Advanced Strategies for Improving Nanoparticle Stability in Physiological Fluids: From Surface Design to Clinical Application

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical challenge of nanoparticle instability in physiological fluids and the advanced strategies being developed to overcome it.

Advanced Strategies for Improving Nanoparticle Stability in Physiological Fluids: From Surface Design to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical challenge of nanoparticle instability in physiological fluids and the advanced strategies being developed to overcome it. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental interactions between nanoparticles and complex biological environments, including the formation of the protein corona. The scope ranges from foundational concepts of colloidal stability to methodological approaches for surface decoration, troubleshooting common optimization issues, and the vital validation through comparative analysis of different nanocarrier systems. By synthesizing recent advances in surface chemistry, stealth coatings, and characterization techniques, this review serves as a guide for designing next-generation, stable nanomedicines with enhanced therapeutic efficacy and safety profiles.

The Nanoparticle Stability Challenge: Understanding the Physiological Environment

Defining Colloidal Stability in High-Ionic-Strength Biological Fluids

FAQs on Nanoparticle Stability in Biological Environments

1. Why is colloidal stability a significant challenge in high-ionic-strength biological fluids? Biological fluids, such as blood and serum, have high ionic strengths. Nanoparticles stabilized primarily by electrostatic repulsion see their diffuse double layer compressed and neutralized under these conditions. This shields the repulsive forces between particles, leading to aggregation due to dominant van der Waals attractive forces [1]. This aggregation can alter the nanoparticle's biological identity, fate, and function.

2. What are the main strategies to stabilize nanoparticles in these environments? The two primary strategies are electrostatic stabilization and steric stabilization [1]. Electrostatic stabilization is often ineffective in high-salt environments. Steric stabilization, achieved by coating nanoparticles with polymers like polyethylene glycol (PEG), creates a physical barrier that prevents particles from coming into close contact, thus maintaining dispersion stability [1]. A combination, known as electrosteric stabilization, is also common.

3. What is the "protein corona" and how does it affect stability? When nanoparticles enter biological fluids, proteins and other biomolecules rapidly adsorb onto their surface, forming a layer called the "protein corona" [1]. This corona can cause two main issues: it can destabilize the nanoparticle dispersion, leading to aggregation, and it can inertize the surface, blocking targeting moieties and hindering the nanoparticle's intended biological function [1].

4. How can I experimentally test the stability of my nanoparticles in relevant fluids? A common and informative method is to use Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to monitor the nanoparticle size distribution over time after dispersing them in the biological fluid of interest (e.g., serum, gastric juice) [2]. An increase in hydrodynamic diameter indicates aggregation and poor colloidal stability. This provides a direct assessment of the formulation's physical stability before moving to complex in vivo studies [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Rapid Nanoparticle Aggregation in Cell Culture Media

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Tests | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Steric Stabilization | Measure hydrodynamic diameter (DLS) in water vs. PBS. Aggregation in PBS indicates salt sensitivity. [1] | Introduce a steric stabilizer like PEG or PVP via surface functionalization. [1] |

| Ionic Strength-Induced Double Layer Compression | Determine the Critical Coagulation Concentration (CCC) using DLS in salt solutions. [3] | Switch from electrostatic to steric stabilization strategies. [1] |

| Interaction with Serum Proteins | Incubate NPs with serum and measure size and zeta potential. A change confirms corona formation. [2] | Use "stealth" coatings like PEG to impart antifouling properties and minimize protein adsorption. [1] |

Problem 2: Loss of Targeting Ability Despite Stable Dispersion

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Tests | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Formation of a Protein Corona | Use flow cytometry with fluorescent reporter binders to map the availability of surface motifs in complex media. [4] | Optimize surface density of PEG or use zwitterionic ligands to create an antifouling surface. [1] |

| Surface Moieties Blocked by Stabilizing Ligands | Review surface chemistry strategy; the stabilizing ligand may be sterically hiding the targeting group. | Employ a heterofunctional PEG that has one end for stability and the other for bio-conjugation of targeting molecules. [1] |

Problem 3: Inconsistent Experimental Results Between Buffer and Biological Fluids

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Tests | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Nature of the Bio-interface | Characterize the nanoparticle-biomolecule complex directly in the biological milieu without isolation, using techniques like in-situ flow cytometry. [4] | Standardize pre-incubation protocols in relevant biological fluids to ensure a consistent and representative corona forms before application. [4] |

| Aggregation During Experimental Workflow | Use DLS to monitor size at each step of the protocol when NPs are transferred from buffer to complex media. [2] | Ensure a homogeneous dispersion before use. Consider adding steric stabilizers to the formulation to maintain stability across all steps. [1] |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials and Their Functions

The following table lists key reagents and materials used to study and improve nanoparticle colloidal stability in physiological environments.

| Item | Function in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A polymer ligand providing steric stabilization and antifouling properties in high-ionic-strength fluids. [1] | Molecular weight and surface density are critical for effective stealth properties and preventing protein adsorption. [1] |

| Thiol-terminated PEG (PEG-SH) | Used for covalent grafting onto noble metal (e.g., gold, silver) nanoparticle surfaces via strong Au-S bonds. [1] | Allows for a stable ligand shell that resists displacement in biological environments. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument | Measures the hydrodynamic diameter and size distribution of nanoparticles to monitor aggregation in real-time. [2] | Essential for quantifying colloidal stability in different fluids like salt solutions, serum, and tissue homogenates. [2] |

| Flow Cytometry with Fluorescent Reporters | Enables the detection and quantification of nanoparticle uptake by cells and the mapping of biomolecular corona motifs. [5] [4] | Requires fluorescently labelled nanoparticles. Allows for high-throughput, single-cell analysis of internalization. [5] |

| Zwitterionic Ligands | Provide an alternative to PEG for creating antifouling surfaces. They form a strong hydration layer via electrostatic interactions. [1] | Can offer superior stability and reduced immune response compared to some PEGylated systems. |

| Model Polystyrene Nanoparticles | Commercially available, well-characterized particles with uniform size and surface chemistry (e.g., carboxylated). [5] | Useful as a standard for method development and interlaboratory comparison of uptake and stability studies. [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Stability Assessment

Protocol 1: Assessing Colloidal Stability via Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

This protocol is adapted from methods used to test polymeric nanoparticle stability [2].

Objective: To determine the physical stability of nanoparticles in various biological fluids by monitoring their hydrodynamic size over time.

Materials:

- Nanoparticle suspension

- Biological fluids (e.g., simulated gastric juice, serum, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS))

- DLS instrument (e.g., Zetasizer Nano ZN)

Method:

- Preparation: Dilute the nanoparticle suspension 1:1 (v/v) with the biological fluid of interest. Ensure the sample is well-mixed.

- Baseline Measurement: Perform an initial DLS measurement of the nanoparticle suspension in its storage buffer to establish the baseline hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI).

- Incubation: Incubate the nanoparticle-biofluid mixture at 37°C under gentle agitation to simulate physiological conditions.

- Time-Course Measurement: Measure the hydrodynamic diameter and PDI of the mixture at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours) using DLS.

- Data Analysis: Plot the mean hydrodynamic diameter versus time. A significant increase in diameter indicates nanoparticle aggregation and poor colloidal stability in that specific fluid [2].

Protocol 2: Quantifying Nanoparticle Uptake in Cells by Flow Cytometry

This protocol summarizes a robust approach for quantifying the uptake of fluorescent nanoparticles, as established in interlaboratory comparisons [5].

Objective: To quantitatively measure the internalization of fluorescently labelled nanoparticles into cells.

Materials:

- Fluorescently labelled nanoparticles

- Cell line of interest

- Complete cell culture medium

- Flow cytometer

- Trypsin-EDTA, centrifuge, PBS

Method:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells in a multi-well plate and culture until they reach 70-80% confluence.

- Nanoparticle Exposure: Incubate cells with a range of concentrations of fluorescent nanoparticles in serum-containing medium for the desired time.

- Washing: After incubation, thoroughly wash the cells with PBS to remove non-internalized nanoparticles adhering to the cell membrane.

- Cell Harvesting: Gently trypsinize the cells and resuspend them in a flow cytometry buffer (e.g., PBS with 1% FCS).

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: Analyze at least 10,000 events per sample on the flow cytometer. Use untreated cells as a negative control to set the background fluorescence.

- Data Analysis: The fluorescence intensity of the cell population is proportional to the amount of internalized nanoparticles. Results can be expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) or the percentage of fluorescent-positive cells [5]. It is critical to confirm that the fluorescence signal originates from cell-internalized nanoparticles and not from free dye released into the medium [5].

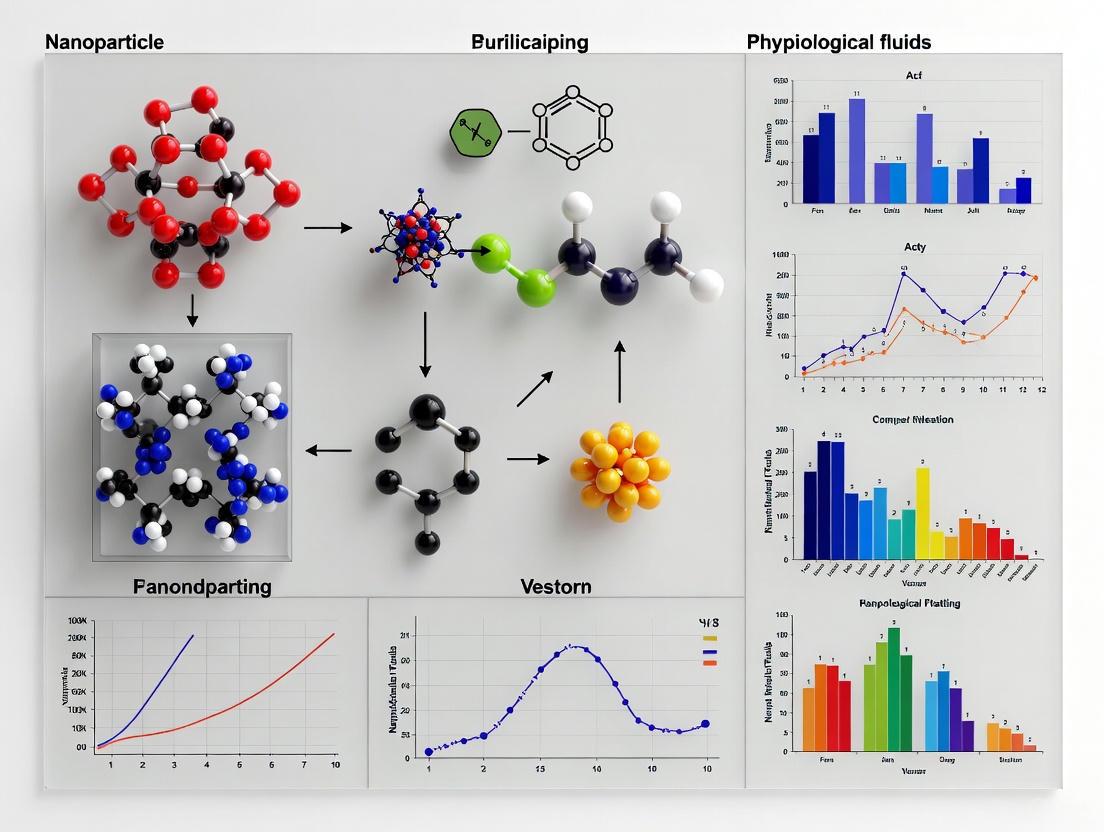

Stability Mechanisms and Experimental Workflow

Diagram 1: Challenges and stabilization path for nanoparticles in biological fluids.

Diagram 2: Workflow for evaluating nanoparticle colloidal stability and biological performance.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How does nanoparticle surface charge influence protein corona formation and subsequent cellular uptake? The surface charge of a nanoparticle is a primary determinant of its behavior in biological fluids. The vitreous humor presents a significant barrier to intravitreally injected nanoparticles, where the anionic nature of the gel, primarily due to hyaluronic acid, leads to charge-dependent immobilization [6]. Single-particle tracking studies show that cationic particles are almost completely immobilized in the vitreous through electrostatic interactions. In contrast, anionic and neutral formulations are generally mobile, though larger (>200 nm) neutral particles can have restricted diffusion [6]. This immobilization can enhance opsonization by making nanoparticles more visible to phagocytic cells. Surface modification, particularly PEGylation, can shield surface charge and increase the mobility of cationic and larger neutral formulations, thereby reducing undesirable binding and improving distribution to the target tissue [6].

FAQ 2: What experimental strategies can be employed to minimize opsonization and extend nanoparticle circulation time? A primary strategy to reduce opsonization is the use of surface coatings that create a stealth effect [7]. PEGylation, the attachment of polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains, is the most established method. It forms a hydrophilic, steric barrier that reduces the adsorption of opsonins and delays clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) [6] [7]. Beyond PEG, research into alternative shielding strategies is ongoing. For ocular delivery, an innovative approach involves pre-forming an artificial protein corona. One study demonstrated that coating a lipoplex (a drug delivery system) with an engineered corona made of fibronectin and a specific tripeptide effectively disguised the system from mucin binding in tears, significantly improving drug uptake into corneal epithelial cells [8]. This indicates that controlling the corona composition can steer biological interactions favorably.

FAQ 3: What are the critical factors affecting the stability of RNA-loaded lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) in biological fluids, and how can stability be assessed? The stability of RNA-LNPs is crucial for their therapeutic efficacy and is influenced by lipid composition, particle surface properties, and interactions with proteins in physiological conditions [7]. A key challenge is the balance between stability for delivery and the subsequent disassembly needed to release the RNA payload inside the target cell. The interplay between physiological stability, target specificity, and therapeutic efficacy is complex and must be carefully optimized for each formulation [7]. Assessment methods include:

- Dynamic Laser Scattering (DLS): For measuring particle size and polydispersity.

- Liquid Chromatography: For analyzing lipid and RNA integrity.

- Fluorescent and Radiolabeled Techniques: For tracking nanoparticle fate in vivo [7].

FAQ 4: Can protein corona formation be leveraged for beneficial applications in nanomedicine? Yes, the protein corona can be harnessed for diagnostic purposes. The corona forms a molecular fingerprint of the proteomic signature of its biological environment [9]. A recent study successfully used protein corona formation on gold nanoparticles (~20 nm) incubated with tear samples to detect choroidal melanoma. The disease state altered the composition of proteins adsorbed from tears onto the nanoparticles. By analyzing this corona with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) and machine learning, researchers could distinguish between healthy individuals and choroidal melanoma patients with high accuracy, showcasing a promising non-invasive diagnostic application [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Nanoparticle Aggregation and Instability in Physiological Fluids

Problem: Nanoparticles aggregate or degrade when introduced to biological fluids like serum or vitreous humor, leading to loss of function or premature payload release.

Solution: A multi-faceted approach focusing on formulation and surface engineering is required.

- Investigate Shielding Agents: Incorporate PEGylated lipids (e.g., DMG-PEG2000 or DSPE-PEG) into your formulation. For RNA-LNPs, a typical molar ratio is around 1.5% [10]. PEGylation creates a steric barrier that improves colloidal stability and reduces protein adsorption [6] [7].

- Optimize Lipid Composition: Enhance membrane rigidity and stability by using high-transition-temperature lipids like DSPC and incorporating cholesterol at ~38.5 mol% [10]. Cholesterol fills gaps in the lipid bilayer, improving packing and reducing permeability.

- Consider an Artificial Corona: For specific applications like ocular surface delivery, pre-coating nanoparticles with a designed protein corona (e.g., using fibronectin) can prevent undesirable interactions with biological components like mucin [8].

- Assess Stability Systematically: Monitor your formulation's stability using the following methods:

| Assessment Method | Parameter Measured | Protocol Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Hydrodynamic diameter, Polydispersity Index (PdI) | Resuspend nanoparticles in relevant biological fluid (e.g., simulated vitreous, serum) and measure size/PdI over time (e.g., 0, 1, 4, 24 hours). A stable formulation will show minimal change. [11] |

| Liquid Chromatography | Payload (e.g., RNA, drug) encapsulation efficiency & release kinetics | Use dialysis or centrifugal filters to separate released payload from encapsulated. Quantify the percentage of payload retained within nanoparticles over time in biological buffers. [7] [11] |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Morphology and physical integrity | Negative stain samples at various time points to visually confirm no aggregation, fusion, or structural disintegration has occurred. [11] |

Guide 2: Overcoming Rapid Clearance and Poor Target Engagement

Problem: Nanoparticles are quickly cleared from the site of administration (e.g., the eye) or circulation, failing to reach the therapeutic target.

Solution: Tailor nanoparticle properties to overcome specific biological barriers.

- For Intravitreal Delivery: Optimize Surface Charge and Size. The vitreous is a polyanionic gel. To ensure mobility:

- Use anionic or neutral formulations.

- Keep particle size below 200 nm.

- Avoid cationic surfaces, as they bind irreversibly to hyaluronic acid [6].

- For Topical Ocular Delivery: Enhance Corneal Retention and Penetration.

- Assess Ocular Biodistribution: To evaluate success, use in vivo models. A sample protocol involves:

- Synthesize fluorescently labeled nanoparticles (e.g., Cy5-labeled PLGA NPs) [11].

- Apply topically to the eyes of animal models.

- Euthanize at predetermined timepoints (e.g., 30 min, 1 h).

- Excise ocular tissues (cornea, sclera, retina, etc.) and quantify fluorescence to determine spatiotemporal distribution [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Analyzing Protein Corona Composition Using Mass Spectrometry

This protocol outlines the process for isolating and identifying proteins that form the corona on nanoparticles, based on research for disease detection [9].

Workflow Diagram: Protein Corona Analysis

Title: Protein Corona Isolation and Analysis Workflow

Materials:

- Gold nanoparticles (~20 nm) or your nanoparticle of interest.

- Source of biological proteins (e.g., human tear samples collected on Schirmer strips, blood serum) [9].

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS).

- Centrifugal filters (e.g., 100 kDa MWCO) or ultracentrifuge.

- Trypsin, for protein digestion.

- Mass Spectrometry system (e.g., ESI-MS).

Step-by-Step Method:

- Nanoparticle Incubation: Synthesize and characterize your nanoparticles (e.g., citrate-reduced AuNPs). Incubate a known concentration of nanoparticles with the biological fluid (e.g., diluted tear sample or serum) for a set duration (e.g., 1 hour) at 37°C to allow corona formation [9].

- Corona Isolation: Centrifuge the mixture at high speed (or use centrifugal filters) to pellet the nanoparticle-protein corona complexes. Carefully remove the supernatant.

- Washing: Resuspend the pellet in PBS and repeat the centrifugation/washing step at least three times to remove unbound and loosely associated proteins.

- Protein Digestion: Resuspend the final pellet and digest the hard corona proteins using trypsin to create peptides for analysis.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Inject the digested peptide mixture into an ESI-MS system to obtain mass-to-charge (m/z) and intensity data for protein identification [9].

- Data Analysis: Process the spectral data using bioinformatics software and machine learning algorithms to identify the proteins present and compare corona profiles between different experimental conditions (e.g., healthy vs. diseased) [9].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Nanoparticle Diffusion in a Complex Biological Gel

This protocol uses single-particle tracking to study how nanoparticles move through biological barriers like the vitreous humor [6].

Workflow Diagram: Single-Particle Tracking in Vitreous

Title: Nanoparticle Diffusion in Vitreous

Materials:

- Fluorescently labeled nanoparticles: Incorporate a lipophilic dye like Liss Rhod-PE (0.3 mol%) into the lipid bilayer during synthesis [6].

- Source of vitreous humor: Fresh or freshly frozen intact vitreous from bovine or porcine eyes.

- Single-particle tracking microscope: An epifluorescence or TIRF microscope equipped with a high-sensitivity EMCCD or sCMOS camera.

- Image analysis software: e.g., ImageJ with TrackMate or custom MATLAB/Python scripts.

Step-by-Step Method:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare your nanoparticle formulations with varying surface charges (anionic, cationic, neutral) and PEGylation states. Hydrate them in an appropriate buffer like HEPES-buffered saline [6].

- Vitreous Mounting: Carefully place an intact vitreous body into a sealed imaging chamber to prevent dehydration.

- Nanoparticle Injection: Use a micro-syringe to inject a small volume of nanoparticle suspension directly into the center of the vitreous body.

- Data Acquisition: Using the SPT microscope, acquire high-frame-rate videos (e.g., 10-100 fps) of multiple random locations within the vitreous.

- Particle Tracking: Use tracking software to reconstruct the trajectories of individual nanoparticles from the video data.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the mean squared displacement (MSD) for each trajectory. From the MSD, derive the diffusion coefficient (D) for hundreds of nanoparticles per formulation to statistically compare their mobility [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids (e.g., SM-102) | Key component of RNA-LNPs; positively charged at low pH for mRNA encapsulation, neutral at physiological pH for reduced toxicity. | Used in COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. Critical for self-assembly and endosomal escape [10]. |

| PEGylated Lipids (e.g., DMG-PEG2000, DSPE-PEG) | Provides a steric "stealth" shield; reduces protein adsorption and opsonization; improves stability and circulation time. | Typically used at 1.5-4 mol%. A balance must be struck as high PEG content can inhibit cellular uptake [6] [10]. |

| Helper Lipids (e.g., DSPC, DPPC) | Provides structural integrity to the lipid bilayer; enhances stability and facilitates fusion with cell membranes. | DSPC is a common, rigid helper lipid used in LNP formulations at ~10 mol% [6] [10]. |

| Cholesterol | Stabilizes the lipid bilayer; increases membrane packing and fluidity; enhances nanoparticle stability in vivo. | A standard component, often used at ~38.5 mol% in LNP formulations [10]. |

| Fluorescent Lipids (e.g., Liss Rhod-PE) | Labels lipid-based nanoparticles for visualization and tracking in in vitro and in vivo studies. | Incorporated at low molar ratios (e.g., 0.3%) to avoid altering nanoparticle properties [6]. |

| Polymeric Materials (e.g., PLGA) | Biodegradable and biocompatible polymer for sustained drug release; used in nanoparticles for encapsulation. | PLGA nanoparticles can protect labile drugs like Lutein from degradation and provide controlled release [11]. |

| Artificial Corona Proteins (e.g., Fibronectin + RGD peptide) | Pre-coating to create a defined biological identity; can be used to evade biological barriers or promote targeting. | Demonstrated to improve ocular drug delivery by preventing mucin binding and enhancing cellular uptake [8]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Nanoparticle Stability Issues in Physiological Fluids

This guide addresses frequent challenges researchers encounter when working with nanoparticles in physiological conditions, providing targeted solutions based on the critical physicochemical properties of size, surface charge, and hydrophobicity.

Problem 1: Rapid Clearance from Bloodstream

Issue: Nanoparticles are quickly removed from circulation before reaching the target tissue.

- Root Cause: Size is a primary factor. Particles larger than 200 nm may be sequestered by the spleen and liver, while very small particles (<10 nm) can undergo rapid renal clearance [14] [15].

- Solution: Optimize nanoparticle size. For long circulation, a size of approximately 100 nm is often ideal as it balances the avoidance of organ filtration with the ability to extravasate through the leaky vasculature of tumors via the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect [14]. Consider developing size-switchable nanoparticles that are larger during circulation (~100 nm) but shrink to a smaller size (~10 nm) upon reaching the target site in response to triggers like low pH or specific enzymes [14].

Problem 2: Poor Cellular Uptake

Issue: Nanoparticles reach the target tissue but are not efficiently internalized by cells.

- Root Cause: This is heavily influenced by surface charge and hydrophobicity. Positively charged nanoparticles typically show higher cellular internalization because they interact more readily with the negatively charged cell membrane [16]. Moderate hydrophobicity can also facilitate interaction with and penetration through the cell membrane [16] [17].

- Solution: For transcellular transport, design nanoparticles with a positive surface charge and hydrophobic surface properties [16]. If the nanoparticle must first penetrate a mucus layer (e.g., in oral delivery), a slightly negative charge and moderate hydrophilicity are beneficial for the initial step [16]. Surface functionalization with targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides) can further enhance specific uptake via active targeting [18].

Problem 3: Aggregation in Biological Fluids

Issue: Nanoparticles aggregate when introduced into physiological fluids (e.g., blood, cell culture media), leading to inconsistent behavior and potential vessel occlusion.

- Root Cause: Loss of colloidal stability due to interactions with high ionic strength electrolytes and biomolecules. The surface charge (Zeta potential (ζ)), if too low in magnitude, may be insufficient to provide electrostatic repulsion between particles [3] [19].

- Solution: Ensure a high magnitude of Zeta potential (typically > |±25| mV) for electrostatic stabilization [19]. Employ steric stabilization by coating nanoparticles with hydrophilic polymers like polyethylene glycol (PEG) or using dense coatings like polysaccharides (e.g., carboxymethyl chitosan) [16] [3]. This creates a physical barrier that prevents particles from coming close enough to aggregate.

Problem 4: Unintended Protein Corona Formation

Issue: Proteins in biological fluids spontaneously adsorb onto the nanoparticle surface, altering its intended biological identity, targeting capability, and charge.

- Root Cause: All nanoparticles introduced into a biological milieu will interact with proteins. The composition of this "protein corona" is dictated by the nanoparticle's hydrophobicity and surface charge [14] [17].

- Solution: Engineer a "stealth" surface to minimize nonspecific protein adsorption. A dense layer of PEG (PEGylation) is a common strategy [14] [18]. Alternatively, surface functionalization with hydrophilic biomolecules like human serum albumin can also reduce opsonization and improve biocompatibility [18].

Problem 5: Inconsistent Experimental Results Between Media

Issue: Nanoparticle properties (size, Zeta potential) measured in water differ significantly from those in biological fluids, leading to poor extrapolation of results.

- Root Cause: The physicochemical properties of nanoparticles are highly dependent on their dispersion medium. Factors like pH, ionic strength, and the presence of biomolecules in cell culture media or biological fluids profoundly affect their stability and apparent size [20].

- Solution: Always characterize nanoparticles (size, ζ-potential, stability) in the relevant physiological dispersion media (e.g., PBS, cell culture media, serum) that will be used in experiments, not just in pure water [20]. This provides a more realistic prediction of their behavior in a biological context.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How do I quantitatively measure nanoparticle hydrophobicity?

Unlike molecular compounds, nanoparticles cannot be characterized by standard methods like log P. A reliable method involves measuring the binding affinity of nanoparticles to a set of engineered collectors (surfaces) with tuned hydrophobicity. The adsorption kinetics to these different surfaces, often measured via Dark-Field microscopy, are used to calculate the surface energy components and provide a quantitative measure of hydrophobicity [17].

What is the "ideal" surface charge for in vivo applications?

There is no universal ideal charge, as it depends on the biological barrier. For penetrating the small intestinal mucus layer, a low-magnitude negative charge is beneficial. However, once through the mucus, a positive surface charge helps with transcellular transport across the intestinal epithelium [16]. For systemic circulation, a near-neutral or slightly negative charge can help reduce non-specific interactions with blood components and cell membranes [14] [18].

My nanoparticles are toxic to cells. How can I improve biocompatibility?

Cytotoxicity is often linked to size (smaller particles can be more toxic) and surface charge (highly positive charges can disrupt cell membranes) [14] [15]. To mitigate this:

- Increase size if possible, within the effective range.

- Moderate the surface charge or apply a shielding coating.

- Functionalize the surface with biocompatible molecules like PEG or human serum albumin to create a more biological-friendly interface [18].

How does nanoparticle shape influence performance?

Shape significantly impacts cellular uptake, blood circulation, and biodistribution. For instance, spherical nanoparticles are generally internalized by cells more easily and quickly than rod-shaped or fiber-like nanoparticles. Furthermore, small spherical nanoparticles have been shown to accumulate in tumors more effectively than larger spherical nanoparticles or their rodlike or wormlike counterparts [14] [15].

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Stability in Physiological Fluids

Objective

To evaluate the colloidal stability of nanoparticles in simulated physiological conditions by monitoring changes in hydrodynamic size and surface charge over time.

Materials and Reagents

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Provides a physiologically relevant ionic strength to test electrostatic stability [20]. |

| Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) | Complex cell culture media containing salts, vitamins, and amino acids to simulate in vitro environment [20]. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Source of proteins to study protein corona formation and its impact on stability [20] [7]. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument | To measure the hydrodynamic diameter and size distribution (polydispersity index) of nanoparticles [19] [18]. |

| Zeta Potential Analyzer | To measure the electrostatic potential at the nanoparticle surface, indicating colloidal stability [19] [18]. |

Methodology

- Nanoparticle Dispersion: Prepare standardized stock dispersions of your nanoparticles in pure water.

- Media Preparation: Dilute the nanoparticle stock into three different media to a final concentration typical for your application:

- Medium 1: PBS (pH 7.4)

- Medium 2: DMEM (or other relevant cell culture media)

- Medium 3: DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS

- Incubation: Incate the samples at 37°C under gentle agitation to simulate physiological temperature and flow.

- Time-point Measurement: At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours), withdraw aliquots from each sample.

- DLS Analysis: Measure the hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PdI). A stable formulation will show minimal change in size and a low PdI over time. An increase in size indicates aggregation.

- Zeta Potential Measurement: Measure the ζ-potential. A high magnitude (typically > |±25| mV) suggests good electrostatic stability, while a shift towards zero can predict instability [19].

- Data Interpretation: Correlate the changes in size and ζ-potential with the composition of the dispersion medium. Instability in PBS suggests sensitivity to ionic strength. Further instability in serum-containing media indicates significant protein corona formation.

The workflow for this experiment is outlined below.

Property Interplay and Stability Mechanisms Diagram

The stability and performance of nanoparticles in physiological fluids are governed by the interplay of their core physicochemical properties and the biological environment. The following diagram summarizes these key relationships and the primary stabilization mechanisms.

Fundamental Concepts: Why Nanoparticle Stability Matters in Physiological Fluids

For researchers in nanomedicine, achieving stable nanoparticle dispersions in biological fluids is not a mere formulation detail; it is a fundamental prerequisite for successful diagnostic and therapeutic outcomes. This guide addresses the core instability issues—aggregation, rapid clearance, and reduced efficacy—that can derail an otherwise promising nano-based application.

The Core Stability Challenge

Upon introduction to physiological fluids, nanoparticles encounter a complex environment characterized by high ionic strength and a high concentration of biomacromolecules, notably proteins [1]. This environment directly challenges colloidal stability through two primary mechanisms:

- Electrostatic Destabilization: Nanoparticles stabilized by electrostatic repulsion (e.g., citrate-capped gold nanoparticles) see their electrical double layer compressed and neutralized in high-salt environments. This neutralization van der Waals forces to dominate, leading to rapid aggregation [1].

- Protein Corona Formation: Proteins in biological fluids can adsorb onto the nanoparticle surface, forming a "protein corona" [1]. This corona can cause two major problems: it can lead to particle destabilization and aggregation, and it can mask surface functional groups, rendering targeting ligands ineffective and leading to surface "inertization" [1].

Direct Consequences: The Instability Cascade

The interplay of these challenges triggers a cascade of negative consequences, as illustrated below.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs and Solutions

This section addresses specific, high-priority issues researchers face during experiments.

FAQ: My nanoparticles aggregate immediately in cell culture media. How can I prevent this?

Root Cause: Standard cell culture media contain salts and serum, creating a high-ionic-strength environment with abundant proteins that destabilize electrostatically stabilized nanoparticles [1].

Solutions:

- Implement Steric Stabilization: Replace electrostatic stabilizers (e.g., citrate) with steric stabilizers that create a physical barrier. The most common and effective strategy is PEGylation—the covalent attachment of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) to the nanoparticle surface [1]. PEG's high hydrophilicity forms a hydrated layer that provides excellent steric stabilization and antifouling properties.

- Use Polymeric Stabilizers: Incorporate stabilizers like poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) (PVP) during synthesis or formulation. PVP has been shown to efficiently prevent gold nanoparticle aggregation even in challenging environments like silica aerogel synthesis, which can serve as a model for complex biological matrices [21].

- Consider Zwitterionic Ligands: For an even smaller hydrodynamic footprint, explore zwitterionic coatings. These ligands can prevent serum protein adsorption and are associated with high solubility and a small hydrodynamic diameter, which is beneficial for clearance and targeting [22].

FAQ: My nano-formulation shows rapid blood clearance, limiting its delivery to the target tissue. What factors should I investigate?

Root Cause: Rapid clearance is primarily mediated by the Mononuclear Phagocyte System (MPS), which quickly recognizes and removes opsonized nanoparticles from circulation [23] [24]. Non-stealth nanoparticles can be cleared within minutes [24].

Solutions and Factors to Investigate:

- Surface Coating (The "Stealth" Effect): PEGylation is the gold standard for prolonging circulation. It reduces opsonin adsorption, delaying recognition by phagocytic cells in the liver and spleen [23] [1]. Note that the PEG chain length, shape, and surface density are critical parameters [23].

- Hydrodynamic Diameter (HD): The in vivo HD, which includes the core, coating, and any adsorbed corona, is a master regulator of biodistribution. The MPS preferentially clears larger particles. Furthermore, for renal clearance, the filtration-size threshold is sharply defined: particles with an HD < 6 nm are typically filtered, while those > 8 nm are generally not [22]. Aim for a size that avoids both rapid renal filtration and MPS uptake.

- Surface Charge: Strongly cationic or anionic charges can promote serum protein adsorption, increasing the effective HD and accelerating clearance [22]. A neutral or zwitterionic surface is generally preferred for long circulation [22] [25].

Table 1: Key Nanoparticle Properties Affecting Pharmacokinetics and Targeting

| Property | Impact on Clearance & Biodistribution | Optimal Range for Long Circulation |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrodynamic Diameter (HD) | Determines renal filtration threshold (<6 nm) and MPS uptake (>10-100 nm) [22] [23]. | 10-100 nm to utilize EPR effect while avoiding rapid renal clearance [25]. |

| Surface Charge | Charged surfaces ( cationic or anionic) promote opsonization; neutral surfaces evade immune recognition [22] [25]. | Near-neutral (zeta potential ~0 mV) [22]. |

| Surface Coating | PEG and other hydrophilic polymers provide a "stealth" effect by reducing protein adsorption [23] [1]. | High-density PEGylation or zwitterionic coatings [22] [1]. |

FAQ: Despite good in vitro performance, my nanoparticles show reduced efficacy in vivo. Why?

Root Cause: This common problem often stems from a failure to overcome biological barriers in a living system, leading to insufficient drug delivery to the target site [26].

Solutions and Considerations:

- Leverage the EPR Effect: Solid tumors often have leaky vasculature and impaired lymphatic drainage, leading to the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect. Nanoparticles in the 10-200 nm size range can passively accumulate in these tissues [26] [25]. Ensuring long circulation time (via stealth coatings) is key to taking full advantage of the EPR effect [23].

- Account for the Protein Corona: The biocorona formed in vivo may be different from that formed in simplified in vitro models. This corona can sterically hinder active targeting ligands (antibodies, peptides) attached to the nanoparticle surface, effectively nullifying the targeting strategy [1]. Employing dense PEG brushes can help mitigate this issue.

- Investigate Novel Clearance Pathways: Recent research using intravital microscopy has revealed that large nanoparticles (~140 nm) that do not meet the size criteria for glomerular filtration can still be excreted by the kidneys via translocation through renal tubule cells [25]. This non-traditional pathway could be a significant factor in the rapid loss of some nano-formulations.

Essential Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: PEGylation of Citrate-Stabilized Gold Nanoparticles for Enhanced Stability

This protocol describes a robust ligand-exchange method to impart steric stabilization and antifouling properties to gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) [1].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Procedure:

- Materials: Citrate-stabilized AuNPs, thiol-terminated PEG (PEG-SH) of desired molecular weight (e.g., 5-10 kDa), ultrapure water, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- PEG-SH Solution: Prepare an aqueous solution of PEG-SH. The required concentration depends on the target surface coverage and nanoparticle size [1].

- Ligand Exchange: Under gentle stirring, add the PEG-SH solution dropwise to the citrate-stabilized AuNP solution.

- Incubation: Allow the reaction to proceed for 12-24 hours at room temperature to ensure complete ligand exchange.

- Purification: Remove excess PEG-SH by centrifuging the nanoparticle solution at their appropriate centrifugal force. Carefully decant the supernatant.

- Re-dispersion: Re-disperse the PEGylated AuNP pellet in the desired buffer (e.g., PBS) via gentle vortexing and sonication.

- Characterization: Confirm successful PEGylation by:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): An increase in hydrodynamic diameter and maintained monomodal distribution.

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: A minimal red-shift (< 5 nm) of the surface plasmon resonance peak indicates no aggregation.

- Stability Test: Challenge the nanoparticles by adding salt (e.g., to 0.15 M NaCl). PEGylated AuNPs should remain dispersed, while citrate-stabilized ones will aggregate and show a significant spectral shift [1].

Protocol: Evaluating Colloidal Stability in Biological Media

This method assesses the stability of nanoparticle formulations under physiologically relevant conditions.

Procedure:

- Preparation: Dilute the purified nanoparticle stock into a complete biological medium (e.g., cell culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum) to a final volume of 1 mL [21] [1].

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture at 37°C for the desired duration (e.g., 1, 4, 24 hours).

- Analysis: Monitor stability using one or more of the following techniques:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Measure the hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI) over time. A significant increase in size or PDI indicates aggregation [27] [28].

- UV-Vis-NIR Spectroscopy: For plasmonic nanoparticles, track the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) peak. Broadening or a red-shift indicates aggregation and particle growth [21].

- Visual Inspection: Observe the solution for a color change or precipitate formation, which are clear signs of instability [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Nanoparticle Stabilization and Characterization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Thiol-Polyethylene Glycol (PEG-SH) | Covalently binds to gold and other surfaces to provide steric stabilization and stealth properties [1]. | Molecular weight (2-20 kDa) affects chain density and steric coverage; functional end-groups (e.g., -COOH, -NH2) allow for further conjugation [23] [1]. |

| Poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) (PVP) | A polymeric stabilizer that adsorbs to nanoparticle surfaces, preventing aggregation via steric hindrance [21]. | Effective at preventing aggregation in challenging chemical environments, useful for various nanoparticle compositions [21]. |

| Zwitterionic Ligands | Surface coatings that present both positive and negative charges, resulting in a neutral, highly hydrophilic surface [22]. | Can provide superior antifouling properties and a smaller hydrodynamic diameter compared to PEG [22]. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Used to create in vitro models of biological fluid for stability and protein corona studies [21] [1]. | Contains a complex mixture of proteins that simulate the in vivo environment; standard concentration is 10-50% in buffer. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Technique to measure hydrodynamic diameter, size distribution, and stability of nanoparticles in suspension [27] [28]. | Provides an ensemble average; best for monomodal, monodisperse samples. Compliment with microscopy methods. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) | Technique that tracks Brownian motion of individual nanoparticles to determine size distribution and concentration [27] [28]. | Provides high-resolution size distributions and is particularly useful for polydisperse samples and quantifying concentration. |

Surface Engineering Solutions: Coatings and Functionalization Strategies

FAQs: Core Principles and Challenges

What is steric stabilization and why is it crucial for nanoparticles in physiological fluids?

Steric stabilization is the reduction in particle interactions by means of a surface steric barrier, typically created by grafting large molecules like non-ionic polymers or surfactants onto the nanoparticle surface [29]. This barrier provides a repulsive force that prevents nanoparticles from coming into close contact and aggregating. It is crucial for physiological applications because biological fluids have high ionic strengths, which compress the electrical double layer of electrostatically stabilized nanoparticles, causing aggregation. Steric stabilization remains effective under these conditions and can also provide a "stealth" effect, reducing unwanted protein adsorption and rapid clearance by the immune system [1] [29].

How does steric stabilization differ from electrostatic stabilization?

The table below summarizes the key differences:

| Feature | Electrostatic Stabilization | Steric Stabilization |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Repulsion via electrical double layer charge [1]. | Repulsion via a physical polymer barrier [29]. |

| Effectiveness in High Salt | Poor (double layer is compressed) [1]. | Excellent (unaffected by salt) [29]. |

| Sensitivity to pH | High (charge depends on pH). | Low. |

| Freeze-Thaw Stability | Poor. | Good [29]. |

| Primary Polymers | Citrate, charged surfactants. | PEG, PVP, PVA. |

| Quantitative Measurement | Zeta potential [29]. | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), sedimentation, transmittance [29]. |

What are the common failure modes of sterically stabilized nanoparticles in biological applications?

Common failure modes include:

- Protein Corona Formation: Despite steric coatings, proteins in biological fluids can adsorb onto nanoparticles, forming a "corona" that can mask targeting ligands and alter the nanoparticle's biological identity, leading to unintended biodistribution and rapid clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) [1] [30].

- Aggregation in Complex Media: Incomplete coating, low polymer density, or polymer desorption can lead to instability and aggregation in biological fluids [31].

- Immune Recognition: Some polymers, particularly PEG, can elicit immune responses after repeated dosing, leading to accelerated blood clearance (ABC) [32].

- Shear-Induced Degradation: During processing or in circulation, mechanical shear can damage the polymer layer or cause particle aggregation [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Nanoparticle Aggregation in Serum-Containing Media

Symptoms: Increase in hydrodynamic diameter (as measured by DLS), visible precipitation or color change in cell culture media containing serum.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient polymer surface density. | Increase the polymer-to-nanoparticle ratio during coating. Ensure the polymer chains are long enough to provide an effective barrier [29]. |

| Weak anchoring of the stabilizer. | Use polymers with stronger anchoring groups (e.g., thiol-terminated PEG for gold NPs) [1]. |

| Formation of a destabilizing protein corona. | Optimize polymer coverage for better "stealth" properties. Consider using alternative coatings like zwitterionic ligands which exhibit strong antifouling capabilities [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing PEG Coating for Gold Nanoparticles

- Reagents: Citrate-stabilized gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), methoxy-PEG-thiol (mPEG-SH) of various molecular weights (e.g., 2kDa, 5kDa, 10kDa).

- Procedure:

- Purify AuNPs: Concentrate the stock citrate-AuNP solution via centrifugation (e.g., 14,000 rpm for 15 min) and resuspend in deionized water to remove excess citrate.

- PEGylation: Add a calculated excess of mPEG-SH solution to the purified AuNPs under vigorous stirring. The typical final PEG concentration should be in the range of 0.1-1 mM [1].

- Incubate: Allow the reaction to proceed for a minimum of 4 hours at room temperature.

- Purify: Remove unbound PEG by repeated centrifugation and resuspension in the desired buffer (e.g., PBS).

- Validate Stability: Test the stability of the PEGylated AuNPs by adding sodium chloride (e.g., to 0.15 M) and monitoring the UV-Vis spectrum for 1 hour. A stable solution will show no shift or broadening of the surface plasmon resonance peak [1].

Problem 2: Reduced Cellular Uptake After Steric Coating

Symptoms: Nanoparticles show excellent stability and circulation but fail to be internalized by target cells, leading to low therapeutic efficacy.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| The steric barrier is too effective, preventing interactions with the cell membrane. | Use a lower molecular weight PEG or a lower density of PEG to balance stability and uptake [32]. |

| The coating masks active targeting ligands. | Employ a heterofunctional polymer (e.g., SH-PEG-COOH) that allows for conjugation of targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides) at the distal end of the polymer chain, extending beyond the steric layer [1]. |

| The PEG coating triggers the Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC) phenomenon. | Explore alternative non-PEG polymers like PVP or poly(2-oxazoline)s, or use cleavable PEG links that shed upon reaching the target site [32]. |

Problem 3: Inconsistent Batch-to-Batch Stability

Symptoms: Different batches of nanoparticles, synthesized with the same recipe, show varying stability in buffer or physiological fluids.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Variations in mixing efficiency and shear during coating. | Standardize the mixing protocol (speed, time, and vessel geometry). High shear can improve dispersion but may also damage nanoparticles or cause over-heating [33]. |

| Improper purification leaving residual unbound polymer or reactants. | Strictly control the purification steps (e.g., centrifugation speed/duration, number of washes, dialysis time) across all batches. |

| Inconsistent nanoparticle core synthesis leading to variations in size and surface chemistry. | Ensure the synthesis of the core nanoparticles is highly reproducible before beginning the coating process. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Steric Stabilization |

|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | The gold standard. Provides a highly hydrophilic steric barrier, conferring colloidal stability in high salt and stealth properties against protein adsorption [1] [29]. |

| Poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) (PVP) | A non-ionic polymer often used for steric stabilization, especially for metal and oxide nanoparticles. Good solubility in water and various solvents [1]. |

| Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) | A hydrophilic polymer used extensively in the synthesis and stabilization of polymeric nanoparticles (e.g., PLGA). Forms a physical barrier that prevents aggregation. |

| Thiol-terminated Polymers (e.g., PEG-SH) | Provides a strong anchor group for covalent attachment to gold, silver, and other noble metal surfaces, creating a robust steric layer [1]. |

| Carboxyl-terminated Polymers (e.g., PEG-COOH) | Allows for further functionalization of the nanoparticle surface with targeting molecules via carbodiimide chemistry after stabilization [1]. |

| Phospholipid-PEG Conjugates | A key component in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs). The PEG-lipid provides a transient steric shield that prolongs circulation time but can desorb to allow for cellular uptake and endosomal escape [32]. |

Visualizing Steric Stabilization and Experimental Workflow

Steric Stabilization Experimental Workflow

Mechanism of Steric Stabilization

Electrosteric stabilization is a advanced colloidal stabilization mechanism that combines the benefits of electrostatic repulsion and steric hindrance. In the context of physiological fluids research, it is a cornerstone strategy for improving the stability and performance of nanoparticle (NP) systems used in drug development.

Nanoparticles designed for biomedical applications, such as drug delivery or diagnostic imaging, must remain stable in complex biological fluids like blood. These environments are characterized by high ionic strength and a high content of biomacromolecules, notably proteins [34]. A nanoparticle that is stable in pure water can rapidly aggregate under physiological conditions. Aggregation alters key nanoparticle properties, prevents efficient targeting, and can even pose safety risks [34] [35] [3].

Pure electrostatic stabilization, often achieved with small charged molecules like citrate, is ineffective in high-ionic-strength fluids because dissolved salts compress the electrical double layer around the particles, neutralizing their repulsive force and allowing aggregation via van der Waals attraction [34] [3]. Pure steric stabilization, using uncharged polymers like poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), provides a physical barrier that is more effective in high-salt conditions [34]. Electrosteric stabilization synergizes these two approaches by using charged polyelectrolytes—polymers that possess a backbone with charged functional groups. These polymers adsorb onto the nanoparticle surface, providing a robust, combined repulsive force: the long-range electrostatic repulsion from the charges and the short-range, non-compressible steric barrier from the polymer chains [36] [3]. This makes it a powerful strategy for creating nanoparticle dispersions that are stable, functional, and resistant to unwanted protein adsorption in physiological environments.

Key Mechanisms and Research Reagent Solutions

Mechanisms of Action

Electrosteric stabilization operates through two interconnected mechanisms that provide a multi-layered defense against aggregation:

- Electrostatic Repulsion: The charged groups on the polyelectrolyte backbone create an electrical double layer in the surrounding fluid. When two nanoparticles approach, the overlap of their like-charged double layers generates a repulsive force that pushes them apart. This is particularly effective at longer ranges.

- Steric Hindrance: The polymer chains extend from the nanoparticle surface into the solution, creating a physical, "brush-like" barrier. This barrier prevents other nanoparticles from coming close enough for attractive van der Waals forces to dominate. This mechanism is critical for stability in high-ionic-strength environments where electrostatic repulsion is weakened [34] [36] [3].

In biological fluids, an additional challenge is the non-specific adsorption of proteins, forming a "protein corona" that can alter the nanoparticle's biological identity and function [34]. The dense, hydrophilic layer provided by electrosteric stabilizers can impart antifouling properties, reducing protein adsorption and helping the nanoparticle retain its intended function [34].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for implementing electrosteric stabilization in experimental workflows.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Electrosteric Stabilization

| Reagent Category & Examples | Key Function in Electrosteric Stabilization |

|---|---|

| Charged Polyelectrolytes- Poly(acrylic acid) (PAA)- Melamine formaldehyde sulfonate (MFS) | Serves as the primary stabilizer. The charged backbone provides electrostatic repulsion, while the polymer chain itself provides the steric barrier. Adsorbs onto NP surfaces via electrostatic or covalent interactions [36]. |

| Co-stabilizers / Non-ionic Polymers- Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)- Hydroxypropylmethylcellulose (HPMC) | Often used in conjunction with polyelectrolytes to enhance the steric component of the stabilization. PEG is renowned for its "stealth" effect, reducing protein adsorption and opsonization [34] [36]. |

| Surface Coupling Agents- Thiol-terminated PEG (PEG-SH)- Silane coupling agents | Facilitates the covalent anchoring of stabilizers to nanoparticle surfaces. For example, PEG-SH is universally used for grafting onto gold nanoparticles, ensuring a stable, non-desorbing coating [34]. |

| Model Nanoparticles for Method Development- Gold NPs (citrate-stabilized)- Iron oxide NPs- TiO2 NPs | Used as benchmark systems to test and optimize electrosteric stabilization protocols due to their well-understood surface chemistry and availability [34] [37] [3]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

This section provides a detailed methodology for preparing and characterizing electrosterically stabilized nanoparticles.

Protocol: Preparing Electrosterically Stabilized Gold Nanoparticles

This protocol outlines a common ligand exchange process to replace citrate stabilizers on pre-synthesized gold nanoparticles with a charged polyelectrolyte or a mixed polymer system.

Materials:

- Citrate-stabilized gold nanoparticles (e.g., 15 nm diameter)

- Thiol-terminated methoxy-PEG (mPEG-SH, e.g., MW 5000 Da)

- Charged polyelectrolyte solution (e.g., Poly(acrylic acid), PAA)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, 1X, pH 7.4) or other high-ionic-strength buffer for stability testing

- Ultrapure water

- Benchtop centrifuge and centrifugal filter units (e.g., 100 kDa MWCO)

Procedure:

- Characterization of Starting Material: Characterize the initial citrate-stabilized NP solution by measuring its UV-Vis absorption spectrum, hydrodynamic diameter, and zeta potential using dynamic light scattering (DLS).

- Ligand Exchange: a. Add a calculated excess of mPEG-SH and PAA directly to the stirred NP solution. The typical final PEG concentration is micromolar to millimolar, tailored to achieve a target grafting density [34]. b. Allow the reaction to proceed for a minimum of 2-4 hours at room temperature with continuous stirring to ensure complete ligand exchange.

- Purification: a. Purify the coated nanoparticles from unbound ligands via centrifugation (if NPs are large enough) or using centrifugal filter units with an appropriate molecular weight cutoff (e.g., 100 kDa). b. Re-disperse the pellet or retentate in ultrapure water. Repeat this wash cycle 2-3 times.

- Final Characterization: a. Re-measure the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of the purified NPs in water. A successful coating will typically result in a small increase in diameter and a shift in zeta potential towards the value of the new polymer coating. b. Proceed to stability testing.

Stability Testing in Physiological Conditions

The efficacy of the electrosteric coating must be validated under biologically relevant conditions.

Procedure:

- Salt Stability Test: Incubate the stabilized NP dispersion with an equal volume of 2X PBS (final concentration: 0.15 M NaCl). Monitor the solution for visible aggregation (color change from red to blue/black for gold NPs) over 1-2 hours. Use UV-Vis spectroscopy to track changes in the surface plasmon resonance peak over time [34].

- Quantitative Stability Assessment: Use DLS to measure the hydrodynamic diameter of the NPs in PBS over time (e.g., at 0, 1, 4, and 24 hours). A stable formulation will show no significant increase in size.

- Protein Corona Challenge: Incubate the NPs with a biologically relevant medium such as fetal bovine serum (FBS) or a solution of bovine serum albumin (BSA) for a set period (e.g., 1 hour). Purify the NPs and measure their diameter and zeta potential to assess the degree of protein adsorption [34].

The entire workflow, from synthesis to validation, can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for preparing and validating electrosterically stabilized nanoparticles.

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs

This section addresses common experimental problems and their solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Aggregation during ligand exchange | Rapid, uncontrolled displacement of original stabilizer. | Add the new polymer stabilizer solution dropwise to the vigorously stirred NP solution. Use a slight molar excess, not a vast overdose. |

| Instability in high salt (PBS) | Insufficient polymer grafting density; weak electrostatic component. | Increase polymer concentration during coating. Ensure the polymer charge is opposite to the NP's initial surface charge for stronger adsorption. Consider using a higher MW polymer. |

| Increased hydrodynamic size after serum incubation | Significant protein corona formation due to inadequate antifouling properties. | Optimize the density and length of PEG chains in your coating. Consider using zwitterionic polymers, which are highly resistant to protein adsorption [34]. |

| Poor Colloidal Stability in Complex Media | Compressed electrostatic layer and insufficient steric barrier. | Implement a combined "electrosteric" stabilizer like a graft copolymer with a charged backbone and neutral (e.g., PEG) side chains, which provides both repulsive mechanisms simultaneously [36]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is purely electrostatic stabilization insufficient for nanoparticles in physiological fluids? Biological fluids like blood have a high ionic strength. These ions compress the electrical double layer around a charged nanoparticle, effectively shielding the charges and eliminating the repulsive force that prevents aggregation. Van der Waals attraction then dominates, leading to rapid particle aggregation and precipitation [34] [3].

Q2: How do I choose the right molecular weight for a PEG-based stabilizer? The choice involves a trade-off. Lower molecular weight (MW) PEGs (e.g., 2k Da) allow for a higher grafting density (more polymer chains per nm²), which can create a denser brush. Higher MW PEGs (e.g., 10k Da) provide a thicker steric barrier but at a lower grafting density. Research indicates that for 15 nm gold NPs, the number of PEG chains per nanoparticle decreases from ~695 for PEG2000 to ~50 for PEG51400, but the overall steric cloud is more effective at preventing protein adsorption [34].

Q3: What analytical techniques are critical for characterizing electrosteric stabilization?

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Measures hydrodynamic diameter and monitors size increase (aggregation) over time.

- Zeta Potential Measurement: Determines the surface charge, indicating successful adsorption of a charged polyelectrolyte.

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Useful for certain NPs (e.g., gold); a shift or broadening of the absorption peak indicates aggregation.

- Techniques like XPS or FTIR: Can confirm the chemical presence of the polymer stabilizer on the NP surface.

Q4: Our nanoparticles are stable in water but aggregate in cell culture media. What is the primary cause? Cell culture media is a high-ionic-strength environment often containing divalent cations (like Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺) and proteins. Divalent cations are particularly effective at neutralizing negative surface charges and can even bridge between particles. This, combined with the general shielding effect of ions, collapses electrostatic stabilization. Your steric component is likely insufficient. Consider increasing the polymer coating density or using a stabilizer with a stronger combined electrosteric effect [34] [3].

Stealth and Antifouling Strategies to Minimize Protein Adsorption

When nanoparticles (NPs) enter a physiological fluid (e.g., blood), they are immediately surrounded by a complex mixture of proteins. These proteins can rapidly adsorb onto the NP surface, forming a layer known as the "protein corona" [38] [39]. This corona masks targeting ligands, triggers recognition by immune cells, and leads to rapid clearance from the bloodstream, ultimately compromising the therapeutic efficacy of the nanomaterial [34] [40]. Stealth and antifouling strategies are therefore essential to design NPs that can evade this protein adsorption, remain stable in biological environments, and successfully reach their intended target.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Q1: My nanoparticles are aggregating in serum. What are the primary stabilization methods I should consider?

A: Colloidal stability in high-ionic-strength environments like serum is fundamental. The two primary stabilization methods are:

- Electrostatic Stabilization: Relies on surface charge (e.g., citrate-stabilized NPs) to create repulsion between particles. This method often fails in biological fluids because high salt concentrations compress and neutralize the electrical double layer, leading to aggregation [34].

- Steric Stabilization: Creates a physical barrier on the NP surface using hydrophilic polymers. This is the recommended approach for physiological conditions. The polymer layer prevents particles from coming into close contact, thereby overcoming van der Waals attraction forces [34].

Q2: I am using PEG, but my nanoparticles are still being opsonized. What could be going wrong?

A: The efficacy of PEG is highly dependent on its surface presentation. The most common issues are:

- Low Grafting Density: If PEG chains are too sparse on the NP surface, proteins and opsonins can penetrate the polymer layer and interact with the underlying material [38] [40].

- Insufficient Molecular Weight: Shorter PEG chains may not form a thick enough hydration layer to provide effective steric repulsion. Higher molecular weight PEG provides a larger exclusion volume [34].

- Instability of the Surface Anchor: For metallic NPs, using a thiol-terminated PEG (PEG-SH) provides a strong covalent anchor. Ensure the ligand exchange process from initial stabilizers (e.g., citrate) is complete and stable [34].

Q3: Are there alternatives to PEG for antifouling surfaces?

A: Yes, research has identified several promising alternatives to PEG, which can sometimes elicit immune responses after repeated dosing.

- Poly(Zwitterions): Polymers like poly(carboxybetaine) (pCB) and poly(sulfobetaine) (pSB) are highly hydrophilic and form a strong hydration layer via electrostatic interactions, providing excellent antifouling properties [38] [40].

- Poly(2-Oxazoline)s (POx): This class of polymers is considered a potential PEG substitute due to its high hydrophilicity, stability, and potential for reduced immunogenicity [40].

- Biomimetic Coatings: These include "self" markers like the CD47 protein, which signals "don't eat me" to immune cells, or lipid bilayers that mimic natural cell membranes [40].

Q4: How can I experimentally determine if my stealth coating is working?

A: You can use several techniques to characterize protein adsorption and colloidal stability:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Measure the hydrodynamic diameter of your NPs before and after incubation with serum or plasma. A significant increase in size indicates protein adsorption and corona formation [38].

- Zeta Potential Measurement: The surface charge of NPs will often shift towards the charge profile of the adsorbed proteins (typically negative for most plasma proteins) [38].

- Gel Electrophoresis: After incubating NPs with serum, you can separate the particles from unbound proteins and analyze the hard corona proteins bound to the NP surface [38].

- Mass Spectrometry: This is used to identify the specific protein composition of the corona, providing deep insight into the biological identity the NP will present in vivo [38].

Comparison of Stealth Polymers and Their Properties

Table 1: Key characteristics of common polymers used for stealth coating of nanoparticles.

| Polymer | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantages | Key Challenges / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(Ethylene Glycol) (PEG) [34] [40] | Steric hindrance & formation of a hydrated layer | "Gold standard"; well-established chemistry; proven to reduce opsonization and prolong circulation | Potential for anti-PEG antibodies; grafting density and molecular weight are critical for performance |

| Poly(Zwitterions) [38] [40] | Formation of a super-hydrophilic layer via strong electrostatic hydration | Excellent antifouling; often outperforms PEG; highly biocompatible | Synthesis and conjugation can be more complex than for PEG |

| Poly(2-Oxazoline) (POx) [40] | Steric stabilization, similar to PEG | High versatility and stability; potential alternative for PEG-sensitive applications | Considered a emerging polymer; long-term toxicity profile less established than PEG |

| Biomimetic (CD47) [40] | Engagement of "don't eat me" signaling pathways with immune cells | Highly specific biological mechanism; can directly inhibit phagocytosis | Complexity of production and conjugation; cost |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: PEGylation of Citrate-Stabilized Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) via Ligand Exchange

This protocol describes a common method for conferring steric stability to metallic NPs using thiol-terminated PEG (PEG-SH) [34].

1. Materials:

- Citrate-stabilized AuNPs (e.g., 15 nm diameter)

- Methoxy-PEG-Thiol (mPEG-SH, e.g., MW 5000 Da)

- Deionized water

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Ultrafiltration centrifugal devices (e.g., 100 kDa MWCO)

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Add a calculated excess of mPEG-SH solution directly to the stirred citrate-stabilized AuNP colloid. The target is a high surface density (for 15nm AuNPs and PEG5000, aim for ~3.9 PEG molecules per nm²) [34].

- Step 2: Allow the reaction to proceed with continuous stirring for at least 4-6 hours at room temperature. The thiol groups will covalently bind to the gold surface, displacing the citrate ions.

- Step 3: Purify the pegylated AuNPs from unbound PEG and citrate by repeated centrifugation and washing with PBS using ultrafiltration devices. This step is critical to remove all unbound ligands.

- Step 4: Re-suspend the final PEGylated NP pellet in PBS or another desired buffer. The NPs are now ready for stability testing.

3. Validation of PEGylation:

- Stability Test: Add an equal volume of 1 M NaCl to a sample of your PEGylated NPs and a sample of the original citrate NPs. The citrate NPs will aggregate (visible by a color change from red to blue), while the PEGylated NPs should remain stable [34].

- DLS/Zeta Potential: Measure the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential. Successful PEGylation will typically result in a slight increase in diameter and a shift of the zeta potential towards neutral [34].

Protocol 2: Stability and Protein Adsorption Assay in Physiological Fluids

This protocol outlines how to test the stability and antifouling performance of your stealth-coated NPs in a biologically relevant medium [38].

1. Materials:

- Stealth-coated NPs and control NPs (e.g., citrate-stabilized or bare NPs)

- Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) or human plasma

- Incubation buffer (e.g., PBS)

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) / Zetasizer instrument

- Benchtop centrifuge

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Incubate your NPs in a high-concentration serum solution (e.g., 50-90% FBS in PBS) at 37°C for a predetermined time (e.g., 1 hour).

- Step 2: Purify the NP-protein complexes from unbound proteins. This can be done by gentle centrifugation or size-exclusion chromatography to avoid disrupting the "hard corona" [38].

- Step 3: Re-suspend the pellet in a clean buffer.

- Step 4: Characterize the NPs.

- Use DLS to measure the increase in hydrodynamic diameter, which indicates the thickness of the protein corona.

- Use gel electrophoresis to separate and visualize the proteins bound to the NPs.

3. Troubleshooting:

- Problem: Large aggregates form immediately upon adding serum.

- Solution: The colloidal stability of the NPs in high ionic strength is insufficient. Optimize your steric coating (e.g., increase PEG density or molecular weight) [34].

- Problem: Significant protein adsorption is still measured on stealth-coated NPs.

- Solution: The antifouling coating is not dense or effective enough. Consider switching to a more potent polymer like zwitterions or increasing the grafting density of your current polymer [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and their functions in developing stealth nanoparticles.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| PEG-SH (Thiol-terminated PEG) [34] | Covalent attachment to gold, silver, and quantum dot surfaces. Provides steric stabilization. | Molecular weight (1k-40k Da) impacts coating density and stealth efficacy. |

| Lipids (DSPC, Cholesterol, PEG-lipids) [41] [42] | Core components of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and liposomes. PEG-lipids confer stealth. | Molar ratio of PEG-lipid is critical; too much can hinder cellular uptake. |

| Trehalose / Sucrose [42] | Cryoprotectants and lyoprotectants for long-term storage of nanoparticles. Prevent aggregation during freezing or lyophilization. | Typically used at 5-10% (w/v) concentration. Essential for maintaining stability in aqueous formulations. |

| Zwitterionic Lipids or Polymers [38] [40] | Create a super-hydrophilic surface that strongly binds water molecules, resisting protein adsorption. | Examples include phospholipids like DSPC and polymers like poly(carboxybetaine). |

| CD47-derived Peptides [40] | Functionalization to signal "self" to macrophages, actively inhibiting phagocytosis. | A biomimetic alternative to polymer-based stealth; often used in combination with other strategies. |

Conceptual Workflows and Relationships

Stealth NP Development Pathway

Protein Corona Formation Process

Ligand Exchange and Covalent Grafting for Robust Surface Attachment

For researchers in nanomedicine and drug development, achieving stable nanoparticle dispersions in physiological fluids is a fundamental hurdle. Biological fluids, characterized by high ionic strengths and abundant proteins, often cause uncontrolled nanoparticle aggregation or lead to the formation of a protein corona. This corona can mask targeting ligands and cause rapid clearance from the bloodstream, thereby compromising both the diagnostic and therapeutic efficacy of the nanomaterial [1] [34]. Surface engineering through ligand exchange and covalent grafting is a critical strategy to overcome these challenges, forming the cornerstone of robust and translatable nanobiotechnology.

This technical support center is designed to address the specific, practical issues you might encounter during your experiments, providing troubleshooting guides and detailed protocols to improve the success rate of your surface functionalization strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why does my nanoparticle solution aggregate immediately upon addition to cell culture media or simulated body fluid?

This is a classic sign of insufficient colloidal stabilization. Cell culture media and physiological buffers have high ionic strength, which compresses the electrical double layer around electrostatically stabilized nanoparticles (e.g., citrate-coated gold nanoparticles). This compression neutralizes the repulsive forces between particles, allowing attractive van der Waals forces to dominate and cause aggregation [1] [34]. Switching from electrostatic stabilization to steric stabilization using covalently grafted polymers like PEG is the standard solution.

2. My functionalized nanoparticles lose their targeting capability in biological environments. What could be the cause?

The most likely culprit is the non-specific adsorption of proteins, forming a "protein corona" around the nanoparticle. This corona can physically block the targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides) attached to your nanoparticle surface, effectively hiding them from the intended receptors on cells [1] [30]. Implementing an effective antifouling strategy, such as creating a dense PEG brush layer, can shield the surface and help preserve targeting specificity [34] [43].

3. After ligand exchange, my nanoparticles precipitate. How can I prevent this?

Precipitation during ligand exchange often occurs due to an abrupt loss of colloidal stability during the transition from old to new ligands. To mitigate this:

- Gradual Addition: Add the new ligand solution to the nanoparticle dispersion slowly and with vigorous stirring.

- Purification: Purify the nanoparticles to remove excess original surfactants that might compete with the new ligands.

- pH Control: Ensure the pH of the solution is optimized for the binding of your new ligand. For example, using thiolated PEG for gold nanoparticles is typically done at a neutral or slightly basic pH [1] [44].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Incomplete Ligand Exchange on Noble Metal Nanoparticles (Au, Ag)

Problem: After a standard ligand exchange procedure with a thiolated PEG, subsequent characterization (e.g., FTIR, NMR) shows significant residual original ligands (e.g., citrate, CTAB) on the nanoparticle surface, leading to poor stability.

Investigation & Resolution:

| Observation | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low grafting density of new ligand | Insufficient concentration of incoming ligand | Increase the molar excess of the new ligand (e.g., thiolated PEG) relative to the estimated surface sites [1]. |