DNA Nanostructures as Molecular Communication Networks: From Principles to Biomedical Applications

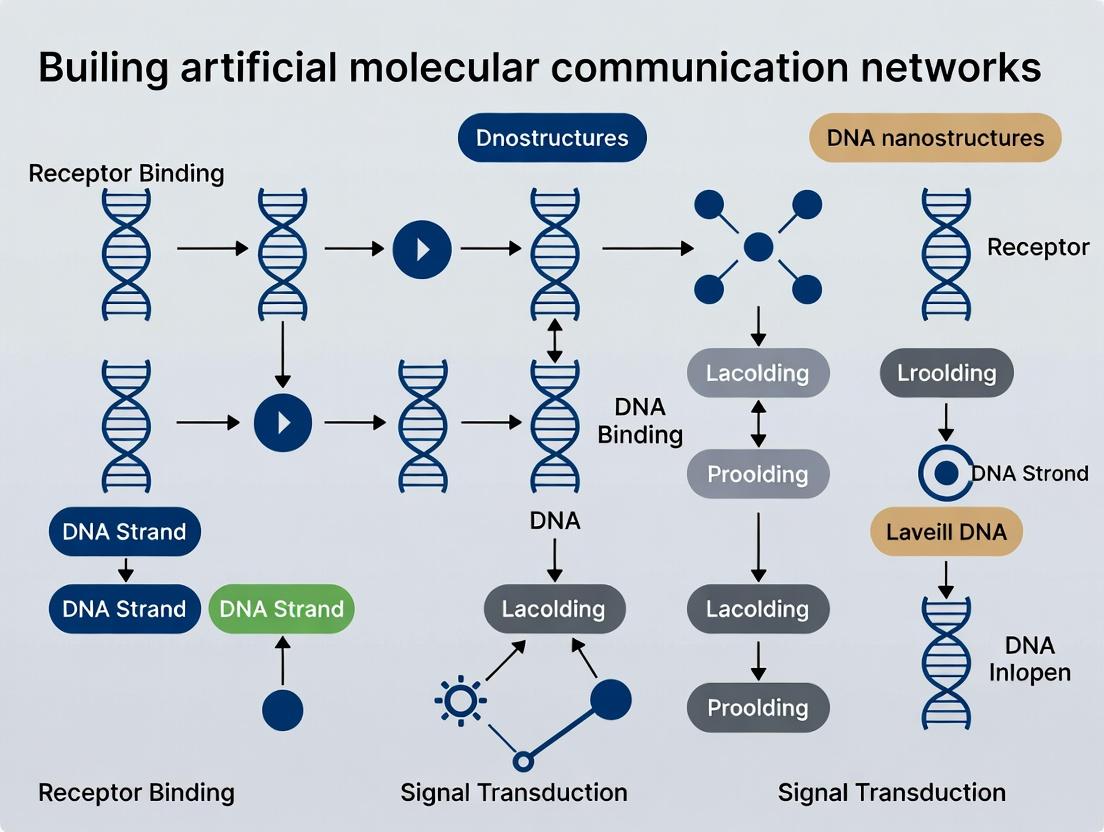

This article provides a comprehensive overview of building artificial molecular communication networks using DNA nanostructures.

DNA Nanostructures as Molecular Communication Networks: From Principles to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of building artificial molecular communication networks using DNA nanostructures. Targeted at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of DNA-based communication, details current methodological approaches for constructing sender-receiver-transmitter networks, addresses key challenges in signal fidelity and network robustness, and validates performance against traditional delivery systems. The synthesis highlights the transformative potential of these programmable networks for creating intelligent therapeutic and diagnostic platforms, offering a roadmap for future clinical translation.

The Blueprint of Life as a Circuit: Foundational Principles of DNA Communication Networks

Artificial Molecular Communication (AMC) is an emerging engineering paradigm that designs and constructs synthetic systems to encode, transmit, and receive information using molecules as carriers. Framed within the thesis on Building artificial molecular communication networks with DNA nanostructures, this field moves beyond biomimicry of natural systems (e.g., quorum sensing, neural synapses) toward precisely engineered communication protocols using programmable nanomaterials, with DNA as a primary substrate.

Foundational Principles and Quantitative Benchmarks

Table 1: Comparison of Natural and Artificial Molecular Communication Systems

| Feature | Natural Systems (e.g., Quorum Sensing) | Artificial Systems (DNA-based) |

|---|---|---|

| Information Carrier | AHL, AIP, peptides | DNA strands, RNA, proteins, nanoparticles |

| Transmission Range | ~1-10 µm (diffusion-based) | ~0.1 µm to >100 µm (engineered) |

| Data Rate | ~10^-3 - 10^-2 bits/s | ~10^-2 - 10^1 bits/s (theoretical) |

| Modulation Scheme | Concentration, pulse frequency | Sequence, concentration, structure, timing |

| Receiver Specificity | Protein receptor-ligand binding | Toehold-mediated strand displacement, aptamers |

| Key Advantage | Evolved robustness | Programmable logic, digital precision |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Recent DNA-based AMC Systems

| System Type (Year) | Channel Medium | Distance Achieved | Bit Rate/Transfer Time | Fidelity (BER/Error Rate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Strand Displacement Cascade (2023) | Microfluidic Chamber | 500 µm | ~0.016 bits/min (cascade speed) | >99% output signal |

| Liposome-based Diffusion (2022) | Agarose Gel | 1 mm | ~4.7 µm/s (diffusion speed) | ~95% reception accuracy |

| Molecule-Kicking TX/RX (2024) | Aqueous Buffer | 100 nm | 0.05 bits/s (estimated) | Experimental validation ongoing |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Basic DNA Strand Displacement Transmitter-Receiver Pair

Objective: To synthesize and validate a minimal AMC link where a "Transmitter" nanostructure releases a DNA signal strand upon a specific trigger, which is then detected by a "Receiver" structure, producing a fluorescent output.

Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Procedure:

- Transmitter Assembly:

- Prepare a 100 µL solution of the gate complex (G) at 100 nM in 1x TAE/Mg2+ buffer. Use the scaffold strand (S) and helper strands (H1, H2) listed in the toolkit.

- Anneal from 95°C to 25°C over 90 minutes using a thermal cycler.

- Purify the assembled structure using a gel filtration column (e.g., Micro Bio-Spin P-30). Verify assembly via 3% agarose gel electrophoresis (100 V, 45 min).

Receiver Assembly:

- Prepare a 100 µL solution of the reporter complex (R) at 150 nM. Combine the quencher-labeled strand (Q) and fluorophore-labeled strand (F).

- Anneal from 70°C to 25°C over 60 minutes. Purify via gel filtration.

Communication Experiment:

- In a 200 µL PCR tube, combine 50 µL of transmitter solution (final [G]=10 nM), 50 µL of receiver solution (final [R]=15 nM), and 100 µL of 1x TAE/Mg2+ buffer.

- Load tube into a real-time PCR instrument or fluorometer pre-heated to 25°C.

- Initiate measurement of fluorescence (FAM channel, Ex/Em: 492/518 nm) every 30 seconds for 30 minutes to establish baseline.

- At t=30 min, introduce the trigger strand (T) to a final concentration of 15 nM by pipette mixing. Continue fluorescence measurement for an additional 2 hours.

- Control: Run a parallel experiment without the trigger strand.

Data Analysis:

- Normalize fluorescence (F) to the initial baseline (F0) and the maximum signal from a positive control (Fmax).

- Plot (F - F0)/(Fmax - F0) vs. time. Successful communication is indicated by a sharp increase in normalized fluorescence only in the trigger-added sample post-injection.

Protocol 2: Demonstrating Diffusion-Based Molecular Signaling in a Hydrogel

Objective: To establish directional communication between two DNA-based devices separated in a 3D hydrogel matrix, simulating a tissue-like environment.

Procedure:

- Hydrogel Chamber Preparation:

- Construct a 1 mm thick, 1.5% agarose gel slab in 1x TAE/Mg2+ buffer within a custom microfluidic chamber or between two glass slides separated by a spacer.

- Using a biopsy punch or fine pipette tip, create two 2 µL wells spaced 800 µm apart.

Device Loading:

- Load the Transmitter Well with 2 µL of the pre-assembled transmitter complex (from Protocol 1, step 1) at 500 nM, pre-mixed with the specific trigger.

- Load the Receiver Well with 2 µL of the reporter complex (from Protocol 1, step 2) at 750 nM.

Signal Propagation & Imaging:

- Seal the chamber to prevent evaporation.

- Place the chamber on a confocal or epifluorescence microscope with a stage-top incubator (25°C).

- Acquire time-lapse images of the FAM channel every 5 minutes for 12 hours, focusing on the region between and including the two wells.

- Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) to quantify the mean fluorescence intensity in the receiver well over time.

Visualization of Systems and Workflows

Diagram 1: From Biological Quorum Sensing to DNA Communication

Diagram 2: Basic DNA AMC Experiment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for DNA-based AMC Experiments

| Item | Function in AMC Research | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Custom DNA Oligonucleotides | The fundamental building blocks for transmitters, receivers, and signals. | HPLC or PAGE-purified. Modified with fluorophores (FAM, Cy5) or quenchers (Iowa Black FQ). |

| Scaffold Strand (e.g., M13mp18) | Provides a long, single-stranded template for assembling complex DNA nanostructures (origami) as devices. | 7249 nucleotides; used for advanced, multi-component devices. |

| TAE/Mg2+ Buffer (1x, 12.5 mM Mg2+) | Standard assembly and reaction buffer for DNA nanostructures; Mg2+ stabilizes structure. | 40 mM Tris, 20 mM Acetic Acid, 12.5 mM Magnesium Acetate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0. |

| Thermal Cycler | For precise annealing of DNA strands to form desired nanostructures. | Ramps from 95°C to 4°C over several hours. |

| Gel Filtration Columns (e.g., Micro Bio-Spin P-30) | Purifies assembled nanostructures from excess, unbound staple strands. | Critical for reducing background noise in communication. |

| Real-Time PCR System / Fluorometer | Enables sensitive, quantitative, real-time measurement of fluorescence output from receivers. | Allows kinetic tracking of communication events. |

| Agarose (Low-Melt, High-Purity) | For creating diffusion matrices (hydrogels) to study molecular propagation in 3D. | Simulates extracellular or tissue environments. |

| Microfluidic Chambers or Glass Slides with Spacers | Provides a controlled, miniaturized environment for setting up communication channels. | Enables precise spatial separation of transmitters and receivers. |

Within the thesis framework of Building artificial molecular communication networks with DNA nanostructures, this document details the core functional units of such networks. Inspired by electromagnetic communication, molecular communication (MC) systems encode, transmit, and decode information via chemical signals. DNA nanotechnology provides an ideal substrate for engineering these components with high programmability and specificity. This note outlines the definitions, experimental data, and protocols for implementing Senders, Receivers, Transmitters, and Molecular Messages using DNA.

Core Component Definitions & Quantitative Data

Table 1: Core Components of DNA-based Molecular Communication Networks

| Component | Role in Network | Typical DNA Implementation | Key Quantitative Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Message | The information-carrying signal. | ssDNA, dsDNA, DNAzyme, Holliday junction. | Length (8-60 nt), Concentration (pM-µM), Diffusion Coefficient (~10⁻¹⁰ m²/s in water). |

| Transmitter | Encodes/Releases the Message. | DNA nanocage, liposome, gel particle, strand-displacement circuit. | Release Rate (molecules/s), Trigger Specificity (ON/OFF ratio >100:1), Latency (s-min). |

| Receiver | Detects and decodes the Message. | DNA aptamer, hairpin beacon, logic gate, CRISPR-dCas9 sensor. | Detection Limit (low fM), Sensitivity (Δ signal/Δ conc.), Response Time (min-hr). |

| Sender | The entity housing the Transmitter. | Engineered cell, vesicle, functionalized surface, macroscopic instrument. | Transmission Range (µm-mm), Power (ATP molecules/message). |

Detailed Protocols

Protocol 2.1: Fabrication of a pH-Triggered DNA Nanocage Transmitter

Objective: Construct a DNA nanocage that releases an encapsulated molecular message (a fluorescently labeled ssDNA) upon a drop in pH.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- DNA Oligonucleotides: Custom-synthesized strands for cage self-assembly (e.g., 4x 60-mer).

- Molecular Message: Cy3-labeled ssDNA (24-mer).

- Assembly Buffer: Tris-EDTA with 12.5 mM MgCl₂.

- pH Trigger Solution: Sodium citrate buffer, pH 5.0.

- Gel Filtration Column: Sephadex G-25 for purification.

Methodology:

- Cage Assembly & Loading: Mix cage strands (100 nM each) with a 5x molar excess of Message strand in assembly buffer. Heat to 95°C for 5 min, then cool from 65°C to 4°C over 2 hours.

- Purification: Pass the mixture through a gel filtration column equilibrated with assembly buffer (pH 7.6) to separate encapsulated Message from free Message. Collect the early-eluting fraction (cage complex).

- Triggered Release: Add 1 volume of pH trigger solution (pH 5.0) to 9 volumes of purified cage solution. Incubate at 25°C.

- Quantification: Monitor fluorescence de-quenching (Cy3 signal increases upon release) over 60 minutes using a plate reader. Calculate release percentage relative to a lysed cage control.

Protocol 2.2: Implementing a Toehold-Mediated Strand Displacement Receiver

Objective: Create a DNA-based receiver that produces a fluorescent output signal upon binding a specific Message strand.

Materials:

- Receiver Complex: Quencher-labeled hairpin or duplex DNA with a toehold domain.

- Input Message: Target ssDNA strand.

- Detection Buffer: PBS with 5 mM MgCl₂.

- Fluorometer or qPCR Machine.

Methodology:

- Receiver Preparation: Anneal the receiver complex (e.g., a fluorophore-quencher pair separated by a toehold-protected domain) at 1 µM in detection buffer.

- Message Introduction: Dilute receiver to 100 nM in a detection cuvette. Introduce the target Message strand at concentrations ranging from 10 nM to 1 µM.

- Signal Acquisition: Immediately monitor fluorescence (e.g., FAM, λex/em 492/517 nm) in real-time for 2 hours at 37°C.

- Data Analysis: Fit the kinetic curve to determine the strand displacement rate constant. Plot endpoint fluorescence vs. Message concentration to establish a calibration curve.

Visualization of Systems and Workflows

Title: DNA Molecular Communication Signaling Pathway

Title: pH-Triggered Message Release Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for DNA Communication Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Example Vendor/Product |

|---|---|---|

| Custom DNA Oligos | Source for constructing nanostructures, messages, and probes. | IDT, Sigma-Aldrich. |

| Fluorophore-Quencher Pairs | Enable signal transduction in reporters and receivers. | Cy3/Cy5, FAM/BHQ-1. |

| Magnesium-Containing Buffer (Mg²⁺) | Essential cation for DNA nanostructure stability and hybridization. | Tris-EDTA-Mg (TE-Mg) buffer. |

| Gel Filtration/Spin Columns | Purify assembled complexes from excess components. | Illustra MicroSpin G-25, Sephadex. |

| Fluorescence Plate Reader | Quantifies real-time signal output from receivers. | Tecan Spark, BioTek Synergy. |

| Thermal Cycler | For controlled annealing of DNA structures. | Applied Biosystems Veriti. |

| CRISPR-dCas9 Components | For engineering highly specific receiver systems in cells. | dCas9 protein, guide RNA. |

| Liposome Formulation Kit | Creates lipid-based senders/transmitters for message encapsulation. | Avanti Polar Lipids kits. |

Within the thesis framework of Building artificial molecular communication networks with DNA nanostructures, precise information encoding and signal transduction are fundamental. This document details three core strategies for engineering molecular communication: strand displacement cascades, toehold-mediated exchange, and conformational switching. These mechanisms allow for the programming of chemical reaction networks that mimic biological signaling pathways, enabling applications in biosensing, in vitro diagnostics, and controlled therapeutic delivery.

Application Note 1: Strand Displacement Cascades enable the construction of complex digital logic circuits and amplifiers at the molecular scale. A signal strand triggers a cascade of displacement reactions, propagating information through a network.

Application Note 2: Toehold-Mediated Exchange provides a universal, predictable, and programmable method for sequence-specific strand exchange. It is the foundational engine for most dynamic DNA nanotechnology, allowing for precise kinetic control.

Application Note 3: Conformational Change Switches (e.g., Holliday Junctions, tweezers) translate molecular recognition into a macroscopic shape change or movement. This is critical for creating actuators and reporters in synthetic networks.

Table 1: Kinetic and Thermodynamic Parameters for Core Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Typical Rate Constant (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Toehold Length (nt) | ΔG° (kcal/mol) | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toehold-Mediated Strand Displacement | 10⁵ - 10⁶ | 5-8 | -5 to -15 | Signal amplification, logic gating |

| Branch Migration (toehold-less) | 10⁻³ - 10² | 0 | -1 to -10 | Slow, stable state transitions |

| Holliday Junction Isomerization | 10² - 10⁴ (s⁻¹) | N/A | -2 to -5 | Binary switching, reconfigurable nanostructures |

| DNA Tweezer Opening/Closing | 10³ - 10⁵ (s⁻¹) | 5-7 | -8 to -12 | Mechanical signal transduction |

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Selected Experimental Systems

| System Type | Signal Gain | Response Time (min) | SNR Improvement | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Hairpin Assembly (CHA) | ~1000x | 60-120 | 10-50x | 2023 |

| Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) | ~5000x | 90-180 | 100x | 2022 |

| Toehold Exchange Sensor | N/A (digital) | 5-15 | >100x (vs. linear) | 2024 |

| Allosteric DNAzyme Switch | ~50x | 20-40 | 25x | 2023 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Standard Toehold-Mediated Strand Displacement Assay (Fluorescence-Based)

Purpose: To measure the kinetics and efficiency of a single strand displacement event. Reagents: See "Scientist's Toolkit" (Section 5).

- Preparation: Anneal the quenched duplex (Q-Reporter). Combine Strand A (5'-Cy3) and its complementary Quencher strand (3'-Iowa Black RQ) in 1:1.2 ratio in SELEX buffer. Heat to 95°C for 5 min, then cool slowly to 25°C at 0.1°C/s.

- Baseline Acquisition: In a black 96-well plate, mix 50 µL of 50 nM annealed Q-Reporter with 50 µL of SELEX buffer. Incubate in a fluorescence plate reader at 25°C for 5 min, measuring Cy3 fluorescence (Ex: 550 nm, Em: 570 nm) every 30s.

- Displacement Initiation: Add 20 µL of the invading Trigger Strand (pre-diluted in SELEX buffer) to achieve a final concentration of 100 nM (2:1 trigger:reporter ratio). Mix rapidly by pipetting.

- Kinetic Measurement: Immediately commence fluorescence readings every 10-15 seconds for 60-120 minutes.

- Data Analysis: Normalize fluorescence to initial (F₀) and final (Fmax, determined with excess trigger) values. Fit the normalized curve to a first-order kinetic model to obtain the observed rate constant, kobs.

Protocol 3.2: Construction and Operation of a DNA Tweezer for Conformational Signaling

Purpose: To create a mechanically reconfigurable nanostructure that reports target binding via FRET.

- Tweezer Assembly: Combine the three constituent strands (M1, M2, Linker) in equimolar ratios (500 nM each) in TM buffer (50 mM Tris, 10 mM MgCl₂, pH 8.0). Anneal from 80°C to 20°C over 60 minutes.

- FRET State Validation: Purify assembled tweezers via native PAGE (8%). Characterize the "open" state by measuring fluorescence spectra of donor (Cy3) and acceptor (Cy5) labels upon excitation of the donor. A low FRET ratio is expected.

- Trigger-Induced Closing: Incubate 100 nM purified tweezers with 120 nM Fuel Strand (complementary to both "arms") in TM buffer at 25°C. Monitor the increase in Cy5 emission (or FRET ratio) over time.

- Reset Protocol: To reopen the tweezers, add a 1.5x molar excess of Removal Strand fully complementary to the Fuel Strand. Monitor the return to low FRET.

Visualization Diagrams

Diagram Title: Toehold-Mediated Strand Displacement Mechanism

Diagram Title: Multi-Stage Signal Amplification Cascade

Diagram Title: DNA Tweezer Conformational Change Cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Specification | Example Vendor/Product |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Pure DNA Oligonucleotides | Synthesis of strands with precise sequences, often with chemical modifications (fluorescent dyes, quenchers, biotin). HPLC or PAGE purification is essential. | Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), Eurofins Genomics |

| Fluorophore-Quencher Pairs | For real-time reporting of strand displacement. Common pairs: FAM/BHQ-1, Cy3/Iowa Black RQ, Cy5/BHQ-2. | LGC Biosearch Technologies, ATDBio |

| High-Fidelity Thermostable Polymerase | For enzymatic amplification steps in coupled assays or circuit generation. | Q5 Hot-Start (NEB), Phusion (Thermo) |

| Magnetic Beads (Streptavidin) | For purification of biotinylated complexes and removal of excess strands. | Dynabeads (Thermo), MagneSphere (Promega) |

| Structure-Stabilizing Cations | MgCl₂ is critical for stabilizing duplex DNA and complex nanostructures. Typical concentration: 5-20 mM. | Molecular biology grade, Sigma-Aldrich |

| Nuclease-Free Buffers | SELEX buffer or TM Buffer (Tris, Mg2+) provides a consistent, nuclease-free environment for reactions. | Made in-lab with DEPC-treated water and filtered, or commercial (Thermo) |

| Native PAGE Gels (6-12%) | For analyzing assembly yields and purifying multi-strand complexes. | Self-cast or commercial pre-cast gels (Bio-Rad, Novex) |

| Fluorescence Plate Reader | For high-throughput kinetic measurements of fluorophore-labeled reactions. | SpectraMax (Molecular Devices), CLARIOstar (BMG Labtech) |

The Role of DNA Origami and Self-Assembled Nanostructures as Network Scaffolds and Hubs

Within the broader thesis on "Building artificial molecular communication networks with DNA nanostructures," this document details the application of DNA origami and self-assembled nanostructures as precise scaffolds and functional hubs. These structures enable the spatial organization of molecular components, facilitating controlled interaction pathways essential for synthetic biological networks, biosensing, and targeted therapeutic delivery.

Application Notes

Scaffolding for Molecular Network Assembly

DNA origami provides a programmable "breadboard" for arranging network components like proteins, nanoparticles, and nucleic acids with nanometer precision. This spatial control is critical for constructing artificial signaling cascades or metabolic pathways where reaction efficiency depends on the precise relative positioning of enzymes and cofactors.

Functional Hubs for Signal Integration and Routing

Self-assembled DNA nanostructures can act as hubs that receive multiple molecular inputs, process them via strand displacement reactions, and produce defined outputs. This transforms passive scaffolds into active, decision-making nodes within a communication network, mimicking logic gates in synthetic biology.

In Vivo & Drug Delivery Applications

Structures like DNA tetrahedra and tubes are used as biocompatible carriers. As network hubs, they can be functionalized with targeting ligands, therapeutic cargos (e.g., siRNA, drugs), and reporter molecules, enabling coordinated delivery and activation at disease sites.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Select DNA Nanostructure Scaffolds & Hubs

| Structure Type | Typical Size (nm) | Addressable Sites | Ligand Binding Efficiency | Key Demonstrated Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flat Rectangular Origami | 70 x 100 | ~200 | 60-95% | Protein array for enzyme cascade |

| 6-helix Bundle (6HB) Tube | 10 x 50 | ~30 | >90% | Intracellular siRNA delivery vehicle |

| DNA Tetrahedron | Edge: ~10 | 4 (vertices) | ~80% | Targeted antigen presentation |

| Multi-arm Junction Hub | Core: ~5 | 3-8 (arms) | 85-98% | Logic gate (AND, OR) for molecular computation |

| Origami Nanorobot | 45 x 35 x 35 | Multiple | N/A | Targeted thrombin delivery (payload release) |

Table 2: Recent Experimental Outcomes in Network Applications

| Application | Signal Amplification Factor | Response Time | Specificity/On-off Ratio | Reference System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffolded Enzyme Cascade | 4.8x over free solution | ~300 s | N/A | Glucose Oxidase/HRP on origami |

| miRNA-Triggered Logic Gate | N/A | 1-2 hours | >10:1 | YES/AND gate for cell classification |

| siRNA Delivery (in vitro) | N/A (Gene Knockdown) | 24-48 h | 70-90% knockdown | Tetrahedron targeting cancer cells |

| Protein Detection via Nanoarray | Detection limit: 10 pM | < 30 min | Distinguishes homologs (>5:1) | Antibody array on origami |

Detailed Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a Rectangular DNA Origami Scaffold

Objective: To create a staple-addressable 2D scaffold for organizing network components.

Materials:

- M13mp18 phage genomic DNA (7249 bases, 50 nM).

- Staple strands (unmodified, 5'-thiolated, or biotinylated for conjugation) in 200x molar excess (10 µM each in DNase-free water).

- Folding Buffer: 20 mM Tris, 2 mM EDTA, 12.5 mM MgCl₂, pH 8.0.

- Thermal cycler.

- Agarose gel (2%), TBE-Mg buffer (0.5x TBE, 11 mM MgCl₂).

- Purification: 100 kDa molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) centrifugal filters.

Procedure:

- Mix: Combine M13 scaffold (10 µL, 5 nM final), staple strand mix (10 µL, 100 nM each final), and folding buffer (80 µL) for a 100 µL reaction.

- Thermal Annealing: Program thermal cycler: 80°C for 5 min; then cool from 65°C to 25°C over 14 hours (3°C/hour decrements).

- Purification: Concentrate the reaction mixture using a 100 kDa MWCO filter (centrifuge at 10,000 x g, 4°C, 10 min). Wash twice with 200 µL folding buffer to remove excess staples.

- Quality Control: Analyze 5 µL of purified product on a 2% agarose gel (0.5x TBE + 11 mM MgCl₂) at 70 V for 90 min. Stain with SYBR Safe. A single, sharp, high-molecular-weight band indicates successful folding.

Protocol: Functionalization of a DNA Origami with Network Components

Objective: To site-specifically conjugate proteins and oligonucleotides to the scaffold.

Materials:

- Purified DNA origami (from Protocol 4.1).

- Maleimide-activated protein or thiolated oligonucleotide.

- Conjugation Buffer: Folding buffer + 1 mM TCEP (freshly added).

- Size-exclusion spin columns (e.g., Illustra MicroSpin G-50).

Procedure:

- Activation: For thiolated staples on the origami, incubate the purified origami with 1 mM TCEP in conjugation buffer for 1 hour at room temperature to reduce disulfide bonds.

- Conjugation: Add a 5-10x molar excess (relative to binding sites) of maleimide-activated protein or thiolated oligonucleotide. Incubate at 25°C for 12-16 hours.

- Purification: Pass the mixture through a G-50 size-exclusion spin column pre-equilibrated with folding buffer to remove unconjugated components.

- Verification: Use Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) or transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to visualize successful localization of components (often via gold nanoparticle tags on oligonucleotides).

Protocol: Assembling a Multi-Hub DNA Network for Signal Processing

Objective: To construct a YES/AND logic gate using multi-arm junction hubs.

Materials:

- DNA strand components: Input strands (I1, I2), fuel strands, output reporter strand with fluorophore/quencher pair.

- Pre-assembled 3-arm junction hubs (H1, H2) with specific toehold domains.

- Reaction Buffer: 1x PBS, 12.5 mM MgCl₂.

- Fluorescence plate reader or real-time PCR machine.

Procedure:

- Network Assembly: Mix hubs H1 and H2 (5 nM each) in reaction buffer. Anneal from 37°C to 25°C over 1 hour.

- Logic Operation: Aliquot the network mixture into three tubes.

- Tube 1 (Control): Add buffer only.

- Tube 2 (YES Gate): Add input I1 (10 nM).

- Tube 3 (AND Gate): Add both inputs I1 and I2 (10 nM each).

- Detection: Add the output reporter strand (10 nM) to all tubes. Immediately transfer to a fluorescence-compatible plate.

- Measurement: Monitor fluorescence (e.g., FAM, Ex/Em: 495/520 nm) every 30 seconds for 2 hours at 25°C. A significant increase in fluorescence only in the presence of the correct input(s) indicates successful logic operation.

Visualization: Diagrams & Workflows

Diagram 1: DNA Origami Scaffold Fabrication Workflow

Diagram 2: DNA Hub Acting as an AND Logic Gate

Diagram 3: Targeted Delivery by a Functionalized DNA Nanostructure Hub

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for DNA Nanostructure Network Research

| Item | Function & Key Feature | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| M13mp18 Scaffold | Long, single-stranded DNA template for origami folding. Provides the structural backbone. | M13mp18 ssDNA (Bayou Biolabs, cat# P-107) |

| Phosphoramidites | For synthesizing staple strands and functional oligonucleotides (biotin, thiol, dyes). | Standard & Modified Phosphoramidites (Glen Research) |

| Magnesium Buffer | Critical cation for stabilizing DNA origami structure. High-purity MgCl₂ is essential. | Molecular Biology Grade MgCl₂ (Sigma-Aldrich, cat# M1028) |

| Thermal Cycler | For precise control of the slow annealing ramp required for nanostructure self-assembly. | Any programmable cycler with a slow ramp function. |

| 100 kDa MWCO Filters | For purifying folded origami from excess staple strands via size exclusion. | Amicon Ultra 0.5 mL Centrifugal Filters (Merck, cat# UFC510096) |

| TCEP-HCl | Reducing agent for activating thiol-modified DNA for conjugation to maleimide-proteins. | Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine HCl (Thermo, cat# 20490) |

| Maleimide Activator | For creating thiol-reactive proteins for site-specific conjugation to DNA scaffolds. | SM(PEG)₂ Crosslinkers (Thermo Scientific) |

| SYBR Safe Stain | Low-toxicity gel stain for visualizing DNA nanostructures via agarose gel electrophoresis. | SYBR Safe DNA Gel Stain (Invitrogen, cat# S33102) |

Application Notes

This document details the application of DNA nanostructures as superior materials for constructing artificial molecular communication networks, leveraging their innate advantages over traditional synthetic polymers. These networks are foundational for developing advanced biosensing, diagnostic, and therapeutic delivery systems.

Programmability

The predictable base-pairing of DNA allows for the precise design of nanostructures with atomic-scale accuracy. This enables the engineering of complex reaction networks, logic gates, and spatially organized components that are not feasible with stochastic synthetic polymers.

Biocompatibility

DNA is a naturally occurring, biodegradable polymer with low inherent toxicity. DNA nanostructures exhibit excellent serum stability when properly designed and modified, and they degrade into nucleotides, minimizing long-term accumulation risks compared to many non-degradable synthetic polymers (e.g., polystyrene, polyacrylates).

Signal Specificity

Watson-Crick hybridization provides an extremely high-fidelity recognition mechanism. This allows for the design of communication pathways where signals are transmitted only between perfectly complementary components, drastically reducing crosstalk and false-positive signals common in systems reliant on less specific interactions (e.g., hydrophobic or charge-based).

Table 1: Comparative Properties of DNA Nanostructures vs. Synthetic Polymers

| Property | DNA Nanostructures (Holliday Junction-based) | Typical Synthetic Polymer (PEG-based) | Measurement Method / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programmability (Structural Precision) | Exact number of branches, angles, and functional sites | Polydisperse; random coil or micellar structures | Cryo-EM, Gel Electrophoresis |

| Biodegradation Half-life (in serum) | 4 - 48 hours (depends on modification) | Non-degradable or days to months | Fluorescence quenching assay |

| Binding Affinity (Kd for target) | ~1 nM - 10 pM (sequence-dependent) | ~1 µM - 100 nM (ligand-dependent) | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Logic Gate | >50:1 | Typically <10:1 | Fluorescence output measurement |

| Cellular Uptake Efficiency (in HeLa cells) | Up to 80% with targeting | 1-15% (passive) | Flow Cytometry |

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for DNA Communication Networks

| Network Function | DNA-Based System Performance | Key Advantage Demonstrated | Reference (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cascade Amplification | 10^6-fold signal amplification in 2 hours | Programmability & Specificity | J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2023 |

| Multi-Input Logic Gate (AND) | Off/On ratio > 100:1 | Specificity & Programmability | Nat. Nanotechnol., 2022 |

| Cell-Cell Communication Mimicry | Message transmission fidelity >99% | Specificity | Sci. Adv., 2024 |

| In Vivo Tumor Targeting | 8x higher accumulation than passive polymer | Biocompatibility & Programmability | ACS Nano, 2023 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assembly and Purification of a DNA Tetrahedron for Molecular Messaging

Objective: To construct a stable, monodisperse DNA nanostructure for use as a communication node or carrier.

Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Method:

- Oligonucleotide Preparation: Resequence-purified DNA strands (S1-S4) in 1x TE Buffer (pH 8.0) to 100 µM. Combine equimolar ratios (e.g., 10 µL of each 100 µM strand) in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Annealing: Add 60 µL of nuclease-free water and 100 µL of 5x Folding Buffer (500 mM Tris, 100 mM MgCl2, pH 8.0) to the strand mixture (total volume 200 µL). Mix gently.

- Thermal Ramp: Place the tube in a thermal cycler. Use the program: 95°C for 5 min, then rapid cool to 4°C over 1 min, then slow ramp from 65°C to 4°C over 90 minutes.

- Purification (Spin Column): Transfer the annealed product to a 100 kDa molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) centrifugal filter. Centrifuge at 10,000 x g for 8 minutes at 4°C. Discard flow-through.

- Wash: Add 400 µL of 1x TAE/Mg2+ Buffer (40 mM Tris, 20 mM Acetic acid, 2 mM EDTA, 12.5 mM MgCl2, pH 8.0) to the filter. Centrifuge again at 10,000 x g for 8 minutes. Repeat wash once.

- Recovery: Invert the filter into a clean collection tube. Centrifuge at 2,000 x g for 2 minutes to recover the purified tetrahedron (~40 µL).

- Validation: Analyze 5 µL of the product via 3% agarose gel electrophoresis (run in 1x TAE/Mg2+ buffer at 70V for 60 min, stain with SYBR Gold). A single, sharp band at the expected mobility confirms successful assembly.

Protocol 2: Demonstrating Signal Specificity in a DNA Strand Displacement Cascade

Objective: To visualize the high-fidelity transmission of a molecular signal through a programmed cascade, highlighting minimal leakage.

Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit."

Method:

- Prepare Reporter Complex: Mix Strand A (quencher-labeled) and Strand B (fluorophore-labeled) at a 1:1.2 ratio in 1x TAE/Mg2+ Buffer. Heat to 90°C for 2 min and cool slowly to room temperature to form a double-stranded complex with quenched fluorescence.

- Set Up Reaction Tubes:

- Tube 1 (Specific Signal): 50 nM Reporter Complex + 50 nM Initiator I (fully complementary to cascade input).

- Tube 2 (Non-Specific Control): 50 nM Reporter Complex + 50 nM Initiator NS (single-base mismatch to cascade input).

- Tube 3 (Background): 50 nM Reporter Complex only.

- Initiate Cascade: To Tubes 1 and 2, add 50 nM of pre-assembled DNA gate solution. Do not add to Tube 3.

- Kinetic Measurement: Immediately transfer each mixture to a quartz cuvette or a plate reader. Measure fluorescence (Ex: 490 nm, Em: 520 nm) every 30 seconds for 3 hours at 25°C.

- Analysis: Plot fluorescence vs. time. A sharp increase only in Tube 1 demonstrates signal specificity. Calculate the final signal-to-noise ratio as (FTube1 - FTube3) / (FTube2 - FTube3).

Visualizations

Diagram 1: DNA Strand Displacement Signaling Cascade

Diagram 2: Artificial Molecular Communication Network

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Protocol | Example Product/Catalog # | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Purified DNA Oligos | Building blocks for nanostructures and circuits. | IDT Ultramers, Sigma Genosys | HPLC or PAGE purification is essential. |

| Thermal Cycler | For controlled annealing of DNA structures. | Bio-Rad T100, Eppendorf Mastercycler | Must allow slow ramp rates (<1°C/min). |

| 100 kDa MWCO Centrifugal Filters | Size-exclusion purification of nanostructures. | Amicon Ultra-0.5 mL, Millipore UFC510024 | Pre-wet with buffer to maximize recovery. |

| TAE/Mg2+ Buffer (10x Stock) | Provides ionic strength and Mg2+ for DNA folding. | 400 mM Tris, 200 mM Acetate, 20 mM EDTA, 125 mM MgCl2, pH 8.0 | Filter sterilize (0.22 µm) and store at 4°C. |

| SYBR Gold Nucleic Acid Gel Stain | High-sensitivity visualization of DNA in gels. | Invitrogen S11494 | Use at 1:10,000 dilution in 1x TAE buffer. |

| Fluorophore/Quencher Labeled Oligos | For constructing signal reporters. | Cy3/BHQ-2, FAM/Iowa Black FQ labeled strands | Store aliquoted in dark at -20°C. |

| Fluorescence Spectrophotometer/Plate Reader | Kinetic measurement of strand displacement. | Agilent Cary Eclipse, BioTek Synergy H1 | Ensure stable temperature control. |

Building the Network: Methodologies and Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedicine

Application Notes

This document outlines the design and assembly principles for creating robust DNA nanostructures that function as communication nodes within artificial molecular networks. These nodes are fundamental components for a broader thesis on Building artificial molecular communication networks with DNA nanostructures, aiming to create programmable systems for sensing, computation, and targeted therapeutic delivery.

Effective communication nodes require precise spatial addressability, dynamic reconfigurability, and chemical/biochemical stability. The following protocols are optimized for creating nodes based on multi-arm DNA junctions and tile-based structures (e.g., DX tiles, Holliday junctions) that can transmit signals via strand displacement cascades, ligand binding, or enzyme activity.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Design andIn SilicoModeling of a 4-Arm Communication Node

Objective: To create a stable, four-arm DNA junction with orthogonal sticky ends for downstream node networking.

Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table. Software Requirements: caDNAno, CanDo, NUPACK, or oxDNA for simulation.

Procedure:

- Scaffold Routing: Using caDNAno, select a scaffold (e.g., M13mp18, 7249 nt). Route the scaffold through four distinct double-helical arms arranged in a cruciform shape. Ensure crossover points are spaced at intervals consistent with the helical pitch (typically every 16-32 bases for DX tiles).

- Staple Design: Generate staple strands that hybridize to the scaffold, forming the double-stranded arms. Terminate each arm with a unique, single-stranded overhang (sticky end, 5-7 nt) for specific inter-node linkage.

- Stability Check: Use NUPACK to analyze secondary structure formation of individual staples and junction complexes at 25°C, 10 mM Mg2+ conditions. Adjust sequences to minimize off-target hybridization.

- Structural Validation: Perform coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulation using oxDNA to predict the 3D structure and flexibility of the junction. Confirm the arms maintain intended angles and rigidity.

Protocol 2: Stepwise Thermal Annealing for Node Assembly

Objective: To physically assemble monodisperse DNA nanostructure nodes from stoichiometric mixtures of oligonucleotides.

Procedure:

- Staple Preparation: Combine all staple strands (including linker strands with fluorescent or chemical modifications if required) in nuclease-free water to a final concentration of 100 µM each. Pool staples to a final working concentration of 1 µM each.

- Master Mix Assembly: In a thin-walled PCR tube, mix:

- Scaffold strand (M13mp18): 10 nM final concentration

- Pooled staple strands: 100 nM final concentration each

- Folding Buffer (1x TAE with 12.5 mM MgCl2): To final volume

- Thermal Annealing: Place the tube in a thermal cycler and run the following program:

- Step 1: Heat to 65°C for 10 minutes (denaturation).

- Step 2: Cool from 65°C to 45°C at a rate of 1°C per 5 minutes (slow annealing for nucleation).

- Step 3: Cool from 45°C to 35°C at a rate of 1°C per 15 minutes (precise structural folding).

- Step 4: Cool from 35°C to 20°C at a rate of 1°C per minute (final stabilization).

- Step 5: Hold at 4°C.

- Purification: Purify the assembled structures using agarose gel electrophoresis (2% agarose, 0.5x TBE, 11 mM MgCl2, 4°C run) or ultrafiltration (100 kDa MWCO) to remove excess staples. Visualize with SYBR Gold stain.

Protocol 3: Validation via Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

Objective: To confirm the structural integrity and morphology of assembled nodes.

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Cleave a freshly peeled mica disc (1 cm diameter). Deposit 20 µL of 10 mM NiCl2 solution for 2 minutes, then rinse with ultrapure water and dry under nitrogen.

- Sample Deposition: Dilute purified node sample to ~0.5 nM in 1x folding buffer. Apply 10 µL to the treated mica surface. Incubate for 2 minutes.

- Washing: Rinse the mica disc gently with 2 mL of ultrapure water to remove salts. Dry under a stream of nitrogen.

- Imaging: Perform tapping-mode AFM in air using a silicon cantilever. Scan a 2 µm x 2 µm area to locate nodes, then high-resolution scan a 500 nm x 500 nm area to visualize individual structures. Analyze arm lengths and junction integrity.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Node Assembly Robustness

| Metric | Target Value | Measurement Technique | Significance for Communication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assembly Yield | >70% | Densitometry analysis of agarose gel bands | Determines functional node concentration in network. |

| Structural Purity | >80% homogeneous | AFM particle counting (>100 particles) | Ensures consistent signal transmission pathways. |

| Tm of Sticky Ends | 25-40°C | UV Melting Curve (260 nm) | Predicts stable inter-node linking at working temperature. |

| Mg2+ Stability Range | 5-20 mM | Agarose gel mobility shift assay | Informs buffer compatibility for downstream applications. |

| Toehold Kinetics (k₁) | 10⁵ - 10⁶ M⁻¹s⁻¹ | Fluorescence kinetics (FRET/quenching) | Dictates maximum signal propagation speed in network. |

Visualization

Title: DNA Node Assembly and Validation Workflow

Title: Strand Displacement Signaling Pathway in a DNA Node

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Node Assembly

| Item | Function & Critical Parameters |

|---|---|

| Scaffold DNA (e.g., M13mp18) | Long, single-stranded DNA providing structural backbone. Purity and homogeneity are critical for yield. |

| Phosphoramidite-synthesized Staples | Chemically synthesized oligonucleotides (40-60 nt) that fold the scaffold. Require HPLC purification for high yield. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Ligase (e.g., T4 Ligase) | For sealing nicks in structures or permanently ligating sticky ends to form networks. Mg2+ dependent. |

| TAE/Mg2+ Folding Buffer | Standard buffer (Tris-Acetate-EDTA) with 10-20 mM MgCl2. Mg2+ neutralizes phosphate repulsion for stability. |

| Ultrafiltration Concentrator (100 kDa MWCO) | For buffer exchange and removal of excess staples/salts post-assembly. Maintains node integrity. |

| SYBR Gold Nucleic Acid Gel Stain | High-sensitivity, UV-excitable dye for visualizing nanostructures in agarose gels. |

| Nickel-coated Mica Disc | Substrate for AFM sample preparation. Ni2+ cations electrostatically bind DNA for stable imaging. |

| Fluorophore/Quencher-modified Oligos | Strands labeled with dyes (e.g., Cy3/Cy5) or quenchers (e.g., Iowa Black) for functional signal readout. |

Application Notes and Protocols

Within the thesis framework of Building artificial molecular communication networks with DNA nanostructures, this document outlines core signal propagation methodologies. These techniques enable the construction of complex, programmable, and autonomous molecular circuits that process information and perform computations at the nanoscale, with direct applications in biosensing and smart therapeutic delivery.

1. Signal Propagation via DNA Strand Displacement Cascades

DNA strand displacement (DSD) is the fundamental mechanism for propagating signals in artificial molecular networks. A single-stranded "invader" displaces a pre-hybridized "incumbent" strand from a duplex, releasing an output strand that can serve as the input for the next node in a cascade.

- Protocol: Three-Stage DSD Cascade

- Objective: To demonstrate unidirectional signal propagation through sequential strand displacement events.

- Materials: Purified DNA oligonucleotides (see Reagent Solutions Table 1), TM buffer (20 mM Tris, 12.5 mM MgCl2, pH 8.0), thermal cycler or heat block, fluorescence spectrophotometer.

- Procedure:

- Gate Preparation: For each of the three cascade stages (S1→S2, S2→S3, S3→Output), pre-anneal the gate complex. Mix the two complementary strands of each gate at 1 µM concentration each in TM buffer. Heat to 95°C for 5 minutes and cool slowly to 25°C over 90 minutes.

- Cascade Assembly: Combine the three pre-formed gate complexes (S1-Gate, S2-Gate, S3-Gate) at a final concentration of 100 nM each in TM buffer in a single reaction tube. Incubate at 25°C for 5 minutes.

- Signal Initiation: Introduce the initiator strand (I1) at a final concentration of 120 nM to the reaction mix. Vortex gently and incubate at 25°C.

- Kinetic Monitoring: Transfer the reaction to a fluorescence cuvette. If strands are labeled with fluorophore/quencher pairs (e.g., FAM/BHQ1), monitor fluorescence (ex: 492 nm, em: 518 nm) every 30 seconds for 2-4 hours. The observed sigmoidal fluorescence increase indicates successful cascading propagation.

Table 1: Representative Kinetics Data for a Three-Stage DSD Cascade (25°C, 100 nM gates)

| Stage Transition | Time to 50% Completion (t₁/₂) | Effective Rate Constant (k, M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Amplification Gain per Stage* |

|---|---|---|---|

| I1 → S2 | 15 ± 3 min | ~10³ | 1.0 (Reference) |

| S2 → S3 | 45 ± 7 min | ~3 x 10² | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| S3 → F (Output) | 70 ± 10 min | ~1 x 10² | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

*Amplification gain defined as moles of output per mole of input for that stage.

2. Catalytic Networks: Hairpin Assembly Cascades

Catalytic networks, such as the Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) and Catalytic Hairpin Assembly (CHA), provide nonlinear signal amplification. A single catalyst strand triggers the self-assembly of multiple DNA hairpins, generating a long nicked duplex or numerous displaced strands.

- Protocol: Catalytic Hairpin Assembly (CHA) Circuit

- Objective: To detect a specific DNA catalyst strand with high sensitivity via isothermal, enzyme-free amplification.

- Materials: DNA hairpins H1 and H2 (see Reagent Solutions), catalyst strand (target), reporter complex (duplex with fluorophore-quencher pair), TM buffer.

- Procedure:

- Hairpin Preparation: Individually anneal hairpins H1 and H2 (1 µM in TM buffer) by heating to 95°C for 2 minutes and cooling to 25°C over 60 minutes to ensure proper folding.

- Reporter Complex Preparation: Anneal fluorophore-labeled strand F and quencher-labeled strand Q (1 µM each) similarly to form the reporter duplex (F:Q).

- Reaction Setup: In a reaction tube, mix H1 and H2 (final 50 nM each) and the F:Q reporter (final 100 nM) in TM buffer.

- Target Addition & Detection: Add the target catalyst strand across a dilution series (e.g., 0, 1, 5, 10, 50 nM). Incubate at 37°C for 60-90 minutes.

- Signal Readout: Measure fluorescence. The catalyst opens H1, which then opens H2, releasing a strand complementary to F:Q. This displaces F from Q, generating a fluorescent signal proportional to the initial target concentration.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of a Model CHA Amplification Circuit

| Parameter | Value / Result |

|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 50 pM (in buffer) |

| Dynamic Range | 3 orders of magnitude (0.05 nM - 50 nM) |

| Amplification Factor | ~200-fold (vs. direct hybridization) |

| Reaction Time to Saturation | 80 minutes at 37°C |

| Single-Base Mismatch Discrimination | >10-fold signal reduction |

3. Amplification Circuits: DNAzyme Cascades

DNAzymes are catalytic DNA sequences that can perform reactions like cleavage of a chimeric RNA-DNA substrate. Cascading DNAzyme circuits allow for robust chemical amplification.

- Protocol: Two-Stage DNAzyme Cascade with Fluorescent Readout

- Objective: To cascade two DNAzyme reactions, where the product of the first DNAzyme activates the second.

- Materials: Substrate 1 (RNA-DNA chimeric, labeled with fluorophore/quencher), DNAzyme 1 (inactive, blocked by a protecting strand), DNAzyme 2 (inactive, requires a specific activator strand), cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5).

- Procedure:

- Stage 1 Setup: Combine inactive DNAzyme 1 complex (50 nM) with Substrate 1 (200 nM) in cleavage buffer.

- Initiation: Add the external trigger (e.g., a specific oligonucleotide) at 10 nM to activate DNAzyme 1.

- Cascade: DNAzyme 1 cleaves Substrate 1, releasing an oligonucleotide product that serves as the activator for DNAzyme 2. DNAzyme 2 is pre-present in the reaction mix with its own substrate (Substrate 2, 200 nM).

- Readout: Monitor fluorescence from the cleavage of both Substrate 1 and Substrate 2 at their respective wavelengths. The kinetic trace will show a lag phase followed by a steeper increase, indicating signal amplification through the second DNAzyme stage.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for DNA-Based Signal Propagation Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Ultrapure DNA Oligonucleotides | Synthetic, HPLC-purified strands form the basis of all gates, substrates, and fuels. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (FAM, Cy3, Cy5) & Quenchers (BHQ, Dabcyl) | Enable real-time, non-destructive monitoring of strand displacement and cleavage events. |

| High-Purity MgCl2 Solution | Divalent magnesium ions are critical for stabilizing DNA duplexes and DNAzyme activity. |

| Thermocycler with Thermal Ramp | For precise and reproducible annealing of DNA hairpins and multi-strand complexes. |

| Fluorescence Plate Reader or Spectrophotometer | For high-throughput or cuvette-based kinetic measurements of reaction progress. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Kits (e.g., NAP-5/10 columns) | For rapid buffer exchange or removal of excess fluorophores/unincorporated strands. |

Visualization of Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: Three-stage DNA strand displacement cascade workflow.

Diagram 2: Catalytic hairpin assembly (CHA) mechanism.

Diagram 3: Two-stage DNAzyme cascade with signal amplification.

This Application Notes document provides detailed experimental protocols and analysis for the development of conditional, logic-gated drug delivery systems, situated within a broader thesis on Building artificial molecular communication networks with DNA nanostructures. The aim is to enable researchers to implement and adapt these advanced therapeutic strategies.

Smart drug delivery systems utilize molecular computation to process environmental cues and execute controlled therapeutic actions. The following tables summarize key performance metrics from recent seminal studies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Logic-Gated DNA Nanostructures for Cancer Cell Targeting

| System Architecture | Target Cell / Condition | Payload | Release Logic | Efficacy (vs. Control) | Key Reference (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Origami Cuboid | MUCI+ & EpCAM+ Cells | Doxorubicin | AND (Protein A AND Protein B) | 5x increased cytotoxicity in dual-positive cells | (Douglas et al., 2012) |

| DNA Tetrahedron | MicroRNA-21 & miRNA-122 | siRNA | AND (miR-21 AND miR-122) | >80% target gene knockdown only with both inputs | (Li et al., 2018) |

| Aptamer-Gated Nano-Device | ATP (High intracellular) | Doxorubicin | AND (Aptamer Lock AND ATP Key) | ~70% tumor growth inhibition in vivo | (Wu et al., 2020) |

| Hybrid DNA/Protein Logic | MMP-2 & MMP-7 | Monomethyl auristatin E | OR (MMP-2 OR MMP-7) | Significant tumor reduction in 4T1 xenografts | (Li et al., 2021) |

Table 2: Characterization Data for Logic-Gated Nanocarriers

| Parameter | Typical Measurement Technique | Representative Value Range | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrodynamic Diameter | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | 20 - 200 nm | Impacts circulation time and tumor accumulation (EPR effect). |

| Zeta Potential | Electrophoretic Light Scattering | -10 mV to -30 mV | Influences colloidal stability and cellular interaction. |

| Payload Encapsulation Efficiency | HPLC / Fluorescence Spectroscopy | 60% - 95% | Determines drug loading capacity and cost-effectiveness. |

| Serum Stability (Half-life) | Gel Electrophoresis / DLS over time | 6 - 48 hours | Critical for in vivo application and delivery window. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 2.1: Assembly of an AND-Gated DNA Tetrahedron for Dual-miRNA Sensing

This protocol details the construction of a tetrahedral DNA nanostructure that releases a therapeutic siRNA only in the presence of two specific tumor-associated microRNAs.

Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" below. Procedure:

- Strand Hybridization: Combine the four specifically designed oligonucleotide strands (S1, S2, S3, S4) at 1 µM each in 1x TM Buffer (20 mM Tris, 50 mM MgCl₂, pH 8.0). Use nuclease-free water.

- Annealing: Heat the mixture to 95°C for 5 minutes in a thermal cycler, then rapidly cool to 4°C at a rate of 1°C per minute.

- Purification: Purify the assembled tetrahedron using gel electrophoresis (10% native PAGE, 100 V, 90 min in 1x TBE + 11 mM MgCl₂). Excise the band corresponding to the correct structure and elute using a commercial gel extraction kit.

- Functionalization: Conjugate the therapeutic siRNA to the tetrahedron's interior via a complementary linker strand during the initial assembly (Step 1). The siRNA is caged by two "lock" strands complementary to target miRNA-21 and miRNA-122.

- Validation: Confirm assembly and size via Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) imaging in tapping mode and DLS.

Protocol 2.2: In Vitro Validation of Logic-Gated Cytotoxicity

Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Culture target cells (e.g., HeLa, high in miR-21 and miR-122) and control cells (e.g., HEK293, low in both) in appropriate media.

- Transfection/Treatment: Seed cells in a 96-well plate. At 70% confluency, treat with:

- Group A: AND-gated tetrahedron (100 nM in siRNA).

- Group B: Scrambled-control nanostructure.

- Group C: Free siRNA.

- Group D: Buffer only.

- Incubation: Incubate for 48-72 hours.

- Viability Assay: Perform an MTT or CellTiter-Glo assay. Measure absorbance/luminescence.

- Logic Verification: For treated cells, extract total RNA and quantify target gene knockdown via qRT-PCR to confirm AND-gate activation.

Visualization: Pathways and Workflows

Title: AND-Gate miRNA Sensing Pathway for siRNA Release

Title: Logic-Gated Therapeutic Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function in Protocols | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Custom DNA Oligonucleotides (ssDNA) | Building blocks for nanostructure assembly. | HPLC or PAGE purification required; stability in design for toehold regions. |

| Therapeutic Cargo (siRNA, Doxorubicin) | Active payload for delivery. | Must be compatible with conjugation or encapsulation chemistry (e.g., intercalation for Dox). |

| Nuclease-free Buffers (TM Buffer, TAE/Mg²⁺) | Maintain DNA structural integrity and facilitate hybridization. | MgCl₂ concentration is critical for folding DNA origami and tetrahedra. |

| Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) Kit | Purification and validation of assembled nanostructures. | Gels must be run with Mg²⁺ in buffer to prevent denaturation. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument | Measures hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity. | Sample must be free of large aggregates; low concentration ideal. |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Setup | Visualizes nanostructure morphology and assembly yield. | Mica surface functionalization (e.g., with APTES) may be needed for imaging. |

| Cell Viability Assay Kit (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo) | Quantifies cytotoxicity and logic-gated therapeutic effect. | Choose assay compatible with your cargo (e.g., fluorescent drugs can interfere). |

Thesis Context: This work is a component of a broader thesis on Building artificial molecular communication networks with DNA nanostructures, focusing on the implementation of DNA-based circuits as programmable, autonomous diagnostic systems within live cells.

Artificial DNA networks are engineered to mimic natural signal transduction pathways. They function as intracellular biosensors by detecting specific molecular triggers (e.g., mRNA, proteins, small molecules) and producing a quantifiable output, typically fluorescent signals or therapeutic actuators. Their programmability via Watson-Crick base pairing allows for precise logic-gated operations (AND, OR, NOT) within the complex cellular milieu.

Application Notes

Key Target Biomarkers & Applications

Table 1: Intracellular Targets for DNA Network Biosensors

| Target Class | Example Biomarker | Associated Disease/Condition | Typical DNA Network Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Messenger RNA (mRNA) | TK1 mRNA, Survivin mRNA | Various cancers (proliferation markers) | Catalytic hairpin assembly (CHA), hybridization chain reaction (HCR) |

| MicroRNA (miRNA) | miR-21, miR-155 | Oncogenesis, tumor progression | Logic-gated strand displacement circuits, miRNA-initiated HCR |

| Proteins/Enzymes | Telomerase, APE1 | Cancer, oxidative stress | Aptamer-based activation, enzyme-cleavable linker systems |

| Small Molecules | ATP, cAMP | Metabolic state, signaling pathways | Aptamer- or riboswitch-integrated circuits |

| Metal Ions | Zn²⁺, Ca²⁺ | Neurological signaling, homeostasis | Ion-specific DNAzymes as catalytic units |

Performance Metrics of Recent Systems

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Representative DNA Biosensors

| Sensor Type | Detection Trigger | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Response Time | Signal-to-Background Ratio | Reference (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNAzyme Cascade | Intracellular Zn²⁺ | ~1.2 µM | 30-60 min | >10-fold | (Ma, 2022) |

| Aptamer-CHA | ATP in cells | ~200 µM | ~20 min | ~8-fold | (Zhao, 2023) |

| miRNA-HCR | miR-21 | ~50 pM | 2-4 hours | >15-fold | (Wu, 2024) |

| Telomerase-Initiated Circuit | Telomerase activity | <10 cancer cells | ~90 min | >20-fold | (Chen, 2023) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Transfection and Live-Cell Imaging of an mRNA-Triggered HCR Biosensor

Objective: To detect and visualize specific mRNA expression in live HeLa cells using a hybridization chain reaction (HCR) system.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Procedure:

- DNA Probe Design & Preparation:

- Design two metastable DNA hairpin probes (H1, H2) with fluorophore/quencher pairs (e.g., FAM/BHQ1). Include a toehold domain in H1 complementary to the target mRNA sequence.

- Synthesize and HPLC-purify all oligonucleotides.

- Resuspend hairpins in nuclease-free TE buffer to 100 µM. Anneal separately by heating to 95°C for 2 min and cooling slowly to room temperature over 60 min.

- Dilute annealed hairpins to 5 µM working concentration in sterile PBS.

Cell Seeding & Transfection:

- Seed HeLa cells in a glass-bottom 35 mm culture dish at 70% confluence 24h before transfection.

- For each dish, prepare a transfection complex: Mix 10 µL of Lipofectamine 3000 reagent with 125 µL Opti-MEM. In a separate tube, mix 5 µL of the 5 µM H1 probe and 5 µL of the 5 µM H2 probe with 5 µL P3000 reagent and 125 µL Opti-MEM.

- Combine the two mixtures, incubate for 15 min at RT, then add dropwise to cells in 1.5 mL of fresh, antibiotic-free medium.

- Incubate cells at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for 4-6 hours.

Live-Cell Imaging & Analysis:

- Replace transfection medium with fresh, pre-warmed live-cell imaging medium.

- Mount dish on a confocal microscope equipped with a environmental chamber (37°C, 5% CO₂).

- Acquire fluorescence images using appropriate laser/excitation for the fluorophore (e.g., 488 nm for FAM) at regular intervals (e.g., every 30 min for up to 24h).

- Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, Fiji) to quantify mean fluorescence intensity in the cell cytoplasm over time, normalizing to background and untransfected controls.

Protocol: In Vitro Characterization of a DNAzyme Logic Gate

Objective: To validate the function and kinetics of a Zn²⁺-dependent DNAzyme AND-gate circuit in a cell-free buffer system.

Procedure:

- DNAzyme Circuit Assembly:

- Synthesize the enzyme strand (E) and substrate strand (S) bearing a fluorophore and quencher. Include a complementary "mask" strand for the enzyme's catalytic core.

- Assemble the inactive complex by mixing E, S, and the mask strand in a 1:1.2:1.5 ratio in reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.2). Anneal from 80°C to 25°C over 45 min.

- Kinetic Analysis:

- Aliquot 98 µL of the assembled circuit (final concentration 50 nM) into a 96-well black plate.

- Initiate the reaction by adding 2 µL of a 100x stock solution of Zn²⁺ (to final desired concentration, e.g., 0, 1, 5, 10 µM) and a second input molecule (if required by the AND gate logic).

- Immediately place the plate in a fluorescence plate reader pre-heated to 37°C.

- Measure fluorescence (e.g., Ex/Em: 490/520 nm) every 30 seconds for 2 hours.

- Plot fluorescence vs. time. Calculate the reaction velocity (slope of initial linear phase) and plateau value for each condition to determine sensitivity and dynamic range.

Visualizations

Title: HCR Mechanism for mRNA Detection

Title: DNA-Based AND Logic Gate Operation

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function/Role | Key Considerations & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Chemically-modified Oligonucleotides | Functional units (probes, substrates, enzymes) of the network. | Backbone Modifications (PS) for nuclease resistance. Fluorophores/Quenchers (FAM/Cy3/BHQ1) for reporting. 2'-OMe/2'-F RNA bases for serum stability. |

| Lipid-Based Transfection Reagents | Deliver DNA networks across cell membrane. | Must balance efficiency with cytotoxicity. e.g., Lipofectamine 3000, RNAiMAX. Cell-type optimization is critical. |

| Nuclease-Free Buffers & Water | Prevent degradation of DNA components during preparation. | Essential for maintaining probe integrity before cellular entry. |

| Live-Cell Imaging Medium | Maintain cell health during prolonged imaging. | Phenol-red free, with appropriate serum and buffer (e.g., HEPES). |

| Confocal Microscopy System | High-resolution, spatial-temporal imaging of intracellular signals. | Requires sensitive detectors (e.g., GaAsP PMTs), environmental control, and appropriate filter sets. |

| Fluorescence Plate Reader | Quantify bulk kinetic performance in cell-free or cell-based assays. | Enables high-throughput screening of circuit parameters and conditions. Temperature control is essential. |

Application Notes

This document details protocols and considerations for engineering synthetic multicellular patterning using DNA nanostructure-based communication networks. The goal is to create designer cell collectives that self-organize into defined spatial patterns, mimicking developmental biology for applications in synthetic morphogenesis, smart drug delivery consortia, and advanced tissue engineering.

- Core Principle: Cells are engineered to display specific DNA nanostructures (e.g., origami-based signal senders, receivers, and logic gates) on their surfaces. Communication is mediated by diffusible oligonucleotide strands or membrane-tethered strand displacement reactions, enabling precise, programmable, and orthogonal signaling.

- Key Advantage over Natural Systems: DNA-based communication offers unprecedented modularity. Signal identity, strength, diffusion range, and processing logic (AND, OR, NOT gates) can be rationally designed by tuning strand sequences, nanostructure geometry, and reaction kinetics.

- Thesis Context: This work directly extends the thesis "Building artificial molecular communication networks with DNA nanostructures" from single-cell or population-level behaviors to the emergent, spatially organized tissue scale. It addresses the critical challenge of scaling molecular programming to orchestrate collective cellular behavior in space.

Table 1: Key Parameters for DNA-Based Patterning Elements

| Parameter | Typical Range/Value | Function/Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Oligo Length | 20-40 nt | Balances diffusion rate, specificity, and degradation susceptibility. |

| Signal Concentration | 1-100 nM (extracellular) | Determines effective signaling range and activation threshold. |

| Membrane Anchor (Lipid-Tag) | Diacylglycerol, Cholesterol | Tethers sender/receiver nanostructures to the plasma membrane. |

| Pattern Resolution | 50-200 μm (cell-diameter scale) | Dictated by signal diffusion coefficient and degradation rate. |

| Pattern Formation Time | 6-48 hours | Dependent on cell growth, signal production/response kinetics. |

| Communication Orthogonality | >5 parallel channels demonstrated | Enables complex multi-lineage patterning; set by sequence design. |

Table 2: Comparison of Signal Relay Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Description | Speed | Spatial Effect | Design Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive Diffusion | Free oligonucleotides diffuse from sender cells. | Fast (µm²/s) | Smooth gradients, broad patterns. | Low |

| Catalytic Relay (HCR) | Receivers amplify & relay signal via hybridization chain reaction. | Medium | Sharpens boundaries, extends range. | Medium |

| Membrane-Tethered Transfer | Signal transfer via direct cell-cell contact or nanostructure interaction. | Slow | Precise, contact-dependent patterning. | High |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Lipid-Functionalized DNA Sender/Receiver Nanostructures

Objective: Produce DNA origami tiles functionalized with membrane-anchoring lipids and output/input DNA strands. Materials: M13mp18 scaffold, staple strands, cholesterol-TEG-modified staples, Cy3/Cy5-labeled output/input strands, magnesium-containing buffer (TAE/Mg2+), spin filters. Procedure:

- Annealing: Mix scaffold (2 nM) with a 10x excess of unmodified staples, cholesterol staples (2-4 per origami), and signaling strands (5x excess) in 1x TAE with 12.5 mM MgCl₂. Use a thermal cycler: 80°C to 60°C at -1°C/min, 60°C to 24°C at -0.1°C/min.

- Purification: Purify assembled structures using 100 kDa molecular weight cut-off spin filters (3x, 5000 rcf) with purification buffer (1x TAE, 11 mM MgCl₂).

- Characterization: Verify assembly and labeling via agarose gel electrophoresis (2% gel, 0.5x TBE, 11 mM MgCl₂, 70V, 90 min) and fluorescence imaging.

Protocol 2: Cell Surface Functionalization & Co-culture Patterning Assay

Objective: Create a sender cell population that secretes a signal and a receiver cell population that changes fluorescence upon signal detection, then co-culture to form patterns. Materials: HEK293T or designer mammalian cells, serum-free medium, transfection reagent (for genetic parts if used), purified DNA sender/receiver nanostructures (from Protocol 1), live-cell imaging chamber. Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Seed two separate populations of cells at 70% confluence in 24-well plates.

- Functionalization: For Sender Cells, incubate with 2 nM lipidated DNA sender nanostructures in serum-free medium for 2 hours at 37°C. For Receiver Cells, incubate with 2 nM lipidated DNA receiver nanostructures containing a quenched fluorescence reporter.

- Pattern Initiation: Trypsinize, count, and mix cells at a defined ratio (e.g., 1:10 sender:receiver). Spot 10 µL of the mixed cell suspension (~2000 cells) onto the center of a fibronectin-coated live-cell imaging chamber.

- Pattern Incubation & Imaging: Allow cells to adhere for 1 hour, then gently add 1 mL of pre-warmed culture medium. Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂. Acquire time-lapse fluorescence and brightfield images every 30 minutes for 48 hours using a confocal or widefield microscope.

Protocol 3: Quantifying Patterning Boundaries

Objective: Analyze microscopy data to quantify pattern sharpness and spatial organization. Materials: Time-lapse image stacks (TIFF format), ImageJ/Fiji software. Procedure:

- Image Segmentation: Apply a Gaussian blur and threshold to segment individual cells in the brightfield channel.

- Signal Intensity Mapping: Measure the mean fluorescence intensity (e.g., from the receiver's activated reporter) for each segmented cell.

- Spatial Analysis: Plot fluorescence intensity vs. radial distance from the center of the sender cell cluster. Fit the resulting profile to a sigmoidal function. The boundary sharpness is defined as the distance over which the signal intensity drops from 90% to 10% of its maximum.

Visualization Diagrams

Diagram 1: DNA-based cell-to-cell signal transduction.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for synthetic patterning.

Diagram 3: Radial pattern formation via a signal relay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for DNA Nanostructure-Based Patterning

| Item | Function | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Custom Oligonucleotide Pools | Source of staple strands and signaling oligos. Requires HPLC purification. | IDT, Eurofins Genomics |

| M13mp18 Phagemid | Standard scaffold strand for DNA origami. | Bayou Biolabs, NEB |

| Cholesterol-TEG Phosphoramidite | Chemical modifier for creating membrane-anchoring staple strands. | Glen Research |

| 100 kDa MWCO Spin Filters | Critical for purifying assembled DNA nanostructures from excess staples. | Amicon Ultra, Millipore |

| Live-Cell Imaging Chamber | Enables stable, long-term imaging with environmental control. | µ-Slide, Ibidi |

| Fluorescent DNA Labels (Cy3, Cy5, ATTO) | For visualizing nanostructure localization and signal activation. | ATTO-TEC, Lumiprobe |

| Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX | Alternative for transfecting genetic circuits that express nanostructure components. | Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| Mathematical Patterning Models (e.g., Reaction-Diffusion Solvers) | Software for predicting pattern outcomes. | COMSOL, custom Python scripts (Morpheus) |

Overcoming Noise and Leakage: Troubleshooting DNA Network Fidelity and Stability

Application Notes: Pitfalls in Artificial DNA Molecular Communication Networks

Building robust artificial molecular communication networks with DNA nanostructures requires meticulous attention to three primary failure modes. These systems aim to replicate natural signal transduction but are built from synthetic components like DNA walkers, logic gates, and amplifiers.

Signal Degradation refers to the loss of signal fidelity or strength as it propagates through the network. In DNA systems, this is often due to enzymatic degradation by nucleases, inefficient strand displacement kinetics, or leakage reactions that deplete fuel strands. Recent studies (2024) show that signal loss in multi-layer DNA cascade circuits can exceed 60% after just three amplification steps under suboptimal conditions.

Off-Target Binding occurs when DNA strands interact with unintended partners due to sequence homology or structural promiscuity. This is exacerbated in complex biological environments like cell lysates or serum, where non-cognate genomic DNA or RNA can interact. Analysis of toehold-mediated strand displacement systems indicates that even a single base-pair mismatch in the toehold region can reduce specificity by only ~10-100 fold, while perfect match rates are on the order of 10^6 M⁻¹s⁻¹.

Nonspecific Activation involves the initiation of a signaling pathway without the prescribed input, often due to environmental triggers like temperature fluctuations, nonspecific protein adsorption, or magnesium concentration changes. In DNAzyme-based systems, nonspecific cleavage rates can be as high as 0.05 hr⁻¹ even in the absence of the specific cofactor, leading to high background noise.

Table 1: Measured Impacts and Causes of Key Pitfalls in DNA Communication Networks

| Pitfall | Typical Measured Impact | Primary Causes | Common Experimental Readout |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Degradation | 40-70% signal loss over 3-5 steps | Nuclease activity, slow kinetics, reactant depletion | Fluorescence quenching over time (FRET efficiency drop) |

| Off-Target Binding | 10-100x reduction in specificity per mismatch | Sequence homology, stable secondary structures | Gel shift assays showing multiple bands; qPCR off-rate changes |

| Nonspecific Activation | Background signal 5-20% of max activation | Thermal breathing, contaminant metals, protein adsorption | Fluorescence increase in negative controls (No-input baselines) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 2.1: Quantifying Signal Degradation in a DNA Cascade Amplifier

Objective: Measure signal retention through a three-layer DNA strand displacement cascade. Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table. Procedure:

- Prepare Layers: Separately anneal the three component complexes (C1, C2, C3) in Tris-EDTA-Mg²⁺ buffer (TEMg) by heating to 95°C for 5 min and cooling at 0.1°C/s to 25°C.

- Baseline Measurement: In a black 384-well plate, mix 50 nM of the final output reporter complex (FAM-quencher pair) with TEMg buffer. Measure initial fluorescence (λex/λem = 492/517 nm) for 5 min.

- Cascade Assembly: Sequentially add pre-annealed C1, C2, and C3 to final concentrations of 10 nM each in the well. Do not add input trigger.

- Initiate Cascade: Add input DNA trigger to a final concentration of 5 nM. Immediately begin kinetic fluorescence reading every 30 sec for 120 min at 25°C.

- Data Analysis: Fit the fluorescence curve for each layer's expected activation time. Calculate the efficiency as (Max signal at layer N) / (Theoretical max from layer N-1 signal). Efficiency <85% per layer indicates significant degradation.

Protocol 2.2: Assessing Off-Target Binding via Gel Shift Competition

Objective: Evaluate the specificity of a toehold-mediated strand displacement reaction against single-base mismatch targets. Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table. Procedure:

- Prepare Reactions: In separate tubes, combine 100 nM of the labeled output complex with 500 nM of either the perfectly matched (PM) trigger or one of three single-mismatch (MM1, MM2, MM3) triggers in 1X TEMg buffer.

- Incubate: Hold reactions at 25°C for 2 hours to reach equilibrium.

- Non-Denaturing Gel Electrophoresis: Load each reaction onto a pre-run 10% polyacrylamide gel (0.5X TBE, 4°C). Run at 80 V for 60 min.

- Imaging: Visualize using a gel imager for the fluorophore label (e.g., Cy5). Quantify band intensities for bound vs. unbound complexes.

- Calculate Specificity: For each MM trigger, calculate the ratio: (Bound fraction for PM) / (Bound fraction for MM). A ratio <100 suggests high off-target risk.

Protocol 2.3: Measuring Nonspecific Activation in a DNAzyme Network

Objective: Determine the background cleavage rate of a Mg²⁺-dependent DNAzyme in the absence of its specific cofactor (Mg²⁺) and in the presence of common biological contaminants. Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table. Procedure:

- Prepare Test Environments: In four tubes, prepare the substrate-reporter construct (100 nM) in: (A) Pure TEMg (2 mM Mg²⁺), (B) Mg²⁺-free buffer (with 0.5 mM EDTA), (C) Buffer with 1 mM Ca²⁺, (D) 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) in TEMg.

- Initiate Reaction: Add DNAzyme to each tube to a final concentration of 50 nM. Do not add the primary trigger strand.

- Monitor: Transfer to a 384-well plate and measure fluorescence (for FAM cleavage) every 5 minutes for 24 hours at 37°C.

- Analyze: Fit the initial linear portion of the fluorescence increase for each condition. The slope represents the nonspecific activation rate. Compare Condition A (positive control with Mg²⁺) to B, C, D to identify contaminant-driven activation.

Visualization Diagrams

Diagram Title: DNA Network Pathway and Interfering Pitfalls

Diagram Title: Integrated Workflow for Multi-Pitfall Testing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for DNA Communication Network Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function & Role in Mitigating Pitfalls | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Pure, HPLC-Purified DNA Oligos | Minimizes off-target binding by ensuring correct sequence and removing truncations. Essential for all core components. | Synthesized with 5nmole scale, HPLC purification, desalted. |

| High-Fidelity Thermostable Polymerase | For enzymatic circuit amplification (e.g., RCA). Low error rate reduces mutation-induced off-target effects. | Phi29 or Vent (exo+) DNA polymerase. |

| Nuclease-Free Buffers with Mg²⁺ Control | Prevents nonspecific degradation and controls DNAzyme/strand displacement kinetics. Mg²⁺ concentration is critical. | Tris-EDTA-Mg²⁺ (TEMg) buffer, pH 8.0, 0.1µm filtered. |

| Fluorescent-Quencher Probe Pairs (FRET) | Enables real-time, quantitative measurement of signal propagation and degradation. | Dual-labeled oligos (e.g., FAM/BHQ-1, Cy5/Iowa Black RQ). |

| Mismatch & Competitor DNA Libraries | For specificity testing. Designed with systematic variations to challenge network fidelity. | Pools of oligos with 1-3 base mismatches or random sequences. |

| Surface Passivation Agents | Reduces nonspecific adsorption to tubes/plates, lowering background activation. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, molecular biology grade), PEGylated surfaces. |

| Magnetic Beads with Streptavidin | For pull-down assays to isolate and quantify off-target complexes from solution. | 1µm diameter, high-binding capacity (>500 pmol/mg). |

| Real-Time PCR System with Kinetic Read | Allows for high-throughput, multi-well kinetic monitoring of signal transduction. | Instrument capable of fluorescence reading every 30 seconds. |