Nanobiosensors vs. Traditional Diagnostics: A New Paradigm in Accuracy for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the transformative role of nanobiosensors in diagnostic accuracy.

Nanobiosensors vs. Traditional Diagnostics: A New Paradigm in Accuracy for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the transformative role of nanobiosensors in diagnostic accuracy. It explores the foundational principles of nanobiosensors, detailing their operation and the nanomaterials that enhance their function. The review covers diverse methodological applications across oncology, neurodegenerative diseases, and infectious diseases, highlighting their integration into point-of-care systems. It critically addresses current challenges in fabrication and standardization while presenting a rigorous comparative validation against traditional techniques like ELISA and PCR. The synthesis concludes that nanobiosensors offer a significant leap in sensitivity, specificity, and speed, paving the way for personalized medicine and advanced clinical diagnostics.

The Foundation of Nanobiosensors: Principles and Core Components

Nanobiosensors represent a transformative class of analytical devices that synergistically integrate biological recognition elements with nanotechnology-enabled transducers. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a biosensor is a device that uses specific biochemical reactions mediated by isolated enzymes, immune systems, tissues, or organelles to detect chemical compounds through optical, thermal, or electrical signals [1]. The evolution into nanobiosensors involves the application of nanomaterials and nanoscale engineering principles to create systems with significantly enhanced sensitivity, specificity, and operational characteristics. These devices are fundamentally characterized by their ability to detect biological markers (BioMKs) linked with various disease states with exceptional precision, addressing critical limitations of traditional diagnostic methods such as truncated sensitivity, stunted specificity, and cumbersome operational procedures [2].

The architectural foundation of a nanobiosensor consists of two primary components: a biological recognition element and a nanotechnology-based transducer. The biological element, which can include enzymes, antibodies, DNA/RNA probes, or whole cells, provides the mechanism for specific target interaction. The transducer, enhanced with nanomaterials such as nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), quantum dots (QDs), or nanowires, converts this biological interaction into a quantifiable electronic, optical, or acoustic signal [2] [1]. This integration has propelled innovations across medical diagnostics, with applications ranging from continuous intravascular monitoring of physiological parameters to early-stage detection of cancers and infectious diseases [3]. The burgeoning market interest is reflected in the estimated biosensor market size of USD 30.25 billion in 2024, with a projected compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.7% from 2025 to 2034, underscoring the significant impact of these technologies [3].

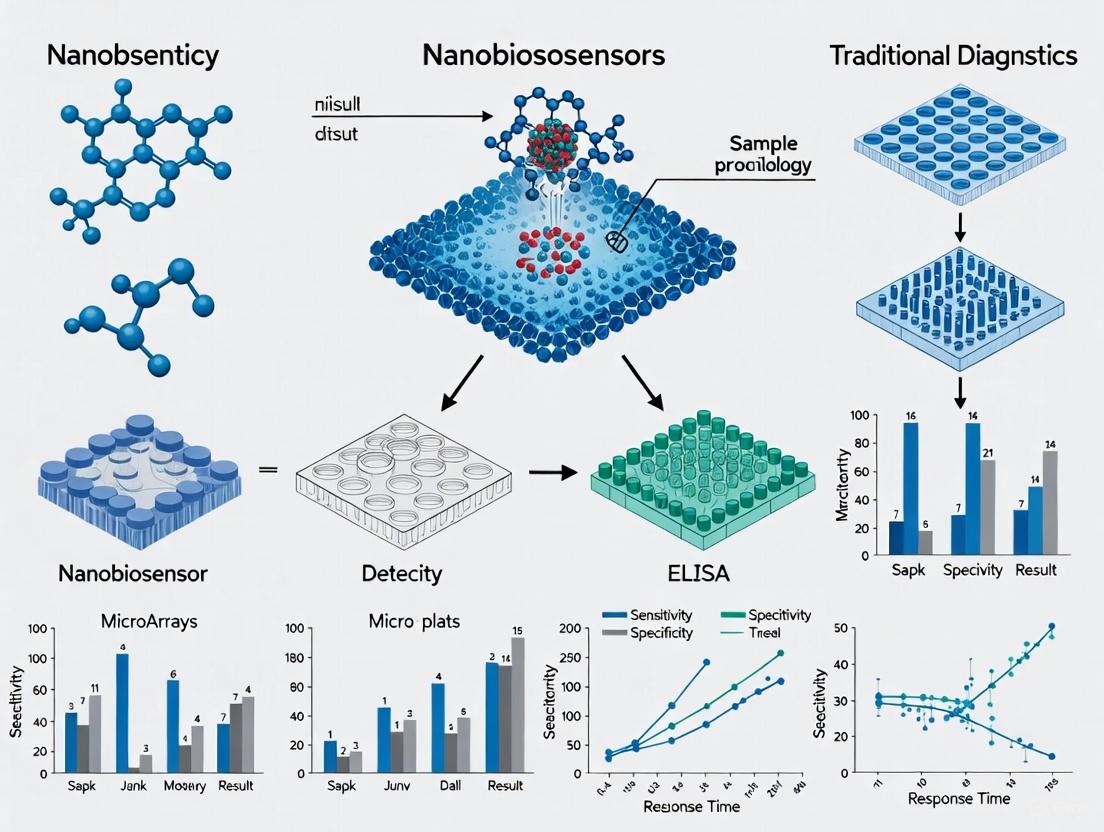

Comparative Analysis: Nanobiosensors vs. Traditional Diagnostics

The diagnostic performance of nanobiosensors substantially surpasses that of traditional methods across multiple parameters, including sensitivity, specificity, response time, and potential for miniaturization. The defining advantage stems from the nanoscale interface, which offers a dramatically increased surface-to-volume ratio, enhancing the density of biorecognition events and improving signal transduction efficiency [2] [1].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Diagnostic Modalities

| Performance Parameter | Traditional Diagnostics | Nanobiosensors | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Truncated sensitivity (e.g., microscopic procedures) [2] | Exceptionally high; capable of detecting single biomolecules [1] | Detection of cellular miRNA in colorectal cancer; identification of single biomarkers [2] |

| Specificity | Susceptible to interference; stunted specificity [2] | High specificity via precise biorecognition (e.g., antibody-antigen, DNA hybridization) [1] | Functionalized nanoparticles for specific pathogen detection [2] |

| Response Time | Often lengthy (e.g., culture tests taking weeks) [4] | Rapid, real-time monitoring (minutes vs. weeks) [4] [3] | Intravascular glucose sensors providing real-time data [3]; molecular PCR diagnostics cutting wait time by up to four weeks versus culture [4] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Generally limited to single-analyte detection | High potential for simultaneous detection of multiple analytes [2] | Use of multiplex PCR assays for identifying multiple resistance mutations [4] |

| Miniaturization & Portability | Cumbersome equipment; mostly confined to laboratories [2] | High degree of miniaturization; enables point-of-care testing (POCT) [4] [3] | Implantable intravascular biosensors for continuous monitoring [3]; expansion of POCT in remote areas [4] |

A critical application demonstrating this performance leap is in glucose monitoring for diabetes management. While traditional methods require frequent, invasive blood sampling with delayed results, electrochemical implantable biosensors, including subcutaneous or intravascular variants, provide real-time glucose level data, enabling precise therapy adjustments [3]. A study utilizing the GluCath System—an intravascular continuous glucose monitoring system based on a chemical fluorescence quenching mechanism—demonstrated acceptable accuracy during 48-hour placement in critically ill patients, a scenario where both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia can lead to adverse outcomes [3].

Furthermore, the emergence of non-invasive liquid biopsies for early cancer detection represents another area where nanobiosensors outperform traditional tissue biopsies. These nanobiosensor-based liquid biopsies analyze blood samples to detect cancers earlier than traditional methods, offering a safer, less invasive alternative to surgical procedures [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Fabrication of an Electrochemical Nanobiosensor for Glucose Detection

This protocol details the development of an implantable electrochemical glucose sensor, a technology that has been validated in clinical studies for continuous monitoring [3].

1. Reagent Preparation:

- Glucose Oxidase and Catalase: Immobilize these enzymes within a specialized polymer membrane. Glucose oxidase catalyzes the oxidation of glucose, while catalase is often co-immobilized to break down the resulting hydrogen peroxide, mitigating its interfering effects and improving sensor longevity [3].

- Nanomaterial-functionalized Electrode: Prepare a working electrode by functionalizing its surface with nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes or gold nanoparticles. This step increases the electroactive surface area, enhances electron transfer rates, and improves the stability of the immobilized enzymes [2] [1].

2. Sensor Assembly and Transduction Mechanism:

- Integrate the enzyme-immobilized membrane with the nanomaterial-functionalized oxygen electrode. The operational principle is based on the electrochemical detection of oxygen consumption. As glucose diffuses into the membrane and is oxidized by glucose oxidase, local oxygen is consumed. The oxygen electrode transduces this change in oxygen concentration into a quantifiable amperometric signal (current) that is proportional to the glucose concentration [3].

- Assemble the sensor with a reference electrode and a counter electrode to form a complete three-electrode electrochemical cell. The entire assembly is then integrated with a miniaturized telemetry system for wireless data transmission from the implant site [3].

3. Calibration and Validation:

- Calibrate the sensor response in vitro using standard glucose solutions across a physiologically relevant range (e.g., 50-400 mg/dL).

- Validate sensor performance in vivo by comparing the sensor's telemetry signal with reference blood glucose values measured using standard laboratory techniques. A mathematical model is often applied to describe the dynamic relationship between blood glucose and the sensor signal in the tissue [3].

Protocol 2: Development of an Optical Nanobiosensor for Liquid Biopsy

This protocol outlines the creation of a nanobiosensor for detecting cancer biomarkers in blood serum, a key application in the trend toward liquid biopsies [4].

1. Surface Functionalization:

- Functionalization with Antibodies: A optical fiber or waveguide is coated with a nanomaterial (e.g., gold nanoparticles or graphene) to enhance its evanescent field and surface plasmon resonance properties. The surface is then functionalized with specific monoclonal antibodies that act as capture probes for a target cancer biomarker (e.g., prostate-specific antigen or circulating tumor DNA) [2] [1].

2. Sample Incubation and Binding:

- A serum sample from a patient is introduced to the functionalized sensor surface and allowed to incubate. Target biomarkers present in the sample will bind specifically to the immobilized antibodies.

3. Signal Generation and Detection:

- Label-based Detection: A secondary antibody, conjugated with a fluorescent nanomaterial (e.g., quantum dots), is introduced. This antibody binds to the captured biomarker, forming a "sandwich" complex. The excitation of the quantum dots results in a fluorescence signal whose intensity is proportional to the biomarker concentration [1].

- Label-free Detection: The binding of the biomarker to the sensor surface directly alters the local refractive index. This change is detected as a shift in the resonance angle of a surface plasmon resonance (SPR) setup or a wavelength shift in a fiber Bragg grating, providing a quantitative measure of the biomarker without the need for secondary labels [2] [1].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The core functionality of a nanobiosensor can be visualized as a sequential process involving molecular recognition and signal transduction. The following diagram illustrates this generalized workflow, which is common to many nanobiosensor designs.

Diagram 1: Generalized workflow of a nanobiosensor.

For electrochemical biosensors, which are widely used for continuous monitoring of metabolites like glucose, the process involves a specific biochemical reaction that generates an electrical current.

Diagram 2: Electrochemical glucose nanobiosensor mechanism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The development and operation of high-performance nanobiosensors rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The table below details several key components and their critical functions in experimental setups.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nanobiosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Nanobiosensors | Specific Examples & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticles (NPs) | Signal amplification; carrier for biorecognition elements; enhance conductivity and catalytic activity. | Au NPs for colorimetric sensors; magnetic NPs for separation and detection [2]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Transducer element; provide high electrical conductivity and large surface area for biomolecule immobilization. | Used in electrochemical sensors to enhance electron transfer and sensitivity [1]. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Fluorescent labels; provide high photostability and tunable emission wavelengths for multiplexed optical detection. | QD-antibody conjugates for fluorescent immunoassays and bioimaging [1] [3]. |

| Enzymes | Biological recognition element; catalyze specific reactions with the target analyte to generate a detectable product. | Glucose oxidase for glucose sensors; horseradish peroxidase used in enzyme-linked assays [2] [3]. |

| Antibodies/Aptamers | Biological recognition element; provide high specificity and affinity for binding to target antigens or molecules. | Monoclonal antibodies for immunoassays; DNA/RNA aptamers as synthetic recognition elements [2] [1]. |

| Functionalized Surfaces | Platform for immobilizing biorecognition elements; ensure stability and proper orientation of biomolecules. | SAMs (Self-Assembled Monolayers) on gold surfaces; polymer membranes for enzyme encapsulation [2] [3]. |

The integration of nanotechnology with biological recognition principles has unequivocally given rise to a new generation of diagnostic tools. As the comparative data and experimental protocols in this guide demonstrate, nanobiosensors objectively surpass traditional diagnostic methods in critical performance metrics such as sensitivity, speed, and miniaturization potential. These devices are poised to fundamentally reshape diagnostic paradigms, enabling a shift from centralized, delayed testing to decentralized, real-time, and personalized health monitoring. The ongoing research and development, particularly in areas like intravascular biosensors, liquid biopsies, and point-of-care devices, underscore a clear trajectory toward more integrated, intelligent, and accessible healthcare solutions. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering the materials, methods, and principles behind nanobiosensors is not merely an academic exercise but a necessary step toward actively participating in and driving the future of medical diagnostics.

At the heart of every biosensor lies a fundamental principle: the specific interaction between a biological recognition element (bioreceptor) and a target analyte, which is subsequently transformed into a quantifiable signal [3] [1]. This process bridges the biological and digital worlds, enabling the detection and measurement of substances ranging from simple ions to complex proteins and whole cells. Biosensors are defined as analytical instruments that measure variations in biological activity and transform them into quantifiable electronic signals [3]. The evolution of this technology, particularly with the integration of nanotechnology, has revolutionized diagnostics by enhancing sensitivity, specificity, and miniaturization far beyond the capabilities of traditional methods [1] [5].

The core architecture of a biosensor universally comprises two essential components: a bioreceptor that facilitates specific interaction with the target analyte, and a transducer that converts this biological event into a measurable electrical, optical, or other physical signal [1]. This review provides a systematic comparison of the working principles, performance metrics, and experimental methodologies of various biosensor classes, with a specific focus on the transformative impact of nanotechnology in enhancing diagnostic accuracy.

Core Components and Working Principles

The Bioreceptor-Target Interaction

The initial and most critical step in biosensing is the specific molecular recognition between the bioreceptor and the target analyte. This interaction confers the sensor's selectivity. Common bioreceptors and their binding mechanisms include:

- Enzymes: Catalyze specific biochemical reactions, with the reaction rate proportional to the analyte concentration [1].

- Antibodies: Bind to specific antigens (e.g., proteins, pathogens) with high affinity through immunocomplex formation [5].

- Nucleic Acids (DNA/RNA): Hybridize with complementary sequences, enabling the detection of genetic markers, mutations, or pathogens [1] [5].

- Whole Cells and Tissues: Utilize inherent metabolic pathways or receptor functions for detection [1].

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow of a biosensor, from analyte binding to signal output.

Diagram 1: The core signal transduction pathway in a biosensor.

Transduction Mechanisms: Converting Biology to Signal

Following the biorecognition event, a physicochemical change (e.g., electron transfer, mass change, photon emission) occurs. The transducer detects this change and converts it into an analyzable signal. The principal transduction mechanisms are compared below:

- Electrochemical: Measures electrical properties (current, potential, impedance) resulting from the biological interaction. These are highly sensitive and compatible with miniaturization [3] [1].

- Optical: Detects changes in light properties (wavelength, intensity, polarization) using techniques like fluorescence, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), or Raman scattering (e.g., SERS) [3] [5].

- Acoustic: Utilizes sound waves; the binding of mass to the sensor surface alters the frequency of acoustic wave devices (e.g., Quartz Crystal Microbalance - QCM) [3].

- Thermal: Measures the heat absorbed or released during a biochemical reaction using thermistors [3].

Performance Benchmarking: Nanobiosensors vs. Traditional Diagnostics

The integration of nanomaterials such as nanoparticles, nanotubes, quantum dots, and nanowires has profoundly enhanced the performance characteristics of biosensors [1] [6]. The table below provides a quantitative and qualitative comparison of key diagnostic approaches.

Table 1: Performance comparison of diagnostic sensor technologies

| Parameter | Traditional Diagnostics (e.g., ELISA, Standard Electrodes) | Modern Nanobiosensors | Experimental Basis & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Low to moderate (μM-mM range) | Very High (pM-fM range) | Nanomaterials provide a large surface area, enhancing response to low-abundance biomarkers [1] [5]. |

| Specificity | Moderate; susceptible to cross-reactivity | Very High | High specificity of bioreceptors combined with nanomaterial-enhanced signal-to-noise ratio reduces false positives [5]. |

| Response Time | Minutes to hours (e.g., 1-4 hours for ELISA) | Seconds to minutes | Nanostructures facilitate faster mass transfer and catalytic activity, enabling real-time monitoring [1]. |

| Miniaturization Potential | Low | Very High | Nanoscale components enable implantable and wearable form factors (e.g., intravascular biosensors) [3] [1]. |

| Multiplexing Capability | Low (typically single analyte) | High | Nanostructured arrays (e.g., Au@SiO₂) allow simultaneous detection of multiple analytes on a single platform [5]. |

| Accuracy (Example: IL-6 Detection) | Standard ELISA: Reference value | AuNP/THI Immunosensor: Excellent correlation with ELISA results [5] | A novel label-free electrochemical immunosensor using gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) demonstrated successful detection of Interleukin-6 (IL-6) in patient blood samples, showing high agreement with the standard ELISA method [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Nanobiosensor Types

Protocol: SERS-based Biosensor for Telomerase Activity

This protocol details the construction of a surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) biosensor for ultra-sensitive analysis of telomerase activity, used for early cancer diagnosis [5].

1. Sensor Fabrication:

- Substrate Preparation: A single-layer SiO₂ colloidal crystal film is self-assembled by vertical evaporation. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are then adsorbed onto this film via electrostatic adsorption to create an ordered Au@SiO₂ array substrate.

- Probe Immobilization: The Au@SiO₂ array is functionalized with hairpin DNA2 (hpDNA2) to serve as the capture substrate. Separately, SERS probes are prepared by labeling Au-Ag nanocages (Au-AgNCs) with a Raman reporter molecule and hairpin DNA1 (hpDNA1).

2. Assay Procedure:

- Telomerase Extension: The sample containing telomerase and deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) is applied. Telomerase primers elongate to form long-strand DNA containing repetitive sequences (TTAGGG).

- Dual DNA Amplification: The elongated product triggers a Strand Displacement Amplification (SDA) reaction. The SDA product then initiates a Catalytic Hairpin Assembly (CHA) reaction, bringing the SERS probes (Au-AgNCs) into close proximity with the capture substrate (Au@SiO₂ array).

- Signal Generation & Readout: The assembly of metallic nanostructures creates "hot spots" that dramatically enhance the local electromagnetic field, leading to a significantly amplified SERS signal. The intensity of this signal is quantitatively correlated with telomerase activity.

The following diagram outlines this complex experimental workflow.

Diagram 2: Workflow for a SERS-based telomerase activity assay.

Protocol: Electrochemical Immunosensor for Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

This protocol describes the development of a label-free electrochemical immunosensor for the rapid and sensitive detection of IL-6, a key inflammatory biomarker [5].

1. Sensor Fabrication:

- Electrode Modification: A platinum carbon electrode is modified with gold nanostructures (e.g., Au nanospheres, AuNPs/THI) to create a high-surface-area platform that enhances electron transfer and provides sites for antibody immobilization.

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: IL-6 antibodies are fixed onto the nano-structured electrode surface. In one approach, 4-mercaptobenzoic acid is used as a linker to anchor antibodies to the gold nanoparticles [5].

2. Assay Procedure:

- Incubation: The functionalized electrode is incubated with the sample (e.g., patient serum). IL-6 antigens specifically bind to the immobilized antibodies.

- Label-Free Detection: The binding event directly alters the interfacial properties of the electrode (e.g., charge transfer resistance or capacitance), which is measured without the need for a secondary enzyme label.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Techniques such as electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) or voltammetry are employed to quantify the change in the electrical signal, which is proportional to the IL-6 concentration in the sample. This sensor has been successfully validated against the standard ELISA method using patient blood samples [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The fabrication and operation of high-performance nanobiosensors rely on a suite of specialized materials and reagents. The following table details key components and their functions in typical experiments.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for nanobiosensor development

| Material/Reagent | Function in Biosensing | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal amplification; biocompatible platform for bioreceptor immobilization; enhances electron transfer in electrochemical sensors [6] [5]. | Used in SERS substrates and electrochemical immunosensors for IL-6 detection [5]. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Fluorescent labels with high brightness and photostability; size-tunable emission wavelengths [3] [1]. | Multiplexed detection of biomarkers via distinct fluorescent colors. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Enhance electrical conductivity in electrochemical sensors; high surface area for analyte loading [1]. | Used for creating highly sensitive enzyme-based or DNA-based electrochemical sensors. |

| Specific Bioreceptors (Antibodies, DNA) | Molecular recognition element that provides high specificity for the target analyte [1]. | Antibodies for protein detection (e.g., IL-6); DNA probes for genetic marker detection [5]. |

| Enzymes (e.g., Glucose Oxidase) | Biological catalyst that generates a measurable product (e.g., H₂O₂) upon interaction with the analyte [3] [1]. | Core recognition element in continuous glucose monitoring systems [3]. |

The fundamental working principle of a biosensor—from specific bioreceptor interaction to signal transduction—provides a versatile framework for analytical science. The integration of nanotechnology has decisively shifted the performance benchmarks, enabling nanobiosensors to achieve superior sensitivity, speed, and multiplexing capabilities compared to traditional diagnostic methods. Experimental data from advanced platforms, such as SERS-based sensors for telomerase and electrochemical immunosensors for IL-6, consistently demonstrate this enhanced accuracy and their growing potential for clinical translation. While challenges such as biocompatibility, long-term stability, and standardized manufacturing remain active areas of research, the continued development of novel nanomaterials and sophisticated bioreceptor engineering promises to further solidify the role of nanobiosensors in the future of precise molecular diagnosis and personalized medicine.

The evolution of biosensor technologies is revolutionizing modern healthcare, shifting the paradigm from traditional diagnostic methods towards real-time, continuous monitoring and personalized medicine [3]. Central to this transformation are nanomaterials—gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), quantum dots (QDs), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and graphene. Their integration into biosensing platforms addresses critical limitations of conventional diagnostics, such as poor sensitivity for low-concentration biomarkers, inability for real-time monitoring, and lengthy processing times. For instance, traditional techniques like Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for biomarker detection are specialized and time-intensive, limiting real-time disease progression monitoring [7]. Nanomaterials, with their high surface-to-volume ratio, exceptional electrical properties, and tunable surface chemistry, enable the development of biosensors with unprecedented sensitivity, specificity, and form factor, paving the way for devices capable of detecting targets from glucose to female hormones, which are present in concentrations millions of times lower [8]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these key nanomaterials, focusing on their performance in biosensing applications within the broader research context of nanobiosensors versus traditional diagnostic accuracy.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Nanomaterials

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and performance metrics of the four key nanomaterials in biosensing applications, based on recent experimental findings.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Key Nanomaterials in Biosensing

| Nanomaterial | Key Biosensing Properties | Reported Performance & Experimental Data | Common Functionalization Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | High biocompatibility, strong Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), easy functionalization, size/shape-dependent optical properties [9]. | - AI-integrated AuNP biosensors reduce false positives by 40% [10].- Enable optical imaging resolution down to 10 nm [10].- Provide rapid, non-invasive pathogen detection with 95% accuracy within 30 minutes [10]. | Conjugation with antibodies, aptamers, and DNA; formation of core-shell structures with polymers [9]. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Carbon QDs (CQDs): Low toxicity, tunable photoluminescence, excellent biocompatibility, eco-friendly [11] [12].Graphene QDs (GQDs): Higher surface area, superior carrier mobility, smaller bandgaps than CQDs [13]. | - CQDs function as effective photoelectrodes, absorbing visible and near-infrared light [13].- GQD-based nanohybrids demonstrate better hydrogen evolution rates and catalytic efficiency than CQD-based materials [13].- GQDs as co-catalysts improved photocurrent densities by up to 8.8 times compared to CQD co-catalysts [13]. | Doping (e.g., nitrogen), surface passivation with PEG or PEI, combination with other nanomaterials in hybrids [13] [11]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | High carrier mobility, ballistic electron transport, large surface-to-volume ratio, nanoscale dimensions [14]. | - Single-Walled CNT (SWCNT) sensors enable real-time monitoring of Nitric Oxide (NO), a key inflammatory biomarker for Osteoarthritis [7].- SWCNTs functionalized with (AT)15-ssDNA show specific fluorescence quenching in response to NO concentration [7].- Chirality-pure (6,5) CNTs show higher dopamine adsorption efficiency than (6,6) CNTs, crucial for low-concentration sensing [8]. | Non-covalent wrapping with ssDNA, functionalization with specific polymers, antibody conjugation [14] [7]. |

| Graphene | Exceptional electrical conductivity, high mechanical strength, atomic thickness, large surface area, tunable surface chemistry [15]. | - Graphene Field-Effect Transistors (GFETs) enable real-time, label-free detection of DNA, proteins, and gases [15].- Enhances Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) sensitivity due to strong light-matter interaction [15].- Graphene-based electrodes in electrochemical sensors support rapid electron transfer and fast response times [15]. | π–π stacking, covalent bonding with bioreceptors (antibodies, aptamers), use of derivatives like GO and rGO [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Nanomaterial-Based Detection

Protocol 1: Real-Time Monitoring of Nitric Oxide with SWCNT Biosensors

This protocol details the methodology for using ssDNA-functionalized Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs) to detect nitric oxide (NO), a key inflammatory biomarker, as described in recent research [7].

- Primary Objective: To enable real-time, wireless optical monitoring of NO concentrations in biological environments for early diagnosis and management of inflammatory conditions like osteoarthritis.

- Materials & Reagents:

- SWCNTs: Serve as the fluorescent transducer element.

- (AT)15 Single-Stranded DNA (ssDNA): Used to suspend and functionalize SWCNTs, providing selectivity for NO.

- Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) Hydrogel: Acts as a biocompatible matrix to immobilize the sensor.

- Poly-(Methyl Methacrylate) (PMMA): Used as the substrate for the implantable sensor tag.

- Custom Optical Reader: A device with 657 nm and 726 nm LEDs for excitation and a sensitive SWIR camera for detecting the fluorescence emission of SWCNTs (~900-1400 nm).

- Methodology:

- Sensor Preparation: SWCNTs are suspended and non-covalently functionalized with (AT)15 ssDNA nucleotide sequences. This coating confers selectivity for NO.

- Immobilization: The ssDNA-SWCNT complex is uniformly embedded within a GelMA hydrogel to create a stable, biocompatible sensing layer.

- Tag Integration: The ssDNA-SWCNT:GelMA sensor is integrated into a tiny, implantable PMMA tag.

- Optical Sensing: The implanted tag is excited by the external optical reader. Upon binding of NO, the SWIR fluorescence of the SWCNTs is selectively quenched.

- Quantification: The degree of fluorescence quenching is measured and correlated with the concentration of NO in the surrounding environment.

- Key Experimental Workflow:

Protocol 2: Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Sensing with Graphene Quantum Dots

This protocol outlines the use of Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) to significantly enhance the performance of photoelectrochemical (PEC) systems, such as those used for water splitting and biomarker detection [13].

- Primary Objective: To leverage the superior properties of GQDs over CQDs to improve light absorption, charge separation, and catalytic activity in PEC biosensing platforms.

- Materials & Reagents:

- Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs): Act as a co-catalyst and sensitizer.

- Semiconductor Photoelectrode (e.g., TiO₂): Serves as the primary photoactive material.

- Nitrogen Dopant Precursor: Used to introduce nitrogen atoms into the GQD structure to enhance electrocatalytic activity.

- PEC Cell: A standard electrochemical cell equipped with a light source and electrodes.

- Methodology:

- Synthesis & Doping: GQDs are synthesized via a bottom-up approach (e.g., from citric acid) or top-down method. They are subsequently doped with nitrogen to create more active sites.

- Nanohybrid Formation: The N-doped GQDs are composited with the semiconductor photoelectrode (e.g., TiO₂) to form a nanohybrid material.

- PEC Testing: The GQD-semiconductor photoelectrode is assembled in a PEC cell. Upon illumination, the GQDs enhance light absorption, particularly in the visible spectrum.

- Performance Measurement: The photocurrent density generated is measured. GQDs act as electron reservoirs, reducing the recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs and leading to a significantly higher photocurrent.

- Key Experimental Workflow:

Signaling Pathways and Sensing Mechanisms

The superior performance of nanobiosensors is rooted in the distinct physical mechanisms through which they transduce a biological binding event into a quantifiable signal. The following diagram illustrates the primary signaling pathways for the featured nanomaterials.

Table 2: Core Sensing Mechanisms in Nanobiosensors

| Nanomaterial | Primary Sensing Mechanism | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles | Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) | Oscillation of conduction electrons at the nanoparticle surface upon light excitation, which shifts upon analyte binding [9]. |

| Quantum Dots | Photoluminescence Modulation | Changes in fluorescence intensity or wavelength due to energy/electron transfer processes or direct binding to the QD surface [13] [11]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes | Fluorescence Quenching / Electrochemical Gating | In optical sensors, fluorescence quenching by charge transfer (e.g., NO detection). In FETs, analyte binding alters the local electrostatic potential, modulating conductivity [14] [7]. |

| Graphene | Field-Effect Modulation / Electrochemical Transfer | In GFETs, analyte binding directly dopes the graphene channel, changing its electrical resistance and enabling label-free detection [15]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers developing nanobiosensors, the following reagents and materials are fundamental for fabricating and functionalizing these advanced sensing platforms.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Nanobiosensor Development

| Item Name | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs) | The core transducer material for optical and electrochemical sensors; requires separation/purification by chirality for optimal performance [14] [8]. |

| Specific ssDNA Sequences (e.g., (AT)15) | Used to non-covalently functionalize and suspend SWCNTs, providing selectivity for target analytes like nitric oxide [7]. |

| Graphene Oxide & Reduced Graphene Oxide | Graphene derivatives with abundant oxygen groups for easy functionalization with bioreceptors, widely used in composite sensors and electrodes [15]. |

| Gold Nanospheres, Nanorods, & Nanostars | Spherical particles are common, but shapes with high surface area (nanorods, nanostars) offer superior sensitivity and are preferred for sensor modification [9]. |

| Polyethyleneimine & PEG | Polymers used for surface passivation of Quantum Dots and CNTs to improve solubility, stability, and biocompatibility [14] [11]. |

| PBASE Linker | A common chemical linker (1-pyrenebutyric acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester) used for the stable attachment of biomolecules onto the surface of CNTs and graphene via π–π stacking [14]. |

| GelMA Hydrogel | A biocompatible hydrogel used to encapsulate and immobilize nanosensors (e.g., ssDNA-SWCNTs) for in vivo implantation and cellular studies [7]. |

| Nitrogen Dopant Precursors | Chemicals used to introduce nitrogen atoms into the lattice of Carbon and Graphene QDs, enhancing their electrocatalytic activity and creating more active sites [13]. |

The evolution of diagnostic technologies has marked a significant transition from conventional laboratory-based assays to advanced biosensing platforms, with transduction mechanisms forming the core of this innovation. Biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a transducer to detect and quantify a specific analyte [16]. The transducer's role is to convert the biological interaction into a measurable electrical, optical, or physical signal [17]. The accuracy and efficacy of modern diagnostics, particularly the emerging field of nanobiosensors, are fundamentally governed by the performance of these transduction systems. Within this context, electrochemical, optical, and piezoelectric transduction mechanisms have emerged as the three principal pillars, each with distinct operating principles, advantages, and limitations. This guide provides a structured comparison of these three core transduction mechanisms, framing their performance within the broader thesis of nanobiosensors versus traditional diagnostics accuracy research. It is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals by summarizing quantitative performance data and detailing essential experimental protocols.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Transduction Mechanisms

The selection of a transduction mechanism is critical for biosensor design, as it directly influences key analytical parameters such as sensitivity, detection limit, and response time. Table 1 provides a comparative summary of the core performance characteristics of electrochemical, optical, and piezoelectric biosensors, highlighting their suitability for different diagnostic applications.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Biosensor Transduction Mechanisms

| Performance Parameter | Electrochemical | Optical | Piezoelectric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Measures changes in electrical properties (current, potential, impedance) due to bio-recognition events [16] [18]. | Measures changes in light properties (wavelength, intensity, phase) upon analyte interaction [18] [17]. | Measures change in resonance frequency due to mass change on the sensor surface [19] [20]. |

| Typical Limit of Detection (LOD) | Very high sensitivity (e.g., attomolar (aM) for microRNA [21]). | Very high sensitivity (e.g., 84 aM for microRNA using nanobiosensors [21]). | Nanogram (ng) range per cm² (e.g., ~4.4 ng/cm² for a 10 MHz crystal) [20]. |

| Key Advantage(s) | High sensitivity, simplicity, low cost, portability, suitability for miniaturization and point-of-care (POC) devices [16] [18] [1]. | High sensitivity, capacity for multiplexing (detecting multiple analytes simultaneously), and ability for label-free detection [21] [18]. | Label-free detection, real-time monitoring of binding events, and simplicity of the measurement principle [19] [20]. |

| Primary Limitation(s) | Signal can be susceptible to interference from non-target molecules in complex matrices [18] [1]. | Instrumentation can be complex and costly; some formats may be susceptible to ambient light interference [1]. | Lack of sensitivity and specificity in liquid environments; performance is compromised in viscous solutions [19] [20]. |

| Representative Applications | Glucose monitoring, cardiac biomarker detection, environmental pollutants, foodborne pathogens [16] [18] [17]. | Infectious disease diagnostics (e.g., SARS-CoV-2), cancer biomarker detection, environmental monitoring [21] [17]. | Detection of viruses, bacteria, monitoring of cellular interactions, and enzyme activity studies [20] [18]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Transduction Mechanisms

A critical understanding for researchers is the methodology behind generating the data that informs performance tables like the one above. This section outlines generalized experimental protocols for each transduction mechanism.

Electrochemical Biosensor Protocol for Glucose Detection

This protocol is based on the classic amperometric glucose biosensor, which detects the current generated from the enzymatic production of hydrogen peroxide [16].

- Electrode Preparation: A three-electrode system (working, counter, and reference) is used. The working electrode (often gold or carbon) is cleaned and polished.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Glucose oxidase (GOx) is immobilized onto the working electrode surface. This can be achieved via methods like cross-linking with glutaraldehyde, entrapment within a polymer matrix (e.g., Nafion), or covalent bonding to a self-assembled monolayer.

- Sensor Assembly and Calibration: The electrode system is integrated into a electrochemical cell. A buffer solution is added, and a constant potential (e.g., +0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl) is applied. Standard glucose solutions of known concentration are introduced.

- Measurement and Transduction: As GOx catalyzes the oxidation of glucose, it produces hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). H₂O₂ is oxidized at the working electrode, generating an electrical current that is directly proportional to the glucose concentration [16].

- Data Analysis: The measured current is plotted against glucose concentration to create a calibration curve, which is used to determine the concentration of unknown samples.

Optical Biosensor Protocol for Antigen Detection using Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

This protocol details a label-free method for detecting antigens, such as a viral protein, using SPR [21].

- Sensor Chip Functionalization: A gold-coated SPR sensor chip is placed in the instrument. The surface is modified with a self-assembled monolayer to create a reactive interface.

- Ligand Immobilization: A specific antibody (ligand) is covalently immobilized onto the sensor chip surface using standard amine-coupling chemistry.

- Baseline Establishment: A running buffer is flowed over the sensor surface to establish a stable optical baseline, measured as a resonance angle.

- Association Phase: The sample containing the target antigen is injected and flowed over the chip. Binding of the antigen to the antibody causes a change in the refractive index at the surface, leading to a shift in the resonance angle, which is monitored in real-time.

- Dissociation Phase: The sample flow is replaced with buffer. The dissociation of the antigen-antibody complex is observed as a return of the signal towards the baseline.

- Regeneration: A mild acidic or basic solution is injected to break the antigen-antibody bonds, regenerating the surface for the next analysis cycle.

- Data Analysis: The sensorgram (a plot of resonance shift vs. time) is analyzed to determine the association and dissociation rate constants, from which the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) and analyte concentration are calculated.

Piezoelectric Biosensor Protocol for Bacterial Detection

This protocol utilizes a Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) to detect whole bacteria based on mass change [19] [20].

- Crystal Preparation: A quartz crystal with gold electrodes (e.g., AT-cut, 10 MHz) is cleaned. The gold surface is often modified with a chemical layer to facilitate bioreceptor attachment.

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: A specific antibody for the target bacteria is immobilized onto the crystal's electrode surface, typically through physical adsorption or covalent chemistry.

- Baseline Frequency Measurement: The crystal is incorporated into an oscillator circuit and its fundamental resonant frequency (f₀) is measured in air or a clean buffer solution to establish a stable baseline.

- Sample Exposure and Mass Transduction: The sample solution containing the target bacteria is introduced. Binding of the bacteria to the immobilized antibodies increases the mass on the crystal surface. According to the Sauerbrey equation, this mass increase (Δm) causes a proportional decrease in the resonant frequency (Δf) [20].

- Data Analysis: The frequency shift (Δf) is recorded. Using the Sauerbrey equation (Δm = -C · Δf, where C is a constant for the specific crystal), the mass of bound bacteria is quantified. A calibration curve with known bacterial concentrations is used for quantification.

System Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow and core signaling principles for each transduction mechanism, from analyte interaction to signal output.

Electrochemical Biosensor Workflow

Electrochemical Biosensor Signal Generation Pathway

Optical Biosensor Workflow

Optical Biosensor Signal Generation Pathway

Piezoelectric Biosensor Workflow

Piezoelectric Biosensor Signal Generation Pathway

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful development and implementation of biosensors rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. Table 2 details key components used across different transduction mechanisms, with their primary functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Core Function | Transduction System |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal amplification; enhance electron transfer in electrochemical sensors; plasmonic core in optical sensors [21] [16]. | Electrochemical, Optical |

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Model enzyme bioreceptor; catalyzes glucose oxidation to produce electroactive H₂O₂ [16]. | Electrochemical |

| Specific Antibodies | High-affinity biorecognition element for antigens, viruses, or bacteria [20] [16]. | Optical, Piezoelectric, Electrochemical |

| Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) Chip | Piezoelectric transducer; resonant frequency shifts with mass loading [19] [20]. | Piezoelectric |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Enhance electrode surface area and conductivity; improve sensitivity in electrochemical detection [16] [1]. | Electrochemical |

| SPR Sensor Chip (Gold Film) | Transducer surface for optical biosensors; supports plasmon wave generation sensitive to refractive index changes [21]. | Optical |

| Aptamers | Synthetic nucleic acid-based biorecognition elements; offer high stability and selectivity for targets [20] [16]. | Optical, Electrochemical |

| Fluorescent Dyes / Quantum Dots | Labels for generating optical signal in fluorescence-based biosensing assays [21] [1]. | Optical |

Electrochemical, optical, and piezoelectric transduction mechanisms each offer a unique set of capabilities that determine their suitability for specific diagnostic applications. Electrochemical systems excel in providing low-cost, portable, and highly sensitive platforms ideal for point-of-care testing, such as glucose monitoring. Optical biosensors offer superior capabilities for multiplexing and real-time, label-free kinetic analysis of biomolecular interactions, making them powerful tools for fundamental research and advanced clinical diagnostics. Piezoelectric biosensors provide a direct method for mass-sensitive detection, useful for monitoring cellular processes and pathogenic microbes. The ongoing integration of nanotechnology, through the use of nanomaterials like gold nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes, is consistently pushing the limits of all three transduction mechanisms, enabling the development of nanobiosensors with dramatically enhanced sensitivity and specificity. This progress is steadily bridging the performance gap between traditional diagnostic methods and modern biosensing platforms, paving the way for more accurate, rapid, and accessible diagnostics in research, clinical, and point-of-care settings.

The Evolution from Traditional Biosensors to Nano-Enhanced Platforms

The field of biosensing has undergone a revolutionary transformation, evolving from first-generation enzyme electrodes to sophisticated platforms enhanced by nanotechnology. This evolution has been driven by the persistent challenge of detecting disease biomarkers at ultra-low concentrations in complex biological fluids, a task where traditional methods often fall short. The integration of nanomaterials has fundamentally improved biosensor performance by leveraging unique properties such as high surface-to-volume ratios, quantum effects, and enhanced reactivity. This guide objectively compares the performance characteristics of traditional biosensors against nano-enhanced platforms, providing researchers and drug development professionals with experimental data and methodologies central to ongoing research on diagnostic accuracy.

Performance Comparison: Traditional vs. Nano-Enhanced Biosensors

The transition to nanotechnology has led to orders-of-magnitude improvements in key analytical metrics. The table below summarizes a direct performance comparison across critical parameters.

Table 1: Performance Comparison Between Traditional and Nano-Enhanced Biosensors

| Performance Parameter | Traditional Biosensors | Nano-Enhanced Biosensors | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | ~10–100 ng/mL (e.g., conventional ELISA) [22] | Femtogram to attomolar levels (e.g., 16.73 ng/mL for AFP; 0.64 fM for biomarkers) [23] [22] | SERS-based α-fetoprotein immunoassay; Aptamer-based SPR sensor [23] [22] |

| Sensitivity | Lower current/optical signal change per unit concentration | High sensitivity (e.g., 95.12 ± 2.54 µA mM⁻¹ cm⁻² for glucose) [23] | Nanostructured composite glucose electrode [23] |

| Selectivity | Good with specific bioreceptors | Enhanced specificity via functionalized nanomaterials (antibodies, aptamers on NPs) [22] [24] | Au-Ag nanostars for biomarker detection; Functionalized NPs for complex fluids [23] [24] |

| Response Time | Minutes to hours for steady-state signal | Rapid, real-time monitoring; Minutes faster using transient signal [25] [26] | Dynamic signal analysis with cantilever biosensors [26] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Limited, often single-analyte | High, simultaneous detection of multiple targets [22] | Nanobiosensor panels for biomarker profiling [22] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: SERS-Based Immunoassay for Protein Biomarkers

This protocol details a methodology for detecting α-fetoprotein (AFP) using a surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) platform with Au-Ag nanostars, demonstrating the practical application of nanomaterials for ultra-sensitive detection [23].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Au-Ag Nanostars: Plasmonic nanoparticles with sharp-tipped morphology for intense signal enhancement.

- Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA): A self-assembled monolayer for functionalizing the gold surface.

- EDC/NHS Crosslinkers: Activate carboxyl groups for covalent antibody immobilization.

- Monoclonal Anti-α-fetoprotein Antibodies (AFP-Ab): Biorecognition element for specific antigen capture.

Workflow:

- Nanostar Synthesis & Concentration: Synthesize Au-Ag nanostars and concentrate them via centrifugation (10-60 mins) [23].

- Substrate Functionalization: Incubate the nanostar platform with MPA to form a self-assembled monolayer. Then, activate the carboxyl groups using EDC and NHS chemistry [23].

- Antibody Immobilization: Covalently attach the monoclonal AFP-Ab to the activated platform [23].

- Sample Incubation & Washing: Expose the functionalized sensor to the sample solution containing the AFP antigen. Unbound molecules are removed by washing [23].

- Signal Acquisition & Analysis: Record the intrinsic SERS spectrum of the captured AFP. The limit of detection (LOD) is calculated to be 16.73 ng/mL [23].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow and the signal enhancement principle of the SERS-based nanostar platform.

Protocol 2: AI-Enhanced Dynamic Signal Analysis for microRNA

This protocol leverages machine learning to analyze the dynamic response of cantilever biosensors, significantly improving speed and accuracy while reducing false responses [25] [26].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- DNA-Functionalized Cantilever Biosensor: Piezoelectric sensor with a thiolated-DNA probe immobilized on a gold pad.

- microRNA let-7a Target: The analyte of interest (5′ UGAGGUAGUAGGUUGUAUAGUU 3′).

- Theory-Guided Feature Engineering: Extracts features from the binding kinetics (e.g., initial rate of signal change) as inputs for machine learning models [26].

Workflow:

- Data Acquisition: Monitor the resonant frequency (Δf) vs. time (t) as the miRNA binds to the cantilever in a continuous-flow format [26].

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize the dynamic signal to account for sensor-to-sensor variance [26].

- Data Augmentation: Address data sparsity and class imbalance using techniques like jittering and time warping [25] [26].

- Feature Engineering: Generate theory-based features informed by the kinetics of surface-based affinity biosensors [26].

- Model Training & Classification: Train a classifier (e.g., Support Vector Machine) to categorize the biosensor response into target concentration bins, enabling quantification of false-positive and false-negative probabilities [26].

The logical workflow for this AI-enhanced methodology is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The development and operation of high-performance nanobiosensors rely on a specific set of materials and tools. This table details key research reagent solutions and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Nanobiosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) & Nanostars | Plasmonic enhancement, high surface area for bioreceptor immobilization, improved conductivity [23] [22] [27] | SERS-based immunoassays; Electrode modification [23] |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Enhance electron transfer, increase effective surface area, act as transducer element [22] [24] [27] | Electrochemical sensor electrodes for neurotransmitters [22] |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Fluorescent probes with size-tunable emission and high photostability [3] [27] | Optical biosensing and multiplexed detection [27] |

| Aptamers | Synthetic nucleic acid bioreceptors with high specificity and stability [22] | Target recognition for electrochemical and optical sensors [22] |

| EDC/NHS Chemistry | Crosslinking system for covalent immobilization of biomolecules on sensor surfaces [23] | Antibody attachment to functionalized nanomaterials [23] |

| Microfluidic Chips | Provide lab-on-a-chip platform for precise fluid manipulation, high throughput, and minimal reagent use [28] | Isolation and analysis of extracellular vesicles (EVs) [28] |

The evolution from traditional to nano-enhanced biosensors represents a quantitative and qualitative leap in diagnostic capability. Experimental data confirms that nanomaterials directly enhance performance by improving sensitivity, lowering detection limits, and enabling faster, multiplexed analyses. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence with dynamic signal analysis introduces a powerful new dimension for improving accuracy and reducing time delay. For researchers and drug development professionals, these advanced platforms offer powerful tools for fundamental research and the development of next-generation clinical diagnostics, particularly for early disease detection where biomarker concentrations are minimal. The continued convergence of nanotechnology, advanced materials, and data science promises to further redefine the limits of biosensing.

Methodologies and Cutting-Edge Applications in Disease Detection

Liquid biopsy has emerged as a compelling minimally invasive alternative to traditional tissue biopsy for cancer diagnosis and monitoring. This approach involves screening for disease-related markers from blood or other biofluids, promising early diagnosis, timely prognostication, and effective treatment monitoring [29]. Unlike traditional tissue biopsies, which provide information from a specific lesion location and can be risky and painful, liquid biopsy captures biomarkers shed into the bloodstream, offering a more comprehensive view of tumor heterogeneity [29]. The primary biomarkers detected through liquid biopsy include circulating tumor cells (CTCs), circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), and tumor-derived exosomes containing microRNAs (miRNAs) [29]. However, these biomarkers present significant detection challenges due to their extraordinarily low abundance amidst normal cellular components in biofluids, necessitating ultra-sensitive and accurate detection methods [29]. This review comprehensively compares these three biomarker classes within the context of nanobiosensors versus traditional diagnostic approaches, providing experimental data and methodological insights for research professionals.

Biomarker Characteristics and Clinical Significance

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Cancer Biomarkers

| Biomarker | Origin & Composition | Concentration in Cancer | Primary Clinical Applications | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTCs | Intact cancer cells shed from primary or metastatic tumors | Extremely rare (few cells among billions of blood cells) [30] | Assessing tumor heterogeneity, guiding immunotherapy, monitoring minimal residual disease [30] | Specialized isolation methods needed; extreme rarity [29] [30] |

| ctDNA | Fragmented tumor-derived DNA (∼150-350 bp) released into circulation [31] | Short fragments (median: 175 bp in pancreatic cancer) [31] | Early cancer detection, therapy monitoring, tracking resistance mutations [31] | Low fractional abundance; requires ultra-sensitive detection [29] |

| miRNAs | Small non-coding RNAs (~22 nucleotides) packaged in exosomes or protein complexes [32] | Varies by specific miRNA; often dysregulated in cancer [33] | Diagnostic/prognostic biomarkers, therapeutic targets [32] [33] | Panel approach needed for sufficient accuracy [33] |

Traditional Detection Methods Versus Nanobiosensor Approaches

Established Conventional Techniques

Traditional methods for biomarker detection have formed the foundation of liquid biopsy but present significant limitations for clinical implementation:

CTC Detection: Traditional approaches include immunomagnetic separation (CellSearch system) and size-based filtration methods, often followed by immunohistochemical analysis or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) [30]. These methods face challenges in processing large blood volumes sufficient for rare cell capture and often lack standardization for single-cell molecular analyses [30].

ctDNA Analysis: Next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms serve as the cornerstone for ctDNA mutation profiling, with digital PCR (dPCR) providing ultra-sensitive quantification of specific mutations [31]. These methods exploit fragmentomic patterns, with pancreatic cancer patients showing significantly shorter cfDNA fragments (median: 175 bp) compared to controls (182-186 bp) [31]. While established, these technologies can be costly and require sophisticated bioinformatics infrastructure.

miRNA Profiling: Conventional methods include next-generation sequencing, microarray analysis, Northern blotting, and reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) [32]. These techniques have been essential for miRNA biomarker discovery but often lack the sensitivity for direct clinical application without pre-amplification steps and struggle with multiplexing capabilities [32].

Nanobiosensor Platforms and Performance Metrics

Nanobiosensors represent a transformative approach to biomarker detection, leveraging the unique properties of nanomaterials to overcome limitations of conventional methods:

Enhanced Sensitivity and Specificity: Nanobiosensors incorporate engineered nanomaterials such as gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), quantum dots (QDs), carbon nanotubes, and graphene as functional components to improve signal generation and amplification [21]. These materials provide substantially increased surface-area-to-volume ratios, enhancing biorecognition element density and improving detection limits [29] [21].

CTC Capture Technologies: Emerging rare cell capture technologies employing nanostructured substrates functionalized with capture antibodies can process larger blood volumes and enable advanced single-cell analyses [30]. These platforms demonstrate superior capture efficiency and purity compared to conventional methods, with the additional capability of releasing captured cells alive for downstream molecular characterization [30].

ctDNA Detection Innovations: Nanoplasmonic sensors and electrochemical nanosensors have demonstrated capability in detecting cancer-specific fragmentation patterns and methylation signatures in ctDNA [29]. These platforms can distinguish pancreatic cancer patients from healthy controls with high accuracy based on fragmentomic profiles without requiring sequencing [31].

miRNA Sensing Platforms: Nanomaterial-based fluorimetric and electrochemical techniques enable highly sensitive, efficient, and selective detection of miRNAs, addressing the limitations of Northern blotting and RT-qPCR [32]. For colorectal cancer detection, multi-miRNA panels in plasma samples demonstrate pooled sensitivity of 0.85 and specificity of 0.84, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.90 across 29 studies [33].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Detection Platforms

| Detection Platform | Limit of Detection | Analysis Time | Multiplexing Capacity | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional CTC Capture | 1-10 CTCs/mL [30] | 3-6 hours | Low | FDA-approved systems available |

| Nano-enhanced CTC Capture | Improved rare cell detection [30] | 1-3 hours | Moderate | Viable cell retrieval; integrated analysis |

| NGS ctDNA Profiling | VAF: 0.1-1% [31] | 2-5 days | High | Comprehensive mutation profiling |

| Nanobiosensor ctDNA | Comparable to NGS [29] | Minutes-hours | Moderate | Point-of-care potential; lower cost |

| RT-qPCR miRNA | ~pM concentrations [32] | 2-4 hours | Low-medium | Gold standard; quantitative |

| Nanosensor miRNA | aM-fM concentrations [21] | <1 hour | High | Superior sensitivity; minimal sample prep |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

CTC Enrichment and Molecular Characterization Protocol

Advanced CTC analysis workflows integrate nanomaterial-based capture with single-cell omics technologies:

Blood Collection and Processing: Collect 5-10 mL peripheral blood in EDTA or CellSave tubes. Process within 4-24 hours of collection [30].

Nanomaterial-Based CTC Enrichment:

- Incubate blood samples with immunomagnetic nanoparticles conjugated to epithelial (EpCAM) or cancer-specific antibodies

- Apply to microfluidic devices with nanostructured surfaces for enhanced contact and capture efficiency

- Use negative depletion to remove hematopoietic cells using CD45-conjugated nanoparticles

Downstream Molecular Analysis:

- Isolate single CTCs using micromanipulation or microfluidic sorting

- Perform whole genome amplification for copy number alteration analysis

- Conduct RNA sequencing for transcriptional profiling

- Implement protein biomarker characterization using immunocytochemistry

This integrated approach enables the assessment of tumor heterogeneity and identification of heterogeneous drug resistance mechanisms [30].

cfDNA-Based Multi-Feature Analysis for Pancreatic Cancer Detection

A comprehensive cfDNA analysis protocol leveraging multiple molecular features demonstrates superior diagnostic performance:

Sample Preparation and Sequencing:

- Collect plasma from 5 mL blood following double centrifugation protocol

- Extract cfDNA using silica-membrane or magnetic bead-based kits

- Prepare sequencing libraries with 50-100 ng cfDNA input

- Perform low-pass whole-genome sequencing (∼0.5-1× coverage) on DNBSEQ or similar platforms [31]

Multi-Dimensional Feature Extraction:

- Fragmentomics Analysis: Calculate fragment size distribution, end motif preferences, and nucleosome footprinting patterns [31]

- Copy Number Alteration (CNA) Profiling: Identify chromosomal gains and losses using circular binary segmentation algorithm

- Nucleosome Footprint (NF) Analysis: Map protected regions indicative of nucleosome positioning

Predictive Model Construction:

- Apply Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression to select most predictive features

- Construct a weighted diagnostic model (PCM score) integrating fragment, motif, NF, and CNA signatures

- Validate model performance in independent cohorts (AUC: 0.979-0.992 across validation sets) [31]

This multi-feature approach significantly outperforms single-analyte models, distinguishing early-stage pancreatic cancer from healthy controls with AUC of 0.994 [31].

Multi-miRNA Panel Validation for Colorectal Cancer Detection

A systematic framework for developing and validating miRNA panels as diagnostic tools:

miRNA Extraction and Quality Control:

- Isolate miRNAs from 200-500 μL plasma/serum using phenol-chloroform or column-based methods

- Include synthetic spike-in controls (e.g., cel-miR-39) for normalization

- Assess RNA quality using Agilent Bioanalyzer small RNA assay

Profiling and Panel Selection:

- Perform initial discovery phase using miRNA microarrays or NGS on training cohort

- Identify differentially expressed miRNAs with statistical significance (p<0.05, FDR correction)

- Construct multi-miRNA panels using combinatorial optimization or machine learning approaches

- Three-miRNA panels typically demonstrate optimal diagnostic trade-offs [33]

Analytical Validation:

- Validate selected panels using RT-qPCR with stem-loop primers in independent cohorts

- Calculate diagnostic metrics (sensitivity, specificity, AUC) using receiver operating characteristic analysis

- Perform mechanistic validation by mapping recurrent miRNAs to canonical cancer pathways (e.g., PI3K/AKT, Wnt/β-catenin) [33]

This systematic approach has established that multi-miRNA panels achieve pooled sensitivity of 0.85 and specificity of 0.84 for colorectal cancer detection across 29 studies comprising 5,497 participants [33].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Integrated Workflow for Multi-Biomarker Liquid Biopsy Analysis

Diagram 2: miRNA Biomarkers in Oncogenic Pathways and Detection Platforms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Liquid Biopsy Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunomagnetic Nanoparticles | CTC enrichment via epitope-specific capture (e.g., EpCAM, HER2) | Isolation of rare CTCs from whole blood [30] | Enable viable cell release for downstream culture/analysis |

| Silica-coated Magnetic Beads | Nucleic acid binding and purification | cfDNA and miRNA extraction from plasma/serum [31] | Higher recovery rates vs. traditional phenol-chloroform |

| Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) Probes | Enhanced hybridization affinity for miRNA detection | Northern blotting, in situ hybridization [32] | Increased melting temperature and specificity |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Fluorescent labeling with narrow emission spectra | Multiplexed biomarker detection, cellular imaging [29] [21] | Superior photostability vs. organic dyes |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal amplification in colorimetric/electrochemical sensors | Lateral flow assays, SERS-based detection [21] [34] | Tunable optical properties based on size/shape |

| Plasmonic Nanostructures | Enhanced electromagnetic fields for single-molecule detection | SERS-based biomarker quantification [21] | Enable detection at attomolar concentrations |

| DNA Nanoballs (DNB) | High-density sequencing templates | Low-pass whole genome sequencing of cfDNA [31] [35] | Reduce sequencing errors and costs |

The integration of nanobiosensors in liquid biopsy applications represents a paradigm shift in cancer diagnostics, offering unprecedented sensitivity and specificity for detecting CTCs, ctDNA, and miRNAs. While traditional methods like NGS and RT-qPCR remain essential for biomarker discovery and validation, nanomaterial-based platforms demonstrate clear advantages in point-of-care potential, cost-effectiveness, and processing time. The future of cancer diagnostics lies in multi-analyte approaches that combine the strengths of different biomarker classes, such as integrating cfDNA fragmentomics with miRNA panels and CTC protein markers. Emerging technologies including microfluidic-nanobiosensor integration, artificial intelligence-assisted analysis, and single-molecule detection platforms will further enhance diagnostic precision [21]. For research and drug development professionals, understanding the complementary nature of these biomarkers and their optimal detection platforms is crucial for advancing precision oncology and developing novel therapeutic strategies. As standardization improves and large-scale validation studies accumulate, these technologies are poised to transform cancer screening, monitoring, and personalized treatment selection.

The management of neurodegenerative diseases, particularly synucleinopathies like Parkinson’s disease (PD), is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving from reliance on clinical symptoms to objective biological measures. This shift is centered on the detection of pathological biomarkers, with alpha-synuclein (α-syn) taking a primary role. The aggregation of α-synuclein protein in neurons is a defining pathological hallmark of a spectrum of disorders, including Parkinson's disease (PD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and multiple system atrophy (MSA) [36]. Currently, the gold-standard for diagnosis remains a detailed clinical evaluation, which can be prone to error, especially in early disease stages or atypical presentations [36]. The development of tools for direct in vivo detection of α-synuclein pathology represents a critical unmet need in both research and clinical care [36].

This article provides a comparative analysis of emerging diagnostic technologies, framing them within the broader thesis of nanobiosensors versus traditional diagnostics accuracy research. We objectively compare the performance of innovative sensing platforms against established methods, providing supporting experimental data and detailed protocols to illustrate the rapid advancements in this field. The ability to accurately detect and measure α-synuclein and related biomarkers is crucial not only for early and accurate diagnosis but also for monitoring disease progression, stratifying patients for clinical trials, and evaluating the efficacy of novel disease-modifying therapies [36] [37].

Performance Comparison: Traditional Assays vs. Next-Generation Platforms

The evolution of α-synuclein detection technologies has significantly enhanced sensitivity, allowing for earlier disease identification and the use of more accessible biofluids like blood plasma. The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of various diagnostic platforms.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of α-Synuclein Detection Platforms

| Technology / Platform | Detection Mechanism | Sample Type | Detection Limit | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional ELISA [22] [38] | Enzyme-linked colorimetric assay | CSF, Plasma | ~10-100 ng/mL (general for proteins) | Well-established, standardized |

| Seed Amplification Assays (SAA) [36] [39] | Amplification of misfolded protein seeds | CSF, Skin biopsy | Qualitative (Presence/Absence) | High correlation with clinical diagnosis, detects pathological forms |

| SIMOA [38] | Digital immunoassay (fluorescence) | CSF, Plasma | Femtomolar range | Ultra-high sensitivity, quantifies low concentrations in blood |

| Electrochemical Nanobiosensor [40] | Impedance spectroscopy (Electrochemical) | Plasma | 0.08 pg/mL | Extreme sensitivity, low-cost, point-of-care potential |

| PET Tracers [37] | Molecular imaging | In vivo (Brain) | N/A (Spatial distribution) | Direct in vivo visualization, regional distribution |

The data reveals a clear trend: nanobiosensor technology achieves detection limits that are orders of magnitude lower than traditional methods like ELISA. For instance, a specific electrochemical nanobiosensor demonstrated a limit of detection of 0.08 pg/mL in human plasma, a sensitivity level that reliably allows for discrimination between healthy individuals and PD patients [40]. This is crucial because α-synuclein concentrations in blood plasma are typically very low, reported as 0.157 ± 0.285 pg·mL⁻¹ for healthy controls [40]. Furthermore, while Seed Amplification Assays are groundbreaking for detecting the pathological form of α-synuclein, they are primarily qualitative [39]. In contrast, nanobiosensors and SIMOA provide quantitative data, which is more valuable for tracking changes in biomarker levels over time.

Experimental Protocols for Key Technologies

Protocol: α-Synuclein Electrochemical Nanobiosensor

This protocol details the fabrication and operation of a highly sensitive hierarchical nanowire-based electrode for detecting α-synuclein in plasma, as presented in the search results [40].

- 1. Electrode Fabrication: Begin with a cleaned PET-ITO substrate. Synthesize ZnO nanowires arranged as nanostars (NS) using a chemical bath deposition (CBD) method. Decorate the ZnO NSs with gold nanoparticles (Au NPs) via electrodeposition from a HAuCl₄ solution. Grow a layer of poly-glutamic acid through electro-polymerization onto the Au NP/ZnO NS structure.

- 2. Biorecognition Immobilization: Functionalize the sensor surface by covalently attaching anti-α-synuclein antibodies to the poly-glutamic acid layer. This is typically achieved using carbodiimide crosslinker chemistry (e.g., EDC/NHS). Block non-specific binding sites with Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA).

- 3. Sample Incubation & Measurement: Incubate the functionalized biosensor with a prepared sample of human plasma. After a washing step to remove unbound material, the electrochemical measurement is performed using a solution of Fe(II)(CN)₆⁴⁻/Fe(III)(CN)₆³⁻ as a redox probe. The binding of α-synuclein to the immobilized antibody increases the electrical impedance at the electrode surface.

- 4. Data Analysis: The change in charge transfer resistance (Rₑₜ) is measured via Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS). This change is correlated with the concentration of α-synuclein in the sample using a pre-established calibration curve, which is linear in the range of 0.5 to 10 pg·mL⁻¹ [40].

Protocol: Seed Amplification Assay (SAA) for Misfolded α-Synuclein

This protocol outlines the general principles for detecting pathological α-synuclein aggregates, a method highlighted in recent research updates [36] [39].

- 1. Sample Preparation: Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is collected via lumbar puncture and prepared with a buffer to maintain protein stability.

- 2. Seeding Reaction: The CSF sample is mixed with a solution containing recombinant α-synuclein monomer substrate and an energy source (e.g., buffer salts). The mixture is subjected to cycles of agitation and incubation in a thermostated plate reader. If pathological α-synuclein "seeds" are present in the CSF sample, they will template the conversion and aggregation of the monomeric substrate into amyloid fibrils.

- 3. Signal Detection: The formation of aggregates is monitored in real-time using a fluorescent dye, such as Thioflavin T (ThT), which intercalates into amyloid fibrils and exhibits enhanced fluorescence. Samples are classified as positive or negative based on the fluorescence reaching a predetermined threshold within the assay time.

- 4. Data Interpretation: The kinetic parameters of the aggregation (e.g., lag time, maximum fluorescence) can provide information on the concentration and seeding activity of the pathological α-synuclein in the original sample. It is noted that while SAA strongly correlates with symptoms, it does not reliably predict disease progression on its own [39].

Diagnostic Pathways and Technology Integration

The following diagram visualizes the integrated diagnostic and research workflow for synucleinopathies, incorporating both established and emerging technologies.

Diagnostic and Research Workflow for Synucleinopathies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful research and development in this field rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table catalogues essential components for building advanced diagnostic platforms for α-synuclein detection.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for α-Synuclein Biomarker Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-α-Synuclein Antibodies | Biorecognition element for immunoassays; binds specifically to α-synuclein protein. | Clone 1D22 Rabbit Monoclonal antibody used in electrochemical biosensor functionalization [40]. |

| Functional Nanomaterials | Enhance sensor signal, increase surface area, and improve electron transfer. | Gold nanoparticles (Au NPs), Zinc Oxide Nanostars (ZnO NSs), exfoliated graphene oxide (EGO), carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [22] [40] [41]. |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Ultra-sensitive nucleic acid detection; can be adapted for protein biomarkers via aptamer sequences. | Cas proteins with guide RNA (gRNA) used in fluorescence-based biosensors for attomolar-level sensitivity [38]. |

| Recombinant α-Synuclein | Essential substrate for Seed Amplification Assays (SAA); used as a standard for calibration curves. | Used in SAA protocols to amplify pathological seeds from patient CSF [36]. |

| PET Tracer Candidates | Allow for direct in vivo imaging of α-synuclein aggregates in the brain. | Novel tracers from Merck and MGH presented at AD/PD 2025, showing proof-of-concept in humans [37]. |