Machine Learning Optimized Carbon Nanolattices: Designing the Next Generation of Biomaterials

This article explores the groundbreaking integration of machine learning (ML) with the design and optimization of carbon nanolattices, a class of nano-architected materials.

Machine Learning Optimized Carbon Nanolattices: Designing the Next Generation of Biomaterials

Abstract

This article explores the groundbreaking integration of machine learning (ML) with the design and optimization of carbon nanolattices, a class of nano-architected materials. We detail how multi-objective Bayesian optimization is used to create structures with unprecedented mechanical properties, such as the strength of carbon steel at the density of Styrofoam. For researchers and drug development professionals, we examine the methodological advances in ML-driven design, address key optimization challenges, and validate performance through comparative analysis. The discussion extends to the transformative potential of these optimized nanolattices in biomedical applications, including advanced drug delivery systems, lightweight implantable devices, and diagnostic tools.

The New Paradigm of Nano-Architected Materials

Defining Carbon Nanolattices and Their Structural Principles

Definition and Basic Principles

Carbon Nanolattices are a class of nano-architected materials composed of tiny building blocks or repeating units measuring a few hundred nanometers in size—it would take more than 100 of them patterned in a row to reach the thickness of a human hair [1] [2]. These building blocks, composed of carbon, are arranged in complex three-dimensional structures called nanolattices [1] [2]. They achieve exceptional mechanical properties through a combination of structurally efficient geometries, high-performance constituent materials, and nanoscale size effects [3].

The fundamental structural principle involves treating "material" as a geometry problem, asking which internal architecture at the nanoscale distributes stress perfectly and wastes nothing [4]. Unlike traditional materials that are carved down from larger blocks, nano-architected materials are built up using precise geometries that leverage the "smaller is stronger" effect—as features shrink to nanoscale dimensions, flaws diminish, interfaces strengthen, and performance climbs [4] [1] [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What causes premature failure in traditional nanolattice designs, and how does machine learning address this?

- Problem: Traditional nano-architected designs with conventional topologies (uniform beam elements with sharp intersections and corners) exhibit poor stress distributions and induce premature nodal failure, which limits their overall potential [1] [3]. Stress concentrations at these sharp corners lead to early local failure and breakage [1] [2].

- ML Solution: Machine learning, specifically the multi-objective Bayesian optimization algorithm, designs non-intuitive geometries that redistribute material to minimize stress concentrations [4] [3]. The optimized designs often thicken near nodes, slenderize in mid-spans, and curve in ways that neutralize stress concentrations, resulting in a lattice that shares the load everywhere rather than cracking at the joints [4] [5]. This approach has led to improvements in strength by up to 118% and Young's modulus by up to 68% compared to standard lattices of equivalent density [3] [6].

FAQ 2: Why is the reduction of strut diameter to ~300 nm critical for enhanced performance?

- Problem: Larger strut diameters (e.g., 600 nm) in pyrolytic carbon do not fully exploit nanoscale size effects, resulting in lower specific strength and stiffness [3].

- Solution & Principle: Reducing strut diameters to approximately 300 nm triggers beneficial size effects [4] [3] [6]. At this scale, there are fewer defects, and the pyrolysis process creates a unique radial gradient atomic architecture with a stiffer, cleaner outer shell rich in sp² aromatic carbon (up to 94%) and low oxygen impurities [4] [3] [6]. This gradient structure significantly enhances mechanical properties, with experimental results showing as much as 75% enhancement in stiffness and 79% enhancement in strength compared to larger struts [3]. However, reducing strut diameters below 300 nm often leads to loss of geometric fidelity due to voxel print resolution and warping during pyrolysis [3].

FAQ 3: We are experiencing warping and defects when scaling nanolattices to macroscopic dimensions. How can this be mitigated?

- Problem: Scaling nanolattices from microscopic to macroscopic dimensions (millimeter-scale and beyond) introduces challenges such as pyrolysis-induced warping and defects when stitching together multiple fields of view during printing [4].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Process Control during Pyrolysis: Meticulously control the heating and cooling rates during the pyrolysis process to minimize thermal stresses that cause warping, especially for larger parts [4].

- Advanced Printing Techniques: Utilize multi-focus two-photon polymerization (2PP) systems instead of single-focus systems. This technology can print millions of unit cells in parallel, significantly increasing throughput and reducing stitching defects [4] [3] [6]. One study successfully fabricated a macroscopic nanolattice consisting of 18.75 million lattice cells using this approach [3] [6].

- Hybrid Manufacturing Approach: For current limitations, employ a hybrid approach: print high-value, complex lattice cores and then overmold them with a conventional material to create a composite structure. This bridges the gap until full-scale direct printing matures [4].

FAQ 4: Our AI-designed lattice geometries appear non-intuitive and complex. How can we validate their performance prior to fabrication?

- Problem: Machine learning-generated lattice geometries are often non-intuitive, featuring curves and tapers that a human designer might not conceive, raising questions about their validity [4] [3].

- Validation Protocol:

- Finite Element Analysis (FEA): Perform high-fidelity FEA simulations on the AI-proposed designs to analyze stress distribution under compressive and shear loads. The goal is to confirm a uniform stress distribution and the absence of high-stress concentrations at the nodes [3] [5].

- Benchmarking: Compare the simulated mechanical properties (Young's modulus, shear modulus, and predicted strength) of the new design against simulated data from traditional lattice geometries (e.g., standard CFCC or CBCC lattices) at the same density [3].

- Iterative Refinement: Use a closed-loop system where the initial FEA data trains the Bayesian optimizer. The algorithm then proposes improved designs, which are again validated through simulation before being selected for fabrication (

Simulate → Print → Pyrolyze → Test → Refit the model) [4].

Key Experimental Data

Table 1: Mechanical Performance Comparison: Traditional vs. AI-Optimized Nanolattices

| Property | Traditional Nanolattices | AI-Optimized Nanolattices | Improvement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Strength | Lower, varies with design | 2.03 MPa·m³/kg (record value) | >1 order of magnitude higher than equivalent low-density materials | [3] [6] |

| Compressive Strength | Lower, limited by nodal failure | 180 - 360 MPa (comparable to carbon steel) | Up to 118% increase | [4] [3] [6] |

| Young's Modulus | Lower, limited by stress concentrations | 2.0 - 3.5 GPa (comparable to soft woods) | Up to 68% increase | [3] [6] [5] |

| Density | ~125-215 kg/m³ (Foam-like) | ~125-215 kg/m³ (Foam-like) | No significant change (optimized at equivalent density) | [4] [3] |

Table 2: Key Material and Process Parameters for Optimized Carbon Nanolattices

| Parameter | Optimal Value / Description | Impact / Rationale | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strut Diameter | ~300 nm | Maximizes nanoscale "smaller is stronger" effect; promotes sp² carbon formation. | [4] [3] [6] |

| Carbon Bonding | ~94% sp² aromatic carbon (at 300 nm struts) | Creates a stiffer, stronger atomic structure; approaches diamond-like specific strength. | [3] [6] |

| Pyrolysis Temperature | 900 °C | Converts polymer precursor to glassy, sp²-rich carbon; shrinks structure to 20% of original size. | [3] [6] |

| ML Algorithm | Multi-objective Bayesian Optimization | Efficiently explores design space with high-quality, small datasets (~400 data points). | [1] [3] [7] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: AI-Driven Design and Optimization Workflow

This protocol describes the end-to-end process for designing and manufacturing AI-optimized carbon nanolattices.

AI-Driven Design and Manufacturing Workflow

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Problem Definition: Define the multi-objective optimization goals, typically to maximize effective Young's modulus (

E) and shear modulus (μ) while minimizing relative density (ρ) [3]. - Algorithm Initialization: The multi-objective Bayesian optimization algorithm begins by randomly generating an initial set of 400 lattice beam geometries within the design space [1] [3].

- Finite Element Analysis (FEA): Each randomly generated geometry is evaluated using FEA to calculate its relative density, effective Young's modulus, and effective shear modulus. This creates a high-quality initial dataset [3].

- Iterative Optimization: The Bayesian optimization algorithm uses the FEA data to build a predictive model. It then iteratively explores the design space, focusing on regions likely to contain optimal trade-offs between the objectives (the Pareto front). This process continues for about 100 iterations [3].

- Design Selection: From the optimized results, select generative designs that approach the Pareto-optimal surface, often those that maximize a combined metric like

[E/ρ · μ/ρ]^0.5to account for multi-modal loading [3]. - 3D Model Generation: Convert the optimized 2D beam profile into a 3D strut by revolving the Bézier curve, then symmetrically apply these struts to the nodes of a chosen lattice topology (e.g., Cubic-Face Centered Cubic - CFCC) to create a full 3D unit cell [3].

- Pattern Replication: Pattern the unit cell into a larger lattice (e.g., 5x5x5) for fabrication and testing [3].

Protocol 2: Fabrication and Pyrolysis for Carbon Nanolattices

This protocol details the manufacturing process following the digital design phase.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) Printing:

- Use a high-resolution 3D printer (e.g., Nanoscribe Photonic Professional GT2) [8].

- "Write" the designed nanolattice directly into a photosensitive resin using a laser, creating voxels a few hundred nanometers wide [4]. This process is called Two-Photon Polymerization and enables 3D printing at the micro and nano scale [1] [2].

- For scalability, employ a multi-focus 2PP system that can print millions of unit cells in parallel, significantly increasing throughput compared to single-focus methods [4] [3] [6].

- Pyrolysis Conversion:

- Place the 3D-printed polymer structure in a high-temperature furnace under an inert atmosphere.

- Heat to 900°C [3] [6].

- This process, called pyrolysis, converts the crosslinked polymer into a glassy, sp²-rich carbon by burning away other substances [4] [9].

- The structure will shrink to approximately 20% of its original printed size, locking in the final, dense carbon architecture [4] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for Carbon Nanolattice Research

| Item Name | Function / Role in the Workflow | Key Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) Lithography System | High-resolution additive manufacturing to create the 3D polymer nanostructure. | e.g., Nanoscribe Photonic Professional GT2; enables printing with voxels of a few hundred nanometers [8]. Multi-focus systems are key for scalability [4]. |

| Photosensitive Resin | The raw material that is solidified by the laser during the 2PP process to form the polymer scaffold. | A proprietary, crosslinkable polymer resin designed for high-resolution lithography and subsequent pyrolysis [3]. |

| Pyrolysis Furnace | High-temperature oven used to convert the 3D-printed polymer structure into pure carbon. | Must be capable of reaching and maintaining 900°C under a controlled (inert) atmosphere to prevent oxidation [3] [6]. |

| Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization Software | The machine learning algorithm that generates the optimal lattice geometries. | Efficiently explores complex design spaces with limited, high-quality data (~400 points) [1] [3]. |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) Software | Simulates the mechanical response (stress, strain) of proposed lattice designs under load. | Used to generate the high-quality training data for the ML algorithm and to validate designs before fabrication [3]. |

| Sputter Coater | Applies a thin, conductive metal layer (e.g., gold, platinum) to the polymer lattice before electron microscopy. | Necessary for high-quality imaging with a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), as the polymer and carbon are not inherently conductive. |

| Nanomechanical Test System (e.g., Nanoindenter) | Measures the mechanical properties (Young's modulus, strength) of the fabricated nanolattices. | Must be capable of performing uniaxial compression tests on micro- to nano-scale samples [3]. |

Technical Support Center: FAQs and Troubleshooting

This section addresses frequently asked questions and common experimental challenges encountered when researching nanoscale materials and machine learning-optimized nanostructures.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the "smaller is stronger" effect, and what are its limits? The "smaller is stronger" effect describes the phenomenon where the mechanical strength of a material increases as its physical dimensions are reduced to the nanoscale. This is often due to the fact that in small, defect-free volumes, higher stresses are required to nucleate dislocations to mediate plastic deformation [10]. However, this relationship is not monotonic. For nanoparticles, a complex, non-monotonic dependence of strength on size has been observed, with a peak strength typically occurring at sizes around 30–60 nm, followed by weakening in single-digit nanometer sizes where diffusive deformation dominates [11].

Q2: My carbon nanolattices are failing at the nodes. How can I improve their strength? Traditional nanolattice designs with uniform struts and sharp corners are prone to stress concentrations at the nodes and junctions, leading to premature failure [12] [3]. To mitigate this, utilize a multi-objective Bayesian optimization (MBO) algorithm to generatively design lattice geometries. This machine learning approach can create non-intuitive, curved beam elements that redistribute material toward the nodes, thinning the mid-beam regions to achieve a more homogeneous stress distribution and eliminate nodal stress concentrations [3].

Q3: What are the best practices for fabricating high-strength carbon nanolattices? A robust protocol involves two key steps:

- Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP): Use this high-resolution 3D printing technology to create a polymeric nanostructure from a photosensitive resin. This technique enables patterning at the nanoscale, producing features with diameters as small as 200-300 nm [3] [13].

- Pyrolysis: Convert the polymeric structure into glassy carbon by heating it under vacuum at temperatures around 900 °C. This process transforms the polymer into a high-performance, aromatic carbon structure and causes isotropic shrinkage of approximately 80%, resulting in the final, ultra-strong nanolattice [3] [13].

Q4: Why are my nanotube solutions forming aggregates, and what is their shelf life? Aqueous nanotube solutions stabilized with surfactants have a limited shelf life. The recommended "Best-If-Used-By" (BIUB) date is typically 6 months after production. Beyond this, nanotubes and surfactants can begin to irreversibly aggregate, forming darkened spots and white strands. For best results, use the solutions within 3 months of purchase and store them at room temperature without direct sunlight [14].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low specific strength in nanolattices | Suboptimal geometry causing stress concentrations; Strut diameter too large [3]. | Implement Bayesian optimization for generative design. Reduce strut diameter to 300 nm or less to enhance nanoscale confinement effects [3]. |

| Irreversible aggregation in nanotube solutions | Solution is past its shelf-life; surfactant has degraded [14]. | Check the BIUB code on the solution container. For new orders, plan experiments to use the solution within 3 months of receipt [14]. |

| Weakening in single-digit nm nanoparticles | Shift in deformation mechanism from dislocation-mediated to diffusive, "liquid-like" deformation [11]. | This is a fundamental size effect. Account for this regime in experimental design; strength may be described by zero-creep analysis rather than traditional models [11]. |

| Geometric fidelity loss during pyrolysis | Strut diameters are below the resolution limit of the fabrication process [3]. | Ensure printed polymer strut diameters are sufficiently large to account for ~80% shrinkage during pyrolysis. Struts below ~300 nm pre-pyrolysis may not retain shape [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Machine Learning-Optimized Fabrication of Carbon Nanolattices

This protocol details the synthesis of high-strength carbon nanolattices using a generative machine-learning approach [12] [3].

Generative Design via Bayesian Optimization:

- Objective: Define the optimization goals: maximize effective Young's modulus ((E)), maximize effective shear modulus ((\mu)), and minimize relative density ((\bar{\rho})) [3].

- Algorithm: Employ a Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MBO) algorithm.

- Process:

- Generate an initial dataset of 400 random lattice geometries.

- Use Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to evaluate (E), (\mu), and (\bar{\rho}) for each geometry.

- The algorithm iteratively expands a 3D hypervolume to identify the Pareto optimum surface, predicting new geometries that balance the three objectives.

- Output: An optimized unit cell design, typically featuring curved beam elements with material thinned at the mid-beam and thickened near the nodes.

Nanoscale Additive Manufacturing:

- Technique: Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP).

- Material: Use a photocurable acrylic polymer resin.

- Process: The optimized 3D model is printed using a 2PP system to create a polymeric nanolattice. The printed structure is a scaled-up version of the final product.

Pyrolysis Conversion:

- Process: Place the polymer nanolattice in a vacuum furnace.

- Temperature: Heat to 900 °C.

- Outcome: The polymer converts to glassy carbon via pyrolysis. The structure undergoes isotropic shrinkage to approximately 20% of its original size, resulting in the final, ultra-strong carbon nanolattice with strut diameters of ~300 nm [3].

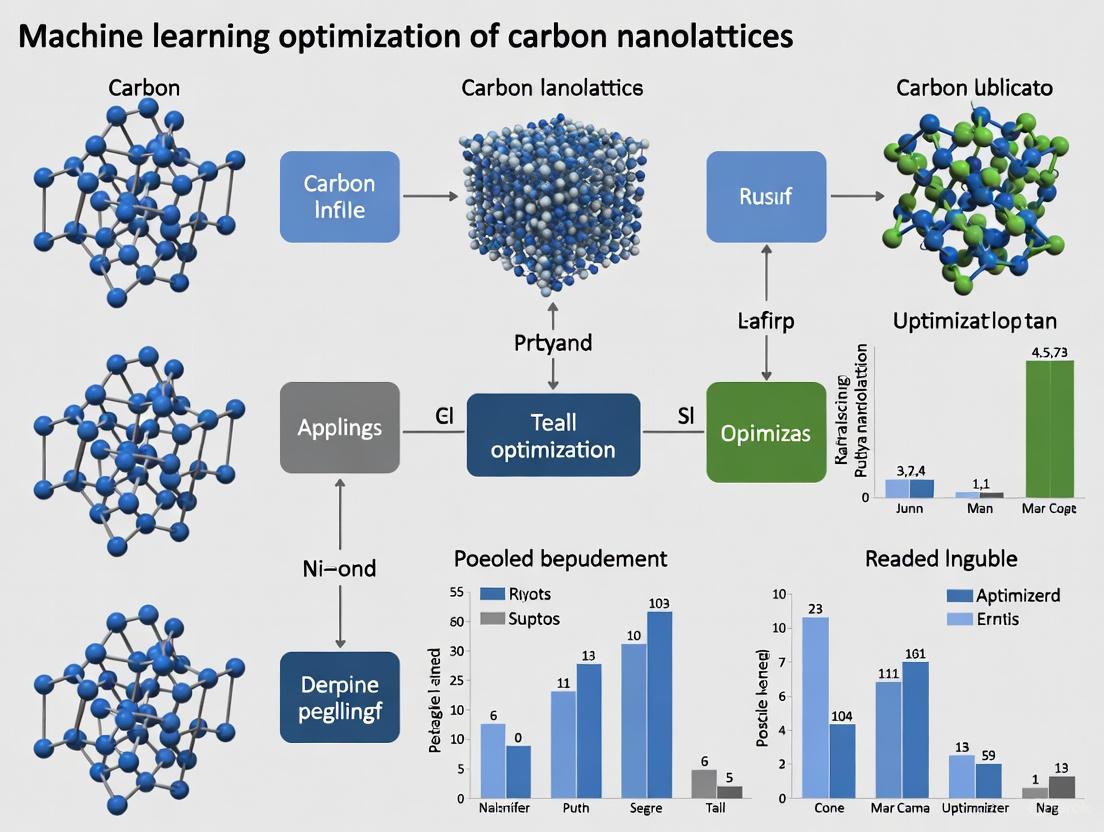

The workflow for this synthesis is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol 2: Probing the Size-Strength Relationship via In Situ Nanoparticle Compression

This protocol describes a method for directly observing the "smaller is stronger" effect and its limits in metal nanoparticles [11].

Sample Preparation:

- Materials: Au, Ag, or Pt nanoparticles with sizes ranging from 3 nm to 130 nm.

- Support: Deposit nanoparticles onto a substrate suitable for Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM).

In Situ Mechanical Testing:

- Equipment: In situ TEM holder equipped with a nanoindentation system.

- Process:

- Position a flat-punch diamond indenter tip above a single nanoparticle.

- Compress the nanoparticle while simultaneously recording a live TEM video.

- Continue compression until the nanoparticle undergoes catastrophic failure.

- Data Collection: Record the applied load and displacement to generate a stress-strain curve. Correlate the mechanical data with the direct visual observation of the failure mechanism (e.g., dislocation activity, diffusion, fracture).

Data Analysis:

- Strength Calculation: Calculate the compressive strength from the peak load in the stress-strain data.

- Mechanism Correlation: Link the calculated strength to the specific deformation mechanism observed in the TEM video for that particle size. This reveals the transition from dislocation-based plasticity to diffusive deformation [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions in nano-architected material research.

Table: Essential Materials for Nano-Architected Material Research

| Material / Solution | Function / Application | Key Details / Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Photosensitive Acrylic Resin | Base material for creating 3D nanostructures via Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) [3]. | Converts to glassy carbon during pyrolysis. The initial print is scaled to account for ~80% isotropic shrinkage [13]. |

| PureTube / IsoNanotube Aqueous Solutions | Provide pre-dispersed carbon nanotubes for composite integration or fundamental studies [14]. | Concentration: 0.25 mg/mL (PureTube) or 0.01 mg/mL (IsoNanotube). Shelf-life: Use within 3-6 months; check BIUB code. Contains surfactants that may require removal [14]. |

| Polystyrene Nanospheres | Model system for studying self-assembly and structural coloration phenomena at the nanoscale [15]. | Typical diameter ~400 nm. Can be self-assembled into monolayers and modified via reactive ion etching to tune optical properties [15]. |

| High-Purity Metal Precursors | Synthesis of metal nanoparticles (Au, Ag, Pt) for fundamental studies of size-dependent mechanical properties [11]. | Critical for producing nanoparticles (3-130 nm) with controlled size and purity for compression testing [11]. |

Visualizing the "Smaller is Stronger" Effect and Its Underlying Mechanisms

The relationship between size and mechanical strength at the nanoscale is complex and governed by competing deformation mechanisms, as illustrated below.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Identifying and Mitigating Geometric Stress Concentrations

Problem: A component with a sharp corner or a small fillet radius is failing prematurely under cyclic loading. Cracks are initiating at the geometric discontinuity.

Background: Stress concentrations are localized regions where stress is significantly higher than the surrounding nominal stress, quantified by the stress concentration factor (Kt = σmax / σnominal) [16] [17]. In traditional designs, sharp corners act as "stress raisers," where the theoretical stress can approach infinity as the radius of curvature approaches zero [16]. This leads to premature failure, especially under fatigue loading [18].

Investigation & Solution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify | Locate all sharp corners, small fillet radii, holes, or abrupt section changes in the load path [17]. | A list of potential high-risk stress risers. |

| 2. Analyze | Perform a Finite Element Analysis (FEA) with a convergence study. Refine the mesh at critical features until peak stress values stabilize [18]. | A accurate stress map identifying the maximum localized stress. |

| 3. Mitigate | Redesign the geometry to incorporate a large, smooth transition. Replace sharp corners with fillets whose radius is maximized relative to the connected features [17] [16]. | A significant reduction in peak stress and Kt. |

| 4. Validate | Re-run FEA on the modified design to confirm the reduction in peak stress. | A validated design with a more uniform stress distribution and higher predicted fatigue life. |

Example from Practice: In a roller support component, increasing a fillet radius from 0.010 inches to 0.080 inches reduced the localized stress from 14,419 psi to 3,873 psi, despite the more severe load case being in tension on the opposite side [17].

Guide: Addressing Premature Nodal Failure in Architected Materials

Problem: A traditional nanolattice structure with uniform struts is failing at the nodes (junctions) under compression, well below its theoretical strength.

Background: Standard lattice designs with uniform beam elements and sharp intersections are prone to stress concentrations at the nodes. This leads to early local failure, limiting the material's overall strength and stiffness [3] [12].

Investigation & Solution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Confirm Failure Mode | Use electron microscopy to examine fractured samples. Confirm that cracking initiates at the nodes. | Verified nodal failure as the primary failure mechanism. |

| 2. Optimize Geometry | Employ a multi-objective Bayesian optimization algorithm. The algorithm will non-intuitively redistribute material, often thickening struts near nodes and thinning them in mid-spans to create curved geometries [4] [3]. | A generative design that promotes uniform stress distribution and eliminates nodal stress concentrations. |

| 3. Fabricate & Test | Manufacture the optimized design using high-resolution 3D printing (e.g., two-photon polymerization) followed by pyrolysis to create a glassy carbon structure [6] [3]. | A experimentally validated nanolattice with significantly enhanced mechanical properties. |

Example from Practice: Using this approach, researchers created Bayesian-optimized carbon nanolattices that demonstrated a 118% increase in strength and a 68% improvement in Young's modulus compared to standard lattice geometries of the same density [6] [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between the stress concentration factor (Kt) and the stress intensity factor (KI)?

A: The stress concentration factor (Kt) is a dimensionless parameter used in linear-elastic analysis of uncracked components. It quantifies the amplification of stress due to geometric features like holes or notches [16]. In contrast, the stress intensity factor (KI) is a fracture mechanics parameter used for components with existing cracks. It quantifies the severity of the stress field near the crack tip and predicts whether the crack will grow [16].

Q2: Why does increasing the mesh density in my FEA model show stresses that keep rising without converging?

A: This is a classic sign of a stress singularity [18]. It occurs when modeling geometrically sharp re-entrant corners (e.g., a perfect 90-degree angle with no fillet). The theoretical stress at an infinitely sharp corner is infinite. The FEA model is correctly reflecting this mathematical reality, but the result is not physically meaningful. To obtain accurate results, you must model the actual fillet radius and perform a mesh convergence study on the filleted geometry [18].

Q3: My component is made from a ductile metal. How critical is it to accurately model stress concentrations for strength analysis?

A: The necessity for accuracy depends on the failure mode. For static loading of ductile materials, localized yielding at a stress concentration can redistribute stress without causing total failure. In such cases, a simplified analysis might suffice [18]. However, for fatigue analysis (cyclic loading), accurate peak stresses are crucial as they directly dictate the component's life. Similarly, for brittle materials, accurate peak stress is always critical for predicting failure under both static and dynamic loads [18].

Q4: What is the role of the "smaller is stronger" effect in nanoarchitected materials?

A: At the nanoscale, materials often exhibit a "smaller is stronger" effect because the probability of containing a critical-sized flaw decreases as the volume of material shrinks [12] [19]. For pyrolytic carbon nanolattices, reducing strut diameters to ~300 nm minimizes defects and, combined with a pyrolysis-induced gradient that creates a high-purity sp²-bonded carbon shell, leads to exceptional specific strength [6] [3].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Bayesian Optimization of Nanolattice Geometries

This protocol details the workflow for using machine learning to design nanolattices that are resistant to stress concentrations.

Diagram 1: AI-driven material design and fabrication workflow.

Procedure:

Generative Modeling:

- An initial set of 400 random lattice geometries is generated within a defined design space for strut length and shape [3].

- Finite Element Analysis (FEA) is used to simulate the linear elastic response of each geometry under compression and shear, calculating its relative density (ρ̄), effective Young's modulus (Ē), and effective shear modulus (μ̄) [3].

- A multi-objective Bayesian optimization (MBO) algorithm uses this high-quality dataset to iteratively explore the design space. It aims to maximize the hypervolume defined by the normalized mechanical properties while minimizing density, seeking the Pareto-optimal surface [3].

- The process runs until convergence (typically around 100 MBO-generated points), resulting in non-intuitive, optimized beam shapes that thicken near nodes and slenderize in mid-spans to eliminate stress concentrations [4] [3].

Fabrication via Two-Photon Polymerization & Pyrolysis:

- The optimized digital design is converted into a 3D unit cell and patterned into a larger lattice (e.g., 5x5x5 unit cells) [3].

- The structure is fabricated using a Nanoscribe Photonic Professional GT2 or similar two-photon polymerization (2PP) 3D printer. This system uses a photosensitive resin (e.g., IP-Dip photoresist) and writes the structure with voxels a few hundred nanometers wide, creating a polymeric nanolattice [6] [12] [19].

- The polymer structure is placed in a vacuum furnace and subjected to pyrolysis at 900°C. This process converts the cross-linked polymer into a glassy, sp²-rich pyrolytic carbon and shrinks the entire structure to about 20% of its original size, locking in the final nanoscale dimensions and gradient atomic architecture [3] [19].

Validation via Nano-compression Testing:

- The mechanical properties of the fabricated nanolattices are determined using nanoscale uniaxial compression tests [3].

- A nanoindenter or similar instrument is used to compress the sample while measuring the applied load and displacement.

- The resulting stress-strain data is used to calculate the compressive strength and Young's modulus of the optimized nanolattice [3].

Performance Data: Traditional vs. AI-Optimized Nanolattices

The following table summarizes the quantitative performance gains achieved by applying Bayesian optimization to carbon nanolattices, compared to traditional uniform designs.

Table 1: Mechanical performance comparison of traditional and AI-optimized nanolattices.

| Property | Traditional Uniform Lattices | Bayesian Optimized Lattices | Improvement | Test Conditions / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Strength | Varies by design | 2.03 MPa m³ kg⁻¹ [3] | >1 order of magnitude vs. many low-density materials [3] | Density: <215 kg m⁻³ |

| Compressive Strength | Baseline | 180–360 MPa [4] [6] [3] | Up 118% [6] [3] | Comparable to carbon steel [4] [3] |

| Young's Modulus | Baseline | 2.0–3.5 GPa [3] | Up 68% [6] [3] | Comparable to soft woods [3] |

| Density | ~125–215 kg m⁻³ | ~125–215 kg m⁻³ [3] | Unchanged (equivalent density comparison) | Comparable to Styrofoam/expanded polystyrene [6] [3] |

| Primary Failure Mode | Crack initiation at nodes [3] [12] | Uniform stress distribution; failure no longer nodal [4] | Shift from brittle to more robust failure | Observed during compression testing [4] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential research reagents and equipment for nanolattice experimentation.

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| IP-Dip Photoresist | A photosensitive polymer resin used as the base material for two-photon polymerization. It is cross-linked by the laser to form the initial 3D polymer scaffold [19]. |

| Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) System | A high-resolution 3D lithography technique (e.g., Nanoscribe Photonic Professional GT2) that enables direct laser writing of complex 3D structures with features down to a few hundred nanometers [6] [12]. |

| Multi-Focus 2PP Attachment | An upgrade to standard 2PP that uses multiple laser foci to print millions of unit cells in parallel, significantly increasing fabrication throughput for scalable production [6] [3]. |

| Tube Furnace | A high-temperature furnace used for the pyrolysis process. It heats the polymer lattice in a vacuum or inert atmosphere to ~900°C, converting it to pyrolytic carbon [3] [19]. |

| Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | The machine learning core that drives the generative design process. It efficiently explores the design space with minimal data to find geometries that optimally balance multiple mechanical objectives [3] [1]. |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) Software | Used to simulate the mechanical response (stress, strain, deformation) of virtual lattice models, providing the training data for the optimization algorithm [16] [3]. |

| Nanoindenter / Microtester | An instrument for mechanical characterization, used to perform uniaxial compression tests on the fabricated nanolattices to measure their Young's modulus and compressive strength [3]. |

The Confluence of Materials Science, AI, and Nanotechnology

Technical Support Center: Machine Learning Optimization of Carbon Nanolattices

This guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support for researchers working at the intersection of AI-driven design and nanoscale materials engineering, specifically for developing high-strength, lightweight carbon nanolattices.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

1. FAQ: Why does my machine learning model for nanolattice design require extensive computational resources and time? Troubleshooting Guide: This often stems from inefficient data handling or suboptimal algorithm selection.

- Problem: Model training is slow.

- Solution: Implement a Multi-objective Bayesian Optimization (MBO) algorithm. This method is designed to work effectively with smaller, high-quality datasets (e.g., around 400 data points), drastically reducing computational load compared to algorithms requiring tens of thousands of data points [1] [3].

- Problem: The model fails to predict geometries with improved mechanical properties.

- Solution: Ensure your training data incorporates multiple objectives simultaneously. The algorithm should be set up to optimize for competing goals, such as maximizing Young's modulus and shear modulus while minimizing density [3].

2. FAQ: My 3D-printed nanolattice structures show poor geometric fidelity, especially with complex, AI-designed curves. How can I improve this? Troubleshooting Guide: This is typically related to the limitations of the nanoscale additive manufacturing process.

- Problem: Strut warping or loss of detail, particularly for strut diameters approaching 300 nm.

- Solution: This may be a hardware limitation. Optimize the two-photon polymerization (2PP) parameters and note that further reducing strut diameters below 300 nm can lead to a loss of fidelity due to voxel print resolution and subsequent warping during pyrolysis [3].

- Problem: Non-conformal final geometry compared to the AI-generated model.

- Solution: Cross-validate the manufactured structure with the model using Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM). This helps identify specific stages (printing, pyrolysis) where geometric distortions are introduced [3].

3. FAQ: How can I address the "black box" nature of AI and gain physical insights from my nanolattice models? Troubleshooting Guide: This is a common challenge in AI for science.

- Problem: The AI suggests a high-performing geometry, but the physical reason for its performance is unclear.

- Solution: Couple your AI workflow with localized structural and atomic characterization. Techniques like FESEM and molecular dynamics simulations can reveal the physical mechanisms behind the performance, such as identifying a radial gradient of sp² bonding in pyrolytic carbon struts that contributes to enhanced strength [3].

- Problem: The model's predictions are not interpretable.

- Solution: Employ a "human-in-the-loop" system where the AI presents its observations and hypotheses in natural language, allowing researchers to integrate their domain expertise [20].

4. FAQ: My experimental results for nanolattice strength and stiffness are inconsistent and not reproducible. Troubleshooting Guide: Irreproducibility can be caused by subtle variations in synthesis and processing.

- Problem: Inconsistent material properties between batches.

- Solution: Integrate computer vision and vision language models to monitor experiments in real-time. These systems can detect millimeter-scale deviations in sample shape or procedural errors and suggest corrective actions [20].

- Solution: Meticulously control the pyrolysis process. The conversion of polymer to glassy aromatic carbon at high temperatures (e.g., 900°C) must be highly consistent, as it affects the final carbon purity and atomic structure [3].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Bayesian-Optimized Carbon Nanolattice Workflow

The following protocol is adapted from research that achieved carbon nanolattices with the strength of carbon steel at the density of Styrofoam [3].

Generative Modeling via Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization

- Input: Define a base lattice structure (e.g., Cubic-Face Centered Cubic - CFCC).

- Parameterization: Break the lattice into constituent struts. Represent each strut's profile using a Bézier curve controlled by four randomly distributed points within the design space.

- Data Generation: Use Finite Element Analysis (FEA) on 400 randomly generated geometries to calculate three key properties:

- Relative density (( \bar{\rho} ))

- Effective Young's Modulus (( \bar{E} ))

- Effective Shear Modulus (( \bar{\mu} ))

- Optimization: The MBO algorithm iteratively expands a 3D hypervolume defined by the normalized values of the three properties above. The goal is to identify the Pareto optimum surface, maximizing the multi-objective function ( [\frac{\bar{E}}{\bar{\rho}} \cdot \frac{\bar{\mu}}{\bar{\rho}}]^{0.5} ) for combined compressive and shear performance.

Nanoscale Additive Manufacturing

- Process: Use Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) to fabricate the AI-designed lattice from a photocurable acrylic polymer resin.

- Output: A 3D polymeric nanostructure that is a precise replica of the computational model.

Pyrolysis Conversion to Carbon

- Process: Heat the polymeric structure in an inert atmosphere to 900°C.

- Result: The polymer pyrolyzes, converting into a glassy, aromatic carbon structure. The final part shrinks to approximately 20% of its original size, achieving strut diameters as low as 300 nm.

Mechanical Characterization & Validation

- Test: Perform nanoscale uniaxial compression tests on the pyrolyzed carbon nanolattices.

- Measure: Record the experimental Young's Modulus (E) and compressive strength (σ) and compare them against the model's predictions and standard (non-optimized) lattices of equivalent density.

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The diagram below outlines the key stages of the Bayesian-optimized carbon nanolattice development process.

Quantitative Performance Data of Optimized Carbon Nanolattices

The table below summarizes the experimentally measured performance enhancements achieved through the Bayesian optimization of carbon nanolattices, benchmarked against standard designs [3].

Table 1: Experimental Mechanical Properties of MBO-Optimized vs. Standard Carbon Nanolattices

| Lattice Type | Strut Diameter | Density (kg/m³) | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Specific Strength (MPa m³/kg) | Key Improvement Over Standard Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFCC MBO-3 | 600 nm | 180 | 3.5 | 360 | 2.03 | Strength increased by 118% |

| CFCC MBO-1 | 600 nm | 215 | 3.2 | 295 | 1.37 | Stiffness increased by 68% |

| CFCC Standard | 600 nm | ~180 | ~2.0 | ~165 | ~0.92 | Baseline for comparison |

| CBCC MBO | 300 nm | 125 | 2.0 | 180 | 1.44 | Strength enhanced by 79% (vs. 600nm) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Equipment for AI-Optimized Carbon Nanolattice Research

| Item | Function / Role in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Photocurable Acrylic Polymer Resin | The base material for two-photon polymerization (2PP); forms the initial 3D nanostructure [3]. |

| Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | The core AI software that generates optimal lattice geometries by efficiently navigating the complex design space with multiple competing objectives [3]. |

| Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) System | A high-precision nanoscale 3D printer that uses a laser to solidify the polymer resin into the complex AI-designed lattice structures [1] [3]. |

| Tube Furnace (Inert Atmosphere) | Used for the pyrolysis step, heating the polymer structure to 900°C in an oxygen-free environment to convert it into a pure, glassy carbon structure [3]. |

| Nanoindenter / Microcompression Tester | Equipment for mechanically characterizing the pyrolyzed nanolattices, measuring critical properties like Young's modulus and compressive strength [3]. |

| Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FESEM) | Used for high-resolution imaging to validate the printed geometry, measure strut diameters, and inspect for defects before and after mechanical testing [3]. |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) Software | Generates the initial training data for the AI model by simulating the mechanical response (density, Young's modulus, shear modulus) of thousands of virtual lattice designs [3]. |

Leveraging AI for Predictive Material Design and Biomedical Applications

Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO) has emerged as a powerful data-efficient machine learning strategy for optimizing multiple, often competing, black-box objective functions when evaluations are expensive. This approach is particularly valuable in scientific domains where experimental data is scarce and computational resources are limited. By combining probabilistic modeling with intelligent decision-making, MOBO sequentially selects the most informative experiments to perform, rapidly converging toward optimal solutions while minimizing resource consumption.

In materials science and drug discovery, researchers frequently face scenarios where multiple performance metrics must be balanced simultaneously. For instance, when designing carbon nanolattices, engineers must optimize for both strength and lightweight properties, while drug developers might seek compounds that maximize efficacy while minimizing toxicity. Traditional experimentation approaches would require exhaustive testing of countless possibilities, but MOBO strategically navigates these complex design spaces by building surrogate models of objective functions and using acquisition functions to guide the selection of promising candidates. This methodology has demonstrated remarkable success in applications ranging from the development of ultra-strong carbon nanolattices to the design of novel pharmaceutical compounds, establishing itself as an indispensable tool for modern research and development.

Core Concepts of Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization

Foundational Principles

MOBO extends standard Bayesian optimization to scenarios with multiple competing objectives. The fundamental goal is to identify the Pareto-optimal set - a collection of solutions where no objective can be improved without worsening at least one other objective. Formally, a solution ( x^* ) is Pareto-optimal if there does not exist another solution ( x' ) such that ( fi(x') \leq fi(x^) ) for all objectives ( i ) and ( f_j(x') < f_j(x^) ) for at least one objective ( j ) [21].

Unlike single-objective optimization that converges to a single optimum, MOBO maps the entire Pareto front - the multidimensional surface representing the best possible trade-offs between objectives. This provides decision-makers with a comprehensive view of available options and their inherent compromises. The methodology is particularly valuable when objective functions are expensive to evaluate, as it minimizes the number of experiments required to characterize these trade-offs.

Key Methodological Components

MOBO employs several interconnected components to efficiently navigate complex design spaces:

Surrogate Modeling: Gaussian Processes (GPs) typically model each expensive black-box objective function, providing both predictions and uncertainty estimates for unexplored regions of the design space [21]. These probabilistic models capture our belief about each objective's behavior between experimental observations.

Acquisition Functions: Specialized functions balance exploration and exploitation to recommend the most promising candidates for subsequent evaluation. The Expected Hypervolume Improvement (EHVI) is a prominent Pareto-compliant acquisition function that measures the expected increase in the volume dominated by the Pareto set when adding a new point [21].

Preference Integration: Advanced MOBO frameworks incorporate user preferences to focus computational resources on relevant regions of the Pareto front. This includes preference-order constraints that prioritize certain objectives and utility-based methods that learn decision-maker preferences through interactive feedback [21].

MOBO in Practice: Carbon Nanolattices Case Study

Experimental Framework and Workflow

The application of MOBO to carbon nanolattice development demonstrates its transformative potential in materials science. Researchers at the University of Toronto employed a sophisticated workflow combining computational optimization with advanced manufacturing to create nanolattices with exceptional specific strength [22] [6] [23].

Table: Key Performance Metrics of Bayesian-Optimized Carbon Nanolattices

| Performance Metric | Traditional Design | MOBO-Optimized | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Strength (MPa m³ kg⁻¹) | Not reported | 2.03 | Benchmark |

| Density (kg m⁻³) | Not reported | <215 | Maintained low |

| Strength | Baseline | +118% | Significant |

| Young's Modulus | Baseline | +68% | Substantial |

| Compressive Strength (MPa) | Not applicable | 180-360 | Comparable to carbon steel |

The optimization process targeted both maximal mechanical strength and minimal density, two naturally competing objectives. Through iterative design refinement, the MOBO algorithm successfully identified lattice geometries that distributed stress more uniformly, eliminating nodal stress concentrations that caused premature failure in conventional designs [22] [6].

Material Synthesis and Characterization Protocols

The experimental realization of optimized nanolattice designs involved sophisticated fabrication and processing techniques:

Two-Photon Polymerization Direct Laser Writing: A high-resolution 3D printing technique that uses UV-sensitive resin added layer by layer, where the material becomes a solid polymer at points where two photons meet [24] [6]. This approach enabled the creation of intricate lattice structures with plate faces as thin as 160 nanometers.

Pyrolysis Transformation: The 3D-printed polymer structures underwent pyrolysis at 900°C in a vacuum for one hour, converting them to glassy carbon with superior mechanical properties [6]. This process induced an atomic gradient of 94% sp² aromatic carbon with low oxygen impurities, significantly enhancing structural integrity [22] [23].

Scalable Manufacturing: Researchers implemented multi-focus multi-photon polymerization to produce millimeter-scale metamaterials consisting of 18.75 million lattice cells with nanometer dimensions, addressing previous challenges in production scalability [22].

The resulting carbon nanolattices achieved an exceptional specific strength of 2.03 MPa m³ kg⁻¹ at densities below 215 kg m⁻³, demonstrating strength comparable to carbon steel while maintaining a density similar to expanded polystyrene [22] [6] [23].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Materials for MOBO-Guided Nanolattice Development

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|

| UV-Sensitive Resin | Primary material for two-photon polymerization | Polymerizes at two-photon meeting points; enables intricate 3D nanostructures [24] |

| Pyrolytic Carbon | Final structural material | Formed through pyrolysis at 900°C; exhibits 94% sp² aromatic carbon content [22] [6] |

| Glassy Carbon | High-strength nanolattice composition | Result of pyrolysis process; provides exceptional strength-to-weight ratio [6] |

| Two-Photon Lithography System | Nanoscale 3D printing | Enables creation of features down to 160 nm; critical for lattice fabrication [24] [6] |

| Vacuum Furnace | Pyrolysis processing | Maintains oxygen-free environment at 900°C for structural transformation [6] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Theoretical Foundations

Q: How does Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization differ from traditional optimization approaches? A: Unlike traditional gradient-based methods or grid searches, MOBO is specifically designed for scenarios where objective functions are expensive to evaluate (computationally or experimentally), lack known analytical forms, and involve multiple competing metrics. MOBO builds probabilistic surrogate models of these black-box functions and uses acquisition functions to sequentially select the most informative experiments, dramatically reducing the number of evaluations needed to identify optimal trade-offs [21].

Q: What is the Pareto front and why is it important? A: The Pareto front represents the set of optimal trade-offs between competing objectives - solutions where improving one objective necessarily worsens another. Identifying this front is crucial for informed decision-making, as it provides a comprehensive view of available options and their inherent compromises. In carbon nanolattice design, the Pareto front reveals the fundamental trade-off between strength and density, allowing researchers to select designs appropriate for specific applications [21].

Implementation Considerations

Q: What are the most common acquisition functions in MOBO and how do I choose? A: The Expected Hypervolume Improvement (EHVI) is a popular Pareto-compliant acquisition function that measures expected improvement in the volume dominated by the Pareto set [21]. Alternative approaches include random scalarization (ParEGO) and information-theoretic measures. Selection depends on your specific context: EHVI generally performs well but has computational overhead; scalarization approaches are simpler but may miss concave Pareto regions; information-theoretic methods prioritize uncertainty reduction.

Q: How can I incorporate domain knowledge or preferences into MOBO? A: Preference-aware MOBO strategies allow integration of domain knowledge through preference-order constraints (specifying that one objective is more important than another) or utility-based methods that learn decision-maker preferences [21]. For carbon nanolattices, researchers might prioritize strength over density for structural applications, constraining the search to regions of the design space that reflect this preference.

Troubleshooting Guide

Optimization Performance Issues

Problem: Slow convergence or poor Pareto front approximation

Insufficient Surrogate Model Flexibility: Standard Gaussian Processes with common kernels may struggle with complex, high-dimensional objective functions. Solution: Implement more flexible surrogate models such as deep kernel learning or ensemble approaches that can capture intricate response surfaces. In nanolattice optimization, this might involve developing custom kernels that incorporate physical knowledge of stress distribution.

Inadequate Exploration-Exploitation Balance: Overly greedy acquisition functions may converge to local optima. Solution: Adjust acquisition function parameters to increase exploration, particularly in early optimization rounds. The Hypervolume Improvement-based approaches automatically balance this, but parameters governing uncertainty weight might need tuning [21].

Problem: Computational bottlenecks in high-dimensional spaces

Curse of Dimensionality: Standard MOBO becomes computationally expensive as design dimensions increase. Solution: Implement trust region methods (like MORBO) that partition the space into local regions modeled by separate GPs, reducing cubic computational costs [21]. For nanolattice design, leverage symmetry and periodicity to reduce effective dimensionality.

Batch Selection Inefficiencies: Sequential evaluation becomes impractical with parallel experimental capabilities. Solution: Employ batch selection strategies with diversity penalties that ensure proposed experiments are spread across both design space and objective space [21].

Experimental Integration Challenges

Problem: Discrepancy between model predictions and experimental results

Model Inadequacy for Extreme Designs: Surrogate models may perform poorly when extrapolating beyond the data range. Solution: Implement conservative design selection with constraints that prevent evaluation of radically different designs until model uncertainty is reduced. In nanolattice fabrication, this might involve gradually expanding the design space as model confidence increases.

Stochastic Experimental Outcomes: Noisy measurements obscure true objective function values. Solution: Incorporate noise-aware GP models that explicitly account for observation uncertainty. For mechanical testing of nanolattices, this might involve repeated measurements at key design points to characterize variability.

Problem: Scalability limitations in fabrication and testing

Manufacturing Constraints Overlooked: Optimized designs may be theoretically sound but practically unfabricatable. Solution: Incorporate manufacturing constraints directly into the optimization framework as feasibility constraints. In nanolattice development, this includes minimum feature size limitations of two-photon polymerization systems [6].

Experimental Throughput Limitations: Physical experiments cannot keep pace with optimization recommendations. Solution: Implement asynchronous MOBO frameworks that update models as results become available and strategically select designs that provide maximal information per experiment [21].

Advanced Methodologies and Future Directions

Emerging MOBO Extensions

The MOBO landscape continues to evolve with several advanced methodologies addressing specific challenges:

Multi-Objective Causal Bayesian Optimization (MO-CBO): This extension incorporates causal relationships between variables to identify optimal interventions more efficiently. By leveraging causal graph structures, MO-CBO reduces the search space and decomposes complex problems into simpler multi-objective optimization tasks [25].

Coverage Optimization for Collective Performance: Rather than identifying a complete Pareto front, this approach finds a small set of solutions that collectively "cover" multiple objectives. In drug discovery, this might involve identifying a limited number of antibiotics that collectively treat a wide range of pathogens [26].

Non-Myopic and RL-Based Sequence Planning: Recent advances employ reinforcement learning and transformer models to plan sequences of evaluations, considering long-term optimization trajectories rather than just immediate gains. These approaches demonstrate improved Pareto front recovery within tight evaluation budgets [21].

Application Frontiers

MOBO is expanding into increasingly sophisticated domains:

Drug Discovery and Molecular Design: AI-powered molecular innovation leverages MOBO to balance multiple drug properties simultaneously, such as efficacy, safety, and synthesizability. The generative AI drug discovery market is projected to reach $1.7 billion in 2025, with MOBO playing a critical role in de novo molecular design [27].

Personalized Medicine and Therapeutic Optimization: MOBO frameworks are being adapted to optimize treatment regimens for individual patients, balancing therapeutic benefits against side effects and personal tolerance levels [27].

Sustainable Material Development: The methodology is increasingly applied to green chemistry and material science, optimizing for both performance and environmental impact metrics such as energy efficiency, recyclability, and carbon footprint [27].

As MOBO methodologies continue to mature, their integration with experimental science promises to accelerate innovation across numerous domains, from ultra-strong nanomaterials to life-saving pharmaceuticals, demonstrating the transformative potential of data-efficient optimization strategies.

Generative Modeling and Finite Element Analysis (FEA) for Virtual Prototyping

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of combining generative modeling with FEA in nanolattice research?

A1: The integration allows for the automated discovery of high-performance nanolattice geometries that are often non-intuitive. Multi-objective Bayesian optimization uses FEA-derived data to generate designs that maximize specific strength and stiffness while minimizing density, leading to experimental improvements of up to 118% in strength and 68% in stiffness compared to standard lattices [3].

Q2: Our FEA predictions for nanolattice failure do not match experimental results. What could be causing this discrepancy?

A2: This is commonly due to oversimplified material properties in the FEA model. Unlike bulk materials, nanoscale pyrolytic carbon exhibits a radial atomic gradient and a high concentration of sp² aromatic bonds (94%) in the outer shell, significantly influencing mechanical behavior [3]. Ensure your FEA input properties are calibrated from nanoscale tests on printed and pyrolyzed structures, not bulk material data sheets.

Q3: Why is Bayesian Optimization particularly suited for this design workflow compared to other ML algorithms?

A3: Bayesian Optimization is highly data-efficient, capable of identifying optimal designs with a small, high-quality dataset (e.g., ~400 FEA simulations) [1] [3]. This is crucial because generating each FEA data point for complex nanolattices is computationally expensive. It effectively explores the design space and predicts geometries that balance multiple competing objectives, such as compression strength, shear modulus, and density [3].

Q4: We observe warping and loss of geometric fidelity during the pyrolysis step. How can this be mitigated?

A4: Warping is often a result of non-uniform shrinkage or thermal gradients. Strategies to mitigate this include:

- Strut Diameter: Avoid strut diameters below 300 nm, as this can push against the limits of print resolution and lead to failure during pyrolysis [3].

- Process Control: Implement a controlled, slow pyrolysis ramp rate to minimize internal stresses.

- Design Compensation: Account for the ~80% volumetric shrinkage during pyrolysis in the initial generative design phase by pre-scaling the digital model [4].

Q5: What are the key computational resource requirements for running these coupled simulations?

A5: While cloud-solving can offload resources, local FEA setup for complex nanolattices demands substantial power. General recommendations include [28]:

- RAM: 16 GB or higher (32 GB recommended for desktops).

- Software: Professional-grade FEA software (e.g., Autodesk Nastran, Ansys) capable of handling non-linear material models and large-scale problems.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Generative Model Produces Geometries That Are Unmanufacturable

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Overly complex curves/angles violating 3D printer resolution. | Constrain the generative algorithm's design space (e.g., limit curvature radius, enforce minimum feature size >300 nm) [3]. |

| Unsupported overhangs in the generated design. | Integrate manufacturability checks (support structure need analysis) within the optimization loop. |

Issue: FEA Simulation Fails to Converge

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Poor quality mesh with highly distorted elements. | Refine the mesh, especially at node junctions where stress concentrates. Use a finer mesh density and check element quality metrics [28]. |

| Incorrect or unphysical boundary conditions applied to the model. | Revisit and simplify boundary conditions to ensure they accurately represent the physical compression/shear test setup. |

Issue: High Variance in Experimental Strength of Printed Nanolattices

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Inconsistent strut diameter due to printing or pyrolysis defects. | Calibrate the Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) system and optimize laser power/exposure time. Characterize printed struts via SEM to ensure uniformity [3]. |

| Contamination or impurities in the carbon structure post-pyrolysis. | Control the pyrolysis environment (inert gas flow) to achieve low oxygen impurities, which is critical for high strength [3]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Workflow for ML-Driven Design and Validation of Carbon Nanolattices

This protocol details the end-to-end process for creating and testing AI-optimized carbon nanolattices, as demonstrated in foundational research [3].

ML-FEA Integration Workflow

1. Define Objectives and Constraints:

- Objectives: Typically, to maximize effective Young's Modulus ((E)) and shear modulus ((\mu)) while minimizing relative density ((\bar{\rho})) [3].

- Constraints: Define the printable strut diameter range (e.g., 300–600 nm) and the maximum unit cell size.

2. Generate Initial Training Data with FEA:

- Randomly generate a set of initial lattice geometries (e.g., 400 designs) within the defined design space [3].

- For each geometry, run FEA simulations to calculate its relative density, effective Young's modulus under compression, and effective shear modulus.

- FEA Settings: Use linear elastic material properties for the polymer precursor. Apply appropriate boundary conditions and meshing to capture stress concentrations at nodes.

3. Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MBO):

- Use an MBO algorithm to iteratively expand a 3D hypervolume based on the normalized ((E), (\mu), (\bar{\rho})) data.

- The algorithm will propose new geometries that are predicted to lie on the "Pareto front" – the set of optimal trade-off designs [3].

- After a set number of iterations (e.g., 100), select the top-performing generative designs from the Pareto surface.

4. Fabrication via Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP):

- Convert the optimal digital designs into a 3D model patterned into a lattice (e.g., 5x5x5 unit cells).

- Use a 2PP nanoscale 3D printer to fabricate the structure from a photosensitive acrylic resin. This process uses a focused laser to solidify the resin at precise points, creating features with diameters as small as 300 nm [3].

5. Pyrolysis:

- Place the printed polymer lattice in a furnace with an inert atmosphere (e.g., argon or nitrogen).

- Heat to 900°C using a controlled temperature ramp. This process converts the organic polymer into a glassy, sp²-rich aromatic carbon material and shrinks the structure to approximately 20% of its original size [3] [4].

6. Mechanical Validation:

- Perform uniaxial compression tests on the pyrolyzed carbon nanolattices using a nanoindenter or similar instrument.

- Measure the experimental Young's modulus (E) and compressive strength (σ) for direct comparison with the FEA predictions.

Protocol 2: Key FEA Setup for Nanolattice Analysis

1. Geometry and Meshing:

- Import the generative model. Use a tetrahedral or hex-dominant mesh.

- Apply a mesh refinement at the nodes and junctions, which are critical stress concentration points [29] [28].

- Perform a mesh sensitivity analysis to ensure results are not dependent on element size.

2. Material Properties:

- For polymer precursor: Use linear elastic properties typical of the specific acrylic resin.

- For pyrolytic carbon: Use properties derived from tested nanopillars. Key properties include: High Young's Modulus and linear-elastic behavior until brittle fracture [3]. Note: These properties are size-dependent and must be empirically determined for your specific process.

3. Boundary Conditions and Loading:

- Fix the bottom surface of the lattice.

- Apply a displacement-controlled load to the top surface to simulate uniaxial compression.

- For shear modulus analysis, apply appropriate shear displacements.

4. Solving and Post-Processing:

- Run a static structural analysis.

- Analyze results for total deformation, von Mises stress (to identify yield regions), and strain energy.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

The following table details key materials and equipment used in the featured research on machine learning-optimized carbon nanolattices [3].

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) System | Enables nanoscale 3D printing of initial polymer lattices with strut diameters of 300-600 nm [3]. |

| Photosensitive Acrylic Resin | The polymer precursor used in 2PP to create the "green" body of the nanolattice [3]. |

| Tube Furnace (Inert Atmosphere) | Used for the pyrolysis step, converting the polymer lattice to carbon at 900°C in a controlled environment [3]. |

| Nanoindenter / Micromechanical Tester | Measures the mechanical properties (Young's modulus, compressive strength) of the final pyrolyzed nanolattices [3]. |

| Finite Element Analysis Software | Simulates the mechanical performance of generative designs to create data for the ML algorithm [28] [3]. |

| Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | The core ML tool that efficiently explores the design space to discover optimal lattice geometries [1] [3]. |

| Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FESEM) | Used for high-resolution imaging to verify print fidelity, strut diameter, and structural integrity post-pyrolysis [3]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center addresses common challenges encountered in the fabrication of carbon nanolattices via Two-Photon Polymerization (TPP) and pyrolysis, a process critical for advancing research in machine learning-optimized materials.

Fabrication Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem Phenomenon | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Delamination or Cracking during Pyrolysis | Excessive internal stress in the polymer precursor; mismatch of thermal expansion coefficients with substrate; overly rapid heating rate. | Inspect pre-pyrolysis structure for existing cracks or warping using SEM. Check pyrolysis furnace temperature profile and ramp rates. | Implement a slower, multi-stage pyrolysis ramp (e.g., 5°C/min to 300°C, 1h dwell, then 5°C/min to 900°C, 1h dwell) [30]. Ensure use of adhesion promoters on substrate [31]. |

| Uncontrolled or Non-Uniform Shrinkage | Inconsistent TPP exposure parameters; non-uniform polymer cross-linking; geometry-dependent shrinkage effects. | Measure feature sizes (e.g., beam diameters) pre- and post-pyrolysis using SEM. Correlate shrinkage with laser power and scanning speed settings. | Calibrate shrinkage factors for specific geometries. For SU-8, expect ~75% volumetric shrinkage; adjust original CAD model to compensate [30]. Optimize TPP laser power and scan speed for uniform exposure. |

| Structure Buckling or Collapse | High aspect ratio structural elements (e.g., >30:1); insufficient mechanical strength to withstand pyrolysis-induced stresses. | Calculate aspect ratio (length/diameter) of beams. Visually inspect for Euler buckling modes post-pyrolysis. | Redesign the nanolattice to reduce the aspect ratio of beams. For necessary high-aspect-ratio features, increase the TPP exposure dose to create thicker, stronger polymer beams [30]. |

| Failure to Achieve Target Resolution (< 200 nm) | Sub-optimal TPP exposure parameters; diffraction-limited laser spot; unsuitable photoresist. | Print and develop test structures (e.g., single lines) at varying laser powers and scan speeds to find the polymerization threshold. | Use high-resolution resins like IP-Dip or SZ2080. Operate the laser at the minimum power required for polymerization to minimize voxel size. Post-pyrolysis shrinkage can further enhance resolution [32] [31]. |

| Poor Carbon Quality or Mechanical Weakness after Pyrolysis | Incomplete carbonization due to insufficient final temperature or time; oxygen contamination during pyrolysis. | Perform Raman spectroscopy on pyrolyzed sample to assess the D/G band ratio, indicating carbon structure quality. | Ensure pyrolysis reaches a minimum of 900°C in a high-purity inert gas (Argon/Nitrogen) atmosphere with sufficient dwell time (e.g., 1 hour) [30] [19]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How much shrinkage should we anticipate during pyrolysis, and how can we design for it?

Shrinkage is a fundamental characteristic of the pyrolysis process and must be accounted for in the initial design phase. The degree of shrinkage is dependent on the photoresist, pyrolysis parameters, and the structure's geometry.

- Quantitative Data: The table below summarizes typical shrinkage values for common photoresists based on research findings [30] [31].

| Photoresist | Pyrolysis Temperature | Volumetric Shrinkage | Linear Shrinkage (Approx.) | Resulting Material |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP-Dip | 900°C | Up to 75% [30] | Varies by geometry | Glassy Carbon [31] |

| SZ2080 | 690°C | ~70% [31] | ~40% [31] | Ceramic (Si-Zr-O) [31] |

| OrmoComp | 450°C | ~40% [31] | ~20% [31] | Not Fully Carbonized [31] |

- Design Protocol: To compensate, you must inversely scale your original CAD model. For instance, if a 80% linear shrinkage is expected, the TPP structure should be fabricated at 500% of the target final size. Empirical calibration for your specific resin and geometry is essential.

Q2: Our structures consistently detach from the silicon substrate during pyrolysis. How can we improve adhesion?

Adhesion failure is a common issue due to stress buildup during thermal degradation. The following protocol can significantly improve adhesion [31]:

- Substrate Preparation: Meticulously clean the silicon wafer with acetone, isopropyl alcohol, and distilled water.

- Surface Activation: Treat the substrate with an oxygen plasma or "piranha solution" (a 3:1 mixture of concentrated sulfuric acid and hydrogen peroxide) for 30 minutes. Warning: Piranha solution is extremely corrosive and must be handled with extreme care.

- Adhesion Promoter: Apply an appropriate silane-based adhesion promoter (e.g., (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane) to the activated substrate before spin-coating the photoresist.

Q3: What is the typical pyrolysis protocol to convert IP-Dip polymer structures into glassy carbon?

A standard and reliable protocol for achieving high-quality glassy carbon from IP-Dip is as follows [30]:

- Atmosphere: Continuous flow of high-purity argon (or nitrogen) to maintain an inert environment and prevent oxidation.

- Temperature Ramp:

- Heat from room temperature to 300°C at a slow ramp rate of 5°C per minute.

- Hold at 300°C for 1 hour to facilitate gradual degassing and prevent violent decomposition.

- Continue heating from 300°C to 900°C at 5°C per minute.

- Hold at 900°C for 1 hour to ensure complete carbonization.

- Allow the furnace to cool down slowly to room temperature naturally.

Q4: How can machine learning be integrated into this fabrication workflow to optimize the process?

Machine learning (ML) serves as a powerful tool to navigate the complex parameter space of TPP and pyrolysis, accelerating the discovery of optimal designs and processes [19] [33] [6].

- Objective: An ML model, such as Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MBO), can be trained to find the ideal balance between competing goals, like maximizing mechanical strength while minimizing density.

- Input Parameters: The model considers design parameters (e.g., beam diameter, unit cell topology) and fabrication parameters (e.g., TPP laser power, pyrolysis temperature).

- Output: The ML algorithm suggests new parameter sets to test, which are then fabricated and mechanically characterized. The results are fed back to the model, creating a closed-loop optimization cycle that rapidly converges on the best-performing structures without exhaustive trial-and-error.

Machine Learning-Optimized Fabrication Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Role in Fabrication | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| IP-Dip Photoresist | An acrylic-based, negative-tone photoresist for high-resolution TPP. It carbonizes into glassy carbon during pyrolysis [31]. | Excellent for creating complex 3D structures with fine features (~100-200 nm). The resulting carbon has a high sp² content and good mechanical properties [19]. |

| SZ2080 Photoresist | A hybrid organic-inorganic sol-gel photoresist. Upon pyrolysis, it transforms into a ceramic material (based on Si-Zr-O) rather than carbon [31]. | Known for low shrinkage during TPP and high mechanical and thermal stability post-pyrolysis. Requires pre-baking before TPP fabrication [31]. |

| OrmoComp Photoresist | A hybrid organic-inorganic photoresist (ORMOCER). It is biocompatible and suitable for optical applications but is not ideal for pure carbon structures [31]. | Does not fully carbonize; at 450°C it shrinks significantly but retains an organic-inorganic hybrid composition [31]. |

| PGMEA (Propylene Glycol Monomethyl Ether Acetate) | A standard developer for IP-Dip photoresist. It dissolves the non-polymerized areas after TPP exposure [31]. | Typical development time is 20-30 minutes, followed by rinsing in isopropyl alcohol. Must be handled in a well-ventilated area. |

| Adhesion Promoters (e.g., Silanes) | Chemicals applied to the substrate (e.g., silicon wafer) to create a strong covalent bond between the substrate and the photoresist [31]. | Critical for preventing delamination during the development and pyrolysis steps. Common types include amino-silanes for epoxy-based resists. |

This technical support center provides essential guidance for researchers working at the intersection of machine learning (ML)-optimized material design and advanced drug delivery systems. The core thesis explores how the exceptional properties of ML-designed carbon nanolattices—notably their ultra-light weight and high strength—can be functionally translated into next-generation therapeutic carriers. This involves a paradigm shift from traditional, passive drug carriers to active, "smart" systems where the carrier itself contributes to the therapeutic outcome [34] [35].

The following sections address specific experimental challenges, provide detailed protocols, and list critical reagents to support your research in this emerging field.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: How can we adapt the high strength-to-weight ratio of carbon nanolattices for drug delivery applications?

The high strength-to-weight ratio, a key feature of ML-optimized carbon nanolattices [1], is directly translatable to drug delivery. This property allows for the design of carriers that are robust enough to survive the circulatory system and reach their target, yet light enough for efficient distribution. Furthermore, the extensive surface area and porosity inherent in these nanolattices can be harnessed for high-capacity drug loading, moving towards minimal-carrier drug delivery systems (MCDDS) that reduce excipient burden and potential toxicity [35].

FAQ 2: Our nanocarrier shows high drug loading but premature release. How can this be resolved?

Premature release is a common challenge when using highly porous carriers. Solution strategies include:

- Stimuli-Responsive Gatekeeping: Incorporate a stimuli-sensitive coating or moieties that remain sealed during circulation but open at the target site. For example, diselenide-containing nanocarriers disassemble and release their payload upon exposure to the high ROS levels found in the tumor microenvironment [34].

- Surface Functionalization: Cloak the nanolattice with a cancer-cell-derived membrane fragment. This biomimetic approach can enhance target specificity and prevent off-target release [34].

- Cross-linking: Gently cross-link the porous structure of the carrier using biodegradable linkers (e.g., disulfide bonds) that break under specific biological conditions, thereby controlling the release kinetics [36].

FAQ 3: We are encountering high toxicity with our first-generation nanocarrier. What are the potential causes?

Toxicity can stem from the carrier material itself or its degradation products. To address this: