Intrinsic Optical Bistability in Avalanching Nanoparticles: Mechanism, Applications, and Future Directions

This article comprehensively explores intrinsic optical bistability (IOB) in photon avalanching nanoparticles (ANPs), a groundbreaking development in nanoscale photonic materials.

Intrinsic Optical Bistability in Avalanching Nanoparticles: Mechanism, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores intrinsic optical bistability (IOB) in photon avalanching nanoparticles (ANPs), a groundbreaking development in nanoscale photonic materials. We examine the fundamental mechanism of IOB in neodymium-doped KPb2Cl5 nanocrystals, where suppressed nonradiative relaxation and extreme nonlinearity enable history-dependent optical switching. The content covers synthesis methodologies, experimental demonstrations of optical memory and transistor functionality, and analysis of non-thermal bistability origins. Comparative evaluation against conventional nonlinear materials highlights the unprecedented >200th-order nonlinearities and practical implications for optical computing, biomedical sensing, and next-generation microelectronics. This resource provides researchers and drug development professionals with critical insights into harnessing ANPs for advanced optical applications.

Understanding Intrinsic Optical Bistability: From Basic Principles to Avalanching Nanoparticles

Defining Intrinsic Optical Bistability (IOB) and Its Historical Context in Nonlinear Optics

Intrinsic Optical Bistability (IOB) represents a fundamental phenomenon in nonlinear optics where a material exhibits two stable optical output states for a single input condition, with the state selection dependent on the excitation history. This article provides a comprehensive technical examination of IOB, tracing its evolution from theoretical foundations in macroscopic systems to its recent demonstration in nanoscale materials, specifically photon avalanching nanoparticles (ANPs). Within the broader context of ANPs research, we detail the breakthrough discovery of IOB in neodymium-doped KPb₂Cl₅ nanocrystals, elucidate the underlying non-thermal mechanism driven by extreme optical nonlinearities, and present standardized experimental protocols for its observation and characterization. This whitepaper serves as an authoritative resource for researchers and development professionals navigating this cutting-edge intersection of nanotechnology and photonics.

Intrinsic Optical Bistability (IOB) is a nonlinear optical phenomenon characterized by a material's ability to reside in one of two distinct optical states under identical steady-state input conditions. The specific state—typically a "high" (bright, emissive) or "low" (dark, non-emissive) transmission or emission state—depends on the history of the excitation input [1] [2]. This memory effect and discontinuous response differentiate bistable systems from conventional nonlinear optics and form the foundational principle for optical switching and memory applications.

The "intrinsic" qualifier signifies that the bistable behavior originates from the inherent electronic and photophysical properties of the material itself, rather than being imposed by an external apparatus such as an optical cavity [3]. The phenomenon manifests graphically as a hysteresis loop in a plot of output intensity versus input intensity; as the input power is increased, the output remains low until a critical threshold power (Pon) is surpassed, triggering an abrupt transition to the high-output state. Subsequently, when the input power is decreased, the material persists in the high-output state until a lower threshold power (Poff) is reached, at which point it reverts to the low-output state [1] [2]. The region of power between Poff and Pon represents the bistable region where either state is accessible, making IOB materials ideal candidates for binary optical memory and logic gates.

Historical Development and Theoretical Foundations

The pursuit of optical bistability spans several decades, driven by the vision of all-optical computing and signal processing. Early research, predominantly in the 1980s, focused on macroscopic systems where bistability was achieved through a combination of nonlinear media and external feedback mechanisms, most commonly Fabry-Perot resonators [2]. Concurrently, theoretical work explored the potential for intrinsic bistability. A significant conceptual advance was the investigation into composite materials, where theories predicted that sharp resonances and local field enhancements in nonlinear dielectric-metal composites could lower the threshold for bistable behavior [4].

A pivotal milestone occurred in 1979 with the discovery of the photon avalanche (PA) effect by Jay S. Chivian in praseodymium-doped bulk crystals (LaCl₃:Pr³⁺ and LaBr₃:Pr³⁺) [5]. This phenomenon was distinguished by an extreme nonlinearity: a tiny increase in pump power beyond a specific threshold yielded a colossal increase in luminescence intensity. Despite its dramatic effects in bulk crystals, translating the PA phenomenon to the nanoscale proved exceptionally challenging for decades due to increased surface-related losses and heightened complexity in energy transfer dynamics within confined volumes [5].

The historical trajectory of IOB research has thus been a journey from external to internal control, and from bulk to nanoscale. For years, IOB remained largely theoretical for nanoscale applications, with observed bistability often attributed to inefficient thermal effects [1]. The critical turning point has been the recent synthesis and understanding of highly nonlinear avalanching nanoparticles (ANPs), which finally provided a viable, non-thermal pathway to achieve and control IOB at the nanoscale [1] [6] [2].

The Modern Paradigm: IOB in Photon Avalanching Nanoparticles

The most significant recent advancement in IOB research is its demonstration in specific, engineered nanomaterials. A collaborative effort co-led by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Columbia University, and Universidad Autónoma de Madrid produced the first practical demonstration of IOB in nanoscale materials using neodymium-doped KPb₂Cl₅ avalanching nanoparticles [1] [6] [2].

Material Composition and Key Properties

The successful ANPs are characterized by a precise composition and structure, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of IOB-Capable Avalanching Nanoparticles

| Parameter | Specification | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| Core Material | KPb₂Cl₅ (Potassium Lead Chloride) crystal host | Provides a low-phonon energy environment, suppressing non-radiative relaxation [2]. |

| Dopant Ion | Nd³⁺ (Neodymium) | The active ion enabling the photon avalanche mechanism via its specific energy level structure [7] [2]. |

| Particle Size | ~30 nanometers | Enables nanoscale integration and operation at a size comparable to modern microelectronics [1] [6]. |

| Excitation | Infrared laser (resonant with ESA) | Initiates the avalanche process by exciting ions already in an intermediate state [5]. |

| Emission | Upconverted luminescence | The high-energy "bright" state output, resulting from the multi-photon avalanche process [1]. |

The Photon Avalanche Mechanism

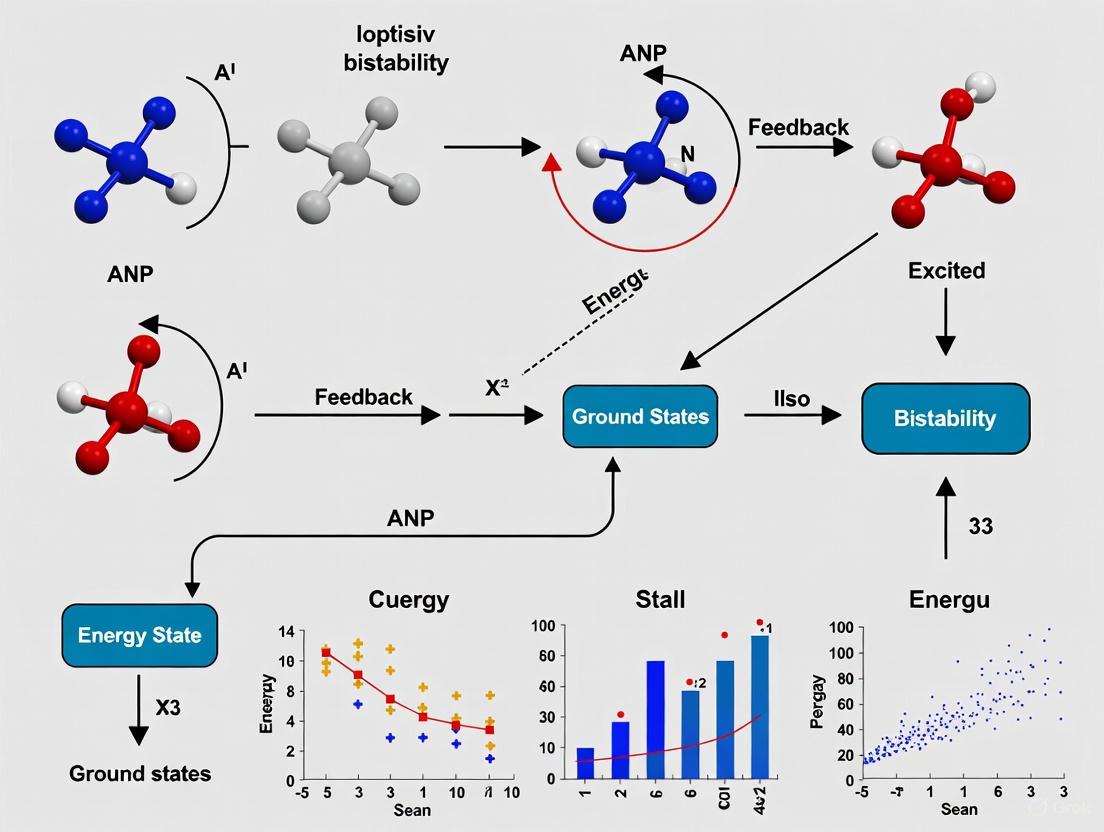

The IOB in these ANPs originates from a sophisticated photon avalanche mechanism, a non-thermal process involving a positive feedback loop. The process can be broken down into the following steps, illustrated in the diagram below:

- Initial Excitation: A single neodymium (Nd³⁺) ion undergoes weak ground-state absorption (GSA) to a higher energy level, followed by non-radiative relaxation to a metastable intermediate state.

- Excited-State Absorption (ESA): An ion in this intermediate state absorbs another photon from the pump laser via ESA, reaching a highly excited state.

- Cross-Relaxation (CR): This highly excited ion transfers part of its energy to a neighboring Nd³⁺ ion in the ground state via a cross-relaxation process. The result is that two ions are now in the intermediate metastable state.

- Positive Feedback Loop: These two ions can then each undergo ESA and CR, potentially creating four ions in the intermediate state. This chain reaction, or "avalanche," leads to an exponential growth in the population of excited ions [5] [7].

- Upconverted Emission: The large population of ions in high-energy states results in the emission of high-energy (visible) photons, which is the "on" state of the system.

This mechanism results in extreme optical nonlinearity, with reported nonlinearity orders exceeding 200th-order [7] [2]. This means a minuscule change in input laser power produces a disproportional, enormous change in output luminescence.

Hysteresis and Optical Memory

The IOB manifests through a characteristic hysteresis loop. Once the avalanche is triggered (above Pon), the high-emission state becomes self-sustaining at pump powers below the initial trigger point. The system remains "on" until the laser power is reduced to a much lower Poff threshold, which breaks the positive feedback loop [1] [2]. The large difference between these two thresholds creates a power window where the nanoparticle's state (bright or dark) depends solely on its immediate past, functionally acting as a nanoscale optical memory bit [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

This section provides detailed methodologies for reproducing and validating IOB in ANPs, based on the protocols established in the seminal Nature Photonics study [2].

Synthesis of IOB-Capable ANPs

Method: The 30 nm Nd³⁺:KPb₂Cl₅ nanoparticles were synthesized via a high-temperature solid-state reaction or a solution-phase hot-injection method [2].

- Precursors: Potassium chloride (KCl), lead chloride (PbCl₂), and neodymium chloride (NdCl₃) are typical precursors.

- Dopant Concentration: The concentration of Nd³⁺ is critical and must be optimized (typically 1-5%) to balance efficient cross-relaxation against concentration quenching effects [5].

- Surface Passivation: Proper ligand exchange or shelling is often necessary to suppress surface-related quenching and enhance environmental stability [1].

Optical Characterization and IOB Observation

Equipment: A standard optical microscopy setup equipped with a tunable, continuous-wave (CW) infrared laser source (e.g., ~1064 nm or ~850 nm, resonant with the Nd³⁺ ESA transition), a high-sensitivity spectrometer or photomultiplier tube (PMT), and a precise laser power controller is required. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Disperse synthesized ANPs in a transparent matrix (e.g., polymer film) or suspend them in a solvent on a microscope slide.

- Power-Dependent Hysteresis Measurement:

- Begin with the laser power well below the anticipated threshold.

- Gradually increase the laser power while measuring the integrated upconverted emission intensity.

- Observe the sharp, discontinuous jump in intensity at Pon.

- After stabilizing in the "on" state, gradually decrease the laser power and record the emission intensity.

- Note the power Poff at which the emission abruptly drops to the baseline level. The hysteresis loop is the region between the upward and downward curves.

- Temporal Switching Experiments:

- Set the laser power to a value within the bistable region (between Poff and Pon).

- Use a brief, high-power laser pulse to "write" the nanoparticle into the "on" state.

- Use a period of very low power or beam blockage to "erase" the nanoparticle back to the "off" state.

- This demonstrates the volatile random-access memory (RAM) functionality [1].

Table 2: Key Experimental Parameters for IOB Observation

| Parameter | Typical Range/Value | Measurement Instrument |

|---|---|---|

| Laser Wavelength | ~850 nm or ~1064 nm (resonant with Nd³⁺ ESA) | Tunable CW IR Laser |

| Laser Power (P_on) | Threshold power specific to sample (e.g., several mW/µm²) | Laser Power Meter / Controller |

| Hysteresis Width | Difference between Pon and Poff | Derived from power-intensity plot |

| Emission Wavelength | Visible range (e.g., ~450-500 nm for KPb₂Cl₅:Nd³⁺) | Spectrometer |

| Nonlinearity Order | >200th-order | Calculated from log-log plot of power vs. intensity [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for IOB-ANP Research

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lanthanide Dopant Salts | Active ion source for photon avalanche. | Neodymium(III) chloride (NdCl₃); purity >99.9% is critical. |

| Crystal Host Precursors | Forms the low-phonon energy nanoparticle matrix. | Potassium chloride (KCl), Lead chloride (PbCl₂). |

| Surface Ligands | Controls nanoparticle growth and prevents aggregation. | Oleic acid, Oleylamine for synthesis; can be exchanged for biocompatibility. |

| Low-Power IR Laser | Primary excitation source for triggering and switching IOB. | Continuous-wave (CW) laser diode at ~850 nm or ~1064 nm. |

| High-Power Pulsed Laser | "Write" pulse for optical memory operation. | Pulsed laser system for temporary high-power excitation. |

Applications and Future Research Directions

The demonstration of IOB in ANPs opens transformative pathways for photonics and computing.

- Nanoscale Optical Memory and Switches: ANPs can function as volatile memory (RAM) where light writes, reads, and erases data, enabling ultra-fast, high-density optical data storage and processing [1] [6].

- Optical Transistors and Logic Gates: The dual-laser excitation scheme, where one laser beam controls the state set by another, demonstrates transistor-like optical switching. This is a fundamental component for building all-optical computers [7] [2].

- High-Density 3D Integration: The nanoparticles' small size and compatibility with direct lithography techniques allow for the fabrication of 3D volumetric interconnects, overcoming the planar density limitations of current electronics [8] [2].

Future research is focused on enhancing the performance and practicality of IOB-ANPs. Key challenges include improving environmental stability, discovering new material compositions to reduce power thresholds further, and integrating these nanoparticles into functional photonic circuit devices [1] [5].

The recent breakthrough in achieving Intrinsic Optical Bistability in photon avalanching nanoparticles marks a pivotal convergence of historical theoretical pursuit and modern nanoscience. The precise engineering of neodymium-doped KPb₂Cl₅ nanocrystals has provided the first robust, nanoscale platform where light can control light with the history-dependent logic essential for computation and memory. The elucidation of the non-thermal, avalanching-based mechanism—characterized by unprecedented nonlinearity and a clear hysteresis loop—provides a new paradigm for the field. As research progresses to optimize these materials and integrate them into photonic systems, IOB-capable ANPs are poised to fundamentally advance the development of next-generation optical computing, neuromorphic photonics, and high-density information processing technologies.

Photon Avalanching (PA) represents a groundbreaking phenomenon in nanophotonics, enabling the generation of high-energy photons with minimal pumping power due to its highly nonlinear optical dynamics [5]. This distinctive process is characterized by a nonlinear upconversion (UC) mechanism where a minute increase in pumping power can trigger a dramatic surge in luminescence intensity—often exceeding 1000-fold [5]. The phenomenon was first observed in 1979 in lanthanide-doped bulk crystals but has recently seen a dramatic resurgence at the nanoscale, propelled by advances in synthesis and sensitive detection technologies [5] [9]. ANPs are typically composed of inorganic crystalline host matrices such as NaYF4, NaGdF4, or LaF3, doped with rare-earth lanthanide ions (e.g., Tm3+, Nd3+, Ho3+) that facilitate the avalanche process through a unique energy-transfer cascade [5]. This whitepaper examines the fundamental principles, material requirements, and characteristic features of PA, with particular emphasis on its intrinsic optical bistability and emerging applications in nanoscopy, sensing, and optical computing.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Material Foundations

Core Photophysical Processes

The photon avalanche mechanism operates through a precise orchestration of three interconnected photophysical processes that create a positive feedback loop for population growth in excited states [9].

Weak Ground-State Absorption (GSA): Incident excitation energy is deliberately chosen to be non-resonant with any ground-state absorption transitions within the lanthanide ions. This initial weak absorption, often assisted by phonon creation or annihilation, results in minimal direct population of the intermediate excited state, rendering the material initially transparent to the excitation radiation [10] [9].

Resonant Excited-State Absorption (ESA): Ions that reach the intermediate excited state (B) can efficiently absorb incident photons through resonant ESA transitions to higher energy levels (C). This process requires that the ESA cross-section significantly exceeds the GSA cross-section, ideally by a factor of 10,000 or more [5] [9].

Cross-Relaxation (CR): The critical feedback mechanism occurs when an ion in a high-energy state (C) transfers part of its energy to a neighboring ground-state ion (A), resulting in both ions occupying the intermediate state (B). This energy-transfer process effectively doubles the population available for further ESA events, creating a self-perpetuating cycle [5] [10].

The combination of these processes establishes a nonlinear positive feedback system where a single initially excited ion can trigger a cascade that populates the intermediate state exponentially with each cycle of ESA and CR [5]. This chain reaction continues until the system reaches a steady-state population in the emitting level, resulting in the characteristic ultra-nonlinear emission.

Essential Material Systems and Host Considerations

The realization of efficient PA requires specific material properties that facilitate the delicate balance between GSA, ESA, and CR processes. Key considerations include:

Lanthanide Dopant Selection: Specific trivalent lanthanide ions with appropriate energy level structures enable the PA effect. Tm3+ ions excited at 1064 nm or 1450 nm represent a canonical system, where the 3H6→3H5 GSA is weak, while the 3F4→3F2,3 ESA is strong, creating ideal conditions for avalanching [5]. Nd3+ ions have also demonstrated PA-like behavior under 1064 nm excitation, particularly in low-phonon hosts [10] [7]. More recently, Ho3+ ions have been exploited for parallel PA pathways enabling multicolor nanoscopy [11].

Host Matrix Engineering: The host lattice profoundly influences PA efficiency through several critical parameters [9]:

Phonon Energy: Low-phonon-energy hosts (e.g., fluorides like NaYF4 with ~350 cm−1) minimize non-radiative losses and protect excited-state populations. Heavier halides (chlorides, bromides) offer even lower phonon energies but often suffer from poor chemical stability [9].

Lattice Structure and Composition: Crystalline field modifications through ion substitution (e.g., Y3+ with smaller Lu3+) can dramatically enhance nonlinearity by modifying local crystal fields without significantly altering phonon spectra [9].

Dopant Concentration Optimization: Relatively high dopant densities (typically 1-10%) are necessary to ensure sufficiently short interionic distances for efficient CR, yet must be balanced against concentration quenching effects [5] [9].

Core-Shell Architecture: Inert shell passivation (e.g., undoped NaYF4 shells) effectively suppresses surface quenching but requires precise control to prevent dopant interdiffusion that can degrade nonlinear performance [9].

Table 1: Representative Material Systems for Photon Avalanching

| Host Material | Dopant Ion(s) | Excitation Wavelength | Emission Wavelength | Reported Nonlinearity | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaYF4/NaLuF4 | Tm3+ | 1064 nm, 1450 nm | ~800 nm | >100th order | Low phonon energy, tunable nonlinearity via Lu3+ substitution [5] [9] |

| KPb2Cl5 | Nd3+ | 1064 nm | 800-1000 nm | >200th order | Low phonon energy, demonstrates intrinsic optical bistability [7] [6] |

| NdAl3(BO3)4 | Nd3+ | 1064 nm | 1100-1800 nm (downshifting) | PA-like | Exhibits PA-like downshifting emissions, thermal coupling [10] |

| Various fluoride hosts | Ho3+ | NIR wavelengths | Multiple visible bands | Parallel pathways | Enables multicolor nanoscopy via parallel avalanche channels [11] |

Characteristic Emission Properties and Quantitative Signatures

Hallmarks of Photon Avalanching

The unique dynamics of PA manifest through several distinctive experimental signatures that differentiate it from conventional upconversion mechanisms [9]:

Excitation-Power Threshold (Ith): PA exhibits a sharp, well-defined excitation intensity threshold below which emission is minimal, and above which luminescence intensity increases dramatically by several orders of magnitude. This threshold behavior results from the critical nature of the positive feedback loop, which requires sufficient pumping to sustain the cascading process [5] [9].

Extreme Nonlinearity: Above the threshold, emission intensity follows a highly nonlinear power dependence described by Iem ∝ (Iexc)^n, where n represents the nonlinearity coefficient. PA systems routinely demonstrate n values ranging from tens to exceeding 200, significantly surpassing conventional multiphoton processes [7] [9].

Prolonged Rise Times: The population buildup in PA systems exhibits characteristically slow rise times extending from milliseconds to hundreds of milliseconds, particularly near the threshold intensity. This "critical slowing down" reflects the iterative nature of the population cycling through the ESA-CR feedback loop [9].

S-Shaped Power Dependence: A sigmoidal relationship between input power and output emission intensity provides a distinctive fingerprint of PA, with the steepest slope region corresponding to the threshold intensity where the positive feedback becomes self-sustaining [5].

Table 2: Quantitative Characteristics of Photon Avalanching in Different Material Systems

| Characteristic | Typical Range | Measurement Significance | Dependence Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonlinearity coefficient (n) | 10 - >200 | Order of nonlinearity in Iem ∝ (Iexc)^n | Dopant concentration, host matrix, core-shell structure [7] [9] |

| Threshold intensity (Ith) | kW/cm² - MW/cm² (material dependent) | Minimum excitation for avalanching | Host phonon energy, surface passivation, temperature [5] [9] |

| Rise time | Milliseconds to hundreds of milliseconds | Characteristic slowing near threshold | Excitation power, dopant concentration, distance from threshold [9] |

| ESA/GSA cross-section ratio | >10,000 (ideal) | Measures resonance condition efficiency | Host crystal field, excitation wavelength [9] |

Intrinsic Optical Bistability in ANPs

A remarkable manifestation of PA's extreme nonlinearity is the emergence of intrinsic optical bistability (IOB), recently demonstrated in Nd3+-doped KPb2Cl5 nanoparticles [7] [6]. This phenomenon enables ANPs to function as nanoscale optical memory elements with potential applications in optical computing and information processing.

Nonthermal Bistability Mechanism: In Nd3+:KPb2Cl5 nanoparticles, IOB originates from suppressed nonradiative relaxation coupled with the positive feedback of photon avalanching, rather than thermal effects that dominated earlier observations of bistability [7]. The system exhibits hysteresis in its emission intensity, maintaining a high-emission ("on") state even when excitation power is reduced below the initial threshold, only switching off at a significantly lower power [6].

Optical Memory and Switching: The hysteresis loop enables ANPs to act as volatile memory elements, with the large separation between "on" and "off" threshold powers providing a robust operational window [6]. Dual-laser excitation further permits transistor-like optical switching, where a weak auxiliary beam controls the emission state triggered by a primary pump [7].

Theoretical Framework: Bistability arises mathematically from the nonlinear system dynamics, where for a range of input intensities (between switch-up and switch-down thresholds), two stable output states exist. The specific state occupied depends on the excitation history, creating the characteristic hysteresis loop [12].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Synthesis of ANPs

Representative Protocol: Nd3+-Doped KPb2Cl5 Nanoparticles The synthesis of 30-nanometer KPb2Cl5:Nd3+ nanoparticles demonstrating IOB follows a hydrothermal or solvothermal approach [6]:

Precursor Preparation: Stoichiometric amounts of KCl, PbCl2, and NdCl3 are dissolved in a mixed solvent system of deionized water and ethanol (typically 1:1 ratio) with constant stirring. Neodymium doping concentrations typically range from 1-10%.

Reaction Conditions: The precursor solution is transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 180-220°C for 12-48 hours. The reaction temperature and time critically influence particle size and crystallinity.

Purification and Passivation: After cooling, nanoparticles are collected by centrifugation, washed repeatedly with ethanol and deionized water, and optionally coated with an inert shell (undoped KPb2Cl5) via successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction (SILAR) to reduce surface quenching.

Characterization: Structural analysis via X-ray diffraction confirms phase purity, while transmission electron microscopy verifies size distribution and morphology. Elemental mapping ensures uniform dopant distribution [7] [6].

Optical Characterization of PA

Nonlinear Power Dependence Measurements:

Excitation Source: Continuous-wave (CW) lasers with wavelengths matching weak GSA transitions (e.g., 1064 nm for Tm3+ or Nd3+ systems) are used. Laser power is precisely controlled using neutral density filters or acousto-optic modulators.

Detection System: Emission is collected through appropriate long-pass filters to block excitation light, dispersed through a monochromator, and detected using a photomultiplier tube or sensitive CCD camera. Measurements must span several orders of magnitude in excitation power.

Data Analysis: Logarithmic plots of integrated emission intensity versus excitation power are fitted to identify the threshold power and nonlinear coefficient. The characteristic S-shaped curve confirms PA behavior [5] [9].

Time-Resolved Dynamics:

- Excitation: Modulated CW or pulsed lasers with pulse widths appropriate for measuring millisecond-scale dynamics.

- Detection: Time-correlated single-photon counting or digital oscilloscopes capture emission decay trajectories.

- Analysis: Rise times are extracted from exponential fits to the emission buildup, with particular attention to the power dependence near threshold where critical slowing occurs [9].

Bistability and Hysteresis Protocols:

- Power Cycling: Excitation intensity is systematically increased from zero to beyond the switch-up threshold, then decreased while monitoring emission intensity.

- Pulse Modulation: Variable laser pulsing parameters (duty cycle, repetition rate) probe hysteresis width tunability.

- Dual-Beam Switching: An auxiliary laser at a different wavelength (e.g., 808 nm for Nd3+ systems) controls the switching between bistable states [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for ANP Investigation

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Specific Examples | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lanthanide precursors | Dopant ion source | TmCl3, Nd(NO3)3·6H2O, NdCl3 | Purity (>99.9%), anhydrous forms preferred [10] [7] |

| Host matrix precursors | Nanoparticle host formation | YCl3, LuCl3, NaF, KCl, PbCl2 | Stoichiometric ratios, controlled reactivity [7] [9] |

| Solvents and ligands | Reaction media and surface stabilization | Oleic acid, 1-octadecene, ethylene glycol | Anhydrous conditions for fluoride synthesis [5] |

| Shell precursors | Core-shell structure formation | Yttrium and sodium precursors for NaYF4 shells | Precise layer-by-layer deposition [9] |

| Excitation sources | Optical characterization | CW lasers (1064 nm, 1450 nm) | Spectral purity, power stability, Gaussian beam profile [5] [10] |

| Detection instrumentation | Emission measurement | Monochromators, PMTs, superconducting detectors | High sensitivity for weak signals, IR capability [10] [9] |

Applications and Future Research Directions

Emerging Technological Applications

The extreme nonlinearity and unique emission characteristics of ANPs enable transformative applications across multiple domains:

Super-Resolution Nanoscopy: PA nanoparticles compress the point-spread function well below the diffraction limit, enabling sub-40-nm resolution on conventional confocal microscopes without complex optical architectures or computational reconstructions [9]. Recent demonstrations of modulated parallel photon avalanche in Ho3+ ions further enable multicolor nanoscopy, allowing simultaneous visualization of multiple cellular targets with unprecedented resolution [11].

Ultrasensitive Sensing: The threshold-activated nature of PA confers exquisite sensitivity to environmental perturbations. ANPs function as nanoscale sensors for temperature, pressure, and mechanical deformations with sensitivity improvements of several orders of magnitude over conventional probes [9]. The PA-like process in NdAl3(BO3)4 demonstrates particular promise for thermal sensing applications, where intrinsic heating can trigger the avalanche behavior [10].

Optical Memory and Computing: The intrinsic optical bistability demonstrated in Nd3+-doped KPb2Cl5 nanoparticles provides a foundation for nanoscale optical memory elements, optical transistors, and neuromorphic computing systems [7] [6]. The ability to program emission states based on excitation history enables memory functions analogous to electronic memristive devices, while hysteresis-based switching facilitates optical logic operations [9].

Biomedical Applications: PA nanoparticles offer exceptional brightness and photostability for bioimaging and biosensing. Their near-infrared excitation and emission profiles enable deep-tissue penetration with minimal autofluorescence and photodamage. The recent development of biocompatible ANPs with negligible cytotoxicity further supports their potential for live-cell imaging and therapeutic applications [11].

Current Challenges and Research Frontiers

Despite significant advances, several challenges remain in optimizing and deploying ANP technology:

Material Optimization: Balancing high dopant concentrations for efficient CR against concentration quenching effects requires precise synthetic control. Advanced core-shell architectures with spatially confined dopant distributions represent a promising approach [9].

Temporal Dynamics: The characteristically slow rise times of PA systems may limit applications requiring rapid switching. Materials engineering through host modification (e.g., Lu3+ substitution in NaYF4 hosts) has demonstrated reduced rise times to ~9 ms while maintaining high nonlinearity [9].

Integration Challenges: Incorporating ANPs into functional devices and biological systems requires robust surface functionalization strategies and compatibility with existing optical platforms. The development of standardized protocols for bioconjugation and device integration will accelerate technology transfer [11].

Theoretical Modeling: Precisely simulating PA dynamics necessitates advanced models that account for spatial energy diffusion and position-dependent population dynamics within nanocrystals, moving beyond traditional ordinary differential equation approaches [9].

Future research directions include the exploration of new lanthanide dopant combinations, advanced host materials with lower phonon energies, integration with optical cavities and metamaterials for enhanced performance, and the application of machine learning for inverse design of optimized ANP structures [9]. As these developments progress, photon avalanching nanoparticles are poised to enable unprecedented capabilities in nanoscale imaging, sensing, and information processing.

Intrinsic optical bistability (IOB) in nanoscale materials represents a cornerstone for developing all-optical computing and signal processing technologies. This whitepaper details the material composition, structural properties, and functional mechanisms of neodymium-doped potassium lead chloride (Nd³⁺:KPb₂Cl₅) nanocrystals, a system demonstrating robust IOB via the photon avalanching (PA) effect [13] [6]. Current photonic technologies are often constrained by the weak optical nonlinearities of available nanomaterials and their reliance on complex external cavities to achieve bistable behavior. The discovery of IOB in Nd³⁺:KPb₂Cl₅ nanocrystals establishes a new paradigm, as the bistability is an inherent material property originating from a non-thermal mechanism involving suppressed non-radiative relaxation and positive feedback loops [13]. This positions avalanching nanoparticles (ANPs) as fundamental building blocks for next-generation nanophotonic devices, including optical memory, switches, and transistors, where light directly manipulates light [13] [7].

Material Composition and Fundamental Properties

The unique optical properties of this material system arise from the specific combination of a low-phonon energy host crystal and the tailored energy level structure of the neodymium dopant ions.

Host Crystal: KPb₂Cl₅

The host matrix, potassium lead chloride (KPb₂Cl₅), is a crystalline material prized for its exceptional infrared optical characteristics. Its key properties are summarized in Table 1 [14] [15].

Table 1: Key Properties of KPb₂Cl₅ Host Crystal

| Property | Value/Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal Structure | Monoclinic [14] | Defines the lattice site for dopant ions. |

| Maximum Phonon Energy | ~203 cm⁻¹ [14] | Very low energy of lattice vibrations, crucial for suppressing non-radiative decay. |

| Transmission Range | Broad, from ultraviolet to mid-infrared [15] | Enables applications across a wide spectral range. |

| Hygroscopicity | Low [14] [15] | Allows for processing in air, enhancing practical fabrication. |

Dopant Ion: Neodymium (Nd³⁺)

Trivalent neodymium ions (Nd³⁺) are incorporated into the KPb₂Cl₅ lattice, substituting for lead (Pb²⁺) ions. The Nd³⁺ ions act as the active luminescent centers responsible for the photon avalanching process. The specific energy levels of Nd³⁺ within the low-phonon KPb₂Cl₅ environment are critical for enabling the cross-relaxation and energy transfer processes that underpin the avalanche effect [13].

Nanocrystal Synthesis

The synthesis of these functional nanoparticles is typically achieved via a colloidal chemistry approach, producing crystals with well-defined dimensions. The reported Nd³⁺:KPb₂Cl₅ nanoparticles for IOB studies had a size of approximately 30 nanometers [6]. This nanoscale dimension is vital for integrating these materials into compact photonic circuits and devices.

The Photon Avalanching Mechanism and Intrinsic Optical Bistability

The extreme nonlinearity and IOB observed in these nanocrystals are driven by the photon avalanching process, a complex cycle of energy transfer and excited state absorption.

The Photon Avalanching Cycle

Photon avalanching is an upconversion mechanism characterized by orders-of-magnitude higher nonlinearity than conventional processes. Its dynamics can be described as a cyclic process with positive feedback, illustrated in Figure 1 and detailed below [13]:

Figure 1: The photon avalanching mechanism in Nd³⁺:KPb₂Cl₅ nanocrystals.

- Weak Initial Absorption: The process begins with a very weak ground-state absorption (GSA) of a pump photon, populating an intermediate energy level.

- Energy Transfer and Excited State Absorption: Energy transfer (ET) from a nearby already-excited Nd³⁺ ion or direct absorption promotes an ion to a higher energy level. This ion then undergoes strong excited-state absorption (ESA) to reach an even higher energy state.

- Cross-Relaxation and Positive Feedback: The highly excited ion transfers part of its energy to a neighboring ground-state ion via a cross-relaxation (CR) process. This results in two ions occupying the intermediate excited state from which ESA can occur. This step is critical as it creates a positive feedback loop, exponentially increasing the population of the emitting state.

- Amplified Emission: The massive buildup of ions in the excited state leads to intense, upconverted luminescence output. This process results in optical nonlinearities exceeding 200th-order, meaning a tiny increase in pump power produces an enormous increase in output light [13].

Origin of Intrinsic Optical Bistability

In Nd³⁺:KPb₂Cl₅ nanocrystals, IOB emerges from the PA cycle coupled with suppressed non-radiative relaxation. The host's extremely low phonon energy (~203 cm⁻¹) drastically reduces the rate at which excited ions lose energy as heat to the crystal lattice [14]. This suppression is essential for maintaining the long-lived excited states required to sustain the positive feedback loop of the avalanche. The system exhibits two stable states for the same input laser power, contingent on its history, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Characteristics of Bistable States in Nd³⁺:KPb₂Cl₅ ANPs

| Property | "OFF" State (Non-Luminescent) | "ON" State (Brightly Luminescent) |

|---|---|---|

| Luminescence | Negligible | High intensity |

| Trigger | Laser power reduced below a lower threshold | Laser power raised above an upper threshold |

| Mechanism | PA cycle cannot be sustained; positive feedback breaks | PA cycle is initiated and self-sustains |

| Memory Effect | Remains OFF until powered above upper threshold | Remains ON until powered below lower threshold |

This hysteresis is the hallmark of bistability and enables the material to function as an optical memory element, where the "ON" and "OFF" states represent binary 1 and 0 [13] [6]. The switching contrast between these states is very high, and the transition is controlled purely by the excitation light, without any thermal mechanism [13].

Experimental Protocols and Characterization

To validate IOB and the PA phenomenon, a series of rigorous experiments are performed on synthesized Nd³⁺:KPb₂Cl₅ nanocrystals.

Key Experimental Workflow

The standard methodology for investigating these properties involves the integrated workflow shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Key experimental workflow for characterizing IOB in ANPs.

Detailed Methodologies

1. Hysteresis Loop Measurement

- Objective: To demonstrate the hallmark of bistability: history-dependent output.

- Protocol: A laser beam tuned to the avalanche excitation wavelength (e.g., ~1064 nm for Nd³⁺) is focused onto a sample of nanocrystals [13]. The laser power is systematically ramped up from zero to a maximum value and then ramped down to zero while the intensity of the upconverted emission (e.g., in the visible range) is recorded.

- Expected Outcome: A pronounced hysteresis loop is observed. The emission intensity follows one path during the power increase (turning ON at a specific threshold, PON) and a different path during the power decrease (turning OFF at a lower threshold, POFF). The width of this hysteresis can be tuned by modulating the pulse repetition rate of the excitation laser [13].

2. Dual-Laser Switching Experiments

- Objective: To demonstrate transistor-like optical gating, where one light beam controls another.

- Protocol: Two laser sources are used. A constant-power "gate" beam is set to an intermediate power level where the nanocrystal is bistable. A second, weaker "signal" beam is then introduced. The presence or absence of the gate beam determines whether the signal beam can be amplified or switched by the nanocrystal ensemble [13] [7].

- Expected Outcome: The system acts as an optical transistor. The strong gate beam switches the nanocrystals to their "ON" state, allowing the weak signal beam to trigger a bright output. Without the gate, the signal beam is too weak to switch the system on [13].

3. Quantifying Nonlinearity Order

- Objective: To measure the extreme nonlinearity of the photon avalanching process.

- Protocol: The power dependence of the upconverted emission intensity (Iout) is measured as a function of the pump laser power (Ipump). The data is plotted on a log-log scale. The slope (n) of the linear region of this plot, where Iout ∝ (Ipump)^n, gives the order of nonlinearity [13].

- Expected Outcome: For Nd³⁺:KPb₂Cl₅ ANPs, the nonlinearity order (n) has been measured to be greater than 200, far exceeding conventional multiphoton processes [13] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful research into these ANPs requires specific materials and instrumentation. Table 3 lists the essential components and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ANP Investigation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| KPb₂Cl₅ Host Precursors | Forms the low-phonon crystal matrix. | High-purity KCl and PbCl₂ are crucial to minimize non-radiative losses [14]. |

| Neodymium Dopant Source | Provides active optical centers. | Anhydrous NdCl₃ is typically used, handled in an inert atmosphere to prevent hydrolysis [14]. |

| Colloidal Synthesis Setup | Produces monodisperse nanocrystals. | Requires inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen glovebox) and controlled temperature [13]. |

| Tunable Pulsed Lasers | Excites the avalanche process. | Wavelength must match the specific GSA band of Nd³⁺ (e.g., ~1064 nm) [13]. |

| Cryostat System | Maintains low temperature. | Current IOB demonstration requires ~160 K; achieving room-temperature operation is a key research challenge [16]. |

| Spectrometer/APD | Detects upconverted luminescence. | Requires high sensitivity to measure low-light emission from single nanoparticles or ensembles [13]. |

The intrinsic optical bistability demonstrated in Nd³⁺:KPb₂Cl₅ nanocrystals marks a significant leap forward in the field of avalanching nanoparticles. This work provides the first clear demonstration of a non-thermal, purely all-optical bistability mechanism in a nanomaterial, moving beyond earlier assumptions that attributed such effects to laser-induced heating [6]. The material's composition is fundamental to its function: the low-phonon KPb₂Cl₅ host is critical for suppressing non-radiative decay, while the Nd³⁺ dopant provides the ideal energy level structure for sustaining the photon avalanching feedback loop.

This breakthrough paves the way for the development of genuine nanoscale optical devices, such as volatile optical memory (RAM) and optical transistors, that can be integrated into photonic circuits at a scale comparable to modern microelectronics [13] [6]. The ability to manipulate light with light at the nanoscale, with extreme nonlinearity and hysteresis, establishes a new platform for all-optical signal processing. Future research will undoubtedly focus on optimizing the material composition—potentially through alternative dopants or core-shell structures—to achieve the critical goal of room-temperature operation, thereby unlocking the full practical potential of intrinsic optical bistability in real-world photonic technologies [16].

Intrinsic optical bistability (IOB) represents a fundamental property in nonlinear optical materials wherein a system exhibits two stable optical output states for a single input condition, with the current state dependent on the excitation history. This memory effect creates a hysteresis loop in the system's input-output response, enabling applications in optical memory, switching, and computing. Recent breakthroughs have demonstrated IOB in nanoscale materials, particularly in photon avalanching nanoparticles (ANPs), which exhibit exceptional nonlinear optical properties and hysteresis between luminescent and non-luminescent states. This emergent behavior in ANPs stems from their unique physical mechanisms that differ substantially from conventional bistable systems, which typically relied on thermal effects or complex resonator geometries. The development of ANPs with IOB marks a critical advancement toward practical nanophotonic devices that can operate on size scales comparable to contemporary microelectronics [6] [7].

The investigation of photon avalanching at the nanoscale has unveiled unprecedented optical nonlinearities that enable this bistable behavior. ANPs composed of lanthanide-ion-doped inorganic matrices generate high-energy photons through a chain reaction of excited-state absorption and cross-relaxation processes under surprisingly low pumping power. This review examines the fundamental principles governing hysteresis in luminescent ANP systems, quantitative characterization methodologies, experimental protocols for their study, and emerging applications in photonic technology and biological research. Understanding and controlling these hysteretic phenomena provides the foundation for next-generation optical devices with enhanced functionality and miniaturization potential [5].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Hysteresis in Avalanching Nanoparticles

The Photon Avalanching Process

The hysteresis behavior observed in ANPs originates from the photon avalanching mechanism, an upconversion process characterized by extreme nonlinearity and positive feedback. This process occurs in lanthanide-doped nanoparticles when excited with laser light at wavelengths that are only weakly absorbed from the ground state but strongly absorbed from excited states. The avalanching mechanism comprises three fundamental processes that create a self-sustaining cycle: weak ground-state absorption (GSA), excited-state absorption (ESA), and cross-relaxation (CR) energy transfer between neighboring ions [5].

The hysteretic behavior emerges from the interplay between these processes, which establishes a positive feedback loop capable of maintaining two distinct metastable states under identical excitation conditions. When the system resides in the "off" state, minimal luminescence occurs because most ions remain in the ground state, with only weak direct excitation. Transition to the "on" state requires a temporary increase in excitation power to initiate the avalanching process, after which the system can maintain this highly luminescent state even when power is reduced below the initial switching threshold. This path dependence creates the characteristic hysteresis loop that defines the system's bistable behavior and provides its memory functionality [6] [7].

Table 1: Key Processes in Photon Avalanching Hysteresis

| Process | Description | Role in Hysteresis |

|---|---|---|

| Ground-State Absorption (GSA) | Weak initial absorption of pump photons | Determines threshold sensitivity and off-state stability |

| Excited-State Absorption (ESA) | Strong absorption from excited states | Creates nonlinear response and enables state switching |

| Cross-Relaxation (CR) | Energy transfer between neighboring ions | Establishes positive feedback loop for bistability |

| Nonradiative Relaxation | Energy loss through phonon emissions | Suppressed in IOB to maintain excited state population |

Energy Transfer Dynamics and Bistability

The hysteresis loop in ANPs is fundamentally governed by energy transfer dynamics that create a bifurcation in the system's response to optical excitation. In Nd³⁺-doped KPb₂Cl₅ nanoparticles, IOB originates from suppressed nonradiative relaxation in Nd³⁺ ions combined with the positive feedback of photon avalanching. This combination produces extraordinary optical nonlinearities exceeding 200th-order, far surpassing conventional nonlinear optical materials. The specific electronic structure of the lanthanide ions enables this behavior, particularly when the excitation radiation is resonant with ESA transitions but not with ground-state transitions, creating an ideal scenario for avalanching [6] [7].

The critical slowing down of rise times represents another characteristic feature of photon avalanching systems contributing to hysteretic behavior. The rise time of the excited state population frequently extends well beyond the intermediate state's lifetime, creating a temporal delay that reinforces the bistable response. This delayed response, combined with the extreme ratio of ESA to GSA cross-sections (ideally exceeding 10⁴), enables the system to maintain distinct on and off states under intermediate excitation powers. The dopant ion concentration plays a crucial role in optimizing these dynamics, as it controls the average distance between ions and thus the efficiency of the cross-relaxation processes that drive the avalanching mechanism [5].

Quantitative Characterization of Hysteresis Parameters

Hysteresis Loop Measurements

The experimental characterization of hysteresis in ANPs involves measuring luminescence intensity as a function of excitation power through both increasing and decreasing power sweeps. Research on Nd³⁺-doped KPb₂Cl₅ nanoparticles has demonstrated high-contrast switching between luminescent and non-luminescent states with a pronounced hysteresis loop. The threshold power for switching from the off to on state (Pₒₙ) typically exceeds the power required to maintain the on state (Pₒff), creating the characteristic hysteresis window where both states are stable. This large difference between threshold powers enables the nanoparticles to function as nanoscale optical memory elements, particularly volatile random-access memory (RAM), as they can maintain their state under intermediate laser powers without continuous refreshing [6].

The modulation of laser pulsing parameters provides a powerful tool for tuning hysteresis widths in ANP systems. Studies have demonstrated that varying pulse duration and repetition rate can control the breadth of the bistable region, offering programmable hysteresis for different application requirements. Furthermore, dual-laser excitation schemes enable transistor-like optical switching, where a control beam modulates the response to a signal beam, creating opportunities for optical logic and amplification. These control mechanisms highlight the versatility of ANP-based bistable systems beyond simple binary memory applications [7].

Table 2: Quantitative Hysteresis Parameters in Avalanching Nanoparticles

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| On-Threshold Power | Pₒₙ | Material-dependent | Minimum power to switch from off to on state |

| Off-Threshold Power | Pₒff | < Pₒₙ | Power below which system returns to off state |

| Hysteresis Width | ΔP = Pₒₙ - Pₒff | Tunable via laser parameters | Determines bistability operating range |

| Luminescence Contrast Ratio | Iₒₙ/Iₒff | > 1000:1 | Distinguishability between states |

| Nonlinearity Order | n | > 200 | Extreme nonlinearity enabling bistability |

| Response Time | τᵣᵢsₑ | > intermediate state lifetime | Critical slowing down characteristic |

Material Composition and Performance Metrics

The specific material composition of ANPs profoundly influences their hysteresis characteristics and overall performance. Research has identified that 30-nanometer nanoparticles of potassium lead chloride doped with neodymium (KPb₂Cl₅:Nd³⁺) provide an optimal platform for IOB, combining suppressed non-radiative relaxation with efficient photon avalanching. The host matrix plays a critical role in minimizing non-radiative decay pathways, thereby enhancing the excited-state lifetimes necessary for sustaining the avalanching process. The choice of dopant ions, typically lanthanides such as Tm³⁺, Er³⁺, Ho³⁺, or Nd³⁺, determines the specific energy transitions available for the GSA, ESA, and CR processes that drive the avalanching mechanism [6] [5].

The size distribution and crystallographic quality of ANPs represent additional critical factors influencing hysteresis behavior. Nanoparticles with narrow size distributions and high crystalline perfection exhibit more uniform switching thresholds and sharper hysteresis transitions. Synthesis methods that optimize these material characteristics enable more predictable and reproducible bistable performance essential for device applications. Advanced characterization techniques, including temperature-dependent luminescence spectroscopy and time-resolved measurements, provide insights into the underlying mechanisms and quantitative parameters governing the hysteretic response of ANP systems [6] [17].

Experimental Protocols for Hysteresis Characterization

Nanoparticle Synthesis and Preparation

The synthesis of high-quality ANPs with well-defined hysteretic properties requires precise control over material composition, crystal structure, and morphological characteristics. For Nd³⁺-doped KPb₂Cl₅ nanoparticles, researchers have developed specialized protocols to achieve the necessary standards:

Precursor Preparation: Combine high-purity potassium chloride (KCl), lead chloride (PbCl₂), and neodymium chloride (NdCl₃) in stoichiometric ratios with careful control of dopant concentration (typically 1-5% Nd³⁺) to optimize cross-relaxation efficiency while minimizing concentration quenching effects [6].

Thermal Processing: Execute a multi-stage heating protocol under inert atmosphere conditions, beginning with gradual ramp-up to 400°C to remove solvents and organic residues, followed by sustained annealing at 500-600°C for 2-4 hours to promote crystal growth and Nd³⁺ incorporation into the host lattice [6] [17].

Size Selection and Purification: Implement centrifugal separation techniques to isolate nanoparticles with narrow size distribution centered at approximately 30 nanometers, followed by repeated washing with anhydrous solvents to remove unreacted precursors and byproducts that could interfere with optical properties [6].

Surface Functionalization: Apply appropriate ligand chemistry to enhance colloidal stability in various environments and prevent nanoparticle aggregation that could alter avalanching behavior through inter-particle energy transfer [5].

For lanthanide sesquioxides such as Yb₂O₃ and Er₂O₃, a modified co-precipitation method has been successfully employed, resulting in nanoparticles with narrow size distributions (52-60 nm) and homogeneous phases essential for reproducible hysteretic behavior [17].

Optical Characterization Setup

The experimental configuration for quantifying hysteresis loops in ANPs requires precise control of excitation conditions and sensitive detection capabilities:

Excitation Source: Utilize continuous-wave (CW) or pulsed laser systems with wavelength selection matched to weak ground-state absorption transitions of the specific ANP composition (e.g., 1064 nm for Tm³⁺-based ANPs, 808 nm for Nd³⁺-based ANPs). Incorporate variable optical attenuators for precise power control across multiple orders of magnitude [5] [7].

Microscopy Integration: Implement confocal or wide-field microscopy systems to enable single-particle investigations, utilizing high-numerical-aperture objectives (>NA 0.8) to maximize excitation efficiency and emission collection from individual nanoparticles [6] [5].

Detection Apparatus: Employ avalanche photodiodes (APDs) or photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) with appropriate spectral filtering to isolate the avalanche emission signal from excitation background, enabling quantitative intensity measurements with single-photon sensitivity where necessary [7].

Temporal Resolution: Incorporate time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) electronics for luminescence lifetime measurements, which provide critical insights into excited-state dynamics and avalanche buildup processes characteristic of hysteretic systems [5].

Environmental Control: Maintain constant temperature conditions through stage-mounted heating/cooling systems, as photon avalanching exhibits significant temperature sensitivity that could otherwise obscure hysteresis measurements [5] [17].

Hysteresis Loop Measurement Protocol

The precise quantification of hysteresis behavior in ANPs follows a systematic experimental procedure:

System Calibration: Characterize laser power stability and spatial profile before measurements. Confirm detector linearity across the expected intensity range using reference standards. Verify spectral filtering efficiency to eliminate excitation light from emission detection channels [6] [7].

Forward Power Scan: Gradually increase excitation power from minimal levels while continuously monitoring luminescence intensity. Use small power increments (typically 1-5% of expected threshold) near anticipated switching points to accurately determine the on-threshold power (Pₒₙ). Maintain constant integration times and environmental conditions throughout the measurement series [7].

Reverse Power Scan: After reaching maximum power, systematically decrease excitation power while continuing luminescence monitoring. Document the power level at which the system switches from the high-luminescence to low-luminescence state (Pₒff), noting any hysteresis in the transition points [6] [7].

Temporal Dynamics Assessment: At fixed power levels within the bistable region, measure luminescence rise and decay times to characterize critical slowing down effects. These measurements provide insights into the stability of each state and switching kinetics between them [5].

State Stability Testing: At intermediate power levels where bistability occurs, verify that both states can be maintained for extended periods (seconds to minutes) without spontaneous switching, confirming true bistability rather than transient effects [6].

Triggering Experiments: Demonstrate external control over state switching using secondary optical inputs at power levels within the bistable region, validating potential memory and logic functionality [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for ANP Hysteresis Studies

Table 3: Essential Materials for Avalanching Nanoparticle Research

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| KPb₂Cl₅:Nd³⁺ Nanoparticles | Primary bistable element | 30nm size optimal for IOB; Nd³⁺ concentration 1-5% |

| High-Purity Lanthanide Salts | Dopant precursors | Anhydrous chlorides or nitrates (>99.9%) |

| Inert Atmosphere Chamber | Synthesis environment | Prevents oxide formation and moisture degradation |

| CW NIR Laser Systems | Excitation source | Wavelength matched to weak GSA (e.g., 808nm, 1064nm) |

| Avalanche Photodiodes | Emission detection | Single-photon sensitivity for low-intensity measurements |

| Spectrofluorometer | Spectral characterization | Resolves emission bands and verifies avalanche emission |

| Temperature Control Stage | Environmental control | Minimizes thermal effects on avalanching threshold |

Applications and Future Directions

The demonstration of intrinsic optical bistability in photon avalanching nanoparticles opens transformative possibilities for photonic technology and biomedical applications. In optical memory and computing, ANPs provide a pathway to nanoscale optical memory elements and transistors that operate using light rather than electricity, potentially enabling smaller, faster components for next-generation computers. The hysteresis behavior essential for binary information storage occurs at unprecedented size scales, compatible with contemporary microelectronics manufacturing [6] [7].

In biological imaging and sensing, ANPs offer exceptional capabilities for super-resolution microscopy and deep-tissue imaging. Their nonlinear response enables techniques such as stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy without the complex laser systems typically required, while their near-infrared excitation and emission profiles facilitate deep tissue penetration with minimal scattering and autofluorescence. The hysteretic properties of ANPs can be leveraged for luminescence thermometry with exceptional sensitivity, as the avalanching process exhibits strong temperature dependence that shifts the hysteresis characteristics [5].

Future research directions focus on expanding the library of materials exhibiting IOB, optimizing hysteresis parameters for specific applications, and integrating ANP elements into functional photonic circuits. Challenges remain in achieving room-temperature operation for certain material systems, enhancing quantum yields, and developing scalable manufacturing approaches for ANP-based devices. As these fundamental hurdles are addressed, intrinsic optical bistability in avalanching nanoparticles is poised to enable revolutionary advances across information technology, biomedical research, and photonic computing [6] [5] [7].

Optical bistability describes a nonlinear optical phenomenon where a system exhibits two stable output states for a single input value over a specific input range, creating a characteristic hysteresis loop [18]. This behavior is fundamental for all-optical switching, memory, and logic devices, as it allows light to control light without intermediary electronic conversion [19]. Traditionally, this functionality has been achieved using conventional optical bistability (OB) mechanisms, which rely on external components like optical resonators to provide the necessary feedback [18]. In contrast, Intrinsic Optical Bistability (IOB) is a more recent and distinct phenomenon where the bistable behavior originates from the inherent properties of the material itself, requiring no external resonant structures [6] [13].

The discovery of IOB in certain nanomaterials represents a paradigm shift, offering a path to miniaturize optical computing components down to the nanoscale [8]. This technical guide provides a detailed comparison between these two mechanisms, with a specific focus on the groundbreaking context of Intrinsic Optical Bistability in Avalanching Nanoparticles (ANPs). It aims to equip researchers and scientists with a clear understanding of the core physical principles, experimental methodologies, and distinctive advantages that IOB offers over conventional approaches.

Fundamental Operating Principles

Conventional Optical Bistability (OB)

Conventional OB is an extrinsic property engineered through a system's design. The canonical configuration involves placing a nonlinear optical medium inside an optical resonator, typically a Fabry-Perot interferometer [18] [20]. The bistability arises from the synergistic interaction between two elements: the intensity-dependent refractive index or absorption of the nonlinear medium and the feedback provided by the resonator.

- Dispersive Bistability: This is the most common mechanism. The intracavity light intensity alters the refractive index of the nonlinear medium (via the Kerr effect), which shifts the resonant frequency of the cavity. For a fixed input laser frequency, this shift can make the cavity resonant or anti-resonant, leading to high or low transmission states for the same input power [18].

- Absorptive Bistability: This relies on a saturable absorber within the cavity. At low input intensities, the absorption is high, keeping the cavity in a low-transmission state. As intensity increases, the absorber saturates (bleaches), reducing absorption and switching the cavity to a high-transmission state [18].

The feedback is provided externally by the mirrors of the resonator, which trap the light, allowing it to interact multiple times with the nonlinear medium and build up the nonlinear effect. A system is considered optically bistable when it displays two possible output intensities (IT) for a single input intensity (II) within a certain range, forming a hysteresis loop [18].

Intrinsic Optical Bistability (IOB) in Avalanching Nanoparticles

IOB is an inherent property of specific materials, meaning the bistability does not require an external cavity. Recent pioneering research has demonstrated IOB in neodymium-doped potassium lead chloride (Nd³⁺:KPb₂Cl₅) avalanching nanoparticles [6] [13]. The mechanism is governed by a positive feedback loop within the nanomaterial itself, centered on the phenomenon of photon avalanching [13].

- Photon Avalanching: This is a highly nonlinear upconversion process. It involves the efficient, cross-relaxation-mediated energy transfer between neighboring Nd³⁺ ions within the crystal lattice. This process creates a positive feedback cycle where one excited ion can promote the excitation of multiple others, leading to an extreme nonlinearity where luminescence intensity scales with incident laser power to an order exceeding 200 [6] [13].

- The IOB Mechanism: The bistability originates from the competition between two processes: the positive feedback of photon avalanching and suppressed non-radiative relaxation [13]. The system has two metastable states: a "dark" state with low emissivity and a "bright" state with intense luminescence. The transition between these states is history-dependent, leading to a hysteresis curve in the input-output relationship.

- Non-Thermal Origin: Unlike some earlier presumed nanoscale bistability, the IOB in these ANPs is primarily electronic in nature, not thermal, making it faster and more efficient [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Operating Principles

| Feature | Conventional OB | IOB in ANPs |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Nature | Extrinsic, system-level property | Intrinsic, material-level property |

| Primary Requirement | External optical resonator (e.g., Fabry-Perot) | Photon avalanching mechanism within the material |

| Core Mechanism | Intensity-dependent refractive index/absorption combined with resonator feedback | Positive feedback from cross-relaxation and energy transfer between ions |

| Nonlinearity Order | Typically third-order (χ⁽³⁾) [18] | Extreme, >200th-order [13] |

| Primary Feedback Source | Mirrors of the external cavity | Internal energy migration between dopant ions |

| Typical Physical Scale | Macroscopic to microscopic (resonator size) | Nanoscale (single particle) |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Synthesis and Characterization of IOB ANPs

The following protocol is adapted from the work of Skripka et al. on Nd³⁺:KPb₂Cl₅ nanocrystals [13] [21].

Nanocrystal Synthesis:

- Method: Hot-injection colloidal synthesis is employed to achieve high-quality, monodisperse nanocrystals.

- Procedure: A lead precursor (e.g., lead oleate) is dissolved in a mixture of organic solvents and ligands (e.g., oleylamine) at elevated temperature (e.g., 150-180 °C). A solution containing potassium and neodymium chlorides is swiftly injected. The reaction proceeds for several minutes to hours to control crystal growth.

- Doping: Neodymium ions (Nd³⁺) are incorporated as guest dopants into the host KPb₂Cl₅ lattice during crystal growth. The host is chosen for its low phonon energy, which suppresses non-radiative decay and enhances luminescence efficiency [13].

Structural and Optical Characterization:

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Used to determine nanoparticle size, morphology, and monodispersity. The studied ANPs were approximately 30 nm in diameter [6].

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Confirms the crystalline phase and successful incorporation of Nd³⁺ ions into the host lattice without secondary phases.

- Spectroscopic Analysis: Photoluminescence (PL) excitation and emission spectroscopy are used to identify energy levels and confirm the photon avalanche behavior by measuring the nonlinear power dependence of the upconverted emission.

Protocol for Measuring IOB Hysteresis

This experiment directly demonstrates the bistable switching of a single ANP or an ensemble.

Setup: A confocal microscope is coupled with a tunable-wavelength continuous-wave (CW) or pulsed laser source. The laser is focused to a diffraction-limited spot onto a dilute sample of ANPs. The emitted luminescence is collected through the same objective, filtered from the excitation light, and detected by a sensitive photodetector (e.g., an avalanche photodiode or PMT) [13].

Hysteresis Loop Measurement:

- The excitation laser wavelength is fixed to resonate with a specific transition in the Nd³⁺ ion cycle (e.g., around 1064 nm for the avalanche process).

- The laser power is modulated in a triangular wave pattern, gradually increasing and then decreasing over time.

- For each input laser power, the output luminescence intensity from the ANP is recorded.

- Observation: As power increases from a low level, the ANP remains in a "dark" state until a specific switch-on threshold (P_ON) is reached, whereupon luminescence abruptly jumps to a high "bright" state. As power is decreased, the ANP remains bright well below PON, only switching off at a much lower switch-off threshold (POFF). This creates a clear hysteresis loop in a plot of Output Luminescence vs. Input Laser Power [13] [21].

Optical Switching and Logic Demonstration:

- Transistor-like Action: A two-laser experiment can be performed. A powerful "pump" beam is used to switch the ANP to its "on" state. A much weaker "gate" or "probe" beam can then be used to read the state or, by toggling the pump, to modulate the probe beam with high gain, mimicking a transistor [13].

- Memory Function: The ability of the ANP to remain in its "on" state at a low power between POFF and PON demonstrates its potential as a volatile optical memory element (similar to RAM) [6].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for IOB ANP Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function and Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Potassium Lead Chloride (KPb₂Cl₅) Host | A low-phonon energy crystal lattice that serves as the matrix for dopant ions, minimizing non-radiative energy loss. |

| Neodymium Ions (Nd³⁺) | The active dopant ions that provide the required energy levels for the photon avalanching process and generate the bistable luminescence. |

| Oleylamine / Lead Oleate | Surface ligands and precursors used in the colloidal synthesis to control nanocrystal growth, stability, and dispersibility. |

| Tunable CW (1064 nm) Laser | The excitation source tuned to the specific wavelength that resonantly drives the photon avalanche cycle in the Nd³⁺ ions. |

| Confocal Microscope | Essential apparatus for isolating and probing individual avalanching nanoparticles, enabling single-particle-level studies. |

Critical Differentiators: A Comparative Analysis

The distinctions between IOB and conventional OB extend beyond their fundamental principles, impacting their performance, scalability, and potential applications.

Performance and Physical Characteristics

- Feedback Mechanism: This is the most fundamental differentiator. Conventional OB relies on external optical feedback (mirrors), whereas IOB leverages internal electronic feedback from energy transfer processes [18] [13].

- Nonlinearity and Switching Threshold: Conventional OB typically exhibits a third-order nonlinearity (χ⁽³⁾). In stark contrast, IOB in ANPs demonstrates an extreme, >200th-order optical nonlinearity, enabling vastly higher sensitivity to input power changes and much lower energy switching once the system is in the "on" state [13] [21].

- Physical Scale and Integration: Conventional OB devices are limited by the diffraction limit of light and the physical size of the resonator. IOB operates at the nanoscale (∼30 nm particles), offering the potential for massive integration densities in photonic circuits [6] [8].

Operational Advantages and Challenges

- Power Consumption: The low-power switching maintenance of IOB ANPs after the initial turn-on is a significant advantage for energy-efficient computing. However, the initial switching threshold can be high [21].

- Fabrication and Robustness: Conventional OB systems require precise fabrication and alignment of optical components (mirrors, cavities). IOB ANPs are synthesized via chemical methods and are monolithic, eliminating alignment issues and offering greater mechanical robustness [18] [13].

- Speed: The non-thermal, electronic origin of IOB in ANPs suggests potential for ultra-fast switching speeds, potentially operating on picosecond timescales or faster, comparable to the fastest conventional all-optical switches [18] [6].

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Key Characteristics

| Characteristic | Conventional OB | IOB in ANPs |

|---|---|---|

| Feedback Mechanism | External (Optical Cavity) | Internal (Electronic Energy Transfer) |

| Typical Nonlinearity | Third-order (χ⁽³⁾) | >200th-order |

| Switching Energy | Moderate to High | Low (maintenance), High (initial switch-on) |

| Physical Footprint | Microscale to Macroscale | Nanoscale (∼30 nm) |

| Fabrication | Top-down (Etching, Lithography) | Bottom-up (Colloidal Synthesis) |

| Integration Potential | Moderate (bulk optics) to High (integrated photonics) | Very High (nanomaterial composites) |

| Switching Speed | Picoseconds to Nanoseconds (electronic) [18] | Potentially Ultra-fast (electronic mechanism) |

| Primary Contributor | System Engineering | Material Science & Chemistry |

The emergence of Intrinsic Optical Bistability in photon avalanching nanoparticles marks a significant leap forward. The key differentiator is the transition from engineered system-level bistability to inherent material-level bistability. This shift, powered by extreme internal nonlinearities and internal feedback, unlocks the potential for true nanoscale optical computing and memory components that are compatible with existing semiconductor fabrication processes, for example, via direct lithography [8].

For researchers in drug development and related life sciences, the implications, while more indirect, are profound. The advancement of IOB materials contributes to the broader field of optical computing, which promises to accelerate tasks like molecular docking simulations, genomic analysis, and complex system modeling by overcoming the bandwidth and power limitations of electronic processors. Furthermore, the deep understanding of energy transfer mechanisms in these ANPs could inspire new approaches to photodynamic therapy or bio-imaging.

Future research in IOB ANPs will focus on:

- Material Discovery: Identifying new host-dopant combinations to achieve room-temperature IOB at various wavelengths.

- Device Integration: Fabricating and testing prototype optical logic gates and memory cells using these nanomaterials.

- Speed Optimization: Precisely measuring and engineering the switching speed of IOB for practical computing applications.

- Advanced Actuation: Exploring electric field or other non-optical means to control the bistable state for greater device flexibility.

In conclusion, IOB is not merely an incremental improvement but a foundational change that addresses the critical challenges of size, power, and integration faced by conventional optical bistability, positioning it as a cornerstone for future photonic technologies.

Synthesis, Characterization and Practical Implementations of IOB-ANPs

The development of nanoscale materials exhibiting intrinsic optical bistability (IOB) represents a frontier in photonics and optical computing. IOB describes a phenomenon where a material can exist in one of two distinct optical states under identical excitation conditions, with the state determination dependent on the system's excitation history [13]. This bistable behavior enables fundamental optical operations such as switching and memory, which are crucial for developing computers that use light instead of electricity for information processing [1]. Until recently, IOB had primarily been observed in bulk materials unsuitable for microchip integration, limiting its practical applications [6]. The emergence of photon avalanching nanoparticles (ANPs), specifically neodymium-doped potassium lead chloride (Nd³⁺:KPb₂Cl₅) nanocrystals measuring approximately 30 nm, marks the first practical demonstration of IOB in nanoscale materials [1] [6].

These specialized nanoparticles exhibit extraordinary nonlinear optical properties, including >200th-order optical nonlinearities – the highest ever observed in any material [13] [6]. This extreme nonlinearity enables a unique switching behavior where the nanoparticles can transition abruptly between luminescent ("on") and non-luminescent ("off") states with minimal change in excitation power [22]. The fabrication of these 30-nm avalanching nanoparticles thus represents a critical advancement toward realizing optical computing components comparable in scale to contemporary microelectronics [1].

Synthesis and Fabrication of 30-nm Avalanching Nanoparticles

Bottom-Up Nanofabrication Approach

The synthesis of 30-nm Nd³⁺:KPb₂Cl₅ avalanching nanoparticles employs a bottom-up fabrication approach, which constructs nanostructures from atomic or molecular precursors rather than patterning bulk materials [23]. This methodology is particularly suited for creating complex nanoscale structures with precise control over composition and morphology. Bottom-up fabrication offers significant advantages for synthesizing doped nanocrystals, including better control over dopant distribution, reduced defect formation, and the ability to create complex structures that would be challenging to achieve through top-down methods [23].