-down approaches involve the physical or chemical breakdown of bulk silicon into nanoscale structures. Common techniques include electrochemical etching of silicon wafers using hydrofluoric acid (HF) and water mixtures, mechanical grinding via ball milling processes, and laser ablation where laser irradiation in liquid environments produces colloidal solutions [40] [41]. These methods benefit from relatively simple production processes and the use of readily available silicon sources, including recycled silicon waste from the semiconductor industry [41]. However, challenges include limited control over particle size distribution, reduced sphericity, and potential introduction of structural defects that can compromise optical properties.

Bottom-up approaches construct nanocrystals from molecular precursors through controlled nucleation and growth processes. A prominent example is the pyrolysis of silane (SiH₄) under laser or plasma heating, where gaseous precursors decompose to form silicon nanoparticles collected on substrates [40]. Additional bottom-up strategies include high-temperature pyrolysis of hydrogen silsesquioxane (HSQ) and related silsesquioxane polymers in reducing environments, yielding size-tunable nanocrystals with hydride termination [6]. These methods generally offer superior control over crystal size and morphology but often require complex equipment and face scalability challenges.

Reduction methods convert silicon compounds through chemical reduction processes. The carbothermal reduction of silica nanoparticles with carbon at high temperatures (above 2000°C) produces silicon nanoparticles, while magnesiothermic reduction using magnesium as a reducing agent operates at lower temperatures (above 650°C) [40]. These approaches can potentially lower production costs but may result in incomplete reduction, leaving unreacted silica or forming magnesium silicide as byproducts.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Silicon Nanocrystal Synthesis Methods

| Method | Precursors/Materials | Size Range | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Thermal Plasma | Silane (SiH₄) [40] | Primarily >10 nm [40] | Continuous processing, good size control, dry synthesis | High equipment cost, complex operation |

| Pyrolysis of HSQ | Hydrogen silsesquioxane (HSQ) [6] | 3-90 nm [6] | High PLQY (up to 80%), size control [6] | Poor shelf life, high cost, limited supply [6] |

| Mechanical Milling | Bulk silicon, silicon waste [40] [41] | 100-400 nm [40] | Simple process, cost-effective, uses recycled materials [41] | Broad size distribution, irregular shape, defect introduction |

| Laser Ablation | Bulk silicon [40] | Several nm and larger [40] | Spherical nanoparticles, no chemicals required | Broad size distribution, low production volume |

| Carbothermal Reduction | Silica nanoparticles, carbon [40] | 80-200 nm [40] | Lower cost compared to silane | High temperature requirement, incomplete reduction |

| Magnesiothermic Reduction | Silica nanoparticles, magnesium [40] | ~10 nm scale [40] | Lower temperature process | Unreacted silica, magnesium silicide formation |

Non-Thermal Plasma Synthesis Fundamentals

Non-thermal plasma synthesis represents a sophisticated bottom-up approach that leverages non-equilibrium plasma conditions to facilitate the decomposition of silicon-containing precursors and subsequent nanocrystal formation. In NTP systems, electrons attain high kinetic energy (1-10 eV) while the bulk gas remains near ambient temperature, creating an environment where chemical reactions can proceed without thermal damage to the resulting nanoparticles [39].

The plasma generation process typically involves applying strong electric fields across gas-filled reactors, causing electron dissociation from gas atoms and molecules. Once the breakdown voltage is exceeded, an electron avalanche occurs, creating a sustainable plasma environment rich in reactive species [39]. For silicon nanocrystal synthesis, silane (SiH₄) serves as the most common precursor gas, though other silicon-containing compounds can be utilized. The decomposition pathway involves silane dissociation through electron impact, followed by nucleation of silicon clusters that grow through surface reactions with additional silicon-bearing species.

The non-thermal nature of this process allows precise control over nucleation and growth kinetics through manipulation of plasma parameters including power density, pressure, flow rates, and reactor geometry. This control enables tuning of critical nanocrystal characteristics such as size, crystallinity, and surface chemistry, making NTP synthesis particularly valuable for applications requiring narrow size distributions and specific optical properties [40] [39].

Non-Thermal Plasma Synthesis: Experimental Protocols and Yield Optimization

Standard Non-Thermal Plasma Synthesis Procedure

The experimental setup for non-thermal plasma synthesis of silicon nanocrystals typically consists of a flow-through reactor system with controlled gas delivery, plasma generation components, and nanoparticle collection mechanisms. The following protocol outlines the key steps for implementing this method:

Reactant Preparation and System Setup:

- Utilize high-purity silane (SiH₄) as the primary silicon precursor, often diluted in carrier gases such as argon or helium to control reaction kinetics.

- Ensure all gas delivery systems employ precision mass flow controllers to maintain consistent stoichiometry and reaction conditions.

- Implement leak-tight stainless steel or glass reactor components compatible with vacuum operations and resistant to silicon deposition.

Plasma Generation and Reaction Parameters:

- Apply radio frequency (13.56 MHz) or microwave (2.45 GHz) power to electrodes surrounding the reaction chamber to generate plasma.

- Maintain operating pressures between 0.1-10 Torr to optimize mean free path and reaction efficiency.

- Control plasma power density between 0.1-5 W/cm³ to balance between complete precursor decomposition and excessive particle aggregation.

- Regulate substrate temperature, typically between 100-500°C, to influence nanocrystal crystallinity and surface characteristics.

Nanoparticle Collection and Processing:

- Collect synthesized nanoparticles on mesh filters, cooled substrates, or in liquid traps downstream from the plasma zone.

- Implement surface passivation procedures immediately after collection to prevent oxidation, often through controlled oxidation to create thin silica shells or organic functionalization.

- For photonic applications, perform additional hydrosilylation reactions with terminal alkenes to impart colloidal stability and tune optical properties [6].

Yield Optimization Strategies

Maximizing yield in non-thermal plasma synthesis requires careful optimization of multiple interdependent parameters. Experimental evidence suggests several key strategies for enhancing production efficiency:

Precursor Concentration and Flow Dynamics:

- Higher silane concentrations generally increase nucleation rates and production yields but may lead to broader size distributions due to increased particle aggregation.

- Optimal flow rates balance residence time in the plasma zone with continuous replenishment of precursor species, typically between 10-100 sccm for laboratory-scale systems.

- Introduction of hydrogen gas (5-20% by volume) can enhance crystalline quality by etching amorphous silicon and passivating surface dangling bonds [39].

Plasma Energy Coupling:

- Moderate power densities (1-3 W/cm³) typically optimize the balance between complete precursor decomposition and controlled growth conditions.

- Pulsed plasma operation can improve energy efficiency by separating nucleation and growth phases, reducing particle agglomeration.

- Electrode configuration and geometry significantly influence plasma stability and volume, with larger plasma volumes enabling higher production throughput.

Reactor Design Considerations:

- Low-pressure environments reduce gas-phase collisions and particle aggregation, favoring narrow size distributions.