Nanocrystal Formation: Decoding Nucleation, Growth Mechanisms, and Advanced Drug Delivery Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the nucleation and growth mechanisms governing nanocrystal formation, a critical technology for enhancing the bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs.

Nanocrystal Formation: Decoding Nucleation, Growth Mechanisms, and Advanced Drug Delivery Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the nucleation and growth mechanisms governing nanocrystal formation, a critical technology for enhancing the bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it delves into foundational theories, from classical and non-classical nucleation to thermodynamic and kinetic growth models. The scope extends to practical methodologies like top-down and bottom-up synthesis, advanced applications in targeted drug delivery and dermal products, and essential troubleshooting for stability and polymorph control. Finally, it covers the critical validation and regulatory pathways, including in vitro-in vivo correlations and the analysis of approved nanocrystal drug products, offering a complete roadmap from fundamental science to clinical application.

The Science of Initiation: Unraveling Nucleation and Growth Mechanisms in Nanocrystal Formation

The formation of nanocrystals is a fundamental process underpinning advancements in fields ranging from drug development to materials science. For decades, Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) has provided the primary conceptual framework for understanding this process, depicting a direct, single-step pathway where dissolved monomers assemble into critical nuclei that then grow into crystals [1]. However, advanced experimental techniques have revealed a more complex reality, uncovering non-classical pathways that proceed through intermediate phases and particle-based attachment [2] [3]. This in-depth technical guide examines the core principles, experimental evidence, and mechanistic distinctions between classical and non-classical nucleation, with a specific focus on the role of amorphous precursors and two-step pathways in the context of nanocrystal formation research.

Theoretical Foundations of Nucleation

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT)

Established in the 1930s, Classical Nucleation Theory describes crystal formation as a single-step process driven by stochastic fluctuations in a supersaturated solution. The theory posits that the free energy change ( \Delta G ) for forming a spherical nucleus of radius ( r ) is given by:

( \Delta G = -\frac{4\pi kB T \ln S}{3vm}r^3 + 4\pi\gamma r^2 )

where ( kB ) is Boltzmann's constant, ( T ) is temperature, ( S ) is the supersaturation ratio, ( vm ) is the molecular volume, and ( \gamma ) is the interfacial tension [1]. This equation reveals a fundamental competition between the bulk free energy driving the phase transformation (favorable, scaling with ( r^3 )) and the surface energy cost of creating a new interface (unfavorable, scaling with ( r^2 )).

A critical concept in CNT is the critical radius ( r_{crit} ), which represents the size at which a nucleus becomes stable and can grow spontaneously. This is derived by setting ( \partial\Delta G/\partial r = 0 ), yielding:

( r{crit} = -\frac{2\gamma vm}{k_B T \ln S} )

The corresponding activation barrier ( \Delta G_{crit} ) is:

( \Delta G{crit} = \frac{16\pi\gamma^3 vm^2}{3(k_B T \ln S)^2} )

CNT makes several key assumptions, including the "capillary assumption" that nascent nuclei possess the same interfacial tension and structure as the macroscopic bulk material. While this simplification makes the theory mathematically tractable, it often fails to quantitatively predict experimental nucleation phenomena, particularly for crystals forming from solution [1].

Non-Classical Nucleation Theories

Non-classical nucleation encompasses several pathways that deviate from the classical monomer-by-monomer addition model. The most prominent is the two-step nucleation mechanism, which involves the formation of a metastable intermediate prior to crystallization [1]. This pathway often proceeds through the initial formation of dense liquid phases or amorphous precursors that subsequently reorganize into crystalline materials [3].

In the prenucleation cluster (PNC) pathway, ions or molecules first form thermodynamically stable, highly dynamic clusters that exist as solutes without a defined phase interface. Upon reaching a critical ion activity product, these clusters undergo a structural change, becoming phase-separated nanodroplets. These nanodroplets then aggregate and coalesce into larger liquid intermediates, which eventually dehydrate and solidify into amorphous phases before transforming into crystals [1].

Another significant non-classical mechanism is crystallization by particle attachment (CPA), where crystals grow not by individual atom or ion addition, but through the assembly of larger nanoparticles. A specific biological manifestation of this is crystallization by amorphous particle attachment (CAPA), prevalent in biogenic minerals where it allows organisms to intervene at multiple stages of crystal growth [3].

Table 1: Core Principles of Classical vs. Non-Classical Nucleation Theories

| Feature | Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) | Non-Classical Nucleation |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Pathway | Single-step, direct | Multi-step, indirect |

| Intermediate States | None | Amorphous phases, dense liquid droplets, pre-nucleation clusters |

| Growth Mechanism | Monomer-by-monomer addition | Particle attachment, aggregation |

| Critical Size Concept | Well-defined critical radius based on energy balance | Multiple stability thresholds for different stages |

| Interfacial Assumptions | Macroscopic interfacial tension applies to nuclei | Evolving interfaces, non-bulk structure in intermediates |

| Predicted Morphology | Faceted crystals following equilibrium habit | Complex, non-equilibrium morphologies, mesocrystals |

Experimental Methodologies and Visualization

Advanced Imaging Techniques

Direct observation of nucleation and growth processes requires sophisticated imaging technologies capable of resolving structures at the nanoscale and atomic level.

In-situ Liquid Phase Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (STEM) enables real-time observation of nucleation events in liquid environments. The development of graphene liquid cells (GLCs) has been particularly transformative, as graphene's atomic thinness (≤1 nm) and impermeability allow for high-resolution imaging while containing liquid reagents. This technology provides both high spatial resolution (Ångström level) and temporal resolution (up to 2 frames/second), enabling researchers to track nucleation processes atom-by-atom [2].

Conventional Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) remains invaluable for post-process analysis of nanoparticle morphology, size, and distribution within tissues and cells. When combined with energy-filtered TEM (EFTEM), it enables elemental mapping to distinguish nanoparticles from cellular structures. For three-dimensional structural analysis, electron tomography can reconstruct nanoparticle morphology and their interactions with cellular organelles [4].

Femtosecond X-ray scattering provides complementary information about atomic-scale dynamics during phase transformations. This technique can visualize light-induced anisotropic strains in nanocrystals with atomic-scale resolution on femtosecond timescales, capturing large-amplitude structural changes during early transformation stages [5].

Experimental Protocol: In-situ Observation of Platinum Nanocrystal Formation

The following protocol, adapted from the study visualizing platinum nanocrystal nucleation and growth [2], details the methodology for direct observation of nucleation mechanisms:

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a 5 mM aqueous solution of Na₂PtCl₄·2H₂O as the metal precursor.

- Create graphene liquid cells (GLCs) by encapsulating the precursor solution between two graphene sheets, forming liquid nanoreactors approximately 50 nm thick.

Microscopy Setup:

- Utilize an aberration-corrected Scanning Transmission Electron Microscope (STEM) equipped with a high-speed detector.

- Operate in Annular Dark-Field (ADF) mode for Z-contrast imaging.

- Set electron dose rate to approximately 4.2 × 10³ electrons/Ųs to balance imaging resolution with minimized beam effects.

Data Acquisition:

- Initiate electron beam exposure to reduce Pt precursor, generating hydrated electrons (eₕ⁻) and hydrogen radicals (H·) that serve as reducing agents.

- Acquire image sequences at atomic resolution with temporal resolution of 2 frames/second.

- Record continuous data from initial precursor state through nucleation and growth to mature nanoparticles.

Data Analysis:

- Track particle size and count over time to identify growth stages.

- Analyze Fourier transforms (FT) of high-resolution images to assess crystallinity evolution.

- Monitor local intensity changes to detect depletion zones around growing clusters.

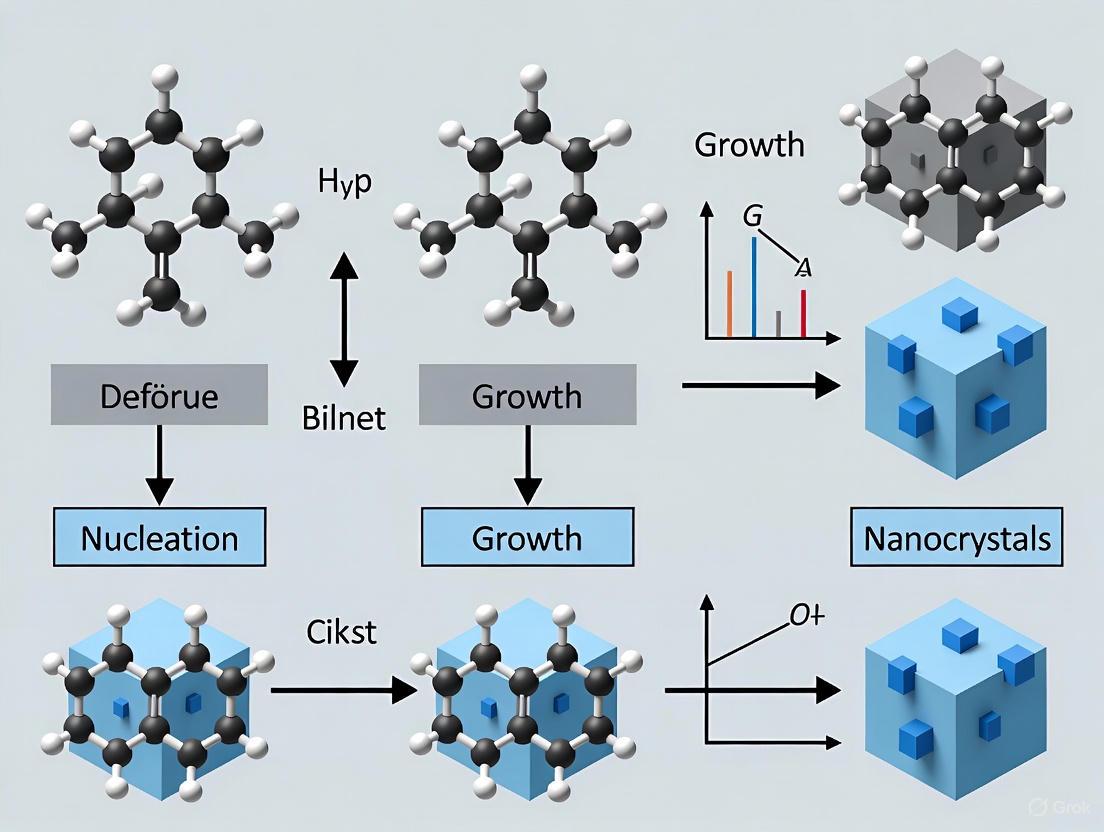

Diagram 1: Multi-Step Nucleation Pathway of Platinum Nanocrystals

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Nucleation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Tetrachloroplatinate (Na₂PtCl₄·2H₂O) | Metal precursor for nanocrystal synthesis | Formation of Pt nanoparticles in graphene liquid cells [2] |

| Graphene Liquid Cells (GLCs) | Nanoscale liquid containment for TEM | High-resolution imaging of nucleation in aqueous environment [2] |

| Silicon Nitrate Membranes | Support structure for conventional TEM | Sample mounting for nanoparticle-cell interaction studies [4] |

| Strontium & Aluminum Nitrates | Precursors for metal oxide synthesis | Solvothermal synthesis of SrAl₁₂O₁₉ precursor particles [6] |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Capping agent and stabilizer | Controlling particle growth and preventing aggregation [6] |

| Cadmium Selenide/Sulfide Nanocrystals | Model semiconductor systems | Studying ultrafast strain dynamics under photoexcitation [5] |

Comparative Analysis of Nucleation Pathways

Distinct Growth Mechanisms and Kinetics

The transition from nucleation to growth reveals fundamentally different mechanisms between classical and non-classical pathways, each with distinct kinetic profiles.

Classical Growth Modes operate through monomer addition and are well-described by the terrace-ledge-kink (TLK) model. At low supersaturation, growth proceeds via a screw-dislocation-driven (spiral growth) mechanism where dislocations provide permanent kink sites. At intermediate supersaturation, two-dimensional surface nucleation (birth and spread growth) becomes dominant, while at high supersaturation, the crystal surface becomes rough and growth occurs through immediate monomer incorporation at all surface sites [3].

Non-Classical Growth Modes include oriented attachment (OA), where crystalline nanoparticles with aligned crystallographic orientations coalesce to form larger single crystals, and amorphous particle attachment, where non-crystalline particles aggregate before crystallizing. These pathways often operate in tandem, as demonstrated in platinum nanocrystal formation where an initial atomic attachment stage (depleting the local monomer concentration) is followed by a second stage dominated by particle attachment and coalescence [2].

The kinetics of these processes can be modeled using extended versions of the Johnson-Mehl-Avrami-Kolmogorov (JMAK) equation, which can incorporate time-dependent growth and nucleation rates. For diffusion-controlled growth where the growth rate ( G(t) ) varies as ( t^{-1/2} ), the transformed fraction ( f(t) ) follows:

( f(t) = 1 - \exp(-kt^n) )

where both the rate constant ( k ) and Avrami exponent ( n ) reflect the specific growth and nucleation mechanisms operative in the system [7].

Quantitative Comparison of Nucleation Parameters

Table 3: Experimental Observations of Nucleation and Growth Parameters

| Parameter | Classical Pathway | Non-Classical Pathway | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Size for Crystallization | Not applicable (direct crystallization) | ~1 nm amorphous clusters | Pt nanocrystals transition at ~1 nm diameter [2] |

| Transformation Timescale | Single activation barrier | Multiple sequential steps | Pt nanocrystals: amorphous for ~30s before crystallizing [2] |

| Maximum Strain During Growth | Typically minimal | Can exceed 1% | CdS/CdSe nanocrystals show ~1.2% radial strain [5] |

| Growth Rate Dependence | Constant or decreasing with time | Can increase during particle attachment stage | Two distinct stages in Pt growth: atomic then particle attachment [2] |

| Activation Barrier | ( \Delta G{crit} = \frac{16\pi\gamma^3 vm^2}{3(k_B T \ln S)^2} ) | Multiple barriers for different stages | Energetics include aggregation, reorganization, crystallization [1] |

Implications for Nanocrystal Engineering and Drug Development

The distinction between classical and non-classical nucleation pathways has profound practical implications for controlling nanocrystal properties in technological applications.

In pharmaceutical development, understanding and controlling crystallization pathways is essential for obtaining desired polymorphs with optimal bioavailability. Small molecular modifications can significantly alter the crystallization landscape, as demonstrated by ABT-072 and ABT-333—structural analogs that differ only by a minor substituent change but exhibit dramatically different polymorphism and solubility behavior. While ABT-072 displays diverse anhydrous polymorphism, ABT-333 forms only a single anhydrous polymorph under similar conditions, a distinction captured by crystal structure prediction (CSP) calculations [8].

For functional nanomaterials, non-classical pathways offer unique opportunities for morphological control. The crystallization of SrAl₁₂O₁₉ nanocrystals from amorphous precursors under high-temperature annealing proceeds through a complex sequence involving densification, crystallite domain formation, oriented attachment, surface nucleation, two-dimensional growth, and surface diffusion—ultimately yielding thermodynamically favored hexagonal platelet crystals [6]. Similar pathways in biogenic minerals enable the formation of complex morphologies like the spherical lenses in brittle stars and hierarchical porous microstructures in sea urchins, which defy conventional crystallographic expectations [3].

The recognition that multiple nucleation pathways may operate simultaneously or competitively under similar conditions necessitates sophisticated characterization approaches. As demonstrated by in-situ studies of CaCO₃ nucleation, classical and non-classical mechanisms can occur in parallel, with their relative dominance determined by precise solution conditions and interfacial environments [1] [2].

The paradigm of crystal formation has expanded significantly beyond the classical nucleation theory to encompass a rich landscape of non-classical pathways involving amorphous intermediates, pre-nucleation clusters, and particle-based assembly. These multi-step mechanisms, once considered exceptions, are now recognized as fundamental processes in both biological and synthetic systems. The distinction between these pathways has material consequences, enabling precise morphological and crystallographic control in biominerals and offering new strategies for engineering functional nanomaterials with tailored properties. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these mechanistic differences provides not only deeper fundamental insight but also practical tools for controlling crystallization outcomes—from pharmaceutical polymorph selection to the synthesis of advanced nanocrystalline materials. As characterization techniques continue to improve, particularly in-situ methods with high spatial and temporal resolution, our understanding of these complex pathways will further refine, enabling increasingly sophisticated control over one of materials science's most fundamental processes.

The formation and stability of nanocrystals are governed by fundamental thermodynamic principles that dictate nucleation, growth, and dissolution behaviors. Among these principles, the Kelvin equation represents a cornerstone relationship that describes how particle size influences solubility—a phenomenon with profound implications for nanocrystal formulation, stability, and performance in pharmaceutical applications. As the pharmaceutical industry increasingly turns to nanocrystal technology to enhance the bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs, understanding these thermodynamic drivers becomes paramount for researchers and drug development professionals.

This technical guide explores the theoretical foundations of the Kelvin equation and its critical relationship with saturation solubility within the context of nanocrystal formation mechanisms. With an estimated 70-90% of new chemical entities (NCEs) exhibiting poor solubility, which directly limits absorption and therapeutic efficacy, the manipulation of solubility through nanocrystal formation has emerged as a vital formulation strategy [9]. The precise control over nanocrystal size, shape, and surface chemistry enabled by modern synthesis techniques allows researchers to harness thermodynamic principles for optimizing drug delivery systems [10].

Theoretical Foundations

The Kelvin Equation: Core Principles

The Kelvin equation establishes the fundamental relationship between particle curvature and solubility, predicting that smaller particles exhibit higher solubility than their bulk counterparts due to increased surface energy. This relationship can be expressed mathematically as:

[ \ln\left(\frac{S}{S0}\right) = \frac{2\gamma Vm}{rRT} ]

Where:

- (S) is the solubility of the nanocrystal

- (S_0) is the solubility of the bulk material

- (\gamma) is the surface free energy

- (V_m) is the molar volume

- (r) is the radius of the particle

- (R) is the ideal gas constant

- (T) is the absolute temperature

This size-dependent solubility phenomenon has direct implications for nanocrystal stability and Ostwald ripening—a process where larger particles grow at the expense of smaller ones due to solubility differences [11]. The theoretical framework provided by the Kelvin equation enables researchers to predict and control these processes during nanocrystal formation and storage.

Saturation Solubility in Nanocrystal Systems

Saturation solubility represents the maximum concentration of a compound that can dissolve in a solution at equilibrium with its solid phase. For nanocrystals, this fundamental property is intrinsically linked to particle size through the Kelvin equation, creating a dynamic interplay that influences both nucleation kinetics and crystal growth mechanisms [11].

The dissolution process for nanocrystals involves three primary thermodynamic steps: dissociation from the crystal lattice, cavity formation in the solvent, and solvation of the free molecule. The strong intermolecular bonds and complex interaction patterns in crystal lattices often limit dissociation, particularly for high-melting-point compounds sometimes referred to as 'brick dust' molecules. Simultaneously, hydrophobic compounds with high octanol-water partition coefficients (logP > 2-3) face solvation limitations, described as 'greaseball' molecules [11]. Nanocrystal technology primarily addresses the former limitation by increasing surface area and applying the Kelvin effect to enhance dissolution.

Table 1: Key Molecular Properties Influencing Nanocrystal Solubility

| Property | Impact on Solubility | Experimental Determination | Formulation Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melting Point (Tm) | Compounds with Tm > 200°C show solid-state-limited solubility [11] | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Amorphization, salt formation beneficial |

| logP/logD | Values > 2-3 indicate solvation-limited solubility [11] | Shake-flask method, HPLC | Lipid-based formulations preferred |

| Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) | Strong correlation with solubility prediction [12] | Molecular dynamics simulations | Surface modification strategies |

| Coulombic & LJ Interaction Energies | Key descriptors for solute-solvent interactions [12] | Molecular dynamics simulations | Solvent selection optimization |

Experimental Methodologies and Validation

Advanced Crystallization Monitoring

Recent research from UC Berkeley has revealed sophisticated crystallization pathways for nanocrystals that provide experimental validation of thermodynamic principles. Using lead sulfide nanocrystals suspended in solution, researchers employed powerful X-ray scattering techniques to observe in real-time how particles organize into ordered, repeating lattices [13].

The experimental protocol involved:

- System Preparation: Lead sulfide nanocrystals were suspended in solution with carefully controlled ionic strength

- Environmental Tuning: Soluble ions were used to tune nanocrystal interactions rather than simply packing particles more tightly

- Real-Time Monitoring: X-ray scattering techniques tracked assembly processes with high temporal resolution

- Pathway Analysis: Crystallization mechanisms were classified as direct versus liquid-intermediate pathways

This methodology demonstrated that crystallization does not always occur in a single step. Instead, particles often first condense into a dense, liquid-like state before reorganizing into an ordered crystal. This temporary metastable liquid phase significantly accelerates crystallization and produces crystals with fewer defects. By carefully adjusting salt concentration, the research team controlled assembly speed over three orders of magnitude—from seconds to hours [13].

Molecular Dynamics for Solubility Prediction

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as powerful computational tools for modeling the physicochemical properties governing nanocrystal solubility, providing molecular-level insights that complement experimental approaches. A recent comprehensive study compiled a dataset of 211 drugs from diverse classes and subjected them to MD simulation to extract properties relevant to solubility prediction [12].

The detailed experimental protocol included:

- System Setup: Simulations conducted in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble using GROMACS 5.1.1 software with the GROMOS 54a7 force field

- Property Calculation: Ten MD-derived properties were extracted along with experimental logP values

- Feature Selection: Statistical analysis identified the most influential properties for solubility prediction

- Machine Learning Integration: Four ensemble algorithms (Random Forest, Extra Trees, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting) were employed to develop predictive models

The research identified seven key properties with significant influence on solubility prediction: logP, Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), Coulombic interaction energy (Coulombic_t), Lennard-Jones interaction energy (LJ), Estimated Solvation Free Energy (DGSolv), Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), and Average number of solvents in Solvation Shell (AvgShell) [12]. The Gradient Boosting algorithm achieved the best predictive performance with R² = 0.87 and RMSE = 0.537, demonstrating the power of integrating MD simulations with machine learning for solubility forecasting.

Diagram Title: Nanocrystal Formation Pathways

Computational Approaches and Predictive Modeling

In Silico Modeling for Solubility Enhancement

Predictive modeling via computational simulation represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical formulation, replacing empirical trial-and-error approaches with rational, efficient strategies. These advanced methodologies employ mathematical algorithms, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning to model complex biological, chemical, and physical processes, providing data-driven insights into drug behavior and formulation strategies [9].

The application of predictive modeling for solubility and bioavailability enhancement offers several distinct advantages:

- Efficient Formulation Optimization: Researchers can explore and optimize various formulation parameters, such as excipient selection and processing conditions, through simulation rather than extensive laboratory experimentation

- Early Issue Identification: Potential issues related to solubility and bioavailability can be identified early in the development process, allowing for proactive resolution

- Resource Conservation: By focusing experimental efforts on formulations with higher probability of success, organizations can significantly reduce resource consumption associated with materials, equipment, and time

- Mechanistic Insights: Advanced models provide unprecedented insights into the underlying molecular interactions and mechanisms governing solubility, enabling more informed decision-making [9]

Commercial platforms like Thermo Fisher Scientific's Quadrant 2 predictive platform exemplify this approach, using computational methods to analyze a drug compound's unique molecular structure and chemical characteristics to identify optimal bioavailability and solubility enhancement techniques [9].

Table 2: Key MD-Derived Properties for Solubility Prediction

| Property | Computational Method | Correlation with Solubility | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| SASA | Molecular Dynamics | R² = 0.82 [12] | Reflects molecular surface accessible to solvent |

| logP | Experimental/QSPR | R² = 0.79 [12] | Measures hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity balance |

| DGSolv | Free Energy Calculations | R² = 0.76 [12] | Quantifies energy of solvation process |

| Coulombic_t | Nonbonded Interaction Analysis | R² = 0.71 [12] | Electrostatic solute-solvent interactions |

| LJ | Nonbonded Interaction Analysis | R² = 0.68 [12] | Van der Waals solute-solvent interactions |

Machine Learning Integration

The integration of machine learning with molecular dynamics has created powerful predictive tools for solubility assessment. By leveraging ensemble algorithms like Random Forest, Extra Trees, XGBoost, and Gradient Boosting, researchers can now accurately forecast solubility based on MD-derived properties, achieving performance comparable to traditional structure-based prediction models [12].

This approach is particularly valuable for addressing the complex challenges of biorelevant solubility prediction in media mimicking human intestinal fluids. These complex solvents contain additives such as bile salts, phospholipids, cholesterol, and lipids to reflect fasted and fed intestinal states, creating a challenging prediction environment that extends beyond simple aqueous solubility [11]. Machine learning models trained on comprehensive datasets can navigate this complexity, providing critical insights for formulation development.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Nanocrystal Solubility Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Lead Sulfide Nanocrystals | Model system for crystallization studies [13] | Fundamental mechanism research |

| GROMACS Software | Molecular dynamics simulation package [12] | Computational property prediction |

| GROMOS 54a7 Force Field | Molecular modeling parameters [12] | MD simulation of solute-solvent systems |

| Simulated Intestinal Fluids | Biorelevant solubility assessment [11] | Prediction of in vivo performance |

| X-ray Scattering Equipment | Real-time crystallization monitoring [13] | Experimental pathway validation |

The Kelvin equation and saturation solubility principles provide the fundamental thermodynamic framework underlying nanocrystal behavior and stability. As pharmaceutical research continues to confront the challenges posed by poorly soluble drug candidates, harnessing these relationships through advanced experimental and computational approaches becomes increasingly critical. The integration of molecular dynamics simulations, machine learning, and sophisticated crystallization monitoring techniques enables researchers to not only predict solubility behavior but also to design optimized nanocrystal formulations with enhanced bioavailability. Continuing advancement in these areas promises to accelerate drug development timelines while improving the efficacy of therapeutics for patients.

The synthesis of nanocrystals with precisely controlled dimensions remains a cornerstone of advanced materials science, with implications spanning optoelectronics, catalysis, and biomedical applications. Central to this endeavor is understanding the kinetic processes that govern nanocrystal formation, from the initial activation of molecular precursors to the final focusing of the size distribution. This guide examines the theoretical frameworks and experimental methodologies that enable researchers to navigate these complex kinetic pathways. Framed within broader research on nucleation and growth mechanisms, these models provide a predictive foundation for moving beyond empirical synthesis toward rational design of nanocrystals with tailored properties. The 2023 Nobel Prize in Chemistry recognized the profound importance of controlled nanocrystal synthesis, further highlighting the critical need for sophisticated kinetic models that bridge atomic-scale events and macroscopic observables [10].

Kinetic Framework of Nanocrystal Formation

The Five-Stage Kinetic Model

A comprehensive kinetic model for semiconductor nanocrystal synthesis reveals five distinct temporal regions that characterize the evolution from precursor compounds to final nanocrystals [14]. This model integrates an activation mechanism for precursor conversion to monomers, discrete rate equations for small cluster formation, and a continuous Fokker-Planck equation for larger cluster growth.

Table 1: Stages of Nanocrystal Formation in Kinetic Models

| Stage | Key Processes | Governing Factors | Experimental Observables |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Monomer Generation | Precursor conversion to reactive monomers | Activation energy, temperature | Precursor consumption rate |

| 2. Small Cluster Formation | Nucleation and early growth | Critical nucleus size, supersaturation | Initial particle count |

| 3. Size Distribution Focusing | Competitive growth | Precursor depletion | Decreasing polydispersity |

| 4. Pseudo-Steady State | Balanced attachment/detachment | Surface energy effects | Stable mean size |

| 5. Distribution Broadening | Ostwald ripening | Solubility differences | Increasing polydispersity |

The model identifies two key non-dimensional parameter combinations that serve as guiding principles for experimental design optimization. Contrary to conventional understanding that diffusion controls size distribution focusing, this model demonstrates that focusing can occur under purely reaction-controlled conditions [14]. This distinction has profound implications for synthesis design, particularly through temperature modulation or additive introduction to enhance precursor conversion rates while minimizing polydispersity.

Quantitative Parameters and Their Impact

The kinetic trajectory through these stages is governed by specific quantitative relationships that determine the final nanocrystal characteristics. Optimization requires careful balancing of these parameters to achieve desired size distributions.

Table 2: Key Kinetic Parameters and Their Impact on Nanocrystal Synthesis

| Parameter | Mathematical Expression | Impact on Size Distribution | Experimental Control Levers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monomer Generation Rate | ( R = A e^{-E_a/RT} ) | Determines nucleation burst duration | Temperature, precursor concentration, catalysts |

| Critical Nucleus Size | ( n^* = \frac{2\sigma^3}{27(kT\ln S)^3} ) | Defines stable nucleus formation | Supersaturation (S), surface energy (σ) |

| Size Distribution Focus Parameter | ( \Gamma = \frac{kg C0}{kn n0} ) | Controls distribution narrowing | Growth vs nucleation rate balance |

| Activation-Conversion Balance | ( \Lambda = \frac{ka [A]}{kd} ) | Affects intermediate stability | Additive concentration, precursor reactivity |

For a given set of reaction parameters, an optimum exists in both the duration of high-temperature treatment and additive concentration that minimizes polydispersity [14]. This optimum represents the most efficient path through the kinetic landscape, balancing nucleation and growth rates to achieve monodisperse populations.

Computational Modeling Approaches

Kinetic Monte Carlo Methods

Kinetic Monte Carlo (KMC) simulations provide a powerful atomistic approach for modeling nanocrystal formation kinetics. KMC operates on the fundamental principle of simulating state-to-state transitions as a Markov chain, where the probability of transitioning between states depends only on the current state, not on previous history [15]. The method captures rare event dynamics that characterize many processes in nanocrystal formation, where high activation barriers create timescale disparities between atomic vibrations (picoseconds) and infrequent barrier-crossing events (potentially seconds or longer).

The time evolution of the probability ( P_i(t) ) of the system being in state ( i ) at time ( t ) is governed by the Markovian master equation:

[ \frac{dPi(t)}{dt} = -\sum{j \neq i} k{ij}Pi(t) + \sum{j \neq i} k{ji}P_j(t) ]

where ( k_{ij} ) represents the rate constant for transitioning from state ( i ) to state ( j ) [15]. For nanocrystal formation, these states represent different atomic configurations, and the rate constants describe elementary processes such as monomer attachment, detachment, diffusion, and chemical reactions.

KMC Implementation Framework

Implementing KMC for nanocrystal growth requires careful mapping of physical processes to computational algorithms. The approach is particularly valuable for simulating surface diffusion, crystal growth, and heterogeneous catalysis, covering both transient and steady-state kinetics [15].

Table 3: KMC Model Components for Nanocrystal Growth Simulations

| Model Component | Description | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Lattice Definition | Mapping of crystal structure to discrete sites | Lattice type, coordination, neighborhood relations |

| Elementary Processes | Atomic-scale events with associated rate constants | Attachment, detachment, diffusion, transformation |

| Rate Constants | Temperature-dependent probabilities for each process | ( k = \nu e^{-Ea/kBT} ) with preexponential factor ( \nu ) |

| Timescale Management | Algorithms for handling disparate rates | Fast-process rejection, time acceleration techniques |

| Lateral Interactions | Energetic coupling between adjacent species | Cluster expansions, nearest-neighbor parameters |

In practice, KMC simulations for nanocrystal growth must address several challenges, including timescale disparities between fast diffusion processes and slow chemical reactions. Recent acceleration algorithms help overcome these limitations, enabling more comprehensive simulations of realistic systems [15]. Commercial implementations, such as the Sentaurus Process KMC module, demonstrate the application of these methods to practical materials systems, modeling individual impurity atoms and point defects in three dimensions without requiring a continuum mesh [16].

Figure 1: Kinetic Pathway from Precursor to Mature Nanocrystal

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

In-Situ Liquid Cell STEM for Atomic-Scale Observation

Direct experimental observation of nanocrystal formation mechanisms at atomic resolution provides critical validation for kinetic models. Recent advances in in-situ liquid cell scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) enable real-time tracking of nucleation and growth events. The methodology employing graphene liquid cells (GLCs) offers particularly high spatial and temporal resolution, with cell thickness below 1 nm allowing imaging at the Ångström level [2].

Protocol: In-Situ Observation of Platinum Nanocrystal Growth

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare 5 mM aqueous solution of Na₂PtCl₄·2H₂O as platinum precursor

- Encapsulate solution in graphene liquid cell, creating nanoscale reactors

- Optimize liquid thickness to <50 nm for high-resolution imaging

Imaging Parameters:

- Use aberration-corrected STEM with annular dark-field (ADF) detection

- Set electron dose rate to approximately 4.2 × 10³ electrons/Ųs

- Acquire images at 2 frames/s temporal resolution

- Calibrate magnification to achieve ≤0.3 nm/pixel resolution

Data Collection:

- Record continuous image sequences during electron beam exposure

- Track multiple nanoparticle formations simultaneously

- Monitor depleted zones around growing clusters

- Capture coalescence events during later growth stages

Analysis Methods:

- Measure particle size and count as function of time

- Compute Fourier transforms of individual nanoparticles to assess crystallinity

- Track amorphous-to-crystalline transition points

- Analyze attachment mechanisms (atomic vs. particle)

This approach has revealed a two-stage growth mechanism for platinum nanocrystals: an initial atomic attachment stage until local precursor depletion, followed by particle attachment through various atomic pathways [2]. The critical size for amorphous-to-crystalline transition was observed at approximately 1 nm diameter, providing quantitative boundaries for kinetic models.

Population Balance Modeling and Data Mining

For systems where direct atomic-scale observation is challenging, population balance models combined with statistical analysis of literature data offer an alternative approach to kinetic parameter estimation. A comprehensive data mining study analyzed 336 datapoints of kinetic parameters from 185 different sources, employing hierarchical cluster analysis and random forest classification to identify patterns in crystallization kinetics [17].

Protocol: Population Balance Model Development

Kinetic Parameter Extraction:

- Collect literature data on solute, solvent, kinetic expressions, and parameters

- Categorize by crystallization method and seeding conditions

- Normalize kinetic parameters for cross-study comparison

Cluster Analysis:

- Perform hierarchical cluster analysis on kinetic parameters

- Identify naturally occurring groupings within the data

- Validate cluster stability through statistical measures

Predictive Model Construction:

- Develop random forest classification models using solute descriptors, solvent properties, and crystallization methods as classifiers

- Train models on clustered data sets

- Validate model accuracy through cross-validation

Model Application:

- Use classified parameters as initial estimates for new systems

- Refine parameters through limited experimental validation

- Implement in population balance equations for process prediction

This data-driven approach achieved classification accuracy exceeding 70%, providing reasonable initial estimates for kinetic parameters without extensive experimentation [17]. The methodology is particularly valuable for pharmaceutical development professionals seeking to accelerate process optimization.

Figure 2: Experimental-Computational Workflow for Kinetic Analysis

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful investigation of nanocrystal formation kinetics requires carefully selected materials and reagents that enable precise control over reaction pathways. The following toolkit summarizes critical components used in advanced kinetic studies.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Nanocrystal Kinetic Studies

| Category | Specific Examples | Function in Kinetic Studies | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor Compounds | Na₂PtCl₄·2H₂O, Lead halide perovskites, Metal acetylacetonates | Source of monomer species | Controlled reactivity, solubility, reduction potential |

| Stabilizing Ligands | Oleic acid, Oleylamine, Trioctylphosphine oxide | Surface binding to control growth kinetics | Selective facet binding, steric bulk, coordination strength |

| Solvents | Octadecene, Toluene, Water, Diphenyl ether | Reaction medium for nanocrystal formation | Boiling point, polarity, coordinating ability, viscosity |

| Reducing Agents | Diisobutylaluminum hydride, Superhydride, Sodium borohydride | Electron donors for precursor activation | Controlled reduction potential, compatibility with solvent system |

| Additives | Metal halides, Alkali acetates, Fatty acids | Modifiers of reaction kinetics | Selective complexation, surface energy modification, precursor stabilization |

| Reference Materials | CNCD-1 cellulose nanocrystals, Gold nanorods | Method validation and instrument calibration | Certified size distribution, morphology, stability |

The selection of appropriate precursor compounds is particularly critical, as their reactivity determines the monomer generation rate that initiates the kinetic cascade [14] [2]. Similarly, the choice of stabilizing ligands directly influences surface kinetics during growth, enabling size and shape control through selective facet stabilization. Recent advances demonstrate that increasing precursor reactivity enables continuous tunability of copper nanocrystals from single-crystalline to twinned and stacking fault-lined structures, highlighting the profound impact of kinetic control on material properties [10].

Kinetic control models provide an essential framework for understanding and manipulating nanocrystal formation from initial monomer activation to final size distribution focusing. The integration of theoretical models, computational simulations, and advanced characterization techniques creates a feedback loop that continuously refines our understanding of these complex processes. As experimental methods achieve higher temporal and spatial resolution, and computational models incorporate more realistic interactions, the predictive power of these kinetic models continues to improve. This progression enables increasingly precise synthesis of nanocrystals with tailored properties for specific applications in photonics, electronics, catalysis, and medicine, fulfilling the promise of nanocrystals as building blocks for next-generation technologies.

Nonstoichiometric Nucleation in Multicomponent Systems

Nonstoichiometric nucleation describes the process where the initial crystalline embryo possesses a chemical composition that differs from both the parent phase and the final stable crystalline phase. This phenomenon represents a significant departure from classical nucleation theory and has profound implications for controlling the structure and properties of multicomponent crystals. In multicomponent systems, nonstoichiometric nucleation frequently occurs through pathways involving amorphous intermediates or metastable crystalline phases that act as precursors to the final stable phase [18]. This nucleation mechanism is particularly relevant in functional materials such as intermetallic compounds, where non-equilibrium phenomena like disorder trapping and inverted partitioning occur during rapid solidification [19]. The ability to understand and control nonstoichiometric nucleation pathways enables scientists to design materials with specific architectural features and physical properties that are not accessible through equilibrium synthesis routes.

The thermodynamic driving force for nonstoichiometric nucleation originates from imbalances in the concentrations of reduced elements during the initial synthesis stages [18]. When nonstoichiometric nuclei begin to grow, secondary elements can either deposit physically on the growing nuclei or form atomic mixtures through diffusion and rearrangement processes. The competition between these pathways—mixture formation versus physical deposition—ultimately determines the final nanocrystal shape and chemical composition. When the free energy change for mixture formation is highly negative (ΔGAB < -ξ), the final product typically exhibits stoichiometric composition, with its shape determined by the size of the primary nanocrystals [18]. In contrast, when mixture formation and physical deposition compete (-ξ ≤ ΔGAB < 0), both chemical composition and structure become influenced by primary nanocrystal size and the degree of mixture formation at constituent interfaces.

Quantitative Analysis of Nonstoichiometric Growth Kinetics

Experimental investigations across multiple material systems have revealed distinctive kinetic behaviors associated with nonstoichiometric nucleation and growth. The relationship between undercooling (ΔT) and growth velocity (V) provides critical insights into the controlling mechanisms during crystal formation.

Table 1: Dendrite Growth Velocity in Undercooled Co-Si Alloys

| Alloy Composition | Undercooling Range (K) | Maximum Velocity (m/s) | Growth Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-50 at.% Si | 0-255 | ~0.45 | Monotonic velocity increase with undercooling |

| Co-53 at.% Si | 0-180 | ~0.08 | Dual-stage growth: sluggish then abrupt |

| Co-55 at.% Si | 0-165 | ~0.11 | Dual-stage growth: sluggish then abrupt |

Data from [19] demonstrates that alloys with compositions away from the congruently melting point (Co-53 at.% Si and Co-55 at.% Si) exhibit unique dual-stage growth behavior not observed in the stoichiometric Co-50 at.% Si alloy [19]. This dual-stage behavior consists of an initial sluggish growth stage followed by an abrupt acceleration in growth velocity at a critical undercooling threshold. The maximum growth velocity achieved in the non-stoichiometric alloys is substantially lower than in the stoichiometric composition, indicating that compositional deviations from stoichiometry introduce additional kinetic barriers to crystal growth. These experimental observations align with models that incorporate significant solute drag effects during rapid solidification of non-stoichiometric intermetallic compounds [19].

Table 2: Comparison of Theoretical Models for Rapid Solidification

| Model Characteristic | Without Solute Drag | With Solute Drag |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Chemical rate theory | Thermodynamic extremal principle (TEP) |

| Dissipation Processes | Pre-defined | Derived self-consistently |

| Prediction for Co-Si System | Inconsistent with dual-stage growth | Matches experimental dual-stage behavior |

| Solute Trapping | Complete disorder trapping possible | Partial trapping with significant drag |

The application of the Thermodynamic Extremal Principle (TEP) to model rapid solidification of non-stoichiometric intermetallic compounds has demonstrated that only models incorporating solute drag can be derived self-consistently in thermodynamics [19]. This theoretical framework properly accounts for the dissipation processes and their corresponding driving free energies without requiring pre-definition, as needed in chemical rate theory. Comparative studies between model predictions and experimental results in undercooled Co-Si alloys provide compelling evidence for significant solute drag effects during rapid solidification of non-stoichiometric compounds [19].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Melt Fluxing Technique for Undercooling Measurements

The experimental investigation of nonstoichiometric nucleation often requires precise control of solidification conditions. The melt fluxing technique has proven effective for achieving substantial undercooling in intermetallic systems:

Sample Preparation: High-purity ingots (approximately 20g) with nominal compositions are prepared from pure elements (99.999 wt% purity). For Co-Si systems, compositions of Co-50 at.% Si, Co-53 at.% Si, and Co-55 at.% Si have been investigated [19].

Homogenization: Ingots are re-melted at least four times in a vacuum arc melting furnace under Ti-gettered high purity argon atmosphere to ensure chemical homogeneity. Mass loss should be monitored and maintained below 0.3 wt% [19].

Undercooling Procedure: The fluxing technique is applied to undercool the melt. The exact nature of the flux material depends on the specific alloy system but typically involves glassy slags that prevent heterogeneous nucleation.

Velocity Measurement: Temperature profiles and high-speed video camera images are analyzed to determine the relationship between growth velocity (V) and undercooling (ΔT). Error bars for growth velocities are typically set at ±20% based on established methodologies [19].

Molecular Dynamics with Free-Energy Seeding Method

Computational approaches provide atomic-scale insights into nonstoichiometric nucleation mechanisms:

Model Generation: Glass structural models containing 12,000-14,000 atoms are generated using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations through melt-and-quench approaches [20]. For lithium disilicate systems, compositions include 33.3Li₂O·66.7SiO₂ (LS2) and 33Li₂O·66SiO₂·1P₂O₅ (LS2P1) [20].

Simulation Parameters: The leap-frog algorithm encoded in packages such as DL_POLY is used to integrate equations of motion with time steps of 1-2 fs. Systems are typically heated to 3500 K and held for 100 ps to erase memory of initial configurations, then cooled to 300 K with controlled cooling rates [20].

Free-Energy Calculation: The Free-Energy Seeding Method (FESM) evaluates free energy change as a function of crystal radius by embedding subnano-scale spherical crystals in glass models [20]. This approach identifies critical sizes for crystal precipitation and enables comparison with classical nucleation theory.

Cluster Analysis: Modified exploring methods identify structurally similar crystalline clusters in glass models, allowing detection of different embryos (e.g., Li₂Si₂O₅, Li₂SiO₃, Li₃PO₄) [20].

Figure 1: Nonstoichiometric Nucleation Pathway. This diagram illustrates the multi-stage process of nonstoichiometric nucleation, beginning with compositional imbalance in the amorphous phase, proceeding through nonstoichiometric nuclei formation, metastable phase development, and culminating in final crystal structure.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Nonstoichiometric Nucleation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Metals (99.999%) | Source materials for alloy preparation | Co and Si for intermetallic compounds [19] |

| Fluxing Agents | Create glassy slag to prevent heterogeneous nucleation | B₂O₃-based fluxes for undercooling experiments [19] |

| Nucleating Agents | Promote specific crystallization pathways | P₂O₅ in lithium disilicate systems [20] |

| Argon Atmosphere | Prevent oxidation during processing | Ti-gettered high purity argon for melting [19] |

| Molecular Dynamics Force Fields | Describe atomic interactions in simulations | Modified PMMCS force-field for oxide glasses [20] |

The selection of appropriate research reagents is critical for investigating nonstoichiometric nucleation phenomena. High-purity starting materials minimize unintended contamination that could alter nucleation pathways. Fluxing agents enable deep undercooling by preventing heterogeneous nucleation on container surfaces or impurities. deliberately introduced nucleating agents such as P₂O₅ in lithium silicate systems promote specific crystallization pathways and enable the study of how additives influence nonstoichiometric phase selection [20]. Computational studies require carefully parameterized force fields that accurately describe atomic interactions in complex multicomponent systems.

Figure 2: Experimental-Computational Workflow. This diagram outlines the integrated approach combining sample preparation, homogenization, undercooling experiments, characterization, and computational modeling that enables comprehensive investigation of nonstoichiometric nucleation phenomena.

Nonstoichiometric nucleation represents a fundamental materials synthesis paradigm with far-reaching implications for controlling microstructure and properties in multicomponent systems. The experimental and theoretical evidence summarized in this technical guide demonstrates that nucleation frequently proceeds through non-equilibrium pathways involving compositionally distinct intermediates. The recognition that solute drag significantly influences rapid solidification of non-stoichiometric intermetallic compounds [19] provides a crucial theoretical framework for understanding the kinetic limitations of these processes. Furthermore, the identification of multiple nucleation pathways in oxide glass systems [20], including the surface-preferential nucleation of metastable phases, highlights the complex interplay between composition, structure, and nucleation behavior.

These insights create exciting opportunities for materials design across diverse applications. In pharmaceutical development, controlled nonstoichiometric nucleation could enable precise crystal engineering of active ingredients with optimized bioavailability and stability. For advanced functional materials, understanding nonstoichiometric nucleation pathways facilitates the design of nanocrystals with tailored architectures and enhanced properties. Future research directions should focus on developing in situ characterization techniques to directly observe nucleation events, creating multi-scale modeling approaches that bridge atomic-scale simulations with macroscopic kinetics, and exploring how external fields (electric, magnetic, mechanical) can modulate nonstoichiometric nucleation pathways. By harnessing the principles outlined in this guide, researchers can advance from empirical materials synthesis to precisely controlled architectural control of multicrystalline materials.

The Role of Surface Energy and Interfacial Forces in Early-Stage Nucleation

Nucleation, the initial process by which a new phase emerges from a parent phase, represents a fundamental phenomenon in materials science, chemistry, and biology. The critical role of surface energy and interfacial forces in governing early-stage nucleation mechanisms has become increasingly apparent through recent research advances. When the first stable nuclei form, their creation necessitates the development of an interface, making the associated surface energy a dominant factor in determining the thermodynamic barrier to nucleation [21].

This whitepaper examines how interfacial phenomena control nucleation pathways and outcomes within the broader context of nanocrystal formation and growth mechanisms research. The precise manipulation of nucleation is paramount for technological applications ranging from pharmaceutical development to the synthesis of advanced nanomaterials. For drug development professionals, controlling polymorphic forms through nucleation conditions can determine critical product characteristics including bioavailability, stability, and manufacturing reproducibility [22] [23]. Recent experimental and computational breakthroughs now provide unprecedented insight into how interfacial properties dictate nucleation behavior across diverse systems from metallic nanocrystals to gas hydrates and organic compounds.

Theoretical Foundation

Classical Nucleation Theory and Surface Energy

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) provides the fundamental framework for understanding early-stage nucleation. CNT describes nucleus formation through a balance of volume and surface energy terms [21]. The free energy of formation (ΔG) for a spherical nucleus of radius r is given by:

ΔG = (4/3)πr³ΔGv + 4πr²γ

where ΔGv is the Gibbs free energy change per unit volume (driving force for phase transition), and γ is the surface free energy per unit area (resistance to interface creation) [21]. The concept of a critical nucleus emerges from this relationship—a cluster that must attain sufficient size to overcome the maximum free energy barrier (ΔG*) before stable growth can proceed.

Despite its utility, CNT has recognized limitations, particularly in accurately predicting nucleation rates, which can deviate from experimental observations by orders of magnitude [21]. These discrepancies often stem from CNT's treatment of the nucleus as a bulk phase with sharply defined interfaces and its limited ability to account for complex interfacial chemistries and non-classical nucleation pathways.

Extensions to CNT for Heterogeneous Systems

In heterogeneous nucleation, the presence of foreign interfaces modifies the nucleation barrier by introducing additional interfacial energy terms. The contact angle (θ) between the nucleating phase and substrate directly determines nucleation potency through the wetting angle factor f(θ):

f(θ) = (2 - 3cosθ + cos³θ)/4

This relationship explains why substrates that are well-matched to the crystal structure of the nucleating phase (low contact angle) dramatically reduce the energy barrier for nucleation [24]. For gas hydrates in porous media, this framework has been extended to account for complex interface geometries including concave surfaces and triple-phase boundary lines, demonstrating how substrate curvature either enhances or suppresses nucleation probability depending on wettability [24].

Table 1: Thermodynamic Influence of Interface Geometry on Nucleation Barrier

| Interface Geometry | Effect on Nucleation Barrier | Governing Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Planar Surface | Moderate reduction | Contact angle, interfacial energies |

| Concave Surface | Significant reduction (hydrophilic) | Radius of curvature, contact angle |

| Convex Surface | Barrier increase | Radius of curvature, contact angle |

| Triple-Phase Boundary | Maximum reduction | Line tension, interfacial energies |

Experimental Evidence Across Material Systems

Nanocrystal Formation: Competing Pathways

Recent research on zinc oxide (ZnO) nanocrystal formation reveals how surface energy considerations dictate complex nucleation behavior. Advanced machine-learning force fields that incorporate long-range interactions have enabled atomistic simulations demonstrating temperature-dependent competition between different nucleation pathways [22]. At moderate supercooling, nucleation follows the classical single-step pathway to the stable wurtzite (WRZ) structure. In contrast, under high supercooling conditions, a multi-step process emerges involving metastable body-centered tetragonal (BCT) phases [22].

This pathway competition stems from the relative surface energies of different crystal polymorphs at nanoscale dimensions. While WRZ is the most stable bulk polymorph, BCT becomes increasingly favored at sufficiently small nanoparticle sizes due to its superior surface energy characteristics [22]. These findings highlight the necessity of computational approaches that accurately capture surface and interfacial interactions when predicting nanocrystal formation mechanisms.

Table 2: Surface Energy Effects on ZnO Nanocrystal Polymorph Stability

| Polymorph | Bulk Stability | Nanoparticle Stability | Dominant Surface Planes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wurtzite (WRZ) | Most stable | Less favorable at small sizes | Nonpolar and polar surfaces |

| Body-Centered Tetragonal (BCT) | Less stable | More favorable at small sizes | Primarily nonpolar surfaces |

| Zinc Blende (ZBL) | Metastable | Moderate stability | Polar (111) facets |

Interfacial Concentration Effects in Molecular Systems

The traditional assumption that solute concentration near interfaces equals bulk concentration has been challenged by glycine nucleation studies. Molecular dynamics simulations demonstrate that hydrophobic interfaces (e.g., oil-solution) significantly enhance local glycine concentration, while hydrophilic interfaces (e.g., air-solution) deplete concentration [23]. This interfacial concentration effect facilitates heterogeneous nucleation even in the absence of specific chemical interactions or epitaxial matching.

For glycine aqueous solutions, the presence of a tridecane (oil) layer dramatically accelerated nucleation compared to air-solution interfaces, despite the nonpolar, hydrophobic nature of tridecane being seemingly incompatible with highly polar, hydrophilic glycine molecules [23]. This counterintuitive result underscores the importance of dispersion interactions in creating localized concentration gradients that drive nucleation kinetics, revealing a mechanism distinct from traditional explanations based on chemical functionality, templating, or confinement effects.

Electrochemical Nucleation and Surface Energy Control

In situ visual observation of copper nanocrystal electrodeposition has provided direct evidence for surface energy-controlled nucleation mechanisms. The surface energy of the electrode substrate profoundly influences both nucleation probability and the resulting crystal structure [25]. High-energy electrodes promote strong interphase interactions, reducing nucleation barriers and facilitating polycrystalline formation. Conversely, low-energy interfaces yield monocrystalline structures through different interfacial dynamics [25].

These surface energy differences produce measurable functional consequences. High-energy interfaces reduce crystal layer thickness by 30.92-52.21% and enhance charge transfer capability by 19.18-31.78%, promoting uniform, compact films with superior stability for long-duration electrodeposition [25]. This direct relationship between substrate surface energy and nanocrystal characteristics enables strategic manipulation of nucleation outcomes for applications in resource recovery and nanomaterial synthesis.

Interfacial Segregation in Metallic Alloys

In metallic systems, deliberate interfacial segregation of alloying elements provides a powerful approach to manipulating nucleation potency. Atomic-scale characterization reveals that alloying elements in liquid melts segregate to interfaces, forming two-dimensional compounds (2DCs) or solutions (2DSs) that dramatically alter substrate performance [26].

For example, in Al-Ti-B grain refiners, an Al₃Ti 2DC layer forms on TiB₂ substrate surfaces, creating the actual nucleation interface for α-Al rather than TiB₂ itself [26]. This interfacial segregation explains the extreme nucleation potency of these systems. Similarly, specific elements can impair nucleation potency through segregation—Zr and Si at certain concentrations form Ti₂Zr 2DC or Si-rich 2DS layers at Al/TiB₂ interfaces, causing the "poisoning" effect that diminishes grain refinement efficiency [26]. These findings demonstrate that nucleation potency is not an intrinsic substrate property but rather emerges from complex interfacial chemistry that can be deliberately engineered.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Computational Approaches: Machine-Learning Force Fields

The development of advanced computational methods has been instrumental in elucidating nucleation mechanisms at atomic resolution. For ZnO nanocrystal studies, researchers created a Physical LassoLars Interaction Potential plus point charges (PLIP+Q) model that combines machine-learning for short-range interactions with a scaled point charge model for long-range electrostatics [22].

Validation Protocol:

- Lattice parameter accuracy: Error quantification against density functional theory (DFT) calculations for multiple polymorphs

- Phonon density of states: Comparison of vibrational spectra with DFT references using supercell approaches

- Surface energy reproduction: Assessment of polar, nonpolar, and reconstructed surface energies against DFT benchmarks

- Nanostructure transferability: Energy error measurement for optimized nanoclusters with varied surface terminations [22]

This approach proved particularly crucial for accurately modeling polar surfaces in nanoparticles, where traditional short-range MLIPs fail dramatically, incorrectly predicting stability ordering and producing spurious simulation results [22].

Experimental Characterization: In Situ Visualization

Real-time observation of nucleation events provides direct mechanistic insights. For electrochemical metal nanocrystal formation, in situ measurements enable correlation of interfacial properties with nucleation outcomes [25].

Experimental Workflow:

- Substrate preparation: Electrodes with controlled surface energies (high-energy vs. low-energy)

- Electrodeposition setup: Three-electrode configuration with controlled potential/current

- In situ monitoring: Real-time visualization of nucleation events

- Ex situ characterization: Raman spectroscopy, electron microscopy, electrochemical analysis

- Structure-property correlation: Linking nucleation behavior to functional performance [25]

Interface Analysis: Advanced Electron Microscopy

Atomic-scale characterization of metal/substrate interfaces reveals how segregation phenomena control nucleation behavior [26].

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Melt filtration: Pressurized argon forces melt through porous ceramic filter

- Particle concentration: Substrate particles collected in region above filter

- Specimen preparation: Traditional metallography followed by FIB lift-out for TEM

- Atomic-scale characterization: Aberration-corrected STEM with EDS/EELS analysis [26]

This methodology enables direct observation of interfacial segregation layers and their crystallographic relationships with both substrate and nucleated phase, providing unprecedented insight into nucleation mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Nucleation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Nucleation Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Machine-Learning Force Fields (PLIP+Q) | Atomistic simulation with long-range interactions | Modeling ZnO nanocrystal polymorph competition [22] |

| TiB₂ Substrate Particles | Heterogeneous nucleation sites for aluminum | Investigating interfacial segregation effects [26] |

| Tridecane (C₁₃H₂₈) | Oil phase for liquid-liquid interface studies | Probing interfacial concentration effects on glycine nucleation [23] |

| Electrode Substrates (Varied Surface Energy) | Controlled interfaces for electrochemical nucleation | Visual observation of Cu nanocrystal formation [25] |

| Aberration-Corrected STEM | Atomic-scale interface characterization | Identifying 2D compounds at metal/substrate interfaces [26] |

Surface energy and interfacial forces constitute dominant factors controlling early-stage nucleation across diverse material systems. The experimental and computational evidence presented demonstrates that nucleation is not merely a stochastic process but can be strategically manipulated through intelligent interface engineering. Key principles emerge: (1) Local interfacial chemistry often differs substantially from bulk composition, creating distinct nucleation environments; (2) Nanoscale surface energy differences can override bulk thermodynamic stability in determining polymorph selection; (3) Interfacial segregation phenomena provide powerful levers for controlling nucleation outcomes.

For drug development professionals, these insights offer new strategies for controlling crystal form selection through careful manipulation of interfacial properties rather than solely through bulk solution conditions. The emerging ability to design interfaces with specific nucleation potencies promises enhanced control over critical pharmaceutical properties including bioavailability, stability, and manufacturing consistency. Future research directions should focus on developing quantitative predictive models that incorporate interfacial chemistry effects and expanding in situ characterization techniques to capture transient nucleation events at higher temporal and spatial resolution.

From Bench to Formulation: Synthesis Methods and Cutting-Edge Drug Delivery Applications

The pursuit of effective strategies for nanocrystal formation is fundamentally rooted in the control over nucleation and growth mechanisms, processes that dictate the critical structural, physical, and chemical properties of the resulting material. For poorly water-soluble Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), which constitute a significant proportion of modern drug candidates, nanocrystal technology has emerged as a pivotal formulation approach to enhance bioavailability by dramatically increasing dissolution rate and saturation solubility [27]. The synthesis of these drug nanocrystals is broadly categorized into two paradigms: top-down and bottom-up approaches [28] [29]. Top-down methods, such as wet media milling (WMM) and high-pressure homogenization (HPH), involve the mechanical breakdown of large drug particles into nanoscale crystals [28]. In contrast, bottom-up techniques, typified by liquid antisolvent precipitation, build nanocrystals from molecular precursors by precipitating a dissolved drug into a nanoscale solid phase [28] [29]. The selection between these pathways is not merely a technical choice but a fundamental decision that influences crystal defects, polymorphic stability, and ultimately, the performance and shelf-life of the final pharmaceutical product. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these core methodologies, framing them within the context of nucleation and growth theory for a research and development audience.

Core Principles: Nucleation and Growth in Nanocrystal Formation

The Classical Nucleation Framework

At the heart of bottom-up nanocrystal formation lies the process of nucleation, where solute molecules in a supersaturated solution aggregate into stable clusters that can grow into crystals. Classical nucleation theory describes this as a homogeneous process where the formation of a new phase is governed by the competition between the bulk free energy (which favors growth) and the surface free energy (which opposes it) [30]. A critical cluster size must be surpassed for the nucleus to become stable and proceed to grow. In metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and by extension molecular crystals, this process can be described by the secondary building unit (SBU) model, where metal clusters act as defined building blocks for subsequent crystal growth [30]. The kinetics of this process are intensely studied using advanced in situ characterization techniques like X-ray scattering and spectroscopy to monitor the early-stage seeds and crystal growth pathways in real-time [30].

Non-Classical Pathways and Top-Down Fragmentation

Beyond the classical model, non-classical nucleation pathways involving intermediate phases such as pre-nucleation clusters or liquid precursors are increasingly recognized as important mechanisms, particularly in complex systems [30]. These pathways can lead to polymorphic competition, as observed in zinc oxide nanoparticles where different nucleation pathways compete depending on the degree of supercooling [22]. In stark contrast, top-down approaches bypass nucleation altogether. They operate on the principle of energetic comminution, applying high mechanical shear forces, collisions, and/or cavitation to fracture bulk crystalline material into nanocrystals [28] [27]. This process does not involve a phase transition but rather the physical disintegration of an existing solid phase.

Detailed Methodological Breakdown

Top-Down Approach: Wet Media Milling (WMM)

Wet Media Milling (WMM) relies on high-shear forces generated by collisions between milling media (beads) and solid API particles to achieve particle size reduction [28] [27].

- Mechanism: The drug suspension is circulated or agitated with fine milling beads. The impaction and shear forces from bead-bead and bead-chamber collisions provide the energy necessary to fracture drug microparticles into nanocrystals.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Formulation: The poorly water-soluble API (e.g., 1-10% w/w loading) is dispersed in an aqueous stabilizer solution. Common steric stabilizers include HPMC (0.5-5% w/w) or PVP K30; electrostatic stabilizers like Sodium Lauryl Sulfate (SLS, 0.1-1% w/w) may also be used [28].

- Milling: The suspension is transferred to a milling chamber filled with milling media (e.g., yttrium-stabilized zirconia beads, 0.3-0.8 mm diameter). The milling chamber is agitated at high speeds (e.g., 1000-3000 rpm) for a defined period (minutes to hours) [28].

- Separation: The milled nanosuspension is separated from the beads using a sieve or filter.

- Key Parameters: Milling time, rotational speed, bead size and material, bead loading, and stabilizer type/concentration are critical process controls. A Box-Behnken design can optimize these parameters, identifying that milling time and speed significantly impact particle size and zeta potential [28].

Top-Down Approach: High-Pressure Homogenization (HPH)

High-Pressure Homogenization (HPH) achieves particle size reduction by forcing a drug suspension through a narrow homogenization orifice under extreme pressure [27].

- Mechanism: Particle size reduction is primarily brought about by cavitation (the formation and implosive collapse of vapor bubbles), and secondarily by high-shear forces and inter-particle collisions [27].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Pre-treatment: A coarse pre-suspension of the drug in stabilizer solution is often required, which may be pre-milled using a high-shear mixer.

- Homogenization: The pre-suspension is cycled through the homogenizer (e.g., 10-30 cycles) at high pressures (500 - 2500 bar). The suspension experiences tremendous velocity and pressure drops as it passes through the homogenizing gap.

- Cooling: Due to significant heat generation, the process typically requires an efficient cooling system to protect heat-sensitive APIs.

- Key Parameters: Homogenization pressure, number of cycles, and stabilizer composition are the primary factors controlling the final particle size.

Bottom-Up Approach: Liquid Antisolvent Precipitation

Liquid Antisolvent Precipitation involves creating a supersaturated environment to induce the nucleation of nanoscale drug particles from a molecular solution [28] [29].

- Mechanism: The drug is dissolved in a water-miscible organic solvent (e.g., acetone, ethanol). This solution is then rapidly injected into a larger volume of an antisolvent (water) containing a stabilizer. The sudden shift in solvent environment creates a high degree of supersaturation, leading to rapid nucleation and the formation of nanocrystals.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Solution Preparation: The drug is dissolved in a suitable organic solvent to create a concentrated solution.

- Stabilizer Dispersion: The stabilizer (e.g., HPMC, PVP, Poloxamers) is dissolved in the aqueous antisolvent phase.

- Precipitation: The drug solution is rapidly added to the antisolvent under controlled mixing conditions (e.g., magnetic stirring or high-shear mixing). The mixture is typically stirred for an additional period to ensure complete solvent diffusion and crystal hardening.

- Solvent Removal: The residual organic solvent is removed by evaporation or dialysis.

- Key Parameters: The drug and stabilizer concentration, solvent-to-antisolvent ratio, mixing speed, and temperature are critical for controlling nucleation kinetics and crystal growth, preventing Ostwald ripening and particle aggregation [28].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflows and fundamental mechanisms of these three primary methods.

Critical Comparison and Data Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The following table summarizes key performance characteristics and experimental outcomes for the three primary nanocrystal production methods, drawing from comparative studies.

| Parameter | Wet Media Milling (WMM) | High-Pressure Homogenization (HPH) | Antisolvent Precipitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Final Particle Size (d90) | ~150-250 nm for Glipizide with PVP K30 [28] | Comparable to WMM, but distribution may differ [27] | ~243 nm for Glipizide with PVP K30 [28] |

| Impact of Stabilizer Type | PVP K30 showed highest particle size reduction [28] | Behavior similar to WMM with changes in stabilizer conc. & type [27] | SLS showed highest particle size reduction [28] |

| Energy Consumption | High (mechanical shear from collisions) [27] | High (high pressure & cavitation) [27] | Low (mixing energy only) |

| Scalability | Ease of scale-up, straightforward technology transfer [28] [27] | Scalable, but miniaturization is less straightforward [28] | Scalability can be challenging due to solvent volume & mixing control [29] |

| Processing Time | Hours (e.g., significantly influenced by milling time) [28] | Fast (process time per cycle is short) [27] | Very fast precipitation, but solvent removal is time-consuming [28] |

| Key Process Parameters | Milling time, milling speed, bead size & loading [28] | Homogenization pressure, number of cycles [27] | Solvent/antisolvent ratio, mixing intensity, stabilizer/drug ratio [28] |

| Primary Mechanisms | Shear forces, impaction [27] | Cavitation, shear, collisions [27] | Supersaturation, nucleation kinetics [29] |

Impact on Material and Stability Attributes

The choice of synthesis method profoundly affects critical quality attributes of the nanocrystals beyond mere size.