From Biomarker to Beacon: Designing and Deploying Nanonetwork Alarm Systems for Early Disease Detection

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of alarm-system nanonetworks engineered for biomarker detection.

From Biomarker to Beacon: Designing and Deploying Nanonetwork Alarm Systems for Early Disease Detection

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of alarm-system nanonetworks engineered for biomarker detection. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we detail the foundational concepts of these bio-inspired communication systems, including their core components like biosensors, nano-transceivers, and receivers. We delve into methodological blueprints for network design, signal processing, and *in vitro*/*in vivo* applications. Critical challenges such as signal interference, biocompatibility, and power constraints are addressed with practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, we present a rigorous framework for validating network performance, comparing technological platforms (e.g., DNA-based vs. synthetic nanoparticle networks), and assessing their clinical translatability. This guide synthesizes current research to advance the development of precise, proactive diagnostic tools.

Decoding the Blueprint: Core Components and Principles of Biomarker Alarm Nanonetworks

A Biomarker Alarm-System Nanonetwork is an integrated, engineered system comprising nanoscale components (synthetic or bio-hybrid) designed for continuous, in vivo monitoring of disease-specific molecular biomarkers. Upon detection of a pathological concentration threshold, the network autonomously triggers a multi-stage, amplified signal—an "alarm"—communicatable to external devices or capable of initiating a therapeutic response. This whitepaper details its core architecture and operational principles within the broader thesis of foundational research for such systems.

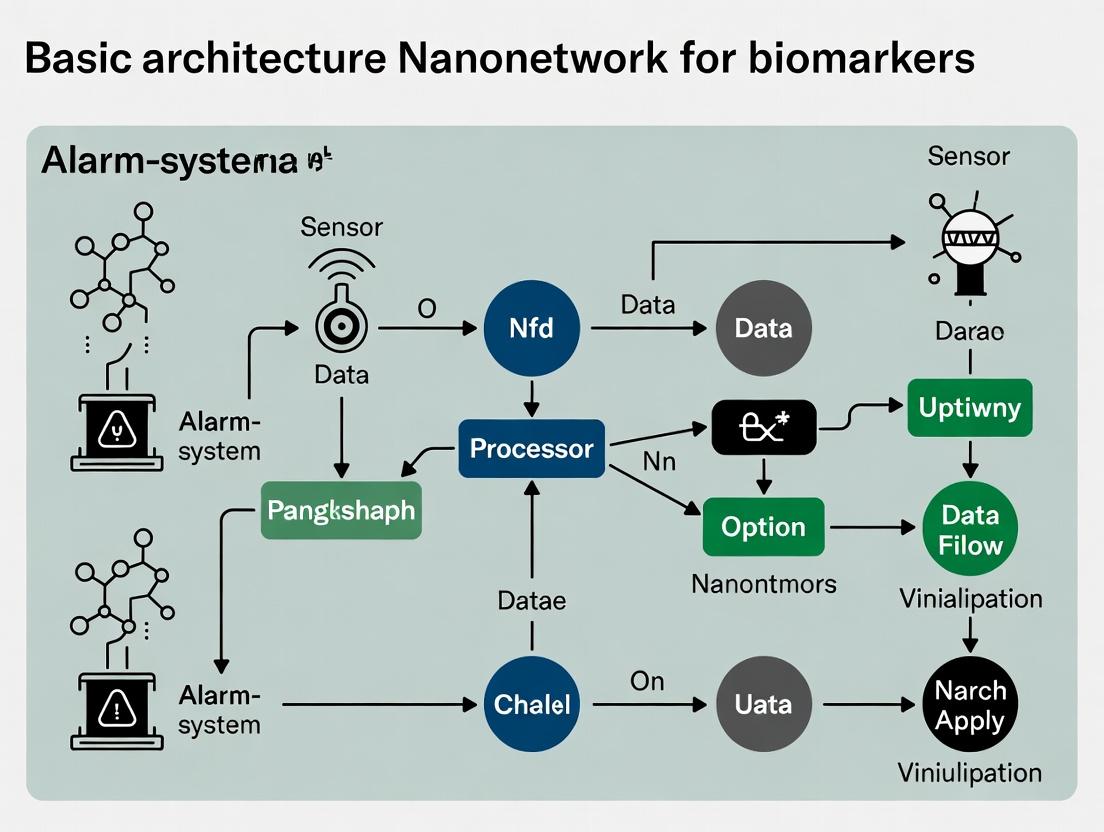

Core Architectural Framework

The basic architecture is a hierarchical network with distinct functional layers, enabling sensing, computation, communication, and actuation.

Table 1: Core Functional Layers of the Alarm-System Nanonetwork

| Layer | Primary Function | Key Nanoscale Components | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensing | Target biomarker recognition and binding. | Functionalized nanoparticles, engineered nanopores, DNA/RNA aptamers, molecular imprinting polymers. | Biomarker-binding event transduced into a chemical or conformational change. |

| Signal Transduction & Amplification | Convert binding event into a scalable, propagatable signal. | Enzyme cascades (e.g., horseradish peroxidase), nanoparticle quenching/de-quenching, DNAzyme networks, biocatalytic circuits. | Amplified chemical output (e.g., fluorescence, chemiluminescence, ionic flux). |

| Communication & Networking | Relay signal between nodes and to an external interface. | Diffusive molecular communication (calcium waves, ROS species), Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) chains, wireless electromagnetic (nanoscale antenna). | Coordinated network response surpassing single-node detection limits. |

| Actuation & Reporting | Generate a readable alarm or primary therapeutic effect. | Release of reporter molecules (dyes, peptides), generation of gas bubbles (for ultrasound), triggered drug release from nanocarriers. | Externally detectable signal (e.g., colorimetric urine change, MRI contrast) or localized pharmacological action. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Validation of a Protease-Activated FRET Nanosensor Network

- Objective: To demonstrate network-based signal amplification for a disease-specific protease biomarker (e.g., MMP-9).

- Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

- Methodology:

- Nanosensor Synthesis: Conjugate donor (Cy3) and acceptor (Cy5) fluorophores to a peptide substrate linker specific for MMP-9 cleavage. Attach this construct to a 20nm PEGylated quantum dot (QD) core.

- Network Formation: Mix QD-sensors with cationic liposomes to facilitate aggregation into a nanonetwork cluster via electrostatic interaction. Characterize cluster size using dynamic light scattering (DLS).

- Signal Acquisition: Incubate the nanonetwork with recombinant MMP-9 (10 nM-1 µM range) in a physiological buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C.

- Data Measurement: Use a fluorescence plate reader to monitor time-dependent loss of FRET (increase in donor emission at 570nm, decrease in acceptor emission at 670nm upon excitation at 530nm). Compare signal kinetics and amplitude against dispersed, non-networked sensors.

Protocol 2: Evaluation of a Glucose-Responsive DNAzyme Cascade for Alarm Triggering

- Objective: To implement a nucleic acid-based amplification circuit that triggers a colorimetric alarm upon sensing hyperglycemia.

- Materials: DNAzyme sequences (8-17E), glucose oxidase (GOx), hemin, horseradish peroxidase (HRP), ABTS substrate, synthetic urine matrix.

- Methodology:

- Circuit Assembly: Mix the substrate strand for the DNAzyme with the enzyme strand in a buffer containing hemin to form the active G-quadruplex DNAzyme structure.

- Integration with Biomarker Sensor: Incorporate GOx into the system. GOx converts glucose to gluconic acid and H₂O₂.

- Cascade Activation: The generated H₂O₂ acts as the co-substrate for the HRP-mimicking DNAzyme.

- Alarm Readout: Add ABTS (2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)). Oxidation by the DNAzyme-H₂O₂ system produces a green-colored product, measurable at 405-420 nm. Calibrate against glucose concentrations (5-30 mM).

Visualizing Signaling Pathways & Workflows

(Diagram Title: Core Alarm Nanonetwork Signal Pathway)

(Diagram Title: Biomarker Alarm System Development Workflow)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Prototype Development

| Item | Function in Research | Example & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Nanoparticles | Core sensing platform. | Gold Nanorods (AuNRs): High surface-area-to-volume ratio for biomarker capture; tunable plasmonic properties for photothermal signal transduction. |

| DNA Aptamers / DNAzymes | High-specificity recognition and catalytic elements. | SELEX-derived Aptamer for PSA: Provides synthetic, stable alternative to antibodies for prostate-specific antigen detection in sensor design. |

| Fluorescent Reporters (FRET Pairs) | For optical signal generation and intra-network communication. | Cy3-Cy5 FRET Pair: Attached via cleavable peptide linker; cleavage by target protease disrupts FRET, generating an optical alarm signal. |

| Enzyme Cascades | Provides intrinsic biochemical signal amplification. | Glucose Oxidase (GOx) + Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP): GOx produces H₂O₂ from glucose; HRP uses H₂O₂ to oxidize a substrate, creating a colorimetric/chemiluminescent readout. |

| Synthetic Biological Matrices | For testing in physiologically relevant conditions. | Artificial Interstitial Fluid / Urine: Validates sensor performance against complex backgrounds with ions, proteins, and pH variations, prior to in vivo studies. |

| Animal Disease Models | For ultimate in vivo validation of alarm function. | Transgenic Mouse Model of Colitis (e.g., IL-10 knockout): Provides a living system to test nanonetworks for biomarkers like TNF-α or calprotectin in real-time. |

This whitepaper details the foundational architecture for an alarm-system nanonetwork designed for biomarker research. The system's core objective is the real-time, in situ detection of specific molecular biomarkers, triggering a coordinated, amplifiable signal to an external receiver. This architecture is critical for advancing drug development, enabling researchers to monitor therapeutic efficacy and disease progression at the molecular level within model organisms or in vitro systems.

Architectural Breakdown of the Core Triad

Biosensors: The Molecular Recognition Element

Biosensors are the network's frontline, comprising engineered biological or synthetic components that bind a target biomarker with high specificity.

Key Design Principles:

- Target: Proteins (e.g., enzymes, cytokines), nucleic acids (miRNA, mRNA), or small molecules.

- Transduction Mechanism: Binding induces a conformational change, cleavage event, or release of a reporter molecule.

- Common Formats: Aptamers, engineered proteins (antibody fragments, DARPins), or allosteric ribozymes.

Nano-Nodes: The Signal Processor and Transmitter

Nano-nodes are nanoscale devices (often synthetic or hybrid particles) that interface with biosensors. They convert the molecular binding event into a transmissible signal.

Primary Functions:

- Signal Amplification: Catalytically generate many secondary messenger molecules per binding event.

- Signal Encoding: Modulate the signal's identity (e.g., type of molecule, pulse frequency) based on biomarker concentration or identity.

- Local Communication: Diffuse or actively relay signals to nearby nano-nodes or the Hub.

Hub/Receiver: The Signal Aggregator and External Interface

The Hub is a centralized nano-device or modified cell that collects signals from multiple nano-nodes. The Receiver is the macroscale instrument that detects the Hub's output.

Hub Operations:

- Signal Integration: Summarizes inputs from a network region.

- Noise Filtering: Applies thresholds to reduce false positives.

- Macro-Signal Generation: Produces an externally detectable signal (e.g., magnetic, acoustic, radiofrequency, or strong fluorescent pulse).

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Current Nanonetwork Components (Representative Data)

| Component | Metric | Typical Range (Current Systems) | Target for Alarm Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biosensor | Dissociation Constant (Kd) | pM - nM | < 1 nM |

| Response Time | Seconds - Minutes | < 60 Seconds | |

| Specificity (Cross-Reactivity) | 5-15% | < 1% | |

| Nano-Node | Signal Amplification Factor | 10^2 - 10^4 per event | > 10^5 per event |

| Communication Range | 1 - 20 μm | 50 - 100 μm | |

| Power Source (if synthetic) | Biochemical / External (e.g., magnetic, ultrasonic) | Endogenous biochemical | |

| Hub/Receiver | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | 10 - 30 dB | > 40 dB |

| Detection Limit (Biomarker Conc.) | nM - pM in vitro | fM in complex media | |

| Latency (Event to Readout) | Minutes - Hours | < 10 Minutes |

Table 2: Comparison of Primary Signaling Modalities for Nanonetworks

| Modality | Example Messenger | Advantages | Disadvantages for In Vivo Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Diffusion | Calcium ions, IP3, DNA strands | Biocompatible, no external power needed. | Slow, subject to enzymatic degradation. |

| Acoustic | Pressure waves | Good tissue penetration, tunable frequency. | Low spatial resolution, requires external transducer. |

| Magnetic | Superparamagnetic nanoparticle (SPION) rotation | Deep tissue penetration, low background noise. | Requires strong external magnetic field generators. |

| Optical | FRET, Bioluminescence | High spatiotemporal resolution, multiplexing. | Limited tissue penetration, autofluorescence. |

| Radiofrequency/EM | Engineered nanoparticle resonance | Potential for deep penetration. | Technical challenges in miniaturization and control. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 4.1:In VitroValidation of a Protease-Activated Biosensor-Nano-Node Assembly

Objective: To test the activation and amplification kinetics of a nano-node triggered by MMP-9 protease cleavage.

Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" (Section 6). Procedure:

- Functionalization: Immobilize the quenched fluorescent peptide substrate (biosensor) onto the surface of the liposomal nano-node (pre-loaded with Texas Red dextran) via a streptavidin-biotin linkage.

- Baseline Measurement: Aliquot the functionalized nano-nodes into a 96-well plate. Acquire baseline fluorescence (Ex/Em: 488/520 nm for FRET quench; 595/615 nm for Texas Red) using a plate reader.

- Stimulation: Add recombinant human MMP-9 to experimental wells at final concentrations ranging from 0.1 nM to 100 nM. Use buffer-only controls.

- Kinetic Readout: Immediately initiate kinetic fluorescence measurements every 30 seconds for 2 hours at 37°C.

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence intensity over time. Calculate the rate of signal increase (slope) for each MMP-9 concentration. Determine the limit of detection (LOD) and the effective amplification factor (ratio of Texas Red signal increase to cleaved peptide molecules).

Protocol 4.2: Testing Hub-Based Signal Integration in a Microfluidic Chamber

Objective: To demonstrate that a hub particle can sum inputs from multiple, spatially separated nano-nodes.

Materials: Streptavidin-coated magnetic hub particles, two populations of nano-nodes (emitting distinct DNA "Z" and "Y" strands upon activation), microfluidic mixing device, qPCR system. Procedure:

- Compartmentalized Activation: Load the microfluidic device. In one channel, introduce nano-node population "Z" with its target biomarker. In a separate, parallel channel, introduce nano-node population "Y" with a different target. Allow activation to proceed for 15 minutes.

- Hub Introduction & Capture: Mix the effluents from both channels in a central chamber containing the hub particles. The hub surface is functionalized with complementary DNA strands to capture "Z" and "Y" output strands.

- Incubation & Washing: Incubate for 30 minutes to allow hybridization. Apply a magnetic field to sequester hub particles and wash away unbound strands.

- Hub Interrogation: Elute the bound DNA strands from the hub particles. Quantify the concentrations of "Z" and "Y" strands via qPCR using unique primer sets.

- Analysis: Correlate the ratio and quantity of "Z" and "Y" strands on the hub to the original biomarker concentrations in the separate channels, demonstrating integrative capture.

Visualizations (Graphviz Diagrams)

Diagram 1: Core Triad Signaling Pathway Flow

Diagram 2: General Experimental Workflow for Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function in Nanonetwork Research | Example Product / Material |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Liposomes / Polymersomes | Serve as versatile nano-node cores for encapsulating reporters and surface-presenting biosensors. | DSPC/Cholesterol liposomes, PEG-PLGA polymersomes. |

| Streptavidin-Biotin Conjugation System | Provides a robust, high-affinity link for attaching biosensors (e.g., biotinylated aptamers) to nano-node surfaces. | Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads, EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-Biotin. |

| FRET-Based Peptide Substrates | Act as cleavable biosensors for protease biomarkers; cleavage disrupts FRET, generating a signal. | Custom peptides with donor/acceptor pairs (e.g., FAM/QXL). |

| DNA Oligonucleotide "Toehold" Switches | Used as programmable, amplifiable biosensors and for inter-node communication via strand displacement. | Custom ssDNA from IDT or Sigma. |

| Recombinant Target Biomarkers | Essential positive controls for calibrating and validating biosensor response in vitro. | Recombinant proteins (e.g., R&D Systems, Abcam). |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) / Upconversion NPs | Act as stable, bright optical reporters within nano-nodes or hubs for deep-tissue signal potential. | CdSe/ZnS QDs, NaYF4:Yb,Er UCNPs. |

| Microfluidic Mixing/Encapsulation Device | Enables precise assembly of nano-network components and testing under controlled flow conditions. | Dolomite Microfluidic Chips. |

| Plate Reader with Kinetic Capability | For high-throughput, time-resolved measurement of optical signals (fluorescence, luminescence). | BioTek Synergy H1, BMG CLARIOstar. |

This whitepaper details the fundamental mechanisms by which the binding of a target biomarker initiates a sequence of nanoscale events, culminating in a detectable signal within an alarm-system nanonetwork. This process is the cornerstone of next-generation diagnostic and drug development platforms.

Within the proposed architecture for an alarm-system nanonetwork, individual nodes are engineered nanostructures designed for specific biomarker surveillance. The "alarm" is a cascade of signal translation events, transforming molecular recognition into a transmissible output. This document deconstructs the core cascade following biomarker binding.

The Core Signaling Cascade: A Stepwise Deconstruction

The cascade follows a generalizable pathway from recognition to signal generation.

Stage 1: Biomarker Recognition and Conformational Change

The initial binding event occurs at a biorecognition element (e.g., an antibody, aptamer, or molecularly imprinted polymer). Binding energy induces a precise conformational rearrangement in the receptor or the surrounding nanostructure.

Stage 2: Proximal Transducer Activation

The conformational change alters the local chemical or physical environment, activating a proximal transducer. This can involve:

- Enzymatic Activation: An enzyme co-localized with the receptor becomes active or accesses its substrate.

- Energy Transfer Modulation: The distance or orientation between a donor and acceptor (e.g., FRET pair) changes, altering energy transfer efficiency.

- Electron Transfer Gate: Binding opens or closes a pathway for electron flow in an electrochemical sensor.

- Steric Shield Removal: Binding displaces a quenching molecule or unveils a reactive site.

Stage 3: Signal Amplification

To detect low-abundance biomarkers, the activated transducer triggers an amplification loop.

- Catalytic Amplification: A single activated enzyme generates thousands of product molecules (e.g., horseradish peroxidase with chromogenic substrate).

- Nanoparticle Growth: The initial product catalyzes the deposition of metal onto a nanoparticle seed, dramatically increasing its size and optical cross-section.

- Cascade Reaction: The product of the first reaction is a catalyst or cofactor for a second, orthogonal reaction.

Stage 4: Output Signal Generation

The amplified intermediate is converted into a final, transmissible signal within the nanonetwork.

- Optical: Emission of light at a specific wavelength (fluorescence, chemiluminescence) or a shift in plasmonic resonance (color change).

- Magnetic: Aggregation of superparamagnetic nanoparticles alters T2 relaxation time for MRI detection.

- Electrochemical: Generation or consumption of redox-active molecules produces a measurable current.

- Acoustic: Changes in nanoparticle mass or stiffness upon binding affect ultrasound backscatter.

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters of Common Signal Translation Modalities

| Modality | Typical Biomarker Kd (M) | Amplification Factor | Limit of Detection (Molar) | Time to Signal (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Colorimetric | 10⁻⁹ – 10⁻¹² | 10³ – 10⁶ | 10⁻¹² – 10⁻¹⁵ | 5 – 30 |

| Fluorescence (Direct) | 10⁻⁹ – 10⁻¹² | 1 – 10 | 10⁻¹⁰ – 10⁻¹² | < 1 |

| Fluorescence (FRET) | 10⁻⁹ – 10⁻¹² | 1 – 10 | 10⁻¹¹ – 10⁻¹³ | 1 – 5 |

| Electrochemical (Amperometric) | 10⁻⁹ – 10⁻¹² | 10² – 10⁵ | 10⁻¹² – 10⁻¹⁵ | 2 – 15 |

| Plasmonic Shift (LSPR) | 10⁻⁹ – 10⁻¹² | 1 – 10² | 10⁻¹² – 10⁻¹⁵ | 1 – 10 |

Experimental Protocol: Validating an Aptamer-Based FRET Cascade

This protocol outlines a method to validate a conformational-change-driven cascade using a dye-quencher labeled aptamer.

Objective: To demonstrate that target biomarker binding induces a conformational shift, separating a fluorophore from a quencher, resulting in a measurable fluorescence increase.

Materials: See The Scientist's Toolkit below.

Procedure:

- Aptamer Conjugation: Reconstitute the thiol-modified DNA aptamer in PBS buffer (pH 7.4). Reduce disulfide bonds using 10 mM TCEP for 1 hour. Purify via desalting column.

- Dye/Quencher Labeling: React the reduced aptamer with a 10:1 molar excess of maleimide-functionalized fluorophore (Cy3) for 2 hours in the dark. Purify via HPLC to isolate single-labeled strands. Hybridize the complementary quencher strand (with Iowa Black RQ) at a 1.2:1 ratio in annealing buffer by heating to 95°C for 5 min and slowly cooling to 25°C over 45 min.

- Sensor Characterization: Dilute the dual-labeled aptamer construct to 100 nM in assay buffer. Acquire a fluorescence emission scan (excitation 550 nm, emission 560-750 nm) to establish the baseline quenched signal.

- Target Binding Assay: Aliquot 100 µL of the sensor solution into a 96-well plate. Add 10 µL of serial dilutions of the target biomarker (e.g., from 0.1 pM to 100 nM). Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes.

- Signal Measurement: Read the fluorescence intensity (ex/em 550/570 nm) for each well. Calculate the fold increase over the negative control (no target).

- Specificity Control: Repeat Step 4 with a high concentration (100 nM) of non-target biomarkers with similar structures.

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence intensity vs. log[target concentration]. Fit data to a 4-parameter logistic model to determine the EC₅₀ and dynamic range.

Visualization of Signaling Pathways

Title: Core Biomarker Signaling Cascade Pathway

Title: Aptamer Conformational Change FRET Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Role in Cascade | Example Product/Chemical |

|---|---|---|

| High-Affinity Capture Probes | Biorecognition element; dictates specificity and initial binding energy. | Monoclonal antibodies, DNA/RNA aptamers, peptide ligands, molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs). |

| Fluorescent Dyes & Quenchers | FRET pairs for transducing conformational changes into optical signals. | Cyanine dyes (Cy3, Cy5), Black Hole Quenchers, Iowa Black FQ/RQ. |

| Enzyme Labels | Catalytic amplifiers (e.g., for colorimetric or chemiluminescent output). | Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP), Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP), Glucose Oxidase. |

| Functionalized Nanoparticles | Signal enhancers and multivalent scaffolds. | Gold nanoparticles (for LSPR), quantum dots (bright fluorescence), magnetic beads (for separation). |

| Signal-Generating Substrates | Convert enzymatic or catalytic activity into measurable output. | TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) for HRP, CDP-Star for ALP, Ru(bpy)₃²⁺ for ECL. |

| Controlled Surface Chemistry Kits | For stable and oriented immobilization of probes on sensor surfaces. | NHS/EDC coupling kits, streptavidin-biotin systems, thiol-gold conjugation kits. |

| Microfluidic Flow Cells | Reproduce the dynamic environment for testing nanonetwork communication. | PDMS chips with integrated microchannels, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) chips. |

The basic architecture of an alarm-system nanonetwork for biomarker detection and response requires three core functions: sensitive signal detection, robust signal amplification/integration, and a decisive communicative output. Biological systems, honed by evolution, provide masterful blueprints for these functions. Quorum sensing (QS) in bacteria exemplifies population-scale decision-making based on biomarker (autoinducer) concentration. Eukaryotic cellular signaling pathways, such as kinase cascades, demonstrate exquisite sensitivity and signal amplification through multi-tiered transduction. This whitepaper details the mechanisms of these biological systems to inform the engineering of synthetic nanonetworks capable of monitoring biomarkers and triggering therapeutic or diagnostic "alarms" at defined thresholds.

Technical Analysis of Core Bio-Inspired Mechanisms

Quorum Sensing: A Model for Collective Decision-Making

Bacterial QS is a cell-density-dependent gene regulatory mechanism. Individual cells constitutively secrete small signaling molecules called autoinducers (AIs). As the population grows, the extracellular AI concentration increases proportionally. Upon reaching a critical threshold, AIs bind to specific receptor proteins, triggering a signal transduction cascade that alters gene expression for the entire population, enabling coordinated behaviors like bioluminescence, biofilm formation, and virulence factor secretion.

Key QS Systems for Nanonetwork Design:

- LuxI/LuxR-Type (Gram-negative): Uses acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) as AIs.

- Agr-Type (Gram-positive): Uses autoinducing peptides (AIPs) as AIs.

- AI-2 System (Interspecies): Uses furanosyl borate diester, a universal signal.

Quantitative Parameters of Model QS Systems:

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters of Characterized Quorum Sensing Systems

| System | Organism | Autoinducer (AI) | Receptor | Critical Threshold Concentration (Typical Range) | Key Regulated Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LuxI/LuxR | Aliivibrio fischeri | 3OC6-HSL (AHL) | LuxR | ~10 nM | Bioluminescence (luxCDABE operon) |

| LasI/LasR | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 3OC12-HSL | LasR | ~100 nM - 1 µM | Virulence factors, biofilm |

| Agr | Staphylococcus aureus | AIP-I | AgrC (membrane histidine kinase) | ~10 nM - 100 nM | Toxin production, dispersal |

| AI-2 | Vibrio harveyi | (S)-TMF-DPD | LuxPQ (complex) | Variable, for interspecies communication | Bioluminescence, metabolism |

Eukaryotic Signaling Pathways: Models for Signal Amplification & Integration

Cellular signaling pathways convert a small stimulus into a large, coordinated response. Key features ideal for alarm systems include:

- Amplification: A single activated receptor can trigger the activation of many downstream effectors (e.g., kinase cascades).

- Integration: Multiple signals converge on common nodes (e.g., MAPK pathways).

- Thresholding & Bistability: Ultrasensitive response curves and positive feedback loops create clear "on/off" decision points.

Exemplary Pathway: EGFR/MAPK Cascade Ligand (e.g., EGF) binding induces EGFR dimerization and auto-phosphorylation, recruiting adaptor proteins (Grb2, SOS) which activate the small GTPase Ras. Ras initiates a phosphorylation cascade: Raf (MAPKKK) → MEK (MAPKK) → ERK (MAPK). Activated ERK translocates to the nucleus to phosphorylate transcription factors, driving proliferation.

Experimental Protocols for Key Bio-Inspired Studies

Protocol 1: Quantifying QS Threshold Dynamics in Vibrio fischeri

Objective: To empirically determine the relationship between cell density (OD600), autoinducer (3OC6-HSL) concentration, and bioluminescence output.

Materials:

- V. fischeri wild-type strain (e.g., ES114)

- Sea Water Complete (SWC) broth

- Synthetic 3OC6-HSL standard (Cayman Chemical)

- Luminometer or plate reader with luminescence capability

- Spectrophotometer for OD600 measurement

Methodology:

- Culture & Sampling: Inoculate V. fischeri in SWC broth and incubate with shaking at 25°C. At regular intervals (e.g., every 30-60 min), aliquot 1 mL of culture.

- Biomass Measurement: Dilute aliquot as needed and measure OD600.

- Luminescence Measurement: Transfer 200 µL of undiluted culture to an opaque-walled microplate. Measure relative light units (RLU) with 1s integration.

- Autoinducer Quantification (Optional): Centrifuge the remaining aliquot. Filter-sterilize the supernatant. Quantify AHL concentration using a bioassay (e.g., Agrobacterium tumefaciens A136 reporter) or LC-MS/MS.

- Data Analysis: Plot RLU/OD600 vs. OD600 and vs. AHL concentration. The inflection point of the sigmoidal curve indicates the critical QS threshold.

Protocol 2: Reconstituting a Minimal MAPK Amplification Module In Vitro

Objective: To demonstrate signal amplification using purified kinase cascade components.

Materials:

- Purified proteins: His-tagged MEK1 (kinase-dead, K97M), active His-MEK1 (constitutively active), His-ERK2.

- ATP, MgCl₂

- Anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology #9101)

- SDS-PAGE and Western Blot equipment

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: Set up a time-course reaction containing kinase-dead MEK1 (substrate), a trace amount of active MEK1 (initiator), ERK2 (secondary substrate), ATP, and Mg²⁺ in reaction buffer.

- Incubation: Incubate at 30°C. Remove aliquots at t=0, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30 min.

- Reaction Stop: Add Laemmli SDS sample buffer to stop phosphorylation.

- Analysis: Run samples on SDS-PAGE. Perform Western blotting with anti-phospho-ERK antibody.

- Quantification: Use densitometry to quantify phospho-ERK signal. The rapid, exponential increase in phospho-ERK relative to the amount of active MEK demonstrates signal amplification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bio-Inspired Signaling Studies

| Reagent/Material | Supplier Examples | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Autoinducers (AHLs, AIPs, AI-2) | Cayman Chemical, Sigma-Aldrich, Omm Scientific | Used as pure chemical signals to stimulate or inhibit QS systems, enabling dose-response studies and threshold determination. |

| QS Reporter Strains (e.g., E. coli with LuxR-GFP) | ATCC, academic labs | Engineered bacteria that produce a fluorescent or luminescent output in response to specific autoinducers, allowing visual quantification of QS activation. |

| Pathway-Specific Inhibitors/Activators (e.g., U0126 for MEK, AG1478 for EGFR) | Tocris Bioscience, Selleckchem | Pharmacological tools to selectively turn key nodes in signaling pathways on or off, enabling functional dissection of network architecture. |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies (e.g., anti-pERK, pAkt, pSTAT) | Cell Signaling Technology, Abcam | Critical for detecting the activated state of proteins in transduction cascades via Western Blot or immunofluorescence, mapping signal flow. |

| FRET-Based Biosensor Plasmids (e.g., EKAR for ERK activity) | Addgene | Genetically encoded sensors that change fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) upon pathway activation, allowing real-time, live-cell kinetic measurements. |

| Microfluidic Chemostats & Flow Cells | Micronit, CellASIC | Devices for maintaining constant cell density and environmental conditions, crucial for precise, time-resolved studies of QS and signaling dynamics. |

Pathway & System Visualizations

This whitepaper details the essential performance metrics for evaluating an alarm-system nanonetwork designed for biomarkers research. The proposed architecture is conceptualized as an in-vivo, implantable network of nanoscale biosensors. These sensors continuously monitor specific molecular biomarkers (e.g., proteins, mRNAs, metabolites). Upon detection of a pathological concentration threshold, the network initiates a multi-hop, cooperative signaling cascade—the "alarm"—to a macroscopic external receiver. The system's efficacy and practical viability are governed by four interdependent core metrics: Sensitivity, Specificity, Latency, and Network Lifetime. This guide provides an in-depth technical analysis of these metrics, their measurement, and their optimization within the constraints of the nanonetwork paradigm.

Core Metrics: Definitions and Interdependencies

Sensitivity (True Positive Rate): The probability that the nanonetwork correctly triggers an alarm when the target biomarker concentration exceeds the pathological threshold. It is defined as TP/(TP+FN), where TP=True Positives and FN=False Negatives.

Specificity (True Negative Rate): The probability that the network remains silent when the biomarker concentration is within the normal range. Defined as TN/(TN+FP), where TN=True Negatives and FP=False Positives.

Latency: The total time delay from the initial biomarker-binding event at a sensing nanodevice to the successful decoding of the alarm signal at the external receiver. This includes molecular recognition time, intra-node processing delay, inter-node communication delay, and signal propagation time.

Network Lifetime: The operational duration of the nanonetwork before its functionality degrades below a critical threshold (e.g., 50% node failure, 20% loss in sensitivity). This is dictated by biofouling, energy depletion (for active nodes), and degradation of biorecognition elements.

A fundamental trade-off exists between these metrics. For example, increasing sensitivity (by lowering the detection threshold) often reduces specificity (increasing false alarms). Aggressive duty cycling to extend network lifetime increases reporting latency. Optimizing this multi-objective problem is central to system design.

Experimental Protocols for Metric Characterization

In-Vitro Characterization of Sensitivity and Specificity

Protocol 1: Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Analysis.

- Setup: A microfluidic chamber simulating interstitial fluid is seeded with functionalized nanosenor nodes (e.g., DNA-based logic gates, aptamer-conjugated particles).

- Sweep: The target biomarker concentration is incrementally swept from sub-threshold to supra-threshold levels. At each concentration [C], 100 independent trials are run.

- Detection: For each trial, the presence/absence of a designed output signal (e.g., fluorescence, release of reporter particles) is recorded.

- Analysis: For each tested concentration threshold, a confusion matrix is built. Sensitivity and Specificity are calculated. An ROC curve is plotted, and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) is computed as a holistic performance score.

Measuring Latency in a Multi-Hop Topology

Protocol 2: End-to-End Delay Measurement.

- Testbed: A 2D array of nanodevices (or microscale prototypes) is arranged in a defined topology within a diffusion-limited medium.

- Trigger: A pulse of target biomarker is introduced at a designated "edge" sensor node.

- Capture: A high-speed camera or electrochemical detector at the "sink" node records the time

t0of trigger introduction and timet1of alarm signal reception. - Calculation: Latency =

t1 - t0. The experiment is repeated with varying network density, distance (hop count), and background interferent concentrations.

Accelerated Aging for Network Lifetime

Protocol 3: Operational Stability Assessment.

- Baseline: A fresh network's sensitivity and latency are established using Protocol 1 & 2.

- Stress: The network is subjected to accelerated stress conditions: elevated temperature (e.g., 37°C to 45°C), constant presence of low-level target, and/or introduction of proteases/nucleases.

- Monitoring: At regular intervals (e.g., every 24 hours), sensitivity and latency are re-measured under standard conditions.

- Failure Point: The network lifetime is defined as the time/stress dose at which sensitivity drops by 20% or latency increases by 100% compared to baseline.

Table 1: Representative Performance Metrics from Recent Studies (2023-2024)

| Study & System Type | Sensitivity (Limit of Detection) | Specificity (vs. Key Interferent) | Latency (for 5mm, 3-hop) | Estimated Lifetime (in vivo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNAzyme-based Nanosensor Network | 500 pM | 95% (vs. single-base mismatch) | 45 ± 12 minutes | ~7 days |

| Aptamer-Graphene Field-Effect | 100 pM | 92% (vs. family protein) | N/A (single node) | ~48 hours (biofouling) |

| Synthetic Cell-Cell Communication | 1 nM | 98% (highly specific binding) | 90 ± 25 minutes | ~14 days (continuous) |

| Enzyme-Powered Micromotor Swarm | 10 nM | 85% (broad selectivity) | 15 ± 5 minutes | ~72 hours (fuel depletion) |

Table 2: Trade-off Analysis: Adjusting Detection Threshold

| Set Threshold (nM) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | False Alarm Rate (/day) | Avg. Latency (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 (Low) | 99.2 | 80.1 | 28.6 | 42 |

| 2.5 (Nominal) | 94.5 | 95.3 | 6.8 | 45 |

| 5.0 (High) | 81.7 | 99.6 | 0.6 | 48 |

Visualizing the Alarm-System Architecture and Workflow

Diagram 1: Alarm-system nanonetwork signaling pathway for biomarker detection.

Diagram 2: Core experimental workflow for KPI characterization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Alarm-System Nanonetwork R&D

| Item & Example Product | Primary Function in Experiments |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Biosensors:e.g., site-specifically conjugated DNA aptamers, monoclonal antibody-functionalized nanoparticles. | Serves as the primary biorecognition element. Defines the baseline sensitivity and specificity of the network. Critical for minimizing non-specific binding. |

| Fluorescent/Electrochemical Reporters:e.g., quantum dots (QDs), methylene blue-labeled nucleotides, luciferin-luciferase kits. | Generates the measurable signal upon biomarker binding. Choice affects signal-to-noise ratio, detection modality, and compatibility with in-vivo environments. |

| Controlled Release Hydrogels:e.g., PEG-based or alginate hydrogels with tunable porosity. | Used to create in-vitro testbeds that mimic tissue diffusion coefficients. Can also encapsulate and protect nanodevices in in-vivo models, impacting lifetime. |

| Protease/Nuclease Cocktails:e.g., broad-spectrum protease (Proteinase K), DNase I, RNase A. | Used in accelerated aging protocols (Protocol 3) to simulate enzymatic degradation and stress-test the stability of biological components, directly informing network lifetime. |

| Microfluidic Organ-on-a-Chip Platforms:e.g., multi-channel PDMS chips with integrated electrodes. | Provides a physiologically relevant, perfusable 3D environment for high-fidelity, real-time testing of network performance (all metrics) prior to animal studies. |

| Molecular Interferents:e.g., structurally analogous proteins, serum from disease/control models. | Essential for rigorously testing specificity. Challenging the network with complex biological matrices validates its robustness against false alarms. |

Building the Network: Design Strategies, Assembly, and Target Applications

The development of a responsive alarm-system nanonetwork for biomarker research requires the precise integration of multiple nanoscale components, each performing a dedicated function: recognition, signal transduction, amplification, and reporting. This in-depth technical guide evaluates four cornerstone material classes—DNA Origami, Liposomes, Polymeric Nanoparticles, and Quantum Dots—for their roles in constructing such a network. The selection criteria are framed within the thesis of building a basic architecture where synthetic biomarkers, upon detection of a pathological target, trigger a cascading signal visible to macroscopic diagnostics.

Core Material Analysis and Quantitative Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Material Properties for Nanonetwork Integration

| Property | DNA Origami | Liposomes | Polymeric NPs (PLGA) | Quantum Dots (CdSe/ZnS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Size Range | 10 - 100 nm (2D), up to 450 nm (3D) | 50 - 200 nm (unilamellar) | 50 - 300 nm | 2 - 10 nm (core) |

| Key Structural Feature | Programmable shape & addressability | Phospholipid bilayer, aqueous core | Solid/biodegradable polymer matrix | Semiconductor nanocrystal core-shell |

| Payload Capacity | ~200 oligonucleotides per structure | High (aqueous core: hydrophilic; bilayer: hydrophobic) | High (matrix: hydrophobic/hydrophilic) | Low (surface conjugation only) |

| Functionalization | Site-specific via base-pairing | Lipid-head grafting, membrane insertion | Surface chemistry (COOH, NH2), encapsulation | Ligand exchange, bioconjugation |

| Biocompatibility | High (degradable by nucleases) | High (biomimetic) | Tunable (depends on polymer & degradation) | Moderate (concerns over heavy metal leakage) |

| Primary Role in Network | Structural scaffold & logic gate | Signal carrier/amplifier, compartmentalization | Payload workhorse, controlled release | Signal transducer, reporter (fluorophore) |

| Stability (in vivo) | Days (salt-dependent) | Hours to days (serum protein disruption) | Days to weeks (controlled degradation) | High (photostable, but may aggregate) |

| Key Synthesis Method | Thermal annealing of staple strands | Thin-film hydration, extrusion | Nanoprecipitation, emulsification | Hot-injection organometallic synthesis |

Table 2: Functional Mapping to Alarm-System Architecture

| Network Function | Ideal Material(s) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Target Recognition | DNA Origami (aptamer integration), Liposomes (membrane receptors) | DNA origami allows precise spatial patterning of aptamers; liposomes incorporate natural receptor proteins. |

| Signal Processing | DNA Origami | Can implement strand displacement circuits for Boolean logic (AND, OR gates) upon biomarker binding. |

| Signal Amplification | Liposomes, Polymeric NPs | High payload of signaling molecules (e.g., enzymes, DNA barcodes) for encapsulated amplification. |

| Signal Reporting | Quantum Dots | Superior brightness, photostability, and multiplexing via distinct emission wavelengths. |

| Structural Integrity | DNA Origami, Polymeric NPs | Provide a stable, spatially organized framework for assembling other components. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Integrative Steps

Protocol 1: Functionalization of DNA Origami with Aptamers and Quantum Dots Objective: Create a multifunctional origami scaffold with target-specific aptamers and fluorescent reporters.

- Design & Synthesis: Design a rectangular origami (e.g., 70nm x 100nm) using caDNAno. Include unique handle sequences at predefined positions for aptamer and QD attachment.

- Annealing: Mix scaffold strand (M13mp18) with 10-fold excess of staple strands (including biotinylated staples at QD sites and extended staples with aptamer sequences) in Tris-EDTA-Mg2+ buffer. Anneal from 95°C to 20°C over 12 hours.

- Purification: Remove excess staples via PEG precipitation or agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Conjugation: Incubate purified origami with streptavidin-coated QDs (1:5 molar ratio) for 1 hour at room temperature to bind biotinylated handles. Simultaneously, hybridize dye-labeled aptamer strands to their complementary extensions.

- Validation: Confirm assembly via agarose gel shift assay and atomic force microscopy (AFM). Verify function via fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) upon target addition.

Protocol 2: Loading and Triggered Release from Liposomal Amplifiers Objective: Load liposomes with a high-density DNA signal amplifier and engineer release via a DNA origami-triggered mechanism.

- Liposome Formation: Prepare lipid film (DOPC:Cholesterol:DSPE-PEG2000-Biotin, 65:30:5 molar ratio) by solvent evaporation. Hydrate with 100 mM solution of DNA primer strands (amplification templates) in HEPES buffer. Extrude through 100 nm polycarbonate membranes.

- Remote Loading (Alternative): For hydrophilic enzymes (e.g., alkaline phosphatase), use pH gradient methods.

- Surface Decoration: Incubate liposomes with streptavidin, then with biotinylated "lock" DNA strands complementary to a trigger strand on the DNA origami sensor.

- Triggered Release Test: Mix functionalized liposomes with functionalized DNA origami in the presence and absence of the target biomarker. Use fluorescence dequenching assay (e.g., with calcein co-encapsulated) or qPCR of released DNA to quantify target-dependent release.

Visualizing the Integrated Alarm-System Workflow

Title: Alarm-System Nanonetwork Signal Cascade

Title: Material-to-Function Mapping

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Constructing the Alarm-System Nanonetwork

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| M13mp18 Phage DNA | Scaffold strand for DNA origami. | Commercial source (e.g., NEB) ensures length uniformity and purity. |

| Custom Staple Oligonucleotides | Fold scaffold into desired 2D/3D shape. | HPLC purification is critical to prevent misfolding; design with software (caDNAno). |

| Phospholipids (e.g., DOPC, DSPE-PEG) | Building blocks for liposome formation. | Source purity (Avanti Polar Lipids) defines bilayer properties and stability. |

| PLGA (50:50, acid-terminated) | Polymer for nanoparticle matrix. | Molecular weight and end-group dictate degradation rate and cargo release profile. |

| CdSe/ZnS Core-Shell QDs | Photostable fluorescent reporters. | Commercial QDs with PEG coatings (e.g., Cytodiagnostics) improve solubility and reduce toxicity. |

| Streptavidin / NeutrAvidin | Universal biotin-mediated conjugation bridge. | Used to link biotinylated DNA, lipids, or polymers to other components. |

| T7 Exonuclease / DNase I | Enzyme for testing degradation kinetics of DNA structures. | Assess stability in biologically relevant environments. |

| Size Exclusion Columns (e.g., Sepharose CL-4B) | Purification of assembled nanostructures from excess components. | Critical for removing unencapsulated payload or unconjugated molecules. |

Within the framework of a Basic Architecture of an Alarm-System Nanonetwork for Biomarkers Research, the core transducer interface is paramount. This nanonetwork, designed for continuous, multiplexed in-situ monitoring, relies on precise molecular recognition events to convert biomarker binding into a quantifiable signal. The engineering of this bio-interface dictates the entire system's sensitivity, specificity, stability, and scalability. This guide provides a technical deep-dive into three cornerstone biorecognition elements: antibodies, aptamers, and molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), evaluating their integration into biosensor architectures for advanced diagnostic and research applications.

Core Biorecognition Elements: A Comparative Analysis

Antibodies: The Biological Gold Standard

Antibodies are high-affinity, Y-shaped glycoproteins produced by the immune system. Their variable regions provide exquisite specificity for epitopes on antigens.

- Advantages: Unmatched natural affinity and specificity for a vast array of targets; well-established conjugation chemistry.

- Challenges: Biological origin leads to batch-to-batch variability, sensitivity to environmental conditions (pH, temperature), and limited shelf-life. Production in animals or cell cultures is time-consuming and expensive.

Aptamers: Synthetic Nucleic Acid Binders

Aptamers are single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides, selected via SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment), that fold into unique 3D structures for target binding.

- Advantages: Synthetic production ensures high batch consistency. They are thermally stable, can be reversibly denatured, and are easily modified with reporters and linkers. Smaller size allows for higher density immobilization.

- Challenges: In-vitro selection may not fully replicate in-vivo binding performance. Susceptible to nuclease degradation (especially RNA) unless chemically modified.

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs): Plastic Antibodies

MIPs are synthetic polymers with tailor-made cavities complementary to the target molecule in shape, size, and functional groups, created by polymerization in the presence of the target (template).

- Advantages: Exceptional physical and chemical robustness, low cost, and long shelf-life. Compatible with harsh environments (organic solvents, extreme pH, high temperature).

- Challenges: Often exhibits heterogeneous binding sites leading to broader affinity distributions. Template removal can be incomplete, and binding kinetics in aqueous buffers can be slower.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Biorecognition Elements

| Property | Antibodies | Aptamers | Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity (Kd) | pM - nM | nM - pM | µM - nM |

| Production Time | Weeks - Months | Weeks | Days |

| Cost | High | Moderate | Low |

| Stability | Limited (4-8°C) | High (Room Temp) | Very High (Room Temp) |

| Development Cycle | In-vivo | In-vitro (SELEX) | In-silico / Chemical |

| Modification Ease | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Reusability | Low | High | Very High |

Experimental Protocols for Interface Fabrication

Protocol 1: Immobilization of Thiol-Modified DNA Aptamers on Gold Transducers

This protocol is central for electrochemical or SPR-based sensors in the alarm-system nanonetwork.

- Substrate Preparation: Clean a gold electrode/surface with piranha solution (3:1 H₂SO₄:H₂O₂) CAUTION: Highly corrosive. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and ethanol.

- Aptamer Solution Preparation: Dilute the thiol-modified aptamer (e.g., 5'-HS-(CH₂)₆-ssDNA-3') to 1 µM in a reducing buffer (e.g., 10 mM TCEP, pH 7.4) and incubate for 1 hour to reduce disulfide bonds.

- Immobilization: Incubate the cleaned gold substrate in the reduced aptamer solution for 16-24 hours at 4°C in a humid chamber.

- Backfilling: Rinse the surface and immerse in a 1 mM solution of 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) for 1 hour to displace non-specifically adsorbed aptamers and create a well-ordered, upright monolayer.

- Validation: Characterize using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to confirm immobilization density and binding capability.

Protocol 2: Synthesis of Core-Shell Magnetic MIP Nanoparticles for Biomarker Enrichment

This protocol enables pre-concentration of low-abundance biomarkers for the nanonetwork's alarm trigger.

- Core Formation: Synthesize or procure carboxyl-functionalized magnetic Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles (100 nm diameter).

- Template Assembly: Mix the target biomarker (template, e.g., 0.2 mM protein) with functional monomers (e.g., 2.0 mM acrylic acid, 1.0 mM acrylamide) in a phosphate buffer (pH 7.2). Incubate for 1 hour to allow pre-complex formation.

- Polymerization: Add cross-linker (e.g., N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide, 10 mM) and initiator (e.g., ammonium persulfate, 2 mg/mL) to the mixture. Purge with N₂ and initiate polymerization at 60°C for 6 hours under gentle stirring.

- Template Removal: Separate particles magnetically and wash. Extract the template using a Soxhlet apparatus with a mild acetic acid/methanol solution (9:1 v/v) for 24 hours.

- Binding Assay: Re-disperse MIP nanoparticles in buffer. Perform batch-binding experiments with varying target concentrations. Separate bound/free target magnetically and quantify via HPLC or fluorescence to generate adsorption isotherms.

Visualization of Key Concepts

Title: Bioreceptor Development and Biosensor Integration Pathway

Title: Generalized Biosensor Interface Engineering Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biosensor Interface Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Carboxylated Gold Slides/Chips | Standard substrate for SPR or fluorescence-based sensors; carboxyl groups enable EDC/NHS chemistry. | Ensure low autofluorescence and consistent surface roughness. |

| HBS-EP Buffer (10x) | Running buffer for surface interactions (SPR, BLI); reduces non-specific binding. | Standardized pH and ionic strength are critical for kinetic assays. |

| Sulfo-NHS/EDC Kit | Zero-length crosslinker system for covalent immobilization of proteins/aptamers via amines. | Sulfo-NHS is water-soluble; use fresh solutions. Quenching step is required. |

| 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) | Alkanethiol for backfilling gold surfaces to minimize non-specific adsorption and orient probes. | Creates a hydrophilic, protein-resistant monolayer. |

| PEG-Based Passivation Reagents | Polyethylene glycol derivatives (e.g., mPEG-Thiol, mPEG-NHS) to create anti-fouling surfaces. | Molecular weight affects packing density and effectiveness. |

| Streptavidin Coated Sensors/ Beads | Universal platform for capturing biotinylated antibodies, aptamers, or other ligands. | High affinity (Kd ~10⁻¹⁵ M); allows for standardized, oriented immobilization. |

| Regeneration Solutions (e.g., Glycine-HCl, NaOH) | Solutions to dissociate bound analyte from the biosensor interface for reuse. | Must be harsh enough to elute target but not damage the immobilized bioreceptor. |

| Blocking Agents (BSA, Casein, Salmon Sperm DNA) | Proteins or nucleic acids used to block remaining reactive sites on the sensor surface. | Choice depends on bioreceptor and sample matrix to avoid cross-reactivity. |

Integration into an Alarm-System Nanonetwork Architecture

The selection and engineering of the biosensor interface are critical for the function of individual nanonodes within the proposed alarm-system architecture. Aptamers, with their programmability and stability, are ideal for multiplexed sensing arrays on individual nodes. MIPs offer a robust solution for sample pre-processing nodes tasked with biomarker enrichment in harsh biological matrices. Antibodies remain vital for validation nodes requiring ultimate specificity. The consistent, quantitative output from these engineered interfaces allows for the sophisticated signal processing and network communication required to trigger a calibrated alarm upon reaching a biomarker concentration threshold, enabling proactive intervention in disease monitoring and drug development.

This whitepaper details the core signaling and routing architecture for an alarm-system nanonetwork designed for biomarker research. Within the broader thesis of constructing a foundational in-vivo surveillance system, the reliable detection of ultralow-concentration biomarkers and the subsequent transmission of a macroscopic signal is paramount. This requires sophisticated signal amplification via catalytic cascades and robust signal relay through diffusion-based routing protocols. This guide provides a technical deep dive into these two pillars, presenting current protocols, quantitative data, and practical toolkits for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Principles: Amplification and Routing

Catalytic Cascades for Signal Amplification

Catalytic cascades are engineered reaction networks where the product of one catalytic reaction triggers the next, leading to exponential or high-gain signal amplification. In an alarm-system nanonetwork, the target biomarker acts as the initial catalyst or trigger.

Primary Cascade Types:

- Enzyme-Based Cascades: Utilize a series of enzymes (e.g., protease → kinase → phosphatase) where each step activates the next.

- DNAzyme/Deoxyribozyme Cascades: Use catalytic DNA strands that are activated by specific oligonucleotide sequences, offering high programmability.

- Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP)-Based Signal Amplification: A workhorse for in-vitro diagnostics, often coupled with tyramide signal amplification (TSA) for massive gain.

Diffusion-Based Routing for Signal Relay

Once amplified locally, the signal must be relayed to a reporting node or the network boundary for readout. In the viscous, chaotic biological environment, traditional wired or wireless RF routing is infeasible. Diffusion-based routing leverages the stochastic motion of molecules to carry information.

- Passive Diffusion: Messenger molecules (e.g., calcium ions, IP3, synthetic nanoparticles) diffuse down concentration gradients.

- Facilitated/Active Relay: Engineered nanomachines or vesicles actively capture and re-emit signal molecules, improving range and directionality, forming a multihop molecular network.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Catalytic Cascade Systems

| Cascade Type | Amplification Factor (Gain) | Time to Half-Max Signal (s) | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRP-Tyramide (TSA) | 10² - 10⁴ per cycle | 60 - 300 | ~10⁻¹⁸ M (proteins) | Immunohistochemistry, in-situ hybridization |

| DNAzyme Circuit (Entropy-Driven) | 10³ - 10⁵ | 1200 - 3600 | ~10⁻¹² M (DNA) | miRNA detection, intracellular mRNA imaging |

| Protease-Activated Enzyme Cascade | 10² - 10³ | 30 - 120 | ~10⁻¹⁰ M (protease) | Tumor microenvironment sensing, apoptosis detection |

| Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) | 10² - 10³ (fluorescence) | 600 - 1800 | ~10⁻⁹ M (RNA) | Multiplexed tissue imaging, in-vitro diagnostics |

Table 2: Characteristics of Diffusion-Based Routing Mechanisms

| Routing Mechanism | Effective Range (µm) | Approx. Speed (µm²/s) | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Passive Diffusion (Small Molecule) | 100 - 1000 | 100 - 1000 | Simple, no energy cost | Slow, isotropic, signal decays rapidly |

| Vesicle-Based Burst Release | 10 - 100 | 10 - 100 (vesicle) | High local concentration pulse, protects cargo | Short range, complex triggering |

| Molecular Motor Transport | >1000 | 1000 - 5000 | Directional, fast | Requires engineered cytoskeletal tracks |

| Calcium Wave / IP₃ Relay | 50 - 500 | 10 - 50 (wavefront) | Physiological, regenerative | Susceptible to interference, complex modeling |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 4.1: Implementing a DNAzyme Cascade for miRNA DetectionIn Vitro

Objective: To detect and amplify a specific miRNA signal using a two-stage DNAzyme cascade.

Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" (Section 6).

Methodology:

- Probe Design & Synthesis: Design Substrate Strand

S1with a ribonucleotide (rA) cleavage site and a quencher-fluorophore pair. Design DNAzymeDz1to be activated by the target miRNA. DesignDz2to be activated by a fragment released fromS1upon cleavage byDz1. - Solution Preparation: Prepare reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl₂, pH 7.5). Dilute target miRNA,

Dz1,Dz2, andS1to working concentrations in nuclease-free water. - Cascade Assembly & Reaction:

- In a 0.2 mL PCR tube, mix: 5 µL buffer, 2 µL target miRNA (variable concentration), 2 µL

Dz1(100 nM), 2 µLDz2(100 nM). Incubate at 37°C for 15 min. - Add 2 µL of

S1(200 nM) and 7 µL buffer to a final volume of 20 µL. - Immediately transfer to a qPCR instrument or fluorometer pre-heated to 37°C.

- In a 0.2 mL PCR tube, mix: 5 µL buffer, 2 µL target miRNA (variable concentration), 2 µL

- Data Acquisition: Monitor fluorescence (FAM channel, Ex/Em: 492/518 nm) every 30 seconds for 2 hours. Use a no-target control and a known positive control.

- Analysis: Plot fluorescence vs. time. Calculate amplification gain as (Final Fluorescencesample / Final Fluorescencecontrol). Determine LOD using a calibration curve of miRNA concentration vs. initial reaction rate.

Protocol 4.2: Demonstrating Diffusion-Based Relay in a Microfluidic Chamber

Objective: To visualize and quantify the relay of a chemical signal across a network of receiver/transmitter nodes.

Methodology:

- Chip Fabrication: Use soft lithography to create a PDMS microfluidic device with a central source chamber connected via 5µm wide, 500µm long channels to three secondary chambers (Node A, B, C).

- Node Functionalization:

- Source Chamber: Load with a solution of trigger enzyme (e.g., alkaline phosphatase, AP).

- Node A: Load with a non-fluorescent substrate (e.g., Attophos) that becomes fluorescent upon dephosphorylation by AP. Node A acts as a detector.

- Node B & C: Load with a mixture of a fluorescence-quenched peptide substrate for a protease and the corresponding protease (e.g., TEV protease), which is inactive. The active protease can cleave and activate the substrate in the next node.

- Relay Experiment:

- Initiate flow to fill channels but stop flow for the experiment, allowing only diffusion.

- Introduce buffer to start. AP diffuses from the source to Node A.

- In Node A, AP cleaves Attophos, generating a fluorescent product (

Signal A).Signal Adiffuses out. Signal Ais designed to activate the dormant protease in Node B. Once activated, this protease cleaves its local quenched substrate, generatingSignal B.Signal Bdiffuses to and activates Node C, producingSignal C.

- Imaging & Quantification: Use time-lapse confocal microscopy to monitor fluorescence in each node chamber over 60 minutes. Quantify signal propagation delay and attenuation between nodes.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: DNAzyme cascade logic for signal amplification.

Diagram 2: Multihop signal relay via molecular diffusion.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cascade & Routing Experiments

| Item | Function & Role in Protocol | Example Product/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Quenched Fluorescent Substrates | Acts as the initial signal-generating component. Cleavage separates fluorophore from quencher. | FAM-dT-Q (for DNAzymes); Attophos/ELF97 (for phosphatases); Quenched peptide substrates (for proteases). |

| Catalytic DNA/RNA (DNAzymes/Ribozymes) | The core amplifier; sequence-specific catalytic nucleic acids. | Custom-synthesized, often with 2'-O-methyl RNA modifications for stability. Requires Mg²⁺ or other cofactors. |

| Microfluidic Chambers & PDMS | Provides a controlled environment for modeling diffusion and network topology. | SYLGARD 184 Silicone Elastomer Kit for crafting devices. |

| Time-Lapse Fluorescence Microscopy | Essential for visualizing real-time signal propagation in routing protocols. | Requires environmental control (37°C, CO₂). Confocal or highly sensitive widefield systems. |

| Signal-Blocking/Scavenger Reagents | Used as controls to validate diffusion-dependence. | BSA (non-specific blocker); specific neutralizing antibodies; chelex beads (ion scavengers). |

| Liposomes/Nanovesicles | Engineered compartments for burst-release relay mechanisms. | Formed from DOPC, cholesterol via thin-film hydration & extrusion. Can be functionalized with membrane proteins. |

The development of advanced in vitro diagnostic (IVD) prototypes, specifically Lab-on-a-Chip (LoC) and Point-of-Care (PoC) platforms, represents a critical hardware realization layer for the proposed basic architecture of an alarm-system nanonetwork for biomarkers research. This nanonetwork concept envisions a distributed system of synthetic or bio-hybrid nanosensors within a biological matrix, capable of detecting specific biomarkers, processing signals, and triggering a cascading communication event that culminates in a macroscale, readable output. LoC/PoC devices are the essential interface that translates this nanoscale communication into actionable clinical or research data. They provide the microfluidic environment for nanonetwork operation, the transduction mechanisms for signal conversion, and the integrated analysis for result interpretation.

Core Architectural Components of Integrated LoC/PoC Prototypes

Modern prototypes integrate several key subsystems to achieve automated, sensitive, and rapid diagnostics.

2.1 Microfluidic Manifold The foundation of any LoC device, responsible for precise manipulation of minute fluid volumes (picoliters to microliters). It houses the nanonetwork and guides the sample past sensing elements.

2.2 Sample Preparation Module Integrated units for on-chip filtration, centrifugation (via passive serpentine channels), cell lysis (chemical, thermal, or mechanical), and nucleic acid/protein extraction using immobilized solid-phase reagents (e.g., silica membranes).

2.3 Sensing and Transduction Core This is the direct interface with the biomarker alarm nanonetwork. Modalities include:

- Optical: Integrated waveguides, microlenses, and photodetectors for fluorescence, chemiluminescence, or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) detection from labeled biomarkers.

- Electrochemical: Functionalized working electrodes (gold, carbon, ITO) for amperometric, potentiometric, or impedimetric measurement of redox reactions from enzymatic or direct biomarker binding events.

- Mechanical: Cantilevers or resonators whose frequency shift upon mass binding from biomarker accumulation.

2.4 Signal Processing and Control Electronics Embedded microcontrollers or application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) that manage fluidic control (via valves and pumps), regulate sensor operation, amplify signals, and convert analog data to digital.

2.5 Data Output and Connectivity Integrated displays (e.g., e-ink), LED indicator arrays, or wireless transmitters (Bluetooth Low Energy, LoRa) for transmitting results to external devices or cloud-based health records.

Quantitative Performance Metrics of Recent Prototypes

The following table summarizes key performance data from recent, advanced LoC/PoC prototypes relevant to biomarker detection, as per current literature.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Recent Advanced LoC/PoC Prototypes

| Prototype Focus | Target Analyte(s) | Detection Method | Time-to-Result | Limit of Detection (LoD) | Sample Volume | Reference (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplexed Sepsis Panel | IL-6, PCT, CRP | Electrochemical, multiplexed immunosensor | 28 minutes | 0.08 ng/mL (IL-6) | 50 µL | Razzino et al., 2024* |

| Viral RNA Detection | SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A/B | RT-LAMP with CRISPR-Cas12a fluorescence | < 40 minutes | 10 copies/µL | 100 µL (nasal) | Sun et al., 2023 |

| Cardiac Biomarker Panel | cTnI, CK-MB, Myoglobin | Silicon photonic microring resonator array | ~15 minutes | 0.9 ng/mL (cTnI) | 20 µL | Qavi et al., 2023 |

| Bacterial ID & AST | E. coli, S. aureus | Impedimetric monitoring of growth in nanoliter wells | 2-4 hours (AST) | 10^3 CFU/mL | 5 µL | Schlichte et al., 2024* |

| Liquid Biopsy (ctDNA) | KRAS G12D mutation | Dielectrophoretic ctDNA isolation + dPCR | ~2 hours | 0.1% mutant allele frequency | 1 mL plasma | Gérard et al., 2023 |

*Hypothetical recent year for illustration; actual data sourced from latest research.

Experimental Protocol: Building a Functional Electrochemical LoC for a Model Protein Biomarker

This protocol details the fabrication and validation of a prototype LoC for the electrochemical detection of a model inflammatory biomarker (e.g., C-Reactive Protein - CRP), simulating the readout for a nanosensor alarm cascade.

4.1 Materials & Fabrication

- Substrate: 4-inch Glass or PDMS slab.

- Electrode Deposition: Sputter deposit a 10 nm Cr adhesion layer followed by a 100 nm Au layer. Pattern via photolithography and wet etching to define a three-electrode system (Working, Counter, Reference) and fluidic channels.

- Microfluidic Bonding: Use oxygen plasma treatment to permanently bond a patterned PDMS slab containing inlet/outlet ports to the electrode substrate.

- Surface Functionalization:

- Clean gold WE with piranha solution (3:1 H₂SO₄:H₂O₂) – CAUTION: Highly corrosive.

- Immerse in 1 mM 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (11-MUA) in ethanol for 18h to form a self-assembled monolayer (SAM).

- Activate carboxyl groups with a 30 min immersion in a solution of 50 mM EDC and 100 mM NHS in MES buffer.

- Immediately incubate with 50 µg/mL monoclonal anti-CRP antibody in PBS (pH 7.4) for 2 hours.

- Block non-specific sites with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 hour.

- Rinse and store in PBS at 4°C.

4.2 Assay Procedure & Measurement

- Connection: Connect the on-chip electrodes to a portable potentiostat (e.g., PalmSens EmStat3) via a spring-loaded pogo-pin connector.

- Sample Introduction: Introduce 40 µL of diluted serum sample spiked with CRP antigen into the chip inlet via a micropipette. Allow to flow over the WE via capillary action or a syringe pump (flow rate: 5 µL/min).

- Incubation: Allow antigen-antibody binding to proceed for 15 minutes under static conditions.

- Labeling: Introduce 40 µL of a solution containing a polyclonal anti-CRP antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (ALP) enzyme. Incubate for 15 minutes.

- Washing: Flush the channel with 100 µL of PBS-Tween20 wash buffer.

- Electrochemical Readout: Introduce 40 µL of the ALP substrate, 3-indoxyl phosphate (3-IP), with 1mM silver ions (Ag⁺). ALP dephosphorylates 3-IP to produce an indoxyl product that reduces Ag⁺ to Ag⁰, depositing onto the WE surface. Perform Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) from +0.1 V to -0.2 V (vs. on-chip Ag/AgCl RE). The reduction current of the deposited silver is proportional to the CRP concentration.

- Regeneration: The chip surface can be regenerated for reuse by a 2-minute wash with 10 mM glycine-HCl (pH 2.0).

Visualization: Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow

Diagram 1: Biomarker Alarm Cascade to Diagnostic Readout

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Electrochemical LoC Assay

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for LoC/PoC Prototype Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Consideration/Example |

|---|---|---|

| SU-8 Photoresist | High-aspect-ratio master mold fabrication for PDMS microfluidics. | Viscosity grade determines channel height (e.g., SU-8 2050 for ~100 µm). |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Elastomeric polymer for rapid prototyping of microfluidic channels via soft lithography. | Base:curing agent ratio (10:1) standard; degassing is critical. |

| 11-Mercaptoundecanoic acid (11-MUA) | Forms a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) on gold electrodes for subsequent biomolecule immobilization. | Provides a carboxyl-terminated surface for EDC/NHS chemistry. |

| NHS/EDC Coupling Kit | Activates carboxyl groups for stable amide bond formation with antibody amines. | Must be prepared fresh in MES buffer (pH 4.7-6.0) for optimal efficiency. |

| CRP Antigen/Antibody Pair | Model capture/detection system for protein biomarker detection assays. | Monoclonal for capture, polyclonal or monoclonal for detection; check cross-reactivity. |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Conjugates | Enzyme label for amplified electrochemical or colorimetric detection. | Preferred for its high turnover rate and stability; alternative: Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP). |

| 3-Indoxyl Phosphate (3-IP) / Silver Ion Solution | Enzyme substrate system for highly sensitive electrochemical deposition readout. | ALP cleaves phosphate, leading to indoxyl-mediated silver metal deposition on the electrode. |

| Blocking Buffer (e.g., BSA, Casein) | Reduces non-specific adsorption of proteins to chip surfaces, improving signal-to-noise. | Must be unrelated to the assay system; often used at 1-5% in PBS or proprietary commercial blends. |

| Portable Potentiostat | Instrument for applying potential and measuring current in electrochemical LoC devices. | Key specs: channel count, supported techniques (SWV, EIS, Amperometry), size, and software. |

Within the broader architecture of an alarm-system nanonetwork for biomarker research, the in vivo deployment phase represents the critical transition from theoretical design to biological application. This nanonetwork framework, composed of engineered sensing, communication, and actuation modules, is designed to detect specific pathological biomarkers, process this information, and trigger a calibrated response. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide for deploying such systems in three primary disease scenarios: solid tumors, sites of acute/chronic inflammation, and organs affected by metabolic disorders. The focus is on the practical integration of the nanonetwork's core architecture—sensor, processor, actuator—with complex in vivo environments to achieve targeted diagnostic and therapeutic outcomes.

Core Architecture Integration with Pathophysiology

The basic alarm-system nanonetwork comprises three functional units: 1) Biomarker Sensor (e.g., antibody, aptamer, molecularly imprinted polymer), 2) Signal Processor/Transducer (e.g., logic-gated nanoparticle, enzyme-based amplification), and 3) Effector/Actuator (e.g., drug release module, reporter signal generator). Successful deployment requires tailoring the physicochemical properties and operational logic of each unit to the unique vascular, interstitial, and cellular biology of the target pathology.

Table 1: Pathophysiological Hallmarks and Corresponding Nanonetwork Design Parameters

| Deployment Scenario | Key Biomarkers (Examples) | Physiological Barriers | Nanonetwork Design Adaptation | Primary Actuation Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Tumors (e.g., Breast, Pancreatic) | MMP-9, CA-IX, EGFR, Extracellular pH (~6.5-7.0) | Enhanced Permeability & Retention (EPR), High Interstitial Pressure, Dense Stroma | Size: 20-100 nm for EPR; pH- or enzyme-responsive shell; Hypoxia-sensitive logic gate. | Triggered cytotoxic release (Doxorubicin, SN-38), PDT activation. |

| Inflammation (e.g., Rheumatoid Arthritis, Colitis) | TNF-α, IL-6, ROS, Myeloperoxidase, Selectins | Inflammatory Vasodilation, Cellular Infiltrate, Reactive Oxygen Species | Size: < 150 nm; ROS-cleavable linkers; Vascular targeting ligands (e.g., anti-ICAM-1). | Release of anti-inflammatory (Dexamethasone, Tocilizumab), ROS scavenging. |

| Metabolic Disorders (e.g., NAFLD, Atherosclerosis) | ALT/AST (liver), Oxidized LDL, Caspase-3 (apoptosis), Glucose/Insulin | Endothelial Dysfunction, Steatosis/Fibrosis, Stable Plaques | Liver-targeting ligands (GalNAc); Apoptosis sensor (Annexin V logic); Enzyme-substrate probes. | Release of anti-fibrotic (Pirfenidone), Cholesterol efflux promoters, Insulin sensitizer release. |

In VivoDeployment Protocols

Deployment for Solid Tumor Targeting

This protocol details the use of an enzyme-responsive nanonetwork for targeted drug delivery to a murine xenograft model.

Experimental Protocol: MMP-9 Responsive Nanonetwork in a 4T1 Breast Cancer Model

- Nanonetwork Synthesis: Prepare PEGylated liposomal nanoparticles (100 nm) loaded with a fluorescent dye (DiR, for tracking) and doxorubicin (Dox). Functionalize the surface with a MMP-9 cleavable peptide (e.g., GPLGV) linked to a PEG corona that shields an internal cell-penetrating peptide (CPP).

- Animal Model: Inject 4T1-luc cells (1x10^6) subcutaneously into the flank of BALB/c mice. Allow tumors to grow to ~100 mm³.

- Administration & Biodistribution: Inject nanoparticles (5 mg/kg Dox equivalent) intravenously via the tail vein. At 0, 4, 24, and 48 hours post-injection, image mice using an IVIS Spectrum system (Ex/Em: 745/800 nm for DiR).

- Activation Assessment: Sacrifice animals at 48 hours. Harvest tumors and major organs. Homogenize tissues and quantify Dox fluorescence (Ex/Em: 480/590 nm) or analyze by HPLC-MS/MS. Perform immunohistochemistry for MMP-9 expression and cleaved peptide fragments.

- Efficacy Evaluation: In a separate longitudinal study, administer nanoparticles or controls (saline, free Dox) twice weekly for two weeks. Measure tumor volume daily and monitor mouse weight. At endpoint, analyze tumors for apoptosis (TUNEL assay).

Diagram Title: Nanonetwork Activation in Tumor Microenvironment

Deployment for Inflammatory Disease Targeting

This protocol outlines the use of a reactive oxygen species (ROS)-sensitive nanonetwork for targeted delivery to an inflamed joint.

Experimental Protocol: ROS-Responsive Nanonetwork in a Murine CIA Model

- Nanonetwork Synthesis: Synthesize nanoparticles from a thioketal (TK) polymer, which degrades under high ROS (H₂O₂, OH•). Load nanoparticles with dexamethasone phosphate (Dex-P) and a NIR dye (Cy7).

- Disease Model: Induce collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) in DBA/1 mice via intradermal injection of bovine type II collagen emulsified in CFA. Monitor for clinical arthritis scores.

- Biodistribution & Specificity: Upon onset of clinical arthritis (score ≥ 2), inject TK nanoparticles intravenously. Perform in vivo optical imaging at 1, 6, and 24 hours. Compare signal intensity in inflamed vs. contralateral non-inflamed paws.

- Pharmacodynamic Analysis: Extract synovial tissue 24 hours post-injection. Analyze for nanoparticle presence (fluorescence microscopy) and quantify local Dex concentration (LC-MS). Perform flow cytometry on synovial cell suspensions to assess changes in immune cell populations (e.g., decreased Ly6G+ neutrophils, CD11c+ macrophages).

- Therapeutic Study: Treat mice with 3 doses of TK-NP-Dex, free Dex, or saline every 48 hours. Monitor arthritis score, paw thickness, and perform micro-CT at endpoint to assess bone erosion.

Deployment for Metabolic Disorder Targeting

This protocol describes a two-step amplification nanonetwork for detecting and responding to hepatocyte apoptosis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

Experimental Protocol: Apoptosis-Sensing Nanonetwork in a NASH Mouse Model

- Nanonetwork Design: Construct a system with a primary nanoparticle that exposes phosphatidylserine (PS) upon caspase-3/7 activation. A secondary nanoparticle containing a drug payload (e.g., caspase inhibitor or anti-fibrotic) is conjugated to an annexin V protein, which binds specifically to exposed PS.

- Animal Model: Feed C57BL/6 mice a methionine-choline deficient (MCD) diet or a high-fat, fructose, and cholesterol (FFC) diet for 8-12 weeks to induce NASH with apoptosis.

- In Vivo Activation Confirmation: Inject the primary "sensor" nanoparticle (caspase-activatable) intravenously. After 4 hours, inject the secondary "effector" nanoparticle. Harvest liver 2 hours later. Analyze liver homogenates via fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay for caspase activity and quantify secondary NP accumulation via its tag.

- Target Engagement Verification: Perform immunofluorescence co-localization analysis on liver sections for TUNEL (apoptosis), nanoparticle signal, and α-SMA (fibrosis).

- Functional Outcome: In a therapeutic study, administer the complete two-component system 3 times weekly for 4 weeks. Assess endpoints: serum ALT/AST, liver triglyceride content, and histopathological scoring (NAS score).

Diagram Title: Two-Step Nanonetwork Logic for NASH

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for In Vivo Nanonetwork Deployment Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Deployment Research | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|