Lipid Nanoparticles vs. Viral Vectors: A Strategic Guide to Gene Delivery Technologies

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of lipid nanoparticle (LNP) and viral vector platforms for gene delivery, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Lipid Nanoparticles vs. Viral Vectors: A Strategic Guide to Gene Delivery Technologies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of lipid nanoparticle (LNP) and viral vector platforms for gene delivery, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational mechanisms, current clinical applications across various diseases, strategies to overcome technical and immunological challenges, and a direct comparative analysis of safety, efficacy, and scalability. The scope extends from basic principles to advanced optimization techniques and future directions, serving as a strategic resource for selecting the appropriate delivery system for specific therapeutic goals.

Core Principles and Evolutionary Paths of Gene Delivery Systems

The success of gene therapy hinges on the efficient delivery of genetic cargo into target cells, a process facilitated by engineered vectors. These platforms are broadly categorized into viral and non-viral systems. Viral vectors, including adeno-associated virus (AAV), lentivirus (LV), and adenovirus (Ad), are engineered from naturally evolving viruses and leverage their innate ability to infect cells [1]. In contrast, non-viral vectors such as lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are synthetic constructs designed to overcome the limitations of their viral counterparts [2]. The choice between these platforms involves a critical trade-off between delivery efficiency, cargo capacity, safety profile, and manufacturability [3] [4]. Viral vectors generally offer high transduction efficiency and long-lasting gene expression, while LNPs provide a safer profile with lower immunogenicity, larger cargo capacity, and the significant advantage of being suitable for re-dosing [5]. This guide provides a objective comparison of these platforms, focusing on their mechanisms, performance data, and experimental applications for researchers and drug development professionals.

Platform Mechanisms and Workflows

Viral Vector Mechanisms

Viral vectors are modified viruses that have been rendered replication-incompetent but retain their ability to deliver genetic material into cells. Their mechanisms are distinguished by their routes of cell entry and genomic handling.

- Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV): AAV vectors bind to cell surface primary receptors (e.g., HSPG) and coreceptors prior to clathrin-mediated endocytosis. The low pH of the endosome triggers conformational changes in the viral capsid, leading to endosomal escape. The single-stranded DNA genome is then released into the nucleus, where it predominantly remains as a non-integrating episome, facilitating long-term transgene expression in non-dividing cells [1] [6].

- Lentivirus (LV): As a complex retrovirus, LV enters cells via envelope-mediated fusion, often pseudotyped with the VSV-G protein. Following entry, the viral RNA genome is reverse-transcribed into double-stranded DNA in the cytoplasm. This DNA, along with viral integrase, is imported into the nucleus and integrates into the host cell genome, enabling stable, long-term transgene expression that is passed on to daughter cells [1] [7].

- Adenovirus (Ad): Ad vectors bind to the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) and are internalized via endocytosis. The viral capsid is destabilized in the endosome, and the DNA genome is transported to the nucleus where it remains episomal. Ad vectors can efficiently transduce both dividing and non-dividing cells and typically elicit high levels of transient gene expression, but also strong immune responses [1] [6].

LNP Mechanism and Workflow

LNPs are synthetic, multi-component systems that self-assemble into nanoparticles to encapsulate and protect nucleic acids. The typical LNP formulation for mRNA delivery consists of four key lipids: an ionizable cationic lipid, a phospholipid, cholesterol, and a PEG-lipid [2] [8].

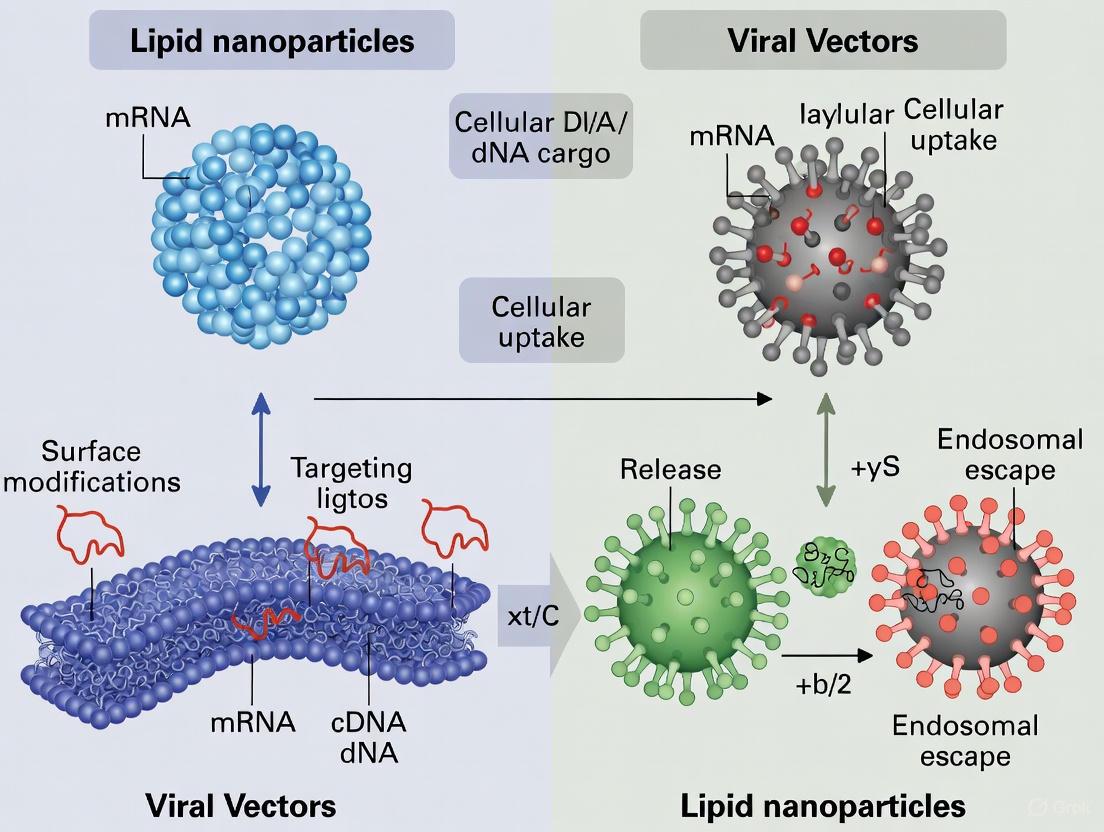

The delivery mechanism involves a sequence of critical steps, visualized in the workflow below.

Figure 1. LNP Delivery Workflow. The process begins with systemic administration. Following cellular uptake via endocytosis, the key mechanistic step is endosomal escape: the acidic environment of the endosome protonates the ionizable cationic lipids, promoting inverted hexagonal phase structure formation and fusion with the endosomal membrane, resulting in cytoplasmic release of the nucleic acid payload [2] [6]. The mRNA is then translated into the therapeutic protein, resulting in transient expression.

Comparative Performance Data

The following tables summarize the key characteristics and performance metrics of AAV, Lentivirus, Adenovirus, and LNP platforms, based on current literature and clinical data.

Table 1. Comparative Overview of Gene Delivery Platforms

| Feature | AAV | Lentivirus (LV) | Adenovirus (Ad) | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payload Type | ssDNA | RNA (reverse transcribed to dsDNA) | dsDNA | mRNA, siRNA, plasmid DNA, proteins [5] |

| Cargo Capacity | <5 kb [5] [4] | ~8 kb [7] | ~8-36 kb [1] | >10 kb, versatile/unrestricted [5] [4] |

| Integration Profile | Predominantly episomal (<0.1% integrates) [1] | Integrates into host genome [1] | Episomal | Non-integrating [3] |

| Expression Duration | Long-term (months to years) [3] | Long-term (stable in dividing cells) [7] | Short-term (transient) [1] | Short-term (transient) [3] |

| Immunogenicity | Moderate; pre-existing immunity concerns [1] | Moderate; ex vivo use minimizes this [7] | High; strong inflammatory response [1] [6] | Low; suitable for re-dosing [3] [5] |

| Primary Applications | Inherited retinal diseases, SMA, hemophilia [1] [9] | Ex vivo cell therapy (CAR-T, HSPCs) [1] [7] | Vaccines, oncolytic therapy [1] [7] | mRNA vaccines, siRNA therapeutics, gene editing [3] [9] |

Table 2. Experimental and Manufacturing Considerations

| Consideration | AAV | Lentivirus (LV) | Adenovirus (Ad) | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Titer/ Potency (Typical) | High (in vivo) [3] | High (ex vivo) [3] [7] | Very High [1] | Moderate to High (cargo and cell-type dependent) [3] [2] |

| In Vivo Delivery Efficiency | High for specific tissues (e.g., liver, muscle, CNS) [3] | Developing for in vivo use [7] | High for multiple tissues [1] | High for liver; improving for extrahepatic targets [5] [4] |

| Manufacturing Complexity | High; biological production, difficult purification [4] | High; multi-plasmid transfection of cells [7] | Moderate [1] | Low; rapid, scalable synthetic process [3] [4] |

| Relative Cost of Goods (COGS) | Very High [4] | High [7] | Moderate | Low [4] |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Vivo Gene Editing with LNPs

This protocol details the use of LNPs to deliver CRISPR-Cas9 components for gene editing in mouse liver, a common application for this platform [10] [2].

- LNP Formulation: Utilize a microfluidic device to mix an ethanolic lipid solution (containing ionizable lipid, DSPC, cholesterol, and DMG-PEG2000 at a defined molar ratio) with an aqueous solution containing CRISPR-Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA at a 1:3 volumetric flow rate ratio [2].

- Dialysis and Concentration: Dialyze the formed LNP suspension against a suitable buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4) for several hours to remove ethanol and exchange the external buffer. Subsequently, concentrate the LNPs using centrifugal filter units.

- Characterization: Measure the particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential of the LNPs using dynamic light scattering. Determine encapsulation efficiency using a Ribogreen assay.

- In Vivo Administration: Administer the LNP formulation to mice via systemic tail-vein injection at a dosage of 0.5-3 mg mRNA per kg body weight. A common dose for liver editing is 1 mg/kg [10].

- Analysis: After 3-7 days, harvest target tissues (e.g., liver). Extract genomic DNA and assess editing efficiency at the target locus using next-generation sequencing (NGS) or T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) assay. Evaluate potential off-target editing at predicted sites.

Protocol: Directed Evolution of Engineered VLPs

This advanced protocol, adapted from a recent Nature Biotechnology study, uses barcoded sgRNAs to evolve engineered virus-like particles (eVLP) with improved properties, showcasing a high-throughput viral vector engineering method [10].

- Library Construction: Generate a library of eVLP production vectors, each encoding a unique capsid variant and a corresponding uniquely barcoded sgRNA.

- eVLP Production and Selection: Transfect the library into producer cells under single-variant conditions to generate a library of barcoded eVLPs. Subject this eVLP library to a selection pressure for a desired property (e.g., resistance to human serum, enhanced transduction of a specific cell type).

- Barcode Sequencing and Analysis: Transduce target cells with the post-selection eVLPs. Recover the genomic DNA from transduced cells and amplify the barcode regions by PCR. Identify enriched barcodes in the post-selection population compared to the input library via next-generation sequencing.

- Hit Validation: Re-constitute the eVLP capsid sequences corresponding to the enriched barcodes. Produce these individual eVLP hits and validate their improved performance (e.g., increased transduction efficiency, improved production titer) in secondary functional assays.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3. Essential Reagents for Gene Delivery Research

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Cationic Lipids | Core component of LNPs for nucleic acid encapsulation and endosomal escape [2] [6] | Positively charged at low pH (facilitates RNA complexation), neutral at physiological pH (reduces toxicity). Examples: DLin-MC3-DMA, SM-102. |

| PEG-Lipids | Stabilizes LNP surface; modulates pharmacokinetics and cellular tropism [2] | Prevents nanoparticle aggregation and non-specific protein adsorption. Can contribute to the "accelerated blood clearance" phenomenon upon repeated dosing [2]. |

| VSV-G Envelope Glycoprotein | Common pseudotyping protein for Lentiviral and other viral vectors [10] [7] | Confers broad tropism by binding to ubiquitous LDL receptors. Enhances vector stability and enables concentration by ultracentrifugation. |

| Polyethylenimine (PEI) | Cationic polymer for non-viral transfection, often used in research [8] | High positive charge density allows for strong DNA condensation and proton-sponge effect for endosomal escape. Can be cytotoxic. |

| Barcoded sgRNA Libraries | High-throughput screening of delivery vehicle function and evolution [10] | Allows for multiplexed tracking of vector variants in a pool. Enables directed evolution of novel capsids and selection for specific tissue tropisms. |

| GalNAc Ligands | Conjugate for targeted delivery of RNA therapeutics to hepatocytes [9] | Binds specifically to the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) on liver cells. Enables subcutaneous administration and potent, selective liver gene silencing. |

The landscape of gene delivery is diverse, with no single platform serving as a universal solution. The choice between AAV, lentivirus, adenovirus, and LNP is dictated by the specific therapeutic goal. AAV remains the gold standard for long-term gene expression in non-dividing cells, while lentivirus is indispensable for stable genetic modification in dividing cells, especially ex vivo. Adenovirus is powerful for vaccines and oncolytic therapy where transient, high-level expression is desired. LNPs have emerged as a versatile, safe, and scalable platform, particularly suited for transient applications like mRNA vaccines and gene editing, with a superior safety profile for re-dosing [3] [4] [9]. Future progress will likely involve combining the strengths of different platforms and further engineering to overcome remaining barriers, such as pre-existing immunity to viral vectors and the targeted delivery of LNPs beyond the liver [5] [7].

Gene therapy represents a transformative approach in modern medicine, aiming to treat diseases by delivering therapeutic genetic material into a patient's cells. The success of this intervention hinges entirely on the delivery vehicle, or vector, which must safely and efficiently transport its cargo to the target cells. For decades, viral vectors dominated this landscape, leveraging the innate ability of viruses to infect cells. However, the past few years have witnessed a significant shift with the rapid ascent of non-viral vectors, particularly lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), which offer a safer and more versatile alternative [9]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two technologies, tracing their historical evolution and providing a detailed, data-driven analysis of their current capabilities for researchers and drug development professionals.

A Tale of Two Technologies: Historical Progression

The Era of Viral Vectors

The use of viral vectors in gene therapy has a history dating back to the 1970s, with the first recorded death attributed to a viral vector administration occurring in 1999 [11]. The powerful natural infection mechanism of viruses made them an obvious candidate for early gene therapy research. Among the most prominent viral vectors are:

- Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs): Known for their favorable safety profile, as they are non-pathogenic and generally non-integrative. This has made them a preferred choice for many in vivo gene therapies, with about 72% of cell and gene therapy (CGT) trials using adenovirus or AAVs [11].

- Lentiviruses (LV): Widely used in ex vivo therapies, such as CAR-T cell treatments for blood cancers, because they can integrate their genetic material into the host genome, allowing for long-term gene expression [3] [12].

- Adenoviruses (Ad): Despite early setbacks, they remain relevant but are associated with stronger immune responses [11].

The first major milestones for viral vectors came with regulatory approvals. Spark Therapeutics' Luxturna (voretigene neparvovec) for an inherited retinal dystrophy was approved in 2017, followed by beti-cel for beta-thalassemia in 2022 [11]. To date, 29 viral vector-based gene therapies have gained market approval [12].

The Rise of Non-Viral LNPs

While viral vectors were advancing, research into non-viral methods persisted, seeking to overcome the limitations of immunogenicity and manufacturing complexity. The breakthrough for lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) came largely from their successful deployment in mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines, which demonstrated their efficacy and safety on a global scale [3] [13].

LNPs are tiny, spherical carriers composed of lipids that encapsulate therapeutic genetic material. Their rise signifies a move towards safer, more scalable, and more versatile delivery systems [3] [13]. The first LNP-based gene therapy, Onpattro (patisiran), was approved in 2018 for the treatment of hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis [12]. A significant recent advancement is the development of the first safe and effective DNA-loaded LNPs (DNA-LNPs), which overcome the previous fatal barrier of severe immune activation and open doors for treatments for chronic diseases [14].

Head-to-Head Comparison: Performance Data

The choice between viral vectors and LNPs is multifaceted. The following tables summarize key quantitative and qualitative differences to inform research and development strategies.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Key Performance Indicators

| Parameter | Viral Vectors (e.g., AAV, LV) | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) |

|---|---|---|

| Transfection Efficiency | High (evolved cellular entry mechanisms) [13] | Comparable and improving, especially in specific cell lines [13] |

| Duration of Expression | Long-term or permanent (e.g., AAVs: sustained; LVs: integrated) [3] | Transient (hours to days for mRNA); longer with DNA-LNPs (~6 months) [3] [14] |

| Immunogenicity | High; pre-existing immunity and immune responses limit re-dosing [3] [11] | Lower; more suitable for repeated dosing [3] [13] |

| Scalability & Manufacturing | Complex, time-consuming, costly (CAGR 21.65% for mfg. market) [15] [13] | Relatively easy to scale; commercially viable [3] [13] |

| Payload Capacity | Limited (<~5 kb for AAV) [3] | Versatile; can deliver mRNA, siRNA, DNA, CRISPR components [3] |

| Tumor Accumulation | Varies by serotype and engineering | <10% with passive targeting; up to 89% with AI-optimized active targeting [16] |

Table 2: Qualitative Comparison of Advantages and Limitations

| Aspect | Viral Vectors | Lipid Nanoparticles |

|---|---|---|

| Key Advantages | • High-efficiency transduction• Long-term gene expression• Proven clinical success (29 approved therapies) [12] | • Low immunogenicity• Large payload capacity• Re-dosing possible• Simplified manufacturing [3] [13] |

| Key Limitations & Risks | • Immune response & toxicity (e.g., liver failure) [11]• Insertional mutagenesis (mainly LV) [3]• Difficult and expensive to manufacture at scale [13] | • Transient expression (for mRNA)• Off-target delivery can cause toxicity (e.g., hepatotoxicity) [16]• Requires optimization for tissue targeting [3] |

| Ideal Use Cases | • Gene therapies requiring permanent correction (e.g., genetic disorders) [3]• Ex vivo cell engineering (e.g., CAR-T) [12] | • mRNA vaccines & short-term therapies [3]• Treatments requiring repeated dosing [3]• Systemic delivery & CRISPR gene editing [3] [13] |

Advanced Experimental Protocols in LNP Research

Protocol: ASSET for Targeted mRNA Delivery

A major challenge for LNPs is precise tissue targeting. The Antibody-Specific Targeted LNP (ASSET) system was developed to overcome the suboptimal antibody orientation from conventional conjugation chemistries like EDC/NHS, which randomly attach via lysine residues and can inactivate the antigen recognition domain [17].

Methodology:

- Nanobody Engineering: An antibody-capturing nanobody (TP1107) is engineered. Using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), the precise binding site to the Fc domain of an IgG is determined.

- Site-Specific Modification: A synthetic amino acid (p-azido-phenylalanine, azPhe) is incorporated at the identified optimal site (Gln15) in TP1107, creating TP1107optimal. This is achieved using a genomically recoded E. coli host system [17].

- Lipid Conjugation: TP1107optimal is conjugated to DSPE-PEG2000-DBCO lipid via a click chemistry reaction between the DBCO group and the azide. This creates a lipid-PEG-nanobody construct.

- LNP Functionalization: The lipid-PEG-nanobody construct is incubated with pre-formed LNPs, inserting into the LNP membrane via its DSPE anchor.

- Antibody Capture: The functionalized LNPs are incubated with the desired targeting antibody, which is captured by the surface-exposed nanobody in an optimal orientation, ready for cell-specific delivery [17].

Data & Outcome: This method resulted in protein expression levels more than 1,000 times higher than non-targeted LNPs and more than 8 times higher than conventional antibody functionalization techniques, demonstrating highly efficient in vivo T cell targeting [17].

LNP Antibody Capture System Workflow

Protocol: Overcoming STING Pathway Activation for DNA-LNPs

A long-standing barrier to DNA-LNP therapy was lethal immune activation. Research discovered that standard DNA-LNPs trigger the STING (Stimulator of Interferon Genes) pathway, a defensive mechanism that causes severe inflammation [14].

Methodology:

- Problem Identification: Researchers established that loading DNA into standard mRNA-LNP formulations was lethal to 100% of healthy mice in lab tests, confirming a critical safety barrier.

- Mechanism Investigation: The inflammatory reaction was traced to the activation of the innate immune cGAS-STING pathway by the delivered DNA.

- Solution Development: Instead of modifying the DNA nucleotides (as done for mRNA), the team focused on the LNP composition. They incorporated a natural anti-inflammatory molecule, nitro-oleic acid (NOA), into the DNA-carrying particles.

- Validation: The safety and efficacy of the NOA-modified DNA-LNPs were tested in vivo. The modified particles completely eliminated the fatal reactions, with all test mice surviving [14].

Data & Outcome: This advancement enabled treated cells to produce the intended therapeutic proteins for about six months from a single dose, a significant duration compared to the short lifespan of mRNA therapies. It also allows for larger genetic payloads and more precise targeting compared to viral methods [14].

{width=760px} DNA-LNP Safety Breakthrough Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Successful research and development in gene delivery rely on a suite of critical reagents and technologies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | Core component of LNPs; enables nucleic acid encapsulation and endosomal escape [17] [16]. | DLin-MC3-DMA (MC3), SM102 [17]. AI is used to design novel ionizable lipids with programmable pKa [16]. |

| Helper Lipids | Provide structural integrity to the LNP [17]. | DSPC, DOPE, Cholesterol [17]. |

| PEGylated Lipids | Enhance particle stability and circulation time; can influence targeting [17]. | DMG-PEG2000 (shorter C14 chain), DSPE-PEG2000 (longer C18 chain) [17]. PEG-lipids are also used for conjugating targeting ligands. |

| Targeting Ligands | Enable active targeting to specific cell types by binding to surface receptors. | Antibodies, nanobodies (e.g., TP1107 [17]), or small molecules (e.g., GalNAc for hepatocytes [12]). |

| Viral Vectors (AAV, LV) | Gold standard for high-efficiency gene delivery and long-term expression in gene therapy research. | AAV serotypes (e.g., AAV8, AAVrh74) for in vivo delivery; Lentivirus for ex vivo cell modification (e.g., CAR-T) [11] [12]. |

| AI/ML Platforms | Accelerate LNP design by predicting structure-property relationships and optimizing formulations virtually. | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for virtual screening; Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) for de novo lipid design [16]. |

The field of gene delivery is rapidly evolving beyond a simple competition between viral and non-viral vectors. Future directions point toward hybrid approaches and intelligent design [3] [16].

- AI-Driven Optimization: Artificial intelligence is poised to revolutionize LNP development. Machine learning models can perform virtual screening of millions of lipid combinations, dramatically reducing development time from 6-12 months to a fraction of that, while also improving targeting specificity and reducing off-target effects [16].

- Combination Strategies: Researchers may leverage the strengths of both platforms—for example, using LNPs for initial or repeated dosing and viral vectors for sustained expression in specific tissues [3].

- Expanding Therapeutic Horizons: The advent of safe DNA-LNPs and advanced targeting technologies is set to broaden the application of gene therapies from rare diseases to common chronic conditions, such as heart disease and cancer [14].

In conclusion, both viral vectors and LNPs are powerful tools in the gene therapy arsenal. Viral vectors remain the established choice for therapies requiring long-term, permanent gene expression and have a robust track record of clinical success. LNPs, however, offer distinct advantages in safety, manufacturing scalability, and versatility, making them particularly suitable for vaccines, transient therapies, and treatments requiring re-dosing. The choice between them is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with the therapeutic goal, target tissue, and desired duration of effect.

In the field of gene delivery, the efficacy and safety of a therapeutic are fundamentally dictated by its delivery vehicle. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and viral capsids represent two dominant classes of delivery systems, each with a distinct structural blueprint that determines their function, capabilities, and limitations. LNPs are synthetic, spherical nanoparticles, while viral capsids are the protein shells of engineered viruses. Understanding their precise composition is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals to rationally select and optimize vectors for specific gene therapy applications. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of their structural compositions, supported by experimental data and characterization methodologies.

Core Structural Components and Their Functions

The fundamental architectures of LNPs and viral capsids arise from the assembly of their constituent parts, which directly correlate to their performance in gene delivery.

Composition of Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs)

LNPs are sophisticated synthetic assemblies typically ranging from 50 to 150 nm in diameter [18] [19]. Their formulation is a precise mixture of four key lipidic components, each playing a critical role in stability, delivery, and release.

- Ionizable Lipids: This is the most crucial functional component. These lipids are positively charged at acidic pH during formulation, enabling efficient encapsulation of negatively charged nucleic acids, but are neutral at physiological pH, reducing toxicity [19] [20]. Their protonation in the acidic environment of the endosome is key to destabilizing the endosomal membrane and facilitating the release of the genetic payload into the cytoplasm. Examples include ALC-0315 and SM-102 [18] [19].

- Phospholipids: These lipids, such as DSPC (1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), act as structural lipids that form the main bilayer structure of the nanoparticle, contributing to its stability and integrity [18] [20].

- Cholesterol: Cholesterol is a stability lipid that integrates into the LNP bilayer. It enhances structural integrity, improves packing efficiency, and facilitates membrane fusion, thereby aiding in cellular uptake and endosomal escape [18] [20].

- PEGylated Lipids: These lipids, like DMG-PEG2000, are located on the surface of the LNP. They play a dual role: they control particle size and prevent aggregation during storage and manufacturing, and they reduce nonspecific interactions in vivo by creating a hydrophilic layer [19] [20]. The PEG lipid is designed to dissociate after administration to allow cellular uptake.

The following diagram illustrates the assembly and structure of a typical LNP.

Composition of Viral Capsids

Viral vectors are engineered from viruses, with their capsids providing the natural machinery for efficient cellular entry. The specific protein composition varies by virus type, defining its tropism and behavior.

- Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Capsids: AAVs are small (~20 nm), non-enveloped viruses with an icosahedral protein capsid [1] [21]. The capsid is composed of three viral proteins (VP1, VP2, and VP3) that assemble in a specific ratio. These proteins determine the vector's tropism—its ability to infect specific tissues like liver, muscle, or neurons—and are a key target for engineering to alter targeting and evade pre-existing immune responses [21].

- Lentivirus (LV) Capsids: Lentiviruses are enveloped viruses, meaning their capsid is surrounded by a lipid bilayer derived from the host cell [1]. This envelope is studded with viral glycoproteins (e.g., VSV-G) that are essential for recognizing and entering target cells. The internal core contains the viral genome and enzymes. The ability of LVs to integrate into the host genome enables long-term gene expression but carries a risk of insertional mutagenesis [1] [21].

- Adenovirus (AdV) Capsids: Adenoviruses are larger, non-enveloped viruses with an icosahedral capsid. Their surface is characterized by fiber proteins that protrude from the vertices, which are critical for binding to host cell receptors. AdV vectors offer high transgene expression and large cargo capacity but often trigger strong immune responses [1] [21].

The schematic below generalizes the structure of an enveloped viral vector like Lentivirus.

Comparative Structural Analysis

The distinct compositions of LNPs and viral capsids translate into direct differences in their physical characteristics, payload capacity, and functional outcomes. The table below summarizes a direct, quantitative comparison based on the available experimental data.

Table 1: Direct Comparison of LNP and Viral Capsid Attributes

| Feature | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Viral Vectors (e.g., AAV, Lentivirus) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Components | Synthetic ionizable lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, PEG-lipids [19] [20] | Viral proteins (e.g., VP1-3 for AAV), sometimes a host-derived lipid envelope [1] |

| Typical Size Range | 50–150 nm [18] [19] | ~20–100 nm (varies by virus; AAV ~20 nm) [21] |

| Payload Type | mRNA, siRNA, saRNA, CRISPR-Cas9 RNA components [3] [19] | Primarily DNA; some RNA (e.g., Lentivirus) [1] |

| Payload Capacity | High. Can deliver large RNA payloads (>4.5 kb), including multiple RNAs for CRISPR [19]. | Limited. AAV cargo capacity is ~4.7 kb, restricting delivery of large genes [21]. |

| Immunogenicity | Lower. Suitable for repeat dosing, though anti-PEG immunity can occur [3] [22]. | Higher. Pre-existing and treatment-induced immunity can limit efficacy and re-dosing [3] [21]. |

| Expression Duration | Transient. Ideal for short-term expression (e.g., vaccines, transient editing) [3]. | Long-term/Stable. Can provide sustained expression; integrating vectors (LV) can be permanent [3] [1]. |

| Manufacturing | Highly scalable and rapid. Microfluidic mixing allows production in days [3] [19]. | Complex and time-consuming. Requires cell culture, takes several weeks, difficult to scale [21] [19]. |

Experimental Characterization of Composition and Structure

Rigorous characterization is essential to confirm the structure, stability, and functionality of these gene delivery vectors. The following experimental protocols are standard in the field.

Key Methodologies for LNP Analysis

Protocol 1: Assessing LNP Size and Stability Using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

- Objective: To determine the average particle size, polydispersity index (PDI, a measure of size distribution), and physical stability of LNPs under storage conditions [18].

- Materials: LNP formulation, dispersant (e.g., 8.7% sucrose in Tris buffer, pH 7.4), DLS instrument (e.g., Malvern Nano ZS), polystyrene cuvettes [18].

- Procedure:

- Dilute the LNP sample in an appropriate dispersant (e.g., 50 µL LNPs into 1450 µL dispersant) to achieve optimal scattering intensity.

- Transfer the diluted sample to a polystyrene cuvette.

- Place the cuvette in the DLS instrument pre-equilibrated to 25°C.

- Set parameters: dispersant refractive index, viscosity, equilibration time of 120 s.

- Perform measurement. The instrument analyzes fluctuations in scattered light to calculate hydrodynamic diameter and PDI.

- Data Interpretation: A lower PDI (<0.2) indicates a more monodisperse, homogeneous sample. Studies show that LNPs in the 80–100 nm range often demonstrate superior stability during long-term storage at 4°C and -20°C [18].

Protocol 2: Visualizing LNP Morphology via Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-TEM)

- Objective: To observe the internal and external structure, lamellarity, and morphology of LNPs in a frozen-hydrated, near-native state [18].

- Materials: LNP formulation, cryo-TEM instrument, holey carbon grid, vitrification apparatus (plunger).

- Procedure:

- Apply a small volume (3-5 µL) of the LNP sample onto a glow-discharged holey carbon grid.

- Blot away excess liquid with filter paper to form a thin liquid film across the grid holes.

- Rapidly plunge-freeze the grid into a cryogen (typically liquid ethane) to vitrify the water, preventing ice crystal formation.

- Transfer the grid under liquid nitrogen to the cryo-TEM holder and insert into the microscope.

- Image the particles at low dose and under cryo-conditions to minimize radiation damage.

- Data Interpretation: Cryo-TEM micrographs reveal the spherical structure of LNPs, the integrity of the lipid bilayer, and the presence of an electron-dense core, confirming successful mRNA encapsulation [18].

Key Methodologies for Viral Vector Analysis

Protocol 3: Determining Viral Titer and Purity

- Objective: To quantify the concentration of functional viral vector particles and assess purity relative to non-infectious or empty capsids.

- Materials: Viral vector prep, qPCR kit, cell line permissive to the virus, tissue culture reagents, SDS-PAGE equipment.

- Procedure (Functional Titer):

- Transduction: Serially dilute the viral vector and apply to permissive cells.

- Analysis: After an appropriate period, analyze cells for transgene expression (e.g., by flow cytometry if it's a fluorescent protein) or resistance to selection antibiotics.

- Calculation: The functional titer (e.g., Transducing Units/mL, TU/mL) is calculated based on the dilution and percentage of positive cells.

- Procedure (Physical Titer - qPCR):

- Digestion: Treat the viral prep with DNase to degrade any unpackaged DNA.

- Lysis: Lyse the virus particles to release the encapsulated genome.

- qPCR: Perform qPCR using primers specific to a conserved region of the viral genome (e.g., the WPRE element in LV). Compare to a standard curve of known concentration.

- Data Interpretation: The ratio of physical titer (genome copies/mL) to functional titer (TU/mL) indicates the fraction of particles that are functional. A high ratio suggests many empty or defective particles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful research and development in gene delivery rely on a suite of critical reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments and general formulation workflows.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Vector Development

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids (e.g., SM-102, ALC-0315) | The core functional lipid for mRNA encapsulation and endosomal escape in LNP formulations [18] [19]. |

| PEG-Lipids (e.g., DMG-PEG2000) | Used to control LNP size, improve colloidal stability, and reduce nonspecific protein adsorption during storage and in vivo administration [19] [20]. |

| Structural Lipids (DSPC, Cholesterol) | Provide the structural backbone and bilayer stability for LNPs, mimicking biological membranes and aiding in fusion [18] [20]. |

| Microfluidic Mixers | Essential equipment for the scalable and reproducible production of LNPs by rapidly mixing lipid and aqueous phases in a controlled manner [20]. |

| Cryo-TEM and DLS Instrumentation | Critical analytical tools for characterizing the morphology, size, and size distribution of both LNPs and viral particles [18]. |

| Quant-it RiboGreen RNA Assay Kit | A fluorescent assay used to accurately determine RNA encapsulation efficiency within LNPs by measuring free vs. total RNA [22]. |

| Viral Envelope Proteins (e.g., VSV-G) | Commonly used pseudotyping glycoproteins for Lentiviral vectors, which determine tropism and enable efficient transduction of a broad range of cell types [1]. |

The choice between LNPs and viral capsids is not a matter of superiority, but of strategic alignment with therapeutic goals. LNP's synthetic, modular composition offers flexibility, scalability, and a favorable safety profile for transient expression, making it ideal for vaccines and in vivo gene editing. In contrast, the complex, evolved biology of viral capsids provides unrivalled delivery efficiency and potential for long-term gene expression, which is necessary for many monogenic disorders, albeit with challenges related to immunogenicity and manufacturing. Future directions point toward hybrid and engineered approaches—such as cell-specific targeting ligands for LNPs and engineered capsids to evade immunity—that leverage the strengths of both blueprints to unlock the full potential of genetic medicine.

Introducing foreign genetic material into cells is a cornerstone of modern biological research and therapeutic development. The two predominant methods for achieving this are viral transduction and non-viral transfection, specifically using Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs). While both share the same ultimate goal, their fundamental mechanisms of action—from cellular entry to intracellular trafficking and payload delivery—are profoundly different. Viral transduction leverages billions of years of viral evolution to achieve highly efficient, receptor-mediated entry and, in some cases, genomic integration. [23] [24] In contrast, LNP-mediated transfection utilizes synthetic lipid-based carriers to encapsulate and protect genetic payloads, facilitating delivery through endocytic pathways and subsequent endosomal escape. [25] [3] This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these mechanisms, supported by experimental data and protocols, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal system for their specific applications.

Core Mechanisms of Action

Viral Vector Transduction

Transduction is a process that utilizes viral vectors to deliver genetic material into a cell. [23] Engineered viral vectors are modified to carry a therapeutic transgene while typically being rendered replication-incompetent. The process is characterized by its high efficiency and reliance on specific receptor-ligand interactions.

Figure 1: Viral Transduction Pathways for AAV and Lentivirus Vectors. The process begins with receptor binding and culminates in different outcomes based on the viral serotype.

The key steps in viral transduction, as illustrated in Figure 1, involve:

- Receptor Binding: Viral vectors bind to specific cell surface receptors (e.g., AAV2 uses heparan sulfate proteoglycan), which determines their tropism and tissue specificity. [24]

- Cellular Uptake: The vector-receptor complex enters the cell via receptor-mediated endocytosis or, in some cases, direct membrane fusion. [24]

- Uncoating: The viral capsid is degraded within the endosome, releasing the viral genome into the cytoplasm. [26]

- Genome Processing and Trafficking: The genetic payload is processed and trafficked to the nucleus. For lentiviruses (RNA viruses), this involves reverse transcription and nuclear import of the resulting DNA. For AAV (ssDNA virus), this involves second-strand synthesis of its single-stranded DNA genome. [24] [26]

- Transgene Fate: Lentiviral vectors integrate their DNA into the host cell genome, leading to stable, long-term transgene expression. AAV vectors typically persist as non-integrating episomes in the nucleus, providing durable expression in non-dividing cells. [24] [26]

LNP-Mediated Transfection

Transfection is the process of introducing nucleic acids into cells using non-viral methods, with Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) being a leading technology. [23] [27] LNPs are synthetic, multi-component carriers that encapsulate and protect genetic material. Their mechanism is distinct from viral vectors and does not involve specific receptor targeting in its basic form.

Figure 2: LNP-Mediated Transfection Pathway and Intracellular Barriers. The process is less efficient than viral transduction due to several intracellular barriers.

The key steps in LNP-mediated transfection, as illustrated in Figure 2, involve:

- Cell Membrane Interaction: Positively charged LNPs interact with the negatively charged cell membrane, leading to adsorption and initiation of uptake. [13]

- Cellular Uptake: LNPs are internalized via endocytosis, primarily through clathrin-mediated or other endocytic pathways, forming an endosome. [13]

- Endosomal Trafficking and Acidification: The endosome matures and its internal pH drops. This acidic environment (pH ~6.0-6.5) protonates the ionizable lipids within the LNP, giving them a positive charge. [28]

- Endosomal Escape: The protonated ionizable lipids promote fusion with or destabilization of the endosomal membrane. This is often visualized by the recruitment of galectin proteins, which mark damaged endosomal membranes. [28] Recent studies show that only a small fraction of RNA is actually released from these galectin-marked endosomes, representing a major efficiency barrier. [28]

- Payload Release: The nucleic acid (e.g., mRNA, siRNA) is released into the cytosol, where it can be translated by ribosomes (mRNA) or engage the RNA-induced silencing complex (siRNA). The LNP components and payload can segregate during endosomal sorting, further reducing efficiency. [28]

Comparative Experimental Data

To objectively compare the performance of viral vectors and LNPs, key quantitative data from the literature is summarized in the tables below.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Characteristics Between Viral Vectors and LNPs

| Characteristic | Viral Vectors (LV, AAV) | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Experimental Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Mechanism | Receptor-mediated transduction [24] | Chemical/physical transfection [23] [27] | Defined by the presence or absence of a viral capsid. |

| Primary Uptake Route | Receptor-mediated endocytosis / Membrane fusion [24] | Endocytosis (e.g., clathrin-mediated) [13] | Viral entry is highly specific; LNP entry is generally non-specific. |

| Payload Location | Nuclear (for DNA vectors) [24] | Cytosolic [3] | Suits different applications: gene editing/stable expression (viral) vs. mRNA/siRNA (LNP). |

| Expression Kinetics | Long-term (stable integration or episomal persistence) [23] [24] | Transient (hours to days) [3] | LNP kinetics ideal for vaccines; viral for correcting genetic defects. |

| Typical Payload | DNA (ssDNA for AAV, RNA for LV) [24] | RNA (mRNA, siRNA) or DNA [25] [3] | LNPs have more versatile payload capacity. |

| Immunogenicity | Moderate to High (can trigger immune responses) [23] [3] | Low to Moderate (lower immunogenicity) [3] [13] | LNP's lower immunogenicity allows for repeated dosing. [3] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance and Practical Considerations

| Parameter | Viral Vectors (LV, AAV) | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | References & Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery Efficiency | High (evolved infection mechanism) [3] | Variable, can be high but faces intracellular barriers [28] [3] | A key inefficiency for LNPs is limited endosomal escape. [28] |

| Tropism / Targeting | High (natural and engineered tropism) [24] | Lower, but can be engineered with ligands [3] [13] | Viral serotypes (e.g., AAV2, AAV9) have innate tissue preferences. [24] |

| Cargo Capacity | Limited (~4.7 kb for AAV) [23] | Large (>10 kb), more versatile [25] [3] | AAV's small capacity is a major limitation, overcome by dual-vector approaches. [9] |

| Manufacturing | Complex, time-consuming, costly [3] [13] | Simplified, scalable, commercially viable [3] [13] | LNP scalability was demonstrated during COVID-19 vaccine production. [3] |

| Endosomal Escape Efficiency | Highly efficient (viral uncoating) [24] | Inefficient (rate-limiting step); only a fraction of RNA is released [28] | Live-cell microscopy showed only ~20% of mRNA-LNP damaged endosomes contained detectable mRNA. [28] |

| Safety Profile | Risk of insertional mutagenesis (LV) and immunogenicity [23] [3] | Safer; no genomic integration, lower immunogenicity [25] [3] | LNP toxicity is primarily associated with lipid composition. [3] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a deeper understanding of the data generating these comparisons, key experimental methodologies are outlined below.

Protocol for Quantifying LNP Endosomal Escape Efficiency

This protocol is based on live-cell and super-resolution microscopy studies that directly visualize the inefficiencies in LNP-mediated cytosolic delivery. [28]

Objective: To quantify the efficiency of endosomal escape and RNA release for MC3-based LNPs. Key Reagents:

- Fluorescently labeled siRNA or mRNA (e.g., AlexaFluor 647-siRNA, Cy5-mRNA).

- MC3-based LNPs formulated with the labeled RNA.

- Cell line of interest (e.g., HeLa, HEK-293).

- Galectin-9 fluorescent protein marker (e.g., Galectin-9-GFP) to detect endosomal membrane damage.

- Live-cell imaging medium.

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Seed cells onto glass-bottom imaging dishes and culture until they reach 60-80% confluency.

- Transfection: Treat cells with a defined dose of fluorescent RNA-LNPs (e.g., 50 nM for siRNA-LNPs, 0.75 µg/mL for mRNA-LNPs) in live-cell imaging medium. [28]

- Live-Cell Imaging: Use fast live-cell microscopy to image cells over time (starting from 1 hour post-transfection). Capture simultaneous channels for the fluorescent RNA signal (e.g., Cy5) and the galectin-9 damage sensor (e.g., GFP).

- Image Analysis:

- Identify individual endosomes that show de novo recruitment of galectin-9.

- For each galectin-9-positive endosome, quantify the presence or absence of the fluorescent RNA signal.

- Calculate the "hit rate" as the percentage of galectin-9-positive endosomes that contain a detectable RNA signal.

- Expected Outcome: The hit rate for siRNA-LNPs is typically 67-74%, while for mRNA-LNPs it is significantly lower, around 20%, indicating a major barrier in productive mRNA cargo release. [28]

Protocol for Evaluating Viral Transduction Efficiency and Specificity

Objective: To determine the transduction efficiency and tropism of a specific viral vector (e.g., AAV or Lentivirus). Key Reagents:

- Recombinant viral vector (e.g., AAV2, AAV9, LV) carrying a reporter gene (e.g., GFP, luciferase).

- Target cell lines (including primary cells if applicable) with known receptor expression profiles.

- Appropriate cell culture media and supplements.

- Transduction enhancers (e.g., polybrene for LV).

- Flow cytometer or fluorescence microscope for analysis.

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Seed different target cell lines at an optimal density.

- Viral Transduction: Treat cells with a range of viral vector doses (Multiplicity of Infection - MOI) in the presence or absence of specific transduction enhancers. Include controls (non-transduced cells).

- Incubation and Expression: Incubate cells for the required time to allow for transgene expression (e.g., 48-72 hours).

- Efficiency Analysis:

- For reporter genes: Analyze cells via flow cytometry to quantify the percentage of GFP-positive cells (transduction efficiency) and mean fluorescence intensity (expression level).

- For functional genes: Use RT-qPCR to measure transgene mRNA levels or a functional assay relevant to the delivered gene.

- Specificity/Tropism Confirmation: Perform blocking experiments with excess soluble receptor (if available) to confirm receptor-specific entry. Compare efficiency across cell lines with varying receptor expression levels.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for Gene Delivery Research

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Adeno-associated Virus (AAV) Vectors | Small, single-stranded DNA vectors with low immunogenicity and multiple serotypes for specific tropism (e.g., AAV2 for liver, AAV9 for CNS). [24] | In vivo gene therapy for retinal diseases (Luxturna), hereditary hearing loss. [9] |

| Lentiviral (LV) Vectors | RNA vectors that integrate into the host genome, enabling stable, long-term transgene expression in dividing and non-dividing cells. [24] | Generation of stable cell lines, CAR-T cell therapy ex vivo. [9] [24] |

| Ionizable Cationic Lipids (e.g., MC3) | Key component of LNPs; protonated in acidic endosomes to disrupt the endosomal membrane and facilitate cargo escape. [28] | Formulating LNPs for siRNA (Patisiran) and mRNA therapeutics. [28] |

| Galectin-9 Fluorescent Marker | A sensitive biosensor that recruits to sites of endosomal membrane damage, used to visualize and quantify LNP-induced endosomal escape events. [28] | Live-cell imaging assays to study the efficiency and mechanisms of endosomal escape. [28] |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI) | A cationic polymer that condenses nucleic acids into "polyplexes" for delivery; can be used for both DNA and RNA transfection. [25] [24] | A common, high-efficiency (but sometimes cytotoxic) transfectant for in vitro studies in easy-to-transfect cell lines. [25] |

| Electroporation Systems | Physical method using electrical pulses to create transient pores in the cell membrane for nucleic acid entry. [25] [24] | Transfection of hard-to-transfect cells like primary cells and stem cells. [25] [24] |

The fundamental actions of viral vector transduction and LNP-mediated transfection are distinct, leading to clear trade-offs that dictate their application in research and therapy. Viral vectors excel in delivering high-efficiency, long-term, and targeted gene expression, making them indispensable for in vivo gene therapy and creating stable cell models. Their limitations include immunogenicity, limited cargo capacity, and complex manufacturing. [23] [3] [24] LNPs offer a safer, more versatile, and scalable platform ideal for transient expression applications, such as mRNA vaccines and siRNA silencing. Their primary challenge is overcoming intracellular barriers to achieve consistently high delivery efficiency across diverse cell types. [25] [28] [3] The choice between these systems is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with the experimental or therapeutic goal. Future progress will likely involve hybrid approaches and continued innovation to overcome the inherent limitations of each platform, further expanding the toolbox for genetic medicine.

Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Applications in Practice

The choice between in vivo and ex vivo therapeutic strategies is a fundamental consideration in advanced therapy medicinal product (ATMP) development. This decision is intrinsically linked to the selection of a gene delivery platform, each with distinct implications for research, manufacturing, and clinical application. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and viral vectors represent two leading technologies that enable these paradigms, offering contrasting profiles in efficiency, safety, and therapeutic durability. This guide provides an objective comparison of these platforms, mapping their performance characteristics to appropriate treatment strategies across diverse disease contexts to inform research and drug development decision-making.

The table below synthesizes the core relationship between delivery platforms and therapeutic paradigms, highlighting how inherent platform characteristics direct their application toward specific treatment strategies.

Table 1: Mapping Delivery Platforms to Therapeutic Paradigms

| Feature | In Vivo Paradigm | Ex Vivo Paradigm |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Platform | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) [29] [3] | Viral Vectors (Lentivirus, AAV) & Electroporation [30] [29] |

| Description | Therapy administered directly to the patient; editing occurs inside the body [29] | Patient cells harvested, modified outside the body, then re-infused [29] |

| Therapeutic Duration | Transient expression (e.g., mRNA delivery) [3] | Long-term or permanent expression (e.g., genomic integration) [3] |

| Key Advantages | Non-invasive administration; suitable for inaccessible tissues; scalable production [29] [3] | High precision editing; controlled conditions; reduced immune concerns [29] |

| Key Limitations | Potential off-target effects; lower efficiency in some tissues; immune reactions [30] | Complex, costly manufacturing; limited to cell types that can be cultured [29] |

| Therapeutic Examples | NTLA-2001 (TTR Amyloidosis), CTX310 (Cardiovascular Disease) [29] | Casgevy (Sickle Cell Disease), Lyfgenia (Sickle Cell Disease) [29] |

Technical Performance and Experimental Data

A direct comparison of technical performance metrics is essential for platform selection. The following table summarizes quantitative and qualitative data on the key characteristics of LNPs and viral vectors.

Table 2: Technical Performance Comparison of Lipid Nanoparticles vs. Viral Vectors

| Performance Metric | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Viral Vectors (AAV, Lentivirus) |

|---|---|---|

| Delivery Efficiency | High for liver targets; improving for extrahepatic tissues [31] [32] | Very high, particularly with AAV and lentiviral vectors [3] |

| Payload Capacity | Versatile; suitable for mRNA, siRNA, CRISPR components [3] | Limited cargo size, especially for AAV [29] [3] |

| Immune Response | Lower immunogenicity; suitable for repeated dosing [3] | Higher immunogenicity; risk of pre-existing immunity [3] |

| Tissue Targeting | Improving with novel formulations & membrane modifications [31] [33] | Naturally high tropism; can be engineered for specificity [34] [33] |

| Gene Integration | Typically non-integrating; transient expression [3] | Lentiviruses integrate; AAV mostly episomal (long-term expression) [3] |

| Manufacturing Scalability | Highly scalable; demonstrated at global scale [29] [3] | Complex and costly to scale; challenges in consistency [3] |

| Key Safety Concerns | Reactogenicity, lipid toxicity [35] | Insertional mutagenesis, immune toxicity [3] |

| Representative Therapy | mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines, NTLA-2001 [35] [29] | Zolgensma, Luxturna, Lyfgenia [29] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Ex Vivo Workflow: CRISPR-Edited Cell Therapies

The ex vivo paradigm, used in FDA-approved therapies like Casgevy, involves a multi-stage process where genetic modification occurs outside the patient's body [29].

Key Methodological Details:

- Cell Harvest: CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) are collected from the patient via apheresis following mobilization, or directly from bone marrow [29].

- Ex Vivo Gene Editing: Cells are transfected using electroporation (for CRISPR ribonucleoproteins) or transduced with lentiviral vectors. For Casgevy, electroporation delivers the CRISPR-Cas9 system to precisely edit the BCL11A gene enhancer in HSPCs [29].

- Cell Expansion and Quality Control: Edited cells are cultured ex vivo to expand the population and undergo rigorous testing to ensure viability, purity, and editing efficiency before reinfusion.

- Patient Conditioning and Reinfusion: Patients receive myeloablative conditioning (e.g., busulfan) to clear marrow space. The edited HSPCs are then infused back into the patient to engraft and reconstitute the hematopoietic system with genetically corrected cells [29].

In Vivo Workflow: Systemic LNP Administration

The in vivo paradigm, exemplified by therapies like NTLA-2001, delivers the genetic medicine directly to the patient via systemic administration [29].

Key Methodological Details:

- LNP Formulation: LNPs are synthesized to encapsulate mRNA encoding CRISPR-Cas9 and a single guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting the therapeutic gene (e.g., the TTR gene for NTLA-2001). Microfluidic mixing is a standard method for producing monodisperse, reproducible LNPs [32] [29].

- Systemic Administration and Targeting: The formulated LNPs are administered intravenously. Following IV injection, many current LNP systems naturally accumulate in the liver via apolipoprotein E (ApoE)-mediated uptake, effectively targeting hepatocytes [31].

- Intracellular Delivery and Endosomal Escape: After cellular uptake via endocytosis, the ionizable lipids within the LNPs become protonated in the acidic endosomal environment. This promotes a hexagonal lipid phase structure that disrupts the endosomal membrane, releasing the genetic payload into the cytoplasm [32].

- Gene Editing and Phenotypic Effect: The delivered Cas9 mRNA is translated into functional protein, which complexes with the sgRNA to form the active nuclease. This complex introduces a double-strand break in the target genomic DNA, leading to gene knockout via non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). Successful knockout of the TTR gene in hepatocytes results in a sustained reduction of pathogenic TTR protein serum levels, as demonstrated in clinical trials for NTLA-2001 [29].

Advanced Engineering and Screening Methodologies

High-Throughput LNP Development

The traditional, sequential approach to LNP formulation is being transformed by integrated high-throughput strategies. These approaches leverage automation and advanced screening to rapidly identify optimal candidates from vast combinatorial libraries [32].

Key Components of the Workflow:

- Combinatorial Lipid Libraries: Automated synthesis enables the rapid generation of hundreds to thousands of unique ionizable lipids with systematic structural variations, creating a vast chemical space for exploration [32].

- Automated Microfluidic Formulation: Microfluidic chips enable the parallel synthesis of LNP libraries in multi-well plates (up to 384 per plate), ensuring monodispersity and high batch-to-batch consistency with minimal reagent consumption [32].

- High-Throughput Characterization (HTC): Automated systems using multi-well dynamic light scattering (DLS), spectroscopy, and other techniques rapidly profile LNP size, stability, charge, and encapsulation efficiency across thousands of formulations [32].

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Multiplexed in vitro assays and in vivo barcoding strategies assess cellular uptake, transfection efficiency, cytotoxicity, and biodistribution to identify candidates with desirable biological performance [32].

- Machine Learning Integration: Data from HTC and HTS feed into predictive models like COMET (Composite Material Transformer), a transformer-based neural network trained on large LNP datasets. COMET can predict LNP efficacy and guide the design of improved formulations in an iterative, closed-loop process [36].

Directed Evolution of Viral Vectors

To overcome limitations such as off-target transduction and immune recognition, viral vectors can be engineered for enhanced specificity and efficiency through directed evolution [33].

Protocol for AAV Capsid Engineering via In Vivo Selection:

- Library Generation: Create a diverse library of AAV capsid mutants, for example, by inserting random 7-amino acid peptides into the capsid protein of a parental serotype like AAV9 [33].

- In Vivo Selection: Administer the mutant library systemically to animal models (e.g., transgenic Cre mice). Employ focused ultrasound blood-brain barrier opening (FUS-BBBO) in specific brain regions to enable localized viral entry [33].

- Recovery and Analysis: Recover viral DNA specifically from the targeted brain regions. Use Cre-dependent PCR to selectively amplify genomes that have successfully transduced neurons. Sequence the recovered capsid variants to identify enriched mutants [33].

- Validation: Package selected mutant capsids and validate their performance against the parental serotype. The goal is to identify variants with enhanced targeting specificity, reduced off-target organ transduction, and improved neuronal tropism [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of these paradigms requires a suite of specialized tools and reagents. The following table details key solutions for developing and optimizing gene delivery systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Gene Delivery Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| LNP Components | Ionizable Lipids (e.g., C12-200, LP01), PEG-lipids, Cholesterol, Helper Lipids (DOPE, DSPC) [32] [29] | Structural components of LNPs; ionizable lipids are critical for endosomal escape and efficacy [32]. |

| Microfluidic Systems | PreciGenome NanoGenerator, other commercial microfluidic chips [29] | Enable reproducible, high-throughput synthesis of monodisperse LNPs for research and pre-clinical testing [32] [29]. |

| Characterization Instruments | High-Throughput Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), Microplate Readers, SAXS instruments [32] | Automated, multi-parametric physicochemical characterization of LNP libraries (size, PDI, stability, encapsulation) [32]. |

| Viral Vector Engineering Tools | AAV Capsid Libraries (e.g., 7-mer insertion libraries), Cre-transgenic Mice, Packaging Cell Lines [33] | Key reagents for directed evolution of viral vectors to achieve enhanced tissue tropism and reduced immunogenicity [33]. |

| Analytical & Screening Tools | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), Barcoded Library Strategies, In Vivo Imaging Systems (IVIS) [32] [33] | Critical for deconvoluting complex screening results, tracking biodistribution, and quantifying editing efficiency. |

| Cell Culture & Editing Reagents | Hematopoietic Stem Cell Media, CRISPR-Cas9 RNP Complexes, Electroporation Systems [29] | Essential for ex vivo gene editing workflows, enabling the modification and expansion of patient-derived cells [29]. |

The strategic selection between in vivo and ex vivo paradigms, and their corresponding delivery platforms, is guided by the specific therapeutic objective. The ex vivo approach, largely enabled by electroporation and viral vectors, offers a controlled, precise method for modifying cells outside the body and is the foundation of the first approved CRISPR therapies. In contrast, the in vivo paradigm, significantly advanced by LNP technology, provides a less invasive, directly administered, and highly scalable option, as demonstrated by therapies in development for liver and metabolic diseases.

Emerging technologies such as high-throughput screening, machine learning-guided LNP design [36], and directed evolution of viral capsids [33] are rapidly enhancing the performance of both platforms. The future of gene therapy will likely see a more refined application of each platform based on disease pathology and target tissue, and potentially even hybrid strategies that combine their respective strengths to achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes.

The debate between viral vector and non-viral delivery systems represents a central theme in gene therapy research. While lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have gained prominence for RNA-based vaccines and therapeutics, viral vectors, particularly recombinant adeno-associated viruses (rAAVs), have established a proven track record with multiple FDA-approved treatments for rare diseases. These successful clinical applications highlight the unique advantages of viral vectors, including their ability to provide long-term transgene expression and their high tissue specificity, which are critical for addressing the root cause of many genetic disorders.

This guide objectively examines the performance of approved rAAV therapies, using Zolgensma and Luxturna as primary case studies, and compares them with emerging alternatives like LNPs, supported by experimental and clinical data.

The following table summarizes key FDA-approved rAAV-based gene therapies, their indications, and mechanisms of action.

| Therapy Name | Indication | Target Gene / Mechanism | Vector Serotype | Key Clinical Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zolgensma [37] | Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in pediatric patients <2 years | Survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene replacement | AAV9 | Improves motor function and survival; sustained SMN protein expression |

| Luxturna [37] [38] | RPE65 mutation-associated retinal dystrophy | Retinal pigment epithelium-specific 65 kDa protein (RPE65) gene replacement | AAV2 | Improved functional vision; ~70% of patients maintained gains at 4 years [38] |

| Hemgenix [37] | Hemophilia B | Factor IX (FIX) gene replacement | AAV5 | Sustained therapeutic levels of FIX, reducing or eliminating need for prophylaxis |

| Elevidys [37] | Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) in ambulatory children | Microdystrophin gene expression | AAVrh74 | Approved under accelerated approval; increased microdystrophin expression |

| Roctavian [37] | Severe hemophilia A | Factor VIII (FVIII) gene replacement | AAV5 | Sustained FVIII expression, reducing bleeding episodes |

| Kebilidi [37] | Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency | AADC gene replacement | AAV2 | Improved motor and cognitive function |

Performance Analysis: Viral Vectors vs. Emerging Alternatives

Therapeutic Efficacy and Durability

rAAV vectors excel in providing long-lasting therapeutic effects due to their episomal persistence in non-dividing cells, leading to sustained transgene expression. For example, Luxturna has demonstrated durable functional vision improvements, with approximately 70% of patients maintaining gains up to four years post-treatment [38].

In vivo genome editing therapies using rAAV vectors also show promise for durable outcomes. The rAAV-based CRISPR system used in EDIT-101, an investigational therapy for Leber Congenital Amaurosis, was designed to create a permanent genomic correction [39].

Safety and Immunogenicity Profile

While rAAV therapies are generally safe, post-marketing surveillance has identified specific safety profiles that require careful management.

- Luxturna: Clinical trials showed largely mild to moderate adverse events (e.g., conjunctival hyperemia, cataract). However, post-marketing data revealed chorioretinal atrophy (CRA) in 13–50% of treated eyes, particularly in younger patients and often near the injection site [38].

- Common Challenges: Immune responses to the viral capsid or transgene can limit re-administration and, in some cases, impact efficacy and safety. Pre-existing immunity to certain AAV serotypes in human populations can also exclude eligible patients [39] [40].

Manufacturing and Scalability

Manufacturing complexity presents a significant challenge for viral vectors. The production of rAAVs involves complex processes using mammalian cell culture systems, which can be difficult to scale up for commercial supply [40]. Industry partnerships are increasingly requiring higher levels of Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) compliance early in clinical development, adding to the complexity [40].

Experimental Insights: Direct Comparison of Delivery Platforms

The table below compares key technical and performance characteristics of viral and non-viral gene delivery platforms, based on data from preclinical and clinical studies.

| Parameter | rAAV Vectors | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Electroporation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Packaging Capacity | Limited (<4.7 kb) [39] | Higher capacity for RNA and CRISPR ribonucleoproteins [41] | Wide compatibility [41] |

| Expression Durability | Long-term (episomal persistence) [39] | Transient (ideal for short-term editing) [41] [42] | Can be stable if genome integration occurs |

| Typical Administration | In vivo [37] [39] [38] | In vivo or ex vivo [41] [42] | Ex vivo only [41] |

| Primary Safety Concerns | Immunogenicity, off-target editing (CRISPR) [39] [38] | Transient inflammatory responses [41] | Low cell viability, restricted to ex vivo use [41] |

| Manufacturing Scalability | Complex and costly [40] | Highly scalable (e.g., microfluidics) [41] [43] | Not applicable for in vivo use |

| Clinical Proof of Concept | Multiple FDA-approved in vivo therapies [37] | FDA-approved vaccines; in vivo CRISPR therapies in trials (e.g., NTLA-2001) [41] | FDA-approved ex vivo therapy (Casgevy) [41] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Viral Vector Therapies

Protocol: Subretinal Administration of rAAV (Exemplified by Luxturna)

The subretinal injection technique is critical for the success of retinal gene therapies like Luxturna [38].

Key Methodological Details:

- Dosage: Luxturna is administered at a standardized dose of 1.5 × 10^11 vector genomes (vg) per eye [38].

- Immunosuppression: Oral corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) are initiated three days prior to administration to minimize immune responses, with a gradual taper over the following ten days [38].

- Efficacy Assessment: Functional vision is quantitatively assessed using the Multi-Luminance Mobility Test (MLMT), where patients navigate an obstacle course under varying light conditions (from 400 lux to 1 lux) [38].

Protocol: Systemic rAAV Delivery (Exemplified by Zolgensma)

Zolgensma utilizes a different administration route to target motor neurons.

Key Methodological Details:

- Vector Serotype: AAV9 is selected for its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier after intravenous administration, enabling direct targeting of motor neurons [37].

- Dosing: A one-time infusion is designed to provide lifelong SMN protein expression.

- Outcome Measures: Clinical trials assessed outcomes based on motor milestone achievement (e.g., head control, sitting unassisted) and event-free survival (freedom from permanent ventilation or death) [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Viral Vector Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Context | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| AAV Serotype Libraries (e.g., AAV2, AAV5, AAV8, AAV9, AAVrh74) | Determine tissue tropism and transduction efficiency for different target organs. | AAV9 for CNS targets; AAV2 for retinal delivery [37] [39] [38]. |

| Cell-Penetrating Peptides (e.g., Transportan) | Enhance viral vector uptake in difficult-to-transfect cells via bystander uptake and macropinocytosis [44]. | Co-incubation with AAV to improve transfection efficiency in primary retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells and macrophages [44]. |

| Minicircle DNA (mcDNA) | A compact, supercoiled DNA vector lacking bacterial sequences, enabling higher and more persistent transgene expression [42]. | Used in non-viral LNP systems (e.g., NCtx) for stable CAR integration in T cells [42]. |

| Ionizable Cationic Lipids (e.g., LP01) | Key component of LNPs; positively charged at low pH to complex with nucleic acids and promote endosomal escape [41]. | Formulated in NTLA-2001 LNP for in vivo CRISPR/Cas9 delivery to the liver [41]. |

| Transposase Systems (e.g., SB100x mRNA) | Enable genomic integration of delivered transgenes for stable long-term expression in dividing cells [42]. | Codelivery with CAR-encoding mcDNA in LNPs to generate persistent in vivo CAR-T cells [42]. |

Viral vectors have demonstrated undeniable success, transitioning from experimental tools to approved medicines for devastating rare diseases. Their proven ability to provide durable therapeutic effects in humans, as evidenced by Zolgensma and Luxturna, sets a high benchmark for any gene delivery system.

The future of gene therapy is not necessarily a choice between viral and non-viral systems, but rather a strategic selection based on the therapeutic objective. rAAVs currently excel in long-term gene replacement strategies, while LNPs offer a versatile platform for transient expression and in vivo genome editing. Emerging innovations, such as the use of ultra-compact CRISPR systems to fit rAAV packaging constraints [39] and targeted LNPs for specific cell types [42], will continue to push the boundaries of both platforms, ultimately expanding the therapeutic arsenal available to researchers and clinicians.

The advent of gene therapy has introduced powerful platforms for treating genetic disorders, cancers, and infectious diseases. The clinical success of these therapies hinges on the delivery vectors that transport genetic material into target cells. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and viral vectors represent the two most prominent delivery technologies, each with distinct advantages and limitations. While viral vectors like lentiviruses and adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) offer high transduction efficiency and potential long-term gene expression, they face challenges related to immunogenicity, pre-existing immunity, and insertional mutagenesis risks [3]. LNPs, clinically validated by mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, provide a non-viral alternative with favorable safety profiles, transient expression, and redosing capability [3]. This guide objectively compares the performance of these platforms, focusing on recent clinical breakthroughs that underscore LNPs' transformative role in modern medicine, from prophylactic vaccines to precision gene editing.

Comparative Analysis: LNP vs. Viral Vector Performance

Table 1: Head-to-Head Comparison of Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) and Viral Vectors

| Performance Characteristic | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Viral Vectors (Lentivirus, AAV) |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Fuse with cell membrane to deliver payload directly to cytoplasm [3] | Infect cells; may integrate into host genome (lentivirus) or remain episomal (AAV) [3] |

| Typical Gene Expression | Transient (ideal for vaccines, short-term therapies) [3] | Long-term or permanent (ideal for correcting genetic defects) [3] |

| Immune Response | Lower immunogenicity; suitable for repeated dosing [3] [45] | Often triggers stronger immune response; limits redosing potential [3] |

| Delivery Efficiency | High for systemic delivery, but tissue targeting requires engineering [3] [46] | Naturally high efficiency; can be engineered for precise tissue targeting [3] |

| Manufacturing & Scalability | Relatively easy to scale; commercially viable production [3] | Complex and costly large-scale production [3] |

| Key Safety Concerns | Generally strong safety profile; lipid composition must be optimized to minimize toxicity [3] | Risk of insertional mutagenesis and immune reactions [3] |

| Therapeutic Examples | COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, NTLA-2001 (CRISPR for ATTR amyloidosis) [3] [45] | CAR-T cell therapies (Kymriah, Yescarta), Luxturna (retinal disease) [47] [48] |

Table 2: Quantitative Clinical and Preclinical Data for LNP-Based Therapies

| Therapeutic Application | LNP Formulation / Developer | Key Experimental Model & Dose | Reported Efficacy Outcome | Reported Safety Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR for ATTR Amyloidosis (NTLA-2001) | Intellia Therapeutics LNP [45] | Human Phase 1 Trial: Single 55 mg dose | ~90% median reduction in serum TTR at Day 28 [45] | Generally well tolerated; mild infusion-related reaction in 1 of 3 patients upon redosing [45] |

| In vivo CAR-T for B-cell Leukemia | NCtx LNP (anti-CD7/CD3 targeted) [49] | Murine Xenograft Model: Single IV dose | Robust CAR-T cell generation, effective tumor control, and significantly improved survival [49] | Efficient & specific; no major adverse events reported in the study [49] |

| Prophylactic Vaccine (Novel Lipids) | Acuitas Next-Gen LNPs [46] | Preclinical Model: Intramuscular injection | Novel lipids induced equivalent neutralizing antibody titers at a 5-fold lower dose than benchmark ALC-315 [46] | Favorable reactogenicity profiles comparable to ALC-315 [46] |

| Cancer Vaccine | ALC-315 LNP (unmodified mRNA) [46] | Preclinical Model: Intramuscular vs. IV lipoplexes | Induced stronger antigen-specific CD8 T-cell response vs. modified mRNA; equal/superior immunity at one-tenth the dose vs. lipoplexes [46] | Not specified in source, but platform is clinically validated [46] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key LNP Breakthroughs

Protocol: In Vivo Generation of CAR-T Cells Using Targeted LNPs

This protocol is adapted from a study demonstrating the use of targeted LNPs for in vivo CAR-T cell generation, a significant advancement over traditional ex vivo manufacturing [49].

- 1. LNP Formulation and Functionalization: The novel lipid nanoparticle, termed NCtx, is formulated to encapsulate two genetic payloads: a minicircle DNA (mcDNA) encoding the CAR construct and mRNA encoding the SB100x transposase. The LNP surface is then functionalized with T cell-specific targeting ligands, such as anti-CD7 and anti-CD3 binders, to achieve specificity [49].

- 2. In Vitro Specificity and Transfection Efficiency: Primary T cells are isolated and incubated with the NCtx formulation. Specificity is evaluated using flow cytometry to confirm preferential binding and uptake by T cells. Transfection efficiency is assessed by measuring CAR expression via flow cytometry and functionality through antigen-specific cytotoxicity assays and cytokine release profiles [49].

- 3. In Vivo Efficacy in Xenograft Models: Immunodeficient mice are humanized by engrafting them with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or CD34+ stem cells. These mice are then inoculated with B-cell leukemia cells to establish tumors. A single intravenous dose of NCtx is administered. Tumor growth is monitored over time, and mouse survival is tracked. Blood and tissue samples are analyzed to quantify the generation of CAR-T cells and their persistence in vivo [49].

Protocol: Clinical Proof-of-Concept for CRISPR Redosing

This protocol details the methodology from the first-ever clinical demonstration of redosing an in vivo CRISPR-based therapy, highlighting a key advantage of LNP delivery [45].

- 1. Patient Enrollment and Initial Dosing: In the Phase 1 dose-escalation study for NTLA-2001, three patients with hereditary transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis received an initial low dose of 0.1 mg/kg of the investigational therapy. This dose led to a median 52% reduction in serum TTR protein at day 28, which was lower than the target effect [45].