Machine Learning and Nano-3D Printing Unlock Ultra-Light, High-Strength Carbon Nanolattices for Biomedicine

This article explores the revolutionary convergence of machine learning, nanoscale 3D printing, and material science in creating carbon nanolattices—materials possessing the strength of carbon steel and the density of Styrofoam.

Machine Learning and Nano-3D Printing Unlock Ultra-Light, High-Strength Carbon Nanolattices for Biomedicine

Abstract

This article explores the revolutionary convergence of machine learning, nanoscale 3D printing, and material science in creating carbon nanolattices—materials possessing the strength of carbon steel and the density of Styrofoam. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we detail the foundational principles of these nano-architected materials, the advanced manufacturing methodologies like two-photon polymerization, and the AI-driven optimization processes that overcome traditional geometric limitations. The scope extends to their validation through exceptional mechanical performance and their emerging, transformative potential in biomedical applications, including tissue engineering scaffolds and advanced drug delivery systems.

What Are Carbon Nanolattices? Defining the Next Generation of Mechanical Metamaterials

Nanoarchitected materials represent a frontier in metamaterial design, where properties are derived not only from the base material composition but also from the intricate geometry of nanoscale structures. Among these, carbon nanolattices have set remarkable benchmarks for mechanical performance, achieving conflicting property combinations previously thought impossible. These synthetic porous materials consist of nanometer-scale members patterned into ordered, three-dimensional lattice structures, akin to microscopic space frames [1].

The most groundbreaking recent development in this field comes from a University of Toronto research team, which has employed multi-objective Bayesian optimization to design carbon nanolattices with an exceptional specific strength of 2.03 MPa m³ kg⁻¹ at densities below 215 kg m⁻³ [2] [3]. This achievement translates to materials possessing the compressive strength of carbon steel (180–360 MPa) while maintaining the density of expanded polystyrene (125–215 kg m⁻³) [2]. Such properties redefine the potential for lightweighting in applications from aerospace to biomedical devices, offering a pathway to substantial energy savings through reduced mass without compromising structural integrity.

Quantitative Performance Data

The mechanical performance of optimized carbon nanolattices places them in a distinct regime of the material property space. The table below summarizes key quantitative data extracted from recent studies for easy comparison.

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Optimized Carbon Nanolattices

| Property | Value | Context & Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Strength | 2.03 MPa m³ kg⁻¹ | Ultra-high value at densities < 215 kg m⁻³ [2] [3] |

| Compressive Strength | 180 - 360 MPa | Comparable to carbon steel [2] [3] |

| Density | 125 - 215 kg m⁻³ | Similar to expanded polystyrene (Styrofoam) [2] [3] |

| Young's Modulus | 2.0 - 3.5 GPa | Comparable to soft woods [3] |

| Strength Increase | Up to 118% | Versus traditional nanoarchitected designs [2] [3] |

| Stiffness Increase | Up to 68% | Versus traditional nanoarchitected designs [2] [3] |

| Strut Diameter | 300 - 600 nm | Critical for size-dependent strengthening effects [3] |

Table 2: Fabrication and Processing Parameters

| Parameter | Specification | Function and Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Pyrolysis Temperature | 900 °C | Converts polymer template to glassy, aromatic carbon [2] [3] [4] |

| Carbon Purity (sp²) | 94% | Minimized oxygen content; enhanced structural integrity [2] |

| Printing Technology | Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) | Enables nanoscale resolution for intricate 3D designs [2] [3] |

| Scalability | 18.75 million unit cells | Demonstrated via multi-focus 2PP, addressing production scale [2] |

Experimental Protocols

The fabrication of high-strength carbon nanolattices is a multi-step process that integrates computational design with advanced nanofabrication and material processing.

Protocol: Bayesian Optimization of Lattice Geometry

Objective: To computationally generate lattice geometries that maximize specific stiffness and strength while minimizing stress concentrations.

Procedure:

- Initialization: An initial lattice structure is deconstructed into its constituent beam segments.

- Parameterization: The geometry of each strut is defined by four randomly distributed control points within the design space. A continuous profile is formed using a Bézier curve, which is then revolved in 3D to create the solid strut geometry [3].

- Finite Element Analysis (FEA): Generate a high-quality training dataset by evaluating the relative density ((ρ¯"), effective Young's modulus ((E¯"), and effective shear modulus ((μ¯") for 400 randomly generated geometries using FEA [3].

- Multi-objective Bayesian Optimization (MBO): A Bayesian optimization algorithm iteratively expands a 3D hypervolume defined by the normalized mechanical properties (0 < (E¯), (μ¯) < 1) and minimized density. This process identifies the Pareto optimum surface, representing the best possible trade-offs between the objectives, typically over about 100 iterations [3] [5].

- Design Selection: From the optimized designs on the Pareto front, select structures that maximize the function ([Eρ¯·μρ¯]^{0.5}) to create unit cells robust under multimodal loading conditions [3].

Protocol: Two-Photon Polymerization and Pyrolysis

Objective: To fabricate and convert the optimized digital designs into high-purity carbon nanostructures.

Procedure:

- 3D Printing: Fabricate the optimized lattice structures using a Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) nanoscale additive manufacturing system. The process uses a photoresist (e.g., IP-Dip) to create a polymeric template of the design [3] [4]. High-speed galvo-mode printing can be employed for increased throughput [4].

- Post-Processing: Clean the printed polymer structure to remove residual resin.

- Pyrolysis: Place the polymer template in a tube furnace under an inert atmosphere or vacuum. Heat the sample to a temperature of 900 °C [2] [4]. This thermal decomposition process converts the crosslinked polymer into a glassy, aromatic carbon structure, simultaneously shrinking it to approximately 20% of its original size and significantly enhancing its mechanical properties [3].

- Characterization: Perform structural characterization using techniques like Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) to verify geometric fidelity. Mechanical properties are determined via nanoscale uniaxial compression tests to measure Young's modulus and compressive strength [3].

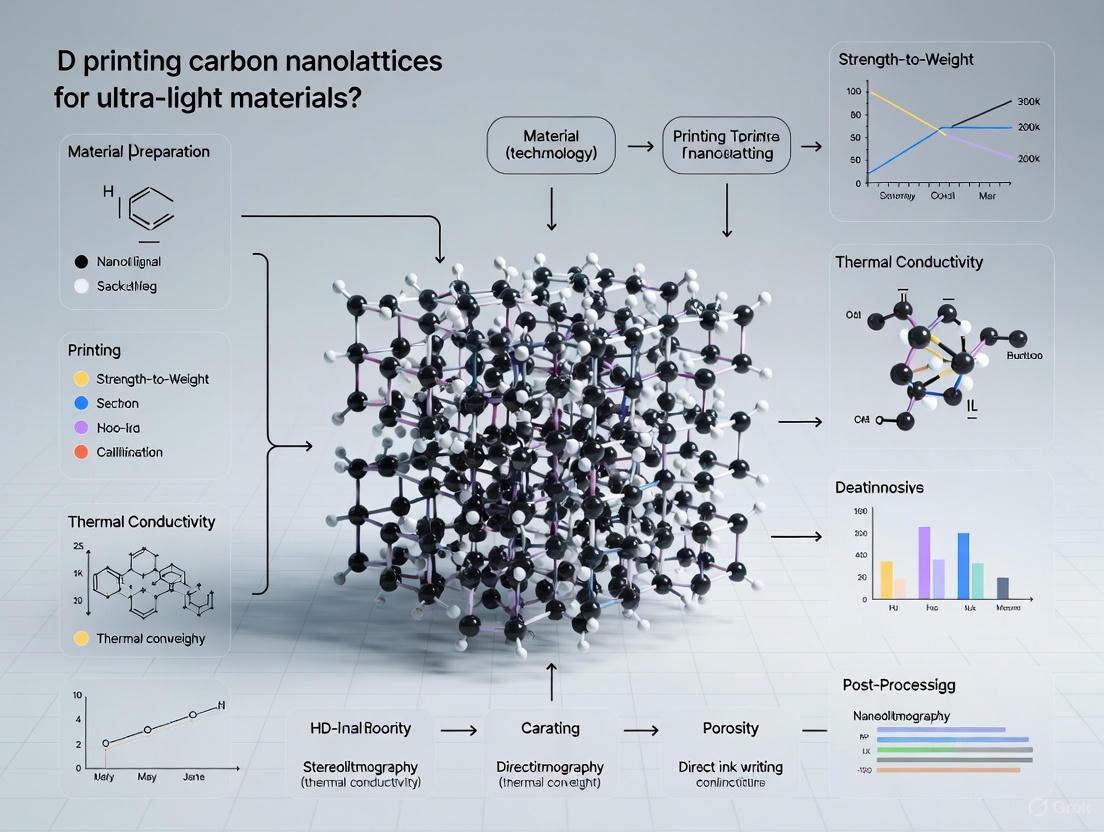

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow, from computational design to final material testing:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research and development in carbon nanolattices require a specific set of materials and technologies. The table below details the key components of the experimental pipeline.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

| Item | Function / Role | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Photoresist | Forms the polymer template via 2PP. | IP-Dip photoresist is a common choice for direct laser writing systems [4]. |

| Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) System | High-resolution 3D printing at the nanoscale. | Also known as Direct Laser Writing (DLW). Enables creation of complex 3D geometries with features down to ~300 nm [2] [4] [1]. |

| Tube Furnace | High-temperature processing under controlled atmosphere. | Used for the pyrolysis step; must be capable of maintaining temperatures of 900°C in vacuum or inert gas [3] [4]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | Computational design of optimal lattice geometries. | Custom code for multi-objective optimization, balancing stiffness, strength, and density [3] [5]. |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) Software | Simulates mechanical response of designed geometries. | Generates high-quality data for training the optimization algorithm [3]. |

| Pyrolytic Carbon | The constituent solid material forming the nanolattice struts. | Result of pyrolysis; a glassy, aromatic carbon with high sp²-bonded content (up to 94%) that provides exceptional strength [2] [3]. |

Application Workflow for Aerospace Lightweighting

The integration of these materials into functional components requires a structured approach from material selection to performance validation. The following diagram maps this application-oriented workflow:

Workflow Description:

- Component Identification: Select non-critical or secondary aircraft components (e.g., interior brackets, non-load-bearing panels) for initial technology demonstration, prioritizing parts where mass savings directly impact fuel efficiency [5].

- Load Case Analysis: Define all mechanical loads and boundary conditions the component must withstand during service. This data is crucial as the input for the generative design process.

- Topology Optimization & Bayesian Lattice Design: Use the load case data to drive the multi-objective Bayesian optimization protocol (detailed in Section 3.1) to generate a custom nanolattice geometry tailored to the specific application.

- Scale-Up Fabrication: Fabricate the component using high-throughput 2PP techniques, such as multi-focus printing, which has been demonstrated to produce structures containing over 18.75 million unit cells, addressing previous scalability challenges [2] [3].

- Pyrolysis & Post-Processing: Convert the polymer print into a carbon structure following the protocol in Section 3.2. Monitor for uniform shrinkage and potential defects.

- Component Integration & Performance Validation: Integrate the finished carbon nanolattice component into the larger system and perform validation testing. The projected performance metric is a potential fuel savings of 80 liters per year per kilogram of traditional material replaced, based on aircraft applications [5].

The fusion of artificial intelligence-driven generative design with advanced nanoscale additive manufacturing has unlocked a new paradigm in materials science. The protocols and data outlined in this document provide a roadmap for replicating and building upon the record-breaking specific strength of Bayesian-optimized carbon nanolattices. As efforts to scale production continue, focusing on refining pyrolysis parameters and further optimizing generative algorithms, these materials are poised to transition from laboratory marvels to transformative components in weight-sensitive industries. The ongoing research aims to push material properties closer to theoretical strength limits while expanding the accessible design space for next-generation engineering applications [2] [6].

Application Notes: Architectural Topologies and Performance in Carbon Nanolattices

Quantitative Performance of Nanolattice Architectures

The pursuit of ultra-lightweight, high-performance materials has led to significant advancements in nano-architected materials, particularly pyrolytic carbon nanolattices. The table below summarizes key quantitative data for various nanolattice topologies and materials, highlighting the relationship between architecture, density, and mechanical performance [4].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Micro/Nanoarchitected Materials

| Material and Architecture | Density (g/cm³) | Young's Modulus | Compressive Strength | Fracture Strain | Specific Strength (Strength-to-Density Ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrolytic Carbon (Octet-/Iso-truss) [4] | 0.24 - 1.0 | 0.34 - 18.6 GPa | 0.05 - 1.9 GPa | 14 - 17% | Up to 1.90 GPa⋅g⁻¹⋅cm³ |

| ML-Optimized Carbon Nanolattices [7] [8] | Information Missing | Information Missing | 2.03 MPa·m³/kg (Specific Stress) | Information Missing | ~5x higher than titanium |

| Ceramic Hollow-Tube Nanolattices [4] | 0.006 - 0.25 | 0.003 - 1.4 GPa | 0.07 - 30 MPa | Information Missing | Information Missing |

| Alumina-Coated Polymer Core Microlattices [4] | ~0.42 | ~30 MPa | Information Missing | ~4-6% | Information Missing |

| HEA-Coated Polymer Nanolattices [4] | 0.087 - 0.865 | 16 - 95 MPa | 1 - 10 MPa | >50% (Recoverable) | Information Missing |

| Glassy Carbon (Tetrahedral unit cells) [4] | ~0.35 | ~3.2 GPa | ~280 MPa | Information Missing | Information Missing |

Protocol: Fabrication of Pyrolytic Carbon Nanolattices via Two-Photon Lithography and Pyrolysis

This protocol details the methodology for creating pyrolytic carbon nanolattices with designable topologies, such as octet-truss and iso-truss, for ultra-lightweight material applications [4].

- 1. Principle: The process uses a two-step procedure involving direct laser writing (Two-Photon Lithography) to create a polymer template, followed by pyrolysis at high temperature to convert the polymer into pyrolytic carbon [4].

- 2. Applications: This method is suitable for producing 3D nanoarchitected materials for use in harsh thermomechanical environments, such as aerospace components, where a combination of low density, high strength, and flaw tolerance is required [4] [7].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item Name | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| IP-Dip Photoresist | A high-resolution photoresist used as the primary material for creating the initial 3D polymer scaffold via Two-Photon Lithography (TPL) [4]. |

| Two-Photon Polymerization 3D Printer | Enables additive manufacturing at micro and nano scales, creating complex 3D structures with feature sizes down to hundreds of nanometers [7]. |

| Pyrolysis Furnace (Vacuum) | A high-temperature furnace operating in a vacuum environment. It converts the polymer lattice into pyrolytic carbon through thermal decomposition at 900°C [4]. |

| Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | A machine learning algorithm used to design optimal lattice geometries that enhance stress distribution and improve the strength-to-weight ratio, requiring relatively small (~400 point), high-quality datasets [7]. |

- 3. Experimental Workflow:

4. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Lattice Design: Utilize a machine learning algorithm (e.g., multi-objective Bayesian optimization) to predict unit-cell geometries that maximize strength-to-weight ratio and improve stress distribution. The octet-truss (cubic anisotropy) and iso-truss (isotropic) are common starting topologies [4] [7].

- Template Fabrication (Two-Photon Lithography):

- Use a Two-Photon Lithography (TPL) system in high-speed galvo mode for direct laser writing.

- Print a 5x5x5 unit-cell microlattice from IP-Dip photoresist, creating struts with circular cross-sections of 0.8-3.0 μm diameter and unit-cell dimensions of approximately 2 μm [4].

- Pyrolysis:

- Place the polymer template in a vacuum pyrolysis furnace.

- Heat the furnace to 900°C to pyrolyze the polymer. This process converts the organic polymer into a glassy, pyrolytic carbon structure, significantly reducing its size and mass while increasing its strength [4].

- Structural Characterization:

- Use electron microscopy to verify the final architecture, beam diameters (typically 261 nm to 679 nm after pyrolysis), and to check for fabrication-induced defects [4].

- Mechanical Testing:

- Perform uniaxial compression experiments on the nanolattices to determine Young's modulus, compressive strength, and pre-failure deformability [4].

5. Data Analysis:

- Calculate the specific strength (strength-to-density ratio) and specific modulus (modulus-to-density ratio). Compare the results with existing micro/nanoarchitected materials and theoretical predictions [4].

- For ML-optimized lattices, validate the experimental performance (e.g., specific stress at failure) against the model's predictions [7].

6. Troubleshooting and Notes:

- Feature Size: The smallest characteristic size of the nanolattices should approach the resolution limits of the TPL technology to leverage the "smaller is stronger" effect [4] [7].

- Defect Tolerance: For densities higher than ~0.95 g/cm³, the nanolattices become increasingly insensitive to fabrication-induced defects, allowing them to attain nearly the theoretical strength of the constituent pyrolytic carbon [4].

- ML Data Efficiency: The Bayesian optimization algorithm can achieve significant performance improvements with a small (~400 data points), high-quality dataset from finite element analysis, reducing computational overhead [7].

Protocol: Optimization of Nanolattice Geometries Using Machine Learning

This protocol describes the integration of machine learning with computational mechanics to design and validate high-performance nanolattice geometries before fabrication [7].

- 1. Workflow for ML-Driven Design:

- 2. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Generate Initial Dataset: Create a set of varied lattice geometry parameters (e.g., beam diameter, node geometry, unit cell type) as input.

- Run Finite Element Analysis (FEA): Simulate the mechanical response (stress, strain) for each geometry in the dataset to generate high-quality performance data.

- Train ML Model: Feed the geometry-performance data pairs into a multi-objective Bayesian optimization algorithm. The algorithm learns the relationships between geometric parameters and performance metrics like stress distribution and strength-to-weight ratio.

- Predict Optimal Design: Use the trained model to predict new, high-performing lattice geometries that were not in the initial dataset.

- Experimental Validation: Fabricate and mechanically test the ML-predicted optimal designs to validate the model's accuracy and the performance improvements [7].

The pursuit of stronger, lighter, and more flaw-tolerant materials has led researchers to the nanoscale, where a profound scale effect governs material behavior. This phenomenon describes a fundamental transition in material properties and failure mechanisms as feature sizes shrink below a critical threshold, typically around 100 nanometers. At these dimensions, materials exhibit remarkable mechanical properties that defy their bulk counterparts, including exceptional strength-to-weight ratios and unprecedented resistance to cracks and flaws. This application note explores the mechanistic origins of the scale effect, with a specific focus on its application in 3D-printed carbon nanolattices for ultra-light materials research. The principles discussed are critical for researchers and scientists developing next-generation materials for applications ranging from aerospace to biomedical devices, where weight savings and structural reliability are paramount.

The core premise of the scale effect is that "smaller is stronger." As material dimensions approach the nanoscale, the probability of encountering critical stress-concentrating defects decreases significantly. Furthermore, the dominant failure mechanism shifts from flaw-mediated fracture to a more uniform, theoretical-strength-limited deformation. This transition enables the creation of materials whose performance is no longer dictated by the inherent defects introduced during manufacturing but by the intrinsic strength of the atomic bonds within their constituent materials. For drug development professionals, understanding these principles is also increasingly relevant in designing nanocarriers and porous scaffolds where mechanical integrity at small scales directly impacts functionality and drug release profiles.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Flaw Insensitivity

The "Smaller is Stronger" Effect

The foundational principle underlying the scale effect is the inverse relationship between feature size and strength. In macroscopic materials, failure typically initiates at stress concentrations around pre-existing flaws such as cracks, voids, or inclusions. According to Griffith's theory of fracture, the stress required to propagate a crack is inversely proportional to the square root of the crack length. Consequently, as the material volume and corresponding maximum flaw size decrease, the applied stress required to activate these flaw-mediated failure mechanisms increases dramatically. At the nanoscale, the available volume for statistically large flaws is simply insufficient to nucleate catastrophic fracture, forcing the material to approach its theoretical atomic bond strength.

Fractocohesive Length and Flaw Tolerance

A key metric for quantifying flaw insensitivity is the fractocohesive length (ξ), defined as the ratio of the material's fracture toughness (Kₐ) to its fracture energy (Γᵢ). This parameter establishes a critical transition length scale: when inherent flaw sizes are smaller than the fractocohesive length, the material exhibits flaw-insensitive behavior where its stretchability and strength remain virtually unaffected by defects. Research on nanocomposite eutectogels has demonstrated that engineering materials with centimeter-scale fractocohesive lengths (e.g., 1.19 cm) is achievable through strategic nanoscale design, making them exceptionally tolerant to cracks [9]. In such systems, stress is efficiently redistributed around crack tips through energy-dissipating molecular mechanisms, preventing localized stress from reaching critical propagation values.

Table 1: Key Parameters Governing Flaw Insensitivity at the Nanoscale

| Parameter | Description | Role in Flaw Insensitivity | Representative Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fractocohesive Length (ξ) | Ratio of fracture toughness to fracture energy (Kₐ/Γᵢ) | Defines the critical flaw size below which mechanical properties become flaw-insensitive | ~1.19 cm in POSS eutectogels [9] |

| Feature Size | Characteristic diameter of structural elements (e.g., beam diameter in a nanolattice) | Determines the maximum possible flaw size contained within the material volume | 100-500 nm in carbon nanolattices [7] |

| Theoretical Strength | Maximum stress a perfect, defect-free crystal can sustain | Becomes the dominant strength-limiting factor at small scales where flaws are eliminated | Approaches 130 GPa in defect-free graphene [10] |

Experimental Evidence and Property Enhancements

Enhanced Mechanical Properties in 2D Materials

The extraordinary mechanical properties achievable at the nanoscale are vividly demonstrated by two-dimensional (2D) materials. Monolayer graphene, for instance, exhibits a two-dimensional Young's modulus (E₂D) of approximately 340 N m⁻¹ and a phenomenal fracture strength of ~130 GPa, representing the highest strength-to-weight ratio known [10]. This translates to an elastic deformation capability of up to 20-25% before fracture. Other 2D materials like hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) and molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) similarly exhibit exceptional stiffness and strength at monolayer thicknesses, though typically lower than graphene. The confinement of atoms to a single plane and the elimination of through-thickness defects contribute significantly to these enhanced properties, providing a clear illustration of the scale effect in reducing flaw sensitivity.

Machine Learning-Optimized Carbon Nanolattices

Recent breakthroughs in nano-architected materials have successfully translated these principles to three-dimensional structures. Researchers have employed machine learning and nano-3D printing to design and fabricate carbon nanolattices with unprecedented performance. Using a multi-objective Bayesian optimization algorithm, teams from the University of Toronto and KAIST designed nanolattice geometries that minimized stress concentrations—a common source of failure initiation in larger-scale architectures [7] [8]. The resulting materials, composed of repeating unit cells with features measuring a few hundred nanometers, demonstrated a conflicting combination of properties: the strength of carbon steel with the density of Styrofoam. These optimized nanolattices achieved a specific strength of 2.03 MPa·m³/kg, approximately five times higher than that of titanium, showcasing the profound impact of nanoscale architectural control [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Mechanical Properties Across Material Scales

| Material / System | Elastic Modulus | Fracture Strength | Key Flaw-Related characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monolayer Graphene [10] | 340 N/m (2D); ~1000 GPa (3D) | 130 GPa | Nearly defect-free lattice; approaches theoretical strength |

| Bulk Steel (A36) | 200 GPa | 400-550 MPa | Strength highly dependent on microstructure and flaw distribution |

| ML-Optimized Carbon Nanolattice [7] [8] | Not specified | Specific strength: 2.03 MPa·m³/kg | Geometry eliminates stress concentrations; flaw-insensitive design |

| POSS-based Eutectogel [9] | Not specified | Fracture toughness: ~3934 J/m² | Large fractocohesive length (1.19 cm) enables flaw-tolerance |

Protocols for Nanoscale Material Synthesis and Characterization

Protocol 1: Fabrication of ML-Optimized Carbon Nanolattices

This protocol describes the synthesis of flaw-resistant carbon nanolattices using machine learning-guided design and nano-3D printing.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials:

- Multi-objective Bayesian Optimization Algorithm: A machine learning algorithm used to predict optimal lattice geometries that enhance stress distribution and strength-to-weight ratio [7].

- Two-Photon Polymerization (TPP) 3D Printer: An additive manufacturing system capable of printing at micro and nano scales (e.g., systems housed in facilities like the Centre for Research and Application in Fluidic Technologies - CRAFT) [7].

- Photoresist Polymer Precursor: A photocurable resin suitable for TPP, which will be pyrolyzed to form carbon.

Procedure:

- Data Generation for ML Training: Generate a high-quality dataset of approximately 400 data points using finite element analysis (FEA) simulations. These simulations should correlate various nanolattice geometries (e.g., beam curvature, node design) with simulated mechanical performance metrics, particularly stress distribution under load [7].

- Machine Learning Optimization: Input the FEA dataset into a multi-objective Bayesian optimization algorithm. The algorithm will iteratively learn the relationships between geometry and performance, predicting architectural designs that minimize stress concentrations and maximize the strength-to-weight ratio [7] [8].

- Nanolattice Fabrication via TPP: a. Transfer the topologically optimized design files to the TPP printer. b. Use the printer to selectively crosslink the photoresist precursor layer-by-layer, building the polymer nanolattice structure. c. Carefully develop the printed structure to remove unreacted resin.

- Pyrolysis (Optional): Place the polymer nanolattice in a high-temperature furnace under an inert atmosphere. Heat to a temperature sufficient to convert the polymer to glassy carbon, enhancing its mechanical strength and stability.

Validation: Mechanically characterize the final nanolattice prototypes through nanoindentation or micro-compression testing to validate that the experimental strength-to-weight ratio matches or exceeds the ML predictions [7].

Protocol 2: Synthesis of Highly Flaw-Insensitive Nanocomposite Eutectogels

This protocol outlines the creation of eutectogels with centimeter-scale fractocohesive length using a multi-crosslinkable nanofiller, suitable for flexible electronics and sensors.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials:

- Acrylo Polyhedral Oligomeric Silsesquioxane (POSS): A nano-sized, rigid molecular cage with eight double-bond groups that acts as a multi-functional crosslinker to form "chain-dense regions" [9].

- Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES): Prepared by mixing Potassium Chloride (KCl, ≥99%) and Glycerol (≥99%) in a molar ratio of 1:8. This solvent is environmentally friendly and provides high ionic conductivity [9].

- Acrylic Acid (≥99.5%): The primary monomer for polymer network formation.

- Photo-initiator (Irgacure 2959): Used to initiate UV-induced polymerization.

Procedure:

- Eutectic Solvent Preparation: Combine KCl and glycerol in a 1:8 molar ratio in a conical flask. Stir and heat the mixture at 60°C until a homogeneous, transparent liquid forms [9].

- Pre-gel Solution Preparation: To the DES, add acrylic acid monomer, acrylo POSS crosslinker, and the Irgacure 2959 photo-initiator. Stir the mixture thoroughly until all components are completely dissolved.

- UV Polymerization: Transfer the solution into a mold. Expose the mold to UV light (e.g., 365 nm wavelength) for a specified duration to initiate free-radical polymerization and form the crosslinked gel network.

- Post-processing: Carefully demold the resulting eutectogel. If necessary, rinse and swell the gel in additional DES to achieve the desired final dimensions and equilibrium.

Validation: Characterize the fractocohesive length by performing fracture tests on samples with pre-notches of controlled lengths. A fractocohesive length of ~1.19 cm is indicative of high flaw-insensitivity, where the failure strain remains constant for notch lengths below this threshold [9].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nano-Architected Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Flaw Insensitivity | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylo POSS [9] | Multi-functional nanoscale crosslinker; its rigid core and 8 bonding sites create high-energy "chain-dense regions" that blunt crack propagation. | Synthesis of flaw-insensitive eutectogels with high fracture toughness. |

| Two-Photon Polymerization Resin [7] | Photocurable polymer precursor that enables the direct 3D printing of complex nanolattice geometries predicted by machine learning models. | Fabrication of optimized carbon nanolattices. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) [9] | Green solvent medium for gel synthesis; provides anti-freezing properties and ionic conductivity, enabling applications in extreme conditions. | Forming the continuous phase in flaw-tolerant eutectogels. |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithms [7] [8] | Machine learning method that efficiently explores a vast design space with limited data to identify geometries that minimize stress concentrations. | Computational design of flaw-insensitive nanolattice architectures. |

Visualizing Concepts and Workflows

Conceptual Diagram: The Scale Effect Transition

The following DOT script visualizes the fundamental transition in failure mechanisms from the macro-scale to the nanoscale.

Diagram Title: Material Failure Mechanism Transition Across Scales

Experimental Workflow: Creating Flaw-Insensitive Nanolattices

This diagram outlines the integrated computational-experimental workflow for developing flaw-insensitive nanolattices.

Diagram Title: Workflow for ML-Driven Nano-Architected Material Development

The scale effect provides a powerful paradigm for transcending traditional property limits in materials engineering. By strategically designing materials with nanoscale feature sizes—such as the beam diameters in carbon nanolattices or the crosslinked networks in POSS eutectogels—researchers can create substances whose mechanical performance becomes insensitive to the flaws that typically weaken macroscopic objects. The integration of machine learning with advanced nano-fabrication techniques like two-photon polymerization marks a pivotal advancement, enabling the discovery and realization of optimal, flaw-resistant architectures that were previously inconceivable. As these protocols and principles are adopted and refined, they pave the way for a new class of ultra-light, ultra-strong, and highly reliable materials that will transform industries from aerospace to biomedical engineering.

The field of structural materials has undergone a revolutionary transformation, evolving from the early exploration of simple microlattice geometries to the contemporary era of artificial intelligence (AI)-designed nanostructures. This evolution represents a fundamental shift from human intuition-driven design to a computational, data-driven paradigm. Framed within the context of 3D printing carbon nanolattices for ultra-light materials research, this progression has enabled the creation of architectures that achieve previously unattainable combinations of properties—specifically, the strength of carbon steel coupled with the lightness of foam [11] [7]. These nano-architected materials, composed of repeating units at the nanoscale (where over 100 units are needed to match the thickness of a human hair), leverage the "smaller is stronger" effect and highly efficient geometries to achieve some of the highest strength-to-weight and stiffness-to-weight ratios known [7]. This application note details the quantitative milestones, provides detailed experimental protocols for modern approaches, and offers essential toolkits for researchers pursuing this groundbreaking technology.

Quantitative Evolution of Material Properties

The transition from early microlattices to today's AI-optimized nanolattices is marked by significant improvements in key performance metrics. The following tables summarize this quantitative evolution, providing a clear comparison of the property enhancements achieved through advanced design and manufacturing.

Table 1: Historical Evolution of Key Material Properties in Lightweight Architectures

| Material Era | Characteristic Density (kg/m³) | Specific Strength (MPa·m³/kg) | Key Design Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Polymer Microlattices | >100 | <0.5 | Simple geometric shapes (e.g., beams, octets) |

| Metal & Ceramic Nanolattices | 10 - 1000 | ~0.1 - 0.5 | Introduction of nanoscale size effects |

| AI-Designed Carbon Nanolattices (Current) | < 10 | ~2.03 | AI-optimized complex geometries |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of AI-Designed Nanolattices vs. Conventional Materials

| Material | Density | Specific Strength (MPa·m³/kg) | Relative Performance vs. Titanium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Styrofoam | Very Low | Negligible | - |

| Carbon Steel | High | ~0.4 (approx.) | Benchmark |

| Titanium Alloy | Medium | ~0.4 (approx.) | 1x |

| AI-Designed Carbon Nanolattice | Very Low | 2.03 | ~5x Higher |

The data in Table 2 underscores the breakthrough represented by AI-designed nanolattices. With a stress resistance of 2.03 megapascals for every cubic metre per kilogram of density, their performance is approximately five times higher than that of titanium, establishing a new benchmark for lightweight structural materials [7] [8].

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication and Testing of AI-Designed Carbon Nanolattices

Protocol 1: AI-Driven Design and Optimization of Nanolattice Geometries

Objective: To utilize a multi-objective Bayesian optimization algorithm for designing a carbon nanolattice geometry that maximizes the strength-to-weight ratio.

Materials and Equipment:

- High-performance computing workstation

- Finite Element Analysis (FEA) software (e.g., ABAQUS, ANSYS)

- Python environment with Bayesian optimization libraries (e.g., Scikit-optimize, GPyOpt)

Procedure:

- Define Design Space: Parameterize the nanolattice unit cell, defining variables such as beam diameter, node curvature, and strut length.

- Set Objectives: Configure the algorithm for multi-objective optimization, with primary goals of maximizing compressive strength and minimizing mass density.

- Initial Sampling: Generate an initial, small set of design permutations (e.g., 50-100) for FEA simulation.

- Iterative Optimization: a. Run FEA simulations on the current design set to evaluate performance metrics. b. Feed the performance data (e.g., stress distributions, failure points) back into the Bayesian optimization algorithm. c. The algorithm uses this data to probabilistically model the design space and predict the next most promising set of geometries to simulate. d. Repeat this loop for a predetermined number of iterations or until performance convergence is achieved. This method is highly data-efficient, requiring only about 400 high-quality data points to find an optimal solution, compared to the 20,000+ often needed by other algorithms [7].

- Validation: Select the top-performing AI-predicted design for physical fabrication and testing.

Protocol 2: Two-Photon Polymerization Lithography and Pyrolysis

Objective: To fabricate the AI-designed nanolattice via nanoscale 3D printing and convert it into a robust carbon structure.

Materials and Equipment:

- Photoresist (e.g., IP-L 780, IP-Dip)

- Two-photon polymerization (TPP) 3D printer

- Inert atmosphere furnace (for pyrolysis)

- Critical point dryer

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Convert the final 3D lattice design into a format compatible with the TPP printer (e.g., G-code or .STL with sliced layers).

- TPP Fabrication: a. Substrate Preparation: Clean a glass or silicon substrate and coat it with the photoresist. b. Laser Writing: Use a focused femtosecond laser to solidify the photoresist at the focal point, tracing the 3D structure of the nanolattice layer by layer. The process exploits two-photon absorption for high-resolution, sub-diffraction-limit printing [11] [7]. c. Development: After printing, submerge the structure in a developer solution (e.g., SU-8 developer) to dissolve the non-polymerized resin, leaving behind the solid, 3D polymer lattice.

- Pyrolysis: a. Place the developed polymer lattice into a tube furnace. b. Ramp the temperature to 900-1000°C under a continuous flow of inert gas (e.g., Argon or Nitrogen). c. Hold at the peak temperature for 1-2 hours. This process pyrolyzes the polymer, converting it into a glassy carbon structure, which significantly enhances its mechanical strength and stability [7].

- Post-processing: Use a critical point dryer to remove any residual solvents without inducing capillary forces that could collapse the delicate nanostructure.

Protocol 3: Mechanical Characterization of Nanolattices

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the compressive strength and stiffness of the fabricated carbon nanolattice.

Materials and Equipment:

- Nanoindentation system with a flat punch tip

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

Procedure:

- Sample Mounting: Secure the pyrolyzed nanolattice sample on the stage of the nanoindenter.

- Compression Test: a. Align a flat punch diamond tip (larger than the unit cell) with the top surface of the nanolattice. b. Program the nanoindenter to apply a controlled displacement or force ramp. c. Record the full force-displacement curve until the sample fractures or densifies.

- Data Analysis: a. Calculate the compressive strength from the maximum load sustained before a sharp drop in the force-displacement curve. b. Determine the effective stiffness from the slope of the initial linear-elastic region of the curve. c. Normalize the strength and stiffness by the material's density to obtain specific strength and specific stiffness.

- Structural Analysis: Use SEM imaging pre- and post-compression to observe the deformation mechanics and failure mode (e.g., buckling of struts, node fracture), correlating the mechanical performance with the AI-predicted structural behavior.

Visualization of Workflows

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core workflows and logical relationships in the development of AI-designed nanostructures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the key materials, software, and equipment essential for research in 3D printed carbon nanolattices.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Carbon Nanolattice Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| IP-L 780 Photoresist | A negative-tone photoresist for high-resolution TPP lithography. | Forms the polymer precursor structure that is later converted to carbon via pyrolysis [7]. |

| Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | A machine learning method for navigating complex design spaces with competing goals. | Core AI engine for discovering non-intuitive, high-performance nanolattice geometries without exhaustive simulation [11] [7]. |

| Two-Photon Polymerization (TPP) System | A nanoscale 3D printing technology using a femtosecond laser. | Enables the fabrication of complex, 3D AI-designed nanostructures with features down to ~100 nm [11] [7] [8]. |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) Software | Simulates mechanical stress and deformation under load. | Generates high-quality data for training the AI model and validating design predictions [7]. |

| Nanoindentation System | Measures mechanical properties at the micro/nanoscale. | Critical for experimentally validating the compressive strength and stiffness of fabricated nanolattices [7]. |

Blueprint at the Nanoscale: Fabrication Techniques and Emerging Biomedical Applications

Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) has emerged as a premier additive manufacturing technology for producing complex three-dimensional micro- and nanostructures with unparalleled precision. This technology enables fabrication of architectures with critical dimensions below the optical diffraction limit, achieving feature sizes under 100 nanometers [12] [13]. For researchers focused on developing ultra-light carbon nanolattices, 2PP offers a unique combination of nanoscale resolution and extensive 3D design freedom, facilitating the creation of mechanically optimized metamaterials that leverage the "smaller is stronger" size effect [14] [15].

The fundamental distinction of 2PP lies in its non-linear absorption process. Unlike single-photon stereolithography where polymerization occurs along the entire beam path, 2PP utilizes near-infrared femtosecond lasers to initiate polymerization only at the focal point where photon density is sufficient for simultaneous two-photon absorption [16] [12]. This confined interaction volume enables true 3D direct laser writing without layer-by-layer constraints, allowing fabrication of intricate nanolattices with exceptional mechanical properties [14].

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Physical Foundation of Two-Photon Absorption

Two-photon absorption is a non-linear optical process where a molecule simultaneously absorbs two photons to reach an excited state. The probability of this event is proportional to the square of light intensity, confining the photochemical reaction to an extremely small focal volume [12]. This non-linear relationship creates a threshold effect that enables voxel (3D pixel) sizes significantly smaller than the wavelength of light used, bypassing Abbe's diffraction limit that constrains conventional lithography techniques [13].

Comparison with Single-Photon Processes

The fundamental differences between single-photon and multi-photon processes account for 2PP's superior resolution:

Table 1: Fundamental operational differences between single-photon and two-photon polymerization processes [16] [12]

| Characteristic | Single-Photon Polymerization | Two-Photon Polymerization |

|---|---|---|

| Light Source | UV light | Near-infrared femtosecond laser |

| Absorption Mechanism | Linear along beam path | Non-linear, confined to focal point |

| Fabrication Approach | Layer-by-layer | True 3D volume writing |

| Typical Resolution | 1-50 µm | <100 nm to 1 µm |

| Design Freedom | Limited by layering artifacts | High, virtually unlimited 3D complexity |

Experimental Protocols for Carbon Nanolattice Fabrication

Pre-Fabrication Setup and Optimization

Equipment Configuration: Commercial 2PP systems such as Nanoscribe Photonic Professional GT+ or UpNano platforms typically employ a femtosecond fiber laser with wavelength centered at 780 nm, pulse length of 100-200 fs, and repetition rate of 80 MHz [13]. The selection of microscope objective determines the achievable resolution and working volume:

- High Resolution: 63×/1.40 Oil DIC objective for maximum resolution

- Balanced Approach: 25×/0.8 Imm Corr objective for medium resolution with larger working volume

- Large-Scale Structures: 20×/0.50 objective for millimeter-scale constructs with nanoscale features [13]

Parameter Optimization: Systematic parameter sweeps should be conducted to identify optimal exposure conditions for each resin system. The Nanoscribe system provides parameter scan functionality to efficiently test laser power and scanning speed combinations [17] [13]. Bayesian optimization algorithms have demonstrated exceptional efficiency in this domain, achieving optimal nanolattice designs with only approximately 400 data points compared to the 20,000+ typically required by conventional methods [14].

Carbon Nanolattice Fabrication Workflow

Step 1: CAD Model Preparation: Import 3D nanolattice designs (STL format) into printing software (e.g., DeScribe for Nanoscribe systems). Critical parameters include hatching distance (typically 100-500 nm) and slicing distance (50-200 nm) which determine the overlap between adjacent voxels [13].

Step 2: Substrate Preparation: Clean borosilicate coverslips or ITO-coated glass substrates with ethanol and deionized water, followed by oxygen plasma treatment (75 seconds) to enhance adhesion [13].

Step 3: Resin Deposition: Apply photoresist to substrate, ensuring uniform distribution without bubbles. For temperature-sensitive materials, use controlled environmental chambers (e.g., Quantum X bio with temperature regulation) [17].

Step 4: Two-Photon Polymerization: Execute printing with optimized parameters. For carbon nanolattices, typical parameters using IP-series resins with 63× objective include laser power of 15-35 mW and scan speeds of 10,000-100,000 μm/s [13].

Step 5: Development: Immerse printed structures in appropriate solvent (e.g., Propylene Glycol Monomethyl Ether Acetate for IP resins) for 20 minutes to remove non-polymerized resin, followed by rinsing in isopropanol [13].

Step 6: Pyrolysis: Convert polymer structures to carbon by heating to 900°C or higher in inert atmosphere. This process decomposes organic components, leaving pure carbon nanolattices with enhanced mechanical properties [14] [15].

Step 7: Characterization: Analyze structural integrity via scanning electron microscopy and mechanical properties through nanoindentation or compression testing [14].

Multi-Material and Functional Integration

For advanced applications, 2PP supports multi-material fabrication through sequential printing or resin exchange protocols. Recent developments enable incorporation of functional materials including hydrogels for biomedical applications [18] and conductive polymers for electronic components [17].

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials for two-photon polymerization fabrication [17] [18] [13]

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photoresists | IP-L 780, IP-P 780 (Nanoscribe) | Primary polymerizable material | Acrylate-based, high resolution, low shrinkage |

| Functional Resins | GelMA-based hydrogels, PEGDA | Bioactive structures, tissue engineering | Biocompatible, tunable mechanical properties |

| Photoinitiators | P2CK, BIS(2,4,6-TRIMETHYLBENZOYL)PHENYLPHOSPHINEOXIDE | Initiate radical polymerization upon two-photon absorption | High two-photon absorption cross-section, water-soluble options available |

| Crosslinkers | PEGDA 400 Da | Enhance mechanical strength | Increases stiffness, reduces deformation |

| Substrates | Borosilicate coverslips, ITO-coated glass | Support for fabricated structures | Optical quality, transparent for inverted systems |

| Solvents | Propylene Glycol Monomethyl Ether Acetate (PGMEA), Isopropanol | Development to remove unpolymerized resin | High purity, residue-free |

Material Properties and Selection Criteria

Photoresists for 2PP must balance processability with functional requirements. Viscosity ranges from low-viscosity fluids (~10 mPa·s) to honey-like formulations (>10,000 mPa·s) significantly impact printing resolution and feature definition [17]. For carbon nanolattice fabrication, resins with high carbon yield after pyrolysis are essential, typically achieving strength-to-weight ratios five times higher than titanium [14].

Process Optimization and Parameters

Critical Printing Parameters

Table 3: Optimized parameters for different structural requirements [14] [18] [13]

| Parameter | Typical Range | Effect on Structure | Optimization Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Power | 10-50 mW (63×) | Higher power increases voxel size, reduces resolution | Minimum power to achieve complete polymerization |

| Scan Speed | 1,000-100,000 μm/s | Slower speed increases exposure, improves mechanical properties | Balance between structural integrity and fabrication time |

| Hatching Distance | 100-500 nm | Smaller distance improves mechanical strength but increases print time | 50-70% of voxel diameter for continuous structures |

| Slicing Distance | 50-300 nm | Smaller values improve Z-resolution but increase fabrication time | Adjust based on structural requirements and aspect ratio |

| Layer Delay | 0-100 ms | Prevents overheating in dense structures | Essential for high-aspect-ratio features |

| Pulse Energy | Dependent on specific system | Directly controls polymerization threshold | Optimize for each resin system |

Bayesian Optimization for Nanolattice Design

Recent breakthroughs demonstrate machine learning approaches for designing ultra-efficient nanolattice geometries. Multi-objective Bayesian optimization algorithms can simultaneously maximize stiffness, strength, and minimize weight while requiring only approximately 400 data points compared to conventional methods needing 20,000+ simulations [14] [15]. This approach has produced carbon nanolattices with specific strength of 2.03 MPa·m³/kg, combining steel-like strength with styrofoam-like density [14].

Applications in Ultra-Light Materials Research

Carbon Nanolattices for Weight-Critical Applications

The integration of 2PP with pyrolysis enables fabrication of nano-architected materials with exceptional strength-to-weight ratios. These structures leverage size-dependent mechanical properties, becoming stronger as feature sizes decrease to nanoscale dimensions [14]. Potential applications include:

- Aerospace Components: Fuel savings of approximately 80 liters per year for every kilogram of titanium replaced [14]

- Microfluidic Devices: Complex channel architectures with sub-micron features

- Biomedical Implants: Scaffolds with tailored mechanical properties matching natural tissues

- Advanced Sensors: High-surface-area structures for enhanced sensitivity

Scaling Approaches for Macroscopic Applications

While 2PP traditionally produces microscopic structures, recent advances in multi-focus 2PP technology enable fabrication of millimeter-scale structures while maintaining nanoscale precision [15]. This breakthrough addresses a critical limitation in nano-architected materials, potentially enabling practical applications in macroscopic systems.

Troubleshooting and Technical Challenges

Common fabrication issues include structural collapse due to insufficient mechanical strength during development, incomplete polymerization from suboptimal exposure parameters, and adhesion failure between structure and substrate. Mitigation strategies include:

- Structural Collapse: Increase crosslinker concentration (e.g., 5% PEGDA), reduce development time, or implement critical point drying [18]

- Incomplete Polymerization: Conduct systematic parameter sweeps to identify optimal laser power and scan speed combinations [17] [13]

- Adhesion Failure: Implement oxygen plasma treatment for substrate activation prior to printing [13]

Post-processing techniques including additional UV curing and thermal annealing can improve mechanical properties by increasing crosslinking density [13]. For carbon nanolattices, controlled pyrolysis parameters are essential to prevent structural deformation while achieving desired material properties.

The transformation of polymer skeletons into glassy carbon through pyrolysis is a cornerstone manufacturing technique in the development of advanced nano-architected materials. This process, fundamentally known as polymer-to-carbon conversion (PolyCar), involves the thermochemical decomposition of organic polymers in an oxygen-free environment at high temperatures (typically ≥ 900 °C), resulting in a carbon material composed of a three-dimensional network of graphene fragments [19] [20]. Glassy carbon is classified as a non-graphitizing carbon, meaning it cannot be converted into crystalline graphite even at extreme temperatures, which distinguishes it from other carbon forms and is directly responsible for its unique combination of properties [19] [21]. Within the context of advanced materials research, this conversion pathway has enabled the fabrication of ultra-strong, lightweight mechanical metamaterials—particularly carbon nanolattices—that combine the strength of carbon steel with the density of Styrofoam [8] [7].

The relevance of glassy carbon to modern materials science stems from its exceptional physicochemical portfolio: high thermal stability, significant mechanical strength relative to its weight, chemical inertness, and electrical conductivity [19] [20]. When engineered into nanolattices, these properties are dramatically enhanced by size-dependent strengthening effects, allowing these architectures to achieve remarkable strength-to-weight ratios that surpass most known bulk materials [22]. For researchers focused on ultra-light materials, the precision offered by combining two-photon polymerization (2PP) 3D printing with subsequent pyrolysis provides an unparalleled method for creating deterministic, high-performance micro- and nano-architected materials.

Material Properties and Performance Data

The transformation from polymer to glassy carbon induces profound changes in the material's physical and mechanical properties. The following table summarizes the key property evolution and performance metrics of glassy carbon, particularly when structured as nanolattices.

Table 1: Properties of Polymer-Derived Glassy Carbon and Carbon Nanolattices

| Property | Pre-Pyrolysis Polymer (SU-8) | Bulk Glassy Carbon | Glassy Carbon Nanolattices | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density | ~1.2 g/cm³ [19] | ~1.4–1.5 g/cm³ [19] | 0.3–0.6 g/cm³ [22] | Well below density of water |

| Strength (Ultimate) | < 100 MPa [22] | < 100 MPa [22] | 300–3000 MPa [22] | Size-dependent strengthening |

| Young's Modulus | ~ 2–5 GPa (est. for crosslinked polymer) | Up to 1/10 of its Young's modulus [22] | Theoretical strength approached | |

| Specific Strength | Low | Moderate | 2.03 MPa m³ kg⁻¹ [2] [7] | ~5x higher than titanium |

| Structural Shrinkage | N/A | N/A | ~80% volumetric [22] | Isotropic during pyrolysis |

| Carbon Content (sp²) | N/A | High | 94% (after pyrolysis) [2] | Minimized oxygen content |

The data reveals a fundamental principle of nano-architected materials: scaling down structural elements to the nanoscale leads to exceptional mechanical properties. The specific strength of 2.03 MPa m³ kg⁻¹ highlights a material that is both ultra-light and ultra-strong, a combination that is paramount for aerospace applications where every kilogram of weight saved can lead to significant fuel reductions [7]. Furthermore, the pyrolysis process itself enhances the material by increasing the proportion of strong sp²-bonded carbon while minimizing oxygen content, leading to improved structural integrity [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Glassy Carbon Nanolattices via Two-Photon Polymerization and Pyrolysis

This protocol details the synthesis of high-strength carbon nanolattices, from the initial digital design to the final pyrolyzed structure, integrating machine learning optimization for superior performance [8] [2] [7].

1. Computational Design and Optimization:

- Objective: Design a nanolattice unit cell that minimizes stress concentrations at the nodes, a common failure point in traditional designs.

- Method: Employ a Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MBO) algorithm.

- Procedure:

- Define the optimization goals: maximize strength-to-weight ratio and improve stress distribution.

- Generate an initial dataset of approximately 400 high-quality data points using finite element analysis (FEA) simulations of various lattice geometries.

- Allow the MBO algorithm to learn from the simulations and predict optimal beam geometries and nodal connections.

- The final output is a 3D model file of the optimized nanolattice.

2. Precursor Patterning via Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP):

- Objective: Fabricate a polymer scaffold that is a precise, scaled-up replica of the optimized design.

- Materials:

- Photosensitive Resist: A thermosetting polymer resin (e.g., SU-8, a phenol-formaldehyde resin) [19].

- Substrate: A suitable wafer (e.g., silicon).

- Equipment: A two-photon polymerization 3D printer (e.g., Nanoscribe).

- Procedure:

- Spin-coat the photoresist onto the substrate to form a uniform film.

- Use the 3D printer to selectively harden the resist with a laser according to the digital design, building the structure layer-by-layer.

- Develop the printed structure in an appropriate solvent to remove the non-exposed resin, revealing the 3D polymer nanolattice.

3. Pyrolysis Conversion:

- Objective: Convert the polymer scaffold into a glassy carbon structure.

- Equipment: Tube furnace capable of maintaining a controlled inert atmosphere (Argon or Nitrogen) and temperatures up to 900°C–1200°C.

- Procedure:

- Place the polymer structure inside the furnace.

- Purge the furnace chamber with an inert gas for at least 30 minutes to eliminate oxygen.

- Initiate a programmed temperature ramp:

- Heat to 500–700°C to form the carbonaceous backbone and release heteroatoms (as CO₂, CO, CH₄) [19] [21].

- Continue heating to the target pyrolysis temperature of 900°C [2] or 1200°C [21]. Hold for 1-2 hours to allow for annealing of defects and growth of graphene crystallites.

- Cool down gradually to room temperature under an inert atmosphere.

- Critical Observations:

Protocol 2: In Situ TEM Analysis of the Pyrolysis Mechanism

This protocol, based on the work of Sharma et al., allows for the direct visualization of microstructural evolution during pyrolysis, providing critical insights for process optimization [21].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Objective: Create an electron-transparent polymer sample on a MEMS-based heating chip.

- Materials: SU-8 photoresist; MEMS heating chip with electron-transparent windows.

- Procedure:

- Directly pattern SU-8 nanostructures (e.g., nanofibers, cantilevers) onto the MEMS chip using standard lithography or spin-coating followed by etching.

2. In Situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM):

- Objective: Observe real-time structural changes during controlled heating.

- Equipment: Transmission Electron Microscope equipped with a low-voltage (80 kV) source and a MEMS heater holder.

- Procedure:

- Insert the prepared MEMS chip into the TEM holder.

- With the electron beam activated at 80 kV (to minimize knock-on damage to carbon atoms), begin the heating protocol.

- Record high-resolution TEM (HR-TEM) images and video while ramping the temperature from room temperature to 1200°C, capturing the dynamic evolution of the carbon nanostructure.

3. Data Analysis:

- Objective: Correlate observed microstructures with existing models (ribbon vs. fullerene-related).

- Procedure:

- Analyze the sequential images for the formation and collapse of intermediate structures, curvature of graphene fragments, and void formation.

- The in-situ data allows for distinguishing between two-dimensional projections and three-dimensional structures, confirming a complex 3D network of randomly shaped and sized graphene fragments [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Glassy Carbon Nanolattice Fabrication

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| SU-8 Photoresist | Primary polymer precursor for patterning. | Phenol-formaldehyde resin; thermosetting; high char yield upon pyrolysis [19]. |

| Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) Printer | High-resolution 3D printing of polymer scaffolds. | Enables direct lithography of complex 3D structures with features down to ~200 nm [7] [22]. |

| Tube Furnace | High-temperature pyrolysis reactor. | Must sustain ≤ 1200°C with precise programmable control and inert gas (N₂/Ar) atmosphere [19]. |

| Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MBO) Algorithm | Computational design of optimal lattice geometries. | Efficiently explores design space with minimal data (~400 points); predicts shapes that minimize stress concentrations [8] [7]. |

| MEMS-based Heating Chips | Substrate for in situ TEM analysis of pyrolysis. | Allows direct heating of samples within TEM chamber; enables real-time visualization of microstructural evolution [21]. |

Workflow and Structural Evolution Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for fabricating and analyzing glassy carbon nanolattices, from computational design to material characterization.

Diagram 1: Integrated Workflow for Fabrication and Analysis

The molecular and microstructural transformation during pyrolysis is a complex process, as visualized in the following diagram of the key stages from polymer to glassy carbon.

Diagram 2: Structural Evolution During Pyrolysis

The pyrolysis process is a transformative method for creating high-strength glassy carbon from polymer templates. The integration of advanced manufacturing techniques like two-photon polymerization with machine learning design and precise thermal processing has unlocked the potential to create nano-architected materials with unparalleled strength-to-weight ratios. The future of this field lies in scaling up these nanoscale designs into macroscale components and exploring multifunctional applications that leverage not only the mechanical properties but also the electrical and thermal characteristics of glassy carbon [7] [22]. For researchers in aerospace, defense, and biomedical devices, mastering this conversion process is key to developing the next generation of ultra-light, high-performance materials.

Carbon nanolattices are an emerging class of nanoarchitected materials that combine structural efficiency, exceptional mechanical properties, and nanoscale bio-functionality. This protocol details the application of machine learning (ML)-optimized carbon nanolattices in tissue engineering, with a specific focus on bone regeneration. The following Application Note provides a structured framework for the design, fabrication, and in vitro biological validation of these ultra-light, high-strength metamaterials, presenting quantitative performance data and step-by-step experimental methodologies.

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Carbon Nanolattices vs. Biological and Conventional Materials

| Material | Density (kg m⁻³) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Specific Strength (MPa m³ kg⁻¹) | Reference/Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML-Optimized Carbon Nanolattice (CFCC MBO-3) | 180 | 180-360 | 2.0-3.5 | 2.03 | [23] [3] |

| Human Cortical Bone | 1700-2000 | 130-180 | 12-18 | ~0.09 | [24] |

| Carbon Steel | ~7800 | 180-360 | 200-210 | ~0.05 | [23] |

| Styrofoam | 125-215 | <1 | Negligible | Negligible | [23] |

| Titanium Alloy (Ti-6Al-4V) | ~4400 | ~1000 | 110-120 | ~0.23 | Common Knowledge |

| Methacrylated Gelatin Hydrogel | ~1000 | ~0.0005 | 0.0001-0.0005 | Negligible | [25] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Generative Design of Carbon Nanolattices via Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization

Principle: Utilize a machine learning algorithm to design nanolattice unit cells that maximize specific stiffness and strength while minimizing density, overcoming the stress concentrations found in conventional uniform strut designs [23] [3].

Materials & Software:

- High-performance computing workstation

- Finite Element Analysis (FEA) software (e.g., Abaqus, COMSOL)

- Custom Python script for Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MBO)

Procedure:

- Define Design Space: Parameterize a cubic-face centered cubic (CFCC) lattice unit cell. Define the strut length and allow four control points to vary, enabling the generation of complex, curved beam profiles via Bézier curves [3].

- Generate Initial Dataset: Create 400 random lattice geometries within the defined design space. For each geometry, run FEA simulations to calculate three key outputs:

- Relative density (( \bar{\rho} ))

- Effective Young's Modulus (( \bar{E} ))

- Effective Shear Modulus (( \bar{\mu} )) [3]

- Iterative Optimization: The MBO algorithm iteratively explores the design space over approximately 100 cycles. It uses the acquired data to build a probabilistic model, predicting and testing new geometries that are most likely to expand the Pareto front—the set of optimal trade-offs between the three objectives [3].

- Select Optimal Design: From the final Pareto-optimal set, select a design that maximizes the composite objective ( [\frac{\bar{E}}{\bar{\rho}} \cdot \frac{\bar{\mu}}{\bar{\rho}}]^{0.5} ) for multi-modal loading resistance. The final output is a 3D model of the optimized unit cell [3].

Protocol: Fabrication of Carbon Nanolattices via Two-Photon Polymerization & Pyrolysis

Principle: Translate the digitally optimized design into a physical, high-strength carbon structure using nanoscale 3D printing and a high-temperature conversion process [23] [3].

Materials:

- Photoresist (e.g., Acrylic-based IP-L 780)

- Two-photon polymerization (2PP) system (e.g., Nanoscribe)

- Inert atmosphere tube furnace

- Nitrogen gas

Procedure:

- 3D Printing: Load the photoresist onto a silica substrate. Using the 2PP system, pattern the 3D model into a 5x5x5 lattice array, polymerizing the photoresist point-by-point to create a polymeric nanolattice [3].

- Pyrolysis: Transfer the printed polymeric structure to a tube furnace. Under a continuous nitrogen flow, heat the furnace to 900°C using a controlled ramp rate (e.g., 5-10°C/min). Maintain the peak temperature for 1 hour.

- Cooling and Harvesting: Allow the furnace to cool to room temperature under nitrogen. The resulting structure is a pyrolytic carbon nanolattice, which has shrunk to approximately 20% of its original size and possesses a glassy carbon atomic structure dominated by sp² bonds [3].

Protocol: In Vitro Biocompatibility and Osteogenic Potential Assessment

Principle: Evaluate the suitability of the carbon nanolattice as a scaffold for bone tissue engineering by assessing cell viability, attachment, and differentiation [25] [26].

Materials:

- Carbon nanolattice scaffolds

- Human Bone Marrow-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BM-MSCs)

- Standard cell culture equipment and reagents

- Live/Dead assay kit (e.g., Calcein AM / Ethidium homodimer-1)

- Materials for Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) activity assay and osteogenic gene expression analysis (qPCR)

Procedure:

- Sterilization: Sterilize carbon nanolattice scaffolds using UV light or ethanol vapor.

- Cell Seeding: Seed BM-MSCs onto the scaffolds at a density of 50,000 cells/cm². Maintain cells in osteogenic media (containing β-glycerophosphate, ascorbic acid, and dexamethasone).

- Live/Dead Assay (Day 3):

- Incubate cell-scaffold constructs with Calcein AM (2 µM) and Ethidium homodimer-1 (4 µM) for 30-45 minutes.

- Image using a confocal microscope. Live cells fluoresce green, dead cells fluoresce red [25].

- Cell Morphology Analysis (Day 3):

- Fix samples with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stain actin cytoskeleton with Phalloidin (e.g., red fluorescence) and nuclei with DAPI.

- Image using fluorescence microscopy to assess cell spreading and integration within the nanolattice [25].

- Osteogenic Differentiation (Day 7-14):

- ALP Activity: Lyse cells and quantify ALP activity using a colorimetric pNPP assay, normalized to total protein content. Elevated ALP is an early marker of osteogenesis [26].

- Gene Expression (qPCR): Extract RNA, synthesize cDNA, and perform qPCR to measure the expression of osteogenic markers (e.g., RUNX2, COL1A1, OCN) relative to housekeeping genes [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Carbon Nanolattice Research

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| IP-L 780 Photoresist | A high-resolution acrylic-based photoresist for creating the polymeric precursor structure via Two-Photon Polymerization. | Nanoscribe IP-L 780 [3] |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | A biocompatible photoinitiator used in light-induced 3D printing of hydrogels and potentially in polymer blends for nanolattices. | Sigma-Aldrich 900889 [25] |

| Methacrylic Anhydride | Used to functionalize natural biopolymers (e.g., gelatin, alginate, chitosan) with methacrylate groups, making them photo-crosslinkable. | Sigma-Aldrich 276685 [25] |

| Methacrylated Gelatin (GelMA) | A widely used, cell-adhesive bioink for creating biomimetic hydrogel coatings or composite scaffolds with carbon nanolattices. | Synthesized in-lab from gelatin and methacrylic anhydride [25] |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | Custom ML code for the generative design of high-performance lattice geometries, minimizing the need for extensive experimental trials. | Python with libraries like Scikit-optimize [23] [3] |

| Human BM-MSCs | Primary human cells used to evaluate the osteo-compatibility and bone-regenerative potential of the fabricated scaffolds. | Commercially available from providers like Lonza [25] [26] |

Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

ML-Optimized Carbon Nanolattice Fabrication & Testing Workflow

Proposed Signaling Pathway for Osteogenesis on CNTs

Nano-architected materials represent a groundbreaking class of materials engineered with precise structural features at the nanoscale. These materials combine high-performance architectures with the "smaller is stronger" effect at nanoscale sizes to achieve exceptional strength-to-weight and stiffness-to-weight ratios [7]. Recent advances have demonstrated the creation of carbon nanolattices that possess the strength of carbon steel with the density of Styrofoam, achieved through the innovative combination of machine learning and nano-scale 3D printing [8] [27]. In drug delivery, these materials offer revolutionary potential for creating ultra-light, high-precision systems that can transform controlled release applications across multiple therapeutic areas.

The integration of nano-architected materials into drug delivery systems addresses several critical limitations of conventional approaches, including poor bioavailability, systemic toxicity, and inability to target specific tissues [28]. By leveraging the tunable porosity, high surface area-to-volume ratio, and exceptional mechanical properties of carbon nanolattices, researchers can develop advanced delivery platforms that provide unprecedented control over drug release kinetics, targeting accuracy, and therapeutic efficacy.

Fundamental Properties and Quantitative Performance Data

Key Characteristics of Carbon Nanolattices

Carbon nanolattices are composed of tiny building blocks or repeating units measuring a few hundred nanometers in size—it would take more than 100 of them patterned in a row to reach the thickness of a human hair [7]. These building blocks, composed of carbon, are arranged in complex 3D structures that can be optimized for specific mechanical and functional properties. The machine learning-optimized geometries overcome the stress concentration limitations of traditional lattice shapes with sharp intersections and corners, which led to early local failure and breakage [7].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Nano-Architected Materials Compared to Conventional Materials

| Material | Density | Specific Strength (MPa·m³/kg) | Relative Performance | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML-Optimized Carbon Nanolattice | Styrofoam-equivalent | 2.03 | ~5x higher than titanium | Aerospace components, lightweight medical implants, micro-drug reservoirs |

| Titanium | 4.51 g/cm³ | ~0.4 (reference) | Baseline | Orthopedic implants, aerospace structures |

| Carbon Steel | 7.8 g/cm³ | ~0.25 (estimated) | ~50% of titanium | Structural components, machinery |

| Standard Polymer | 1.0-1.4 g/cm³ | 0.01-0.05 | ~2-10% of titanium | Conventional drug delivery systems, medical devices |

Table 2: Drug Loading and Release Performance of Nano-Architected Systems

| Parameter | Nano-Architected System | Conventional Nanoparticles | Polymeric Hydrogels | Significance for Drug Delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Area-to-Volume Ratio | Extremely high (>1000 m²/g) | High (100-500 m²/g) | Moderate (10-100 m²/g) | Enhanced drug loading capacity |

| Pore Size Control | 1-100 nm (precise tunability) | 5-50 nm (limited control) | 10-1000 nm (broad distribution) | Precise control over drug release kinetics |

| Mechanical Strength | Exceptional (2.03 MPa·m³/kg) | Moderate to low | Variable (soft materials) | Structural integrity in physiological environments |

| Degradation Tunability | Programmable via architecture | Chemistry-dependent | Polymer chemistry-dependent | Controlled release profiles and clearance |

The optimized nanolattices more than doubled the strength of existing designs, withstanding a stress of 2.03 megapascals for every cubic metre per kilogram of its density [7] [27]. This exceptional strength-to-weight ratio enables the creation of robust yet ultra-lightweight drug delivery systems that maintain structural integrity under physiological conditions while minimizing the overall implant mass.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Machine Learning-Driven Design of Optimized Nanolattices for Drug Delivery

Objective: To design carbon nanolattices with optimized geometries for enhanced mechanical properties and drug loading capacity using machine learning algorithms.

Materials and Equipment:

- High-performance computing workstation with GPU acceleration

- Multi-objective Bayesian optimization algorithm software

- Finite element analysis (FEA) simulation environment

- Material property databases (elastic modulus, density, failure criteria)

Methodology:

Problem Formulation:

- Define optimization objectives: maximize strength-to-weight ratio, minimize stress concentrations, and maximize surface area for drug loading.

- Identify constraint parameters: manufacturability limits, minimum feature size (≥100 nm), and material availability.

Algorithm Implementation:

Geometry Simulation and Optimization:

- Run simulations of different geometries to identify shapes providing balanced stress distribution and optimal strength-to-weight ratio.

- Generate 18.75 million carbon nanolattice design variations for analysis [29].

- Select top-performing architectures that avoid stress concentration at connection points through reshaped geometries.

Validation and Iteration:

- Validate computational predictions through experimental testing of prototype structures.

- Refine algorithm parameters based on empirical results.

- Finalize designs achieving specific strength of 2.03 MPa·m³/kg with Styrofoam-equivalent density.

Expected Outcomes: Generation of novel nanolattice geometries with significantly improved mechanical properties and enhanced potential for drug loading applications.

Protocol 2: Fabrication of Carbon Nanolattices via Two-Photon Polymerization 3D Printing

Objective: To fabricate optimized carbon nanolattice structures using high-resolution additive manufacturing technology.

Materials and Equipment:

- Nanoscribe Photonic Professional GT2 two-photon polymerization 3D printer [27]

- Photoresist polymer precursor (compatible with carbon conversion)

- Carbonization furnace with controlled atmosphere

- Critical point dryer for post-processing

- High-resolution SEM for structural characterization

Methodology:

Pre-printing Setup:

- Calibrate the two-photon polymerization printer for nanoscale precision.

- Prepare photoresist material according to manufacturer specifications.

- Load optimized nanolattice design files (from Protocol 1) into printing software.

Printing Process:

- Initiate two-photon polymerization process with precise laser focus control.

- Construct nanolattices layer-by-layer with building blocks measuring a few hundred nanometers [7].

- Implement in-process monitoring to ensure dimensional accuracy and structural integrity.

Post-processing:

- Develop printed structures in appropriate solvent to remove unpolymerized resin.

- Apply critical point drying to prevent structural collapse during solvent removal.