Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles from Natural Materials: Sustainable Approaches for Advanced Drug Delivery

This comprehensive review explores the emerging field of green synthesis of nanoparticles using natural materials, focusing on its transformative potential for biomedical applications and drug delivery.

Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles from Natural Materials: Sustainable Approaches for Advanced Drug Delivery

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the emerging field of green synthesis of nanoparticles using natural materials, focusing on its transformative potential for biomedical applications and drug delivery. We examine the fundamental principles behind biologically-mediated nanoparticle formation using plant extracts, microorganisms, and biological compounds as eco-friendly alternatives to conventional methods. The article provides detailed methodological approaches for creating various nanoparticle types including metallic, polymeric, and lipid-based systems, with specific applications in drug encapsulation, targeted delivery, and cancer therapy. We address critical optimization parameters and troubleshooting strategies for controlling nanoparticle characteristics, while presenting rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses with traditional synthesis methods. This resource equips researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to implement sustainable nanotechnology approaches while addressing scalability and clinical translation challenges.

Principles and Potentials: Understanding Green Nanoparticle Synthesis

Green synthesis represents a fundamental paradigm shift in nanomaterial production, moving away from energy-intensive and environmentally harmful traditional methods toward biologically-mediated, sustainable approaches. This framework redefines nanoparticle fabrication by utilizing natural reducing, capping, and stabilizing agents derived from biological systems—including plants, bacteria, fungi, algae, and other biological entities—to transform metal precursors into functional nanoscale structures [1]. The core philosophy centers on implementing the principles of green chemistry throughout the synthesis process, eliminating or significantly reducing the use of hazardous substances, minimizing energy consumption, and ensuring environmental compatibility from inception to final product [2].

The transition to green synthesis methods addresses critical limitations of conventional chemical and physical approaches, which often require high temperatures and pressures, involve toxic reducing agents (e.g., sodium borohydride, hydrazine) and stabilizing chemicals, generate hazardous byproducts, and pose potential environmental and biological risks [3] [4]. In contrast, green synthesis leverages nature's inherent nanofabrication capabilities, utilizing the rich diversity of phytochemicals, proteins, enzymes, and other biological molecules that serve as both reducing agents and natural capping ligands, resulting in nanoparticles with enhanced biocompatibility and functionality for specialized applications [1] [2].

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Advantages

Core Defining Characteristics

Green synthesis of nanoparticles is distinguished by several foundational characteristics. Biological reduction utilizes metabolites from plants, fungi, bacteria, or algae as reducing agents instead of synthetic chemicals, converting metal ions to their zero-valent nanoscale forms through natural biochemical processes [1] [5]. Biological stabilization employs biomolecules that spontaneously adsorb to nanoparticle surfaces, preventing aggregation and controlling growth without additional synthetic capping agents [1] [2]. The approach maintains ambient synthesis conditions, typically proceeding efficiently at room temperature and atmospheric pressure, unlike many conventional methods that require extreme temperatures or pressures [1]. It also ensures renewable sourcing through the use of biologically renewable materials as feedstocks, aligning with circular economy principles [6]. Finally, it minimizes hazardous byproduct generation, significantly reducing or eliminating toxic waste streams associated with traditional nanoparticle synthesis [7] [3].

Quantitative Comparison of Synthesis Methods

Table 1: Comparative analysis of green versus chemical synthesis methods for metallic nanoparticles

| Parameter | Green Synthesis | Chemical Synthesis | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Temperature Conditions | Ambient to moderate (25-80°C) [1] | Often elevated (e.g., boiling for citrate method: 100°C) [4] | Turkevich citrate method requires boiling [4] |

| Reducing Agents | Plant phytochemicals (e.g., flavonoids, terpenoids), microbial enzymes [1] [7] | Sodium borohydride, hydrazine, citrate [4] | Neem leaf extract as reducing agent for AgNPs [7] |

| Capping/Stabilizing Agents | Natural biomolecules from extracts (proteins, polysaccharides) [1] | Synthetic polymers, surfactants (e.g., PVP, CTAB) [4] | Withania coagulans extract capping Mn-doped ZnO [3] |

| Particle Crystallite Size | Smaller sizes achievable (e.g., 9.7 nm for green AgNPs) [7] | Typically larger (e.g., 20.6 nm for chemical AgNPs) [7] | XRD analysis confirming size difference [7] |

| Colloidal Stability (Zeta Potential) | Higher stability (e.g., -55.2 mV for green AgNPs) [7] | Lower stability (e.g., -35.7 mV for chemical AgNPs) [7] | DLS measurements showing enhanced stability [7] |

| Environmental Impact | Lower toxicity, biodegradable byproducts [3] | Hazardous waste, toxic reagents [4] | Life cycle assessment studies [4] |

Table 2: Biological performance comparison of green versus chemically synthesized nanoparticles

| Performance Metric | Green-Synthesized NPs | Chemically-Synthesized NPs | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germination Rate Enhancement | +19% improvement over chemical AgNPs [7] | Baseline for comparison | Potato seed nanopriming [7] |

| Antioxidant Activity | Up to 43.13% higher [8] | Lower activity | Gold/silver NPs from H. sabdariffa [8] |

| Cytotoxicity | Negligible cytotoxicity, enhanced cell viability [8] | Significant cell death [8] | A549 and HFF cell lines [8] |

| Photocatalytic Efficiency | 53.8% dye degradation [3] | Variable, often lower | Methylene blue degradation [3] |

| Antibacterial Efficacy | Excellent against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria [3] | Requires higher concentrations | Mn-doped ZnO nanocomposites [3] |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Plant-Mediated Synthesis Protocol

Plant-mediated synthesis represents one of the most widely utilized green synthesis approaches due to its simplicity, scalability, and rich diversity of phytochemicals [1]. The standard experimental workflow involves several key stages. Plant selection and extract preparation begins with washing and drying plant materials (leaves, roots, fruits, or seeds) followed by grinding into fine powder. The material is then mixed with solvent (typically water or ethanol) and heated to 60-80°C for 10-30 minutes to extract bioactive compounds, after which the mixture is filtered to obtain a clear extract [3]. For the reaction mixture preparation, aqueous metal salt solutions (e.g., AgNO₃, HAuCl₄, Zn(CH₃CO₂)₂) are prepared at concentrations ranging from 1-10 mM, then mixed with plant extract in varying ratios (typically 1:1 to 1:10 v/v) [7] [3]. The synthesis reaction proceeds under continuous stirring at room temperature or mild heating (40-80°C), with reaction completion indicated by color change (e.g., colorless to brown for AgNPs, yellow to purple for AuNPs) over minutes to hours [7]. Finally, nanoparticle recovery involves centrifugation at high speeds (6,000-15,000 rpm) for 10-30 minutes to pellet nanoparticles, followed by washing with solvent to remove unreacted components, and drying at elevated temperatures (60-80°C) to obtain powdered nanoparticles [3].

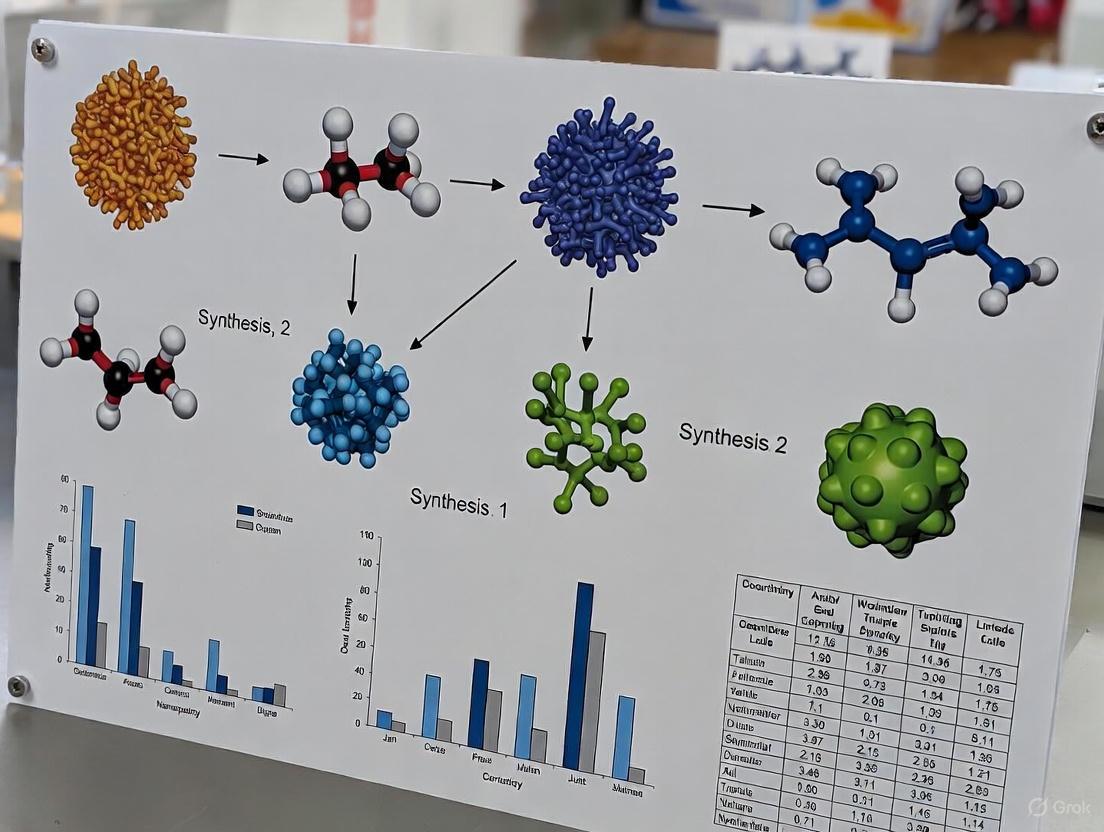

The following workflow diagram illustrates the plant-mediated green synthesis process:

Microbial Synthesis Protocol

Microbial synthesis utilizes bacteria, fungi, yeast, or microalgae for intracellular or extracellular nanoparticle production [1] [5]. The process begins with microbial cultivation, where selected microbial strains are cultured in appropriate growth media under optimized conditions to achieve sufficient biomass density [5]. For biomass preparation, cells are harvested through centrifugation and may be used directly as whole cells or resuspended in sterile water or buffer for reaction. In nanoparticle synthesis, the biomass suspension is exposed to metal salt solutions at specific concentrations, with reaction parameters such as pH, temperature, agitation, and reaction time carefully controlled and monitored [5]. Finally, nanoparticle recovery differs for extracellular synthesis (centrifugation of culture supernatant) versus intracellular synthesis (cell disruption followed by purification), with additional purification steps potentially including washing, filtration, and density gradient centrifugation [5].

Standard Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive characterization of green-synthesized nanoparticles employs multiple analytical techniques. UV-visible spectroscopy monitors surface plasmon resonance peaks during synthesis and determines optical properties and stability [7] [3]. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyzes crystalline structure, phase identification, and estimates crystallite size using Scherrer equation [7] [3]. Electron microscopy (SEM/TEM) provides direct imaging of nanoparticle size, shape, and morphology at nanoscale resolution [7]. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy identifies functional groups of biomolecules capping nanoparticle surfaces [7] [3]. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measures hydrodynamic size distribution and polydispersity index in solution [7]. Zeta potential analysis determines surface charge and predicts colloidal stability [7]. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) confirms elemental composition and purity [3].

Mechanistic Pathways in Green Synthesis

Molecular Reduction Mechanisms

The biological reduction of metal ions to nanoparticles in green synthesis systems proceeds through multiple simultaneous mechanistic pathways. Plant phytochemicals serve as both reducing and capping agents, where polyphenols, flavonoids, and terpenoids donate electrons to reduce metal ions while simultaneously stabilizing formed nanoparticles through surface coordination [1] [2]. In microbial systems, specific enzymes (e.g., nitrate reductases, dehydrogenases) catalyze metal ion reduction, often coupled with cellular detoxification pathways that sequester metals in nanoparticulate form [5]. Additionally, proteins and peptides present in biological extracts bind to metal ions through functional groups (-SH, -NH₂, -COOH), facilitating nucleation while controlling growth direction and preventing aggregation [2].

The reduction process can be conceptually understood through this mechanistic pathway:

Factors Influencing Nanoparticle Characteristics

Multiple parameters critically influence the properties of green-synthesized nanoparticles. pH variation significantly affects nanoparticle size and shape by altering the charge and reducing power of biological molecules [1]. Reaction temperature controls reduction kinetics and nucleation rates, with higher temperatures typically yielding smaller, more monodisperse particles [7]. Reaction time determines completion of reduction process and can influence crystallinity and stability [3]. Extract concentration affects the number of nucleation sites and capping density, directly impacting final particle size distribution [1] [7]. Metal ion concentration influences nucleation rates and determines the balance between nucleation and growth processes [7] [3]. Finally, incubation conditions (agitation, light exposure) can modify reaction kinetics and particle properties [2].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for green synthesis experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Plant Materials | Source of reducing and capping agents | Neem (Azadirachta indica) leaves [7], Withania coagulans fruits [3], H. sabdariffa flowers [8] |

| Metal Salts | Metal ion precursors for nanoparticles | Silver nitrate (AgNO₃) [7], Gold(III) chloride trihydrate (HAuCl₄·3H₂O) [8], Zinc acetate [3] |

| Solvents | Extraction medium and reaction solvent | Deionized water, ethanol, methanol (analytical grade) [3] |

| pH Modifiers | Optimization of reduction conditions | Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), hydrochloric acid (HCl) [3] |

| Culture Media | Microbial cultivation for biosynthesis | Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, nutrient broth, algal growth media [5] |

| Purification Aids | Separation and cleaning of nanoparticles | Centrifuges, filters (0.22 μm), dialysis membranes [7] [3] |

Applications and Performance Advantages

Agricultural Applications

Green-synthesized nanoparticles demonstrate remarkable efficacy in agricultural applications. As nanopriming agents, they enhance seed germination rates and stress resilience, with green-synthesized silver nanoparticles showing 19% improved germination over chemically-synthesized equivalents and 50% improvement over hydroprimed controls in potato seeds [7]. They also confer thermotolerance, maintaining 10% higher germination rates under elevated temperature stress (32.2°C) through enhanced water uptake capacity (82% increase in seed mass versus 44% in controls) [7]. Additionally, they provide disease resistance through inherent antimicrobial properties that protect seedlings from pathogenic infections [7] [3].

Biomedical Applications

In the biomedical domain, green-synthesized nanoparticles offer significant advantages. They exhibit enhanced biocompatibility, with studies showing negligible cytotoxicity in human cell lines (A549 and HFF) compared to chemically-synthesized nanoparticles that induce significant cell death [8]. Their antioxidant properties are substantially higher (up to 43.13% improvement) compared to chemically-synthesized equivalents, making them valuable for therapeutic applications [8]. They also demonstrate antimicrobial efficacy against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial strains, with green-synthesized Mn-doped ZnO nanocomposites showing excellent antibacterial activity [3]. Furthermore, they enable targeted cancer therapy through enhanced permeability and retention effects and functionalization capabilities, with microalgal nanoparticles showing promising results against various cancer cell lines [5].

Environmental Remediation

Green-synthesized nanoparticles effectively address environmental challenges through multiple mechanisms. They enable photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants, with Mn-doped ZnO nanocomposites demonstrating 53.8% degradation of methylene blue dye [3]. They also facilitate heavy metal removal from contaminated water through high surface area and functionalized surfaces that bind metal ions [1] [9]. Additionally, they provide antimicrobial water treatment using silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles for decentralized water purification systems [6].

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, green synthesis faces several challenges requiring attention. Standardization issues include batch-to-batch variability in biological sources due to seasonal, geographical, and cultivation variations that affect reproducibility [1] [4]. Scalability limitations involve transitioning from laboratory-scale synthesis to industrial production while maintaining consistent quality and properties [1] [2]. Characterization complexities arise from the biomolecular corona that forms around green-synthesized nanoparticles, complicating precise surface characterization [1]. There are also knowledge gaps regarding the exact mechanistic roles of specific biomolecules in reduction and capping processes [1] [2]. Finally, environmental impact assessments require more comprehensive life cycle analyses to quantitatively validate environmental benefits compared to conventional methods [4].

Future research directions should focus on developing standardized protocols for biological extract preparation and synthesis conditions to minimize variability [1]. Exploring novel biological sources, including extremophiles and agricultural waste products, could yield nanoparticles with unique properties [6] [5]. Integrating advanced technologies like machine learning and robotic automation could optimize synthesis parameters and accelerate discovery of novel green synthesis routes [6]. Engineering microalgae and other microorganisms through synthetic biology approaches could enhance nanoparticle yield and tailor properties for specific applications [5]. Finally, developing comprehensive regulatory frameworks and safety guidelines specifically addressing green-synthesized nanomaterials will be essential for clinical translation and commercial applications [4] [9].

Green synthesis represents a transformative approach to nanoparticle production that fundamentally redefines sustainable nanomaterial fabrication. By harnessing the sophisticated reduction and stabilization capabilities of biological systems, this methodology offers a viable alternative to traditional chemical methods, aligning nanotechnology development with green chemistry principles and circular economy objectives. The demonstrated advantages of green-synthesized nanoparticles—including enhanced biocompatibility, superior biological performance, and reduced environmental impact—position them as enabling technologies across biomedical, agricultural, and environmental applications. As research addresses current challenges in standardization, scalability, and mechanistic understanding, green synthesis is poised to transition from laboratory innovation to mainstream manufacturing, ultimately fulfilling its promise as a truly sustainable platform for advanced nanomaterial production.

The synthesis of nanoparticles (NPs) using natural resources represents a paradigm shift in nanotechnology, moving away from traditional chemical and physical methods that often involve toxic reagents and high energy consumption. Green synthesis leverages biological systems—including plants, microorganisms, and biomolecules—as sustainable factories to produce nanoparticles with controlled characteristics and reduced environmental impact [1]. This approach aligns with the principles of green chemistry and sustainable development, aiming to minimize hazardous waste and energy usage [10]. The inherent biochemical diversity in nature provides a vast toolkit for the reduction and stabilization of metal ions into nanoscale materials, offering a biocompatible and scalable alternative to conventional synthesis routes [11] [1].

The growing interest in biologically synthesized nanoparticles stems from their unique physicochemical properties and broad applicability across fields including biomedicine, agriculture, environmental remediation, and catalysis [12] [1] [10]. Unlike synthetically produced nanoparticles, biogenic nanoparticles often exhibit enhanced biocompatibility and functionalization potential due to the natural capping agents that facilitate their formation [11]. This technical guide explores the fundamental mechanisms, methodologies, and applications of nanoparticle production using plant extracts, microorganisms, and biomolecules, providing researchers with a comprehensive resource for designing green synthesis protocols.

Plant-Mediated Nanoparticle Synthesis

Mechanisms and Principles

Plant-mediated synthesis represents one of the most widely utilized approaches for green nanoparticle production due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and scalability [1]. This method utilizes aqueous extracts derived from various plant parts—including leaves, roots, fruits, and seeds—which serve as both reducing and stabilizing agents [1] [10]. The synthesis process is facilitated by diverse phytochemicals present in plant extracts, including flavonoids, phenols, alkaloids, terpenoids, and other secondary metabolites that possess redox capabilities [1] [13]. These compounds facilitate the reduction of metal ions to their zero-valent nanoscale forms while simultaneously stabilizing the surface to prevent aggregation [10].

The general procedure involves combining plant extract with a metal precursor solution under controlled conditions of temperature, pH, and agitation [1]. The rapid reduction of metal ions is often visually confirmed by color changes in the reaction mixture—for instance, the formation of a black solution when synthesizing iron nanoparticles [12] or a brownish-yellow solution for silver nanoparticles [13]. The concentration of phytochemicals, extraction method, and type of plant material significantly influence the nucleation, growth, and final characteristics of the nanoparticles [1]. However, a critical challenge in plant-based synthesis is the standardization of plant extracts, as variations in plant composition due to seasonality, geographical location, and cultivation practices can introduce inconsistencies in the synthesis process [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Iron Nanoparticle Synthesis Using Terminalia catappa Leaf Extract [12]:

- Plant Extract Preparation: Collect fresh leaves of Terminalia catappa, wash thoroughly, and air-dry at room temperature. Cut into small pieces and crush in distilled water. Boil the mixture at 70°C for 30 minutes, followed by filtration and centrifugation to remove debris. Store the supernatant as the final extract.

- Nanoparticle Synthesis: Prepare a 0.01 M solution of FeCl₃·6H₂O. Mix the leaf extract with the iron solution at a 1:1 ratio under constant stirring for 30 minutes. Observe color change to black, indicating nanoparticle formation.

- Purification and Recovery: Allow the mixture to stand for 3 hours, then centrifuge at 5000 rpm for 30 minutes. Collect the pellet and dry at 150°C for 2 hours before storage and characterization.

Protocol for Silver Nanoparticle Synthesis Using Cotula cinerea Extract [13]:

- Extract Preparation: Wash aerial parts of Cotula cinerea and prepare an aqueous extract through boiling in distilled water followed by filtration.

- Synthesis Process: Mix the plant extract with silver salt solution (concentration may vary). The reduction occurs rapidly at room temperature with continuous stirring.

- Characterization: Monitor synthesis using UV-Vis spectrophotometry with a characteristic peak observed at approximately 445 nm. Further characterization through XRD, SEM, and TEM confirms crystalline, spherical nanoparticles with sizes under 20 nm.

Table 1: Key Phytochemicals Involved in Plant-Mediated Nanoparticle Synthesis

| Phytochemical Class | Role in Synthesis | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | Reduction of metal ions, stabilization | Terminalia catappa, Cassia tora [12] |

| Phenolic compounds | Primary reducing agents, capping | Cotula cinerea [13] |

| Terpenoids | Stabilization of nanoparticles | Portulaca oleracea [12] |

| Alkaloids | Metal ion reduction | Tinospora cordifolia [12] |

| Polysaccharides | Template for nanoparticle formation | Various plant gums and exudates |

Diagram Title: Plant-Mediated Nanoparticle Synthesis Workflow

Microorganism-Assisted Nanoparticle Synthesis

Bacterial and Microbial Systems

Microorganisms offer a sophisticated biological platform for nanoparticle synthesis through both intracellular and extracellular mechanisms [1]. Among bacterial systems, magnetotactic bacteria represent a particularly remarkable example, producing highly structured magnetic nanoparticles through genetically controlled biomineralization processes [14]. Strains such as Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense MSR-1 produce chains of magnetite (Fe₃O₄) nanoparticles within specialized organelles called magnetosomes [14]. These structures are enveloped by biological membranes that provide natural functionalization sites for further modification [14].

The biosynthesis of magnetosomes is a complex process governed by specific genomic clusters within the bacterial genome [14]. It begins with iron capture from the environment, followed by precipitation into iron minerals within vesicles formed from the internal bacterial membrane [14]. The resulting nanoparticles exhibit exceptional characteristics including narrow size distribution, consistent particle shape, and high crystalline purity, typically ranging between 30-40 nm in diameter [14]. These uniform biogenic nanomagnets (BMNs) have demonstrated versatile applications in healthcare, environmental remediation, biosensing, and as hyperthermal agents for tumor inhibition [14].

Techno-Economic Analysis of Microbial Production

Scaling up microbial nanoparticle production presents both challenges and opportunities. A techno-economic analysis of magnetite production using Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense in a 29 m³ bioreactor demonstrated promising economic viability [14]. The simulated plant comprised three sections: an inoculum train, fermentation section, and downstream recovery section [14]. The fed-batch fermentation process operated at 30°C with controlled microaerophilic conditions (0.002-0.003 vvm oxygen supply) and pH range of 6.8-7.0 over 42 hours [14].

Table 2: Techno-Economic Analysis of Magnetosome Production [14]

| Parameter | Single-Stage Fed-Batch | Semicontinuous Process |

|---|---|---|

| Production cost (per kg) | US$ 10,372 | US$ 11,169 |

| Minimum selling price (per gram) | US$ 21-120 | US$ 21-120 |

| Bioreactor volume | 29 m³ | 29 m³ |

| Fermentation time | 42 hours | 42 hours |

| Temperature | 30°C | 30°C |

| Competitive advantage | Consistently below commercial synthetic nanoparticles | Comparable economic viability |

The economic assessment revealed fabrication costs of US$10,372 per kilogram for single-stage fed-batch and US$11,169 per kilogram for semicontinuous processes [14]. With minimum selling prices ranging between US$21-120 per gram—consistently below commercial values for synthetic nanoparticles—microbial production presents an economically competitive alternative for greener manufacturing of magnetic nanoparticles [14].

Biomolecule-Mediated Synthesis and Applications

Agricultural Applications

Green-synthesized nanoparticles show remarkable potential in agriculture as nanofertilizers to enhance crop productivity and mitigate abiotic stress [12] [11] [13]. Research on pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan) demonstrated that green-synthesized iron and zinc nanoparticles significantly improved seed germination, plant growth, and overall productivity [12]. Through optimized seed priming and foliar application, field trials recorded a 77.41% increase in seed yield (1728 kg ha⁻¹), a 77.35% higher stalk yield (4285 kg ha⁻¹), and a 52.20% increase in husk yield (828 kg ha⁻¹) compared to control groups [12]. Additionally, these treatments enhanced SPAD values (chlorophyll content) by 27.82% and NDVI values (vegetation index) by 54.38%, indicating improved plant health and photosynthetic efficiency [12].

In abiotic stress mitigation, silver nanoparticles synthesized using Cotula cinerea extract demonstrated efficacy in enhancing salt tolerance in durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf) [13]. Under saline conditions (150 mM NaCl), seeds treated with 40 mg L⁻¹ of AgNPs achieved 90% germinability compared to 70% in untreated controls [13]. Root length exhibited an 86% increase (7.28 cm vs. 3.9 cm in control), while root fresh weight increased from 0.04g to 0.06g under salt stress [13]. These findings underscore the potential of green-synthesized nanoparticles as effective tools for sustainable crop improvement in challenging environments.

Biomedical Applications

Green-synthesized metal nanoparticles (G-MNPs) have gained significant attention in biomedical fields due to their enhanced biocompatibility and functionalization potential [1]. Their intrinsic properties—including electronic, optical, and physicochemical characteristics coupled with surface plasmon resonance—make them highly tunable for various therapeutic applications [1]. These nanoparticles have demonstrated promising outcomes in targeted drug delivery, biosensing, photothermal and photodynamic therapies, medical imaging, and as antimicrobial agents [1] [10].

The biomedical applicability of green-synthesized nanoparticles stems from their unique advantages over chemically synthesized counterparts, including reduced toxicity, enhanced biodegradability, and the presence of natural capping agents that facilitate further functionalization [1]. Silver nanoparticles synthesized using plant extracts have shown particularly potent antimicrobial efficacy against multidrug-resistant pathogens, making them valuable candidates for combating antibiotic-resistant infections [10]. Additionally, their application in wound healing and tissue engineering demonstrates the versatility of biogenic nanoparticles in addressing diverse medical challenges [1].

Diagram Title: Applications of Green-Synthesized Nanoparticles

Characterization and Analytical Techniques

Comprehensive characterization is essential to confirm the synthesis, determine physicochemical properties, and validate the applicability of biogenic nanoparticles. Multiple analytical techniques provide complementary information about different aspects of the synthesized nanomaterials [12] [13].

UV-Visible Spectrophotometry serves as a preliminary characterization tool that confirms nanoparticle formation through surface plasmon resonance peaks at specific wavelengths—for instance, silver nanoparticles typically exhibit peaks between 400-450 nm [13]. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) measures the hydrodynamic diameter and size distribution of nanoparticles in suspension, while Zeta Potential analysis indicates surface charge and colloidal stability [12]. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) provide high-resolution imaging of nanoparticle morphology, size, and distribution at the nanoscale [12] [13]. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) analysis determines the crystalline structure, phase composition, and crystallite size of the nanomaterials [12]. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) identifies functional groups and biomolecules responsible for reduction and stabilization by analyzing characteristic vibrational frequencies [12].

Table 3: Standard Characterization Techniques for Biogenic Nanoparticles

| Technique | Information Obtained | Typical Results for Green NPs |

|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Surface plasmon resonance, synthesis confirmation | Peak at 445.91 nm for AgNPs [13] |

| Dynamic Light Scattering | Hydrodynamic size, size distribution | 351.6 nm for AgNPs (larger due to hydration) [13] |

| Zeta Potential | Surface charge, colloidal stability | High negative/positive values indicate stability |

| TEM | Morphology, actual particle size, distribution | Spherical particles, ~15.128 nm for AgNPs [13] |

| SEM | Surface morphology, particle shape | Spherical/cuboidal morphology [13] |

| XRD | Crystalline structure, phase identification | Face-centered cubic for AgNPs [13] |

| FTIR | Functional groups, capping agents | Presence of polyphenols, flavonoids [12] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Green Nanoparticle Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Plant extracts | Reducing and stabilizing agents | Terminalia catappa (iron NPs), Tridax procumbens (zinc NPs) [12] |

| Metal salts | Precursor materials | FeCl₃·6H₂O, Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, AgNO₃ (0.01-0.1 M) [12] [13] |

| Culture media | Microbial growth and NP production | Specific media for magnetotactic bacteria [14] |

| Centrifugation equipment | Nanoparticle recovery and purification | 5000 rpm for 30 minutes [12] |

| pH buffers | Reaction condition control | Maintain pH 6.8-7.0 for bacterial culture [14] |

| Temperature control systems | Optimization of synthesis conditions | 30°C for bacterial fermentation, 70-80°C for extract preparation [14] [12] |

| Filtration membranes | Extract clarification and sterilization | Whatman No. 1 filter paper [12] |

The utilization of natural resources for nanoparticle production represents a transformative approach that effectively bridges nanotechnology with sustainability principles. Plant extracts, microorganisms, and biomolecules offer diverse biological platforms for generating nanoparticles with tailored characteristics and enhanced biocompatibility. The sophisticated biochemical machinery within these biological systems facilitates the precise reduction and stabilization of metal ions into functional nanomaterials, often surpassing the capabilities of conventional synthetic methods. As research in this field advances, optimizing standardization protocols, scaling-up production processes, and conducting comprehensive toxicological assessments will be crucial for fully realizing the potential of biogenic nanoparticles across agricultural, biomedical, and environmental applications.

The green synthesis of nanoparticles represents a paradigm shift in nanotechnology, moving away from traditional chemical and physical methods that often involve hazardous substances, high energy consumption, and toxic byproducts [15] [16]. This eco-friendly approach leverages biological systems—including plants, bacteria, fungi, and algae—as sustainable factories for nanoparticle production [17]. The fundamental superiority of biogenic synthesis lies in its utilization of inherent biological compounds that serve dual roles as reducing and stabilizing agents, forming nanoparticles with enhanced biocompatibility and unique physicochemical properties [18]. Understanding the precise molecular mechanisms through which these biological entities facilitate reduction and stabilization is crucial for advancing green nanotechnology and harnessing its full potential in biomedical applications, drug delivery, and environmental remediation [15] [19].

The synthesis process is essentially a redox reaction where metal ions from precursor salts are reduced to their zero-valent metallic form, followed by nucleation and growth into nanostructures [20]. What distinguishes biogenic synthesis is that this process occurs under ambient conditions, powered by biological molecules rather than harsh chemicals [18]. The resulting nanoparticles are typically capped with biological compounds that impart stability and functionality, making them particularly valuable for biomedical applications where surface characteristics dictate biological interactions [21] [19]. This review comprehensively examines the molecular-level mechanisms underlying these processes, providing researchers with a technical foundation for advancing green nanomaterial design.

Molecular Mechanisms of Metal Ion Reduction

Reduction by Plant Phytochemicals

Plant-mediated synthesis represents the most widely utilized approach in green nanotechnology due to the rich diversity of phytochemicals that facilitate rapid reduction of metal ions [18]. The reduction process is primarily driven by secondary metabolites that possess redox-active functional groups.

Table 1: Key Phytochemical Classes Involved in Nanoparticle Reduction

| Phytochemical Class | Specific Examples | Reduction Mechanism | Metal Ions Reduced |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | Quercetin, Kaempferol, Catechin | Electron donation via phenolic OH groups, tautomerization | Ag⁺, Au³⁺, Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺ |

| Terpenoids | Monoterpenoids, Sesquiterpenoids, Diterpenoids | Carbonyl groups undergo tautomerization | Ag⁺, Au³⁺, Pt⁴⁺ |

| Phenolic Acids | Gallic acid, Caffeic acid, Ferulic acid | Oxidation of phenolic groups to quinones | Ag⁺, Au³⁺, Fe³⁺ |

| Alkaloids | Piperine, Caffeine, Theobromine | Tertiary amine oxidation | Ag⁺, Pd²⁺, Cu²⁺ |

| Proteins/Enzymes | NADH-dependent reductases, Catalases | Electron transfer via cofactors | Ag⁺, Au³⁺, Se⁴⁺ |

The reduction mechanism begins with the chelation of metal ions by phytochemicals through their functional groups. Flavonoids and phenolic compounds utilize their hydroxyl groups to coordinate metal ions, facilitating electron transfer from the phenol to the metal ion, thereby reducing the metal and oxidizing the phenol to a quinone [15]. Terpenoids employ their carbonyl groups, which undergo tautomerization to enol forms that donate electrons to metal ions [19]. The efficiency of reduction depends on parameters including pH, temperature, reactant concentrations, and reaction time, which must be optimized for each biological system [18].

Figure 1: Molecular Reduction Pathway for Plant-Mediated Nanoparticle Synthesis

Microbial Reduction Mechanisms

Microorganisms including bacteria, fungi, yeast, and algae employ specialized enzymatic machinery for nanoparticle synthesis, typically as part of detoxification pathways [15] [20]. The microbial reduction mechanisms can be categorized as either intracellular or extracellular processes.

Intracellular reduction involves the transport of metal ions across the cell membrane through membrane transporters or via passive diffusion. Once inside the cell, metal ions are reduced by intracellular enzymes such as NADH-dependent reductases [15]. For instance, Lactobacillus kimchicus demonstrates intracellular synthesis of gold nanoparticles through this mechanism [15]. The resulting nanoparticles are capped with intracellular proteins and peptides, which must then be extracted through cell disruption techniques.

Extracellular reduction occurs outside the microbial cell, where secreted enzymes or metabolic byproducts reduce metal ions. Bacteria such as Shewanella oneidensis secrete extracellular reductases that facilitate the synthesis of nearly monodispersed silver nanoparticles (2-10 nm) [20]. Similarly, the fungus Fusarium oxysporum secretes NADH-dependent nitrate reductases that reduce metal ions extracellularly [22]. This approach is advantageous for large-scale production as it avoids the need for cell disruption to harvest nanoparticles.

Yeast and algae utilize specialized metal-binding peptides called phytochelatins for both reduction and stabilization. These peptides, composed of glutamate, cysteine, and glycine, feature thiol groups that coordinate with metal ions and facilitate reduction through electron transfer [22]. In some photosynthetic algae, siderophores—special iron-chelating molecules—have been reported to mediate nanoparticle formation [22].

Stabilization Mechanisms of Biogenic Nanoparticles

The Role of Capping Agents in Nanoparticle Stability

Stabilization is critical for preventing nanoparticle aggregation and maintaining their nanoscale properties. Biogenic capping agents adsorb onto nanoparticle surfaces, creating a protective layer that provides steric hindrance and/or electrostatic repulsion [19]. These capping agents are inherently present in the biological extracts and spontaneously coordinate with the growing nanoparticles during synthesis.

Table 2: Biological Capping Agents and Their Stabilization Mechanisms

| Capping Agent Category | Specific Examples | Stabilization Mechanism | Functional Groups Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins | Collagen, BSA, HSA, Enzymes | Steric hindrance, Electrosteric stabilization | -NH₂, -COOH, -SH |

| Polysaccharides | Starch, Chitosan, Cellulose | Steric stabilization, Viscosity enhancement | -OH, -NH₂ |

| Lipids | Phospholipids, Fatty acids | Hydrophobic interactions, Bilayer formation | -COOH, Hydrocarbon chains |

| Phytochemicals | Flavonoids, Terpenoids, Alkaloids | Electrostatic, Coordination bonds | -OH, C=O, -NH |

| Nucleic Acids | DNA, RNA | Template-assisted, Sequence-specific binding | Phosphate, -NH₂, -OH |

The effectiveness of a capping agent depends on its binding affinity to the nanoparticle surface and its ability to create sufficient repulsive forces between particles. Proteins function as excellent capping agents due to the presence of multiple functional groups (amino, carboxyl, thiol) that can coordinate with metal surfaces [19]. For example, bovine serum albumin (BSA) provides electrosteric stabilization through a combination of electrostatic repulsion from charged amino acid residues and steric hindrance from the protein structure [19]. Similarly, collagen's triple-helical structure creates a stable matrix that controls nanoparticle size and prevents aggregation more effectively than chemical stabilizers like citrate [19].

Molecular Interactions in Biogenic Capping

At the molecular level, stabilization occurs through various interactions between capping agents and nanoparticle surfaces:

Coordination bonds form between metal atoms on the nanoparticle surface and electron-donating groups on biological molecules. Thiol groups (-SH) in cysteine-containing peptides and proteins exhibit particularly strong affinity for noble metal surfaces like gold and silver, forming stable metal-thiolate bonds [22]. Similarly, amine groups (-NH₂) from amino acids and proteins coordinate with metal surfaces through lone pair donation [19].

Electrostatic stabilization occurs when charged functional groups on capping agents create repulsive forces between nanoparticles. Carboxylate groups (-COO⁻) from organic acids and proteins impart negative charges that prevent aggregation through Coulombic repulsion [20]. The surface charge can be modulated by pH adjustment to enhance stability.

Steric stabilization is provided by large biomolecules like proteins and polysaccharides that create physical barriers between nanoparticles, preventing close approach and aggregation [19]. Polymers like starch and chitosan form hydrated layers around nanoparticles that must be disrupted for aggregation to occur.

In many cases, biogenic capping involves multiple stabilization mechanisms simultaneously. For example, serum albumin proteins provide both electrostatic and steric stabilization (electrosteric stabilization), making them particularly effective capping agents [19].

Experimental Protocols for Mechanistic Studies

Standardized Green Synthesis Methodology

To ensure reproducibility in biogenic nanoparticle synthesis, standardized protocols must be implemented with careful control of reaction parameters. The following represents a generalized procedure for plant-mediated synthesis:

Plant Extract Preparation:

- Select and authenticate plant material (leaves, roots, bark, etc.)

- Wash thoroughly with distilled water to remove surface contaminants

- Dry at 40°C in a hot air oven until crisp

- Pulverize using a laboratory blender to fine powder

- Prepare extract by mixing 10 g powder with 100 mL distilled water (1:10 ratio)

- Heat at 60-80°C for 10-15 minutes with continuous stirring

- Filter through Whatman No. 1 filter paper, followed by 0.45 μm membrane filtration

- Store extract at 4°C for maximum stability (use within one week)

Nanoparticle Synthesis:

- Prepare 1-10 mM aqueous solution of metal salt (e.g., AgNO₃, HAuCl₄, ZnSO₄)

- Mix plant extract with metal salt solution in specific ratio (typically 1:9 to 1:1 v/v)

- Adjust pH to optimal range (typically 6-10) using NaOH/HCl

- Incubate reaction mixture at specified temperature (25-80°C) with constant stirring

- Monitor color change visually and spectroscopically

- Continue reaction until completion (5 minutes to 24 hours depending on system)

- Purify nanoparticles by centrifugation (10,000-15,000 rpm for 15-30 minutes)

- Resuspend pellet in distilled water or buffer and repeat 2-3 times

- Characterize using spectroscopic and microscopic techniques

Critical Parameters for Optimization:

- Plant extract concentration and phytochemical composition

- Metal salt concentration and type

- Reaction temperature and pH

- Incubation time

- Mixing speed and efficiency

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Understanding the molecular mechanisms of reduction and stabilization requires sophisticated characterization approaches:

UV-Visible Spectroscopy: Monitors the formation of nanoparticles through surface plasmon resonance measurements, typically in the range of 400-450 nm for silver and 500-550 nm for gold nanoparticles [17]. Kinetics of nanoparticle formation can be tracked using time-dependent measurements.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Provides high-resolution imaging of nanoparticle size, shape, and distribution [23]. Sample preparation involves placing a drop of nanoparticle suspension on carbon-coated copper grids, followed by drying under vacuum. For biological samples, fixation with glutaraldehyde and staining with uranyl acetate may be required [23].

Energy-Filtered TEM (EFTEM): Distinguishes nanoparticles from cellular components through elemental mapping, particularly useful for intracellular localization studies [23].

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Identifies functional groups of capping agents on nanoparticle surfaces by detecting changes in absorption peaks before and after synthesis.

X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Determines crystallinity and crystal structure of nanoparticles through Bragg's law analysis [17].

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Measures hydrodynamic diameter and size distribution of nanoparticles in suspension [21].

Zeta Potential Analysis: Quantifies surface charge and predicts colloidal stability through electrophoretic mobility measurements.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biogenic Nanoparticle Research

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Primary Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts | AgNO₃, HAuCl₄·3H₂O, ZnSO₄·7H₂O, CuSO₄·5H₂O | Precursor for nanoparticle synthesis | High purity (>99%), light-sensitive, prepare fresh solutions |

| Biological Materials | Plant tissues, Microbial cultures, Purified biomolecules | Source of reducing/capping agents | Standardize growth conditions, extraction methods |

| Buffers | Phosphate, Acetate, Borate buffers | pH control during synthesis | Adjust to optimal pH for specific biological system |

| Centrifugation Equipment | Ultracentrifuge (up to 100,000×g) | Nanoparticle purification and separation | Optimize speed/time to prevent aggregation |

| Filtration Units | 0.22 μm, 0.45 μm membrane filters | Sterilization and purification | Pre-wet membranes to prevent adsorption |

| Spectrophotometer | UV-Vis with kinetic measurement capability | Synthesis monitoring and characterization | Use quartz cuvettes for accurate measurements |

| Microscopy Grids | Carbon-coated copper grids | TEM sample preparation | Plasma clean for improved adhesion |

Biomedical Applications and Functional Advantages

The biological capping agents in green-synthesized nanoparticles provide unique advantages for biomedical applications. In drug delivery, the inherent biocompatibility of biogenic capping reduces immunogenic responses and improves circulation time [21]. For instance, albumin-coated nanoparticles have demonstrated enhanced blood-brain barrier penetration, facilitating drug delivery to the central nervous system [21]. Transferrin-conjugated nanoparticles show significantly higher cellular uptake in brain endothelial cells compared to unconjugated counterparts, highlighting the targeting potential of biological capping [21].

In antimicrobial applications, biogenic silver nanoparticles capped with plant phytochemicals exhibit broad-spectrum activity against pathogenic bacteria, including antibiotic-resistant strains [20]. The capping layer itself can contribute to antibacterial efficacy through membrane disruption and reactive oxygen species generation [20]. Importantly, concentration windows exist where nanoparticles are toxic to bacteria but not mammalian cells, enabling therapeutic selectivity [20].

For wound healing applications, the combination of metallic nanoparticles with biological capping agents accelerates tissue regeneration through antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and pro-angiogenic effects [18]. Collagen-capped nanoparticles integrate naturally with the extracellular matrix, promoting cell migration and proliferation at wound sites [19].

The molecular mechanisms underlying biogenic nanoparticle synthesis involve sophisticated redox biochemistry and surface stabilization phenomena. Biological compounds reduce metal ions through electron donation from functional groups including phenols, carbonyls, and thiols, while stabilization is achieved through coordination bonds, electrostatic repulsion, and steric hindrance from capping agents. These natural synthesis pathways offer sustainable alternatives to conventional methods, producing nanoparticles with enhanced biocompatibility and biomedical functionality.

Despite significant advances, challenges remain in standardizing biological sources, scaling up production, and fully elucidating structure-activity relationships. Future research should focus on quantitative analysis of reaction kinetics, systematic evaluation of capping agent effects on biological activity, and detailed investigation of molecular-level interactions between capping agents and nanoparticle surfaces. As characterization techniques advance and our understanding of biological reduction mechanisms deepens, green synthesis promises to play an increasingly pivotal role in sustainable nanotechnology development across biomedical, environmental, and industrial sectors.

The green synthesis of nanoparticles represents a paradigm shift in nanotechnology, offering a sustainable alternative to conventional physical and chemical methods. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the three cornerstone advantages of green synthesis: enhanced sustainability through environmentally responsible production processes, significant cost-effectiveness from resource-efficient methodologies, and substantially reduced toxicity profiles for biomedical and environmental applications. Drawing upon recent advances in the field, we examine the mechanistic foundations of plant-based, microalgal, and other biological synthesis routes, detail standardized experimental protocols for reproducible nanoparticle fabrication, and present quantitative data comparing performance metrics across synthesis methods. The comprehensive data presented herein establishes green synthesis as a technologically viable and economically superior approach for research-scale and industrial nanoparticle production, aligning with global sustainability initiatives while maintaining rigorous performance standards required by pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries.

Green synthesis of nanoparticles utilizes biological resources—including plant extracts, microorganisms, algae, and other biomaterials—as sustainable alternatives to conventional chemical and physical synthesis methods [16]. This approach operates at the intersection of green chemistry and nanotechnology, emphasizing the design of safer chemical products and processes that reduce or avoid the formation and application of hazardous substances [24]. Where traditional nanoparticle synthesis relies on toxic chemicals, high energy inputs, and generates hazardous byproducts, green synthesis employs biologically derived reducing and stabilizing agents under ambient conditions, representing a fundamental shift toward sustainable nanomaterial production [1].

The foundational principle of green synthesis centers on the use of biological metabolites as nanoreactors, where phytochemicals, proteins, enzymes, and other biocompounds facilitate the reduction of metal ions to their nanoscale counterparts while simultaneously stabilizing the resulting structures [1]. This biogenic process occurs through both intracellular and extracellular mechanisms, with plant-mediated synthesis emerging as particularly advantageous due to its simplicity, scalability, and diversity of available biological resources [24]. The strategic deployment of green-synthesized nanoparticles spans multiple high-impact domains, including targeted drug delivery, wound healing, environmental remediation, antimicrobial applications, and agricultural protection [1] [24] [25].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Nanoparticle Synthesis Methods

| Parameter | Chemical Synthesis | Physical Synthesis | Green Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Impact | Toxic solvents, hazardous byproducts | High energy consumption | Eco-friendly, biodegradable materials |

| Cost Factors | Expensive chemicals, waste management | Specialized equipment, high energy costs | Affordable biological materials, minimal processing |

| Toxicity Profile | Often cytotoxic, requires further functionalization | Variable, depends on method | Generally biocompatible, lower toxicity |

| Energy Requirements | Moderate to high | Very high | Low (ambient temperature/pressure) |

| Scalability | Highly scalable | Limited by energy costs | Highly scalable with biomass resources |

| Sample Applications | Standard metallic NPs | Laser-ablated NPs | Plant-based Ag/Au NPs, microalgal NPs |

Sustainability Advantages

Environmental Compatibility and Resource Efficiency

Green synthesis methodologies fundamentally address sustainability challenges through environmentally responsible production processes that eliminate toxic reagents and minimize energy consumption. Unlike conventional approaches that employ hazardous reducing agents like sodium borohydride or cytotoxic stabilizing compounds, plant-based synthesis utilizes naturally occurring phytochemicals—including flavonoids, phenols, alkaloids, and terpenoids—as reducing and capping agents [1] [24]. This strategic substitution prevents the introduction of persistent pollutants into ecosystems and aligns with circular economy principles by transforming agricultural waste into valuable nanomaterials [26]. The sustainability profile is further enhanced through energy-efficient operations conducted at ambient temperature and pressure, significantly reducing the carbon footprint associated with nanoparticle manufacturing [1].

The integration of green nanoparticles into circular economy models represents a transformative approach to material life cycle management. Current innovations demonstrate the utilization of agricultural waste streams and renewable plant matter as source materials for nanoparticle synthesis, effectively converting low-value biomass into high-value nanomaterials [26]. This waste-to-resource paradigm simultaneously addresses disposal challenges while creating sustainable material sources. Furthermore, the biodegradable and non-toxic properties of green-synthesized nanoparticles make them ideal candidates for applications designed to minimize environmental impact, including eco-friendly packaging, low-impact textiles, and biodegradable medical implants [26]. The compatibility of these nanomaterials with biological systems enables their seamless integration into natural biogeochemical cycles at end-of-life, creating closed-loop systems that dramatically reduce resource strain and waste accumulation.

Sustainable Feedstocks and Scalability

Plant-mediated synthesis leverages global phytodiversity as renewable feedstock, with extensive documentation of successful nanoparticle synthesis using commonly available species such as Moringa oleifera, Psidium guajava, and numerous other agricultural resources [27]. This approach eliminates dependence on geologically scarce or conflict-prone elements that often constrain conventional nanomanufacturing. The extensive biodiversity available provides a virtually unlimited palette of biological reducing agents with distinct biochemical properties, enabling fine-tuning of nanoparticle characteristics without synthetic chemistry [24]. The cultivation of these biological resources simultaneously contributes to carbon sequestration and ecosystem preservation, particularly when utilizing perennial species or integrating nanoparticle production into agroforestry systems.

Scalability remains a critical advantage, with green synthesis demonstrating compatibility with industrial-scale production requirements while maintaining environmental compatibility. Microalgae-based systems exemplify this potential, offering high growth rates, minimal land requirements, and continuous cultivation independent of seasonal variations [5]. Unlike resource-intensive physical methods like laser ablation or chemical vapor deposition, biological synthesis can be implemented with basic laboratory equipment, making the technology accessible across economic contexts [27]. The decentralized production model demonstrated by initiatives such as women-run cooperatives in Sub-Saharan Africa producing plant-based nanoparticles for water purification highlights the potential for distributed manufacturing that reduces transportation emissions while building local economic resilience [26].

Cost-Effectiveness

Economic Advantages in Synthesis and Processing

The economic superiority of green synthesis stems from significant reductions in multiple cost centers: raw material acquisition, specialized equipment requirements, energy consumption, and waste management. Conventional chemical synthesis necessitates expensive metal precursors and toxic reducing agents, while physical methods require capital-intensive equipment for high-energy processes [16]. In contrast, green synthesis utilizes inexpensive biological materials, often sourced from agricultural waste or widely available biomass, dramatically reducing precursor costs [27]. The process operates effectively at ambient temperature and pressure, eliminating the need for energy-intensive heating, cooling, or pressure control systems that contribute substantially to operational expenses in traditional nanoparticle fabrication [1].

Equipment simplification presents another substantial economic advantage, as green synthesis typically requires only basic laboratory apparatus—beakers, stirrers, and standard filtration systems—rather than the specialized reactors, high-vacuum systems, or laser ablation equipment essential for conventional methods [25]. This significantly lowers barriers to implementation for research institutions and production facilities with limited capital resources. Additionally, the elimination of hazardous waste streams removes the substantial costs associated with chemical disposal, environmental monitoring, and regulatory compliance [16]. The cumulative effect of these efficiencies makes green synthesis particularly suitable for scaling to industrial production levels while maintaining favorable economics, especially when implemented in regions with abundant biomass resources [24].

Resource Efficiency and Process Optimization

Green synthesis demonstrates exceptional material efficiency through high atom economy and minimal purification requirements. The biological reducing agents facilitate rapid and complete reduction of metal precursors, with reaction times often ranging from minutes to a few hours [24]. This efficiency is exemplified in synthesis protocols using Bombyx mori cocoon extract, where simple processing yields silver nanoparticles with well-defined characteristics in less than 24 hours total processing time [25]. The capping agents naturally present in biological extracts stabilize the nanoparticles against aggregation, eliminating the need for additional synthetic stabilizers and simplifying downstream processing [1].

The integration of artificial intelligence further enhances cost-effectiveness by accelerating process optimization and reducing experimental overhead. AI-powered tools predict optimal plant extract combinations, metal precursor concentrations, and reaction parameters to maximize yield and control nanoparticle characteristics [26]. This computational guidance minimizes the traditional trial-and-error approach, significantly reducing material and time investments during process development. The economic viability is reinforced by the high reproducibility of green synthesis protocols, with numerous studies demonstrating consistent nanoparticle batches using standardized biological extracts [27]. This reliability ensures minimal production losses and consistent product quality, both critical factors for commercial applications in regulated industries like pharmaceuticals and biomedicine.

Table 2: Cost-Benefit Analysis of Green Synthesis Reagents

| Reagent Category | Traditional Synthesis | Green Synthesis | Economic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reducing Agents | Sodium borohydride, Hydrazine | Plant extracts (e.g., Moringa, Guava) | 60-80% cost reduction |

| Stabilizing Agents | Synthetic polymers (e.g., PVP) | Natural phytochemicals | 70-90% cost reduction |

| Solvent Systems | Organic solvents (e.g., toluene) | Water-based systems | 50-70% cost reduction, eliminates hazardous waste |

| Energy Input | High temperature/pressure | Ambient conditions | 80-90% energy reduction |

| Waste Management | Toxic byproduct treatment | Biodegradable byproducts | Eliminates specialized disposal costs |

Reduced Toxicity

Biocompatibility and Safety Profiles

Green-synthesized nanoparticles exhibit inherently superior biocompatibility and reduced toxicity compared to their chemically synthesized counterparts, a critical advantage for biomedical applications. This enhanced safety profile originates from the biological capping agents that naturally coat the nanoparticles during synthesis, comprising phytochemicals, proteins, and polysaccharides that are intrinsically compatible with biological systems [1]. These biomolecules create a protective corona that minimizes direct contact between the metal core and biological tissues, reducing oxidative stress and cellular damage [25]. Toxicity assessments across multiple studies consistently demonstrate significantly lower adverse effects for green-synthesized nanoparticles, as exemplified by silk-derived silver nanoparticles showing minimal impact on normal HFB-4 cells (IC₅₀ = 582.33 ± 6.37 µg/mL) while maintaining potent activity against cancer cell lines [25].

The therapeutic index—a quantitative measure of safety efficacy—is substantially widened for green-synthesized nanoparticles, creating enhanced windows for therapeutic intervention. This differential toxicity enables targeted applications where malignant cells are selectively eliminated while healthy tissues remain protected [5]. The mechanism underlying this selectivity involves receptor-mediated interactions and preferential uptake in target cells, contrasted with the non-specific adsorption common to chemically synthesized nanoparticles that lack biological recognition elements [1]. The natural composition of the capping layers also reduces immunogenic responses, making green-synthesized nanoparticles better tolerated for in vivo applications including drug delivery, wound healing, and diagnostic imaging [25].

Environmental Toxicology and Degradation

Beyond biomedical applications, green-synthesized nanoparticles demonstrate markedly reduced ecotoxicity, addressing one of the primary concerns regarding nanotechnology environmental impact. The biological encapsulation facilitates natural degradation pathways through microbial action and environmental processes, preventing persistent accumulation in ecosystems [24]. This contrasts sharply with synthetic stabilizers used in conventional nanoparticles, which can resist degradation and potentially introduce new environmental contaminants. Studies of plant-based nanoparticles in agricultural applications confirm effective nematode control without the soil toxicity associated with chemical nematicides, highlighting their environmental compatibility [24].

The reduced ecological impact extends throughout the nanoparticle lifecycle, from synthesis to disposal. Green synthesis eliminates the hazardous byproducts generated during chemical synthesis, preventing ecosystem contamination at the production phase [16]. The nanoparticles themselves, when released into environmental compartments, undergo more rapid and complete biodegradation into benign constituents [26]. This comprehensive safety profile positions green-synthesized nanoparticles as sustainable alternatives for large-scale environmental applications including water purification, soil remediation, and agricultural management where conventional nanoparticles would pose unacceptable ecological risks [26] [24].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Plant-Mediated Synthesis Protocol

The plant-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles follows a rigorously standardized protocol that ensures reproducibility and consistent quality. The process begins with the preparation of plant extract, typically using 10-50g of thoroughly washed plant material (leaves, roots, or stems) boiled in 100-500mL of deionized water for 10-30 minutes [24] [27]. The resulting extract is filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper to remove particulate matter, yielding a clear solution containing the bioactive compounds responsible for metal ion reduction. For the synthesis reaction, a 1-10mM solution of metal salt (e.g., AgNO₃ for silver nanoparticles, HAuCl₄ for gold nanoparticles, FeSO₄·7H₂O for iron nanoparticles) is prepared in deionized water [27]. The critical synthesis step involves combining the plant extract with metal salt solution in ratios typically ranging from 1:9 to 3:7 (v/v) under continuous stirring at ambient temperature [24].

The reaction progress is monitored visually through color change—from pale yellow to brown for silver nanoparticles, to ruby red for gold nanoparticles, and to deep black for iron oxide nanoparticles [25] [27]. Completion typically occurs within minutes to hours, after which the nanoparticles are recovered by centrifugation at 10,000-15,000 rpm for 15-30 minutes. The pellet is washed multiple times with deionized water or ethanol to remove unreacted components and then dried at 60-80°C to obtain the final nanoparticle powder [27]. For enhanced crystallinity, a calcination step may be incorporated, typically at 300-600°C for 2-4 hours in a muffle furnace [27]. This protocol yields well-characterized nanoparticles with controlled sizes between 5-50nm, as confirmed by TEM analysis, with variations dependent on the specific plant extract and metal salt combination [25].

Microalgae-Based Synthesis Protocol

Microalgae-mediated synthesis represents a particularly sustainable approach, leveraging the metabolic activities of photosynthetic microorganisms. The protocol begins with the cultivation of microalgae species such as Chlorella vulgaris or Spirulina platensis in suitable growth media (e.g., BG-11 for freshwater species) under controlled light (100-200 µmol photons/m²/s) and temperature (25-30°C) conditions with continuous aeration [5]. Biomass is harvested during the late exponential growth phase (typically 7-14 days) by centrifugation at 5000-8000 rpm for 10 minutes, followed by washing to remove media components [5]. The cleaned biomass is then used for nanoparticle synthesis through either intracellular or extracellular methods.

For extracellular synthesis, the algal biomass is subjected to extraction using deionized water, ethanol, or methanol at 60-80°C for 1-2 hours to release bioactive compounds [5]. The filtered extract is then combined with metal salt solution as described in the plant-mediated protocol. Intracellular synthesis involves suspending live algal biomass in metal salt solution, where the nanoparticles form within the cells over 24-72 hours [5]. The intracellular nanoparticles are subsequently released through cell disruption methods such as sonication or French press treatment, followed by purification through differential centrifugation. The microalgae-mediated approach is particularly valuable for producing nanoparticles with enhanced biocompatibility for drug delivery applications, as the natural algal metabolites create superior surface functionalization for biological interactions [5].

Characterization and Analytical Methods

Essential Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive characterization of green-synthesized nanoparticles requires a multidisciplinary analytical approach to confirm size, morphology, composition, and surface properties. UV-visible spectroscopy serves as the primary rapid assessment tool, with surface plasmon resonance peaks indicating nanoparticle formation—typically around 420 nm for silver nanoparticles, 520-550 nm for gold nanoparticles, and 300-400 nm for iron oxide nanoparticles [25]. Spectral monitoring throughout the reaction provides insights into nucleation and growth kinetics, with peak sharpness serving as a proxy for size distribution and colloidal stability [27].

Advanced microscopy techniques deliver critical morphological data, with Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) providing direct visualization of nanoparticle size, shape, and dispersion at nanometer resolution [25]. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) complements TEM by offering three-dimensional topological information and larger area assessment [27]. Crystalline structure and phase composition are determined through X-Ray Diffraction (XRD), with characteristic peaks confirming specific crystal structures—for instance, the distinctive patterns of magnetite (Fe₃O₄) versus hematite (Fe₂O₃) nanoparticles [27]. Surface functionalization by biological capping agents is verified through Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), identifying characteristic functional groups (hydroxyl, carbonyl, amine) from phytochemical constituents [25].

Performance and Stability Assessment

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) provides hydrodynamic size distribution and polydispersity indices in solution, while Zeta potential measurements quantify surface charge and predict colloidal stability, with values exceeding ±30 mV indicating stable suspensions [24]. The biological functionality of green-synthesized nanoparticles is validated through specialized assays tailored to application requirements. Antibacterial efficacy employs standard disc diffusion or broth microdilution methods against Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens [25]. Antioxidant capacity is quantified through DPPH radical scavenging assays, with IC₅₀ values comparing favorably to standard antioxidants like ascorbic acid [25]. Cytotoxic activity against cancer cell lines is evaluated through MTT or similar viability assays, establishing dose-response relationships and selective toxicity indices [25].

Table 3: Biological Activity Metrics of Green-Synthesized Nanoparticles

| Nanoparticle Type | Source Material | Antibacterial Activity (Zone of Inhibition) | Antioxidant (DPPH IC₅₀) | Cytotoxicity (Cancer Cell IC₅₀) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silver NPs | Bombyx mori cocoon | 11-20mm against S. aureus, E. coli | 4.94 µg/mL | 177.24 µg/mL (Caco-2) |

| Silver NPs | Cucumis prophetarum leaf | 11-20mm against S. aureus, S. typhi | Not reported | Not reported |

| Iron Oxide NPs | Moringa oleifera | Moderate bioactivity | Not reported | Not reported |

| Iron Oxide NPs | Psidium guajava | Moderate bioactivity | Not reported | Not reported |

| Gold NPs | Plant extracts (various) | Variable based on source | Typically <10 µg/mL | Variable by cancer cell type |

Long-term stability represents a critical performance metric, with green-synthesized nanoparticles typically maintaining structural integrity and functional properties for extended periods when stored under appropriate conditions [1]. The natural capping agents provide superior protection against aggregation and oxidation compared to synthetic stabilizers, particularly for reactive metal nanoparticles. Accelerated stability studies under varying temperature, pH, and ionic strength conditions provide predictive data for real-world application performance [27]. This comprehensive characterization paradigm ensures rigorous quality control and establishes structure-activity relationships that guide the rational design of green-synthesized nanoparticles for specific applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Green Nanoparticle Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Synthesis | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Materials | Fresh or dried leaves, roots, fruits | Source of reducing and stabilizing agents | Moringa oleifera, Psidium guajava [27] |

| Metal Salts | High purity (>98%) water-soluble salts | Precursor for nanoparticle formation | AgNO₃, HAuCl₄, FeSO₄·7H₂O [25] [27] |

| Extraction Solvent | Deionized/Distilled water | Medium for extracting bioactive compounds | DI water (resistivity >18 MΩ·cm) [24] |

| Filtration System | Standard laboratory filter paper | Removal of particulate matter from extracts | Whatman No. 1 or equivalent [27] |

| Centrifugation | Laboratory centrifuge | Nanoparticle recovery and purification | 10-15k rpm capability [25] |

| pH Measurement | Digital pH meter | Monitoring reaction conditions | Standard laboratory pH meter [27] |

| Characterization | Spectrophotometer, TEM, XRD, FTIR | Nanoparticle validation and analysis | UV-Vis, TEM, XRD instrumentation [25] [27] |

The compelling advantages of green nanoparticle synthesis—superior sustainability, demonstrable cost-effectiveness, and significantly reduced toxicity—establish this methodology as the foundation for next-generation nanomaterial production. The technical protocols and empirical data presented in this whitepaper provide researchers and industry professionals with validated approaches for implementing these environmentally responsible synthesis routes. As the field advances, the integration of AI-assisted optimization [26], genetically engineered biological systems [5], and standardized quality control regimes will further enhance the capabilities and applications of green-synthesized nanoparticles. The ongoing translation of these sustainable nanomaterials into commercial products represents a critical pathway toward reconciling technological advancement with ecological stewardship, particularly in sensitive applications including drug development, environmental remediation, and agricultural enhancement.

The synthesis of nanoparticles via green routes has emerged as a reliable, sustainable, and eco-friendly protocol in materials science, representing a crucial tool for reducing the destructive effects associated with traditional synthesis methods [28]. Green synthesis methods utilize biological entities such as plants, algae, bacteria, yeast, and fungi to produce a wide range of nanomaterials, including metal nanoparticles, metal oxides, and semiconductors [29] [30]. This approach is fundamentally aligned with green chemistry principles, emphasizing prevention of waste, resource efficiency, and the use of safer solvents and renewable feedstocks [16] [28]. Unlike conventional chemical and physical methods that often involve toxic chemicals, high energy input, and generate harmful byproducts, green synthesis operates through biological reduction processes that are environmentally responsible, economical, and biologically safe [16] [1] [30].

The growing emphasis on sustainable nanotechnology has positioned green synthesis as an essential methodology for producing nanoparticles with exceptional mechanical, chemical, biological, thermal, and physical qualities [16]. These biogenic nanoparticles demonstrate enhanced biocompatibility and biological activity compared to those produced through chemical routes, making them particularly valuable for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications [29] [1]. The fundamental advantage of green synthesis lies in its utilization of natural biological systems to utilize their intrinsic organic chemistry processes in remodeling inorganic metal ions into nanoparticles, thus opening undiscovered areas of biochemical analysis [30].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Green Synthesis

Biological Reduction Pathways

Green synthesis of nanoparticles occurs through specialized biological reduction mechanisms where biomolecules from various biological entities act as both reducing and stabilizing agents [29] [1]. The process fundamentally involves the bio-reduction of metal precursor salts into their nanoscale forms, followed by stabilization through capping agents present in the biological systems [30]. These reduction capabilities are often part of the organism's resistance mechanisms against metal toxicity [30]. The synthesis can occur either intracellularly (within cells) or extracellularly (outside cells), with extracellular synthesis generally preferred for easier purification and higher production rates [30].

The specific reduction mechanisms vary significantly across different biological systems. Plants typically employ phytochemicals such as polyphenols, flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids, amides, and aldehydes to reduce metal ions [29] [28]. These compounds possess oxidation-reduction capabilities that facilitate the conversion of metal ions into stable nanoparticles [1]. Bacteria utilize enzymes like nitrate reductase to reduce metal ions both inside and outside cells [29]. Certain bacterial species, such as Delftia acidovorans, produce specific peptides like delftibactin that induce resistance against toxic metal ions through nanoparticle formation [30]. Fungi employ enzymes including laccase and reductase for metal ion reduction and nanoparticle stabilization [29], while yeast utilizes mechanisms such as nitrate reductase for extracellular synthesis and metallothioneins for intracellular synthesis [29]. Algae harness compounds like chlorophylls and carotenoids in their reduction processes [29].

Key Synthesis Parameters and Control